Abstract

Differential equation models can be used to describe the relationships between the current state of a system of constructs (e.g., stress) and how those constructs are changing (e.g., based on variable-like experiences). The following article describes a differential equation model based on the concept of a reservoir. With a physical reservoir, such as one for water, the level of the liquid in the reservoir at any time depends on the contributions to the reservoir (inputs) and the amount of liquid removed from the reservoir (outputs). This reservoir model might be useful for constructs such as stress, where events might “add up” over time (e.g., life stressors, inputs), but individuals simultaneously take action to “blow off steam” (e.g., engage coping resources, outputs). The reservoir model can provide descriptive statistics of the inputs that contribute to the “height” (level) of a construct and a parameter that describes a person's ability to dissipate the construct. After discussing the model, we describe a method of fitting the model as a structural equation model using latent differential equation modeling and latent distribution modeling. A simulation study is presented to examine recovery of the input distribution and output parameter. The model is then applied to the daily self-reports of negative affect and stress from a sample of older adults from the Notre Dame Longitudinal Study on Aging.

Keywords: differential equation, daily diary, intraindividual observations, negative affect, resiliency

Intraindividual variability, states, or fluctuations of constructs in psychology present a challenge for statistical modeling because of the nonlinear, short-term, relatively reversible changes that are often observed (Nesselroade, 1991). One approach to modeling these data has been through the consideration of the relationships between a person's current state and how that person is changing over time. One model that has made frequent appearances in the psychological literature is that of a damped linear oscillator, also known as the model for a pendulum with friction (e.g., Bisconti, Bergeman, & Boker, 2006; Boker & Graham, 1998; Boker & Laurenceau, 2005; Boker, Leiben-luft, Deboeck, Virk, & Postolache, 2008; Chow, Ram, Boker, Fujita, & Clore, 2005; Montpetit, Bergeman, Deboeck, Tiberio, & Boker, 2010). In this model, a construct fluctuates around some equilibrium, which can be thought of as the “typical” state of a person or the person's level on some trait; the equilibrium can be a constant or can change with time depending on model specification. The fluctuations around the equilibrium are not random but rather have self-regulatory or homeostatic-like properties, such that when a person's state is far from his or her equilibrium, like a pendulum swinging far from its resting position, change in the direction of the equilibrium is expected.

The damped linear oscillator model is particularly interesting for constructs for which a person has a typical level around which there is variation. This type of model may be useful for describing data such as those in Figures 1A and 1C, in which the construct fluctuates around a nonzero equilibrium. The pendulum model may be a poor model, however, for many constructs: in this model the fluctuations above and below the equilibrium—the place the pendulum would come to rest. These fluctuations are assumed to be of equal magnitude (same “height”) above and below the equilibrium, although there does not have to be an equal number of fluctuations above and below the equilibrium (there could be more peaks or more valleys). Constructs for which the pendulum model will be a poor representation include those in which the equilibrium is the floor or ceiling of measurement, thereby eliminating the possibility of fluctuating around the equilibrium. Figures 1B and D are examples of data that may be poorly described by the pendulum model, as measurements in these figures experience a floor effect and do not show equal magnitude fluctuations around their means.

Figure 1.

Examples of data for which the pendulum model may be appropriate (A and C) and data for which the pendulum model is likely to be inappropriate (B and D). Plots are daily self-reports of stress (A and B) and negative affect (C and D) made by older adults.

The plots in Figure 1 are daily diary data from the Notre Dame Longitudinal Study on Aging. Figures 1A and 1B represent a measure of stress, and Figures 1C and 1D represent a measure of negative affect. Although some older adults demonstrated fluctuations on these constructs that might be appropriately modeled with the pendulum model (e.g., Figure 1A and 1C), a large proportion exhibited a floor effect (e.g., Figures 1B and 1D). Rather than exhibit continuous fluctuations around a nonzero equilibrium, many older adults reported having little or no stress or negative affect. The floor effect persists despite efforts to include lower threshold items, that is, items that would presumably require less of a construct (e.g., negative affect) to endorse; for example “unhappy” and “worried” are a lower threshold items than “depressed” and “anxious.” The problems observed with modeling data of these type were the motivation for developing this modeling strategy.

One approach to these data might be to think of the different patterns as representative of two differing populations of older adults: one with a more symmetrical distribution and one with a distribution that is more similar to an exponential distribution. It should be noted, however, that although we can identify these two qualitatively different groups, there are many individuals with time series that fall between these two extremes, suggesting a continuum within a single population rather than two distinct populations. This then raises the question, if a pendulum model is inappropriate to model these data for many individuals, is there a single model that could describe both symmetrical and very skewed responses without having to posit the existence of two discrete populations?

The following describes a differential equation model—that is, a model using derivatives to express the level of constructs and how the constructs are changing with respect to time—based on the concept of a reservoir. This model parallels the level of a construct with the height of the liquid in a reservoir, and assumes that there are events or actions that contribute to both increasing the level of the construct (adding liquid; e.g., stressors) and decreasing the level of the construct (removing liquid; e.g., engaging coping resources). This model may be useful for describing constructs for which there are fluctuations around a nonzero equilibrium, but also cases in which there is a floor effect.1 The following pages introduce the reservoir model and demonstrate how it can be implemented with structural equation modeling (SEM). This model uses a novel combination of methods, so simulations were used to examine parameter recovery. The model was then applied to the daily self-reports of negative affect and stress of a sample from the Notre Dame Longitudinal Study on Aging.

Reservoir Model Introduction

Figure 2 is a representation of the reservoir model. Liquid enters the reservoir from a pipe suspended over the reservoir. There is an open pipe at the bottom of the reservoir, which reduces the height of the liquid (h). The height of the liquid varies over time depending on the volume of the inputs and the rate of output.

Figure 2.

Pictorial representation of the reservoir model. The height of the liquid h corresponds to the level of a construct at some time.

This model can describe constructs with both symmetrical and skewed distributions. Consider, as an example, ratings of stress. As one proceeds from day to day, stressful events occur. As stressors occur, they contribute varying amounts to one's “stress level,” which is depicted as the height h of the liquid in the reservoir. As stressful events accumulate, the height of the liquid in the reservoir rises—or colloquially, the stresses “add up.” Consequently, individuals are expected to provide higher ratings of their stress. Instead of allowing stresses to increase unabated, the model allows for stress to be dissipated.

The model, as implemented, does not specifically address the sources of the inputs or mechanisms by which dissipation occurs; the inputs could reflect a variety of sources of stress, and the dissipation parameter could reflect a combination of stress-reducing mechanisms (e.g., passive means like not working on weekends, taking time to “cool off”; active means like exercising to “blow off steam”).

One way to understand the reservoir model is in relation to the damped linear oscillator model. Like a pendulum, this model can produce values that fluctuate around some nonzero equilibrium, or typical state. These cases occur when the average input over time is similar to the average output; in such a case the height of the liquid would be at some level and, despite positive and negative fluctuations, remain constant on average because of the balance of inputs and outputs. This model also allows for the possibility that the average output could be larger than the average input. In such a case the reservoir will tend to be empty (floor effect), although stresses (inputs) may still perturb the height of the liquid for a short time. The key difference between the pendulum and reservoir models is that whereas the pendulum model is focused on the idea of an equilibrium state, around which a person varies both above and below, the reservoir model shifts focus toward how inputs and outputs contribute to the level of a construct. Figure 3 shows some of the patterns that can be produced with the reservoir model, when plotting the observed height of the reservoir liquid over time; this figure demonstrates both nearly symmetrical fluctuations around a nonzero equilibrium (e.g., Figures 3A and 3D) and skewed distributions (e.g., Figures 3C and 3E).

Figure 3.

Examples of trajectories produced by the reservoir model with 10% measurement error. Each subsequent row depicts reservoirs in which the frequency of input events is decreasing. Figures show reservoirs with smaller (A–C) and larger (D–F) output rates. h = height.

The present article focuses on moderately long time series (e.g., 25–100 observations)2 in which only the level of a single construct has been measured; we do not assume that multiple time series have been collected to represent the level of inputs and outputs of a construct. Rather it is assumed that the inputs and outputs are not directly observed, but that the fluctuations in the level of a construct can be used to infer information about inputs and outputs. In examining the level of only a single construct, the change in the volume of the reservoir dVreservoir will be equal to the volume of inputs Vin minus the volume of outputs Vout (assuming volumes equal to or greater than 0):

| (1) |

The change in volume of the reservoir can be expressed as the change in the height of the liquid dh multiplied by the cross-sectional area of the reservoir Areservoir; similarly the input and output volumes will be equal to the velocity of the liquid in or out (vin and vout) multiplied by the cross-sectional areas of the pipes (Ain and Aout) times the change in time dt (Tipler & Mosca, 2007). If we were to substitute this into Equation 1,

| (2) |

In a physical reservoir the rate of outflow is related to the height of the liquid in the reservoir, such that the higher the height of the liquid, the higher the flow rate. For example, vout = ch where c is a constant that is related to gravity.3 If we were to substitute this into and rearrange Equation 2,

| (3) |

This equation states that the change in the height of the reservoir liquid, dh/dt (first derivative, the rate of change with respect to time), is equal to a dissipation term β multiplied by the height of the liquid in the reservoir h (zeroth derivative, level of a construct at some time) plus a distribution of inputs εinputs. As we are considering only volumes that are positive or equal to 0, εinputs must consist of a distribution with no negative values. In this equation specifics about the reservoir such as Ain, Aout, and Areservoir have been collapsed into fewer parameters. If one measures only a single time series and one is not manipulating characteristics of the reservoir, it is impossible to estimate these parameters separately; furthermore, any attempt to estimate such parameters would need to consider first whether a psychological analogue to a physical reservoir exists. If one believes that such an analogue exists for a construct such as stress, it may be possible to disentangle differences in parameters such as Areservoir, which would related to total reservoir capacity, through experimental manipulations of stressors.

The parameter β, which should be less than or equal to 0 so as to correspond to the output of a positive volume of liquid, describes the rate at which liquid dissipates from the reservoir. To understand β, consider the similarity of Equation 3 with the model of exponential decay: dN/dt = −λN (Tipler & Llewellyn, 1999). Frequently the model of exponential decay is understood in terms of half-life, or the time required for a value to be reduced by half.4 When starting two reservoirs at the same height, if there are no additional inputs, the reservoir with a larger negative value β (e.g., −.5) will empty much more quickly than the reservoir with a smaller negative value β (e.g., −.1). The parameter β, often called the decay constant in the physical sciences, might be better thought of as an average dissipation constant in the social sciences. The time required to dissipate a fixed percentage of one's current reservoir height will be 5 times longer if β = −.1 than if β = −.5, assuming no additional inputs.

Aside from the exponential decay model, the reservoir model is closely related to the continuous-time autoregressive model (Delsing & Oud, 2008; Oud, 2007; Oud & Jansen, 2000). The continuous-time autoregressive model, which can be expressed as

| (4) |

predicts the first derivative dx/dt of a time series using a constant A times the state of the time series x, plus an error term G(dW/dt) that produces independent, normally distributed errors. Exchanging x with h and A with β, this equation appears very similar to that of the reservoir model (Equation 3). The key difference is in the error terms. The continuous-time autoregressive model assumes that the inputs follow a normal distribution with mean of 0. The model presented here assumes that the term εinput must be made up of a distribution in which all values are greater than or equal to 0—that is, there are no inputs that remove liquid from the reservoir. The change in the distribution errors dramatically changes the interpretation of β compared to A; whereas A conveys how related observations are across time, β conveys change only in the negative direction across time (i.e., dissipation). The continuous-time model also specifies a very specific error process, the Wiener process, which is a continuous-time error process; the reservoir model does not assume a specific distribution, although it might be expected that the distribution of inputs will typically be skewed; nor is it specified as a continuous-time process, as this would not be possible without selecting a specific distribution. Selection of a specific distribution of inputs, unlike what is considered here, may also allow for this model to be fit with methods other than those described here, such as using the state space modeling techniques in the time series literature (Durbin & Koopman, 2001; Ozaki & Iino, 2001).

Reservoir Model Implementation

Latent Differential Equation Modeling

The implementation of the reservoir model as a structural equation model consists of a combination of two pieces: (a) a method to estimate the derivatives of a time series and the differential equation model, and (b) a method that allows for the estimation of a nonnormal distribution of inputs. The estimation of the first dh/dt and zeroth h derivatives of a time series can be accomplished with several methods that allow for the estimation of derivatives from a time series (e.g., Boker, Neale, & Rausch, 2004; Boker & Nesselroade, 2002; Deboeck, 2010). Once the derivatives of the time series are estimated, the relationship β can be estimated by regressing the zeroth derivative onto the first derivative.

Latent differential equations (LDEs) are similar to latent growth curve modeling, in that by constraining the paths from the latent variables to the observed variables, the latent variables take on specific interpretations (i.e., derivatives of a particular order). The zeroth and first derivatives, which convey the level of a construct at some time and how it is changing with respect to time, are directly related to intercept and slope. The crucial difference is that rather than estimating the level and change for an entire time series, these estimates will be made for many, smaller pieces of the time series. LDEs are akin to running a regression on the first few observations of a time series and estimating the intercept and slope, then the next few observations, then the next few observations, etc.

The estimation of the zeroth derivatives (level) and first derivatives (change) for many small segments of a time series is accomplished through the creation of an embedded matrix. The embedded matrix consists of several columns, each of which consists of a replicate of the time series offset in time (Boker et al., 2004). For example, the time series x = {x1, x2, …, xt} can be used to create the embedded matrix

| (5) |

By rearranging the data in this way, one will note that each row consists of a small piece of the original time series. If this were a latent growth curve, each row would correspond to the scores of an individual person, and by using fixed loadings one would produce estimates of the intercept and slope. Here each row corresponds to a piece of the time series, and by using fixed loadings we produce estimates of the zeroth and first derivatives; the latent constructs represent differences in the level and change of values over the length of the time series.

As this article uses LDE to estimate the derivatives of a time series as latent variables (Boker et al., 2004), the model shown in Equation 3, dh/dt = βh + εinputs, represents the relationship between latent derivatives. The derivatives, dh/dt and h, if represented as a matrix η, are related to the embedded matrix through the equation

| (6) |

where XE represents the embedded matrix X with 1 to E embed-dings, and Λ is the fixed matrix of loadings. The matrix Λ consists of a column of 1s and a column that increments proportional to time (e.g., Day 0, Day 1, Day 2 …); for the second column the initial time t = 0 is set to the middle column of the embedded matrix (for an odd number of embeddings) or between the two center columns (for an even number of embeddings). This article will utilize an embedding dimension of 2, and therefore,

| (7) |

It should be noted that ε is not the same as εinputs; whereas εinputs represents the stochastic part of the true construct consisting of only positive values (i.e., dynamic or process errors), ε consists of normally distributed measurement error.

One important consideration is the number of embedding dimensions used to create the embedded matrix. The embedding dimension determines the number of observations used to estimate each derivative; that is, each row consists of the values that will be used to estimate the derivatives at a particular time. The embedding dimension must be large enough that there are enough observations in a single row to estimate the desired derivatives. For example, at least two observations are required to estimate the first derivative (linear slope).

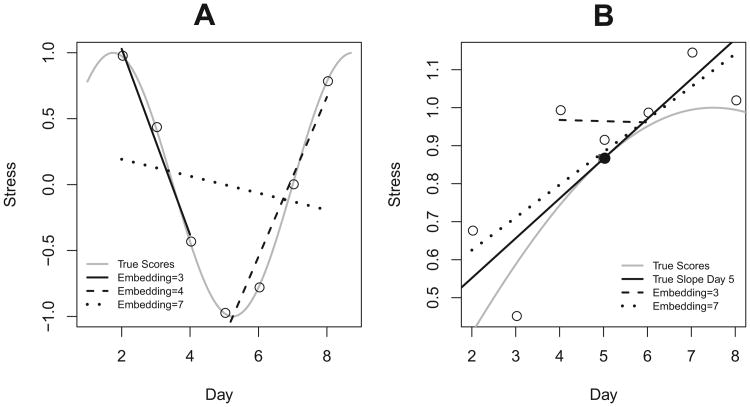

It is also important to consider how quickly the construct of interest is changing relative to the sampling rate, that is, the rate at which data are being collected. Figure 4 demonstrates the two primary, diametrically opposing goals in selecting an embedding dimension. In Figure 4A, a weekly cycle is shown (gray line) with daily measurements (circles). The first derivative is estimated with embedding dimensions—that is, the number of observations used to estimate the derivative—of 3, 4, and 7. As can be seen, the lower two embedding dimensions do a fair job of mimicking the true change, while the embedding dimension of 7 averages over much of the change of interest. Figure 4B presents the true values of a construct (gray line) measured with error (circles). If one is estimating the slope (solid black line) at Day 5 (filled circle), one could use differing embedding dimensions (dashed and dotted lines); the embedding dimension of 3 is heavily influenced by the noise in the system, whereas this is less true of the estimate produced with an embedding dimension of 7.

Figure 4.

In Figure 4A, the true system (gray line) is measured daily (circles); recovery of the first derivative depends on embedding dimension (other lines). In Figure 4B, the true system (gray line) is measured with error (circles). If trying to estimate the true slope (solid black line) on Day 5 (filled circle), the efficiency of the estimate can depend on the embedding dimension (dashed lines). In Figure 4A, smaller embedding dimensions are advantageous, whereas in Figure 4B, larger embedding dimension are advantageous until one begins to average over true change of interest.

These then are the two goals in selecting an embedding dimension: (a) select an embedding dimension small enough that one is not averaging over true change of interest and (b) select an embedding dimension large enough that one averages over fluctuations due to measurement error. There is not a simple rule of thumb to guide selection of the embedding dimension, because it is closely tied to the rate at which a construct is changing. Thus, the embedding dimension must be determined based on theories related to the process of interest and the sampling rate selected by the researcher. Unfortunately, this is often as much a product of theory as factors such as convenience, funding. and participant burden. Because in psychology it is not always clear over what span of time true change of interest occurs, embedding dimensions that are on the smaller side (e.g., 3–5) are common in the literature (e.g., Bisconti et al., 2006; Boker & Graham, 1998; Boker & Laurenceau, 2005; Boker et al., 2008; Chow et al., 2005; Montpetit et al., 2010). Even when unsure of the rate of change of the true system, researchers must keep in mind that the selection of embedding dimension, in combination with the sampling rate of the data, affects the time scale over which relationships will emerge and influences the findings that emerge from these models (Deboeck, Montpetit, Bergeman, & Boker, 2009). For example, a researcher collecting daily measurements could estimate derivatives over a 4-day span, which will highlight processes occurring over the span of several days, but those processes may differ from intraday processes.

Latent Distribution Modeling

The second piece of the structural equation model is a method to estimate the inputs (εinputs), which cannot have negative values and are likely to be positively skewed (many small events, few large events); consequently a typical SEM error variance term will not suffice. One approach to approximating nonnormal error distributions is with latent distribution modeling (LDM; Heinen, 1996; Markon & Krueger, 2006a, 2006b). In LDM one uses latent classes with differing characteristics (mean value, class probability) to approximate a continuous distribution. Whereas in mixture modeling each mixture component represents a distribution, often a normal distribution with the mean and variance estimated, in LDM the components are homogeneous such that only a mean is estimated and not its variance (Dolan & van der Maas, 1998).

For example, if estimating the distribution in Figure 5A (gray line), one could assign each class to have a different mean (arrows). The probability of each class is then estimated (black vertical lines), thereby approximating the underlying distribution. The advantage of using LDM for the reservoir model is twofold: (a) the latent classes can be assigned means that are greater than or equal to 0, thus producing a distribution with only positive values, and (b) as the probability of each class is freely estimated, the inputs can follow any distribution—for example, Figures 5B through 5D can be produced by changing the estimated probability of each class.

Figure 5.

Examples of the estimation of continuous distributions with latent distribution modeling. Each class (arrows; A) has a different mean (position of vertical black lines) and probability of occurrence (height of vertical black lines). Unlike mixture modeling, the classes do not represent normal distributions—each class represents a mean with 0 variance.

Combining LDE and LDM

Figure 6 shows the reservoir model with the columns of the embedding matrix being represented by Xt and Xt + 1. The latent variable c represents the estimated latent classes. The latent variables h and dh/dt are the latent derivative estimates, which are identified by fixing the paths from the latent derivatives to the columns of the embedded matrix. The paths for the zeroth derivative are set to 1. The paths for the first derivative reflect the spacing of the observations in time, with t = 0 occurring between the two observations. The relationship between derivatives, β, is a regular structural equation model path; this path should be less than or equal to 0—otherwise there would be liquid back-siphoning into the reservoir—but we have not constrained it for the analyses done in this article.

Figure 6.

Structural equation model of the reservoir model. The values μc are moderated by the latent classes (c). The values of μc are fixed to a range of values greater than 0. The class probabilities of are freely estimated. The latent estimates of the zeroth (h) and first (dh/dt) derivatives are identified by fixing all paths to the columns of the embedded matrix (X1 to X2). The parameter β, latent variances, and observed variable variances are the same for all classes.

The values of μc are moderated by the latent classes. The μc of the first class was fixed to equal to 0, and all subsequent class means were estimated. To ensure that all means were positive, and to constrain the estimation problem, the mean of each subsequent class was constrained to be larger than the prior class. The probability of each class was estimated without constraint, save that the probabilities must fall between 0 and 1 and that they must sum to 1, thus allowing for a variety of nonnormal distributions with all positive values to be estimated.

As highlighted earlier in Equations 3 and 6, in the present application we will aim to estimate both dynamic/process error due to the stochastic inputs εinputs using LDM and measurement error ε (Xt and Xt + 1 variances). It was anticipated from the mixture modeling literature that varying the starting values might be wise to ensure the identification of a global maximum in the likelihood. In addition to varying the values of β, the number of classes for the LDM were varied to try to best approximate the unobserved distribution of inputs. The minimum Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to identify the best fitting model. As this model represents a novel combination of LDE and LDM, we begin by presenting a simulation study that examines recovery of the parameter β and characteristics of the input distribution; this is then followed by an applied example that relates the reservoir model estimates, when applied to stress and negative affect, to trait neuroticism.

Simulation Study

Time series with known characteristics were simulated and analyzed with the reservoir model under a variety of conditions to examine how well estimates of the dissipation parameter β and mean and variance of the input distribution can be recovered.

Method

Simulated data generation

Data were generated by specifying a random initial value drawn from an exponential distribution with a rate equivalent to that used to generate the random inputs (discussed shortly). Each observation x(t + 1) was calculated by forward-integrating the model (dh/dt = βh) from x(t) to some random point between the two observations x(t + u), 0 ≤ u ≤ 1, drawn from a uniform distribution. A random input was added, drawn from a exponential distribution with constant decay rate. The model was then forward-integrated from x(t + u) to x(t + 1). This process allowed the random events to occur at any time between subsequent observations, thereby not making the assumption that the random inputs occur at the same moment that observations are made. Between each pair of points a number from a random uniform distribution was drawn to determine whether an input would be added; this allowed the frequency of inputs to vary. The frequency of inputs was varied such that inputs occurred between every pair of observations (100%), on average every other observation (50%), on average every fourth observation (25%), or on average every eighth observation (12.5%); these conditions were created to be consistent with significant events affecting a construct either daily, three to four times per week, approximately biweekly, or approximately weekly, assuming daily measurements. The decay rate of the exponential distribution was selected to be either .50, .75, or 1.00; this, combined with the frequency of inputs, varied both the mean and the variance of the inputs.

The time series generation process was repeated 500 times prior to beginning the generation of each time series, thereby randomizing the initial observation. Independent, normally distributed observations with mean 0 were added to the time series after generation as measurement error. For cases in which the measurement error produced a value less than 0 (i.e., the container holds negative amounts of liquid), the value of the time series was set equal to 0 (i.e., no liquid).5 The variance of the measurement error was set so that it would equal 10% of the total variance. Values of β were varied from −.10 to −.90 in increments of −.10. Time series lengths of 25, 50, and 100 observations were simulated. Examples of time series were presented in Figure 3. The β values, variation in input distribution, frequency of inputs, and time series lengths were crossed (324 conditions), and 500 time series were analyzed per condition (162,000 total time series).

Analysis

Simulated time series were analyzed with the package OpenMx in the statistical program R (Boker et al., 2011; R Development Core Team, 2012). The structural equation model was constructed according to Figure 6; commented code is provided in Appendix A, and updated versions of the code will be maintained on the website of the first author. Each time series was analyzed with two to eight classes,6 and within each number of classes 11 start values for β were used, equally spaced across a range from −1 to 0. The probability of each class was freely estimated; starting values consisted of a uniform distribution. Variances of the observed variables and derivatives were constrained to be greater than 0. The best fitting model was chosen by selecting the model with the minimum AIC.

For the latent distribution modeling step, starting values for the means of the classes for the first derivative were specified. Generalized orthogonal local derivative estimates (GOLD; Deboeck, 2010) were used to estimate the zeroth and first derivatives of each time series. Using these estimates, we estimated the maximum input value by rewriting Equation 3, that is,

Given an estimate of the maximum input, the means of the latent classes μinput were fixed to be equally spaced from 0 to the maximum input. The number of divisions was equal to the number of latent classes. Only the mean of the first class, which was set to 0, was fixed. All other class means were constrained to be larger than the mean of the previous class.

The recovery of three parameters was examined: the dissipation parameter (β), the mean of input distribution (μinput), and the variance of input distribution ( ). The parameter β was estimated through the model-fitting process. The input distribution parameters were estimated with the estimated probabilities pc of each input class and the means μc of each class. The estimate of the average input distribution μinput was calculated as

| (8) |

where n is the number of classes. The estimate of the variance of the input distribution was calculated as

| (9) |

The true values of β were specified as a simulation condition, and the true values of μinput and were calculated from the properties of the exponential distribution used to generate inputs and the frequency of events.

Results

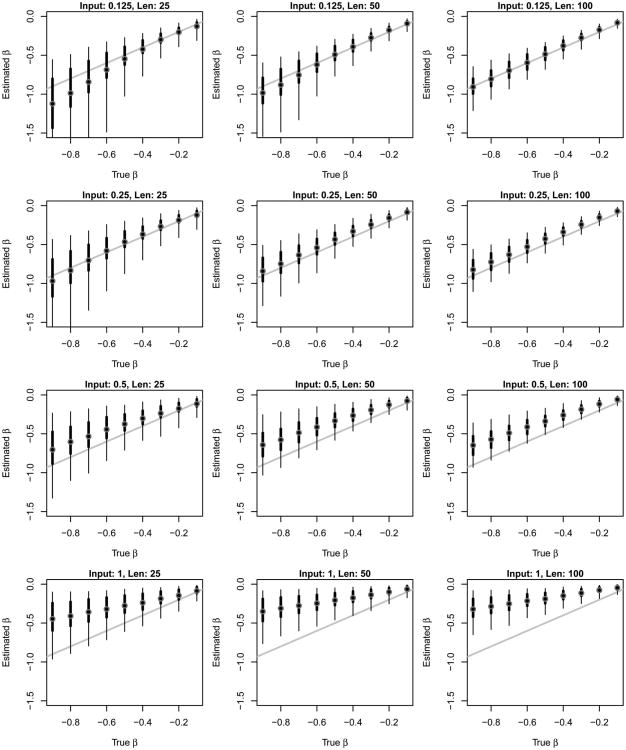

Dissipation parameter β

Figure 7 compares the simulation estimates and true values of the dissipation parameter β; in this figure the circle represents the mean of the estimates, the pair of successively thinner lines represent the 50% and 90% bounds, and the heading over each figure indicates the frequency of inputs (Input) and the length of the time series (Len). Despite the very wide range of conditions examined in these simulations, a correspondence between the true and estimated values is observed across a wide range of true values, input frequencies, and time series lengths. The cases that do show bias can be summarized with two points. The first is that as inputs become more frequent (e.g., 100% condition), the estimates of β become increasingly underestimated, particularly for large values of β. The second is that some bias appears to be present in short time series, even when the frequency of inputs in low (e.g., 12.5%, Len = 25).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the simulation estimates and true values of the dissipation parameter β. The mean estimates are displayed with a circle, and the 50% and 90% bounds are shown with successively thinning lines. The input frequency (Input) is varied across rows, and the time series length (Len) is varied across columns. The diagonal gray line represents equality.

Input distribution mean: μinput

Figures 8A and 8B show examples of the estimates of μc and pc, the class means and the probability of each class, produced by two time series (black lines). The gray lines show the distribution of the true inputs, if they are categorized based on the closest μc (gray line). Both the position of the means and the probability of each class were allowed to vary in the estimation procedure; the number of classes was determined by which model produced the lowest AIC.

Figure 8.

Plots A and B show examples of the estimates' mean μc and the proportion for each mean pc (black vertical bars). The true inputs have been categorized based on the closest μc (gray line). Plots C and D consist of estimates of the input distributions for negative affect and stress based on the applied data example.

Figure 9 compares the estimated mean input (Equation 8) to the means of the distributions from which the inputs were drawn; note that a square-root transformation has been used to make differences more apparent. As with the previous figure, the circle represents the mean of the estimates, the pair of successively thinner lines represent the 50% and 90% bounds, and the heading over each figure indicates the dissipation parameter ((3) and thelength of the time series (Len). Because the previous results suggest that the input frequency is of importance, the figures are divided into two parts with vertical lines; the left section contains results with input frequencies of ≤50%, and the right part contains results with input frequencies of 100%. As with the previous results, the estimates of the mean input frequencies generally correspond to the true distribution of means, but as before, the estimates tend to be biased at higher input frequencies.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the simulation estimates and true values of the mean of the input distribution μinput. The mean estimates are displayed with a circle, and the 50% and 90% bounds are shown with successively thinning lines. The dissipation parameter (β) is varied across rows, and the time series length (Len) is varied across columns. The diagonal gray line represents equality. Text and vertical lines in the plots indicate that the results on the left side of each plot represent input frequencies of ≤50% and results on the right-hand side represent input frequencies of 100%.

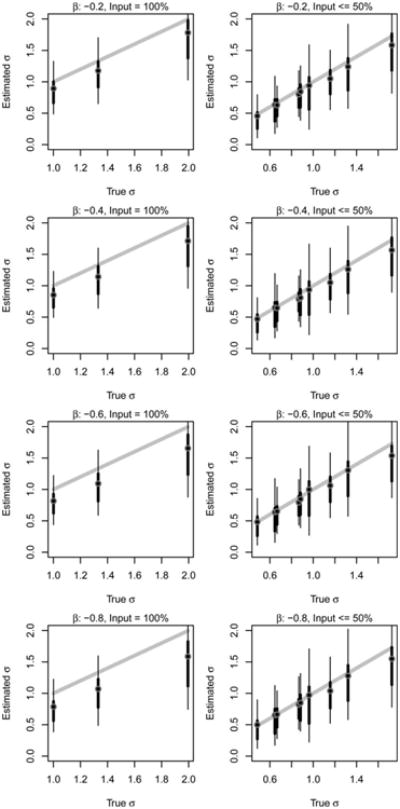

Input distribution variance

Figure 10 compares the estimated variance of the input distribution (Equation 9) to the variance of the input distributions. Note that a square-root transformation has been used, not because of an inherent interest in standard deviations, but to make differences more apparent; only results for time series length 50 are presented, as the other length conditions produced similar results. As with the previous figures, the circle represents the mean of the estimates, the pair of successively thinner lines represent the 50% and 90% bounds, and the heading over each figure indicates the dissipation parameter β and the input frequency (Input). Overall the estimates of the input frequency variance tend to be related to true variance. As before, the estimates tend to be biased when the input frequency was 100%. The observed 50% and 90% ranges are wide relative to the range of the true values, suggesting that these estimates may be prone to large estimation errors.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the simulation estimates and true values of the input distribution variance . The mean estimates are displayed with a circle, and the 50% and 90% bounds are shown with successively thinning lines. The dissipation parameter (β) is varied across rows, and the input frequency (Input) is varied across columns. The diagonal gray line represents equality. Results are for time series of length 50.

Discussion

This simulation examined the estimated dissipation parameter β and two statistics describing the input distribution: the mean μinput and variance . The estimates of β and μinput were reasonable across a wide variety of conditions, including relatively short time series. The simulation results, however, also suggest three important considerations for researchers applying this model.

First, one consistent exception to producing reasonable estimates was when the frequency of input exceeded 50%, although the effect tended to be more pronounced as the dissipation parameter became larger. The 100% input frequency condition was selected to draw attention to the importance of the relationship between the sampling rate of observations, the rate of change of a construct, and the embedding dimension. Figure 11 shows a construct measured with error (gray line) that is changing quickly (many input events, indicated by arrows) relative to the rate that observations are being made (circles). As the construct is changing quickly relative to the rate of observation, the result is a poor estimate of the first derivative (solid black line, embedding dimension of 4).

Figure 11.

If a construct measured with error (gray line) is changing frequently due to events (arrows), the frequency of observations (circles) can affect the recovery of the parameter β. Frequent events (arrows) combined with infrequent observations (circles) can lead to poor estimates of derivatives (solid black line). More frequent observations would be required to get reasonable derivative estimates (dashed black line). h = height.

With stress as an example, this pattern would represent a person with frequent stressors—Monday fender bender, Tuesday grant rejection, Wednesday argument with spouse, Thursday hard drive crash. Even if this person is dissipating each large input quickly, if you see this person only once a day, he might appear consistently stressed; however, if you talked with him several times during the day, you might observe that in the evenings the person has dissipated the stress associated with each event. One must consider that the combination of embedding dimension (4) and sampling rate (perhaps daily) is the span over which derivatives are being estimated (4 days). The sampling rate and embedding dimension limit the time scale over which relationships are applicable. The combination of sampling rate and embedding dimension indicate the shortest period over which change is being captured; changes occurring over shorter periods may not be modeled well.

Second, it is important to note that there appears, in some conditions, bias that is related to the length of the time series. Researchers collecting time series of vastly differing lengths—for example, some subjects with 25 observations and some with 100—should be concerned that the variation observed in estimates could be a function of time series length as much as the process of interest. Researchers predicting reservoir estimates with a large range of time series lengths should check that differences do not occur when one controls for time series length.

Third, it should be noted that the width of the confidence intervals for β, μinput, and all vary as a function of their true values. The error in estimation is important to note, as many statistical techniques (e.g., ordinary least squares regression) assume homogeneity of variance—that the variance of the error in the dependent variable is a constant. If the estimates from this model are used as the dependent variable in another model—for example, to examine what might predict a high or low dissipation parameter—methods such as the wild bootstrap may be required to produce reasonable confidence intervals for hypothesis testing due to the assumption violation (Flachaire, 2005).

The current simulation focused on an embedding dimension of 2. In simulations not presented here, higher embedding dimensions were examined. As it is to be expected, it was found that low bias results tended to occur when inputs were relatively rare, as higher embedding dimensions average over more data to create each derivative estimates. Researchers considering a system with relatively infrequent inputs could consider using a higher embedding dimension to better average over measurement error; a system with an average of less than one input per eight observations should incur relatively little bias in estimates with an embedding dimension of 4 (based on simulations not shown here). In interpreting the result, researchers should keep in mind that the embedding dimension and sampling rate place constraints on the time scale over which these results offer evidence. With an embedding dimension of 4 and daily observations, derivative estimates would average over changes that come and go within less than 4 days, and consequently the reservoir estimates would need to be thought of as not describing daily inputs and outputs of stress, but as describing multiday inputs and outputs.

Application to Data

The following applies the reservoir model to data from the Notre Dame Longitudinal Study on Aging. The data consist of daily self-reports of negative affect and stress from a sample of older adults. For each individual's time series, the reservoir model was fit to the two time series, and relationships between the model estimates and trait neuroticism were examined.

Method

Participants consisted of a subsample from the Notre Dame Longitudinal Study of Aging (see Wallace, Bergeman, & Maxwell, 2002, for details). Following the initial questionnaires assessing various aspects of the aging process, participants were invited to participate in a 56-day daily diary study. Eighty-six individuals were invited to participate, of which 66 agreed to participate. Participants who began the daily diaries were predominantly older (M = 79 years, SD = 6.21), female (75%), living either alone (54%) or with a spouse (45%), educated (98% through high school, 61% some post–high school), and White (90%; 5% African American, 5% Hispanic).

The measures consisted of negative affect and stress time series, and a measure of trait neuroticism. Daily negative affect was measured with the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Participants were asked to select from a 5-point scale for each of the 10 negative affect items, examples of which include “irritable” and “distressed.” Internal consistency reliability assessed on Day 1 was high (Cronbach's α = .85). The sum of the 10 items was used as an indicator of negative affect, with higher values indicating more of the construct. Ten items from the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) were modified to assess the degree to which participants experienced daily life as stressful. Items such as “Today, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?” and “Today, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?” were accompanied by a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Higher values indicated greater perceived stress. Internal consistency reliability assessed on Day 1 was high (Cronbach's α = .89). Daily data were collected over 56 days, with 1-, 2-, and 3-week packets counterbalanced within and between subjects. Neuroticism was assessed with a subscale of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1991). The 12 items were scored such that higher values indicated higher levels of neuroticism. Internal consistency reliability was high (Cronbach's α = .88).

The negative affect and stress time series for each individual were modeled with the reservoir model. Only individuals who completed at least half of the 56 daily observations were analyzed. The minimum possible value on each scale was subtracted from each response at each time, thereby setting the minimum possible value for all measurements to 0. Each series was analyzed with two to 10 latent classes and 11 starting values for β equally spaced from 0 to −1; the solution producing the minimum AIC was selected as the best solution. Full information maximum likelihood was used to handle missing data. The trait neuroticism for each subject was predicted with each of the four estimates produced for each subject via the reservoir model: β and μinput for each of the two time series (stress, negative affect).

One modification to the analysis was made relative to the simulation presented earlier. It was observed that initially a large percentage of results did not converge. By rescaling the time series by dividing by the standard deviation of the time series, which had the effect of rescaling the variances in the model, a substantially larger number of time series converged. Multiplication or division by a constant will not change estimates of the dissipation parameter β, but will change estimates related to the input distribution (i.e., μinput and σinput). Division of the time series by the standard deviation will result in the values of μc to be divided by this same constant. To return estimates of the input distribution to the original metric, one will have to apply the inverse of the constant to the values of μc; if one divides the original time series by its standard deviation, one will have to multiply the values of μc by the standard deviation of the original time series before applying Equations 8 and 9.

Results and Discussion

Tables 1 and 2 shows summary statistics for the reservoir model estimates and the results from the four regressions predicting neuroticism; standardized scores (z scores) were used for neuroticism in the analyses. There were 54 subjects with more than 50% of the daily stress self-reports and 53 subjects with more than 50% of the daily negative affect self-reports. The results do not suggest a relationship between the stress estimates and neuroticism, although the null results could be due to the relatively small sample size.

Table 1. Summary Statistics for Reservoir Estimates.

| Estimate | M | SD | Mdn | [Q1, Q3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β stress | −0.70 | 0.52 | −0.48 | [−0.91, −0.28] |

| μinput stress | 3.20 | 1.97 | 2.96 | [1.50, 4.40] |

| β negative affect | −1.54 | 1.01 | −1.98 | [−2.00, −0.79] |

| μinput negative affect | 1.21 | 1.17 | 0.82 | [0.31, 1.86] |

Note. Q1 = first quartile; Q3 = third quartile.

Table 2. Summary Statistics for Regression Results.

| Predictor | Intercept | Slope | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | p | |

| β stress | 0.12 | [−0.26, 0.50] | 0.19 | [−0.18, 0.56] | .32 |

| μinput stress | −0.24 | [−0.73, 0.25] | 0.07 | [−0.06, 0.20] | .26 |

| β negative affect | 0.40 | [−0.11, 0.91] | 0.29 | [0.01, 0.56] | .04 |

| μinput negative affect | −0.37 | [−0.76, 0.03] | 0.26 | [0.03, 0.50] | .03 |

Note. The trait of neuroticism was converted to z scores before analysis. CI = confidence interval.

With regard to negative affect, the results suggest a positive relationship between negative affect dissipation (β) and neuroticism (p = .04). Keeping in mind that dissipation parameters are negative, with values near 0 suggesting a low dissipation rate, the results suggest that individuals who have difficultly dissipating negative affect events are likely to have higher scores on the neuroticism measure. Individuals at the first quartile of β have an estimated z score on neuroticism of −.18, whereas individuals at the third quartile of β have an estimated z score on neuroticism of .17. The neuroticism and β relationship has an approximately medium effect size (r2 = .08). The results also suggest a positive relationship between μinput for negative affect and neuroticism (p = .03)—individuals perceiving more negative affect inputs tend to have higher neuroticism scores. Individuals at the first quartile of μinput have an estimated z score on neuroticism of −.29, whereas individuals at the third quartile of μinput have an estimated z score on neuroticism of .11. The neuroticism and μinput relationship has an approximately medium effect size (r2 = .09).

One may wonder to what degree the reservoir model estimates are correlated with one another. Table 3 presents the correlations of neuroticism and the four reservoir model estimates. These results suggest a high correlation between the β and μinput for stress (r = −.76), but a much lower correlation between the reservoir estimates for negative affect (r = −.26), suggesting that β and μinput are likely to be correlated in practice but not necessarily highly correlated. Interestingly, there may be similarities in the dissipation parameters across subjects (r = .24), perhaps pointing to a common construct such as resiliency.

Table 3. Correlations Between Neuroticism and Reservoir Estimates.

| Estimate | Neuroticism | Stress | Negative affect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| β | μinput | β | μinput | ||

| Neuroticism | 1.000 | ||||

| β stress | .140 | 1.000 | |||

| μinput stess | .156 | −.760 | 1.000 | ||

| β negative affect | .285 | .243 | −.099 | 1.000 | |

| μinput negative affect | .301 | .033 | .156 | −.257 | 1.000 |

To examine whether the reservoir estimates explain nonoverlapping pieces of variance in neuroticism, the four estimates were all used to predict neuroticism simultaneously (see Table 4). The p values for all four predictors were all below or near .05; in many classic multicollinearity examples, individual predictors become nonsignificant when simultaneously entered into a model. The four predictors explained 36.7% of the variance in neuroticism ( ); dropping any one predictor resulted in a drop of at least .055 in the r2 (.044 in the ). With the p values' drop in variance following the removal of any one predictor, and the combined variance being much larger than any one predictor, all seem to suggest that the reservoir model estimates may explain nonoverlapping pieces of variance in neuroticism despite some of the large correlations between reservoir estimates.

Table 4. Regression Results From Predicting Neuroticism Using All Reservoir Estimates.

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.04 | 0.28 | [−0.60, 0.52] | .894 |

| β stress | 1.07 | 0.34 | [0.38, 1.77] | .003 |

| μinput stess | 0.27 | 0.09 | [0.09, 0.45] | .004 |

| β negative affect | 0.26 | 0.13 | [0.003, 0.52] | .048 |

| μinput negative affect | 0.22 | 0.11 | [−0.002, 0.44] | .052 |

Note. The trait of neuroticism was converted to z scores before analysis. CI = confidence interval.

Researchers using reservoir model estimates in their models should consider a few issues raised by this example. First, one should note that the values of β on negative affect are particularly large. One way to understand the practical difference in β is using half-life; half-life is the time it takes for the level of something (e.g., stress) to decrease by half (see Footnote 4 regarding the calculation of half-life). The mean β for stress and for negative affect reflect half-lives of 0.99 days and 0.45, days respectively. This suggests that within about 1 day the effect of a stress event drops by half, and within about a half day the effect of a negative affect event drops by half; over the course of a full day a negative affect event may decrease to only 20% (0.452) of its original magnitude. The estimates for negative affect suggest relatively rapid recovery from every-day negative affect events; more frequent measurements may be required to get better estimates of negative affect dissipation. Figures 8C and 8D show the estimated distribution of inputs for negative affect and stress across individuals;7 these figures give some visual impression as to how the input distributions for negative affect and stress differ.

The estimates for negative affect β also produced a large number of individuals who had estimates approximately equal to −2. With data that take on integer-only values, this value is expected (see Appendix B) when a stressor (e.g., xt = 10) is followed by a minimum score (xt + 1 = 0). It was observed that individuals with many positive stress values followed by a value of 0 the next day produced β estimates of approximately −2. This suggests that these individuals have dissipation parameters less than −2, but that more frequent measurements are required to capture their handling of negative affect events; alternatively, finding ways to estimate lower bound values more precisely (distinguishing a score of 0 vs. 0.1) may be required to precisely estimate negative affect dissipation over a daily time scale for many individuals.

Conclusions

Differential equation models are a promising way to describe the relationships between a person's current state and how that person is changing. Although the pendulum model is a differential equation model that has been frequently used in psychology, it may do a poor job describing constructs that show floor effects, such as stress and negative affect. The reservoir model offers another way to model such time series. Rather than approach change over time as self-regulation around some nonzero equilibrium, the reservoir model treats constructs as if current levels were the sum of inputs and outputs—much like the input and output of liquid into a reservoir. The height of the liquid corresponds to the self-reports that participants make about the level of a construct (e.g., the number of life events or the level of arousal associated with an emotion). The implementation of the reservoir model presented here makes use of a combination of LDE and LDM: LDE has been used for the estimation of differential equation models, whereas LDM has been used to estimate nonnormally distributed latent variables. By observing over a single time series the dissipation parameter β, and mean and variance of the latent inputs (μinput and , respectively), reasonable estimates can be recovered as long as the occurrence of large inputs is not (on average) more frequent than the span over which derivatives are estimated.

There are several assumptions that should be addressed with regard to the model and how it was implemented. First and foremost are two theoretical assumptions. As mentioned in the introduction, it is possible that the observation of older adults with and without significant floor effects could indicate different populations; as we are not aware of theory that would posit the existence of two discrete populations, we have assumed that all subjects are representative of a single population. More critically, the reservoir model treats inputs and outputs as additive—a large increase in stress is due to the perception of a large stressor. Being a linear model, the reservoir model may be less adept at nonproportional responses (i.e., straw that breaks the camel's back); such responses may be better described with a nonlinear model (S. M. Boker, personal communication, June, 4, 2010). The current model also posits instantaneous inputs (event occurs) followed by a dissipation rate related to the height of the construct. It is possible that these in fact should be swapped, such that inputs exponentially increase and then discrete events occur that reduce the height of the liquid (e.g., actions taken to reduce stress). The reservoir model is one very specific formulation of change meant to expand researchers' options beyond the pendulum model, but many variations of this model are possible, and the choice of models is a function of relevant theory and the process of interest.

Aside from the theoretical assumptions, there are assumptions inherent to how the reservoir model was applied in this article. The current presentation and the code provided in Appendix A assume equally spaced observations, although this assumption could be relaxed. The code provided in Appendix A is also written for an embedding dimension of 2, to use latent classes of two to 10, and to use 11 starting values of β. All these conditions can be modified. The current article has also assumed time series of moderate length (25–100 observations);8 given the increasing bias observed with shorter time series, we believe it may not be advisable to use time series much shorter than this range to produce individual-level reservoir model estimates. It should be noted that when estimating individual-level parameters, the standard errors of the estimates for an individual are suspect; the embedded matrix consists of copies of the same information that violates the structural equation model assumption of independent observations (rows) and furthermore suggests more degrees of freedom than are present in the data. To our knowledge, standard errors have not been derived for applications using an embedded matrix with a single time series, but research suggests that these standard errors produced by SEM software may be too large (von Oertzen & Boker, 2010); bias in other dynamic models has also been observed (Chow, Ho, Hamaker, & Dolan, 2010; Zhang, Hamaker, & Nesselroade, 2008). To produce correct standard errors, researchers could alternatively collect short time series from across a large number of subjects (e.g., four observations on 50 subjects). Such data could be modeled if one were willing to assume a common dissipation parameter and input distribution across one or more groups of subjects.

The current presentation has also focused on modeling one time series; modifications to the presented model could allow multiple indicators of the same construct to be used to estimate the derivatives (Boker et al., 2004), or to include exogenous measures of inputs and outputs. In addition, no distributional shape was assumed for the inputs in this article; the input distribution was only required to consist of positive values. One could, however, specify a distributional shape using LDM (see Markon & Krueger, 2006a, 2006b, for examples).

The intriguing possibilities presented by the reservoir model parameters are demonstrated in the applied example. There are many mathematical forms that could be used to describe time series, but it is the applied example that suggests that the reservoir model parameters may be related to other known constructs and are therefore informative about the differences between individuals. This model may be useful for distinguishing how traits are differentially related to the inputs and outputs of constructs. This model may also be able to help researchers tap into differences in how individuals change over time. By understanding these differences, we can hope to understand the characteristics of the individuals who seem most adept at navigating the events of daily life and perhaps learn how to imitate those characteristics.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A.

Reservoir Model Code

The following code is written for the statistical program R (R Development Core Team, 2012) with the package OpenMx (Boker et al., 2011). The OpenMx package is currently available online (http://openmx.psyc.virginia.edu). The following code allows the user to input the time series from a single individual ( YourTimeSeries). The code will embed this data, set up the reservoir model, fit the model using a range of starting values, and returns the model that produces the maximum likelihood. The user interacts with the function Fitreservoir() that will call the other functions. The user will find that it is sometimes necessary to rescale a time series (e.g., divide/multiplying by two) to fit the reservoir model. The time series can be divided by the standard deviation with the option StDev = TRUE.

The code makes several assumptions. First, it assumes that one is working with equally spaced observations. It is also assumed that the minimum possible value on the time series scale is set equal to 0. The model and starting values in the program are the same as described in the Application to Data section of this article. This code does not assume complete data; missing data can be included in time series with the missing data character NA. Updated versions and modifications of this code will be maintained on the web page of the first author.

library(OpenMx)

ReservoirModel < - function(TimeSeries,BetaStart,MeanVal,ProbVal,Nclass,EmbedDim=2)

{

#Define the names of the observed and latent variables

ObsVar < - names < - paste(“x”,c(1:EmbedDim),sep= “”)

LntVar <- c(“X”,“dX”)

MatNames <- c(ObsVar,LntVar)

#Embed the Time Series

Data <- TimeSeries[1:(length(TimeSeries)-(EmbedDim)+ 1)]

for(i in 2:EmbedDim) { Data <- cbind(Data,TimeSeries[i:(length(TimeSeries)-EmbedDim + i)]) }

colnames(Data) <- names

#Calculate loadings for latent derivatives

L <- cbind(rep(1,EmbedDim),c(1:EmbedDim)-mean(c(1:EmbedDim)))

#Setup OpenMx matrix of Asymetric (single-headed arrow) relationships

A < - mxMatrix(type=“Full”,nrow=length(MatNames),ncol = length(MatNames),free = FALSE,name= “A”)

A@values[(which(MatNames = = “x1”) +0):(which(MatNames = = “x1”) +EmbedDim-1),

which(MatNames = = “X”):(which(MatNames = = “X”) + 1)] <- L

A@labels[which(MatNames==“dX”),which(MatNames==“X”)] <- “Beta”

A@values[which(MatNames==“dX”),which(MatNames==“X”)] <- BetaStart

A@free[which(MatNames = = “dX”),which(MatNames = = “X”)] <- TRUE

#Setup OpenMx matrix of Symetric (double-headed arrow) relationships

S <- mxMatrix(type=“Symm”,nrow=length(MatNames),ncol = length(MatNames),free = FALSE,name= “S”)

diag(S@labels) < - c(paste(“eObs”,c(1:length(ObsVar)),sep = “”),“eX”,“edX”)

diag(S@free) <- TRUE; diag(S@lbound) <- 0

#Setup up OpenMx Mean matrix with parts common to all classes

M < - mxMatrix(“Full”,ncol = 1,nrow=length(MatNames),free = c(rep(FALSE,EmbedDim),TRUE,TRUE),name=“M”)

M@labels[1:(EmbedDim+1)] < - c(paste(“E”,c(1:EmbedDim),“mean”,sep = “”),“meanX”)

#Setup an Identity and Filter matrix, needed for expected mean and covariance calculation

I <- mxMatrix(type=“Iden”,nrow=length(MatNames),name = “I”)

F <- mxMatrix(type=“Full”,nrow=length(ObsVar),ncol = length(MatNames),free=FALSE,name = “F”)

diag(F@values[,1:EmbedDim]) <- 1

#Create OpenMx objects for each class; there will be totalof these equal to Nclass.

for(i in Nclass:1) {

#Change mu_input for each class

M@values[which(MatNames = = “dX”)] <- MeanVal[i]

M@labels[which(MatNames = = “dX”)] < - paste(“meanDX”,i,sep= “”)

#Fix each mean to be larger than the mean of the previous class

MeanConstraint <- mxConstraint(NotWhatIWant>NotWhatIWantEither)

MeanConstraint@formula[2] <- parse(text = paste(“meanDX”,i,sep=“”))

MeanConstraint@formula[3] <- parse(text=paste(“meanDX”,i-1,sep=“”))

if(i = = 1) {

M@free[which(MatNames = = “dX”)] <- FALSE

MeanConstraint@formula[3] <- parse(text = “0”)

}

#Create a class names “Class#” with “#” replaced by a number. Include all required matrices

#(A, S, D, I, M), and tell OpenMx how to calculate the expected means and expected

#covariance.

assign(paste(“Class”,i,sep = “”),mxModel(paste(“Class”,i,sep = “”),A,S,F,I,M,MeanConstraint,

mxAlgebra(F%*%solve(I-A)%*%S%*%t(solve(I-A))%*%t(F),name= “ExpCov”,

dimnames=list(ObsVar,ObsVar)),

mxAlgebra(t(F%*%solve(I-A)%*%M),name = “ExpM”,

dimnames = list(NA,ObsVar)),

mxFIMLObjective(covariance = “ExpCov”, means = “ExpM”,vector=TRUE)))

}

#Begin collecting all of the model pieces into a single mxModel. The model is named, the data

#are identified, a matrix representing the probability of each class is created (bounded by

#0 and 1), and the sum of the probabilities is constrained to equal 1.

ReservoirModel <- mxModel(“ReservoirModel”, mxData(Data, type = “raw”),

mxMatrix(“Full”, name = “ClassProbabilities”, nrow = Nclass, ncol = 1,

free = rep(TRUE,Nclass),

labels = c(paste(“pclass”, 1:Nclass, sep=“”)),values = ProbVal),

mxBounds(c(paste(“pclass”, 1:Nclass, sep=“”)),0,1),

mxMatrix(“Iden”, nrow = 1, name = “constraintLHS”), mxAlgebra(sum(ClassProbabilities),

name = “constraintRHS”),

mxConstraint(constraintLHS == constraintRHS))

#Add each of the Class# objects to the mxModel named “ReservoirModel”.

for(i in 1:Nclass) {

ReservoirModel <- mxModel(ReservoirModel, get(paste(“Class”,i,sep = “”)))

}

#Create the formula required to calculate the total — 2*log-likelihood based on the

#probability of each class and the likelihood returned from each class. The large number

#of lines are required to be able to write an OpenMx formula dynamically for any number of

#classes.

Formula <- “sum(log(pclass1%x%Class1.objective“

for(i in 2:Nclass) {

Formula <- paste(Formula, “ + ”, “pclass”,i,“%x%Class”,i,“.objective”,sep= “”) }

Formula <- paste(Formula,“))”,sep = “”)

lcaAlgebra <- mxAlgebra(-2*sum(),name = “lca”)

lcaAlgebra@formula[3] <- parse(text=Formula)

if(Nclass = = 1) { lcaAlgebra <- mxAlgebra(-2*sum(log(pclass1%x%Class1.objective)),name= “lca”)

}

#Add the formula for calculating the total —2*log-likelihood to the model.

ReservoirModel <- mxModel(ReservoirModel, lcaAlgebra, mxAlgebraObjective(“lca”))

#Run the model and return the results

return(mxRun(ReservoirModel))

}

FitReservoirModel <- function(x,StDev = FALSE) {

#Embed TimeSeries and calculate intial drivative estimates using GOLD.

#These will be used for estimating the maximum mu_input for a given initial beta.

if(StDev) { StDev <- sd(x,na.rm = TRUE); x <- x/StDev }

y <- cbind(x[1:(length(x)-1)],x[2:length(x)])%*%matrix(c(.5,.5),nrow=2)

dy <- cbind(x[1:(length(x)-1)],x[2:length(x)])%*%matrix(c(-1,1),nrow=2)

#Set up a matrix of starting conditions—varying latent classes and betas.

Conditions <- cbind(rep(seq(-1.0,0,0.1),9),rep(c(2:10),each=11))

#A place to store results including — 2*Log-Likelihood and AIC

Results <- matrix(NA,dim(Conditions)[1],3)

#Step through each row of the Conditions matrix

for(i in 1:dim(Conditions)[1]) {

#For a set of conditions, set the number of classes, initial value of beta, calculate

#the maximum mu_input given the intial beta, and create a sequence for mu_input

#from zero to the maximum value.

Nclass <- Conditions[i,2]

InitialSlope <- Conditions[i,1]

MaxMu <- max(dy+(-y*InitialSlope),na.rm=TRUE)

MeanVal <- seq(0,MaxMu,length.out=Nclass)

#Run the model for this set of conditions

out1 <- try(ReservoirModel(x,InitialSlope,MeanVal,rep(1,Nclass)/Nclass,Nclass),silent=TRUE)

#If we get a valid output, save the −2 Log-Likelihood, convergence status, AIC

if(mode(out1) = = “S4”) { Results[i,] <- c(out1@output$Minus,out1@output$status[[1]],

summary(out1)$informationCriteria[1,2]) }

}

#Find the best set of Conditions, and set up intial conditions for that result.

Best <- which((Results[,3] ==min(Results[,3],na.rm=TRUE))&(Results[,2] <=1))

if(length(Best) = = 0) { return(cat(“\nError: No solutions converged.\n\n”)) }

if((sum(Results[,2] < = 1,na.rm=TRUE)/dim(Conditions)[1]) <0.5) {

cat(“\nCaution: Less than 50% of conditions converged.\n\n”) }

Nclass <- Conditions[Best,2]; InitialSlope <- Conditions[Best,1]

MaxMu <- max(dy+(-y*InitialSlope),na.rm=TRUE); MeanVal <- seq(0,MaxMu,length.out=Nclass)

#Rerun the conditions producing the best result, and return the full OpenMx results

return(list(Model =ReservoirModel(x,InitialSlope,MeanVal,rep(1,Nclass)/Nclass,Nclass),

StDev=StDev))

}

output <- FitReservoirModel(YourTimeSeries)

summary(output$Model)

Appendix B.

Expected Value of P

It is expected that estimates of β = −2 will occur when a stressor (e.g., xt = 10) is followed by a minimum score (xt+1 = 0), and little or no additional input (μinput = 0).

Given Equations 3 and 6, then

Substituting values, and replacing the equation for change (dx/dt),

| (B1) |

Solving Equation B1,

| (B2) |

Regardless of the true rate of dissipation, subjects with a large number of inputs followed by scale scores of 0, are more likely to produce β values equal to −2.

Footnotes

Although we primarily focus on a floor effect, the model could also be used in the description of observations demonstrating a ceiling effect. For example, the buildup of some positive resources demonstrates ceiling effects, and events that occur remove from those resources, thereby perturbing an individual's construct away from the ceiling (reduction in resources).

As individuals may differ in their dynamics (Molenaar, 2004), we have opted to focus on the estimation of parameters for each individual's time series; consequently times series of approximately 25 measurements or more are likely required. Substantially shorter time series (e.g., four observations) could be used with this analysis if one were willing to assume that a group of individuals all possessed the same dynamics. It would not be possible to estimate individual parameters in such a case, but it would be possible to contrast two or more distinct groups (e.g., intervention and control groups) provided a reasonable sample was available for each of the groups (e.g., 25–100 individuals per group).

This relationship can be demonstrated by solving Bernoulli's equation. In a physical reservoir the rate of liquid reduction would be proportional to the square root of the height of the liquid. Due to the difficulty of modeling the square root of latent variables, in this article we will implement a model that uses a relationship in which the rate of height reduction is proportional to the height of the liquid.

The half-life can be calculated as t1/2 = ln (2)/– β, in which ln indicates the natural log.

The setting of values less than 0 to 0 produces a misspecification between the simulated time series and the model being applied. The misspecification is greatest when there are a large number of values near 0 (low input frequency, large dissipation parameter), as these are the values most likely to be perturbed below 0 with the addition of measurement error. In the most extreme condition (input frequency of 12.5%, β = −.9), approximately 36% of values fell below 0; this produced a bias in the mean, variance, and lag-1 autocorrelation of +25%, −11%, and +1%, respectively. The typical effect of the misspecification was much smaller. Across conditions the median percentage of values below 0 was 10%. The median bias in the mean, variance, and lag-1 autocorrelation was +2%, −5%, and +0.1%, respectively, suggesting that values being set equal to 0 are typically relatively small. Some improvement in parameter estimates should be possible by taking into account the misspecification.

Examination of the results indicated that the best fitting solution typically occurred with five or fewer classes (83.6% of 162,000 time series). For a small percentage of time series (1.6%), the best solution was eight classes.

These figures were estimated from the individual reservoir model results with the estimate probabilities for each class to estimate the number of observations corresponding to each class (pc × n, where n is the number of observations); the observations were then equally distributed across a sequence of input values from the midpoints before and after the mean of the class ([μc + μc – 1]/2 and [μc + μc + 1]/2). Number of observations per input value were added up across individuals and divided by the total number of observations. Input value bins started at 0 and were incremented by 0.5; wider or narrowed bins have an effect similar to changing the width of histogram bars.

A small sample of time series with 1,000 observations was examined to evaluate parameter estimation as the number of observations increases. The general pattern of results appeared to match those of the time series with 100 observations, albeit with narrower confidence intervals.

Updates and modifications to the code provided will be maintained by Pascal R. Deboeck. The simulations were made possible by the Center for Research Methods and Data Analysis, University of Kansas. We would like to thank Stephen Tueller and Mignon Montpetit for their insight and comments on this article.

Contributor Information

Pascal R. Deboeck, Department of Psychology, University of Kansas

C. S. Bergeman, Department of Psychology, University of Notre Dame

References

- Bisconti TL, Bergeman CS, Boker SM. Social support as a predictor of variability: An examination of the adjustment trajectories of recent widows. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21(3):590–599. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boker SM, Graham J. A dynamical systems analysis of adolescent substance abuse. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1998;33(4):479–507. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3304_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boker SM, Laurenceau JP. Dynamical systems modeling: An application to the regulation of intimacy and disclosure in marriage. In: Walls TA, Schafer JL, editors. Models for intensive longitudinal data. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Boker SM, Leibenluft E, Deboeck PR, Virk G, Postolache TT. Mood oscillations and coupling between mood and weather in patients with rapid cycling bipolar disorder. International Journal of Child Health and Human Development. 2008;1(2):181–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boker S, Neale M, Maes H, Wilde M, Spiegel M, Brick T, et al. Fox J. OpenMx: An open source extended structural equation modeling framework. Psychometrika. 2011;76(2):306–317. doi: 10.1007/s11336-010-9200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boker SM, Neale MC, Rausch JR. Latent differential equation modeling with multivariate multi-occasion indicators. In: Montfort KV, Oud J, Satorra A, editors. Recent developments on structural equation models: Theory and applications. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic; 2004. pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Boker SM, Nesselroade JR. A method for modeling the intrinsic dynamics of intraindividual variability: Recovering the parameters of simulated oscillators in multi-wave panel data. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2002;37(1):127–160. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3701_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow SM, Ho MR, Hamaker EJ, Dolan CV. Equivalences and differences between structural equation and state-space modeling frameworks. Structural Equation Modeling. 2010;17(2):303–332. doi: 10.1080/10705511003661553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chow SM, Ram N, Boker SM, Fujita F, Clore G. Emotion as a thermostat: Representing emotion regulation using a damped oscillator model. Emotion. 2005;5(2):208–225. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI–R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Deboeck PR. Estimating dynamical systems: Derivative estimation hints from Sir Ronald A. Fisher. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2010;45(4):725–745. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2010.498294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deboeck PR, Montpetit MA, Bergeman CS, Boker SM. Describing intraindividual variability at multiple time scales using derivative estimates. Psychological Methods. 2009;14(4):367–386. doi: 10.1037/a0016622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delsing MJMH, Oud JHL. Analyzing reciprocal relationships by means of the continuous-time autoregressive latent trajectory model. Statistica Neerlandica. 2008;62(1):58–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9574.2007.00386.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan CV, van der Maas H. Fitting multivariage normal finite mixtures subject to structural equation modeling. Psychometrika. 1998;63(3):227–253. doi: 10.1007/BF02294853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin J, Koopman SJ. Time series analysis by state space methods. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]