Abstract.

The most common extraintestinal complication of Entamoeba histolytica is amebic liver abscess (ALA). Hepatic vein and inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombosis are rare but well-documented complications of ALA, typically attributed to mechanical compression and inflammation associated with a large abscess. We present a case of a previously healthy 43-year-old Canadian man presenting with constitutional symptoms and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. He was found to have thrombophlebitis of the IVC, accessory right hepatic vein, and bilateral iliac veins. Extensive investigations for thrombophilia were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the liver demonstrated a 3.2-cm focal area of parenchymal abnormality that was reported as presumptive hepatocellular carcinoma, and a 1.9-cm lesion in the caudate lobe with diffusion restriction and peripheral rim enhancement. Despite multiple biopsy attempts, a histopathological diagnosis was not achieved. Abdominal pain and fever 4 months later prompted repeat ultrasound demonstrating a 10.4- × 12.0-cm rim-enhancing fluid attenuation lesion felt to represent a liver abscess. Thick dark “chocolate brown” drainage from the lesion and positive serology for E. histolytica confirmed the diagnosis of ALA acquired from a previous trip to Cuba. The patient was started on treatment with metronidazole and paromomycin and repeat abdominal ultrasound demonstrated resolution of the abscess. This case is the first to demonstrate extensive IVC thrombosis secondary to a relatively small occult ALA and emphasizes the thrombogenic potential of ALA. Amebic infection should be considered as a rare cause of IVC thrombosis in the correct clinical context.

INTRODUCTION

The protozoan Entamoeba histolytica is the most frequent cause of symptomatic intestinal amoebiasis.1 Although E. histolytica is found worldwide, there is a disproportionate burden in developing countries. The most common extraintestinal complication of E. histolytica is an amebic liver abscess (ALA). An ALA arises from the hematogenous spread of amebic trophozites that cross the colonic mucosa and enter the liver through the portal circulation. Patients can present within months to years after travel to an endemic country.2 Thrombosis is a rare complication of ALA mainly documented in case reports.3–9 The mechanism of thrombosis has been primarily explained by mechanical compression of the vascular structures and localized inflammation.3,10

CASE

We present a case of a 43-year-old Canadian man with a 1-month history of intermittent fever, anorexia, headache, and fatigue. A few days prior to his presentation he began to experience right upper quadrant abdominal tenderness. His past medical history was significant for gout, and a recent diagnosis of dyspepsia for which he was started on pantoprazole. He had traveled to Cuba 5 months earlier with no associated diarrheal illness.

The workup was initiated as an outpatient. He was found to have mildly elevated liver enzymes with alanine transaminase 79 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 152 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 192 U/L, white blood cell count 9.9 × 109/L, hemoglobin 120 mg/L, and platelets 437 × 109/L. Two liver ultrasounds demonstrated fatty infiltration only. At this time, his presentation was felt to be most in keeping with a viral infection. Serological investigations were negative for hepatitis A, B, and C, cytomegalovirus, and acute Epstein–Barr virus.

One month later, he presented to hospital with ongoing fever, sweats, weight loss, and right-sided flank pain. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan on June 4, 2015, demonstrated bilateral perinephric, pericaval and periaortic fat stranding, thickening of Gerota’s fascia, and a small amount of fluid in the pelvis; imaging features that were suspicious for bilateral pyelonephritis. However, urinalysis was bland and cultures were negative making pyelonephritis unlikely. The differential diagnosis entertained was a medium-vessel vasculitis with aortitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, occult infection, or malignancy. Inflammatory markers were elevated with erythrocyte sedimentation rate 110 mm/hour and C-reactive protein 206 mg/L. There was no evidence of connective tissue disease or vasculitis based on compliment levels, antinuclear antibody, antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody, rheumatoid factor, and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibody testing. To assess for aortitis, a CT angiogram of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was completed on June 8, 2015, revealing a possible lesion in the caudate lobe with thrombophlebitis of the inferior vena cava (IVC), increasing inflammatory changes, notable bladder wall thickening, and an irregular 1.6-cm density in the left lower lung. D-dimer was elevated at 3670 μg/L. The patient was started empirically on an intravenous heparin infusion. CT venogram confirmed the presence of an occlusive IVC thrombus involving the intrahepatic IVC, inferior right hepatic vein, and iliac veins (Figure 1). The patient was transitioned to dalteparin.

Figure 1.

Initial abdominal computed tomography venogram in June 2015 showing inferior vena cava and iliac vein thrombosis and a small 1.9-cm mass within the caudate lobe (arrow).

Given the unexplained extensive IVC and hepatic vein thrombosis, testing was conducted for the JAK2 V617F mutation, antiphospholipid antibodies, antithrombin deficiency, activated protein C resistance (factor V Leiden mutation), prothrombin gene mutation G20210A, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, all of which were negative. Malignancy workup was negative, including upper and lower endoscopy, positron emission tomography–CT of the lung lesion, bladder cystoscopy, and alfa-fetoprotein. Given the extensive symptomatic thrombosis, catheter-directed thrombolysis was performed with repeat venogram showing resolution of thrombus.

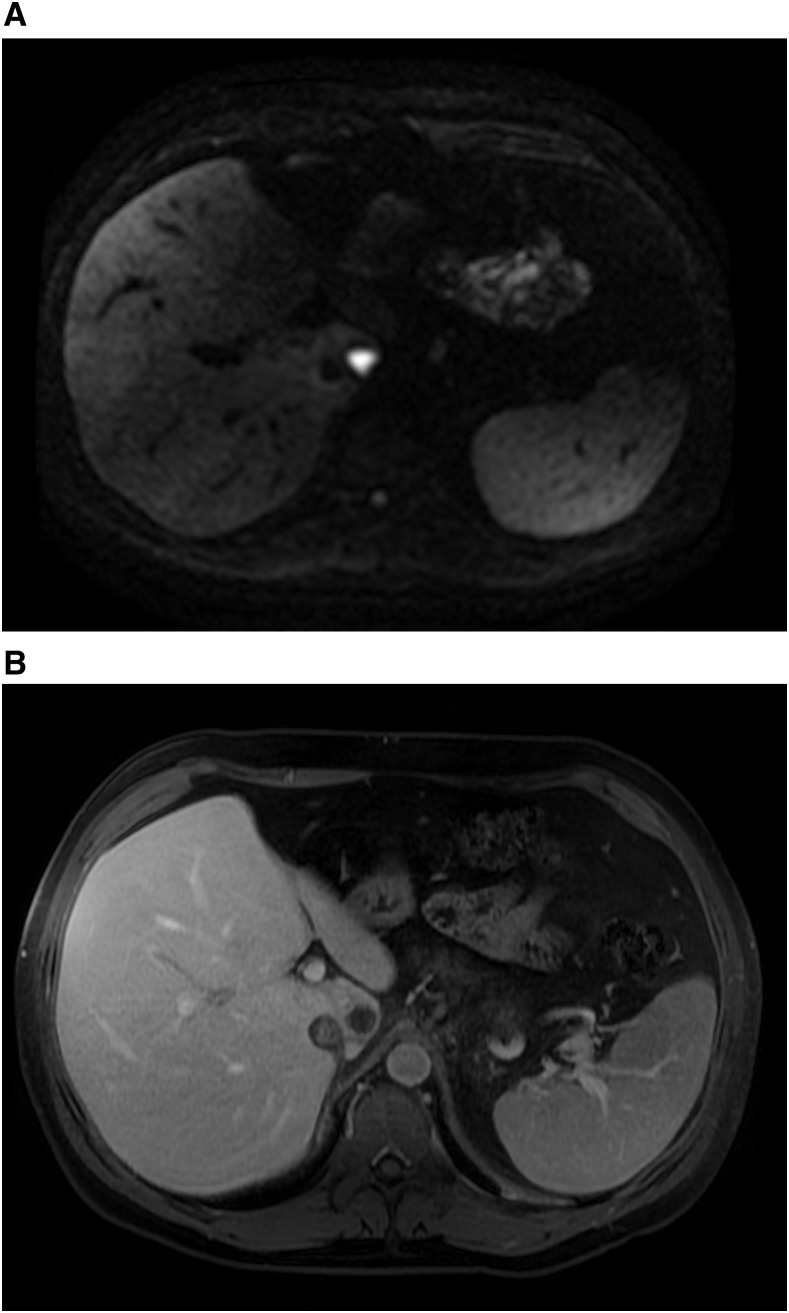

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) liver was completed shortly thereafter on June 19, 2015, to assess the possible caudate lobe lesion on CT scan. There was a well-circumscribed round 1.9-cm T2 hyperintense and T1 hypointense lesion found within the caudate lobe in close vicinity of the IVC thrombus that showed significant diffusion restriction (Figure 2A) and postcontrast rim enhancement (Figure 2B). In addition, there was an ill-defined area of altered signal along the periphery of segment V, which was suspicious for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with associated tumor thrombus. Liver biopsy of the lesion was nondiagnostic for malignancy. During brief interruption of anticoagulation for this procedure, the patient developed a new symptomatic right leg deep vein thrombosis. Repeat biopsies were attempted on three further occasions over the subsequent month, all with nondiagnostic pathology. He was maintained on therapeutic dalteparin and decision was made for discharge home with ongoing outpatient workup.

Figure 2.

Diffusion weighted (A) and postcontrast axial 3d T1 fat saturated (B) magnetic resonance images demonstrate a small lesion in the caudate lobe that shows significant diffusion restriction, peripheral enhancement, and lack of central enhancement, in retrospect favoring abscess rather than tumor.

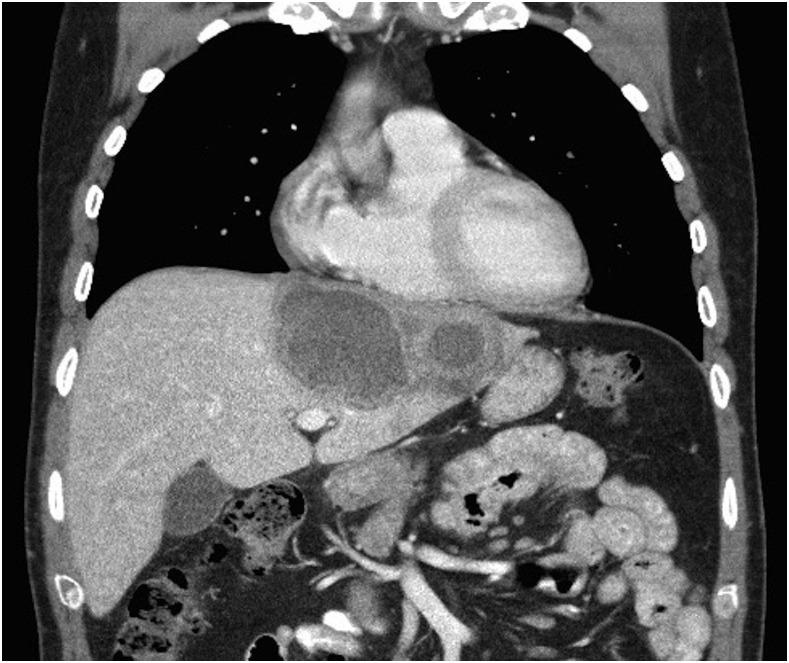

Given the underlying suspicion for HCC, a follow-up contrast-enhanced CT was completed 3 months later. This demonstrated a large irregular 10.4- × 12-cm lesion spanning segments 2, 3, 4a, and 4b of the liver and a persistent lesion in the caudate lobe measuring 1.7 × 1.9 cm (Figure 3). Given the thick enhancing walls and internal nonenhancing areas of central low attenuation, these lesions were felt to have characteristic appearances of hepatic abscesses, perhaps secondary to amoebiasis.

Figure 3.

Repeat contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography scan 3 months after discharge showing rim-enhancing lesions with central low attenuation (arrows), the larger measuring 10.4 × 12 cm with ongoing involvement of the caudate lobe (1.7 × 1.9 cm).

A pigtail catheter was inserted draining thick chocolate-brown fluid, suspicious for E. histolytica. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay from the aspirated fluid was negative; however, this test is validated for intestinal E. histolytica. Serology was strongly positive for E. histolytica with an IgG titer of 1:3,200, confirming the diagnosis of amebic infection given the high sensitivity and specificity of serologic testing (> 94% and > 95%, respectively).2 The patient was treated with metronidazole 500 mg per os three times a day for 10 days followed by paromomycin 30 mg/kg for 7 days. Repeat ultrasound illustrated resolution of the collection. Given that no malignancy was demonstrated on repeat images, the patient was changed from dalteparin to apixaban for ongoing anticoagulation. A follow-up CT in April 2016 showed complete resolution of the hepatic abscesses with minor residual scarring within the liver. There was persistent thrombosis of the intrahepatic IVC with formation of collateral draining channels.

DISCUSSION

IVC and hepatic thrombosis is a rare complication of ALA mainly described in case reports.3–9 Our case is unique in that it is the first to demonstrate the presence of extensive IVC and hepatic thrombosis secondary to an ALA that was initially occult on imaging. Ray and others reported a case in India where a 15- × 10-cm collection was found on ultrasound abutting the IVC with associated thrombus.3 McKenzie and others reported the first pulmonary embolism in the setting of ALA within the United States, associated with a large 8.5 × 9.6 × 6.8 cm abscess.4 Other case reports document similarly large amebic abscesses in the setting of thrombus.5–9 The association of thrombus and large ALA is in accordance with the proposed mechanism of thrombus development: mechanical compression and active inflammation. Our case suggests that mechanical compression is not necessary for the development of thrombus, and emphasizes the thrombogenic potential of amoebiasis. Further, the recurrence of thrombus after a brief period of bridging anticoagulation suggests a more profound thrombogenic potential of ALA than was previously understood.

In this case, the lesion was initially so small that it was not demonstrated on serial ultrasounds. This led to a substantial delay in the diagnosis and management of this patient. However, a further delay is likely attributable to an anchoring bias. The patient lacked substantial risk factors for HCC and tumor markers were negative, yet due to the imaging findings, HCC was deemed the most likely cause. It was not until a large collection was found and subsequently drained that the diagnosis of E. histolytica was considered. Retrospective review of the initial MRI was illuminating: the findings were suggestive of a small caudate lobe liver abscess rather than a neoplastic process given the presence of avid diffusion restriction with significantly higher apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values and lack of internal enhancement (Figure 2). Park and others showed that the mean ADC values of abscesses were significantly higher than those in malignancies.11 Moreover, a solid hepatic neoplasm would characteristically demonstrate enhancement within the area of diffusion restriction, whereas a nonhemorrhagic necrotic neoplastic lesion would not demonstrate diffusion restriction. Finally, the area of altered signal in segment V, reported as suspicious for HCC on the initial MRI, was associated with duct ectasia suggestive of focal hepatitis. This finding is more in keeping with inflammation than malignancy. The initial lack of recognition of these distinguishing features may be explained by the relative infrequency of ALA in the North American setting. Further, all previously published cases of ALA-associated IVC thrombus occurred in patients born within endemic countries. This is the first case describing an IVC thrombus as a complication of ALA in a patient born in North America with short-term travel to an endemic country. Given the frequency of international travel, as well as growing immigrant and refugee populations in North America, ameba infection should be entertained in the differential diagnosis of unprovoked IVC thrombus.

CONCLUSION

Clinicians working in nonendemic areas need to be aware that ALA is a rare but known cause of thrombosis. This case is the first to identify extensive thrombosis prior to the classic radiographic finding of ALA, suggesting a more profound thrombogenic potential of ALA than previously thought. MRI features can help distinguish ALA from other liver lesions, prompting earlier diagnosis and appropriate therapy for this condition.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA, Jr, 2003. Amebiasis. N Engl J Med 348: 1565–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanley SL, Jr, 2003. Amoebiasis. Lancet (London, England) 361: 1025–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray S, Khanra D, Saha M, Talukdar A, 2012. Amebic liver abscess complicated by inferior vena cava thrombosis: a case report. Med J Malaysia 67: 524–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKenzie D, Gale M, Patel S, Kaluta G, 2015. Pulmonary thromboembolism complicating amebic liver abscess: first reported case in the united states-case report and literature review. Case Rep Infect Dis 2015: 516974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sodhi KS, Ojili V, Sakhuja V, Khandelwal N, 2008. Hepatic and inferior vena caval thrombosis: vascular complication of amebic liver abscess. J Emerg Med 34: 155–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarda AK, Mittal R, Basra BK, Mishra A, Talwar N, 2011. Three cases of amoebic liver abscess causing inferior vena cava obstruction, with a review of the literature. Korean J Hepatol 17: 71–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddiqui M, Gupta A, Kazmi A, Chandra D, Grover V, Gupta V, 2013. Inferior vena caval and right atrial thrombus complicating amoebic liver abscess. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 17: 872–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan S, Ameen Rauf M, 2009. Amoebic liver abscesses complicated by inferior vena cava and right atrium thrombus. Trop Doct 39: 177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta A, Dhua AK, Siddiqui MA, Dympep B, Grover V, Gupta VK, Sen A, 2013. Inferior vena cava thrombosis in a pediatric patient of amebic liver abscess. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 18: 33–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okuda K, 2002. Obliterative hepatocavopathy-inferior vena cava thrombosis at its hepatic portion. Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Dis Int 1: 499–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park HJ, Kim SH, Jang KM, Lee SJ, Park MJ, Choi D, 2013. Differentiating hepatic abscess from malignant mimickers: value of diffusion-weighted imaging with an emphasis on the periphery of the lesion. J Magn Reson Imaging 38: 1333–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]