ABSTRACT

Background: predicting the development of severe disease has remained a major challenge in management of acute pancreatitis. The Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) is easy to calculate from the data available in the first 24 hours. Here, we performed a systematic review to determine the prognostic accuracy of the BISAP for severe acute pancreatitis (SAP).

Methods: major databases of biomedical publications were searched during the first week of October 2015. Two independent reviewers searched records in two phases. Studies that reported prognostic accuracy of the BISAP for SAP from prospective cohorts were included. The pooled area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) was calculated.

Results: Twelve studies were included for data-synthesis and methodology quality assessment was performed for 10. All the studies had enrolled consecutive patients, had a broad spectrum of the disease severity, reported explicit interpretation of the predictor, outcome of interest was well defined and had adequate follow-up. Blinded outcome assessment was reported in only one study. The pooled AUC was 0.85 (95% CI 0.80–0.90). There was significant heterogeneity, I 2 86.6%. Studies using revised Atlanta classification in defining SAP had a pooled AUC of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.90–0.95), but heterogeneity persisted, I 2 67%. Subgroup analysis based on rate of SAP (>20% vs <20%) did not eliminate the heterogeneity.

Conclusion: the BISAP has very good predictive performance for SAP across different patient population and etiologies. Studies to evaluate the impact of incorporating the BISAP into clinical practice to improve outcome in acute pancreatitis are needed before adoption could be advocated with confidence.

KEYWORDS: acute pancreatitis, systematic review, clinical prediction score

1. Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is the most common gastrointestinal cause of hospitalization [1]. The rate of hospitalization continues to grow [2]. Analysis of national inpatient sample databases showed a 33% increase in acute pancreatitis-related hospitalization over a 7-year period from 1997 to 2003 [3]. The rise in incidence of acute pancreatitis is probably a result of a combination of increasing incidence of risk factors such as obesity (gallstone disease) and more testing [4].

The severity of acute pancreatitis is the major determinant of clinical outcomes with mortality ranging from 1–3% in mild to over 20% in severe acute pancreatitis (SAP), defined by the presence and persistence of organ failure [5,6]. A major challenge for care providers is to predict the development of severe pancreatitis early in the course, which would improve patient management and resource utilization. But most of the patients who develop severe pancreatitis during hospitalization present to the emergency room without organ failure initially, and no single laboratory test has been shown to reliably predict subsequent progression to severe pancreatitis. Therefore, an accurate clinical prediction rule has the potential to dramatically improve the management of acute pancreatitis.

The Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) was developed in 2008 [7]. It is an easy to calculate from data points available in the first 24 hours of presentation to emergency department (Box 1). Other clinical prediction scores reported in the literature are cumbersome to calculate, need clinical and laboratory data from 48 hours of hospitalization and do not outperform BISAP in predicting severe pancreatitis [8,9]. This is all the more relevant since the first 24–48 hour period is the most crucial time window in management of pancreatitis, and by the end of 48 hours most patients have revealed the severity of their illness with clinical improvement or development of organ failure.

Multiple studies have validated the performance of the BISAP in predicting acute severe pancreatitis. A systematic review for accurate estimation of the predictive performance of the BISAP can provide an objective and quantitative estimate to complement clinical assessment in acute pancreatitis. Multiple prospective studies have been published since a systematic review was published [10]. We thus have aimed to perform a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the predictive performance of the BISAP for SAP.

1.1. Methods

The reporting guidelines of Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) were followed in this systematic review and meta-analysis [11].

1.1.1. Search

The search was performed in the first week of October 2015 by one of the investigators (S.C.) who has prior experience in performing searches for systematic reviews. Major databases of biomedical publications (Medline, Scopus and Web of Science) were included. The period of search was limited to 2008–2015, as the BISAP was developed in 2008. Language restrictions were not applied. Details of the search strategy are described in Appendix 1. Reference lists of the eligible studies were searched to identify additional studies.

1.1.2. Study selection

We included studies that reported the predictive performance of the BISAP for SAP from prospective cohorts of patients hospitalized for acute pancreatitis. Retrospectives studies and studies not based on original data or published in abstract format only were excluded. Studies published in a non-English language were included in data-synthesis for quantitative analysis but excluded from the methodology quality assessment.

Studies were searched in two phases, by two independent reviewers (A.M., R.B.). In phase I, study titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility. Full reports of studies deemed eligible by either reviewer in phase I were obtained. In phase II, both reviewers assessed the full text of each study for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by consensus in the presence of the third reviewer (S.C.).

1.1.3. Methodology quality assessment

The quality assessment parameters for study methodology were adopted from McGinn et al.’s users’ guide [12]. These parameters assess patient selection for clinical and demographic characteristics, severity of the disease, accurate interpretation of the predictors and the outcomes (mutually blinded) and adequate follow-up (defined as available in >95% of enrolled subjects). Two reviewers performed quality assessment, independently (S.C., A.M.). Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

1.1.4. Data extraction

Two reviewers (S.C., A.M.) extracted data from all the included studies. A standardized electronic data-extraction datasheet was used. Because most of the studies did not report number of patients and outcomes for each BISAP score, the area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) was collected. The clinical outcome of interest was SAP. Acute severe pancreatitis is defined based on the presence of organ failure (Atlanta classification) or persistence of organ failure for more than 48 hours (revised Atlanta classification) [13,14].

1.1.5. Data synthesis and analysis

Pooled area under the AUC was calculated to determine BISAP’s predictive performance. MedCalc statistical software (Version 17.4.4) was used to calculate the pooled AUC using a random effects model. Heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and I 2 statistics. A p value <0.1 was considered significant for heterogeneity. An a priori subgroup analysis was performed for severe pancreatitis rate (<20% and 20% or higher) and definition of SAP, based on the Atlanta classification versus the revised Atlanta classification. Funnel plot analysis was used to address heterogeneity.

2. Results

2.1. Study selection

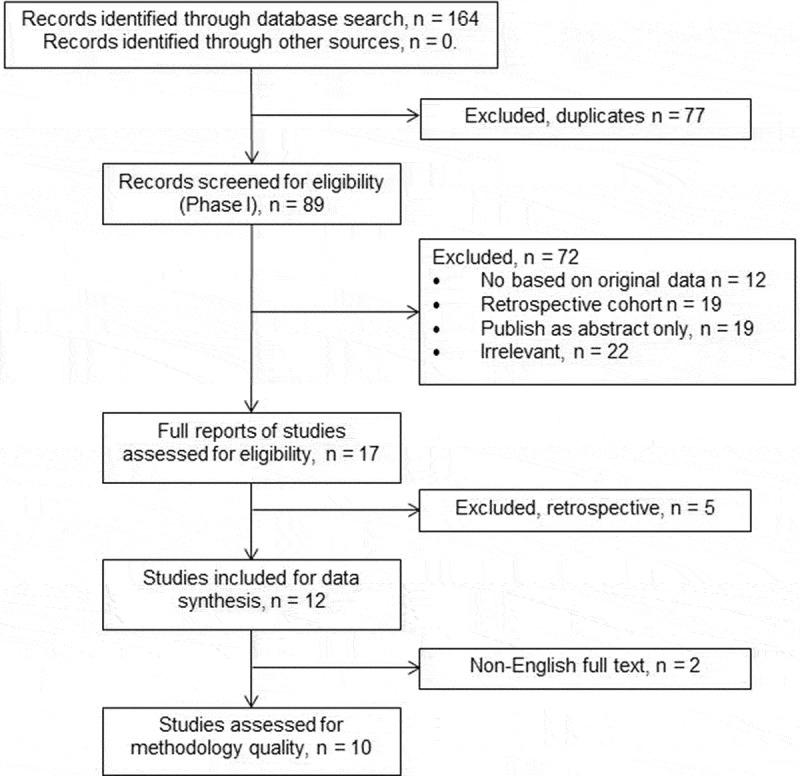

The study selection process is summarized in Figure 1. A total of 12 validation studies were included in data synthesis and quality assessment of the study methodology was performed for 10 studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

2.2. Characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of individual studies are summarized in Table 1. Twelve studies encompassing a total of 3069 patients were included in data synthesis for the meta-analysis. Three cohorts were from India, two from the USA, two from Peru and one each from South Korea, China, Pakistan, Poland and Serbia. All the patients were hospitalized with a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Sixty percent of the patients were male. Average age ranged from 39 years to 61 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies and performance of the Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) score.

| Study | Country | N | Male (%) | Mean age (yrs) | Alcoholic (%) | Gallstone (%) | SAP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yadav 2015 | India | 119 | 71 | 39 | 40 | 31 | 35.3 |

| Mok 2015 | USA | 266 | 59 | 49 | 37 | 26 | 15.4 |

| Campos 2015 | Peru | 334 | 30 | 42 | 1 | 87 | 8.4 |

| Bezmareviu 2012 | Serbia | 51 | 67 | 61 | 22 | 28 | 56.9 |

| Bollen 2012 | USA | 150 | 56 | 54 | 23 | 48 | 19.3 |

| Khanna 2013 | India | 72 | 51 | 41 | 18 | 44 | 43.1 |

| Kim 2013 | Korea | 50 | 68 | 60 | 46 | 24 | 48.0 |

| Senapati 2014 | India | 246 | 62 | 42 | 53 | 28 | 15.9 |

| Surco 2012 | Peru | 329 | 65 | NA | NA | 74 | 27.1 |

| Yu 2014 | China | 358 | 77 | 47 | NA | NA | 15.4 |

| Shabbir 2015 | Pakistan | 80 | 44 | 47 | NA | NA | 31.3 |

| Koziel 2015 | Poland | 1014 | 63 | 54 | 27 | 34 | 6.9 |

| Pooled | 3069 | 60 | 16 |

NA, not available; SAP, severe acute pancreatitis.

2.3. Methodology quality assessment

Scoring of individual studies on methodology quality assessment parameters is presented in Table 2. All the studies had enrolled a consecutive cohort of patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and included a broad spectrum of the disease severity. Follow-up was adequate in all the reviewed studies. Explicit and accurate interpretation of the predictor was reported in each study. The outcome of interest (SAP) was well defined in each study. Six studies used the Atlanta classification [15–20] and the other six used the revised Atlanta classification [21–26]. Blinded outcome assessment was reported in only one study [17].

Table 2.

Methodology quality assessment of included studies.

| Parameters | Yadav 2015 | Bezmareviu 2012 | Senapati 2014 | Kim 2013 | Khanna 2013 | Bollen 2012 | Moke 2015 | Shabbir 2015 | Koziel 2015 | Campos 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

|

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Y | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

|

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

NP, not reported; U, unclear; Y, yes.

2.4. Predictive performance of BISAP

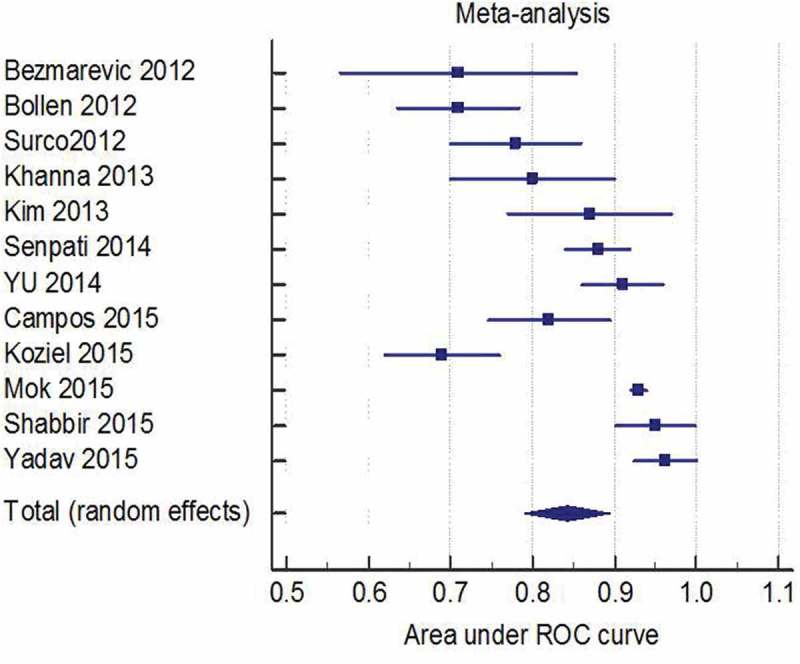

Of the 3069 patients from the included studies, 16% of patients developed SAP. The pooled AUC was 0.84 (95% CI, 0.79–0.90); see Figure 2. There was significant heterogeneity in pooled estimates, I 2 91%, p < 0.001. A funnel plot showed significant asymmetry (Figure 3). The distribution of asymmetry is consistent with publication bias [27].

Figure 2.

Pooled area under the receiver operating curve to demonstrated prognostic performance of the Bedside Index for Severe Acute Pancreatitis, 0.84 (95%, 0.79–0.90.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot showing assymetry which represents probable publication bias.

2.5. Heterogeneity

A priori subgroup analyses were performed to address the heterogeneity. Studies were grouped based on the prevalence of SAP (<20% and 20% or higher) and definition used for SAP, 1992 Atlanta classification versus the revised Atlanta classification. In studies with an SAP rate of >20%, the pooled AUC was 0.86 (95% CI, 0.79–0.93) with I 2 84% and 0.83 (95% CI, 0.75–0.90) with I 2 94% in studies with <20%. The pooled AUC from studies using the revised Atlanta classification was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.80–0.94), I 2 92%, p < 0.001. Studies using the original Atlanta classification had a pooled AUC of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.74–0.88), I 2 86% p < 0.001. Since heterogeneity still persisted, a funnel plot was constructed for studies using the revised Atlanta classification and outlier studies were excluded. Both of the excluded studies had a remarkably low rate of SAP, 6.9% and 8.4% [24,25]. The pooled AUC from the remaining four studies using the revised Atlanta classification was 0.92 (95% CI, 90–95), but heterogeneity persisted, I 2 67% p = 0.029,

3. Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, a pooled analysis from 12 prospective cohorts demonstrated very good performance of BISAP for predicting SAP across different patient populations and severity of disease. The performance of BISAP was higher if severe pancreatitis was defined as persistence of organ failure for 48 hours or longer.

3.1. External validity

Twelve prospective cohorts were identified to calculate the pooled estimate. It included 3069 patients hospitalized with acute pancreatitis, of whom 491 developed SAP. Patient selection was consecutive and represented a wide range of severity of pancreatitis and varied etiologies (with gallstone and alcohol predominating). Therefore, inclusion of a good mix of etiology, pancreatitis severity and patient demographics with a large number of patients ensures excellent external validity of pooled estimates from this study.

3.2. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include a search strategy that included three major databases of biomedical publications without any language restrictions and searching the bibliographies of the included studies. We used a robust method in conducting systematic reviews and two reviewers performed the study selection, data extraction and the methodology quality assessment of the included studies. Including prospective cohorts ensured accurate assessment of predictors because for most patients the eventual diagnostic outcome was not available at the time of predictor assessment.

This study was limited by relatively small numbers of studies being available in the literature, limited reporting of data and heterogeneity between the studies. This limits the quality of the evidence and ability to perform analysis at different cut-off points to determine sensitivity and specificity. There is probable publication bias. Efforts were made to minimize the publication bias, which included not using language restriction in the search, a manual search of reference lists of included studies and the use of multiple databases. Also, a random effect model was used in calculating pooled estimates instead of a fixed effect model. A random effect model provides more conservative pooled estimates.

3.3. Clinical implications and future direction

The BISAP is an easy-to-calculate clinical prediction scale using data from the initial clinical assessment of patients and routine laboratory data. Pooled estimates in the current study demonstrate its very good performance in predicting severe acute pancreatitis. The ease of calculation and accuracy make the BISAP a valuable tool for clinical providers caring for patients with acute pancreatitis. An implementation study is important before widespread adoption of a clinical prediction score can be recommended [28]. To date, no studies have reported the impact of incorporating the BISAP into clinical practice to improve outcome in the management of acute pancreatitis, and further research in this area is warranted.

| Box 1. Variables included in Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) score. |

|

| To calculate the BISAP, sum the number of positive variables (0–5). |

Funding Statement

None.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1]. Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the USA: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(1179–87):e1–e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Peery AF, Crockett SD, Barritt AS, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the USA. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(1731–1741):e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Brown A, Young B, Morton J, et al. Are health related outcomes in acute pancreatitis improving? an analysis of national trends in the U.S. from 1997 to 2003. JOP. 2008;9:408–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Yadav D, Ng B, Saul M, et al. Relationship of serum pancreatic enzyme testing trends with the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2011;40:383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Buter A, Imrie CW, Carter CR, et al. Dynamic nature of early organ dysfunction determines outcome in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2002;89:298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Mofidi R, Duff MD, Wigmore SJ, et al. Association between early systemic inflammatory response, severity of multiorgan dysfunction and death in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2006;93:738–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Wu BU, Johannes RS, Sun X, et al. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: a large population-based study. Gut. 2008;57:1698–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Zhang J, Shahbaz M, Fang R, et al. Comparison of the BISAP scores for predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis in Chinese patients according to the latest Atlanta classification. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:689–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Park JY, Jeon TJ, Ha TH, et al. Bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis: comparison with other scoring systems in predicting severity and organ failure. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12:645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Gao W, Yang HX, Ma CE.. The value of BISAP score for predicting mortality and severity in acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. McGinn TG, Guyatt GH, Wyer PC, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXII: how to use articles about clinical decision rules. Evidence-based medicine working group. JAMA. 2000;284:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Bradley EL., 3rd. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis–2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Kim BG, Noh MH, Ryu CH, et al. A comparison of the BISAP score and serum procalcitonin for predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis. Korean J Intern Med. 2013;28:322–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Bezmarević M, Kostić Z, Jovanović M, et al. Procalcitonin and BISAP score versus C-reactive protein and APACHE II score in early assessment of severity and outcome of acute pancreatitis. Vojnosanitetski Pregled. 2012;69:425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Bollen TL, Singh VK, Maurer R, et al. A comparative evaluation of radiologic and clinical scoring systems in the early prediction of severity in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Khanna AK, Meher S, Prakash S, et al. Comparison of Ranson, Glasgow, MOSS, SIRS, BISAP, APACHE-II, CTSI scores, IL-6, CRP, and procalcitonin in predicting severity, organ failure, pancreatic necrosis, and mortality in acute pancreatitis. HPB Surg. 2013;2013:367581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Surco Y, Huerta Mercado J, Pinto J, et al. Early prediction of severity in acute pancreatitis. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2012;32:241–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Shabbir S, Jamal S, Khaliq T, et al. Comparison of BISAP score with Ranson’s score in determining the severity of acute pancreatitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25:328–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Senapati D, Debata PK, Jenasamant SS, et al. A prospective study of the Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) score in acute pancreatitis: an Indian perspective. Pancreatology. 2014;14:335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Yu XE, Deng YH, Huang PN, et al. EPIC combined with NLR vs BISAP for early prediction of severity of acute pancreatitis. World Chin J Digestology. 2014;22:4345–4351. [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Mok SR, Mohan S, Elfant AB, et al. The acute physiology and chronic health evaluation IV, a new scoring system for predicting mortality and complications of severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2015;44:1314–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Pérez Campos A, Bravo Paredes E, Prochazka Zarate R, et al. [BISAP-O y APACHE-O: utility in predicting severity in acute pancreatitis in modified Atlanta classification]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2015;35:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Koziel D, Gluszek S, Matykiewicz J, et al. Comparative analysis of selected scales to assess prognosis in acute pancreatitis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29:299–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Yadav J, Yadav SK, Kumar S, et al. Predicting morbidity and mortality in acute pancreatitis in an Indian population: a comparative study of the BISAP score, Ranson’s score and CT severity index. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2016;4:216–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1119–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Stiell IG, Wells GA. Methodologic standards for the development of clinical decision rules in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]