Abstract.

The number of new syphilis cases in Brazil has risen alarmingly in recent years. However, there is limited data regarding syphilis prevalence in the Brazilian prison population. To facilitate the development of effective interventions, a cross-sectional study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of Treponema pallidum infection, active syphilis, and associated risk factors among Brazilian prisoners. We administered a questionnaire to a population-based sample of prisoners from 12 prisons in Central-West Brazil and collected sera for syphilis testing, from January to December 2013. Univariable and multivariable regression analyses were performed to assess associations with active syphilis. We recruited 3,363 prisoners (men: 84.6%; women: 15.4%). The overall lifetime and active syphilis prevalences were 10.5% (9.4% among men; 17% among women, P < 0.001) and 3.8% (2% among men; 9% among women, P < 0.001), respectively. The variables associated with active syphilis in men prisoners were homosexual preference, history of sexually transmitted infections, and human immunodeficiency virus status. Among women, the factors were sex with intravenous drug users, genital ulcer disease, and previous incarceration. Despite the high prevalence of active syphilis, 88.5% reported unawareness of their serological status and 67% reported unprotected sexual practices. Women had the highest rates of infection, including them in a high-risk group for the development of syphilis during pregnancy. Thus, implementing screening programs to enable continuous measures of control and prevention of T. pallidum infection in the prison environment, mainly in women institutions, is important to prevent severe forms of this disease and congenital infections.

INTRODUCTION

Syphilis is a chronic multistage disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum and is usually transmitted by sexual contact or through the placenta during pregnancy.1 Syphilis infection remains an alarming public health problem worldwide, with an estimated 36 million prevalent cases globally and more than 12 million incident cases annually.2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than half the pregnant women with active syphilis will have a stillbirth, perinatal death, or serious neonatal infection.3 Syphilis has become one of the top five most reported infectious diseases and the most frequently reported sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in Brazil. Estimates of new sexual transmission in the adult population are 937,000 cases each year, with a prevalence of 2.6%, varying from 1.0% to 4.4%.2,4

Despite the existence of inexpensive and effective antimicrobial therapy, syphilis has increased significantly in vulnerable groups, including men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women (TW), commercial sex workers (CSWs), and prisoners.5–8 Prison populations are considered to be at high risk for STIs, including syphilis, due to risk behaviors such as intravenous drug use, homosexual contact with unprotected sexual practices, and multiple sexual partners.8,9

Although syphilis control strategies are well established, some studies have shown significantly increasing rates of T. pallidum infection among prisoners.10–12 The high prevalence of syphilis may contribute to T. pallidum transmission among prisoners, as well as the general population, especially due to unprotected sexual practices.10,11,13 Furthermore, syphilis has been considered one of the factors that facilitate human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission, at the same way HIV may facilitate a rapid progression of syphilis to advanced stages.14 To control this important public health problem, the implementation of standard infection control practices, such as serological screening in the correctional setting, is needed to diagnosis prevalent disease and prevent onward transmission.10,13

Brazil has the fourth largest prison population in the world, with 607,700 persons in penal institutions and the state of Mato Grosso do Sul has the highest rate of incarceration.12 However, the prevalence rates of syphilis in Brazilian prisons remain largely unknown so that the assessment of the sources of T. pallidum transmission in prisoners could facilitate decision-making regarding how to screen, prevent further spread, and provide appropriate care for infected prisoners.15 To better understand these features, a multicenter cross-sectional study was undertaken in 12 prisons in Central-West Brazil, to propose future prevention strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting.

Mato Grosso do Sul is a state in Central-West Brazil, which borders Paraguay and Bolivia. With a population of 2.5 million people, it has the highest rate of incarceration in the country, with 568.9 per 100,000 habitants incarcerated, predominantly due to drug-trafficking crimes.12 There were 15,513 prisoners in the state in 2014, distributed among 44 penal institutions,15 with a total of 9,913 prisoners in 23 penal institutions in the “closed” system (greater-risk offenders).12 Twelve closed prisons in the five largest cities in the state (Campo Grande, Corumbá, Dourados, Ponta Porã, and Três Lagoas) were included in a cross-sectional study performed from January 2013 to December 2013, with 7,221 prisoners representing 73% of the closed system and 59% of the total prison population in the state. Out of those prisons, there were eight men prisons (6,552 prisoners) and four women prisons (669 prisoners).

Study population.

Proportional stratified sampling was performed using each prison as a unit of randomization. On the data collection day, the prisoners were listed in numerical order, and a list of random numbers was generated using Epi-Info 6.04 software (Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA). The sample size was calculated using a prevalence of 3% for lifetime syphilis with a variation of 1%,4 a power of 80% and an alpha-type error of 5%. We added 20% more individuals from each prison to account for anticipated loss due to refusal to participate. Prisoners who were 18 years of age or more and who consented to participate were included in the study.16

Data and blood collection.

Each participant underwent an interview utilizing a standardized questionnaire. The variables obtained during the interview included age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, drug use, sexual history, STIs, blood transfusion, tattoos, piercings, previous surgery and incarceration, time served, self-reported mental illness, and genital ulcer disease. The participant’s race/skin color (white, black, indigenous, Asian, or mixed), gender, and sex were self-reported. After appropriate antisepsis, 10 mL of peripheral venous blood sample was obtained using a vacuum tube system, processed to obtain the serum, and stored at −20°C for the serological assays.

Serological testing.

The prevalence of lifetime syphilis was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (ICE*Syphilis, DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy) following the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay detects antibodies against T. pallidum using recombinant proteins (TpN15, TpN17, and TpN47).17 ELISA-reactive samples were serially diluted to quantify titers of syphilis anti-cardiolipin antibodies by Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test (Abbott Murex, Dartford, UK). Active syphilis was defined as a VDRL ≥ 1:818 as recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.

Statistical analysis.

Questionnaire-based data and biological testing results were recorded, double checked, and entered into the online database Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to analyze the univariate and multivariate models. The prevalence of T. pallidum lifetime and active syphilis was expressed as the percentage among prisoners screened, with cluster-adjusted 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Dichotomized and categorical data were analyzed with the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. For continuous variables, the t test or analysis of variance was used. Univariate analysis was performed to verify the associations between the dependent and independent variables. Those achieving a prespecified level of significance (P < 0.05) were included in the multivariable analysis. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the crude odds ratios and adjusted odds ratio (AOR).

Ethical approval.

This study was conducted with the approval of the research ethics committee at the Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (no. 191.877). All eligible participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. The results of the serological tests were reported directly to the prisoners by an infectious disease physician and the prisoners were referred for specialist treatment.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic factors and risk behaviors.

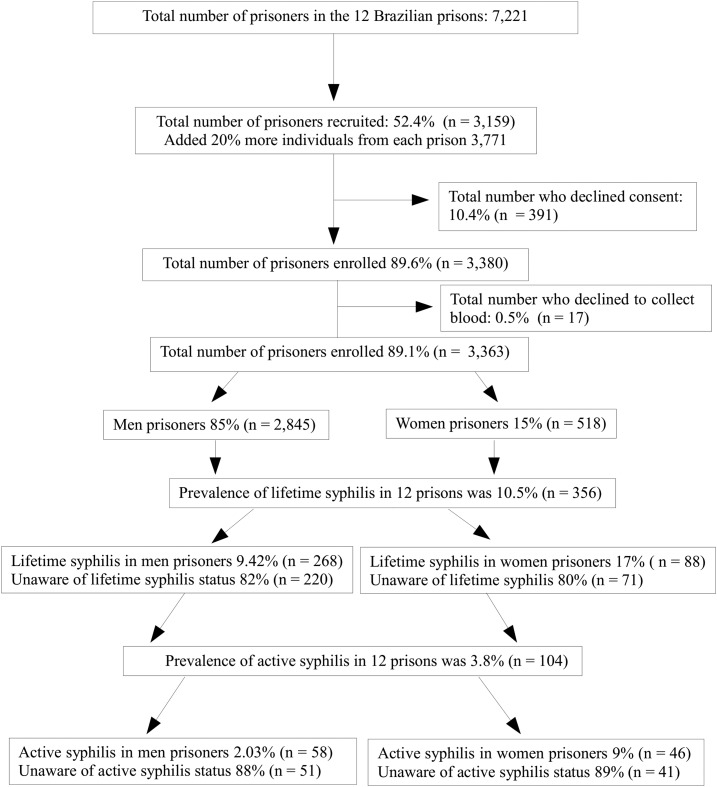

Out of the 3,771 individuals invited to participate, 3,363 (89.1%) agreed to the interview and provided blood samples (Figure 1). There were no differences among prisoners who agreed to participate and those who refused to join the study. Sociodemographic characteristics, risk behaviors, and prevalence results stratified by sex are shown in Table 1. Nearly, 84.6% of participants were men (2,845) and the mean age was 32 years (range: 18–80 years). The majority of these individuals were from the state of Mato Grosso do Sul (64%) and reported marital status as single (44%) (P ≤ 0.01). The prisoners self-reported racial groups included white (33%), mixed (50%), black (13%), Asian (2%), and indigenous (1%). Approximately, 45% reported being illiterate. Differences between men and women groups were noted for almost all variables, highlighting the importance of analyzing these groups separately. In this study, 54% men and 38% women prisoners were using drugs (P ≤ 0.01). The prisoners have intimate visits weekly and sex with multiple partners was reported by 49% (N = 1,414) of men and 53% (N = 277) of women (P ≤ 0.01). Homosexual preference was identified in 2% (N = 48) of men and 11% (N = 58) of women (P ≤ 0.01), sex with an intravenous drug user (IDU) was reported by 3% (N = 82) of men and 6% (N = 30) women (P ≤ 0.01), HIV-positive status was affirmed by 1.6% (N = 45) men and 1.9% (N = 10) women (P = 0.56), genital ulcer diseases were reported by 2.2% of men (N = 64) and 2.1% (N = 11) women (P = 0.85). In both groups, 67% (N = 2,242) reported irregular condom use and 12% (N = 393) reported history of STIs. Previous incarceration was observed in 59% (62% men and 40% women, P = 0.01) and the mean time in prison was 20 ± 27 months for men and 12 ± 12 months for women (P ≤ 0.01) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the screening process for detection of lifetime and active syphilis.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, risk behaviors and prevalence results stratified by sex in 12 Brazilian prisons (N = 3,363)

| Sex, N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Man, N = 2,845 | Women, N = 518 | P value |

| Lifetime syphilis | 268/2,845 (9.4) | 88/518 (17) | < 0.01 |

| Active syphilis | 58/2,845 (2) | 46/518 (9) | < 0.01 |

| Sociodemographic | |||

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 32 ± 10 | 32 ± 10 | 0.36 |

| Old age and stable sexual partner | 156/2,845 (5) | 49/518 (9) | < 0.01 |

| Low income | 393/2,845 (14) | 71/518 (14) | 0.94 |

| Marital status, single | 1,522/2,840 (53) | 332/506 (65) | < 0.01 |

| Ethnicity | < 0.01 | ||

| White | 912/2,747 (33) | 137/470 (29) | |

| Mixed | 1,366/2,747 (50) | 283/470 (60) | |

| Black | 370/2,747 (13) | 34/470 (7) | |

| Indigenous | 37/2,747 (1) | 4/470 (1) | |

| Asian | 62/2,747 (2) | 12/470 (2) | |

| Reside in MS | 1,889/2,845 (66) | 277/518 (53) | < 0.01 |

| Illiterate | 1,195/2,749 (43) | 282/514 (55) | < 0.01 |

| Drug history | |||

| Drug use over the last year | 1,543/2,845 (54) | 199/518 (38) | < 0.01 |

| IDU over the last year | 26/2,769 (1) | 5/503 (1) | 0.90 |

| Ever shared needles/syringes | 79/2,845 (3) | 28/516 (5) | 0.49 |

| Sexual history | |||

| Sexual preference, homosexual | 48/2,845 (2) | 58/509 (11) | < 0.01 |

| Previously had homosexual intercourse | 154/2,782 (5) | 125/474 (26) | < 0.01 |

| Sex with a drug use | 958/2,845 (34) | 256/516 (50) | < 0.01 |

| Sex with an IDU | 82/2,642 (3) | 30/494 (6) | < 0.01 |

| No stable partner (more than five in last year) | 1,414/2,845 (49) | 277/518 (53) | < 0.01 |

| Sexual partner with HIV, hepatitis or syphilis | 90/2,828 (3) | 33/515 (6) | < 0.01 |

| HIV positive | 44/2,845 (1.6) | 10/518 (1.9) | 0.56 |

| Urethral discharge | 129/2,811 (4.5) | 177/497 (35.6) | < 0.01 |

| Warts in the genital region | 87/2,837 (3) | 21/515 (4) | 0.23 |

| Genital ulcer disease | 64/2,838 (2.2) | 11/517 (2.1) | 0.85 |

| Condom use | 0.35 | ||

| Always | 959/2,845 (34) | 162/513 (31) | |

| Sometimes/never | 1,891/2,845 (66) | 351/513 (68) | |

| Other risk behavior | |||

| History of STI(s) | 342/2,703 (13) | 51/508 (10) | 0.09 |

| Blood transfusion | 353/2,811 (12) | 59/516 (11) | 0.47 |

| Tattoos | 1,915/2,845 (67) | 324/518 (62) | 0.03 |

| Piercings | 192/2,821 (7) | 186/517 (36) | 0.01 |

| Shared objects | 1,026/2,845 (36) | 268/518 (52) | 0.01 |

| Surgery | 1,119/2,840 (39) | 328/515 (64) | 0.01 |

| Mental illness | 1,150/2,766 (41) | 271/517 (52) | 0.01 |

| Prison | |||

| Previous incarceration | 1,758/2,836 (62) | 207/517 (40) | 0.01 |

| Time in prison, months, mean ± SD | 20 ± 27 | 12 ± 12 | < 0.01 |

| Reason for admission | < 0.01 | ||

| Drug trafficking | 1,142/2,360 (48) | 383/437 (88) | |

| Theft | 741/2,360 (31) | 30/437 (7) | |

| Homicide | 324/2,360 (14) | 14/437 (3) | |

| Sexual abuse | 64/2,360 (3) | 1/437 (0) | |

| Penal institution | |||

| EPFCAJG | 81/518 (16) | ||

| EPFTL | 76/518 (15) | ||

| EPFPP | 94/518 (18) | ||

| EPFIIZ | 268/518 (52) | ||

| EPC | 263/2,845 (9) | ||

| PTL | 263/2,845 (9) | ||

| EPRB | 252/2,845 (9) | ||

| CTAL | 116/2,853 (4) | ||

| PTCG | 286/2,845 (10) | ||

| IPCG | 517/2,845 (18) | ||

| EPJFC | 604/2,845 (21) | ||

| PHAC | 539/2,845 (19) | ||

CTAL = Centro de Triagem Anízio Lima; EPC = Estabelecimento Penal de Corumbá; EPFCAJG = Estabelecimento Penal Feminino Carlos Alberto Jonas Giordano; EPFIIZ = Estabelecimento Penal Feminino Irmã Irma Zorzi; EPFPP = Estabelecimento Penal Feminino de Ponta Porã; EPJFC = Estabelecimento Penal Jair Ferreira de Carvalho; EPFTL = Estabelecimento Penal Feminino de Três Lagoas; EPRB = Estabelecimento Penal Ricardo Brandão; IDU = intravenous drug user; IPCG = Instituto Penal de Campo Grande; PHAC = Penitenciária Harry Amorim Costa; PTL = Penitenciária de Três Lagoas; PTCG = Presídio de Transito de Campo Grande; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

The prevalence of lifetime syphilis was 9.4% (N = 268/2,845; 95% CI = 8.37–10.55) in man and 17% (N = 88/518; 95% CI = 13.85–20.50) in women prisoners. Active syphilis was 2% (N = 58/2,845; 95% CI = 1.55–2.62) in men and 9% (N = 46/518; 95% CI = 6.57–11.66) in women. All cases were reported to health-care services to provide appropriate therapy. In this study, 90% (N = 2,687) of interviewed prisoners reported unawareness of their serological status of STIs. Out of those, 88.5% (N = 92/104) had active syphilis (VDRL ≥ 1:8) (Figure 1). There were significant differences of lifetime and active syphilis among prisons. The highest prevalence of lifetime was 15.5% in the Female Criminal Establishment Irmã Irma Zorzi (EPFIIZ) and the lowest was 2.3% in the Female Penal Establishment Jonas Carlos Alberto Giordano (EPFCAJG) (P ≤ 0.01). For active syphilis, the highest prevalence was in EPFIIZ (13.7%) and the lowest was in EPFCAJG (1.2%) (P ≤ 0.01).

The multivariate analysis showed that homosexual preference (AOR = 4.51; 95% CI = 0.97–20.95), HIV infection (AOR = 3.70; 95% CI = 1.34–10.21), and history of STIs (AOR = 2.86; 95% CI = 1.30–6.31) were associated with active syphilis in men. Among women, the factors were sex with an IDU (AOR = 3.87; 95% CI = 1.40–10.64), history of genital ulcer disease (AOR = 13.49; 95% CI = 2.79–65.24), and previous incarceration (AOR = 2.23; 95% CI = 1.08–4.63) (Table 2). Older age (above sixty years old) was a protective factor to active syphilis in women (AOR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.93–0.99).

Table 2.

Multivariable regression analysis of risk factors associated with active syphilis among prisoners (N = 3,363)

| Men prisoners | Women prisoners | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | Crude OR | Adjusted OR |

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age, per year | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.94 (0.92–0.97) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | |

| Reside in MS | 1.08 (0.62–1.88) | |||

| Drug history | ||||

| Drug use | 1.82 (1.05–1.77) | 1.39 (0.76–2.56) | ||

| Intravenous drug use | 0.71 (0.42–1.20) | 0.40 (0.21–0.79) | ||

| Sexual history | ||||

| Homosexual preference | 3.51 (1.05–11.68) | 4.51 (0.97–20.95) | 1.49 (0.63–3.52) | |

| Previously had homosexual intercourse | 1.69 (0.66–4.32) | 1.50 (0.74–3.05) | ||

| Sex with a drug use | 1.37 (0.81–2.31) | 1.64 (0.88–3.05) | ||

| Sex with an IDU | 0.55 (0.07–4.09) | 3.42 (1.37–8.48) | 3.87 (1.40–10.64)* | |

| Fixed sexual partner | 0.62 (0.36–1.06) | 1.72 (0.93–3.19) | ||

| Sexual partner with HIV, hepatitis, or syphilis | 2.32 (0.82–6.57) | 3.15 (1.28–7.73) | ||

| HIV positive | 4.69 (2.05–10.71) | 3.70 (1.34–10.21)* | 2.64 (0.54–12.85) | |

| Irregular condom use | 0.85 (0.50–1.45) | 1.20 (0.60–2.41) | ||

| Urethral discharge | 1.55 (0.61–3.93) | 0.77 (0.40–1.47) | ||

| Warts in the genital region | 0.54 (0.07–3.94) | 1.75 (0.49–6.20) | ||

| Genital ulcer disease | 2.42 (0.73–7.97) | 6.34 (1.78–22.54) | 13.49 (2.79–65.24)* | |

| Other risk behavior | ||||

| History of STI(s) | 2.76 (1.53–4.97) | 2.86 (1.30–6.31)* | 3.32 (1.56–7.04) | |

| Blood transfusion | 0.95 (0.42–2.11) | 1.18 (0.47–2.92) | ||

| Tattoos | 0.75 (0.44–1.28) | 0.62 (0.34–1.15) | ||

| Piercings | 1.90 (0.85–4.26) | 0.59 (0.30–1.18) | ||

| Surgery | 0.98 (0.57–1.66) | 1.92 (0.95–3.88) | ||

| Mental illness | 0.75 (0.43–1.31) | 1.20 (0.65–2.21) | ||

| Prison | ||||

| Previous incarceration | 1.11 (0.65–1.91) | 1.88 (1.02–3.45) | 2.23 (1.08–4.63)* | |

| Time in prison, months, mean ± SD | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | ||

Adjusted OR = adjusted odds ratio; crude OR = crude odds ratio; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; IDU = intravenous drug user; SD = standard deviation; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Adjusted for significant interaction term between these variables (P = 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Prisons remain a concern and are a key causative factor for a myriad of problems, which ultimately turn these custodial settings into fertile breeding grounds for infectious diseases such as syphilis. Prisoners continue to show a significantly higher prevalence of T. pallidum infection, especially in developing countries.8,9,19 Thus, knowledge of syphilis in Mato Grosso do Sul, a state in Central-West Brazil that borders Paraguay and Bolivia and has the highest rate of incarceration in the country,11,20 is important for the planning of preventive measures of this disease.

The prevalence of lifetime syphilis in 12 prisons was 10.5%, with a significant difference between genders, 9.4% in men and 17% in women. This prevalence is higher than previously reported in the general population (3%). Other studies have also reported a high prevalence of lifetime syphilis in prisoners.10,18,21 However, these were conducted in only one establishment and may not represent the reality of other Brazilian prisons. Our study showed that there were differences in lifetime (15.4–2.2%) and active syphilis (35.2–0.95%) prevalence among prisons. According to our results, syphilis infection among Brazilian prisoners (10.5%) (95% CI = 9.56–11.67) is higher than that of the incarcerated population in developed countries, including France (0.5%),22 United States (0.6%),23 Italy (2.1%),24 Portugal (6.0%),25 and the developing country México (2.0%).26 However, it is lower than that of the developing country Ghana (16.5%).8

Additionally, this study showed that women were affected more often than men. This result is consistent with the higher prevalence of syphilis and other STIs in women as reported by Muga and others27 and Arredondo and others.26 However, other studies have reported that women were more likely to engage in CSW, a high-risk sexual behavior that correlates with a high prevalence of syphilis and other STIs.7,27,28 The high prevalence found in our study might be related to the high number of sexual partners reported by 53.5% of women (N = 277, P < 0.01, Table 1). However, the disparity of this infection based on sex is also likely due to the lower socioeconomic status of women prisoners, and emphasizes the need for efforts to reduce the risk of STIs, specifically in women.

Our study showed a high prevalence (3.8%) of active syphilis (2% among men; 9% among woman, P ≤ 0.01). This is consistent with a previous study in vulnerable groups that reported high rates of active syphilis among HIV positive (5.3%),18 MSM (12.3%), TW (27.0%), and MSM/TW (17.5%).6 The alarming prevalence of active syphilis in women added to high rates of unawareness of serological status warrants the attention of health-care services to improve the control and occurrence of serious forms of syphilis, such as congenital syphilis. However, 11.5% patients with active syphilis had awareness of their serological status and were not receiving treatment, likely due to the current lack of therapy available in Brazil.29 These findings show the critical necessity to implement screening programs and treatment in prison environments to help reduce T. pallidum transmission among prisoners and their contacts.

Furthermore, the high rates of active syphilis are not only established indicators of risky sexual behaviors, but are associated with sexual transmission of HIV due to the presence of genital ulceration.30 Previous study showed syphilis as a risk factor for HIV infection.31 In this scenario, intervention efforts for controlling the epidemics of syphilis should help to reduce the susceptibility to HIV infection, mainly among women, their sexual partners, and MSM.6 The cross-sectional scope of the current study did not allow us to determine whether the prisoners acquired the diseases while within or outside the prison. However, this study showed that participants had multiple sexual partners (50.3%) and also engaged in high rates of unprotected sexual intercourse (67% reported irregular condom use), thereby creating even more opportunities for T. pallidum infection transmission. Preventive interventions and education about potential risks associated with sexual practices would encourage these groups to practice safer sexual behaviors. Currently, campaigns, treatment, and prevention efforts for STIs have not been performed in Brazilian prisons. Routine screening for syphilis is an essential part of HIV care in public health programs. However, the high prevalence of lifetime syphilis, including high VDRL titers suggestive of untreated infection and risky sexual behavior, suggests the urgent need for increasing screening and detection of syphilis among Brazilian prisoners.

The multivariable analysis identified homosexual preference, positive HIV status, and history of STIs as variables associated with active syphilis among men, whereas sex with IDUs, genital ulcer disease, and previous incarceration were associated with active syphilis in women. Our study showed that genital ulcer disease increased the risk of active syphilis more than 13% in women prisoners. Fernandes and others (2014) also reported that genital ulcer diseases were associated with T. pallidum infection among MSM.6 Genital ulcer is less likely to be diagnosed in women as they are not easily seen and are usually painless.30 Sexual behaviors could be a potential risk for syphilis transmission during unprotected sex. This finding suggests that more intensive control strategies should be targeted to these places by providing education materials, condom promotion, STI screening, and treatment to reduce the risk of syphilis infection in this group. Furthermore, older age remained a protective factor in active syphilis in women. Older individuals (> 60 years old) reported stable sexual partners (5% of men and 9% women, P < 0.01). Thus, most likely this group has a smaller number of sexual partners. Although our study cannot explain why older age was a protective factor, this behavior may contribute to reducing agent transmission, warranting further research.

The high syphilis prevalence in prison systems is a public health problem. Many prisoners are incarcerated for a relatively short period and can return to the community unaware of infection and be a risk for transmission. In addition, the high rates of unprotected sex as self-reported can be serious risk behavior. Although the results of these cross-sectional studies cannot detect the causality of the transmission source (i.e., in or out of prison), they provide important data on the correlates of syphilis infection among prisoners, and may contribute to efforts to respond to the important health-care needs of these vulnerable individuals in Brazil. Despite these limitations, our study showed a high prevalence of active syphilis, especially among women prisoners. Thus, serological screening in prisons could increase the detection rate of early syphilis and reduce the infection term, as well as syphilis transmission during pregnancy.

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to the State Agency of the Administration of Prisons (AGEPEN) for their support and to the prisoner participants, without whom this study could not have been performed. We also thank the staff of the GPBMM/UFGD study group for their support, including Tháigor Rezek Varella, Isabela Jaco Carrijo, José Lourenço dos Santos Cunha e Silva, and Peceu Magyve Ragagnin de Oliveira.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ho EL, Lukehart SA, 2011. Syphilis: using modern approaches to understand an old disease. J Clin Invest 121: 4584–4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, 2012.. Global Incidence and Prevalence of Selected Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections—2008. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Reproductive Health and Research, WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization, 2014.. Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission (EMTCT) of HIV and Syphilis Global Guidance on Criteria and Processes for Validation. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministério da Saúde, 2008. Prevalências e Frequências Relativas de Doenças Sexualmente Transmissíveis (DST) em Populações Selecionadas de Seis Capitais Brasileiras, 2005 Available at: http://www.dst.uff.br/publicacoes/Prevalencias%20DST%20Brasil%20capitais_para_web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottlieb SL, Low N, Newman LM, Bolan G, Kamb M, Broutet N, 2014. Toward global prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs): the need for STI vaccines. Vaccine 32: 1527–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandes FR, et al. , 2014. Syphilis infection, sexual practices and bisexual behaviour among men who have sex with men and transgender women: a cross-sectional study. Sex Transm Infect 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parvez F, Katyal M, Alper H, Leibowitz R, Venters H, 2013. Female sex workers incarcerated in New York city jails: prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and associated risk behaviors. Sex Transm Infect 89: 280–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adjei AA, Armah HB, Gbagbo F, Ampofo WK, Boamah I, Adu-Gyamfi C, Asare I, Hesse IF, Mensah G, 2008. Correlates of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis infections among prison inmates and officers in Ghana: a national multicenter study. BMC Infect Dis 8: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazi AM, Shah SA, Jenkins CA, Shepherd BE, Vermund SH, 2010. Risk factors and prevalence of tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus among prisoners in Pakistan. Int J Infect Dis 14: 60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazel S, Baillargeon J, 2011. The health of prisoners. Lancet 377: 956–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burattini M, Massad E, Rozman M, Azevedo R, Carvalho H, 2000. Correlation between HIV and HCV in Brazilian prisoners: evidence for parenteral transmission inside prison. Rev Saude Publica 34: 431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brasil, 2014. Levantamento Nacional de Informações Penitenciárias - Dezembro de 2014. Infopen. Departamento Penitenciário Nacional. Brasília: Ministério da Justiça. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization, 2014.. Prisons and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Regional Office for Europe, WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, Riesenberg K, 2009. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. Eur J Intern Med 20: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brasil, 2014. Novo Diagnóstico de Pessoas Presas no Brasil. Departamento de monitoramento e Fiscalização do Sistema Carcerário e do Sistema de Execução de Medidas Socioeducativas (DMF/CNJ). Brasília: Conselho Nacional de Justiça.

- 16.Sgarbi RVE, et al. , 2015. A cross-sectional survey of HIV testing and prevalence in twelve Brazilian correctional facilities. PLoS One 10: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young H, Moyes A, Seagar L, McMillan A, 1998. Novel recombinant-antigen enzyme immunoassay for serological diagnosis of syphilis. J Clin Microbiol 36: 913–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callegari FM, Pinto-Neto LF, Medeiros CJ, Scopel CB, Page K, Miranda AE, 2014. Syphilis and HIV co-infection in patients who attend an AIDS outpatient clinic in Vitoria, Brazil. AIDS Behav 18 (Suppl 1): S104–S109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azbel L, Wickersham JA, Grishaev Y, Riesenberg K, 2013. Burden of infectious diseases, substance use disorders, and mental illness among Ukrainian prisoners transitioning to the community. PLoS One 8: e59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brasil, 2015. Sistema Nacional de Políticas Públicas sobre Drogas – (Sisnad), 3. ed. Available at: file:///C:/Users/cbrooks/Downloads/politicas_drogas_sisnad_3ed.pdf.

- 21.Albuquerque AC, da Silva DM, Rabelo DC, de Lucena WA, de Lima PC, Coelho MR, Tiago GG, 2014. Seroprevalence and factors associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis in inmates in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil. Cien Saude Colet 19: 2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verneuil L, Vidal JS, Ze Bekolo R, Vabret A, Petitjean J, Leclercq R, Leroy D, 2009. Prevalence and risk factors of the whole spectrum of sexually transmitted diseases in male incoming prisoners in France. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 28: 409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon L, Flynn C, Muck K, Vertefeuille J, 2004. Prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among entrants to Maryland correctional facilities. J Urban Health 81: 25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sagnelli E, et al. , 2012. Blood born viral infections, sexually transmitted diseases and latent tuberculosis in Italian prisons: a preliminary report of a large multicenter study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 16: 2142–2146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marques NM, Margalho R, Melo MJ, Cunha JG, Meliço-Silvestre AA, 2011. Seroepidemiological survey of transmissible infectious diseases in a Portuguese prison establishment. Braz J Infect Dis 15: 272–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bautista-Arredondo S, et al. , 2015. A cross-sectional study of prisoners in Mexico city comparing prevalence of transmissible infections and chronic diseases with that in the general population. PLoS One 10: e0131718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muga R, Roca J, Tor J, Pigem C, Rodriguez R, Egea JM, Vlahov D, Muñoz A, 1997. Syphilis in injecting drug users: clues for high-risk sexual behaviour in female IDUs. Int J STD AIDS 8: 225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuelter-Trevisol F, Custódio G, Silva AC, Oliveira MB, Wolfart A, Trevisol DJ, 2013. HIV, hepatitis B and C, and syphilis prevalence and coinfection among sex workers in Southern Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 46: 493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brasil, 2015. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos. Nota informativa: Abastecimento da penicilina benzatina 1.200.000 UI e espiramicina 1.500.000 UI no país. Brasília.

- 30.Arora P, Nagelkerke NJ, Jha P, 2012. A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for sexual transmission of HIV in India. PLoS One 7: e44094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng TJ, Liu XL, Cai YM, Pan P, Hong FC, Jiang WN, Zhou H, Chen XS, 2008. Prevalence of syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus infections among men who have sex with men in Shenzhen, China: 2005 to 2007. Sex Transm Dis 35: 1022–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]