Summary

Background

Chronic antigen exposure and/or ageing increases the frequency of T-box expressed in T cells (T-bet)-expressing B-lymphocytes in mice. The frequency and significance of B-cell T-bet expression during chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection in human subjects has never been described.

Methods

Healthy controls, cirrhotic and noncirrhotic HCV-infected patients, and non-HCV patients with cirrhosis were recruited. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were phenotyped for expression of T-bet and related markers by flow cytometry. In a subset of patients who underwent antiviral therapy and were cured of HCV infection (sustained virological response), the dynamics of T-bet expression in B cells was monitored. After cure, convalescent B cells were tested for T-bet expression after re-exposure to infected plasma or recombinant HCV proteins.

Results

Forty-nine patients including 11 healthy donors, 30 hepatitis C-infected individuals (nine with liver cancer, 13 with cirrhosis, eight without cirrhosis) and eight patients with cirrhosis due to non-HCV-related cause were recruited. We found that B cells in patients with chronic HCV exhibited increased frequency of T-bet+ B cells relative to noninfected individuals (median 11.5% v. 2.2%, P<.0001) but that there were no significant differences between noncirrhotic, cirrhotic and cancer-bearing infected individuals. T-Bet+ B cells expressed higher levels of CD95, CXCR3, CD11c, CD267 and FcRL5 compared to T-bet− B cells and predominantly exhibit a tissue-like memory CD27− CD21− phenotype independent of HCV infection. T-bet+ B cells in HCV-infected patients were more frequently class-switched IgD−IgG+ (40.4% vs. 26.4%, P=.012). Resolution of HCV infection with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy leads to a marked reduction in the frequency of T-bet+ B cells (median 14.1% pretreatment v. 6.7% end of treatment v. 6.1% SVR12, P≤.01). Re-exposure of convalescent (cured) B cells to viremic plasma and recombinant HCV E2 protein led to re-expression of T-bet.

Conclusion

Chronic antigenemia in chronic HCV infection induces and maintains an antigen-specific T-bet+ B cell. These B cells share markers with tissue-like memory B cells. Antigen-driven T-bet expression may be a critical suppressor of B-cell activation in chronic HCV infection.

Keywords: age-associated B cells (ABCs), B cell, cirrhosis, FcRL5, hepatitis C, humoral immunity, T-bet

1 INTRODUCTION

While its role is most understood in the context of T-cell differentiation, the T-box transcriptional factor T-bet also plays an important role in B-cell differentiation and is frequently expressed in neoplastic human B cells.1,2 T-bet induction in B cells requires antigen-specific cross-linking of the B-cell receptor as well as type I/II IFN-mediated or IL-12-family receptor-mediated activation of STAT1 or STAT43,4 in combination with TLR signalling.5,6 Once expressed, T-bet appears to regulate Ig class switching,3,6–9 B-cell IFNγ production,3,4 and differentiation into antiviral-effector ADCC-inducing CD11b+/CD11c+ B cells critical for acute viral control.5

During chronic antigen exposure and/or ageing, the frequency of T-bet+ B cells increases in mice.9,10 T-bet expression has been used to define age-associated B cells (ABCs) in mice, a population found in blood, spleen and bone marrow that manifests a distinct surface phenotype (expressing CD11c, TACI(CD267), CD95(Fas) and CD138) and that plays an important role as antigen presenting cells (APCs) that skew naive CD4 T cells to a Th1 or Th17 phenotype.10–12 In human subjects, CD27−CD21−/lo tissue-like memory B cells that share some phenotypic similarities with ABCs10 have been shown to be expanded in chronic viral infections and rheumatological disorders.13–17 Recently, Fc receptor-like (FcRL5) has been identified as a potential surface marker of antigen-specific tissue-like memory cells, possibly associated with T-bet upregulation, in healthy adults and individuals with P. falciparum infection.18,19 Increased FcRL5 expression on CD27+CD21−/low marginal zone B cells has been previously shown in chronic hepatitis C patients with cryoglobulinemic vasculitis,20 but the tissue-like memory population has not previously been evaluated for FcRL5 or T-bet expression specifically in this disease.

We previously identified an increase in CD27−CD21− tissue-like memory B cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C with and without cirrhosis.17 We surmised that these CD27−CD21− tissue-like memory B cells might represent the human correlate of T-bet+ ABC cells. To study this hypothesis, we recruited patients with chronic hepatitis C infection at various stages of liver disease progression and healthy controls. We found that HCV-infected patients with nonfibrotic liver disease, cirrhosis and liver cancer all harbour expanded populations of T-bet+ B cells relative to healthy donors and nonviral-related cirrhosis. T-bet+ B cells predominantly exhibit markers of tissue-like memory B cells. Taking advantage of the natural experiment of virological cure in patients undergoing direct-acting antiviral therapy, we found that sustained viral clearance led to a marked reduction in circulating T-bet+ cells. Re-exposure of convalescent B cells to HCV antigens led to re-expression of T-bet suggesting that chronic antigenemia in chronic HCV infection induces antigen-specific T-bet+ ABCs.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Patients

Subjects and controls were recruited from the Gastroenterology Clinic at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veterans Affairs Medical Center following informed consent on an institutional review board-approved protocol. Viral hepatitis, alcohol abuse, haemochromatosis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis diagnoses were obtained from clinical records. Standard genotype-specific direct-acting antiviral (DAA) combination therapies for chronic hepatitis C including sofosbuvir plus ribavirin (genotype 2), ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (±ribavirin) (genotype 1) or dasabuvir/ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir (±ribavirin) (genotype 1) for 12 weeks were administered during routine clinical care.

2.2 Cell isolation and preparation

One hundred to one hundred and fifty millilitre of peripheral blood was obtained, from which 100–200 million peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated using Ficoll-Histopaque (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) density gradient centrifugation. B cells were purified from 100×106 PBMC by negative selection using the MACS B-cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). B cells were >95% as determined by flow cytometry and were plated in 96-well plates in RPMI1640 with L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% human AB serum (Sigma Inc.), 1.5% HEPES (Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen).

2.3 Antibodies and flow cytometry

All data were acquired on FACSCanto (BD: Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) and analysed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA) using cut-offs based on isotype antibody staining. All antibodies were purchased from Becton Dickinson (BD: Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) except for anti-FcRL5 (CD307e APC, clone 509f6; Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and fixable Live/Dead Aqua Staining kit (Invitrogen).

2.4 Re-induction of T-bet expression

A total of 1×105 B cells from HCV-infected patients who achieved SVR were cultured in 50% complete medium supplemented with 50% autologous plasma (HCV pretreatment and after 12 weeks post-treatment) and heterologous genotype 1 and 2 plasma (HCV pretreatment). In some experiments, B cells were preincubated for 30 minutes with anti-Fc receptor mAb (BioLegend). In some experiments, B cells were cultured with 10 μg/ml rE2 protein from J6 virus (generously provided by J. Marcotrigiano), 10 μg/ml rHCV core protein (Chiron Corporation, Emeryville, CA, USA) and 10 μg/ml rHBcAg protein (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) for 18 hours, then stained for T-bet expression.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Median values for clinical and immunologic parameters were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis or Wilcoxon rank sum test. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 12 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). P-values of <.05 were considered significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patient characteristics

The study cohort comprised of 49 subjects, 11 healthy donors, eight patients with cirrhosis due to non-HCV-related cause, eight HCV patients without advanced fibrosis (based on Fibrosure F0–1, Fibroscan<9 kPA, or Ishak Fibrosis Score<3/6), 13 with HCV and liver cirrhosis and nine with HCV, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (Table 1). Eight HCV patients with cirrhosis were observed during direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy; all eight were successfully cured with standard genotype-specific all-oral therapies (three with sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for 12 weeks, five with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for 12 weeks). Patients with cirrhosis, particularly those with cancer, were slightly older than healthy donors (median age 62 versus 55 years, P=.04) but similar in age to non-HCV cirrhotic patients that served as an additional control group. As expected due to portal hypertension, median platelet counts were lower in the cirrhosis subgroups but patients were in general well compensated with normal serum total bilirubin and albumin levels.

TABLE 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy donors | Non-cirrhotic HCV | HCV cirrhosis | HCV cirrhosis with HCC | Non-HCV cirrhosis | P-value | |

| N | 11 | 8 | 13 | 9 | 8 | |

| Age (IQR) | 55 (50–63) | 60 (58–62) | 63 (59–66) | 67 (63–68) | 62 (55–67) | .04 |

| Gender (% Male) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | NS |

| Ethnicity | Six Black/five White |

Six Black/two White |

Seven Black/six White |

Five Black/three White/one Hispanic |

Two Black/six White |

.43 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL (IQR) | 0.5 (0.4–1.0) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.7 (0.6–1.3) | .31 |

| Serum albumin, g (IQR) | 4.0 (3.7–4.2) | 4.4 (4.0–4.5) | 3.7 (3.6–3.9) | 3.6 (3.3–4.1) | 4.2 (3.7–4.5) | .02 |

| Platelet, k/mm3 (IQR) | 231 (184–264) | 232 (178–258) | 160 (111–191) | 167 (132–225) | 161 (112–196) | .002 |

| HCV genotype or disease | N/A | 4 1a | 5 1a | 3 1a | 3 EtOH | |

| 4 1b | 3 1b | 5 1b | 2 NASH/1 NASH+EtOH | |||

| 5 2 | 1 Unknown | 2 HFE | ||||

3.2 Chronic hepatitis C infection is associated with increased frequency of class-switched T-bet+ B cells with a tissue-like memory phenotype

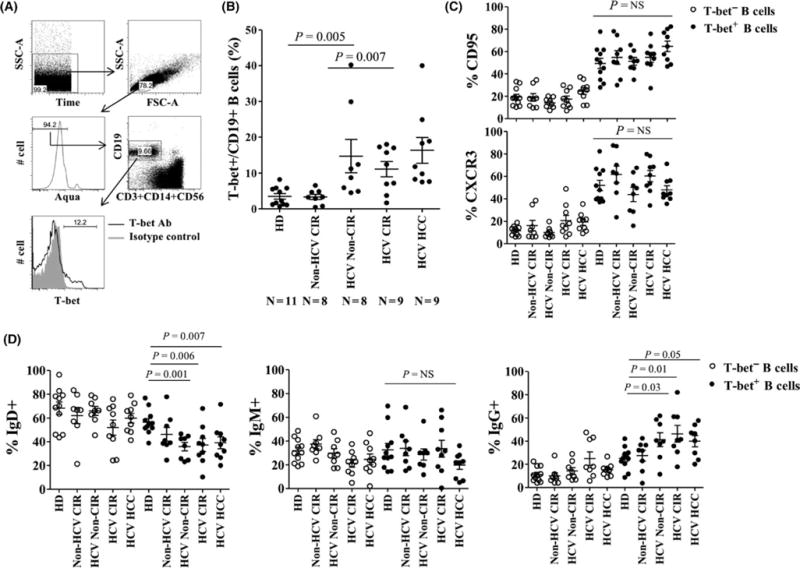

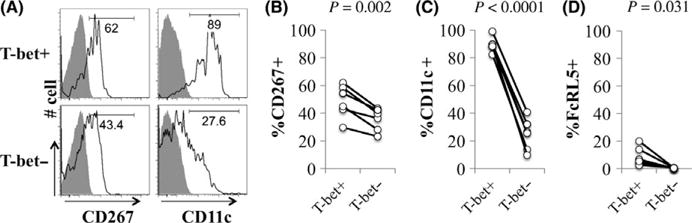

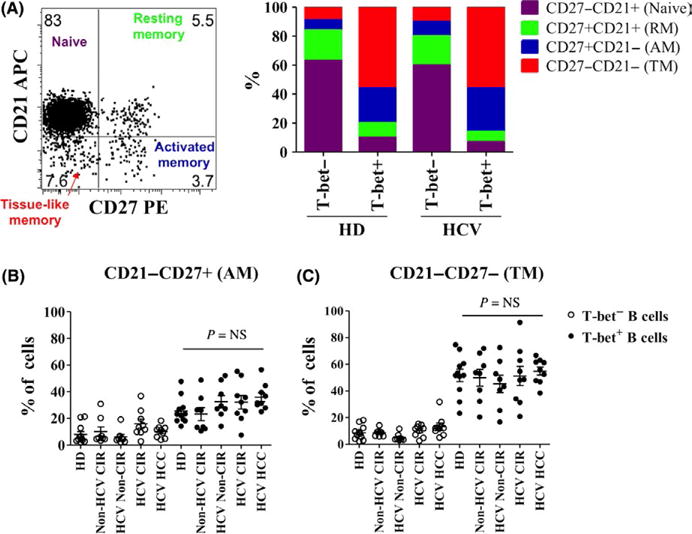

The gating strategy for identifying B cells and quantifying T-bet is shown in Figure 1A. Among patients with viral hepatitis, with or without cirrhosis, the frequency of circulating T-bet+ B cells was significantly increased (median 11.5% v. 2.2%, P<.001). There were no significant differences across HCV-infected subgroups. Notably, non-HCV-infected cirrhotic patients exhibited similar frequencies of T-bet+ B cells as healthy individuals discounting a role of liver disease itself in inducing this cell population. Similar to previous descriptions of age-associated B cells (ABCs), T-bet+ B cells expressed markedly increased levels of CD95 and CXCR3 relative to T-bet-B cells independent of the patient subset Figure 1C. In hepatitis C-infected subjects, the majority of T-bet+ B cells manifested a class-switched phenotype with loss of sIgD and increased expression of sIgG (Figure 1D). By contrast, in healthy donors sIgD was expressed at a similar frequency in T-bet+ and T-bet− B cells and sIgG frequency was lower. Similar to ABCs in mice, human T-bet+ B cells expressed increased levels of CD11c+ (median 88.7% v. 26.1%, P<.0001) and were more likely to express the BAFF receptor TACI (CD267) relative to T-bet− B cells (Figure 2B–C). While FcRL5 expression was more common in T-bet+ cells, only a mean of 8.7% of T-bet+ B cells expressed FcRL5 (Figure 2D); 54±24% of FcRL5+ cells expressed T-bet, and of these 68±4.1% expressed sIgG (data not shown). A total of 75–80% of T-bet+ B cells are found in CD21− fractions, with 20–30% having an activated memory phenotype (CD27+CD21−) but the majority a tissue-like memory CD27−CD21− phenotype (Figure 3A–C). In summary, T-bet+ B cells are significantly expanded in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection, irrespective of liver disease stage, share a predominantly IgG-class-switched CD27−CD21− tissue-like memory cell phenotype and express some markers, particularly CD11c, CXCR3 and CD95, previously associated with ageing B cells in mice.

FIGURE 1.

Class-switched T-bet-expressing B cells circulate in higher frequency in chronic hepatitis C infection. (A) Representative FACS analyses and (B) quantification of T-bet expression on CD19+ B cells in healthy donor (HD), non-HCV cirrhotics (non-HCV CIR), noncirrhotic HCV-infected patients (non-CIR HCV), HCV patients with cirrhosis (HCV CIR) and HCV cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCV HCC). Quantification of CD95 (C), CXCR3 (C), IgD (D), IgM (D)and IgG (D) expression on T-bet+ B cells and T-bet-B cells across patient cohorts. P-values derived using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Error bars reflect mean and standard error of the mean

FIGURE 2.

T-bet-expressing B cells exhibit markers previously associated with age-associated B cells. (A) Representative histograms of CD11c and CD267 expression on T-bet+ B cells and T-bet− B cells in HCV-infected patients. Grey histogram shows isotype control. Relative quantification of (B) CD267, (C) CD11c and (D) FcRL5 on T-bet+ B cells and T-bet− B cells in HCV-infected patients. P-values derived using matched pair Wilcoxon signed-Rank

FIGURE 3.

T-bet-expressing B cells predominantly exhibit a tissue-like memory phenotype. (A) Representative dot plot and bar chart representing percentages of T-bet+ and T-bet− cells from healthy donors and hepatitis C-infected subjects that can be characterized as CD27−CD21+ (Naive), CD27+CD21+ (Resting Memory), CD27+CD21− (Activated Memory) or CD27−CD21− (tissue-like memory) B cells. Quantification of activated memory (B) and tissue-like memory (B) B cell frequency in T-bet+ B cells and T-bet− B cells in healthy donor (HD), non-HCV cirrhotics (non-HCV CIR), noncirrhotic HCV-infected patients (non-CIR HCV), HCV cirrhotics (HCV CIR) and HCV cirrhotics with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCV HCC). P-values by the Kruskal-Wallis test

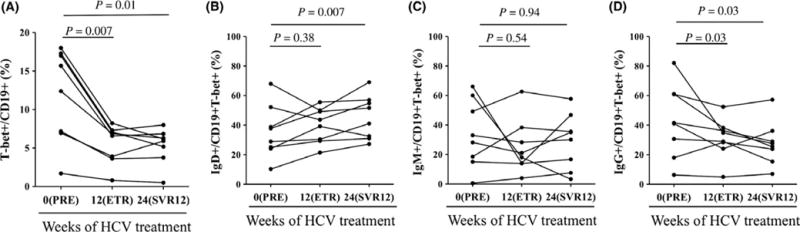

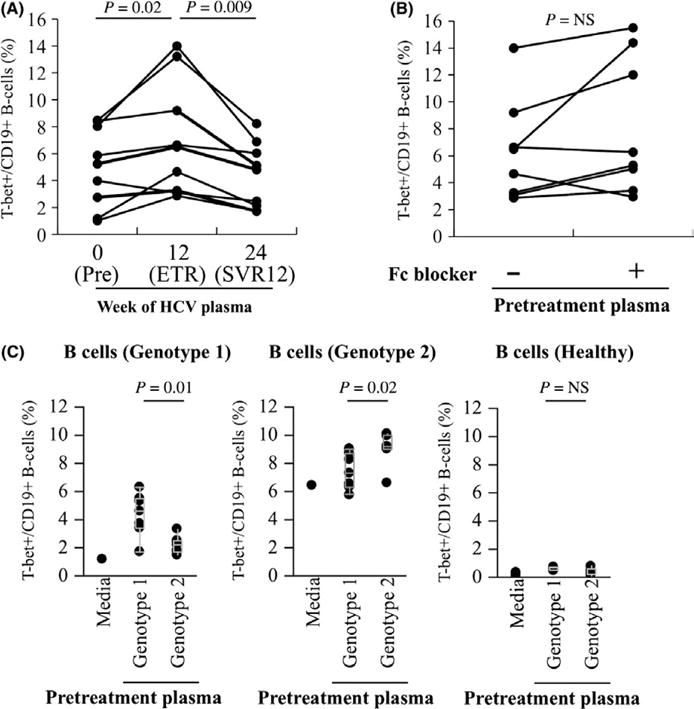

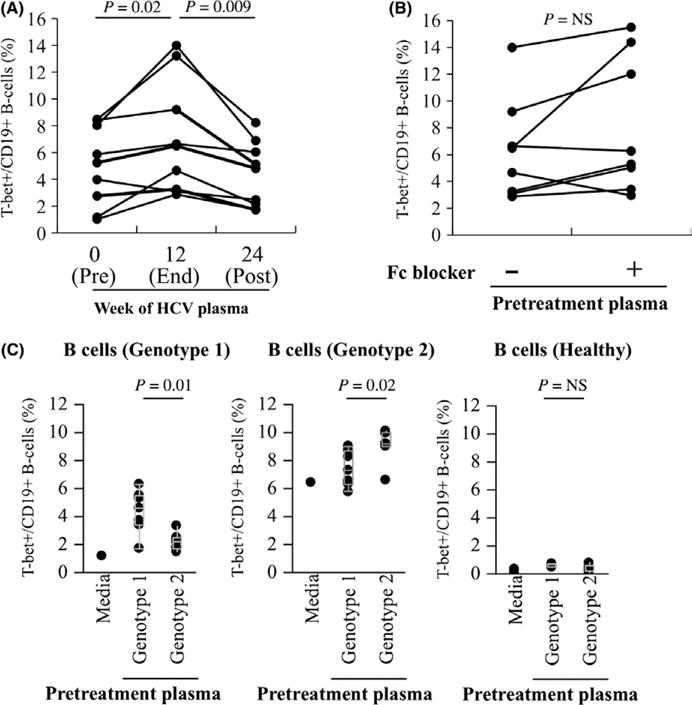

3.3 Hepatitis C eradication is associated with decreases in peripheral T-bet+ B cells

Eight patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis were observed for changes in the frequency of T-bet+ B cells before, at the completion, and twelve weeks after completion of direct-acting antiviral therapy. All patients were successfully cured (sustained virological response at week 12 after therapy—SVR12). There were marked and sustained reductions in the frequency of T-bet+ B cells at the end of therapy that were durable at SVR12 (median 14.1% v. 6.7% v. 6.1%, P<.01) (Figure 4A). Virological cure was associated with a reduction in sIgG+ T-bet+ B cells and a relative increase in sIgD+ T-bet+ B cells (Figure 4B–D) in the contracted T-bet+ population suggesting specific disappearance of sIgG+ but not sIgD+ T-bet+ B cells related to HCV clearance.

FIGURE 4.

Viral eradication leads to reduction in circulating sIgG+ T-bet+ B cells. (A) Quantification of T-bet expression on CD19+ B cells in HCV-infected patients after in vivo treatment with antiviral therapy. Pretreatment (week 0), end of treatment response (ETR—week 12) and week 24 (12 weeks post-treatment also termed sustained virological response at 12 weeks—SVR12) time points shown. Quantification of sIgD (B), sIgM (C) and sIgG (D) expression on T-bet+ B cells in HCV-infected patients after in vivo treatment with antiviral therapy. P-values by the matched-pairs Wilcoxon signed-rank test

3.4 Evidence for antigen-specific regulation of T-bet expression

To test whether or not T-bet expression in B cells is regulated by HCV viraemia, we first exposed post-SVR12 convalescent B cells from cured patients to autologous pretreatment viremic or post-treatment aviremic plasma. As shown in Figure 5A, there was a statistically significant increase in T-bet expression after exposure of convalescent B cells to autologous viremic plasma (median 7.0% v. 4.3%, P=.009). This increase did not appear to be mediated by immune complexes, as blockade of B-cell Fc receptors had not impact on T-bet upregulation (Figure 5B). The upregulation of T-bet was sequence-specific; convalescent B cells from genotype 1 patients exhibited much more significant upregulation of T-bet when exposed to heterologous genotype 1-viremic plasma than to genotype 2-viremic plasma, and vice versa (Figure 5C–D). While recombinant HCV proteins were less effective at upregulating T-bet in convalescent B cells, HCV E2 but not HCV Core (nc22) led to upregulation of T-bet (Figure 6) suggesting that antigen present on the surface of viral particles is the primary antigen responsible for regulation of T-bet in HCV-specific B cells.

FIGURE 5.

Re-exposure of convalescent B cells to virus leads to sequence-specific upregulation of T-bet expression. (A) Purified convalescent B cells from HCV-infected patients who achieved SVR12 (cure) were cultured in 50% complete medium supplemented with 50% autologous plasma (HCV pretreatment and after 12 weeks post-treatment) for 18 h, and cells were then stained for T-bet expression. (B) Impact of blocking anti-Fc receptor mAb on the expression of T-bet on convalescent B cells cocultured with autologous plasma (HCV pretreatment) for 18 h. (C) Convalescent B cells from genotype 1 (far left), genotype 2 (centre) or healthy controls (right) were cultured in 50% complete medium supplemented with 50% heterologous genotype 1 and 2 plasma (HCV pretreatment) for 18 h, and cells were then stained for T-bet expression. Representative data from three separate experiments with different B-cell donors are shown. P-values by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test

FIGURE 6.

Viral envelope protein to a greater degree than viral core protein induces upregulation of T-bet in convalescent B cells. Purified convalescent B cells in HCV-infected patients after cure of infection (black lines) or healthy controls (grey lines) were cultured with 10 μg/mL rE2 protein from J6 virus (A), 10 μg/mL rHCV core protein (NC22) (B) and 10 μg/mL rHBcAg protein (HBV core protein) (C) for 18 h, and cells were then stained for T-bet expression. P-values by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for HCV-infected patients

4 DISCUSSION

Chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection in humans is characterized by chronic high-level viral production leading to ongoing exposure of HCV-specific adaptive immune cells to persistent antigenic stimulation. We previously identified a modest expansion of CD27−CD21− hypoproliferative B cells associated with viral-induced but not metabolic cirrhosis and noncirrhotic chronic viral infection.17 We now extend these observations to demonstrate that chronic HCV infection induces the expression of the transcription factor T-bet in cells that largely share the CD27−CD21− tissue-like memory phenotype. Furthermore, these T-bet+ B cells share markers of age-associated B cells, expressing CD11c, CD267, CD95 and CXCR3. Unlike those found in age-matched donors, T-bet+ B cells in HCV patients display a class-switched sIgD−sIgG+ memory phenotype. Cure of hepatitis C infection not only reduced the overall frequency of T-bet+ B cells but specifically the reduction in class-switched sIgD−sIgG+ T-bet+ B cells.

In mice, T-bet+ B cells have been associated with ageing and display CD11c, TACI(CD267), CD95(Fas), CXCR3 and CD138.9,10 We found that T-bet− B cells in humans largely shared this phenotype irrespective of health or hepatitis. In mice, T-bet+ age-associated B cells act as critical antigen presenting cells (APCs) driving naive CD4 T cells towards a Th1 or Th17 phenotype.10–12 A critical limitation of this work is that we were technically unable to isolate human T-bet+ B cells to assess APC function due to the inability to isolate T-bet+ B cells utilizing specific surface markers or via transient overexpression of T-bet. We explored using FcRL5, previously associated with “atypical” CD27−CD21− memory B cells in P. falciparum infections21 and marginal zone B cells in HCV-associated cryoglobulinemia,20 to isolate T-bet+ B cells but found that while FcRL5+ B cells frequently express T-bet, only a small minority of T-bet+ cells express FcRL5. Thus, while phenotypically similar to ABCs, we could not fully confirm functional homology of virus-induced T-bet+ B cells and ABCs. Future work should focus on determining whether the T-bet-expression and the hypoproliferative phenotype of human CD27−CD21− tissue-like memory B cells are related.

In murine and human tonsillar B cells, cross-linking of the B-cell receptor by antigen combined with activation of STAT1 or STAT43,4,6 and/or toll-like receptor signalling5,6 appears necessary for efficient T-bet induction. Our data support that HCV envelope proteins drive T-bet expression in human B cells through interaction with the B-cell receptor as evidenced by the following: (i) a reduction in the frequency of T-bet+ B cells after therapeutic elimination of virus; (ii) sequence-specific upregulation of T-bet in convalescent B cells (which would not be expected if HCV E2 ligation of CD81 was directly causative); (iii) lack of impact of Fc blockade on the re-upregulation of T-bet upon antigen exposure (suggesting limited role of circulating immune complexes); and (iv) the predominant reduction in class-switched IgG+ T-bet+ B cells after cure. We cannot exclude that reduced inflammatory mediators or chemokines associated with resolution of hepatitis could also contribute to reduction in T-bet+ expression in B cells, particularly if those mediators increase concomitant activation of STAT1 or STAT4.

Few data exist regarding T-bet expression peripheral lymphocytes in chronic HCV infection. In acute HCV infection, inadequate T-cell T-bet induction has been implicated in the failure of induction of Th1 responses and failure to resolve acute infection.22 Our data cannot address when in the natural course of acute-to-chronic HCV infection that B-cell T-bet induction occurs, as all of our patients were long-term infected individuals. In early acute HCV infection, there is typically rapid development of viral envelope escape mutants that outpaces the capacity of affinity maturation of neutralizing antibody producing B-cell clones.23 As HCV evolves into persistence, the pace of viral escape slows24,25 suggesting development of regulatory processes to reduce ongoing B-cell affinity maturation. We postulate that T-bet induction in B cells could contribute to this regulation. Recent data from mice from the LCMV model of acute-to-chronic viral infection suggest that early B-cell T-bet expression not only controls murine IgG2a expression but also may impact Ig glycosylation, B-cell homing and B-cell activation.9 Future work should explore the kinetics of B-cell T-bet expression in the early natural history of acute-to-chronic HCV infection with relation to resolution or persistence of infection and the generation of neutralizing antibodies.

5 CONCLUSION

Chronic antigen exposure in hepatitis C infection is associated with expansion of IgD−IgG+ T-bet+ B cells that share some features of ageing-associated B cells. Resolution of HCV infection with direct antiviral therapy leads to a marked reduction in the frequency of T-bet+ B cells, but T-bet rapidly is re-expressed upon B-cell re-exposure to viral antigens. Long-term antigen exposure through chronic BCR-ligation may trigger a T-bet-mediated regulatory programme limiting proliferation, preventing hyperactivation and generating a tissue-like memory phenotype in peripheral B cells in chronic human infections.

Acknowledgments

Funding information

This work was supported by the VA Merit I01 CX000981 (DEK). The content of this article does not reflect the views of the VA or of the US Government.

Abbreviations

- BAFF

B-cell activating factor

- CIR

cirrhotic group

- HD

healthy donor

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- T-bet

T-box Expressed in T cells

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Li-Yuan Chang performed experiments and procedures and participated in writing of manuscript. Yonghai Li contributed to experiments and procedures. David E. Kaplan developed concept and study design and participated in writing of article.

References

- 1.Dorfman DM, Hwang ES, Shahsafaei A, Glimcher LH. T-bet, a T-cell-associated transcription factor, is expressed in a subset of B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:292–297. doi: 10.1309/AQQ2-DVM7-5DVY-0PWP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harashima A, Matsuo Y, Drexler HG, et al. Transcription factor expression in B-cell precursor-leukemia cell lines: preferential expression of T-bet. Leuk Res. 2005;29:841–848. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durali D, de Goer de Herve MG, Giron-Michel J, Azzarone B, Delfraissy JF, Taoufik Y. In human B cells, IL-12 triggers a cascade of molecular events similar to Th1 commitment. Blood. 2003;102:4084–4089. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Goer de Herve MG, Durali D, Dembele B, et al. Interferon-alpha triggers B cell effector 1 (Be1) commitment. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubtsova K, Rubtsov AV, van Dyk LF, Kappler JW, Marrack P. T-box transcription factor T-bet, a key player in a unique type of B-cell activation essential for effective viral clearance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E3216–E3224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312348110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larousserie F, Charlot P, Bardel E, Froger J, Kastelein RA, Devergne O. Differential effects of IL-27 on human B cell subsets. J Immunol. 2006;176:5890–5897. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng SL, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH. T-bet regulates IgG class switching and pathogenic autoantibody production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5545–5550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082114899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu N, Ohnishi N, Ni L, Akira S, Bacon KB. CpG directly induces T-bet expression and inhibits IgG1 and IgE switching in B cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:687–693. doi: 10.1038/ni941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnett BE, Staupe RP, Odorizzi PM, et al. Cutting Edge: B Cell-Intrinsic T-bet Expression Is Required To Control Chronic Viral Infection. J Immunol. 2016;197:1017–1022. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naradikian MS, Hao Y, Cancro MP. Age-associated B cells: key mediators of both protective and autoreactive humoral responses. Immunol Rev. 2016;269:118–129. doi: 10.1111/imr.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hao Y, O’Neill P, Naradikian MS, Scholz JL, Cancro MP. A B-cell subset uniquely responsive to innate stimuli accumulates in aged mice. Blood. 2011;118:1294–1304. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubtsov AV, Rubtsova K, Fischer A, et al. Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7)-driven accumulation of a novel CD11c(+) B-cell population is important for the development of autoimmunity. Blood. 2011;118:1305–1315. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-331462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moir S, Fauci AS. Pathogenic mechanisms of B-lymphocyte dysfunction in HIV disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.034. quiz 20–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rakhmanov M, Keller B, Gutenberger S, et al. Circulating CD21low B cells in common variable immunodeficiency resemble tissue homing, innate-like B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13451–13456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901984106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliviero B, Cerino A, Varchetta S, et al. Enhanced B-cell differentiation and reduced proliferative capacity in chronic hepatitis C and chronic hepatitis B virus infections. J Hepatol. 2011;55:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charles ED, Brunetti C, Marukian S, et al. Clonal B cells in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia contain an expanded anergic CD21low B-cell subset. Blood. 2011;117:5425–5437. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-312942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doi H, Tanoue S, Kaplan DE. Peripheral CD27-CD21-B-cells represent an exhausted lymphocyte population in hepatitis C cirrhosis. Clin Immunol. 2014;150:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Borrego F, Nagata S, Tolnay M. Fc Receptor-like 5 Expression Distinguishes Two Distinct Subsets of Human Circulating Tissue-like Memory B Cells. J Immunol. 2016;196:4064–4074. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damdinsuren B, Dement-Brown J, Li H, Tolnay M. B cell receptor induced Fc receptor-like 5 expression is mediated by multiple signaling pathways converging on NF-kappaB and NFAT. Mol Immunol. 2016;73:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terrier B, Nagata S, Ise T, et al. CD21(−/low) marginal zone B cells highly express Fc receptor-like 5 protein and are killed by anti-Fc receptor-like 5 immunotoxins in hepatitis C virus-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:433–443. doi: 10.1002/art.38222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan RT, Kim CC, Fontana MF, et al. FCRL5 Delineates Functionally Impaired Memory B Cells Associated with Plasmodium falciparum Exposure. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004894. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurktschiev PD, Raziorrouh B, Schraut W, et al. Dysfunctional CD8+ T cells in hepatitis B and C are characterized by a lack of antigen-specific T-bet induction. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2047–2059. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Hahn T, Yoon JC, Alter H, et al. Hepatitis C virus continuously escapes from neutralizing antibody and T-cell responses during chronic infection in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:667–678. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu M, Kruppenbacher J, Roggendorf M. The importance of the quasispecies nature of hepatitis C virus (HCV) for the evolution of HCV populations in patients: study on a single source outbreak of HCV infection. Arch Virol. 2000;145:2201–2210. doi: 10.1007/s007050070050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt-Martin D, Crosbie O, Kenny-Walsh E, Fanning LJ. Intensive temporal mapping of hepatitis C hypervariable region 1 quasispecies provides novel insights into hepatitis C virus evolution in chronic infection. J Gen Virol. 2015;96:2145–2156. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]