Abstract

Background/Aims

Probiotics appear to improve Helicobacter pylori-associated dyspepsia via an inhibitory effect on H. pylori; however, uncertainty exists regarding their effects in H. pylori-uninfected individuals. We evaluated the efficacy of Lactobacillus gasseri OLL2716 (L. gasseri OLL2716) on H. pylori-uninfected individuals with functional dyspepsia (FD).

Methods

A double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, randomized, controlled trial was performed. Participants were randomly assigned to ingest L. gasseri OLL2716-containing yogurt (L. gasseri OLL2716 group) or L. gasseri OLL2716-free yogurt (placebo group) for 12 weeks. Participants completed questionnaires that dealt with a global assessment as well as symptom severity. The per-protocol (PP) population was evaluated for efficacy in accordance with a plan prepared beforehand.

Results

Randomization was performed on 116 individuals; the PP population consisted of 106 individuals (mean age 42.8 ± 9.0). The impressions regarding the overall effect on gastric symptoms were more positive in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group compared to that in the placebo group (statistical trend; p = 0.073). The elimination rate for major FD symptoms was 17.3 and 35.3% in the placebo and L. gasseri OLL2716 groups respectively (p = 0.048).

Conclusion

L. gasseri OLL2716 has beneficial effects on FD without H. pylori involvement.

Keywords: Probiotics, Epigastric, Postprandial distress syndrome, Functional gastrointestinal disorder, Rome III classification

Introduction

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a condition with persistent abdominal symptoms affecting mainly the epigastrium. It is believed to originate from the stomach and duodenum despite the absence of an organic, systemic, or metabolic disease that could explain the symptoms. Two FD subtypes have been defined: postprandial distress syndrome (PDS), which is characterized by postprandial fullness and early satiety, and epigastric pain syndrome (EPS), which is characterized by epigastric pain and epigastric burning [1]. FD is diagnosed based on a certain number of subjective symptoms due to the absence of widely applicable biomarkers [2]. No treatment allowing for a complete cure has yet been fully established, and in many cases, symptoms disappear and recur repeatedly in the long term, causing a marked deterioration in the quality of life [3].

The etiopathology of FD remains unclear. However, the condition often overlaps with disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and gastroesophageal reflux disease; the etiopathologies of these conditions are believed to have commonalities. Stress is known to be involved in these conditions, and findings in research studies on brain-gut interactions, which involve the central nervous system, have suggested that various symptoms might be due to motor function abnormalities and visceral hypersensitivity mediated by brain-gut interactions [4, 5]. In addition, Helicobacter pylori-associated FD [6] and post-infectious FD [7] have been reported, and an association between FD and abnormalities of gastrointestinal mucosal immunity has attracted attention.

Probiotics are lactic acid bacteria that are beneficial for health and they have been reported to be effective in the treatment of IBS [8, 9]. However, it does not necessarily follow that probiotics improve FD as well as IBS. The ameliorating effect of probiotics on IBS is believed to result in improved mucosal permeability by reducing abnormalities of the intestinal microbiota [9, 10, 11]. Meanwhile, the duodenum, a site of few bacteria, has recently been a focus of attention as an organ involved in the onset of FD [12, 13]. Thus, probiotics could improve H. pylori-associated dyspepsia through an inhibitory effect on H. pylori; however, it remains unclear whether probiotics can improve FD symptoms in H. pylori-uninfected individuals. Meta-analyses have shown the effectiveness of H. pylori eradication therapy to be low, with the number of patients required to achieve improvement in one person (the number needed to treat) to be 14 [14]. This suggests that H. pylori infection is just one of the factors causing FD symptoms, and we believe it is important to clinically evaluate whether probiotics are effective against H. pylori-uninfected FD individuals. In addition, only a few reports have suggested thus far that probiotics might be effective for FD [15, 16, 17, 18]. Therefore, we performed a double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, randomized, controlled trial (RCT) with L. gasseri OLL2716 in H. pylori-uninfected FD individuals.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

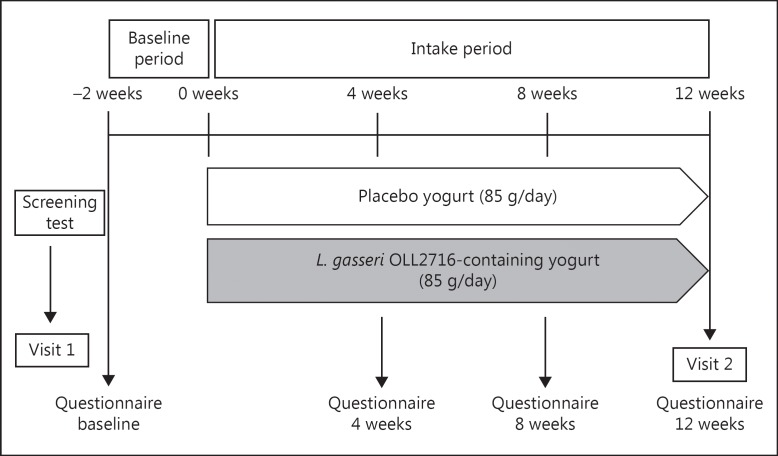

A double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled RCT was performed, with participants assigned to one of 2 groups: the L. gasseri OLL2716 group or the placebo group (Fig. 1). The study was performed between July 22, 2014 and December 1, 2014, at the Sekino Clinical Pharmacology Clinic (Tokyo, Japan). Approval for the study was obtained following a review of its ethical and scientific validity by the Ethics Committee of Meiji Co., Ltd., as well as by the Ethics Committee of HUMA R&D Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). In compliance with ethical principles based on the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical guidelines for epidemiological research, the purpose and contents of this study were fully explained to the participants before participation, and written informed consents were obtained from all the participants.

Fig. 1.

Trial design and schedule.

Participants

Japanese individuals, between the ages of 20 and 64 years, with complaints involving the epigastric region and who had not received any treatment were recruited. At the screening test (visit 1), recruited individuals were confirmed to have had 1 or more of the 4 symptoms of dyspepsia defined according to Rome III criteria (bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiety, epigastric pain, and epigastric burning) during the preceding 6-month period (or more), with such symptoms occurring regularly during the last 3-month period [1]. In addition, recruited individuals were confirmed to be H. pylori-negative. Individuals who met the selection criteria and did not meet any of the exclusion criteria were considered eligible. The exclusion criteria were as follows: consultation with medical institutions during the 6-month period prior to the study for diabetes or disorders of the gastrointestinal tract; medical treatment for dyspepsia symptoms during the 6-month period preceding the study; oral treatments using low-dose aspirin, as well as regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents during the 6-month period preceding the study; suspected diabetes, gastrointestinal disorders, or severe renal impairment on the basis of blood tests (hematology and biochemistry), medical examination by interview, and physical examination at the time of the screening; moderate or severe heartburn or reflux symptoms during the 3-month period preceding the study; history of receiving H. pylori eradication therapy; ingestion of lactic acid bacteria-containing food products 3 times or more per week during the 3-month period preceding the screening tests.

This trial was conducted without an endoscopy; however, we confirmed the absence of organic disease, which could be related to dyspepsia symptoms, by confirming the participants to be H. pylori-uninfected, and by excluding the participants with alarming symptoms as well as those who had received medical treatment at risk for organic gastrointestinal disease. In Japan, it was reported that only 9% of patients with dyspepsia symptoms had organic disease by the endoscopy examination [19]. Since healthy participants were screened among the general population who had not received medical treatment for the dyspepsia symptoms, we did not perform endoscopy on them considering the participant's burden.

H. pylori Screening

Serum anti-H. pylori antibody titers were measured using the sandwich ELISA method (E plate; Eiken), and serum pepsinogen levels (serum PG) were measured using the latex agglutination test (L-Z test; Eiken). It was reported that the sensitivity and specificity of serum PG levels for detecting H. pylori-positive subjects were both over 90% among Japanese, using PG II ≥12 and PG I/II ratio ≤4.5 for the cutoff value [20]. Thus, individuals who met the following 2 conditions at the same time were considered H. pylori-negative: PG II <12 with a PG I/II ratio ≥4.5, and serum anti-H. pylori antibody levels <3 U/mL.

Study Protocol

For individuals considered to be eligible for the study at the time of the screening, confirmation was obtained once again during the baseline period, ensuring that the selection criterion regarding the 4 symptoms of dyspepsia was satisfied. A third-party institution (Nihonbashi Egawa Clinic, Tokyo, Japan) then assigned the pooled subjects collectively and randomly into two groups. Stratified randomization was performed to balance the gender and the FD subtype across the 2 groups. In the placebo group, participants were instructed to ingest one unit (85 g) of yogurt made from a mixture of raw milk, dairy products, sugar, a sweetener (stevia), and raw water, fermented with Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococus thermophiles. In the L. gasseri OLL2716 group, participants were instructed to ingest L. gasseri OLL2716-containing yogurt that was made by addition of L. gasseri OLL2716 to the same type of yogurt as above (amount of L. gasseri OLL2716 per unit of yogurt: 109 CFU or higher). The nutrients per unit (85 g) of placebo and L. gasseri OLL2716-containing yogurt were as follows: energy, 68 kcal; protein, 2.9 g; lipids, 2.6 g; carbohydrates, 8.3 g; sodium, 37 mg; and calcium, 102 mg. Verifications were performed to confirm that the test food products were indistinguishable based on their flavor and external appearance, and participants were instructed to ingest one unit (85 g) of the assigned test food product per day for 12 weeks. No restriction was imposed regarding the time of intake.

Assessments

Global Assessment

As a global participant assessment, a questionnaire determining the participant's impression of the overall effect of the 12-week intake of the test food product on gastric symptoms was completed. The participants were instructed to answer the question, “How have your overall gastric symptoms been during the past week, compared with your symptoms during the baseline period preceding the intake of the food product?,” on a 7-point Likert scale as follows [21, 22]: (1) extremely improved compared with the baseline period; (2) improved compared with the baseline period; (3) slightly improved compared with the baseline period; (4) no change; (5) slightly aggravated compared with the baseline period; (6) aggravated compared with the baseline period; and (7) extremely aggravated compared with the baseline period.

Individual Symptom Scores

A questionnaire regarding the severity of individual FD symptoms and accompanying symptoms was completed during the baseline period and after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of test food intake. Participants rated the severity of symptoms (heartburn, epigastric pain, epigastric burning, postprandial fullness, epigastric bloating, early satiety, belching, nausea, abdominal bloating, and reflex feeling of gastric acid) occurring in the prior week on a 7-point Likert scale as follows [23, 24]: (1) none (absence of symptoms); (2) extremely mild (symptoms could be entirely ignored); (3) mild (symptoms easily tolerated); (4) moderate (symptoms noticed by the patient, but did not affect daily activities); (5) moderate-to-severe (symptoms occasionally limited daily activities); (6) severe (symptoms often limited daily activities); and (7) extremely severe (considerable interference with daily activities, often requiring rest).

Symptom Elimination Rates

The disappearance of a dyspepsia symptom was defined as the absence of an individual FD symptom based on the Likert scales mentioned above. The elimination rate for the 4 major FD symptoms [24] was calculated for each group using the following formula: the number of participants who experienced the disappearance of symptoms / the number of participants in the group × 100. The elimination rate for PDS symptoms was calculated for each group using the following formula: the number of participants classified as PDS (during the baseline period) who experienced the simultaneous disappearance of postprandial fullness and early satiety / the number of participants classified as PDS (during the baseline period) in the group × 100. The elimination rate for EPS-like symptoms was similarly calculated for each group.

Endpoints

Primary endpoint: the primary endpoint was the global assessment (the participant's impression regarding the overall effect of the 12-week test food intake on gastric symptoms).

Secondary endpoints: (1) the elimination rate for the 4 major symptoms of FD was assessed during the baseline period and after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of test food intake. In addition, the elimination rate for each FD subtype (PDS, EPS) symptom was assessed by performing a stratified analysis. (2) The individual FD symptom scores and those of the accompanying symptoms were assessed during the baseline period and after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of test food intake.

Safety Assessmen

Adverse events and side effects occurring during the study period were assessed in both groups for participants who had ingested the test food product at least once.

Statistical Analysis

We previously reported that yogurt containing L. gasseri OLL2716 significantly suppressed the postprandial fullness in H. pylori-infected subjects when compared to the condition between the baseline period and after 12 weeks of test food intake. However, the placebo yogurt did not significantly suppress postprandial fullness [15]. Based on the data from previous studies on L. gasseri OLL2716, the sample size was estimated by an analysis of covariance. Thus, a sample size of 108 was estimated to be sufficient to detect (detection rate, 80%) a potential ameliorating effect on postprandial fullness in comparison to the placebo group, with the significance level set to less than 5%.

Group comparisons at baseline were performed using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and unpaired Student t or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. Statistical analyses of the primary endpoint and individual symptom scores were performed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Statistical analyses of the symptom elimination rate were performed using Fisher's exact tests. The significance level was set to 5% on both sides. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistics 19 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). In accordance with a study execution plan prepared beforehand, an analysis of effectiveness was performed against the per-protocol (PP) population.

Results

Participant Selection and Characteristics

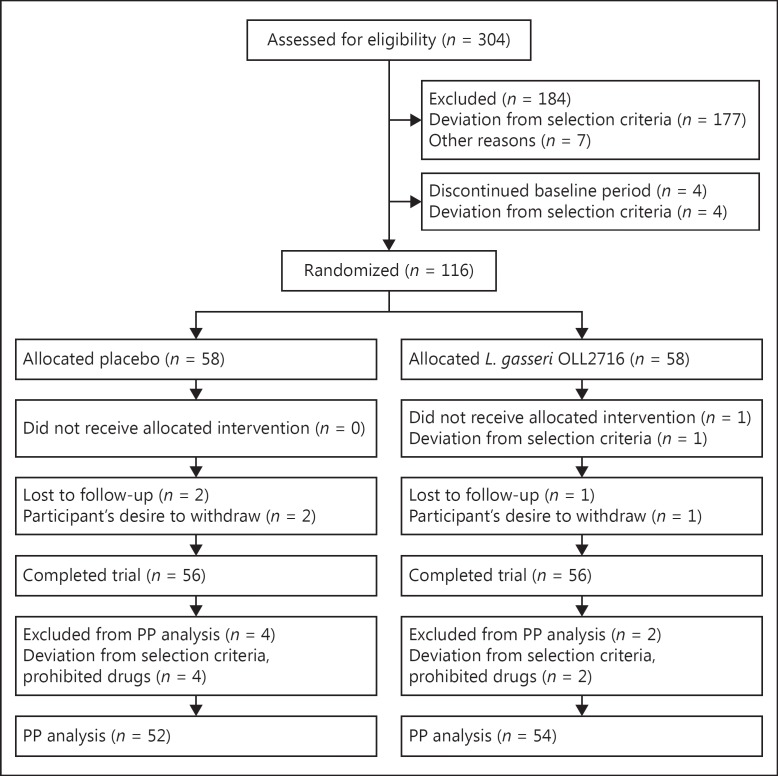

Screening tests were performed in 304 Japanese individuals between the ages of 20 and 64 years who had epigastric complaints and had not received any treatment (Fig. 2). Randomization was performed on 116 individuals (58 individuals in each group), and 112 participants completed the study. However, 6 of those who completed the study were found to have taken prohibited oral medications (antibiotics). Therefore, the PP population consisted of 106 individuals (L. gasseri OLL2716 group, 54 individuals; placebo group, 52 individuals). Among the PP population (27 male, 79 female; mean age 42.8 ± 9.0 years), a total of 81 individuals were classified as PDS, while none of the participants met all the Rome III criteria defining EPS; thus, EPS-like dyspepsia accounted for 38 individuals. In the baseline characteristics of participants in the PP population, no significant group differences were found (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Trial flow. PP, per-protocol.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants in the PP population

| Characteristics | PP total | Group |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| placebo (n = 52) | L. gasseri OLL2716 (n = 54) | |||

| Age, years, mean ± SD† | 42.8±9.0 | 43.1±8.9 | 42.4±9.1 | 0.687 |

| Gender, n (%)§ | 1.000 | |||

| Female | 79 (74.5) | 39 (75.0) | 40 (74.0) | |

| Male | 27 (25.5) | 13 (25.0) | 14 (25.9) | |

| Height, cm, mean ± SD† | 162.5±8.2 | 162.4±8.8 | 162.6±7.6 | 0.913 |

| Weight, kg, mean ± SD† | 53.8±10.2 | 53.4±9.2 | 54.2±11.1 | 0.693 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD† | 20.3±2.7 | 20.2±2.6 | 20.3±2.9 | 0.765 |

| FD subtype, n (%)§ | 0.933 | |||

| PDS alone | 68 (64.2) | 33 (63.5) | 35 (64.8) | |

| EPS-like alone | 13 (l2.3) | 7 (13.5) | 6 (11.1) | |

| Overlap with PDS and EPS-like | 25 (23.6) | 12 (23.1) | 13 (24.1) | |

| Individual FD symptoms scores, median (25–75 percentile)‡ | ||||

| Postprandial fullness | 3.00 (3.00–4.00) | 3.00 (3.00–4.00) | 4.00 (3.00–4.00) | 0.764 |

| Early satiety | 4.00 (3.00–4.00) | 4.00 (2.25–4.00) | 4.00 (3.00–4.00) | 0.968 |

| Epigastric pain | 2.00 (l.00–3.00) | 2.00 (1.25–3.75) | 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 0.601 |

| Epigastric burning | 1.00 (1.00–2.00) | 1.00 (1.00–2.00) | 1.50 (1.00–2.00) | 0.900 |

| Reported gastrointestinal symptoms including minor symptoms, n (%)§ | ||||

| Postprandial fullness | 102 (96.2) | 50 (96.2) | 52 (96.3) | 1.000 |

| Early satiety | 100 (94.3) | 49 (94.2) | 51 (94.4) | 1.000 |

| Epigastric pain | 78 (73.6) | 39 (75.0) | 39 (72.2) | 0.827 |

| Epigastric burning | 51 (48.1) | 24 (46.2) | 27 (50.0) | 0.703 |

| Epigastric bloating | 92 (86.8) | 47 (90.4) | 45 (83.3) | 0.392 |

| Nausea | 33 (31.1) | 16 (30.8) | 17 (31.5) | 1.000 |

| Belching | 71 (67.0) | 36 (69.2) | 35 (64.8) | 0.683 |

| Heartburn | 55 (51.9) | 28 (53.8) | 27 (50.0) | 0.703 |

| Reflex feeling of gastric acid | 36 (34.0) | 19 (36.5) | 17 (31.5) | 0.683 |

| Abdominal bloating | 89 (84.0) | 45 (86.5) | 44 (81.5) | 0.599 |

| Occupation, n (%)§ | 0.661 | |||

| Company employee | 46 (43.4) | 22 (42.3) | 24 (44.4) | |

| Self-employed business | 6 (5.7) | 2 (3.8) | 4 (7.4) | |

| Part-time job | 19 (17.9) | 8 (15.4) | 11 (20.4) | |

| Student | 5 (4.7) | 3 (5.8) | 2 (3.7) | |

| Full-time homemaker | 29 (27.4) | 17 (32.7) | 12 (22.2) | |

| Unemployed | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | |

PP, per-protocol; PDS, postprandial distress syndrome; EPS, epigastric pain syndrome.

Group comparison:

unpaired Student t test

Wilcoxon rank sum test

Fisher's exact test.

Primary Endpoint

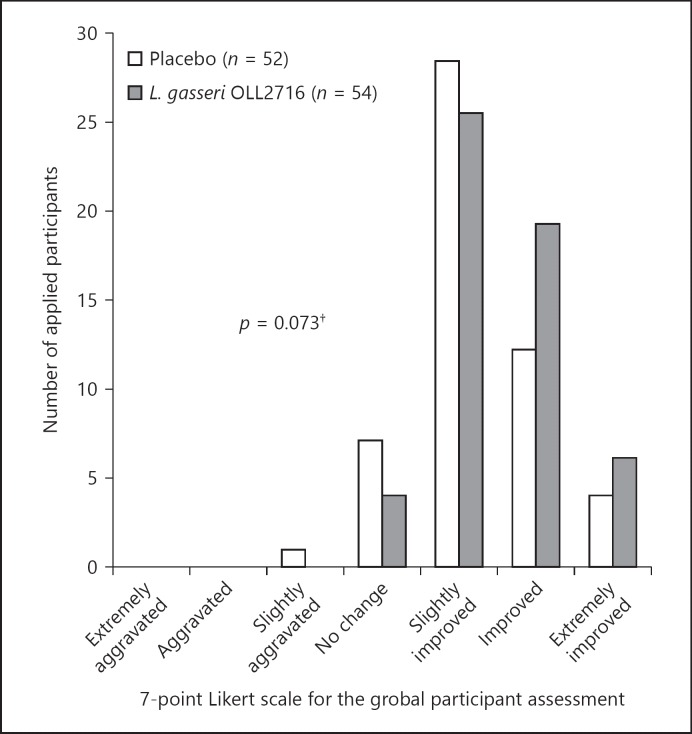

Although the participant's impression regarding the overall effects of the 12-week test food intake on the gastric symptoms was more positive in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group compared to that in the placebo group, the difference reached a statistical trend and was not significant (p = 0.073; Fig. 3). The percentages of individuals who responded that symptoms were “very much aggravated,” “aggravated,” “slightly aggravated,” “unchanged,” “slightly improved,” “improved,” or “very much improved” after the 12-week test food intake were 0, 0, 1.9, 13.5, 53.8, 23.1, and 7.7%, respectively, in the placebo group; and were 0, 0, 0, 7.4, 46.3, 35.2, and 11.1%, respectively, in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group.

Fig. 3.

Global assessment for the treatment effect on gastric symptoms (per-protocol). The participants were instructed to answer the following question after 12 weeks of test food intake: “How have your overall gastric symptoms been during the past week, compared with your symptoms during the baseline period preceding the intake of the food product?” Group comparison; Wilcoxon rank sum test, †p < 0.10 (2-sided).

Secondary Endpoints

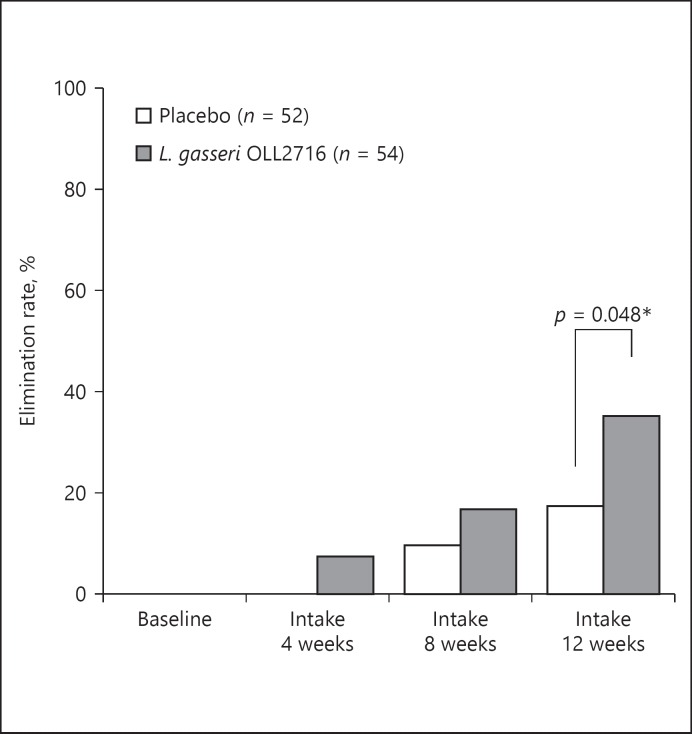

Symptom Elimination Rates

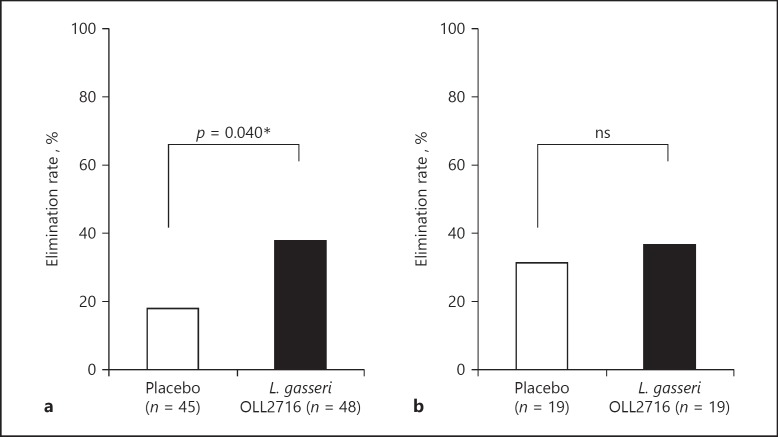

As shown in Figure 4, the elimination rate for the 4 major FD symptoms after the 12-week test food intake was 17.3% in the placebo group and 35.2% in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group, with a statistically significant group difference (p = 0.048). In addition, as shown in Figure 5, the elimination rate for PDS symptoms after the 12-week test food intake was 17.8% in the placebo group and 37.5% in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group, with a statistically significant group difference (p = 0.040). However, the elimination rate for EPS-like symptoms was 31.6% in the placebo group and 36.8% in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group, with no statistically significant difference (p = 1.000).

Fig. 4.

The elimination rate for the 4 major FD symptoms across time (per-protocol). A questionnaire survey on the severity of individual FD symptoms was completed during the baseline period and after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of test food intake. The percentage of the participants who experienced the disappearance of the 4 major FD symptoms was measured as the elimination rate at each time point. Group comparison; Wilcoxon rank sum test, * p < 0.05 (2-sided). FD, functional dyspepsia.

Fig. 5.

The elimination rate for PDS and EPS-like symptoms after 12 weeks of test food intake (per-protocol). The percentage of the individuals who experienced the disappearance of PDS symptoms was measured at each time point in the PDS population (a). Similarly, disappearance of EPS-like symptoms was measured in the EPS-like population (b). Group comparison, Fisher's exact test: * p < 0.05 (2-sided); ns, not significant; PDS, postprandial distress syndrome; EPS, epigastric pain syndrome.

Individual FD Symptom Scores and Accompanying Symptom Scores

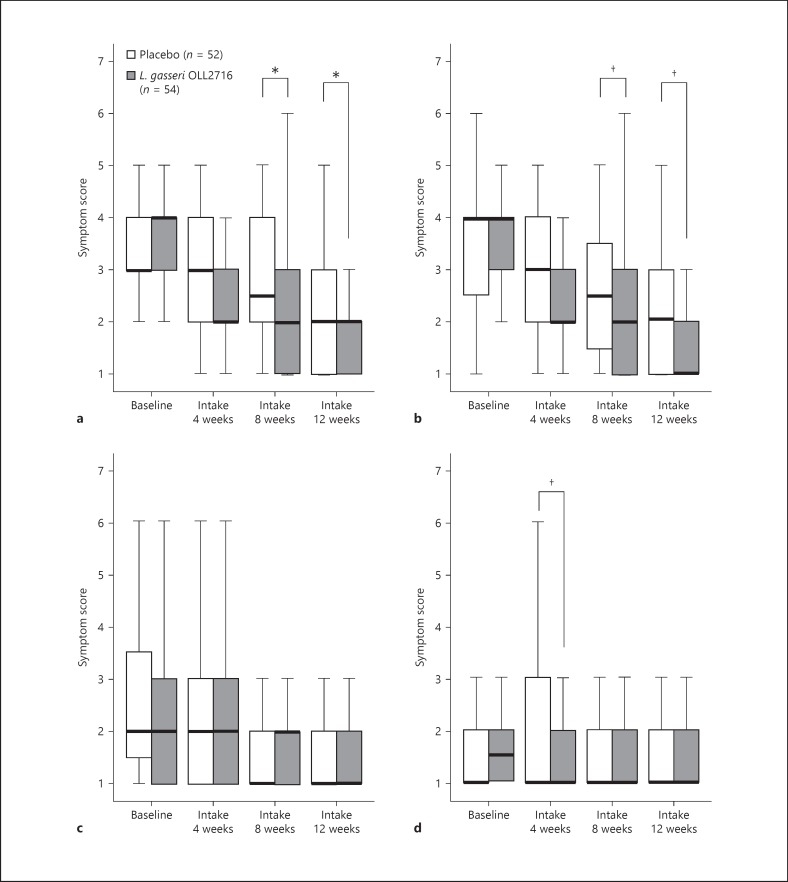

As shown in Figure 6, compared to the scores in the placebo group, the L. gasseri OLL2716 group showed statistically significant improvements in the symptom scores for postprandial fullness (both 8 and 12 weeks, p = 0.042). In addition, the symptom scores for early satiety tended to improve in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group compared to those in the placebo group (8 weeks, p = 0.088; 12 weeks, p = 0.070). Furthermore, compared to those in the placebo group, the symptom scores for epigastric burning tended to improve in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group (4 weeks, p = 0.086). There were no significant group differences or trends in terms of epigastric pain at any time.

Fig. 6.

Individual FD symptom severity across time (per-protocol). The severity of individual FD symptoms was rated from 1 to 7, with 1 representing no symptoms, and higher numbers representing worsening of the symptoms. The severity is shown as a box plot graph (median 25-75 percentile; bar indicating 1.5 times the height of the box). Postprandial fullness (a), early satiety (b), epigastric pain (c), and epigastric burning (d). Group comparison; Wilcoxon rank sum test: †p < 0.10 (2-sided), * p < 0.05 (2-sided). FD, functional dyspepsia.

The results regarding the accompanying symptoms of FD are shown in online supplementary Table 1 (see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000479000). The symptom scores for epigastric bloating showed a statistically significant improvement in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group compared to those in the placebo group (8 weeks, p = 0.032; 12 weeks, p = 0.017). Compared to those in the placebo group, the symptom scores for heartburn showed a statistically significant improvement in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group after 4 and 8 weeks of test food intake, but not after 12 weeks (4 weeks, p = 0.027; 8 weeks, p = 0.020). Compared to the placebo group, the symptom scores for the reflex feeling of gastric acid displayed a statistical trend for improvement in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group after 4 weeks of test food intake, and showed a significant improvement after 8 weeks (4 weeks, p = 0.088; 8 weeks, p = 0.047).

Safety Assessment

A safety assessment was performed using data from the 115 individuals who had ingested the test food product once or more. Two individuals in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group and 5 individuals in the placebo group experienced adverse events. No significant group differences were found in terms of the incidence of adverse events (p = 0.438). Confirmation showed no causal relationship between the test food and the adverse events, and none of the adverse events had any side effects.

Discussion

In assessing the effects of interventions against FD, patient-reported outcomes regarding their experience of the disease are important because of the absence of apparent mechanical abnormalities and established biomarkers [23, 25]. The participant's impression regarding the overall effect on gastric symptoms has thus been used as a primary endpoint in FD clinical trials; the intervention effect is easier to understand, as it is inclusive [21, 22]. This study also used this outcome as the primary endpoint. We found that the participant's impression regarding the overall effect on gastric symptoms was more positive in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group compared to that in the placebo group, with the difference reaching a nonsignificant statistical trend (p = 0.073). Meanwhile, the elimination rate for all 4 major FD symptoms after the 12-week test food intake was significantly higher in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group compared to that in the placebo group (p = 0.048). The participant's impression as the primary endpoint consisted of the response to the question, “How have your overall gastric symptoms been during the past week, compared with your symptoms during the baseline period preceding the intake of the food product?,” which requires the recollection of the symptoms at baseline and includes the influence of symptoms accompanying FD (such as heartburn and belching). Because of this, the participant's impression may have restricted the ability to evaluate FD, reducing the statistical power. In addition, L. gasseri OLL2716-induced improvements were not found for EPS-like symptoms; thus, EPS symptoms might have contributed to the participant's impression to a greater extent, compared to that for PDS symptoms. Moreover, most of the participant's responses in the placebo group were positive regarding the primary endpoint. It is reported that a placebo effect is generally observed in the treatment of FD; however, the use of yogurt as placebo may have provided some improvement to the symptoms of FD. The relationship between functional gastrointestinal disorders and bile acids is a topic of great interest [26]. According to previous studies, the gut microbiota not only excretes bile acids into the feces by promoting deconjugation but also inhibits bile acid synthesis in the liver [27]. Although the effects of yogurt on the gut microbiota may be relatively small [28, 29], improvement of the upper abdominal symptoms may result from a decrease in secretory bile acids in the duodenum.

Motor function abnormalities including delayed gastric emptying cannot explain the etiopathology of PDS in nearly half the cases [30], and in some cases it is associated with conditions such as visceral hypersensitivity [2]. Interestingly, the results of this study indicate that L. gasseri OLL2716 has a greater beneficial effect on PDS symptoms than on EPS-like symptoms. Prokinetic agents improving gastrointestinal motility have been reported to have beneficial effects on PDS [31], and the beneficial actions of L. gasseri OLL2716 might be focused mainly on gastric motility abnormalities (delayed gastric emptying and impaired adaptability to relaxation). Regarding the accompanying symptoms of FD, L. gasseri OLL2716 resulted in a statistically significant improvement in the symptom of heartburn at 8 weeks of test food intake but not at 12 weeks. However, at 12 weeks, both the median values and 25–75 percentiles for heartburn symptom score in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group were minimal (symptom score = 1); therefore, a significant difference between the groups would have probably been more likely if the baseline symptom score in this trial was higher. The reflex feeling of gastric acid was similar. A recent report suggested that reflex symptoms were more severe in the delayed gastric emptying group than in the nondelayed group among female patients [32]; therefore, L. gasseri OLL2716 may be acting to reduce both inflammation and hypersensitivity in the esophagus through a reduction in the amount of reflex (containing gastric acid and bile acid), which is caused by the normalization of gastric emptying. In addition, in the L. gasseri OLL2716 group, there were statistically significant improvements in epigastric bloating; this finding is important because epigastric bloating is considered to be very common among Asian dyspeptic patients [33].

The findings of this study indicate that probiotics have beneficial effects against FD in H. pylori-uninfected individuals; however, the underlying mechanism of action remains unknown. Probiotics have been reported to have beneficial effects against IBS, and their involvement in the amelioration of enhanced permeability in the intestinal mucosa has been indicated as the mechanism of action [8, 9, 10]. Enhanced permeability in the intestinal mucosa affects the enteric, central, and autonomic nervous systems by causing chronic microinflammation [34]. Moreover, patients with FD have recently been reported to have enhanced permeability in the duodenal mucosa and an increase in eosinophilic counts; thus, the duodenum has been a focus of attention as an organ involved in the onset of FD [12, 13, 35]. However, the duodenum is a site where intestinal bacteria are low in abundance, and digestive juices such as biliary acids and pancreatic juice are secreted. Probiotics are believed to result in improved mucosal permeability by ameliorating abnormalities of the intestinal microbiota [8, 9, 10, 11]; however, this cannot be assumed in the duodenum based on general knowledge. While the mechanism of action behind the effects of probiotics against FD remains unknown, probiotics may be directly involved, without microbiota, in the amelioration of the enhanced permeability in the gastric mucosa as shown in previous reports [36, 37]. Although the conditions in the duodenum may not necessarily be suitable for all probiotics, L. gasseri OLL2716-specific characteristics (such as its resistance to gastric acids, ability to grow at low pH, and ability to attach to gastric-derived cultured cells [38]) may be responsible for the demonstrated ameliorating effect on FD. In addition, the effect of L. gasseri OLL2716 on functional bowel disorders (IBS, functional constipation, etc.) is not clear; however, it has been reported that probiotics improve intestinal microbiota, feces shape/bowel movements, and IBS. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate whether L. gasseri OLL2716 is involved in the improvement of bowel disorders and its efficacy in the improvement of FD. Interestingly, a recent report showed that Bifidobacterium and Clostridum, which are both intestinal bacteria, are detected in the gastric juice of patients with FD [39]. In the future, there is a need to elucidate at which sites between the stomach and the intestine L. gasseri OLL2716 acts, and whether indigenous bacterial flora are involved in the process.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small for the assessment of a comprehensive participant-reported outcome as an endpoint. A second limitation was the fact that the ameliorating effect on FD was analyzed using the PP population. A third limitation was that the FD cases were diagnosed based on Rome III criteria [1]. In the Rome IV criteria published in 2016, FD is defined as a condition where any of the 4 symptoms is bothersome for the patient [2]. Despite these limitations, this study is the first of its kind for probiotic research given the RCT design, strict definition of FD, and use of sufficiently reliable outcomes. As a result, we demonstrated that L. gasseri OLL2716 has beneficial effects on FD without H. pylori involvement. H. pylori-associated dyspepsia is minor; therefore, this finding is highly valuable. Moreover, it is also interesting that L. gasseri OLL2716 showed beneficial effects on PDS symptoms, including postprandial fullness and early satiety, as previous studies have shown that it is difficult to treat PDS as well as EPS [2]. For example, proton pump inhibitors are ineffective in relieving PDS symptoms. Acotiamide hydrochloride, based on a procholinergic effect, is recognized to be effective for symptoms of PDS; however, an NNT (number needed to treat) value of 6 is not necessarily adequate. Lastly, this study suggests that the ameliorating effect of L. gasseri OLL2716 on FD may require continuous intake. However, L. gasseri OLL2716-containing yogurt can be used habitually in the daily diet; therefore, it could be useful for health maintenance and promotion or for the prevention of an aggravated condition. In addition, L. gasseri OLL2716 might be useful for the treatment of FD, especially in combination with acid secretion inhibitors or prokinetics.

Disclosure Statement and Source of Funding

T.O., A.K., and M.U. are employees of Meiji Co., Ltd. A.T. and Y.K. are currently receiving a grant from Meiji Co., Ltd. N.U. and K.I. have received honoraria from Meiji Co., Ltd. H.S. has received expenses related to the commission of this study. Costs related to this study were defrayed by Meiji Co., Ltd.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank HUMA R&D Co., Ltd., who supported this clinical trial as the contract research organization. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing and Publication Support. We thank the members of the Fermented Milk Department in the Research and Development Labs at Meiji Co., Ltd., which supplied the test food products.

References

- 1.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Holtmann G, Hu P, Malagelada JR, Stanghellini V. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, Malagelada JR, Suzuki H, Tack J, Talley NJ. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380–1392. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aro P, Talley NJ, Agréus L, Johansson SE, Bolling-Sternevald E, Storskrubb T, Ronkainen J. Functional dyspepsia impairs quality of life in the adult population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1215–1224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drossman DA. Presidential address: Gastrointestinal illness and the biopsychosocial model. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:258–267. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Oudenhove L, Crowell MD, Drossman DA, Halpert AD, Keefer L, Lackner JM, Murphy TB, Naliboff BD, Levy RL. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1355–1367. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki H, Mori H. Helicobacter pylori: Helicobacter pylori gastritis - a novel distinct disease entity. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:556–557. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mearin F, Pérez-Oliveras M, Perelló A, Vinyet J, Ibañez A, Coderch J, Perona M. Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome after a Salmonella gastroenteritis outbreak: one-year follow-up cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:98–104. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moayyedi P, Ford AC, Talley NJ, Cremonini F, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Brandt LJ, Quigley EM. The efficacy of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Gut. 2010;59:325–332. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.167270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukudo S, Kaneko H, Akiho H, Inamori M, Endo Y, Okumura T, Kanazawa M, Kamiya T, Sato K, Chiba T, Furuta K, Yamato S, Arakawa T, Fujiyama Y, Azuma T, Fujimoto K, Mine T, Miura S, Kinoshita Y, Sugano K, Shimosegawa T. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:11–30. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-1017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel RM, Myers LS, Kurundkar AR, Maheshwari A, Nusrat A, Lin PW. Probiotic bacteria induce maturation of intestinal claudin 3 expression and barrier function. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tana C, Umesaki Y, Imaoka A, Handa T, Kanazawa M, Fukudo S. Altered profiles of intestinal microbiota and organic acids may be the origin of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:512–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01427.x. e114-e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talley NJ, Walker MM, Aro P, Ronkainen J, Storskrubb T, Hindley LA, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Agréus L. Non-ulcer dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophilia: an adult endoscopic population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1175–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanheel H, Vicario M, Vanuytsel T, Van Oudenhove L, Martinez C, Keita ÅV, Pardon N, Santos J, Söderholm JD, Tack J, Farré R. Impaired duodenal mucosal integrity and low-grade inflammation in functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2014;63:262–271. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, Delaney B, Harris A, Innes M, Oakes R, Wilson S, Roalfe A, Bennett C, Forman D. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;19:CD002096. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002096.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takagi A, Yanagi H, Ozawa H, Uemura N, Nakajima S, Inoue K, Kawai T, Ohtsu T, Koga Y. Effects of Lactobacillus gasseri OLL2716 on Helicobacter pylori-associated dyspepsia: a multicenter randomized double-blind controlled trial. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:7490452. doi: 10.1155/2016/7490452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomi A, Iino T, Nonaka C, Miyazaki K, Ishikawa F. Health benefits of fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium bifidum YIT 10347 on gastric symptoms in adults. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98:2277–2283. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-9158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urita Y, Goto M, Watanabe T, Matsuzaki M, Gomi A, Kano M, Miyazaki K, Kaneko H. Continuous consumption of fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium bifidum YIT 10347 improves gastrointestinal and psychological symptoms in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Biosci Microbiota Food Health. 2015;34:37–44. doi: 10.12938/bmfh.2014-017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki T, Masui A, Nakamura J, Shiozawa H, Aoki J, Nakae H, Tsuda S, Imai J, Hideki O, Matsushima M, Mine T, Tamura A, Ohtsu T, Asami Y, Takagi A. Yogurt containing Lactobacillus gasseri mitigates aspirin-induced small bowel injuries: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Digestion. 2017;95:49–54. doi: 10.1159/000452361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hongo M, Harasawa S, Mine T, Sasaki I, Matsueda K, Kusano M, Hanyu N, Nakada K, Shibata C. Large-scale randomized clinical study on functional dyspepsia treatment with mosapride or teprenone: Japan Mosapride Mega-Study (JMMS) J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:62–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitamura Y, Yoshihara M, Ito M, Boda T, Matsuo T, Kotachi T, Tanaka S, Chayama K. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis by serum pepsinogen levels. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1473–1477. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsueda K, Hongo M, Tack J, Saito Y, Kato H. A placebo-controlled trial of acotiamide for meal-related symptoms of functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2012;61:821–828. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki H, Matsuzaki J, Fukushima Y, Suzaki F, Kasugai K, Nishizawa T, Naito Y, Hayakawa T, Kamiya T, Andoh T, Yoshida H, Tokura Y, Nagata H, Kobayakawa M, Mori M, Kato K, Hosoda H, Takebayashi T, Miura S, Uemura N, Joh T, Hibi T, Tack J, Rikkunshito Study Group Randomized clinical trial: rikkunshito in the treatment of functional dyspepsia - a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:950–961. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Chiba N, Armstrong D, Barkun AN, Thomson AB, Mann V, Escobedo S, Chakraborty B, Nevin K. Validation of a 7-point global overall symptom scale to measure the severity of dyspepsia symptoms in clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:521–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwakiri R, Tominaga K, Furuta K, Inamori M, Furuta T, Masuyama H, Kanke K, Nagahara A, Haruma K, Kinoshita Y, Higuchi K, Takahashi S, Kusano M, Iwakiri K, Kato M, Hongo M, Hiraishi H, Watanabe S, Miwa H, Naito Y, Fujimoto K, Arakawa T. Randomised clinical trial: rabeprazole improves symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:729–740. doi: 10.1111/apt.12444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irvine EJ, Tack J, Crowell MD, Gwee KA, Ke M, Schmulson MJ, Whitehead WE, Spiegel B. Design of treatment trials for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1469–1480. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Appleby RN, Walters JR. The role of bile acids in functional GI disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:1057–1069. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sayin SI, Wahlström A, Felin J, Jäntti S, Marschall HU, Bamberg K, Angelin B, Hyötyläinen T, Orešič M, Bäckhed F. Gut microbiota regulates bile acid metabolism by reducing the levels of tauro-beta-muricholic acid, a naturally occurring FXR antagonist. Cell metabolism. 2013;17:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elli M, Callegari ML, Ferrari S, Bessi E, Cattivelli D, Soldi S, Morelli L, Goupil Feuillerat N, Antoine JM. Survival of yogurt bacteria in the human gut. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2006;72:5113–5117. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02950-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iino H, Aoki M, Shigeno C, Nishimuta M, Terahara M, Kume A, Mizumoto K, Mizoguchi C, Koizumi A, Takeda M, Ozaki S, Sasaki H, Uchida M, Itou H. A placebo-controlled double-blind comparative study to assess the effect of ingesting bulgarian yogurt on fecal Bifidobacteria counts. Jpn J Nutr Diet. 2013;71:171–184. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarnelli G, Caenepeel P, Geypens B, Janssens J, Tack J. Symptoms associated with impaired gastric emptying of solids and liquids in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:783–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsueda K, Hongo M, Tack J, Aoki H, Saito Y, Kato H. Clinical trial: dose-dependent therapeutic efficacy of acotiamide hydrochloride (Z-338) in patients with functional dyspepsia - 100 mg t.i.d. is an optimal dosage. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01449.x. e173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mori H, Suzuki H, Matsuzaki J, Taniguchi K, Shimizu T, Yamane T, Masaoka T, Kanai T. Gender difference of gastric emptying in healthy volunteers and patients with functional dyspepsia. Digestion. 2017;95:72–78. doi: 10.1159/000452359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miwa H, Ghoshal UC, Fock KM, Gonlachanvit S, Gwee KA, Ang TL, Chang FY, Hongo M, Hou X, Kachintorn U, Ke M, Lai KH, Lee KJ, Lu CL, Mahadeva S, Miura S, Park H, Rhee PL, Sugano K, Vilaichone RK, Wong BC, Bak YT. Asian consensus report on functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:626–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.07037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbara G, Feinle-Bisset C, Ghoshal UC, Quigley EM, Santos J, Vanner S, Vergnolle N, Zoetendal EG. The intestinal microenvironment and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1305–1318. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker MM, Aggarwal KR, Shim LS, Bassan M, Kalantar JS, Weltman MD, Jones M, Powell N, Talley NJ. Duodenal eosinophilia and early satiety in functional dyspepsia: confirmation of a positive association in an Australian cohort. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:474–479. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uchida M, Kurakazu K. Yogurt containing Lactobacillus gasseri OLL2716 exerts gastroprotective action against [correction of agaisnt] acute gastric lesion and antral ulcer in rats. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;96:84–90. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fpj04027x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akama F, Nishino R, Makino S, Kobayashi K, Kamikaseda K, Nagano J, Koga Y. The effect of probiotics on gastric mucosal permeability in humans administered with aspirin. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:831–836. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.574730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimura K, Sakamoto I, Igarashi M, Takagi A, Miwa T, Aiba Y, Koga Y. Development of probiotics for Helicobacter pylori infection. Biosci Microflora. 2003;22:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakae H, Tsuda A, Matsuoka T, Mine T, Koga Y. Gastric microbiota in the functional dyspepsia patients treated with probiotic yogurt. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:e000109. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2016-000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]