Abstract

Importance

The causal direction and magnitude of the association between telomere length and incidence of cancer and non-neoplastic diseases is uncertain owing to the susceptibility of observational studies to confounding and reverse causation.

Objective

To conduct a Mendelian randomization study, using germline genetic variants as instrumental variables, to appraise the causal relevance of telomere length for risk of cancer and non-neoplastic diseases.

Data Sources

Genomewide association studies (GWAS) published up to January 15, 2015.

Study Selection

GWAS of noncommunicable diseases that assayed germline genetic variation and did not select cohort or control participants on the basis of preexisting diseases. Of 163 GWAS of noncommunicable diseases identified, summary data from 103 were available.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Summary association statistics for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are strongly associated with telomere length in the general population.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for disease per standard deviation (SD) higher telomere length due to germline genetic variation.

Results

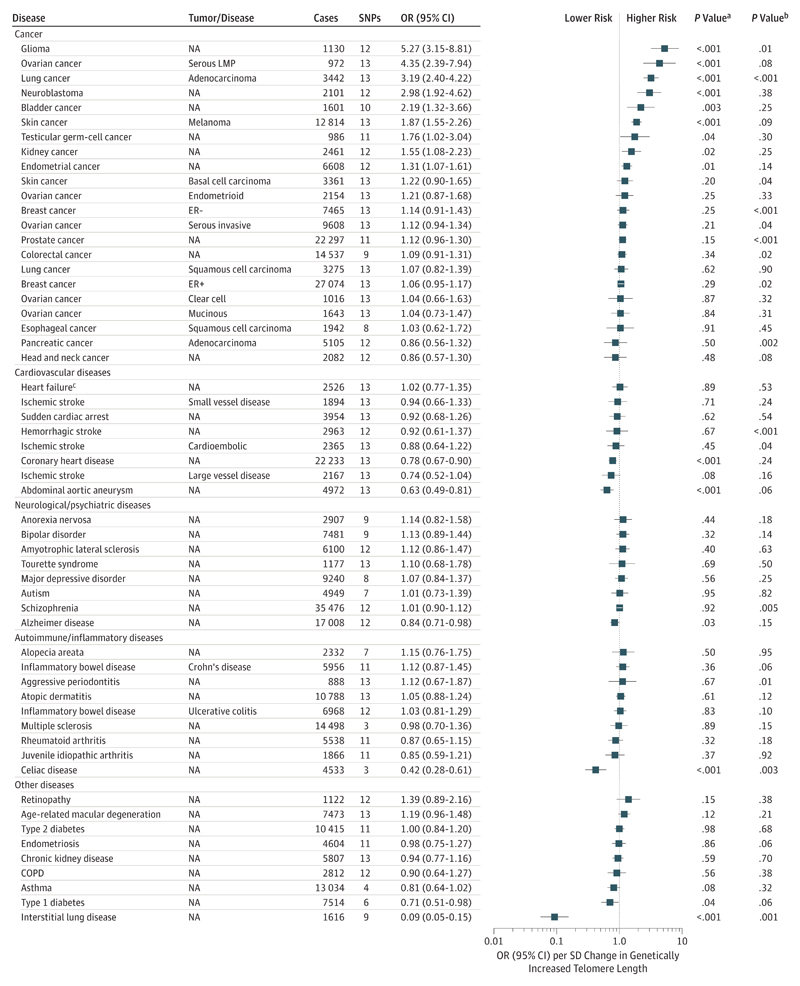

Summary data were available for 35 cancers and 48 non-neoplastic diseases, corresponding to 420 081 cases (median cases, 2526 per disease) and 1 093 105 controls (median, 6789 per disease). Increased telomere length due to germline genetic variation was generally associated with increased risk for site-specific cancers. The strongest associations (ORs [95% CIs] per 1-SD change in genetically increased telomere length) were observed for glioma, 5.27 (3.15-8.81); serous low-malignant-potential ovarian cancer, 4.35 (2.39-7.94); lung adenocarcinoma, 3.19 (2.40-4.22); neuroblastoma, 2.98 (1.92-4.62); bladder cancer, 2.19 (1.32-3.66); melanoma, 1.87 (1.55-2.26); testicular cancer, 1.76 (1.02-3.04); kidney cancer, 1.55 (1.08-2.23); and endometrial cancer, 1.31 (1.07-1.61). Associations were stronger for rarer cancers and at tissue sites with lower rates of stem cell division. There was generally little evidence of association between genetically increased telomere length and risk of psychiatric, autoimmune, inflammatory, diabetic, and other non-neoplastic diseases, except for coronary heart disease (OR, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.67-0.90]), abdominal aortic aneurysm (OR, 0.63 [95% CI, 0.49-0.81]), celiac disease (OR, 0.42 [95% CI, 0.28-0.61]) and interstitial lung disease (OR, 0.09 [95% CI, 0.05-0.15]).

Conclusions and Relevance

It is likely that longer telomeres increase risk for several cancers but reduce risk for some non-neoplastic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases.

At the ends of chromosomes, telomeres are DNA-protein structures that protect the genome from damage, shorten progressively over time in most somatic tissues,1 and are proposed physiological markers of aging.2,3 Shorter leukocyte telomeres are correlated with older age, male sex, and other known risk factors for noncommunicable diseases4–6 and are generally associated with higher risk for cardiovascular diseases,7,8 type 2 diabetes,9 and nonvascular, nonneoplastic causes of mortality.8 Whether these associations are causal, however, is unknown. Telomere length has also been implicated in risk of cancer, but the direction and magnitude of the association is uncertain and contradictory across observational studies.10–14 The uncertainty reflects the considerable difficulty of designing observational studies of telomere length and cancer incidence that are sufficiently robust to reverse causation, confounding, and measurement error.

The aim of the present report was to conduct a Mendelian randomization study, using germline genetic variants as instrumental variables for telomere length, to help clarify the nature of the association between telomere length and risk of cancer and non-neoplastic diseases. The approach, which mimics the random allocation of individuals to the placebo and intervention arms of a randomized clinical trial, allowed us to: (1) estimate the direction and broad magnitude of the association of telomere length with risk of multiple cancer and non-neoplastic diseases; (2) appraise the evidence for causality in the estimated etiological associations; (3) investigate potential sources of heterogeneity in findings for site-specific cancers; and (4) compare genetic estimates with findings based on directly measured telomere length in prospective observational studies.

Methods

Study Design

The design of our study, illustrated in eFigure 1 in Supplement 1, had 3 key components: (1) the identification of genetic variants to serve as instruments for telomere length; (2) the acquisition of summary data for the genetic instruments from genomewide association studies (GWASs) of diseases and risk factors for noncommunicable diseases; and (3) the classification of diseases and risk factors into primary or secondary outcomes based on a priori statistical power. As a first step, we searched the GWAS catalog15,16 on January 15, 2015, to identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with telomere length. To supplement the list with additional potential instruments, we also searched the original study reports curated by the GWAS catalog (using a P value threshold of 5 × 10−8).17–25 We acquired summary data for all SNPs identified by our search from a meta-analysis of GWASs of telomere length, involving 9190 participants of European ancestry.18

The second key component of our design strategy involved the acquisition of summary data, corresponding to the selected genetic instruments for telomere length, from GWASs of noncommunicable diseases and risk factors (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). As part of this step, we invited principal investigators of noncommunicable disease studies curated by the GWAS catalog15,26 to share summary data for our study. We also downloaded summary data for diseases and risk factors from publically available sources, including study-specific websites, dbGAP, ImmunoBase, and the GWAS catalog (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1).

The third key component of our design strategy was the classification of diseases and risk factors into either primary or secondary outcomes, which we defined on the basis of a priori statistical power to detect associations with telomere length. Primary outcomes were defined as diseases with sufficient numbers of cases and controls for greater than 50% statistical power, and secondary outcomes were defined as diseases with 50% or less statistical power to detect odds ratios (ORs) of 2.0 or higher per standard deviation (SD) change in genetically increased telomere length (α assumed to be .01). All risk factors were defined as secondary outcomes. Risk factors with less than 50% statistical power were excluded.

Further details on our design strategy can be found in Supplement 1.

Comparison With Prospective Observational Studies

We searched PubMed for prospective observational studies of the association between telomere length and disease (see eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 1 for details of the search strategy and inclusion criteria). Study-specific relative risks for disease per unit change or quantile comparison of telomere length were transformed to an SD scale using previously described methods.27 Hazard ratios, risk ratios, and ORs were assumed to approximate the same measure of relative risk. Where multiple independent studies of the same disease were identified, these were combined by fixed effects meta-analysis, unless there was strong evidence of between-study heterogeneity (Cochran Q P < .001), in which case they were kept separate.

Statistical Analysis

We combined summary data across SNPs into a single instrument, using maximum likelihood to estimate the slope of the relationship between βGD and βGP and a variance-covariance matrix to make allowance for linkage disequilibrium between SNPs,28 where βGD is the change in disease log odds or risk factor levels per copy of the effect allele, and βGP is the SD change in telomere length per copy of the effect allele (see eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1 for technical details). The slope from this approach can be interpreted as the log OR for binary outcomes, or the unit change for continuous risk factors, per SD change in genetically increased telomere length. P values for heterogeneity among SNPs in the estimated associations of genetically increased telomere length with disease and risk factors were estimated by likelihood ratio tests.28 Associations between genetically increased telomere length and continuous risk factors were transformed into SD units. For 5 secondary disease outcomes where only a single SNP was available for analysis, we estimated associations using the Wald ratio: βGD/βGP, with standard errors approximated by the delta method.29

Inference of causality in the estimated etiological associations between telomere length and disease depends on satisfaction of Mendelian randomization assumptions (eFigure 7 in Supplement 1; also see eTable 5 in Supplement 1 for a glossary of terms).30,31 The assumptions are that (1) the selected SNPs are associated with telomere length; (2) the selected SNPs are not associated with confounders; and (3) the selected SNPs are associated with disease exclusively through their effect on telomere length. If these assumptions are satisfied, the selected SNPs are valid instrumental variables, and their association with disease can be interpreted as a causal effect of telomere length. We modeled the impact of violations of these assumptions through 2 sets of sensitivity analyses: a weighted median function32 and MR-Egger regression (see eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1 for technical details).30 We restricted our sensitivity analyses to diseases showing the strongest evidence of association with genetically increased telomere length (defined as Bonferroni P ≤ .05).

We used meta-regression to appraise potential sources of heterogeneity in our findings for cancer. The association of genetically increased telomere length with the log odds of cancer was regressed on cancer incidence, survival time, and median age at diagnosis (downloaded from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results [SEER] Program33), and tissue-specific rates of stem cell division from Tomasetti and Vogelstein.34 As the downloaded cancer characteristics from SEER correspond to the United States population, 77% of which was of white ancestry in 2015,35 the meta-regression analyses excluded genetic studies conducted in East Asian populations.

All analyses were performed in R, version 3.1.2,36 and Stata release 13.1 (StataCorp LP). P values were 2-sided, and evidence of association was declared at P < .05. Where indicated, Bonferroni corrections were used to make allowance for multiple testing, although this is likely to be overly conservative given the nonindependence of many of the outcomes tested.

Results

We selected 16 SNPs as instruments for telomere length (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1 and Table 1). The selected SNPs correspond to 10 independent genomic regions that collectively account for 2% to 3% of the variance in leukocyte telomere length, which would be equivalent to an F statistic of 18 to 28 in the sample used to define the instruments (Table 1). This indicates that the genetic instrument constructed from these 10 independent genomic regions is strongly associated with telomere length (details in eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1).37 Summary data for the genetic instruments were available for 83 noncommunicable diseases, corresponding to 420 081 cases (median, 2526 per disease), 1093105 controls (median, 6789 per disease), and 44 risk factors (eFigure 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 1; Table 2). The median number of SNPs available across diseases was 11 (minimum, 1; maximum, 13) and across risk factors was 12 (minimum, 11; maximum, 13). Of the 83 diseases, 56 were classified as primary outcomes and 27 as secondary outcomes (Table 2; eFigure 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 1). For 9 of the 83 noncommunicable diseases, additional summary data were available from 10 independent studies for replication analyses, corresponding to 40 465 cases (median, 1416 per disease) and 52 306 controls (median, 3537 per disease) (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

Table 1. Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms Associated With Telomere Length.

| SNP | Chr | Pos | Gene | EA | OA | EAFa | βa | SEa | P Valuea | Pheta | No. of Studiesa | Sample Sizea | Discovery P Value | Variance Explained, % | Discovery Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs11125529 | 2 | 54248729 | ACYP2 | A | C | 0.16 | 0.065 | 0.012 | 6.06 × 10−3 | 0.313 | 6 | 9177 | 8.00 × 10−10 | 0.080 | Codd et al21 |

| rs6772228 | 3 | 58390292 | PXK | T | A | 0.87 | 0.041 | 0.014 | .0497 | 0.77 | 6 | 8630 | 3.91 × 10−10 | 0.200 | Pooley et al17 |

| rs12696304 | 3 | 169763483 | TERC | C | G | 0.74 | 0.090 | 0.011 | 5.41 × 10−8 | 0.651 | 6 | 9012 | 4.00 × 10−14 | 0.319 | Codd et al22 |

| rs10936599 | 3 | 169774313 | TERC | C | T | 0.76 | 0.100 | 0.011 | 1.76 × 10−9 | 0.087 | 6 | 9190 | 3.00 × 10−31 | 0.319 | Codd et al21 |

| rs1317082 | 3 | 169779797 | TERC | A | G | 0.71 | 0.097 | 0.011 | 4.57 × 10−9 | 0.029 | 6 | 9176 | 1.00 × 10−8 | 0.319 | Mangino et al18 |

| rs10936601 | 3 | 169810661 | TERC | C | T | 0.74 | 0.087 | 0.011 | 8.64 × 10−8 | 0.433 | 6 | 9150 | 4.00 × 10−15 | 0.319 | Pooley et al17 |

| rs7675998 | 4 | 163086668 | NAF1 | G | A | 0.80 | 0.048 | 0.012 | .01 | 0.077 | 6 | 9161 | 4.35 × 10−16 | 0.190 | Codd et al21 |

| rs2736100 | 5 | 1286401 | TERT | C | A | 0.52 | 0.085 | 0.013 | 2.14 × 10−5 | 0.54 | 4 | 5756 | 4.38 × 10−19 | 0.310 | Codd et al21 |

| rs9419958 | 10 | 103916188 | OBFC1 | T | C | 0.13 | 0.129 | 0.013 | 5.26 × 10−11 | 0.028 | 6 | 9190 | 9.00 × 10−11 | 0.171 | Mangino et al18 |

| rs9420907 | 10 | 103916707 | OBFC1 | C | A | 0.14 | 0.142 | 0.014 | 1.14 × 10−11 | 0.181 | 6 | 9190 | 7.00 × 10−11 | 0.171 | Codd et al21 |

| rs4387287 | 10 | 103918139 | OBFC1 | A | C | 0.14 | 0.120 | 0.013 | 1.40 × 10−9 | 0.044 | 6 | 8541 | 2.00 × 10−11 | 0.171 | Levy et al25 |

| rs3027234 | 17 | 8232774 | CTC1 | C | T | 0.83 | 0.103 | 0.012 | 2.75 × 10−8 | 0.266 | 6 | 9108 | 2.00 × 10−8 | 0.292 | Mangino et al18 |

| rs8105767 | 19 | 22032639 | ZNF208 | G | A | 0.25 | 0.064 | 0.011 | <.001 | 0.412 | 6 | 9096 | 1.11 × 10−9 | 0.090 | Codd et al21 |

| rs412658 | 19 | 22176638 | ZNF676 | T | C | 0.35 | 0.086 | 0.010 | 1.83 × 10−8 | 0.568 | 6 | 9156 | 1.00 × 10−8 | 0.484 | Mangino et al18 |

| rs6028466 | 20 | 39500359 | DHX35 | A | G | 0.17 | 0.058 | 0.013 | .004 | 0.533 | 6 | 9190 | 2.57 × 10−8b | 0.041 | Mangino et al18 and Gu et al20 |

| rs755017 | 20 | 63790269 | ZBTB46 | G | A | 0.17 | 0.019 | 0.0129 | .34 | 0.757 | 5 | 8026 | 6.71 × 10−9 | 0.090 | Codd et al21 |

Abbreviations: β, standard deviation change in telomere length per copy of the effect allele; Chr, chromosome; EA, effect allele; EAF, EA frequency; OA, other allele; Phet, P value for between-study heterogeneity in association between SNP and telomere length; Pos, base-pair position (GRCh38.p3); SE, standard error; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Summary data from Mangino et al.18

Table 2. Study Characteristics for Primary Noncommunicable Diseases.

| Disease | Cases, No. | Controls, No. | SNPs, No. | Statistical Power | Population | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | ||||||

| Bladder cancer | 1601 | 1819 | 10 | 0.62 | EUR | NBCS38 |

| Breast cancer | 48 155 | 43 612 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | BCAC17,39 |

| Estrogen receptor negative | 7465 | 42 175 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | BCAC17,39 |

| Estrogen receptor positive | 27 074 | 41 749 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | BCAC17,39 |

| Colorectal cancer | 14 537 | 16 922 | 9 | 1.00 | EUR | CORECT/GECCO40,41 |

| Endometrial cancer | 6608 | 37 925 | 12 | 1.00 | EUR | ECAC42,43 |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 1942 | 2111 | 11 | 0.64 | EA | Abnet et al44 |

| Glioma | 1130 | 6300 | 12 | 0.72 | EUR | Wrensch et al45 and Walsh et al46 |

| Head and neck cancer | 2082 | 3477 | 12 | 1.00 | EUR | McKay et al47 |

| Kidney cancer | 2461 | 5081 | 12 | 0.99 | EUR | KIDRISK48 |

| Lung cancer | 11 348 | 15 861 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | ILCCO49 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 3442 | 14 894 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | ILCCO49 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 3275 | 15 038 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | ILCCO49 |

| Skin cancer | ||||||

| Melanoma | 12 814 | 23 203 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | MC50 |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 3361 | 11 518 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | NHS/HPFS51 |

| Neuroblastoma | 2101 | 4202 | 12 | 0.87 | EUR | Diskin52 |

| Ovarian cancer | 15 397 | 30 816 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | OCAC17,53 |

| Clear cell | 1016 | 30 816 | 13 | 0.76 | EUR | OCAC17,53 |

| Endometrioid | 2154 | 30 816 | 13 | 0.98 | EUR | OCAC17,53 |

| Mucinous | 1643 | 30 816 | 13 | 0.94 | EUR | OCAC17,53 |

| Serous invasive | 9608 | 30 816 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | OCAC17,53 |

| Serous low malignant potential | 972 | 30 816 | 13 | 0.73 | EUR | OCAC17,53 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 5105 | 8739 | 12 | 1.00 | EUR | PanScan (incl. EPIC)54 |

| Prostate cancer | 22 297 | 22 323 | 11 | 1.00 | EUR | PRACTICAL55,56 |

| Testicular germ-cell cancer | 986 | 4946 | 11 | 0.52 | EUR | Turnbull et al57 and Rapley et al58 |

| Autoimmune/Inflammatory Diseases | ||||||

| Alopecia areata | 2332 | 5233 | 7 | 0.60 | EUR | Betz59 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 10 788 | 30 047 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | EAGLE60 |

| Celiac disease | 4533 | 10 750 | 3 | 0.82 | EUR | Dubois61 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | ||||||

| Crohn disease | 5956 | 14 927 | 11 | 1.00 | EUR | IIBDGC62 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 6968 | 20 464 | 12 | 1.00 | EUR | IIBDGC62 |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 1866 | 14 786 | 11 | 0.87 | EUR | Thompson et al63a |

| Multiple sclerosis | 14 498 | 24 091 | 3 | 1.00 | EUR | IMSGC64 |

| Aggressive periodontitis | 888 | 6789 | 13 | 0.63 | EUR | Schaefer et al65 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 5538 | 20 163 | 11 | 1.00 | EUR | Stahl et al66 |

| Cardiovascular Diseases | ||||||

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 4972 | 99 858 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | AC67–72 |

| Coronary heart disease | 22 233 | 64 762 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | CARDIoGRAM73 |

| Heart failure | 2526 | 20 926 | 13 | 0.99 | EUR | CHARGE-HF74 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 2963 | 5503 | 12 | 0.96 | EUR | METASTROKE/ISGC75 |

| Ischemic stroke | 12 389 | 62 004 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | METASTROKE/ISGC76,77 |

| Large-vessel disease | 2167 | 62 004 | 13 | 0.99 | EUR | METASTROKE/ISGC76,77 |

| Small-vessel disease | 1894 | 62 004 | 13 | 0.97 | EUR | METASTROKE/ISGC76 |

| Cardioembolic disease | 2365 | 62 004 | 13 | 0.99 | EUR | METASTROKE/ISGC76 |

| Sudden cardiac arrest | 3954 | 21 200 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | Unpublished |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Type 1 | 7514 | 9045 | 6 | 0.95 | EUR | T1DBase78,79 |

| Type 2 | 10 415 | 53 655 | 11 | 1.00 | EUR | DIAGRAM80 |

| Eye Disease | ||||||

| Age-related macular degeneration | 7473 | 51 177 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | AMD Gene81 |

| Retinopathy | 1122 | 18 289 | 12 | 0.75 | EUR | Jensen et al82 |

| Lung Disease | ||||||

| Asthma | 13 034 | 20 638 | 4 | 1.00 | EUR | GABRIEL/Ferreira et al83,84 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2812 | 2534 | 12 | 0.85 | EUR | COPDGene85 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 1616 | 4683 | 9 | 0.60 | EUR | Fingerlin86 |

| Neurological/Psychiatric Disease | ||||||

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 6100 | 7125 | 12 | 1.00 | EUR | SLAGEN/ALSGEN87 |

| Alzheimer disease | 17 008 | 37 154 | 12 | 1.00 | EUR | IGAP88 |

| Anorexia nervosa | 2907 | 14 860 | 9 | 0.93 | EUR | GCAN89 |

| Autism | 4949 | 5314 | 7 | 0.82 | EUR | PGC90 |

| Bipolar disorder | 7481 | 9250 | 9 | 1.00 | EUR | PGC91 |

| Major depressive disorder | 9240 | 9519 | 8 | 0.99 | EUR | PGC92 |

| Schizophrenia | 35 476 | 46 839 | 12 | 1.00 | EUR | PGC93 |

| Tourette syndrome | 1177 | 4955 | 13 | 0.74 | EUR | TICG/TSAICG94 |

| Other | ||||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 5807 | 56 430 | 13 | 1.00 | EUR | CKDGen95 |

| Endometriosis | 4604 | 9393 | 11 | 1.00 | Mix | Nyholt et al96 |

Abbreviations: EA, East Asian; EUR, European; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Study acronyms: AC, the Aneurysm Consortium; ALSGEN, the International Consortium on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Genetics; AMD Gene, Age-related Macular Degeneration Gene Consortium; BCAC, Breast Cancer Association Consortium; CARDIoGRAM, Coronary ARtery DIsease Genome wide Replication and Meta-analysis; CHARGE-HF, Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Consortium – Heart Failure Working Group; COPDGene, The Genetic Epidemiology of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CKDGen, Chronic Kidney Disease Genetics consortium; CORECT, ColoRectal Transdisciplinary Study; DIAGRAM, DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis; EAGLE, EArly Genetics & Lifecourse Epidemiology Eczema Consortium (excluding 23andMe); ECAC, Endometrial Cancer Association Consortium; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study; GABRIEL, Multidisciplinary Study to Identify the Genetic and Environmental Causes of Asthma in the European Community; GCAN, Genetic Consortium for Anorexia Nervosa; GECCO, Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium; IGAP, International Genomics of Alzheimer Project; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-Up Study; ILCCO, International Lung Cancer Consortium; IMSGC, International Multiple Sclerosis Genetic Consortium; IIBDGC, International Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium; KIDRISK, Kidney cancer consortium; MC, the melanoma meta-analysis consortium; METASTROKE/ISGC, METASTROKE project of the International Stroke Genetics Consortium; NBCS, Nijmegen Bladder Cancer Study; NHS, Nurses' Health Study; OCAC, Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium; PanScan, Pancreatic Cancer Cohort Consortium; PGC, Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; PRACTICAL, Prostate Cancer Association Group to Investigate Cancer Associated Alterations in the Genome; SLAGEN, Italian Consortium for the Genetics of Ayotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; TIDBase, type 1 diabetes database; TICG (Tourette International Collaborative-Genetics); TSAICG (Tourette Syndrome Association International Consortium for Genetics).

Plus previously unpublished data.

The results from primary analyses of noncommunicable diseases are presented in Figure 1 and the eTable in Supplement 2; results from secondary analyses of risk factors and diseases with low a priori power are presented in eFigures 2, 5, and 6 in Supplement 1. Genetically increased telomere length was associated with higher ORs (95% CIs) of disease for 9 of 22 primary cancers (P < .05): glioma (5.27 [3.15-8.81]), endometrial cancer (1.31 [1.07-1.61]), kidney cancer (1.55 [1.08-2.23]), testicular germ-cell cancer (1.76 [1.02-3.04]), melanoma (1.87 [1.55-2.26]), bladder cancer (2.19 [1.32-3.66]), neuroblastoma (2.98 [1.92-4.62]), lung adenocarcinoma (3.19 [2.40-4.22]) and serous low-malignancy-potential (LMP) ovarian cancer (4.35 [2.39-7.94]) (Figure 1). The associations were, however, highly variable across cancer types, varying from an OR (95% CI) of 0.86 (0.57-1.30) for head and neck cancer to 5.27 (3.15-8.81) for glioma. Substantial variability was also observed within tissue sites. For example, the OR (95% CI) for lung adenocarcinoma was 3.19 (2.40-4.22) compared with 1.07 (0.82-1.39) for squamous cell lung cancer. For serous LMP ovarian cancer, the OR (95% CI) was 4.35 (2.39-7.94) compared with 1.21 (0.87-1.68) for endometrioid ovarian cancer, 1.12 (0.94-1.34) for serous invasive ovarian cancer, 1.04 (0.66-1.63) for clear-cell ovarian cancer, and 1.04 (0.73-1.47) for mucinous ovarian cancer. The strongest evidence of association was observed for glioma, lung adenocarcinoma, neuroblastoma, and serous LMP ovarian cancer (Figure 1). Results for glioma and bladder cancer showed evidence for replication in independent data sets (independent data sets were not available for other cancers) (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1).

Figure 1. The Association Between Genetically Increased Telomere Length and Odds of Primary Noncommunicable Diseases.

COPD indicates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ER, estrogen receptor; LMP, low malignancy potential; NA, not applicable; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

a P value for association between genetically increased telomere length and disease from maximum likelihood.

b P value for heterogeneity among SNPs within the instrument.

c The effect estimate for heart failure is a hazard ratio (all others are odds ratios).

Genetically increased telomere length was associated with lower ORs (95% CIs) of disease for 6 of 32 primary non-neoplastic diseases (P < .05): coronary heart disease (0.78 [0.67-0.9]), abdominal aortic aneurysm (0.63 [0.49-0.81]), Alzheimer disease (0.84 [0.71-0.98]), celiac disease (0.42 [0.28-0.61]), interstitial lung disease (0.09 [0.05-0.15]) and type 1 diabetes (0.71 [0.51-0.98]) (Figure 1). The strongest evidence of association was observed for coronary heart disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, celiac disease, and interstitial lung disease (Figure 1). The associations with coronary heart disease and interstitial lung disease showed evidence for replication in independent data sets (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1).

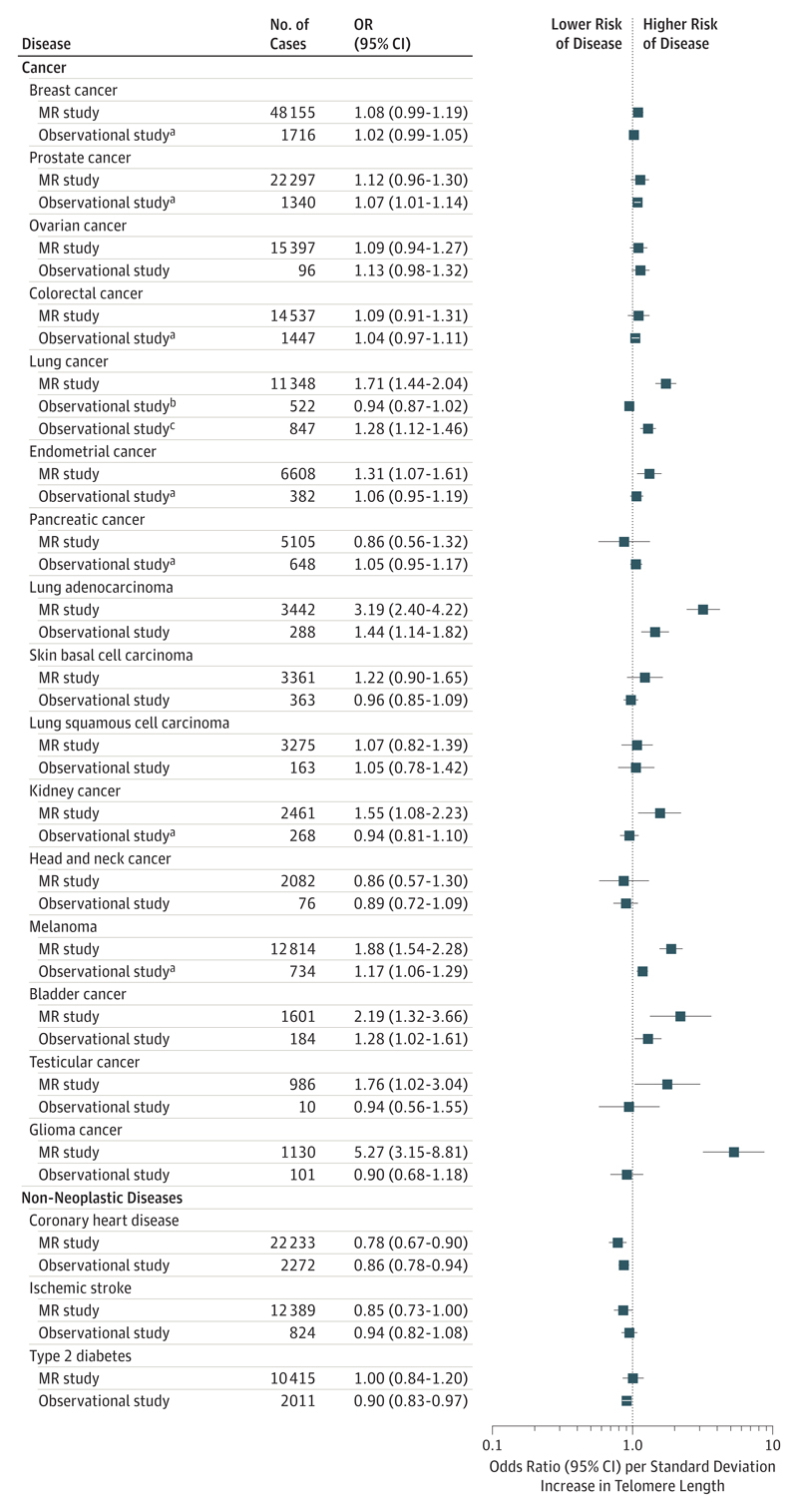

Our genetic findings were generally similar in direction and magnitude to estimates based on observational prospective studies of leukocyte telomere length and disease (Figure 2).10,97 Our genetic estimates for lung adenocarcinoma, melanoma, kidney cancer, and glioma were, however, stronger than the observational estimates.

Figure 2. Comparison of the Present Mendelian Randomization (MR) Study and Prospective Observational Studies of the Association Between Telomere Length and Disease.

Search strategy and characteristics for observational studies are described in eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 1.

a From fixed-effects meta-analysis of independent observational studies described in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

b From the combination of Copenhagen City Heart Study (CCHS) and Copenhagen General Population Study (CGPS).10

c From the combination of Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO), Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study (ATBC), and Shanghai Women's Health Study (SWHS).97

In sensitivity analyses, we appraised the potential impact of confounding by pleiotropic pathways on our results. Associations estimated by the weighted median and MR-Egger were broadly similar to the main results for glioma, lung adenocarcinoma, serous LMP ovarian cancer, neuroblastoma, abdominal aortic aneurysm, coronary heart disease, and interstitial lung disease (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1). We found little evidence for the presence of pleiotropy, as indicated by the MR-Egger intercept test (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1). The MR-Egger analyses were, however, generally underpowered, as reflected by the wide confidence intervals in the estimated odds ratios (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1).

In meta-regression analyses, we observed that genetically increased telomere length tended to be more strongly associated with rarer cancers and cancers at tissue sites with lower rates of stem cell division (Figure 3). The associations showed little evidence of varying by percentage survival 5 years after diagnosis or median age at diagnosis.

Figure 3. The Association Between Genetically Increased Telomere Length and Odds of Cancer as a Function of Selected Characteristics.

A-D, The plotted data show how the strength of the relationship between genetically increased telomere length and cancer varies by the selected characteristic: the R2 statistic indicates how much of the variation between cancers can be explained by the selected characteristic; P values are from meta-regression models; circle sizes are proportional to the inverse of the variance of the log OR. A, Data for average lifetime number of stem cell divisions were downloaded from Tomasetti and Vogelstein.34 B-D, Data for percentage survival 5 years after diagnosis, cancer incidence and median age at diagnosis were downloaded from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.33 Not all cancers had information available for the selected characteristics (hence the number of cancers varies across the subplots). Information was available for 9 cancers for tissue-specific rates of stem cell division, 13 cancers for percentage surviving 5 years after diagnosis, 17 cancers for cancer incidence, and 13 cancers for median age at diagnosis. OR indicates odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

In this report, we show that genetically increased telomere length is associated with increased risk of several cancers and with reduced risk of some non-neoplastic diseases. Given the random distribution of genotypes in the general population with respect to lifestyle and other environmental factors, as well as the fixed nature of germline genotypes, these results should be less susceptible to confounding and reverse causation than those generated by observational studies. Our results could, however, reflect violations of Mendelian randomization assumptions, such as confounding by pleiotropy, population stratification, or ancestry.98 Although we cannot entirely rule out this possibility, the majority of our results persisted in sensitivity analyses that made allowance for violations of Mendelian randomization assumptions. Confounding by population stratification or ancestry is also unlikely, given the adjustments made for ancestry in the original disease GWASs (see eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1). Our results are therefore compatible with causality.

Comparison With Previous Studies

Our findings for cancer are generally contradictory to those based on retrospective studies, which tend to report increased risk for cancer in individuals with shorter telomeres.11,12,99–102 The contradictory findings may reflect reverse causation in the retrospective studies, whereby shorter telomeres arise as a result of disease, or of confounding effects, eg, due to case patients being slightly older than controls even in age-matched analyses. Our findings for cancer are generally more consistent with those based on prospective observational studies, which tend to report weak or null associations of longer leukocyte telomeres with overall and site-specific risk of cancer,10–13,97,101,103–121 with some exceptions.122 Our results are also similar to previously reported Mendelian randomization studies of telomere length and risk of melanoma, lung cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and glioma.40,46,123,124 The shape of the association with cancer may not, however, be linear over the entire telomere length distribution. For example, individuals with dyskeratosis congenita, a disease caused by germline loss-of-function mutations in the telomerase component genes TERC and TERT have chronically short telomeres and are at increased risk of some cancers, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and squamous cell carcinomas arising at sites of leukoplakia,125,126 presumably due to increased susceptibility to genome instability and chromosomal end-to-end fusions.127 Our results should therefore be interpreted as reflecting the average association at the population level and may not be generalizable to the extreme ends of the telomere length distribution.

Mechanisms of Association

Our cancer findings are compatible with known biology.127 By limiting the proliferative potential of cells, telomere shortening may serve as a tumor suppressor, and individuals with longer telomeres may be more likely to acquire somatic mutations owing to increased proliferative potential.127 Rates of cell division are, however, highly variable among tissues,34 and thus the relative gain in cell proliferative potential, conferred by having longer telomeres, may also be highly variable across tissues. This could explain the approximately 6-fold variation in ORs observed across cancer types in the present study as well as the tendency of our results to be stronger at tissue sites with lower rates of stem cell division. For example, the association was strongest for glioma (OR, 5.27) and comparatively weak for colorectal cancer (OR, 1.09), and the rates of stem cell division in the tissues giving rise to these cancers differ by several orders of magnitude. In neural stem cells, which give rise to gliomas, the number of divisions is about 270 million, and for colorectal stem cells it is about 1.2 trillion over the average lifetime of an individual.34 The observation that genetically increased telomere length was more strongly associated with rarer cancers potentially reflects the same mechanism, since rarer cancers also tend to show lower rates of stem cell division.34 For example, the incidence of glioma per 100 000 people per year in the United States is 0.4, and for colorectal cancer it is 42.4.33

The inverse associations observed for some nonneoplastic diseases may reflect the impact of telomere shortening on tissue degeneration and an evolutionary trade-off for greater resistance to cancer at the cost of greater susceptibility to degenerative diseases, particularly cardiovascular diseases.128,129

Clinical Relevance of Findings

Our findings suggest that potential clinical applications of telomere length, eg, as a tool for risk prediction or as an intervention target for disease prevention, may be subject to a trade-off in risk between cancer and non-neoplastic diseases. For example, a number of companies have been established that offer telomere length measurement services to the public (via a requesting physician) under the claim that shorter telomeres are a general indicator of poorer health status and older biological age and that such information can be used to motivate healthy lifestyle choices in individuals. However, the conflicting direction of association between telomere length and risk of cancer and non-neoplastic diseases indicated by our findings suggests that such services to the general public may be premature.

Study Limitations

Our study is subject to some limitations, in addition to the Mendelian randomization assumptions already considered. First, our method assumes that the magnitude of the association between SNPs and telomere length is consistent across tissues. Second, our study assumed a linear shape of association between telomere length and disease risk, whereas the shape could be “J” or “U” shaped.104,117,125 Third, our results assume that the samples used to define the genetic instrument for telomere length18 and the various samples used to estimate the SNP-disease associations are representative of the same general population, practically defined as being of similar ethnicity, age, and sex distribution.130 This assumption would, for example, not apply in the case of the SNP-disease associations derived from East Asian or pediatric populations. Generally speaking, violation of these assumptions could bias the magnitude of the association between genetically increased telomere length and disease but would probably not increase the likelihood of false positives (ie, incorrectly inferring an association when none exists).131 Our results should therefore remain informative for the direction and broad magnitude of the average association at the population level, even in the presence of such violations. Fourth, we cannot rule out chance in explaining some of the weaker findings. Fifth, our results may not be fully representative of noncommunicable diseases (since not all studies shared data, and our analyses were underpowered for the secondary disease outcomes). The diseases represented in our primary analyses probably account for more than 60% of all causes of death in American adults.132

Conclusions

It is likely that longer telomeres increase risk for several cancers but reduce risk for some non-neoplastic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases. Further research is required to resolve whether telomere length is a useful predictor of risk that can help guide therapeutic interventions, to clarify the shape of any dose-response relationships, and to characterize the nature of the association in population subgroups.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

What is the causal relevance of telomere length for risk of cancer and non-neoplastic diseases?

Findings

In this Mendelian randomization study, genetically longer telomeres were associated with higher odds of disease for 9 of 22 primary cancers tested but with reduced odds of disease for 6 of 32 primary non-neoplastic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases.

Meaning

It is likely that longer telomeres increase risk for several cancers but reduce risk for some non-neoplastic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases. This trade-off in risk should be carefully considered in any diagnostic, prognostic, or therapeutic applications based on telomere length.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by CRUK grant number C18281/A19169 (the Integrative Cancer Epidemiology Programme). Dr Haycock is supported by CRUK Population Research Postdoctoral Fellowship C52724/A20138. The MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit is supported by grants MC_UU_12013/1 and MC_UU_12013/2. Dr Martin is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the Bristol Nutritional Biomedical Research Unit and the University of Bristol. Dr Timpson is supported by Medical Research Council MC_UU_12013/3.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding institutions had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions: We gratefully acknowledge all the studies and databases that made GWAS summary data available (see Supplement 1 for detailed acknowledgments). We also thank Sharon J. Diskin, PhD, Department of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, who extracted neuroblastoma association study results and provided summary and metadata to support this study. She received no compensation for her contributions.

The Telomeres Mendelian Randomization Collaboration

Philip C. Haycock, PhD; Stephen Burgess, PhD; Aayah Nounu, BSc; Jie Zheng, PhD; George N. Okoli, MBBS, MSc; Jack Bowden, PhD; Kaitlin Hazel Wade, PhD; Nicholas J. Timpson, PhD; David M. Evans, PhD; Peter Willeit, MD, PhD; Abraham Aviv, MD; Tom R. Gaunt, BSc, PhD; Gibran Hemani, PhD; Massimo Mangino, PhD; Hayley Patricia Ellis, BSc; Kathreena M. Kurian, MD; Karen A. Pooley, PhD; Rosalind A. Eeles, PhD; Jeffrey E. Lee, MD; Shenying Fang, MD, PhD; Wei V. Chen, MS; Matthew H. Law, PhD; Lisa M. Bowdler, BASc; Mark M. Iles, PhD; Qiong Yang, PhD; Bradford B. Worrall, MD, MSc; Hugh Stephen Markus, DM; Rayjean J. Hung, PhD; Chris I. Amos, PhD; Amanda B. Spurdle, PhD; Deborah J. Thompson, PhD; Tracy A. O'Mara, PhD; Brian Wolpin, MD, MPH; Laufey Amundadottir, PhD; Rachael Stolzenberg-Solomon, PhD, MPH, RD; AntoniaTrichopoulou, MD, PhD; N. Charlotte Onland-Moret, PhD; Eiliv Lund, PhD; Eric J. Duell, PhD; Federico Canzian, PhD; Gianluca Severi, PhD; Kim Overvad, PhD; Marc J. Gunter, PhD; Rosario Tumino, PhD; Ulrika Svenson, MD, PhD; Andre van Rij, MD, FRACS; Annette F. Baas, PhD; Matthew J. Bown, MB BCh, MD; Nilesh J. Samani, FMedSci; Femke N.G. van t'Hof, MD; Gerard Tromp, PhD, FAHA; Gregory T. Jones, PhD; Helena Kuivaniemi, MD, PhD, FAHA; James R. Elmore, MD; Mattias Johansson, PhD; James Mckay, PhD; Ghislaine Scelo, PhD; Robert Carreras-Torres, PhD; Valerie Gaborieau, BTEC; Paul Brennan, PhD; Paige M. Bracci, PhD; Rachel E. Neale, PhD; Sara H. Olson, PhD; Steven Gallinger, MD, MSc; Donghui Li, PhD; Gloria M. Petersen, PhD; Harvey A. Risch, MD, PhD; Alison P. Klein, PhD, MHS; Jiali Han, PhD; Christian C. Abnet, PhD, MPH; Neal D. Freedman, PhD, MPH; Philip R. Taylor, MD, ScD; John M. Maris, MD; Katja K. Aben, PhD; Lambertus A. Kiemeney, PhD; Sita H. Vermeulen, PhD; John K. Wiencke, PhD; Kyle M. Walsh, PhD; Margaret Wrensch, PhD, MPH; Terri Rice, MPH; Clare Turnbull, MD, PhD; Kevin Litchfield, MRes; Lavinia Paternoster, PhD; Marie Standl, PhD; Gonçalo R. Abecasis, DPhil; John Paul SanGiovanni, ScD; Yong Li, MD; Vladan Mijatovic, PhD; Yadav Sapkota, PhD; Siew-Kee Low, PhD; Krina T. Zondervan, DPhil; Grant W. Montgomery, PhD; Dale R. Nyholt, PhD; David A. van Heel, MD, PhD; Karen Hunt, PhD; Dan E. Arking, PhD; Foram N. Ashar, BS; Nona Sotoodehnia, MD, MPH; Daniel Woo, PhD; Jonathan Rosand, MD, MSc; Mary E. Comeau, MA; W. Mark Brown, MA; Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD; John E. Hokanson, PhD; Michael H. Cho, MD; Jennie Hui, PhD; Manuel A. Ferreira, PhD; Philip J. Thompson, FRACP; Alanna C. Morrison, PhD; Janine F. Felix, MD, PhD; Nicholas L. Smith, PhD; Angela M Christiano, PhD; Lynn Petukhova, PhD; Regina C. Betz, MD; Xing Fan, PhD; Xuejun Zhang, PhD; Caihong Zhu, PhD; Carl D. Langefeld, PhD; Susan D. Thompson, PhD; Feijie Wang, MSc; Xu Lin, PhD; David A. Schwartz, MD; Tasha Fingerlin, PhD; Jerome I. Rotter, MD; Mary Frances Cotch, PhD; Richard A. Jensen, OD, PhD; Matthias Munz, BSc, MSc; Henrik Dommisch, MD; Arne S. Schaefer, PhD; Fang Han, MD; Hanna M. Ollila, PhD; Ryan P. Hillary, BS; Omar Albagha, PhD; Stuart H. Ralston, MD; Chenjie Zeng, MPH; Wei Zheng, MD, PhD, MPH; Xiao-Ou Shu, MD, PhD; Andre Reis, MD; Steffen Uebe, PhD; Ulrike Hüffmeier, MD; Yoshiya Kawamura, MD, PhD; Takeshi Otowa, MD, PhD; Tsukasa Sasaki, MD, PhD; Martin Lloyd Hibberd, PhD; Sonia Davila, PhD; Gang Xie, MD, PhD; Katherine Siminovitch, MD; Jin-Xin Bei, PhD; Yi-Xin Zeng, MD, PhD; Asta Försti, PhD; Bowang Chen, PhD; Stefano Landi, PhD; Andre Franke, PhD; Annegret Fischer, PhD; David Ellinghaus, PhD; Carlos Flores, PhD; Imre Noth, MD; Shwu-Fan Ma, PhD; Jia Nee Foo, PhD; Jianjun Liu, PhD; Jong-Won Kim, MD, PhD; David G. Cox, PhD; Olivier Delattre, MD, PhD; Olivier Mirabeau, PhD; Christine F. Skibola, PhD; Clara S. Tang, PhD; Merce Garcia-Barcelo, MSc, PhD; Kai-Ping Chang, MD, PhD; Wen-Hui Su, PhD; Yu-Sun Chang, PhD; Nicholas G. Martin, PhD; Scott Gordon, PhD; Tracey D. Wade, PhD; Chaeyoung Lee, PhD; Michiaki Kubo, MD, PhD; Pei-Chieng Cha, PhD; Yusuke Nakamura, MD, PhD; Daniel Levy, MD; Masayuki Kimura, PhD; Shih-Jen Hwang, PhD; Steven Hunt, PhD; Tim Spector, MD, PhD; Nicole Soranzo, PhD; Ani W. Manichaikul, PhD; R. Graham Barr, MD, DrPH; Bratati Kahali, PhD; Elizabeth Speliotes, MD, PhD; Laura M. Yerges-Armstrong, PhD; Ching-Yu Cheng, MD, PhD; Jost B. Jonas, MD; Tien Yin Wong, MBBS, PhD; Isabella Fogh, PhD; Kuang Lin, PhD; John F. Powell, PhD; Kenneth Rice, PhD; Caroline L. Relton, PhD, BSc, PGCE; Richard M. Martin, BMedSci, BM BS, MSc, PhD; George Davey Smith, DSc.

Affiliations of The Telomeres Mendelian Randomization Collaboration

MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, University of Bristol, Bristol, England (Haycock, Nounu, J. Zheng, Bowden, K. H. Wade, Timpson, Evans, Gaunt, Hemani, Paternoster, Relton, R. M. Martin, Davey Smith); School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, England (Haycock, Nounu, J. Zheng, Okoli, Bowden, K. H. Wade, Timpson, Evans, Gaunt, Hemani, Paternoster, Relton, R. M. Martin, Davey Smith); Department of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England (Burgess, Willeit); University of Queensland Diamantina Institute, Translational Research Institute, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia (Evans); Department of Neurology, Innsbruck Medical University, Austria (Willeit); Center of Human Development and Aging, Department of Pediatrics, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey (Aviv, Kimura); Department of Twin Research and Genetic Epidemiology, King's College London, London England (Mangino, Spector); NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Guy's and St Thomas' Foundation Trust, London, England (Mangino); Brain Tumour Research Group, Institute of Clinical Neuroscience, Learning and Research Building, Southmead Hospital, University of Bristol (Ellis, Kurian); Centre for Cancer Genetic Epidemiology, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England (Pooley, D. J. Thompson); The Institute of Cancer Research and Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, England (Eeles, Turnbull); Department of Surgical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston (J. E. Lee, Fang); Department of Clinical Applications & Support, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston (W. V. Chen); Statistical Genetics, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia (Law); QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia (Bowdler, Neale, Sapkota, Montgomery, Nyholt, Ferreira, N. G. Martin, Gordon); Section of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Leeds Institute of Cancer and Pathology, University of Leeds, Leeds, England (Iles); Department of Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts (Yang); Departments of Neurology and Public Health Sciences, University of Virginia Charlottesville, Virginia (Worrall); Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, England (Markus); Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute of Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (Hung, Gallinger, Xie, Siminovitch); Division of Epidemiology, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (Hung); Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire (Amos); Genetics and Computational Biology Division, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia (Spurdle, O'Mara); Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts (Wolpin); Laboratory of Translational Genomics, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (Amundadottir); Metabolic Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Maryland (Stolzenberg-Solomon); Hellenic Health Foundation, Athens, Greece (Trichopoulou); WHO Collaborating Center for Nutrition and Health, Unit of Nutritional Epidemiology and Nutrition in Public Health, Department of Hygiene, Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, University of Athens Medical School, Athens, Greece (Trichopoulou); Department of Epidemiology, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands (Onland-Moret); Institute of Community Medicine, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromso, Norway (Lund); Unit of Nutrition and Cancer, Cancer Epidemiology Research Program, Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL), Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO), L'Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain (Duell); Genomic Epidemiology Group, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany (Canzian); Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris-Sud, UVSQ, CESP, INSERM, Villejuif, France (Severi); Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France (Severi); Human Genetics Foundation (HuGeF), Torino, Italy (Severi); Cancer Council Victoria and University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia (Severi); Department of Public Health, Section for Epidemiology, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark (Overvad); School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, England (Gunter); Cancer Registry, Azienda Ospedaliera “Civile M.P. Arezzo,” Ragusa, Italy (Tumino); Department of Medical Biosciences, Umea University, Umea, Sweden (Svenson); Surgery Department, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand (van Rij, Jones); Department of Genetics, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands (Baas); Department of Cardiovascular Sciences and the NIHR Leicester, Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit, University of Leicester, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, England (Bown, Samani); Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Brain Center Rudolf Magnus, University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands. (van t'Hof); Division of Molecular Biology and Human Genetics, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg, South Africa (Tromp, Kuivaniemi); The Sigfried and Janet Weis Center for Research, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pennsylvania (Tromp, Kuivaniemi); Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pennsylvania (Elmore); Genetic Epidemiology Group, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France (Johansson, Scelo, Carreras-Torres, Gaborieau, Brennan); Genetic Cancer Susceptibility Group, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France (Mckay); Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California San Francisco (Bracci); Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York (Olson); Department of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston (D. Li); Department of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota (Petersen); Yale School of Public Health, Yale School of Medicine, and Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Connecticut (Risch); Departments of Oncology, Pathology and Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland (Klein); Department of Epidemiology, Fairbanks School of Public Health, Indiana University, Indianapolis (J. Han); Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Cancer Center, Indianapolis (J. Han); Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Maryland (Abnet, Freedman, Taylor); Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (Maris); Radboud University Medical Center, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Nijmegen, The Netherlands (Aben, Kiemeney, Vermeulen); Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization, Utrecht, The Netherlands (Aben); Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California (Wiencke, Walsh, Wrensch, T. Rice); Institute of Human Genetics, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California (Wiencke, Walsh, Wrensch); William Harvey Research Institute, Queen Mary University, London, England (Turnbull); Division of Genetics and Epidemiology, The Institute of Cancer Research, London, England (Litchfield); Institute of Epidemiology I, Helmholtz Zentrum München - German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Germany (Standl); Department of Biostatistics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (Abecasis); National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Laboratory of Membrane Biophysics and Biochemistry, Section on Nutritional Neuroscience, Bethesda, Maryland (SanGiovanni); Department of Biochemistry and Molecular and Cellular Biology, Georgetown School of Medicine, Washington, DC (SanGiovanni); Division of Genetic Epidemiology, Institute for Medical Biometry and Statistics, Faculty of Medicine, and Medical Centre, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany (Y. Li); Department of Life and Reproduction Sciences, University of Verona, Verona, Italy (Mijatovic); Laboratory of Statistical Analysis, Centre for Integrative Medical Sciences, The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (RIKEN), Yokohama, Japan (Low); Genetic and Genomic Epidemiology Unit, Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford, Oxford, England (Zondervan); Nuffield Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England (Zondervan); Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia (Nyholt); Blizard Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London E1 2AT, England (van Heel, K. Hunt); McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland (Arking, Ashar); Division of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington (Sotoodehnia); University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Department of Neurology, Cincinnati, Ohio (Woo); Massachusetts General Hospital, Neurology, Center for Human Genetic Research, Boston, Massachusetts (Rosand); Center for Public Health Genomics, Department of Biostatistical Sciences, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (Comeau, Brown, Langefeld); Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Silverman, Cho); Department of Epidemiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado (Hokanson); Busselton Population Medical Research Institute Inc, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth, Australia (Hui); PathWest Laboratory Medicine of Western Australia, Perth, Australia (Hui); School of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia (Hui); School of Population Health, University of WA, Perth, Australia (Hui); The Lung Health Clinic and Institute for Respiratory Health, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia (P. J. Thompson); Department of Epidemiology, Human Genetics, and Environmental Sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston (Morrison); Department of Epidemiology, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (Felix); Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle (Smith); Departments of Dermatology and Genetics & Development, Columbia University, New York, New York (Christiano); Departments of Dermatology and Epidemiology, Columbia University, New York, New York (Petukhova); Institute of Human Genetics, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany (Betz); Institute of Dermatology & Department of Dermatology, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui, China (Fan, Zhang, Zhu); Center for Autoimmune Genomics and Etiology, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Department of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio (S. D. Thompson); Key Laboratory of Nutrition and Metabolism, Institute for Nutritional Sciences, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China (Wang, X. Lin); Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Colorado, Aurora (Schwartz); Department of Biomedical Research, National Jewish Health Hospital, Denver, Colorado (Fingerlin); Institute for Translational Genomics and Population Sciences, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California (Rotter); Departments of Pediatrics and Medicine, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California (Rotter); Epidemiology Branch, Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Applications, Intramural Research Program, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Clinical Research Center, Bethesda, Maryland (Cotch); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle (Jensen); Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle (Jensen); Department of Periodontology and Synoptic Dentistry, Center for Dental and Craniofacial Sciences, Charité - University Medicine Berlin, Berlin, Germany (Munz, Dommisch, Schaefer); Institute for Integrative and Experimental Genomics, University of Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany (Munz); Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Peking University People's Hospital, Beijing, China (F. Han); Stanford University, Center for Sleep Sciences, Palo Alto, California (Ollila, Hillary); Qatar Biomedical Research Institute, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Doha, Qatar (Albagha); Centre for Genomic and Experimental Medicine, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, Scotland (Albagha, Ralston); Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee (C. Zeng, W. Zheng, Shu); Institute of Human Genetics, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany (Reis, Uebe, Hüffmeier); Department of Psychiatry, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan (Kawamura); Department of Neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan (Otowa); Graduate School of Clinical Psychology, Teikyo Heisei University Major of Professional Clinical Psychology, Tokyo, Japan (Otowa); Department of Physical and Health Education, Graduate School of Education, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan (Sasaki); Infectious Diseases, Genome Institute of Singapore, Singapore (Hibberd); Human Genetics, Genome Institute of Singapore, Singapore (Davila); Departments of Medicine, Immunology, Molecular Genetics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (Xie, Siminovitch); Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine, Guangzhou, China (Bei, Y. Zeng); Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China (Y. Zeng); Molecular Genetic Epidemiology, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany (Försti, B. Chen); Center for Primary Health Care Research, Clinical Research Center, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden (Försti); Department of Biology, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy (Landi); University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel, Germany(Franke, Fischer); Instituteof Clinical Molecular Biology, Kiel University, Kiel, Germany (Fischer, Ellinghaus); Research Unit, Hospital Universitario N.S. de Candelaria, Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain (Flores); CIBER de Enfermedades Respiratorias, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain (Flores); Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois (Noth, Ma); Human Genetics, Genome Instituteof Singapore, A*STAR, Singapore (Foo, Liu); Department of Laboratory Medicine and Genetics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan, University School of Medicine, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, South Korea (Kim); Cancer Research Center of Lyon, INSERM U1052, Lyon, France (Cox); Inserm U830, Institut Curie, PSL University, Paris, France (Delattre, Mirabeau); Department of Epidemiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham (Skibola); Department of Surgery, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong (Tang, Garcia-Barcelo); Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Lin-Kou, Taoyuan, Taiwan (K. Chang, Su); Department of Biomedical Sciences, Graduate Institute of Biomedical Sciences, College of Medicine, Molecular Medicine Research Center, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan (Su); Molecular Medicine Research Center, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan (Y. Chang); School of Psychology, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia (T. D. Wade); School of Systems Biomedical Science, Soongsil University, Dongjak-gu, Seoul, South Korea (C. Lee); RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Science, Suehiro-cho, Tsurumi-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan (Kubo); Division of Molecular Brain Science, Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine, Kusunoki-chou, Chuo-ku, Kobe, Japan (Cha); Center for Personalized Therapeutics, The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois (Nakamura); The NHLBI's Framingham Heart Study, Framingham, Massachusetts, Population Sciences Branch of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland (Levy, Hwang); Department of Genetic Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine in Qatar, Doha, Qatar (S. Hunt); Human Genetics, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Genome Campus, Hinxton Cambridge, England (Soranzo); Center for Public Health Genomics, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville (Manichaikul); Department of Medicine and Department of Epidemiology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York (Barr); Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Department of Computational Medicine and Bioinformatics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (Kahali, Speliotes); Department of Medicine, University of Maryland, Baltimore (Yerges-Armstrong); Singapore Eye Research Institute, Singapore National Eye Center, Singapore (Cheng, Wong); Department of Ophthalmology, National University of Singapore and National University Health System, Singapore (Cheng, Wong); Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore (Cheng, Wong); Beijing Instituteof Ophthalmology, Beijing Tongren Eye Center, Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing Ophthalmology and Visual Science Key Laboratory, Beijing, China (Jonas); Department of Ophthalmology, Medical Faculty Mannheim of the Ruprecht-Karls-University Heidelberg, Mannheim, Germany (Jonas); Department of Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, Maurice Wohl Clinical Neuroscience Institute, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London, London, England (Fogh, K. Lin, Powell); Department of Biostatistics, University of Washington, Seattle (K. Rice); University of Bristol/University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust National Institute for Health Research Bristol Nutrition Biomedical Research Unit, Bristol, England (R. M. Martin).

Additional Information

All GWAS summary data used in this study can be found at http://www.mrbase.org.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Haycock had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Haycock, Timpson, Aviv, Amos, Onland-Moret, Severi, Tumino, D Li, Taylor, Woo, Zhu, Schwartz, Y Zeng, Ellinghaus, Y Chang, Jonas, Wong, Relton, Davey Smith.

Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: Haycock, Burgess, Nounu, J Zheng, Okoli, Bowden, K Wade, Timpson, Evans, Willeit, Aviv, Gaunt, Hemani, Mangino, Ellis, Kurian, Pooley, Eeles, J Lee, Fang, W Chen, Law, Bowdler, Iles, Yang, Worrall, Markus, Hung, Amos, Spurdle, D Thompson, O'Mara, Wolpin, Amundadottir, Stolzenberg-Solomon, Trichopoulou, Onland-Moret, Lund, Duell, Canzian, Severi, Overvad, Gunter, Svenson, van Rij, Baas, Bown, Samani, van t'Hof, Tromp, Jones, Kuivaniemi, Elmore, Johansson, Mckay, Scelo, Carreras-Torres, Gaborieau, Brennan, Bracci, Neale, Olson, Gallinger, D Li, Petersen, Risch, Klein, J Han, Abnet, Freedman, Maris, Aben, Kiemeney, Vermeulen, Wiencke, Walsh, Wrensch, T Rice, Turnbull, Litchfield, Paternoster, Standl, Abecasis, SanGiovanni, Y Li, Mijatovic, Sapkota, Low, Zondervan, Montgomery, Nyholt, van Heel, K Hunt, Arking, Ashar, Sotoodehnia, Rosand, Comeau, Brown, Silverman, Hokanson, Cho, Hui, Ferreira, P Thompson, Morrison, Felix, Smith, Christiano, Petukhova, Betz, Fan, Zhang, Langefeld, Susan D Thompson, Wang, X Lin, Schwartz, Fingerlin, Rotter, Cotch, Jensen, Munz, Dommisch, Schaefer, F Han, Ollila, Hillary, Albagha, Ralston, C Zeng, W Zheng, Shu, Reis, Uebe, Hüffmeier, Kawamura, Otowa, Sasaki, Hibberd, Davila, Xie, Siminovitch, Bei, Försti, B Chen, Landi, Franke, Fischer, Ellinghaus, Flores, Noth, Ma, Foo, Liu, Kim, Cox, Delattre, Mirabeau, Skibola, Tang, Garcia-Barcelo, K Chang, Su, Y Chang, N Martin, Gordon, T Wade, C Lee, Kubo, Cha, Nakamura, Levy, Kimura, Hwang, S Hunt, Spector, Soranzo, Manichaikul, Barr, Kahali, Speliotes, Yerges-Armstrong, Cheng, Jonas, Fogh, K Lin, Powell, K Rice, Relton, R Martin.

Drafting of the manuscript: Haycock, Burgess, Timpson, Relton, Davey Smith.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Haycock, Burgess, Nounu, J Zheng, Okoli, Bowden, K Wade, Evans, Willeit, Aviv, Gaunt, Hemani, Mangino, Ellis, Kurian, Pooley, Eeles, J Lee, Fang, W Chen, Law, Bowdler, Iles, Yang, Worrall, Markus, Hung, Amos, Spurdle, D Thompson, O'Mara, Wolpin, Amundadottir, Stolzenberg-Solomon, Trichopoulou, Onland-Moret, Lund, Duell, Canzian, Severi, Overvad, Gunter, Tumino, Svenson, van Rij, Baas, Bown, Samani, van t'Hof, Tromp, Jones, Kuivaniemi, Elmore, Johansson, Mckay, Scelo, Carreras-Torres, Gaborieau, Brennan, Bracci, Neale, Olson, Gallinger, D Li, Petersen, Risch, Klein, J Han, Abnet, Freedman, Taylor, Maris, Aben, Kiemeney, Vermeulen, Wiencke, Walsh, Wrensch, T Rice, Turnbull, Litchfield, Paternoster, Standl, Abecasis, SanGiovanni, Y Li, Mijatovic, Sapkota, Low, Zondervan, Montgomery, Nyholt, van Heel, K Hunt, Arking, Ashar, Sotoodehnia, Woo, Rosand, Comeau, Brown, Silverman, Hokanson, Cho, Hui, Ferreira, P Thompson, Morrison, Felix, Smith, Christiano, Petukhova, Betz, Fan, Zhang, Zhu, Langefeld, Susan D Thompson, Wang, X Lin, Schwartz, Fingerlin, Rotter, Cotch, Jensen, Munz, Dommisch, Schaefer, F Han, Ollila, Hillary, Albagha, Ralston, C Zeng, W Zheng, Shu, Reis, Uebe, Hüffmeier, Kawamura, Otowa, Sasaki, Hibberd, Davila, Xie, Siminovitch, Bei, Y Zeng, Försti, B Chen, Landi, Franke, Fischer, Ellinghaus, Flores, Noth, Ma, Foo, Liu, Kim, Cox, Delattre, Mirabeau, Skibola, Tang, Garcia-Barcelo, K Chang, Su, Y Chang, N Martin, Gordon, T Wade, C Lee, Kubo, Cha, Nakamura, Levy, Kimura, Hwang, S Hunt, Spector, Soranzo, Manichaikul, Barr, Kahali, Speliotes, Yerges-Armstrong, Cheng, Jonas, Wong, Fogh, K Lin, Powell, K Rice, Relton, R Martin, Davey Smith.

Statistical analysis: Haycock, Burgess, J Zheng, Bowden, Evans, Fang, W Chen, Law, Yang, Hung, Amos, D Thompson, Amundadottir, van t'Hof, Jones, Mckay, J Han, Vermeulen, Walsh, Litchfield, Paternoster, Standl, Y Li, Mijatovic, Sapkota, Low, Zondervan, Nyholt, K Hunt, Arking, Ashar, Comeau, Hokanson, Ferreira, Felix, Langefeld, Wang, X Lin, Jensen, Munz, Ollila, Hillary, C Zeng, Kawamura, Hibberd, Davila, B Chen, Flores, Noth, Foo, Cox, N Martin, C Lee, Cha, Hwang, Manichaikul, Kahali, Cheng, K Lin, K Rice, Davey Smith.

Obtaining funding: Haycock, Aviv, Amos, Spurdle, Lund, Overvad, Gunter, van Rij, Johansson, Gallinger, D Li, Petersen, Kiemeney, Wiencke, Wrensch, Zondervan, Montgomery, Nyholt, Rosand, Hokanson, Morrison, Rotter, F Han, Shu, Siminovitch, Bei, T Wade, Kubo, S Hunt, Spector, Speliotes, Relton, R Martin.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Nounu, Okoli, K Wade, Gaunt, Hemani, Kurian, Pooley, J Lee, Law, Markus, Amos, Spurdle, O'Mara, Stolzenberg-Solomon, Duell, Canzian, Overvad, Tumino, Jones, Elmore, Johansson, Carreras-Torres, Gaborieau, Gallinger, D Li, Petersen, J Han, Aben, Wrensch, T Rice, Abecasis, SanGiovanni, Montgomery, Nyholt, van Heel, Woo, Hokanson, Hui, Ferreira, P Thompson, Christiano, Petukhova, Betz, Zhang, Zhu, Rotter, Cotch, Dommisch, W Zheng, Sasaki, Xie, Siminovitch, Bei, Försti, Franke, Fischer, Ellinghaus, Liu, Kim, Delattre, Garcia-Barcelo, Su, Y Chang, Kubo, Kimura, S Hunt, Spector, Soranzo, Jonas.

Study supervision: Haycock, Mangino, Hung, Trichopoulou, Tumino, Johansson, Mckay, Brennan, Kiemeney, Montgomery, Rosand, Silverman, Hokanson, Hui, P Thompson, Smith, Shu, Y Zeng, Kimura, Wong, Relton, R Martin, Davey Smith.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Yerges-Armstrong is a current employee stock-owner at GlaxoSmithKline though the current work was completed while an employee of University of Maryland Baltimore. Dr Worrall is a deputy editorship for the journal Neurology and has received National Institutes of Health funding for sample genotyping. Dr Silverman has received honoraria from Novartis for Continuing Medical Education Seminars and grant and travel support from GlaxoSmithKline. Helena Kuivaniemi has received funding from the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL064310, HL044682), the Pennsylvania Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement program, the Geisinger Clinical Research Fund, the American Heart Association, the Ben Franklin Technology Development Fund of Pennsylvania, and the National Institutes of Health for sample genotyping (U01HG006382). Dr Eeles has received honoraria from the Genitourinary Cancers Symposium organised by American Society of Clinical Oncology. Dr Rotter has received funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL105756), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, CTSI grant UL1TR001881, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Diabetes Research Center grant DK063491 to the Southern California Diabetes Research Center. No other conflicts reported.

References

- 1.Blackburn EH, Epel ES, Lin J. Human telomere biology: a contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science. 2015;350(6265):1193–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samani NJ, van der Harst P. Biological ageing and cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2008;94(5):537–539. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.136010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG. Telomere shortening unrelated to smoking, body weight, physical activity, and alcohol intake: 4,576 general population individuals with repeat measurements 10 years apart. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(3):e1004191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houben JMJ, Moonen HJJ, van Schooten FJ, Hageman GJ. Telomere length assessment: biomarker of chronic oxidative stress? Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44(3):235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchesi V. Risk factors: short telomeres: association with cancer survival and risk. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(5):247. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haycock PC, Heydon EE, Kaptoge S, Butterworth AS, Thompson A, Willeit P. Leucocyte telomere length and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;349(6):g4227. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rode L, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Peripheral blood leukocyte telomere length and mortality among 64,637 individuals from the general population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv074. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao J, Miao K, Wang H, Ding H, Wang DW. Association between telomere length and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weischer M, Nordestgaard BG, Cawthon RM, Freiberg JJ, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Bojesen SE. Short telomere length, cancer survival, and cancer risk in 47102 individuals. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(7):459–468. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma H, Zhou Z, Wei S, et al. Shortened telomere length is associated with increased risk of cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wentzensen IM, Mirabello L, Pfeiffer RM, Savage SA. The association of telomere length and cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(6):1238–1250. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pooley KA, Sandhu MS, Tyrer J, et al. Telomere length in prospective and retrospective cancer case-control studies. Cancer Res. 2010;70(8):3170–3176. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou L, Joyce BT, Gao T, et al. Blood telomere length attrition and cancer development in the Normative Aging Study cohort. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(6):591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welter D, MacArthur J, Morales J, et al. The NHGRI GWAS Catalog, a curated resource of SNP-trait associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D1001–D1006. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burdett T, Hall P, Hastings E, et al. The NHGRI-EBI Catalog of published genome-wide association studies. [Accessed January 15, 2015]; doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1133. http://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Pooley KA, Bojesen SE, Weischer M, et al. A genome-wide association scan (GWAS) for mean telomere length within the COGS project: identified loci show little association with hormone-related cancer risk. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(24):5056–5064. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mangino M, Hwang S-J, Spector TD, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis points to CTC1 and ZNF676 as genes regulating telomere homeostasis in humans. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(24):5385–5394. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prescott J, Kraft P, Chasman DI, et al. Genome-wide association study of relative telomere length. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu J, Chen M, Shete S, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a locus on chromosome 14q21 as a predictor of leukocyte telomere length and as a marker of susceptibility for bladder cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4(4):514–521. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Codd V, Nelson CP, Albrecht E, et al. CARDIoGRAM consortium. Identification of seven loci affecting mean telomere length and their association with disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):422–427 e1-e2. doi: 10.1038/ng.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Codd V, Mangino M, van der Harst P, et al. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Common variants near TERC are associated with mean telomere length. Nat Genet. 2010;42(3):197–199. doi: 10.1038/ng.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Cao L, Li Z, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a locus on TERT for mean telomere length in Han Chinese. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saxena R, Bjonnes A, Prescott J, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in casein kinase II (CSNK2A2) to be associated with leukocyte telomere length in a Punjabi Sikh diabetic cohort. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7(3):287–295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy D, Neuhausen SL, Hunt SC, et al. Genome-wide association identifies OBFC1 as a locus involved in human leukocyte telomere biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(20):9293–9298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911494107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hindorff LALA, MacArthur J, Morales J, et al. A catalog of published genome-wide association studies. [Accessed January 15, 2015]; https://www.genome.gov/gwastudies.

- 27.Chêne G, Thompson SG. Methods for summarizing the risk associations of quantitative variables in epidemiologic studies in a consistent form. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(6):610–621. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgess S, Scott RA, Timpson NJ, Davey Smith G, Thompson SG, EPIC- InterAct Consortium Using published data in Mendelian randomization: a blueprint for efficient identification of causal risk factors. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30(7):543–552. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas DC, Lawlor DA, Thompson JR. Re: Estimation of bias in nongenetic observational studies using “Mendelian triangulation” by Bautista et al. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):511–513. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(2):512–525. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.VanderWeele TJ, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Cornelis M, Kraft P. Methodological challenges in mendelian randomization. Epidemiology. 2014;25(3):427–435. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40(4):304–314. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. [Accessed August 1, 2015]; https://www.seer.cancer.gov/

- 34.Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B. Cancer etiology: variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science. 2015;347(6217):78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1260825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Census Bureau. Welcome to QuickFacts: United States. [Accessed July 11, 2016]; https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/00.

- 36.R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. [Accessed 2015];2013 https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/3.1.2/

- 37.Burgess S, Thompson SG. Bias in causal estimates from Mendelian randomization studies with weak instruments. Stat Med. 2011;30(11):1312–1323. doi: 10.1002/sim.4197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rafnar T, Sulem P, Thorleifsson G, et al. Genome-wide association study yields variants at 20p12.2 that associate with urinary bladder cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(20):5545–5557. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michailidou K, Hall P, Gonzalez-Neira A, et al. Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Collaboration; Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Research Group Netherlands (HEBON); kConFab Investigators; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group; GENICA (Gene Environment Interaction and Breast Cancer in Germany) Network Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):353–361 e1-e2. doi: 10.1038/ng.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang C, Doherty JA, Burgess S, et al. GECCO and GAME-ON Network: CORECT, DRIVE, ELLIPSE, FOCI, and TRICL Genetic determinants of telomere length and risk of common cancers: a Mendelian randomization study. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(18):5356–5366. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]