Abstract

Despite the high first line cure rates in patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) still 10–20% of patients suffer from relapsed or refractory disease. High dose chemotherapy (HDCT) followed by autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is standard of care for suitable patients with relapsed or refractory HL and allows for cure in approximately 50%. Due to the poor prognosis of high risk patients even with HDCT and ASCT, consolidation strategies have been evaluated to improve the cure rates. For patients with recurrence after HDCT and ASCT, treatment is palliative in most cases. The anti CD30 antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin (BV) has been shown to induce high response rates in these patients; however, durable responses were reported in a small percentage of patients only. For carefully selected patients with multiple relapses, dose-reduced allogeneic transplant (RICallo) is a potentially curative option. The role of RICallo will have to be reevaluated in the era of anti-programmed death-1 (PD1) antibodies.

Introduction

More than 80% of patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) achieve long-term cure with current polychemotherapies and additional radiotherapy where indicated (1–4). Even approximately 50% of patients with relapsed or refractory disease after first line therapy can be cured with high dose chemotherapy (HDCT) and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) followed by optional consolidation in high risk patients (5–7). After post-ASCT recurrence the antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) brentuximab vedotin (BV) has shown high efficacy and good tolerability (8); however, long-term remissions ware observed in a small percentage of patients only. New combinations of BV with established drugs are currently being evaluated to further improve the outcome of patients with relapsed or refractory HL. This article summarizes the current standard of care and emerging data in the management of relapsed or refractory classical HL in patients eligible for HDCT and ASCT. The management of other subgroups and new drugs are discussed separately in this issue.

Standard of care in first relapsed and refractory HL

High dose chemotherapy (HDCT) - evidence from randomized trials

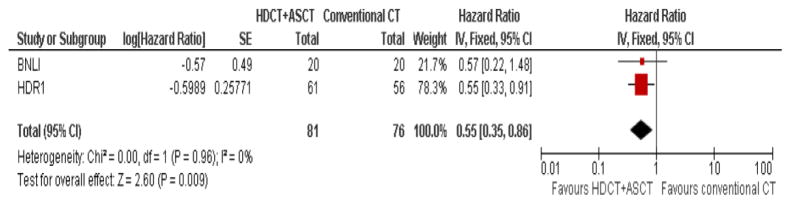

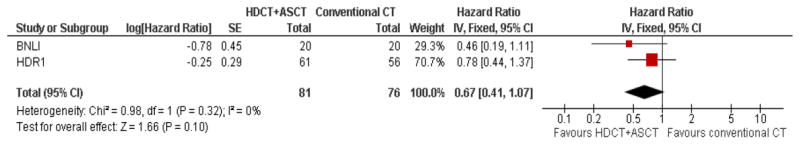

Because results with conventional chemotherapy were disappointing in patients with first relapsed or refractory HL, HDCT followed by ASCT was evaluated in this setting. Two prospective, randomized trials have defined the current standard of care in the treatment of relapsed and refractory HL (9, 10). The British National Lymphoma Investigation (BNLI) (9) trial randomized 40 patients who had not responded to first line chemotherapy to either conventional chemotherapy (mini-BEAM: 60 mg/m2 carmustine, 300 mg/m2 etoposide, 800 mg/m2 cytarabine, 30 mg/m2 melphalan q3wk for up to three cycles, standard group, 20 patients) or HDCT (BEAM: 300 mg/m2 carmustine, 800 mg/m2 etoposide, 1.600 mg/m2 cytarabine, 140 mg/m2 melphalan, experimental group, 20 patients) followed by ASCT support. The joint German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG)/European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) HD-R1 trial (10) randomized 161 patients with relapse after polychemotherapy to either HDCT plus ASCT (88 patients) or to conventional chemotherapy (73 patients). All patients in this trial received two cycles of Dexa-BEAM consisting of 240 mg dexamethasone, 60 mg/m2 carmustine, 1000 mg/m2 etoposide, 800 mg/m2 cytarabine and 20 mg/m2 melphalan. Chemosensitive patients were then randomized to either BEAM plus ASCT (300 mg/m2 carmustine, 1200 mg/m2 etoposide, 1600 mg/m2 cytarabine and 140 mg/m2 melphalan, 61 patients) or to two further cycles of Dexa-BEAM (56 patients), each after at least partial remission (PR) and hematologic recovery was shown through restaging. In both the BNLI and the HD-R1 trial patients with residual masses were allowed to receive radiotherapy which was performed in 17 and 11 patients in the BNLI and HD-R1 trial, respectively. Both trials showed a significant superiority of HDCT in terms of event-free survival (EFS)/freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) but failed to show a significant overall survival (OS) benefit. Three year rates were 53% versus 10% (EFS, p=0.005) in the BNLI and 55% versus 34% (FFTF, p=0.019) in the HD-R1 trial. Recently, a meta-analysis of the two trials using updated follow-up information was performed by the Cochrane Group for Hematological Malignancies (CHMG) (11). With a median follow-up of 34 and 83 months for BNLI and HD-R1, respectively, progression free survival (PFS) was significantly improved in patients who were treated with HDCT plus ASCT compared to those treated with conventional chemotherapy (hazard ratio [HR] 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.35–0.86, p = 0.009, Figure 1). However, the available evidence from the two trials was not sufficiently powered to show a statistically significant difference between HDCT plus ASCT and conventional chemotherapy in terms of OS (HR 0.67; 95%CI 0.41–1.07, p = 0.1, Figure 2). Nevertheless, the tendency towards an OS benefit of HDCT plus ASCT is considerable and the absence of a statistically significant OS benefit is most likely due to the small patient number in the two trials. Moreover, supportive care in patients receiving HDCT and ASCT has improved in the last years which presumably further increases the advantage of HDCT over conventional therapy. HDCT is widely accepted as standard of care in first relapsed and refractory HL.

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of trials comparing conventional chemotherapy (CT) with high dose chemotherapy (HDCT) followed by autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) in relapsed Hodgkin Lymphoma: Forest plot of comparison of progression-free survival (PFS).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of trials comparing conventional chemotherapy (CT) with high dose chemotherapy (HDCT) followed by autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) in relapsed Hodgkin Lymphoma: Forest plot of comparison of overall survival (OS).

Salvage chemotherapy

Conventional reinduction chemotherapy, often referred to as salvage therapy, is standard of care before administration of HDCT. It allows for a tumor reduction before ASCT and several reports have shown that the response to salvage therapy before ASCT is predictive for the final outcome (12, 13). From a straight evidence-based point of view, Dexa-BEAM should be the standard salvage regimen because it was used in the randomized HD-R1 trial that established HDCT as standard of care in relapse or refractory HL (10). However, Dexa-BEAM is hardly used today because it has a relatively high treatment related mortality (TRM) as compared to newer salvage combinations and is stem cell toxic leading to an inadequate stem cell harvest in many cases (14, 15). Owing to the lack of prospective, randomized trials comparing different salvage regimens the optimal choice of a salvage regimen is unclear. The ICE (5 g/m2 ifosfamide, area under the curve [AUC] 5 carboplatin, 300 mg/m2 etoposide) chemotherapy regimen which is regularly administered as an inpatient treatment for two cycles has become the standard salvage used in the US (16). In prospective clinical trials the complete response (CR) rate was approximately 50% and the overall response rate (ORR) was approximately 80%. For patients with unfavorable risk factors an augmented dosing has been evaluated (10 g/m2 ifosfamide, AUC 5 carboplatin, 600 mg/m2 etoposide) (16). Cytarabine-based regimens such as DHAP (160 mg dexamethasone, 4000 mg/m2 high dose ara-C [=cytarabine], 100 mg/m2 cisplatin) and ESHAP (160mg/m2 etoposide, 2000 mg methylprednisolone, 2000 mg/m2 high dose ara-C [=cytarabine], 100 mg/m2 cisplatin) have demonstrated similar response rates as compared to ICE (17, 18). The GHSG and other European cooperative groups regard DHAP as standard salvage regimen. The optimal cycle length of platin-based salvage chemotherapies has not been analyzed in prospective trials, however, a recent retrospective analysis of the GHSG showed that dose density of DHAP induction therapy is an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS in relapsed HL (19). Therefore, salvage chemotherapy should be administered in a dose dense way, where possible.

In the large randomized HD-R2 trial with 241 patients with relapsed HL, sequential high dose chemotherapy (SHDCT) after DHAP before BEAM was compared to conventional DHAP plus BEAM (20). However, FFTF and OS were not different in the two groups whereas patients treated with SHDCT had longer treatment duration and experienced more toxicity. Therefore, SHDCT before HDCT and ASCT is not a suitable strategy in patients with relapsed HL.

Gemcitabine-based chemotherapy regimens have been evaluated as alternative salvage regimens. The advantages of gemcitabine-based regimens are good tolerability and easier outpatient administration. GVD (2000 mg/m2 gemcitabine, 40 mg/m2 vinorelbine, and 30 mg/m2 pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in transplant naïve patients) was evaluated in 91 patients with relapsed or refractory HL and ORR was 70%, albeit with a modest 19% CR rate based upon CT imaging (21). Another program, IGEV (8000 mg/m2 ifosfamide, 400mg prednisolone, 1600 mg/m2 gemcitabine, and 20 mg/m2 vinorelbine) was administered to 91 patients of which 49 (54%) achieved a CR and 25 patients (27.5%) had a PR for an ORR of 81.3%, based upon PET imaging (22). Lastly, Kuruvilla et al retrospectively compared GDP (2000 mg/m2 gemcitabine, 40mg dexamethasone, and 75 mg/m2 cisplatin) with mini-BEAM; response rates were similar but GDP was far less toxic (23).

Brentuximab vedotin (BV) as salvage strategy

Recently, four studies have incorporated BV either sequentially or in combination with chemotherapy as part of a salvage strategy prior to ASCT (24–27). BV comprises an anti-CD30 antibody conjugated by a protease-cleavable linker to a microtubule-disrupting agent, monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE). BV demonstrated substantial efficacy, including an objective response rate of 75% and complete remission (CR) rate of 34%, in a pivotal phase two study of patients with CD30-positive HL who had failed HDCT and ASCT therapy and is approved in this setting (8). As a targeted therapy with minimal hematologic toxicity, BV may provide a unique opportunity to deliver therapy pre-ASCT.

Two studies, both peer reviewed and published, confirm a single agent response rate of > 80% as first salvage treatment, however the complete response rate is <40% (24, 25). Sequential treatment with platinum-based salvage treatment to patients lacking a PET negative response increases the CR rate to >80%. Three smaller studies have combined BV with either bendamustine, ICE or ESHAP and preliminary data suggests that the PET negative response is 75–90% (26, 27). Interestingly, patients achieving a CR to either single agent BV, sequential BV and chemotherapy or concomitant BV and chemotherapy all have similar two year PFS data post-ASCT: >80% of patients are progression-free. Clearly, single BV therapy will have the least side effects, but the lowest CR rate and likely prognostic factor analyses should determine the optimal salvage program.

In summary, several reasonable salvage options were evaluated in prospective non-randomized clinical trials and the clinician is left to choose based on the characteristics of the individual patient, personal experience, availability of drugs and the standards of a specific center.

Interim 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) during treatment for relapsed/refractory HL

As previously stated the current standard second-line treatment for relapsed or primary refractory HL is a multistep process that includes salvage chemotherapy, typically platinum-based, followed by HDCT and ASCT for patients with chemosensitive disease. Approximately 45–55% of the transplanted patients are cured (5–7). Long term PFS is dependent upon prognostic factors determined prior to salvage chemotherapy (20, 28, 29), but more importantly, response to this chemotherapy whether complete or partial is the focal point in predicting outcome.

A number of years ago, we and others, determined that chemosensitive disease should be defined by the pre-transplant PET result (30). A negative scan after platinum-based therapy leads to a 5 year PFS rate of 75%. For patients with documented improvement on CT, but with a persistent PET-avidity, only 30% are cured. It is very clear that a post-salvage chemotherapy PET scan is an interim evaluation, since definition of remission status is assessed at 90–100 days post-ASCT. Reporting should then be similar to that of untreated HL, scores 1–3 based upon Deauville or five point criteria are negative and 4 and 5 are positive. Investigators need to decide if patients with an abnormal, but chemosensitive scan, require a second attempt to achieve a CR, to improve upon a suboptimal 30% cure rate (31). Another option in this setting could be to adjust transplant-regimens or administer post-transplant therapy (32, 33).

Complicating that matter further, not all patients with a PET negative post-salvage chemotherapy response are equally curable. As discussed in this manuscript outcome for patients with nodal only disease is superior to that of patients with stage IV or non-contiguous extranodal involvement. For example patients with nodal only disease in remission at the time of ASCT have 90%cure rate compared to 67% for patients with extranodal disease. These results clearly have impact on the need or lack thereof for post-ASCT consolidative treatment. Lastly, as was discussed on the BV section, there is no difference in outcome comparing patients achieving a PET negative response with inpatient multiagent salvage chemotherapy compared to a simple outpatient approach.

Consolidation after high dose chemotherapy (HDCT)

Risk factors in HL patients receiving HDCT

It has been shown in several analyses that patients with certain adverse prognostic factors at recurrence have a poor prognosis even with HDCT (see also chapter 3 “Prognostic factors in Hodgkin Lymphoma” in this issue) (20, 28, 29). Especially the prognosis of patients with primary refractory disease is dismal with previously reported 5-year OS rates of 30% or less. Other factors that have been found to be associated with an inferior outcome are stage III/IV, extranodal disease, B-symptoms, anemia, poor performance status and bulky disease at relapse as well as early first relapse (< 12 months), in-field relapse after radiotherapy and non-response to salvage (14). Consolidation after HDCT has been evaluated in order to improve the results in patients with high risk disease.

Tandem autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT)

In the prospective Société Francaise de Greffe de Moelle (SFGM) and Groupe d’Étude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) H96 trial 150 high risk patients (primary refractory disease [n=77] or ≥2 of the following risk factors at first relapse: early relapse, stage III or IV at relapse, in-field relapse after radiotherapy [n=73]) and 95 intermediate risk patients (one risk factor at relapse) received tandem or single HDCT plus ASCT, respectively (6). The results of the recently published long-term follow-up of this trial compare favorably to historical data: with a median follow-up of 10.3 years, median FFTF and OS were 64% (95% CI, 54% to 74%) and 70% (95% CI, 61% to 80%) for the intermediate-risk group, and 41% (95% CI, 33% to 49%) and 47% (95% CI, 39% to 55%), for the poor-risk group (34). Three other analyses also suggested a benefit of a second ASCT as consolidation in high-risk relapsed/refractory HL patients (32, 35, 36); however, evidence from a randomized controlled trial comparing single versus tandem ASCT in high risk patients is lacking.

Post-transplant maintenance strategy

There is one recent study addressing the issue of post-transplant consolidative therapy, the AETHERA trial (33). Patients had primary-refractory or relapsed HL and were treated with BV or placebo starting 30–45 days after HDCT and ASCT. The objective of the study was to compare PFS between the two treatment arms. The study achieved its primary objective, demonstrating a significant PFS benefit for patients in the BV arm versus placebo (HR = 0.52, p = 0.001). Based upon investigator review there is an 18% improvement in PFS at three years post-ASCT (Figure 3) (37). There is no difference in OS at this time point, which is almost certainly due to the availability BV for the placebo patients that progressed; these patients were enrolled on a companion protocol to receive BV free of charge. In this randomized, placebo-controlled study of HL patients with pre-salvage risk factors for progression, remission duration < 1 year, primary refractory disease or extranodal disease, were eligible to receive consolidative treatment with BV provided a statistically and clinically significant improvement in PFS per independent review facility (IRF) and per investigator, compared to placebo. In multivariate analysis besides three risk factors just stated B symptoms at salvage, less than a CR to salvage therapy or needing > 1 salvage regimen to achieve chemosensitive disease predicted for outcome. Greater than 50% of patients on study had at least three risk factors and in this cohort patients receiving BV had a three year PFS of 60% versus only 30% for patients receiving placebo (Figure 4). Only 2/3 of patients had a PET scan pre-ASCT since this test was not required, however in an ad hoc analysis it appears that if complete response was evident, only patients that had two or more risk factors benefited from consolidation; this will need to be confirmed in subsequent studies. Clinical trials are underway evaluating checkpoint inhibitors as consolidation post-ASCT.

Figure 3.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial of brentuximab vedotin (BV) as consolidation therapy after autologous stem cell transplant in patients with high risk Hodgkin Lymphoma (AETHERA): Progression-free survival (PFS) per investigator 3 years since last patient randomized. Includes clinical assessments of lymphoma.

Figure 4.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial of brentuximab vedotin (BV) as consolidation therapy after autologous stem cell transplant in patients with high risk Hodgkin Lymphoma (AETHERA): Risk factors associated with poor outcomes.

Standard of care in patients with recurrence after ASCT

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy

Treatment of patients with recurrence after ASCT is palliative in most cases. Several trials have evaluated conventional chemotherapy in this setting and single agents as well as combinations of cytotoxic drugs have shown activity in multiple relapsed HL. Gemcitabine, vinorelbine, bendamustine and GVD are some of the potential options (21, 38–40). However, long-term remissions are very uncommon with conventional chemotherapy and approximately 70–80% of patients died within the first five years after post-ASCT relapse according to analyses from the pre-BV era (41, 42). Radiotherapy has been shown to induce durable remissions in selected patients with localized relapse and should be considered where possible (43).

Brentuximab vedotin (BV)

In August 2011, the anti-CD30 ADC BV was the first pharmacotherapy for the treatment of patients with HL approved by the US food and drug administration (FDA) since approximately 30 years (44). In a pivotal phase II prospective trial with 102 patients with relapsed HL after HDCT and ASCT BV as single agent (1.8 mg/kg q3wk) induced a high ORR of 75% and a CR rate of 34% (8). Of note, 71% of patients in the trial had disease refractory to prior treatments which underlines the high single agent activity of BV. Overall, BV was well tolerated; the most common grade 3 or grade 4 adverse events (AEs) were peripheral sensory neuropathy (8%), fatigue (2%), neutropenia (20%) and diarrhea (1%). In the recently presented 5-year follow-up of the trial (45), the median overall survival (OS) was 40.5 months (95% CI: 28.7, 61.9 [range, 1.8 – 72.9+ months]) and the estimated 5-year survival rate was 41% (95% CI: 31, 51%). At a median of 35.1 months (range, 1.8 – 72.9 months) since first dose of BV, the median PFS was 9.3 months overall, but was not reached in CR patients. At the time of presentation, 15 patients remained in remission and were still being followed at study closure; of the 15 patients, 6 received consolidative allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloSCT) and 9 have had no treatment following BV. These data suggest that a small proportion of patients might be cured with BV even after post-ASCT relapse.

Allogeneic transplant (alloSCT) in Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) patients with recurrence after autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT)

In most centers, alloSCT is exclusively performed in patients with HL recurrence after ASCT and even at relapse after ASCT, alloSCT is an option for carefully selected patients only. The reduced relapse rate associated with a potential graft-versus-tumor effect is offset by lethal graft-versus-host toxicity. Data on alloSCT in HL are limited to phase II or retrospective studies, randomized trials are lacking. Myeloablative conditioning in HL led to poor results because of the exceedingly high non-relapse mortality (46); however, several analyses showed that dose-reduced allogeneic transplant (RIC-alloSCT) might be an option for patients relapsing after ASCT (47, 48). The largest prospective trial with RIC-alloSCT in relapsed or refractory HL was performed by the Grupo Español de Linfomas/Trasplante de Médula Osea (GEL/TAMO) and the Lymphoma Working Party of the EBMT (49). In this phase II study, 92 patients were planned to receive salvage therapy followed by RIC-alloSCT (conditioning regimen: fludarabine 150 mg/m2, melphalan 140 mg/m2). Of those, 79 had prior ASCT and 78 patients proceeded to RIC-alloSCT. Anti-thymocyte globulin was additionally used as graft-versus-host-disease prophylaxis for recipients of grafts from unrelated donors (23 patients). The PFS rate was 47% and 18% at 1 and 4 years from trial entry, respectively. For the allografted population, the PFS rate was 48% and 24% at 1 and 4 years, respectively, and the OS rate was 71% and 43% at 1 and 4 years, respectively. Patients allografted in CR had a significantly better outcome. In summary, RIC-alloSCT is an option for selected HL patients with post-ASCT relapse achieving a remission to salvage chemotherapy. Recent data also suggest that haploidentical alloSCT may be an effective approach for cHL patients with relapse after ASCT (50, 51). Lately, BV was evaluated as potential salvage therapy prior alloSCT and several retrospective reports yielded promising results (52, 53). The role of alloSCT in HL will have to be reevaluated in the era of programmed death 1 (PD-1) checkpoint inhibitors that will be reviewed separately in this issue.

Acknowledgments

CM has received research support from Merck and Seattle Genetics.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

BvT has received honoraria for consultancy, reimbursement of congress, travel, and accommodation costs and honoraria for preparation of scientific educational events from Takeda.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Bastian von Tresckow, German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG), University Hospital of Cologne, Kerpener Str. 62, 50937 Cologne, Telephone: +49 221 478-97657.

Craig Moskowitz, Clinical Director, Division of Hematologic Oncology, Member, Lymphoma and Transplant Services, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Professor of Medicine, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, Telephone: +1 212-639-2696.

References

- 1.Engert A, Plutschow A, Eich HT, et al. Reduced treatment intensity in patients with early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 12;363(7):640–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Tresckow B, Plutschow A, Fuchs M, et al. Dose-intensification in early unfavorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma: final analysis of the German hodgkin study group HD14 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Mar 20;30(9):907–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engert A, Haverkamp H, Kobe C, et al. Reduced-intensity chemotherapy and PET-guided radiotherapy in patients with advanced stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HD15 trial): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012 May 12;379(9828):1791–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon LI, Hong F, Fisher RI, et al. Randomized phase III trial of ABVD versus Stanford V with or without radiation therapy in locally extensive and advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: an intergroup study coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (E2496) J Clin Oncol. 2013 Feb 20;31(6):684–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Tresckow B, Engert A. The role of autologous transplantation in Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2011 Sep;6(3):172–9. doi: 10.1007/s11899-011-0091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morschhauser F, Brice P, Ferme C, et al. Risk-adapted salvage treatment with single or tandem autologous stem-cell transplantation for first relapse/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results of the prospective multicenter H96 trial by the GELA/SFGM study group. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Dec 20;26(36):5980–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moskowitz CH, Nadamanee A, Masszi T, et al. The Aethera Trial: Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Study of Brentuximab Vedotin in the Treatment of Patients at Risk of Progression Following Autologous Stem Cell Transplant for Hodgkin Lymphoma. Abstract presented at Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Blood; 2014-12-06 00:00:00; 2014. p. 673. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a Pivotal Phase II Study of Brentuximab Vedotin for Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Jun 20;30(18):2183–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linch DC, Winfield D, Goldstone AH, et al. Dose intensification with autologous bone-marrow transplantation in relapsed and resistant Hodgkin’s disease: results of a BNLI randomised trial. Lancet. 1993 Apr 24;341(8852):1051–4. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92411-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitz N, Pfistner B, Sextro M, et al. Aggressive conventional chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed chemosensitive Hodgkin’s disease: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002 Jun 15;359(9323):2065–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08938-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rancea M, Monsef I, von Tresckow B, Engert A, Skoetz N. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013;6:CD009411. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009411.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brice P, Bouabdallah R, Moreau P, et al. Prognostic factors for survival after high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with relapsing Hodgkin’s disease: analysis of 280 patients from the French registry. Societe Francaise de Greffe de Moelle. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997 Jul;20(1):21–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sureda A, Constans M, Iriondo A, et al. Prognostic factors affecting long-term outcome after stem cell transplantation in Hodgkin’s lymphoma autografted after a first relapse. Ann Oncol. 2005 Apr;16(4):625–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Tresckow B, Moskowitz C. Relapsed and Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma. In: Engert A, Younes A, editors. Hodgkin Lymphoma. Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp. 321–30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moskowitz CH, Glassman JR, Wuest D, et al. Factors affecting mobilization of peripheral blood progenitor cells in patients with lymphoma. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 1998 Feb;4(2):311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moskowitz CH, Nimer SD, Zelenetz AD, et al. A 2-step comprehensive high-dose chemoradiotherapy second-line program for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin disease: analysis by intent to treat and development of a prognostic model. Blood. 2001 Feb 1;97(3):616–23. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Josting A, Rudolph C, Reiser M, et al. Time-intensified dexamethasone/cisplatin/cytarabine: an effective salvage therapy with low toxicity in patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol. 2002 Oct;13(10):1628–35. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aparicio J, Segura A, Garcera S, et al. ESHAP is an active regimen for relapsing Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol. 1999 May;10(5):593–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1026454831340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasse S, Alram M, Muller H, et al. Prognostic relevance of DHAP dose-density in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma: an analysis of the German Hodgkin-Study Group. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015 Dec;23:1–7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1083561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Josting A, Muller H, Borchmann P, et al. Dose intensity of chemotherapy in patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Dec 1;28(34):5074–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartlett NL, Niedzwiecki D, Johnson JL, et al. Gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (GVD), a salvage regimen in relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma: CALGB 59804. Ann Oncol. 2007 Jun;18(6):1071–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santoro A, Magagnoli M, Spina M, et al. Ifosfamide, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine: a new induction regimen for refractory and relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Haematologica. 2007 Jan;92(1):35–41. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuruvilla J, Nagy T, Pintilie M, Tsang R, Keating A, Crump M. Similar response rates and superior early progression-free survival with gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin salvage therapy compared with carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan salvage therapy prior to autologous stem cell transplantation for recurrent or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2006 Jan 15;106(2):353–60. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen R, Palmer JM, Martin P, et al. Results of a Multicenter Phase II Trial of Brentuximab Vedotin as Second-Line Therapy before Autologous Transplantation in Relapsed/Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015 Dec;21(12):2136–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moskowitz AJ, Schoder H, Yahalom J, et al. PET-adapted sequential salvage therapy with brentuximab vedotin followed by augmented ifosamide, carboplatin, and etoposide for patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a non-randomised, open-label, single-centre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015 Mar;16(3):284–92. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaCasce AS, Bociek G, Sawas A, et al. Brentuximab Vedotin Plus Bendamustine: A Highly Active Salvage Treatment Regimen for Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma. Blood 2015. 2015 Dec 03;126(23):3982. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-11-815183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Sanz R, Sureda A, Alonso-Alvarez S, et al. Evaluation of the Regimen Brentuximab Vedotin Plus ESHAP (BRESHAP) in Refractory or Relapsed Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients: Preliminary Results of a Phase I–II Trial from the Spanish Group of Lymphoma and Bone Marrow Transplantation (GELTAMO) Blood 2015. 2015 Dec 03;126(23):582. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Josting A, Franklin J, May M, et al. New prognostic score based on treatment outcome of patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma registered in the database of the German Hodgkin’s lymphoma study group. J Clin Oncol. 2002 Jan 1;20(1):221–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bröckelmann PJ, Müller H, Casasnovas O, et al. Risk Factors and a Prognostic Score for Progression Free Survival after Treatment with Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation (ASCT) in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma (rrHL) Blood 2015. 2015 Dec 03;126(23):1978. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moskowitz AJ, Yahalom J, Kewalramani T, et al. Pretransplantation functional imaging predicts outcome following autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2010 Dec 2;116(23):4934–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moskowitz CH, Matasar MJ, Zelenetz AD, et al. Normalization of pre-ASCT, FDG-PET imaging with second-line, non-cross-resistant, chemotherapy programs improves event-free survival in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2012 Feb 16;119(7):1665–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-388058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devillier R, Coso D, Castagna L, et al. Positron emission tomography response at time of autologous stem cell transplantation predict outcome of patients with relapsed and/or refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma responding to prior salvage therapy. Haematologica. 2012 Jan 22; doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.056051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moskowitz CH, Nademanee A, Masszi T, et al. Brentuximab vedotin as consolidation therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at risk of relapse or progression (AETHERA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015 Mar 18; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sibon D, Morschhauser F, Resche-Rigon M, et al. Single or tandem autologous stem-cell transplantation for first-relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: 10-year follow-up of the prospective H96 trial by the LYSA/SFGM-TC study group. Haematologica. 2015 Dec 31; doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.136408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fung HC, Stiff P, Schriber J, et al. Tandem autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with primary refractory or poor risk recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007 May;13(5):594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moskowitz CH, Yahalom J, Zelenetz AD, et al. High-dose chemo-radiotherapy for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma and the significance of pre-transplant functional imaging. Br J Haematol. 2010 Mar;148(6):890–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sweetenham J, Walewski J, Nademanee AP, et al. Updated Efficacy and Safety Data from the AETHERA Trial of Consolidation with Brentuximab Vedotin after Autologous Stem Cell Transplant (ASCT) in Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients at High Risk of Relapse. Blood 2015. 2015 Dec 03;126(23):3172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santoro A, Bredenfeld H, Devizzi L, et al. Gemcitabine in the treatment of refractory Hodgkin’s disease: results of a multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Jul;18(13):2615–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.13.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devizzi L, Santoro A, Bonfante V, et al. Vinorelbine: an active drug for the management of patients with heavily pretreated Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol. 1994 Nov;5(9):817–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moskowitz AJ, Hamlin PA, Jr, Perales MA, et al. Phase II study of bendamustine in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Feb 1;31(4):456–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Tresckow B, Muller H, Eichenauer DA, et al. Outcome and risk factors of Hodgkin Lymphoma patients who relapse or progress after autologous stem cell transplant. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013 Oct 21; doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.854888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez C, Canals C, Sarina B, et al. Identification of prognostic factors predicting outcome in Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients relapsing after autologous stem cell transplantation. Ann Oncol. 2013 May 26; doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Josting A, Nogova L, Franklin J, et al. Salvage radiotherapy in patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a retrospective analysis from the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Mar 1;23(7):1522–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Tresckow B, Diehl V. An update on emerging drugs for Hodgkin lymphoma. Expert opinion on emerging drugs. 2014 Jun;19(2):215–24. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2014.912277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen R, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Five-Year Survival Data Demonstrating Durable Responses from a Pivotal Phase 2 Study of Brentuximab Vedotin in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma. Blood 2015. 2015 Dec 03;126(23):2736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Milpied N, Fielding AK, Pearce RM, Ernst P, Goldstone AH. Allogeneic bone marrow transplant is not better than autologous transplant for patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s disease. European Group for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1996 Apr;14(4):1291–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.4.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sureda A, Robinson S, Canals C, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning compared with conventional allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an analysis from the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jan 20;26(3):455–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peggs KS, Hunter A, Chopra R, et al. Clinical evidence of a graft-versus-Hodgkin’s-lymphoma effect after reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation. Lancet. 2005 Jun 4–10;365(9475):1934–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66659-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sureda A, Canals C, Arranz R, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Results of the HDR-ALLO study - a prospective clinical trial by the Grupo Espanol de Linfomas/Trasplante de Medula Osea (GEL/TAMO) and the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2012 Feb;97(2):310–7. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.045757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burroughs LM, O’Donnell PV, Sandmaier BM, et al. Comparison of outcomes of HLA-matched related, unrelated, or HLA-haploidentical related hematopoietic cell transplantation following nonmyeloablative conditioning for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008 Nov;14(11):1279–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raiola A, Dominietto A, Varaldo R, et al. Unmanipulated haploidentical BMT following non-myeloablative conditioning and post-transplantation CY for advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014 Feb;49(2):190–4. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen R, Palmer JM, Thomas SH, et al. Brentuximab vedotin enables successful reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2012 Jun 28;119(26):6379–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-418673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garciaz S, Coso D, Peyrade F, et al. Brentuximab vedotin followed by allogeneic transplantation as salvage regimen in patients with relapsed and/or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hematological oncology. 2014 Dec;32(4):187–91. doi: 10.1002/hon.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]