Abstract

Objective

To determine the impact of the TEACH text message intervention as a pragmatic approach for patient engagement among adolescents with celiac disease (CD) as measured by gluten-free diet (GFD) adherence, patient activation, and quality of life (QOL).

Study design

Randomized controlled trial with patient recruitment at a pediatric, university-based hospital and through social media; 61 participants ages 12–24 with CD diagnosed at least one year were enrolled. The TEACH intervention cohort received 45 unique text messages over a 3 month study period while the control group received standard of care treatment. Primary outcome measures included objective markers of GFD adherence included serum Tissue Transglutaminase (TTG) IgA and Deamidated Gliadin Peptide (DGP) IgA levels. Secondary patient-reported outcomes collected via online survey included the Celiac Dietary Adherence Test (CDAT), NIH PROMIS Global Short Form measure of QOL, Celiac Symptom Index (CSI), and Patient Activation Measure (PAM). All measures were assessed at enrollment and after the three month study period. Statistical analysis performed using the two-tailed paired student t-test.

Results

Among the TEACH intervention group, there was significant improvement comparing enrollment scores with three month follow-up scores in patient activation (PAM score 63.1 vs 72.5, P=0.01) and QOL (NIH PROMIS Global Mental Health 50.8 vs 53.3, P=0.01 and NIH PROMIS Global Physical Health 50.8 vs 57.7, P=0.03). There was no statistically significant difference in patient-reported or objectively measured GFD adherence.

Conclusions

TEACH is an effective intervention among patients with CD to improve patient activation and QOL, even among a cohort with GFD adherence at baseline.

Trial Registration

Keywords: mobile health, patient reported outcomes, SMS

Celiac disease (CD) is an immune-mediated enteropathy caused by gluten ingestion that results in increased intestinal permeability and nutrient malabsorption. There are nearly three million people with CD in the United States, the majority of whom are undiagnosed or untreated, with an estimated prevalence of 3–13:1000 among the pediatric population(1–4). Uncontrolled CD can lead to poor quality of life (QOL) and morbidity, including infertility, non-traumatic fractures, and malignancy(1–4). The only treatment for CD at this time is strict elimination of gluten from the diet.

Although the management of CD is simple in theory, lifelong adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD) can be challenging. The adolescent and young adult population is at increased risk for poor adherence in the management of chronic illnesses(5–7). Barriers to adherence identified among patients with chronic disease include a desire for normality and freedom, poor physical or mental well-being, and lack of support from peers, parents, or healthcare providers(6). Adolescents with CD are more likely to be non-adherent to GFD compared with younger children or adults, particularly in social settings outside the home or when transitioning to college where they have greater independence in preparing meals and are more susceptible to peer pressure(8–11). Patients with non-adherence in the management of chronic disease are at risk for poor QOL, adverse health outcomes, and increased healthcare costs(7,12).

Studies among adults with CD show improvement in GFD adherence using online behavioral interventions(13), yet there is a paucity of research among the adolescent CD population to address GFD adherence. Growing evidence suggests that patients with chronic disease may adopt health-conscious co-management skills through online behavioral intervention or mobile technology such as text messaging(14–17). Text messaging is a familiar form of communication among adolescents; 91% of teens with a cell phone use text messaging to communicate with an average of 30 messages sent and received per day(18). Emerging adult(19–23) and pediatric(24–31) data from the current self-monitoring mobile health movement show that well-designed phone text messaging interventions reduce adverse health outcomes, improve adherence to therapy plans, increase patient activation, and improve overall QOL among patients with chronic disease. However, there are no studies showing similar utility of text messaging among adolescents or young adults with CD.

We hypothesize that our Text Message Educational Automated Compliance Help (TEACH) program may be a novel text message intervention to engage and educate adolescents and young adults with CD. Intended as an automated text messaging tool, we designed the components of TEACH to be a pragmatic way to improve GFD adherence, patient activation, and QOL among adolescents and young adults with CD. The primary objective of this study was to determine whether enrollment in TEACH will improve GFD adherence as measured by percent change in serum Tissue Transglutaminase (TTG) IgA and Deamidated Gliadin Peptide (DGP) IgA over the three month study period. The secondary objective was to determine TEACH’s impact on patient-reported GFD adherence, patient activation, disease symptomatology, and QOL.

METHODS

The TEACH Program study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02458898) is a block randomized controlled clinical trial among 61 patients ages 12–24 with CD. The study protocol and ethical considerations were approved by the Stanford Human Subjects Research and IRB board. Informed telephone consent was obtained from parents for children < 18 years of age with online assent or consent provided by study participants depending on age. Participant referral, consent, and data collection were performed through an integrated, secure Stanford REDCap database. After obtaining consent and child assent when indicated, participants were randomized into the TEACH intervention group receiving text messages or the control group with standard of care management by their primary gastroenterologist. The control group was aware of their enrollment in a text message reminder study through the informed consent process. All participants completed four surveys including the Celiac Dietary Adherence Test (CDAT), NIH PROMIS Global Short Form, Celiac Symptom Index (CSI), and Patient Activation Measure (PAM) online through the secure REDCap database upon enrollment and after completion of the 3 month study intervention period. Serum TTG IgA and DGP IgA were obtained at the time of enrollment and after the 3 month study intervention through Stanford or LabCorp laboratory. Total IgA levels were obtained with enrollment laboratories to evaluate for IgA deficiency.

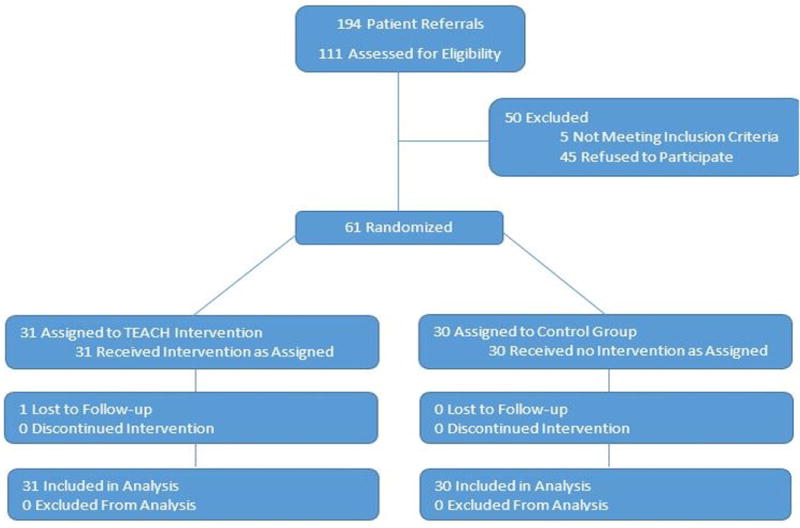

Participants were referred from Stanford Children’s Health network, Oakland Children’s Hospital, or through online social media recruitment from across the United States using our REDCap patient referral website and were screened for eligibility by the principle investigator over the phone. Enrollment criteria included age 12–24, CD diagnosed at least one year prior to study enrollment, access to a mobile phone and email, and the ability to read English. Sixty-one participants were enrolled of 194 participant referrals (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com).

Figure 1.

Study Recruitment and Enrollment Algorithm

Block randomization was performed based on enrollment TTG IgA level (< 4, 4–10, or > 10). Randomization algorithm was generated by coin flip and was integrated into the REDCap database programming to occur once consent and baseline outcome measures were obtained by study coordinator.

TEACH intervention was comprised of 45 unique messages developed by our study team and CD dietician (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com). Automated text messages were sent to the TEACH intervention cohort two to three times per week in the evenings over the three month study period via Twilio interface with REDCap study website. Text message content included fifteen links to online resources such as gluten-free recipes, restaurant search tools, or CD organization websites, 15 humorous reminders to stay gluten-free, and 15 bidirectional quiz questions. A complete list of text messages sent to participants is shown in Table I.

Table 1.

TEACH Program Text Message Content

| Going out to dinner? Check out this restaurant search tool to identify a gluten free option near you www.glutenfreerestaurants.org |

| Time for dinner? Fajitas or quesadillas with corn tortillas, chicken, cheese, or beef are tasty and gluten free. |

| What is gluten? [A]Preservative, [B] Type of sugar, [C] Flavoring, [D] Naturally occurring protein. Text back with your guess! (A, B, C, D) |

| What did one toilet say to the other toilet? You look flushed. Keep up to good work with your gluten free diet today. |

| The Celiac Support Association website www.csaceliacs.info has a gluten free restaurant search tool. Enjoy a dinner out on the town! |

| Be a celiac disease advocate! Check out national organizations like Gluten Intolerance group www.gluten.net or Celiac Disease Foundation www.celiac.org |

| [T]rue or [F]alse: Items such as mouthwash, lipstick, and medications never contain gluten. Text back with your guess! (T or F) |

| How do you make an egg-roll? You push it! Remember to eat gluten free foods today, like eggs. |

| Planning a trip? The Celiac Support Association has a travel resource page with information on planning a gluten free vacation glutenfreeresourcedirectory.com |

| Snack time! Vegetables or gluten free rice cakes with hummus are nutritious and gluten free. |

| Questions about celiac disease? Check out the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology website www.gikids.org/content/3/en/Celiac-Disease |

| What do you do when you cross a cheetah and a hamburger? Fast food! Keep up the good work with your gluten free diet today. |

| [Y]es or [N]o: Do you find it’s challenging to stay gluten free when going out to eat with friends? Text back with your response! (Y or N) |

| Feeling adventurous? Try one of these exciting gluten free recipes www.foodandwine.com/slideshows/gluten-free |

| Interested in summer camp or being a camp counselor? The Celiac Support Association www.csaceliacs.info/camps.jsp has information on celiac disease camps. |

| Which cooking ingredient often contains gluten: [A] Vanilla, [B] Soy Sauce, [C] Butter, [D] Molasses. Text back with your guess! (A, B, C, D) |

| Which of these supposedly gluten free foods often contains gluten: [A] Ketchup, [B] Mustard, [C] Malt vinegar, [D] Pepper? Text back with your guess! (A,B,C,D) |

| Hungry? Many major brands now offer pre-packaged gluten free pie, pizza, and cookie dough. |

| How do you stop a charging rhino? You take away his credit card. Keep “charging” along with your gluten free diet. |

| [Y]es or [N]o: Have you had any abdominal pain in the past week? Text back with your response! (Y or N) |

| Why don’t they play poker in the jungle? Too many cheetahs! Don’t be a “cheetah” and remember to keep up the good work with your gluten-free diet today. |

| [T]rue or [F]alse: Sharing a toaster used for regular bread is nothing to worry about for people with celiac disease. Text back with your guess! (T or F) |

| What do you call cheese that doesn’t belong to you? Nacho cheese! Remember to stay gluten free today—maybe with corn chips and gluten free nacho cheese. |

| Why did the math book look so sad? Because he had a lot of problems. We know you’ll have no problem remembering to stay gluten free today! |

| [T]rue or [F]alse in your experience: most of my friends know that I have celiac disease. Text back with your response! (T or F) |

| [Y]es or [N]o: Do you have friends with celiac disease? Text back with your response! (Y or N) |

| Fresh fruits and vegetables are tasty, gluten free, and nutritious! Find your favorite at a local farmer’s market or grocery store. |

| [T]rue or [F]alse: About one in every one hundred children and adolescents in the United States has celiac disease. Text back with your guess! (T or F) |

| Most grocery stores have gluten free pizza in the frozen food aisle if you are hungry for a quick meal. |

| Which of the following is a gluten-free grain or flour: [A] Risotto, [B] Barley, [C] couscous, or [D] Bulgar? Text back with your guess! (A, B, C, or D) |

| What did the baby corn say to the mama corn? Where’s pop corn? Keep up the good work with your gluten free diet such as popcorn! |

| What do you call a fake noodle? An impasta! Keep up the great work with your gluten free diet, and stay away from gluten impostors! |

| Calcium is important for growing bones. String cheese, cottage cheese, milk, and most yogurts are delicious sources of gluten free calcium. |

| [Y]es or [N]o: Does anyone else in your family follow a gluten free diet? Text back with your response! (Y or N) |

| [T]rue or [F]alse in your experience: it is easy for me to stay gluten free when I prepare my own meals. Text back with your response! (T or F) |

| Consider finding a gluten free bakery in your area and enjoy a macaroon or other gluten free treat. |

| Two snowmen are talking in the yard when one says “say, do you smell carrots?” Remember to stay gluten free today, maybe have a carrot for a snack! |

| What kind of shoes to baby cowboys wear? Cowbooties! Have a great day, and remember to stay gluten free. |

| Two silk worms were in a race…what was the result? A tie. Keep up the good work with your gluten free diet and you will be racing towards success. |

| What do you call a seagull that flies over the bay? A bagel! Great job staying gluten free today. |

| What’s black, white, black, white, black, white? A penguin rolling down a hill. You’re on a roll with your gluten free diet today! |

| What do you call a fly with no wings? A walk. Remember to stay on track with your gluten free diet today! |

| [T]rue or [F]alse in your experience: I have a favorite restaurant that offers gluten free foods. Text back with your response! (T or F) |

| Going to the movies? Popcorn is a delicious gluten free snack, but some buttery toppings can contain gluten. |

| [T]rue or [F]alse: It is safe to cook gluten free pancakes on the same pan as regular pancakes? Text back with your guess! (T or F) |

Demographic information was obtained upon enrollment (Table II). Participants completed four validated patient-reported survey outcome measures (CDAT, NIH PROMIS Global Short Form, CSI, and PAM) at enrollment and after the three month study period. The CDAT is a measure of GFD adherence validated among adults(32), though it has been used in a research setting among patients age 16 and above(13). It is composed of seven questions with scores ranging from 7–35; scores, < 13 indicate good GFD adherence(32). The NIH PROMIS Global Short Form is a ten question measure of QOL validated among adults 18 year of age and above with physical and mental health components; higher scores indicate better QOL(33). The CSI is a 16 question measure of CD activity validated among adults 18 years of age and above with scores ranging from 16–80; scores < 30 indicate good disease control and scores > 45 indicate poor disease control(34). PAM is a 13 item measure of patient activation validated among adults age 18 and above, though it has been used in a research setting among patients as young as 12 years of age(35). Scores range from 0–100; higher scores indicate greater patient activation with an improvement by four points thought to be clinically meaningful(36). Objective serum markers (TTG IgA and DGP IgA) were obtained at enrollment and after the three month study period through Stanford or LabCorp. The same laboratory system was used for enrollment and follow-up labs for each participant. Logs of text messages sent and participant responses were collected via REDCap study website, and anonymous participant feedback was obtained upon study completion.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics at Time of Enrollment based on Randomization to TEACH Intervention or Control Group

| Clinical Values | TEACH Intervention (n=31) Number (%) |

Control (n=30) Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 15 (48) | 4 (13) |

| Female | 16 (52) | 26 (87) |

| Mean Age (years) | 15.8±2.4 | 16.4±3.4 |

| Grade in School | ||

| 6th–8th Grade | 8 (26) | 9 (30) |

| 9th–12th Grade | 16 (52) | 12 (40) |

| 2 year or 4 year College | 6 (19) | 4 (13) |

| Not currently in school | 1 (3) | 5 (17) |

| Living Situation | ||

| Living at home with family | 26 (84) | 27 (90) |

| Living in dorm or apartment with friends or roommates | 4 (13) | 3 (10) |

| Living in dorm or apartment alone | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Years Since Diagnosis | ||

| 1 year | 5 (16) | 3 (10) |

| 2–5 years | 11 (35) | 12 (40) |

| 6–10 years | 9 (29) | 12 (40) |

| >10 years | 6 (19) | 3 (10) |

| Number of meals prepared outside the home per week | ||

| None | 3 (10) | 1 (3) |

| 1–4 | 24 (77) | 23 (77) |

| 5–10 | 1 (3) | 5 (17) |

| 10–15 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 15–20 | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Every meal or nearly every meal | 2 (7) | 1 (3) |

Statistical Analyss

A two-tailed paired student t-test was used to compare the percent change in TTG IgA and DGP IgA from enrollment with three month follow-up levels in the TEACH intervention group compared with the control group. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was also used to compare mean scores for patient-reported survey outcomes at enrollment and upon study completion among the TEACH intervention group and the control group. Analysis followed intent-to-treat principles.

Results

Sixty-one participants were enrolled from March 2015 to November 2015, with data collection through February 2016; 30 participants were randomized to the control group and 31 participants to the TEACH group. As depicted in Figure 1, all participants were analyzed in the group to which they were originally randomized; one participant from the TEACH group was lost to follow-up. The five participants who did not meet inclusion criteria had been diagnosed with CD for less than one year.

Table II shows demographic information at the time of enrollment. Despite randomization there were more females in the control group. Of note, the majority of study participants were already adherent to a GFD at the time of enrollment based on TTG IgA levels, DGP IgA levels, and CDAT scores (Table III). The mean enrollment TTG IgA was 3.5 and 2.9 for the control and TEACH groups respectively (normal <4); mean enrollment DGP IgA was 8.5 and 7.4 respectively (normal <10), and median enrollment CDAT scores 11.5 and 11 respectively (<13 indicates good adherence). Indeed, only three participants from the control group and three participants from the TEACH intervention group had an abnormal TTG IgA >4 at the time of enrollment.

Table 3.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measure and Laboratory Data for TEACH Intervention Group and Control Group

| TEACH Intervention Group | |||

| Outcome Measure | Enrollment Scores (n=31) Median (Interquartile Range) | Post-study Scores (n=30) Median (Interquartile Range) | P value |

| Celiac Dietary Adherence Test (CDAT) | 11 (9–14) | 10 (8.3–12.8) | 0.16 |

| NIH PROMIS Global Short Form | |||

| Global Mental Health | 50.8 (44.7–53.3) | 53.3 (48.3–59) | 0.01 |

| Global Physical Health | 50.8 (44.9–57.7) | 57.7 (48.5–57.7) | 0.03 |

| Celiac Symptom Index (CSI) | 27 (22.5–36) | 25.5 (21.3–34.8) | 0.14 |

| Patient Activation Measure (PAM) | 63.1 (54.4–73.8) | 72.5 (60.6–90.7) | 0.01 |

| Control Group | |||

| Outcome Measure | Enrollment Scores (n=30)Median (Interquartile Range) | Post-study Scores (n=30)Median (Interquartile Range) | P value |

| Celiac Dietary Adherence Test (CDAT) | 11.5 (9–13.8) | 11 (8–13) | 0.47 |

| NIH PROMIS Global Short Form | |||

| Global Mental Health | 50.8 (43.5–56) | 53.3 (45.8–58.3) | 0.54 |

| Global Physical Health | 54.1 (47.7–57.7) | 52.5 (48.5–60.9) | 0.75 |

| Celiac Symptom Index (CSI) | 28.5 (22.5–35.5) | 27 (21–32.5) | 0.16 |

| Patient Activation Measure (PAM) | 75 (66.7–83.8) | 77.7 (67.8–90.7) | 0.47 |

| Tissue Transglutaminase IgA (TTG IgA) | |||

| Outcome Measure | TEACH Intervention Mean (SD) | Controls Mean (SD) | P value |

| Enrollment Level | 2.3 (1.2) (n=27) | 3.5 (6.1) (n=27) | |

| Post-study Level | 3.5 (5.6) (n=23) | 2.2 (0.4) (n=22) | |

| % Change | 0.04 (0.3) (n=23) | −0.01 (0.2) (n=22) | 0.37 |

| Deamidated Gliadin Peptide IgA (DGP IgA) | |||

| Outcome Measure | TEACH Intervention Mean (SD) | Controls Mean (SD) | P value |

| Enrollment Level | 7.4 (4.8) (n=26) | 8.5 (8.6) (n=24) | |

| Post-study Level | 6.8 (6.0) (n=23) | 9.6 (14.7) (n=21) | |

| % Change | −0.15 (1.2) (n=23) | 0.08 (0.3) (n=21) | 0.37 |

TTG data omitted for one participant in the TEACH intervention group as labs were drawn after laboratory transitioned to a new form of testing with normal cut-off value <19 rather than <4.

Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures

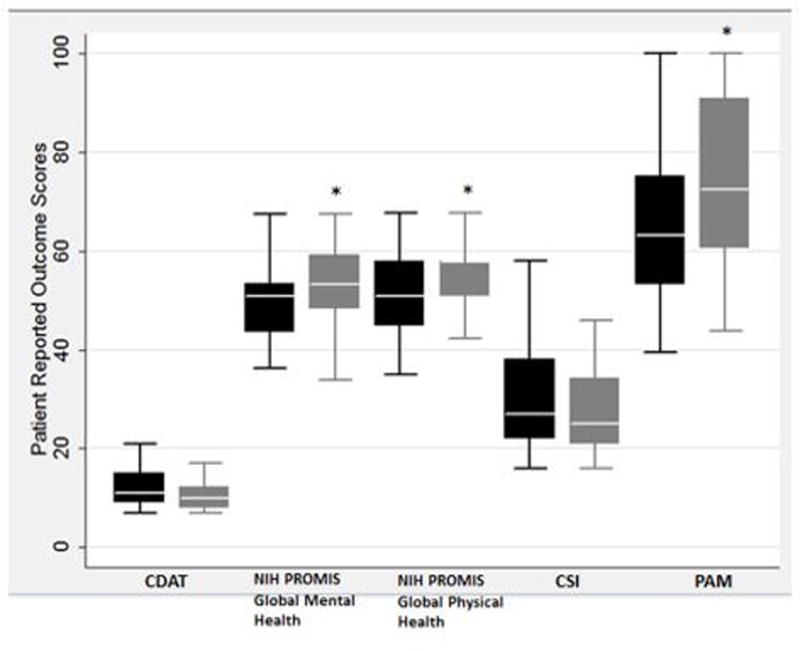

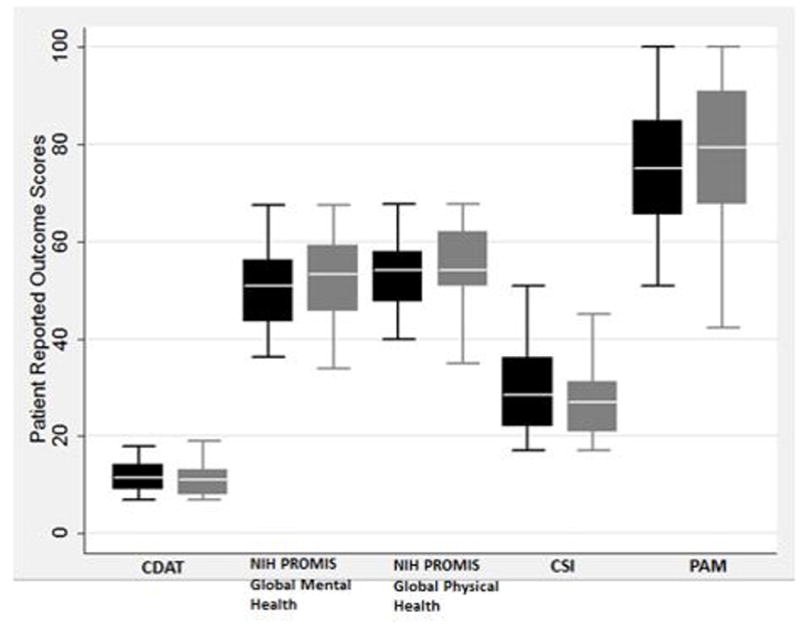

Among the TEACH group, there was significant improvement comparing enrollment scores with three month follow-up scores in patient activation (PAM score 63.1 vs 72.5, P=0.01) and QOL (NIH PROMIS Global Mental Health 50.8 vs 53.3, P=0.01 and NIH PROMIS Global Physical Health 50.8 vs 57.7, P=0.03) (Table III, Figure 2, A). No statistically significant differences were noted in any outcome measure among the control group (Table III, Figure 2, B). There was no statistically significant difference in the percent change in TTG IgA or DGP IgA over the course of the study between the control group and the TEACH group (Table III). However, two participants in the TEACH group with abnormal enrollment TTG IgA levels showed improvement after the three month study intervention.

Figure 2.

a. Box Plots of Patient Outcome Measures for TEACH Group

b. Box Plots of Patient Outcome Measures for Control Group

Black boxes represent enrollment data and gray boxes represent follow-up data for each outcome measure. Asterisk indicates statistically significant data comparing follow-up with enrollment data.

Participants in the TEACH group demonstrated a mean bidirectional text message response rate of 81%. Overall, participants enjoyed the text message intervention; they felt the text messages reminded them to stay gluten-free and that the frequency of messages was appropriate (Table IV; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 4.

Feedback Survey Data for all Study Participants

| Feedback Survey Data | Result Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Would you have preferred to receive text message reminders during the study? | 78% answered Yes (n=32) |

| Overall, did you enjoy the text message reminders? (scale from 0 (not at all), 50 (somewhat), 100 (very much)) | 65.4 (27.3) (n=29) |

| Overall, did you find the text messages reminded you to stay gluten free? (scale from 0 (not at all), 50 (somewhat), 100 (very much)) | 52.2 (34.1) (n=29) |

| How would you describe the text message reminders? (scale from 0 (not frequent enough, 50 (just right), to 100 (too frequent)) | 57.0 (16.6) (n=29) |

| What type of text message did you find most helpful? | Online Resources 27% Humorous Reminders 37% Bidirectional Quiz Questions 37% (n=30) |

| Would you be interested in future studies with text messages over a longer period of time? | 80% answered Yes (n=30) |

Among the TEACH intervention group, the bidirectional text message response rate was 81% with 71% correct responses to the 15 quiz text message questions.

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, we investigated the efficacy of a novel TEACH automated text messaging intervention in improving GFD adherence among adolescents and young adults with CD. Although a statistically significant change in TTG IgA and DGP IgA was not detected among our already adherent study population, we identified improvements in several secondary outcome measures among the TEACH intervention group. A statistically significant improvement in patient activation and QOL as measured by PAM and NIH PROMIS scores, respectively, over the course of the study was observed in the TEACH intervention group. It is important to note that these validated, patient-reported outcome measures increased even among a cohort of patients with baseline GFD adherence. This indicates that an automated text messaging platform for longitudinal patient education and activation such as TEACH benefits patients in optimizing wellbeing not readily captured by traditional markers of disease activity.

We selected four validated measures to assess patient-reported GFD adherence (CDAT), disease symptomatology (CSI), patient activation (PAM), and QOL (NIH PROMIS Global Short Form) as our secondary outcome measures. It should be noted that these measures have only been validated among patients 18 years of age and older. However, the CDAT and the PAM have been used in a pediatric setting in the literature(13,35), and the pediatric PROMIS global short form has 4 of the 7 questions identical to the general PROMIS global short form used in this study(37). The PAM is a unique measure of patient activation that assesses a patient’s ability for disease self-management, collaboration with healthcare providers, prevention of exacerbation, and access to care(36). Increased levels of patient activation have been shown to improve quality and health outcomes among patients managing a chronic disease(36,38). Patient engagement and activation in self-management of a chronic illness such as CD is particularly important among the adolescent and young adult population who are transitioning outside the home and making independent dietary choices, but is applicable to any patient struggling with a chronic disease. Lifelong management of CD with GFD is challenging given mealtime is often a shared, public interaction; a restrictive diet can cause social isolation and misunderstanding of CD(39). This social isolation and high perceived health burden from lifelong GFD therapy among patients with CD can lead to depressive symptoms and negative QOL(40,41). Thus, a behavioral intervention such as TEACH that improves patient activation and QOL among patients with CD, even among a cohort of already adherent participants, is particularly important.

Although we did not find the TEACH intervention to improve serum markers of GFD adherence, this may be due to the natural limitations of a pilot study with a smaller number of participants. We acknowledge a limitation of this study was the potential selection bias in patient recruitment leading to an already adherent population at the time of enrollment and likely dampening any measurable impact the TEACH program intervention may have on adherence. Studies among pediatric patients with CD indicate that TTG IgA and DGP IgA can decline as much as 60% over a three month period with GFD adherence; thus, we anticipated a measurable change was feasible in the study intervention period(42). Though we attempted to recruit participants from a diverse array of geographic location and socioeconomic background, those participants who were willing to complete the surveys and laboratory draws were likely participants who were already following a GFD and somewhat engaged with the long term management of CD. It is unclear why there were significantly more females than males in the control group with our block randomization protocol; we anticipate this would become less impactful with a larger number of participants in future studies. There is also a possibility for a Hawthorne effect among the control group given their awareness of being observed during study enrollment through blood draws and surveys, which could minimize any differences in adherence that may have been present between the control group and intervention group over the course of the study. The study results are thought to be generalizable to the adolescent and young adult CD population given the diverse patient population recruited from across the US, and Pew study statistics indicating prevalence of text messaging in the adolescent population(18).

Mobile health interventions are a growing area of research to enact behavioral change among patients with chronic disease. Ultimately, our study shows that interactive text messages are a feasible, enjoyable intervention among the adolescent and young adult population with CD based on participant feedback (Table IV). Future studies are needed to expand the bidirectional nature of text message interventions to promote more effective communication and personalization of reminders among patients with chronic disease. The TEACH program is a promising behavioral intervention to improve QOL and patient activation in self-management of chronic disease. We look forward to using the TEACH program in larger studies among a variety of chronic illnesses, and developing the interactive nature and personalization of text message content and frequency.

Acknowledgments

Funding provided by NIH (T32DK007056-39), the Elizabeth and Russell Siegelman Postdoctoral Fellowship through the Child Health Research Institute, and the Stanford CTSA (UL1 TR001085) to K.H.. REDCap funding from NIH/NCRR (UL1 RR025744). K.P. supported by NIH (NIDDK094868).

We thank Jennifer Iscol, President of Celiac Community Foundation of Northern California who helped with recruitment by sharing link to study referral website through social media and local contacts.

Abbreviations

- CD

Celiac disease

- GFD

Gluten-free diet

- QOL

Quality of life

- TTG IgA

Tissue Transglutaminase IgA

- DGP IgA

Deamidated Gliadin Peptide IgA

- CDAT

Celiac Dietary Adherence Test

- CSI

Celiac Symptom Index

- PAM

Patient Activation Measure

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Guandalini S, Assiri A. Celiac disease: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Mar;168:272–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill ID, Dirks MH, Liptak GS, Colletti RB, Fasano A, Guandalini S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005 Jan;40:1–19. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebwohl B, Granath F, Ekbom A, Smedby KE, Murray JA, Neugut AI, et al. Mucosal healing and risk for lymphoproliferative malignancy in celiac disease: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Aug 6;159:169–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, Not T, Colletti RB, Drago S, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Feb 10;163:286–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrady ME, Hommel KA. Medication adherence and health care utilization in pediatric chronic illness: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013 Oct;132:730–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanghøj S, Boisen KA. Self-reported barriers to medication adherence among chronically ill adolescents: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2014 Feb;54:121–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGrady ME, Ryan JL, Gutiérrez-Colina AM, Fredericks EM, Towner EK, Pai ALH. The impact of effective paediatric adherence promotion interventions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Care Health Dev. 2015 Aug 9; doi: 10.1111/cch.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurppa K, Lauronen O, Collin P, Ukkola A, Laurila K, Huhtala H, et al. Factors associated with dietary adherence in celiac disease: a nationwide study. Digestion. 2012;86:309–14. doi: 10.1159/000341416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ljungman G, Myrdal U. Compliance in teenagers with coeliac disease--a Swedish follow-up study. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor. 1993 Mar;82:235–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panzer RM, Dennis M, Kelly CP, Weir D, Leichtner A, Leffler DA. Navigating the gluten-free diet in college. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Dec;55:740–4. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182653c85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacCulloch K, Rashid M. Factors affecting adherence to a gluten-free diet in children with celiac disease. Paediatr Child Health. 2014 Jun;19:305–9. doi: 10.1093/pch/19.6.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahana S, Drotar D, Frazier T. Meta-analysis of psychological interventions to promote adherence to treatment in pediatric chronic health conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008 Jul;33:590–611. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sainsbury K, Mullan B, Sharpe L. A randomized controlled trial of an online intervention to improve gluten-free diet adherence in celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108:811–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palermo TM, Wilson AC, Peters M, Lewandowski A, Somhegyi H. Randomized controlled trial of an Internet-delivered family cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain. 2009 Nov;146:205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Jongh T, Gurol-Urganci I, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Car J, Atun R. Mobile phone messaging for facilitating self-management of long-term illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD007459. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007459.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Partridge SR, McGeechan K, Hebden L, Balestracci K, Wong AT, Denney-Wilson E, et al. Effectiveness of a mHealth Lifestyle Program With Telephone Support (TXT2BFiT) to Prevent Unhealthy Weight Gain in Young Adults: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2015;3:e66. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenhart A. Teens, Social Media & Technology Overview 2015 [Internet] Pew Research Center. 2015 Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/

- 19.McGillicuddy JW, Gregoski MJ, Weiland AK, Rock RA, Brunner-Jackson BM, Patel SK, et al. Mobile Health Medication Adherence and Blood Pressure Control in Renal Transplant Recipients: A Proof-of-Concept Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2013;2:e32. doi: 10.2196/resprot.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lua PL, Neni WS. A randomised controlled trial of an SMS-based mobile epilepsy education system. J Telemed Telecare. 2013 Jan;19:23–8. doi: 10.1177/1357633X12473920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arora S, Peters AL, Burner E, Lam CN, Menchine M. Trial to examine text message-based mHealth in emergency department patients with diabetes (TExT-MED): a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2014 Jun;63:745.e6–754.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv Y, Zhao H, Liang Z, Dong H, Liu L, Zhang D, et al. A mobile phone short message service improves perceived control of asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E-Health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2012 Aug;18:420–6. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2011.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow CK, Redfern J, Hillis GS, Thakkar J, Santo K, Hackett ML, et al. Effect of Lifestyle-Focused Text Messaging on Risk Factor Modification in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015 Sep 22;314:1255–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franklin VL, Greene A, Waller A, Greene SA, Pagliari C. Patients’ engagement with “Sweet Talk” - a text messaging support system for young people with diabetes. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franklin VL, Waller A, Pagliari C, Greene SA. A randomized controlled trial of Sweet Talk, a text-messaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc. 2006 Dec;23:1332–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rami B, Popow C, Horn W, Waldhoer T, Schober E. Telemedical support to improve glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Pediatr. 2006 Oct;165:701–5. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolff M, Balamuth F, Sampayo E, Mollen C. Improving Adolescent Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Follow-up From the Emergency Department: Randomized Controlled Trial With Text Messages. Ann Emerg Med. 2015 Nov 23; doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suffoletto B, Kristan J, Chung T, Jeong K, Fabio A, Monti P, et al. An Interactive Text Message Intervention to Reduce Binge Drinking in Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial with 9-Month Outcomes. PloS One. 2015;10:e0142877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Leary ST, Lee M, Lockhart S, Eisert S, Furniss A, Barnard J, et al. Effectiveness and Cost of Bidirectional Text Messaging for Adolescent Vaccines and Well Care. Pediatrics. 2015 Nov;136:e1220–1227. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garofalo R, Kuhns LM, Hotton A, Johnson A, Muldoon A, Rice D. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Personalized Text Message Reminders to Promote Medication Adherence Among HIV-Positive Adolescents and Young Adults. AIDS Behav. 2015 Sep 11; doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1192-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson KB, Patterson BL, Ho Y-X, Chen Q, Nian H, Davison CL, et al. The feasibility of text reminders to improve medication adherence in adolescents with asthma. J Am Med Inform Assoc JAMIA. 2015 Dec 11; doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leffler DA, Dennis M, Edwards George JB, Jamma S, Magge S, Cook EF, et al. A simple validated gluten-free diet adherence survey for adults with celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2009 May;7:530–6. 536–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2009 Sep;18:873–80. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leffler DA, Dennis M, Edwards George J, Jamma S, Cook EF, Schuppan D, et al. A validated disease-specific symptom index for adults with celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2009 Dec;7:1328–34. 1334–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang JS, Terrones L, Tompane T, Dillon L, Pian M, Gottschalk M, et al. Preparing adolescents with chronic disease for transition to adult care: a technology program. Pediatrics. 2014 Jun;133:e1639–1646. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004 Aug;39:1005–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Institute of Health; 2015. [cited 2016 Dec 29]. NIH PROMIS Pediatric Instrument Banks [Internet] Available from: https://www.niams.nih.gov/funding/Funded_Research/PEPR/promis_instruments.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 May;27:520–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1931-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bacigalupe G, Plocha A. Celiac is a social disease: family challenges and strategies. Fam Syst Health J Collab Fam Healthc. 2015 Mar;33:46–54. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simsek S, Baysoy G, Gencoglan S, Uluca U. Effects of Gluten-Free Diet on Quality of Life and Depression in Children With Celiac Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Sep;61:303–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah S, Akbari M, Vanga R, Kelly CP, Hansen J, Theethira T, et al. Patient perception of treatment burden is high in celiac disease compared with other common conditions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Sep;109:1304–11. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugai E, Nachman F, Váquez H, González A, Andrenacci P, Czech A, et al. Dynamics of celiac disease-specific serology after initiation of a gluten-free diet and use in the assessment of compliance with treatment. Dig Liver Dis Off J Ital Soc Gastroenterol Ital Assoc Study Liver. 2010 May;42:352–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]