To the Editors:

Background

Treatment for HIV is lifelong and sustained adherence to treatment is critical to ensure virological suppression (1–3), particularly among children and adolescents who have poorer treatment outcomes than adults with limited information on their adherence (4,5). With low or erratic adherence to treatment, drug levels drop allowing a window of opportunity for virus multiplication and selection of drug-resistant viral strains(6). Therefore, continued careful monitoring of adherence is critical to promptly identify and rectify treatment challenges.

Methods

We conducted a trial of a lay worker delivered treatment support intervention to improve adherence among children aged 6 to 15 years newly diagnosed with HIV infection, in Harare, Zimbabwe. HIV treatment was provided according to national guidelines and treatment adherence was assessed at 48 weeks post ART initiation using the ACTG adherence follow up questionnaire, adapted for this age-group, and administered by research nurses (7). Participants or participants together with their caregivers were asked if they had missed doses over the past three days, over weekends in the past month (as studies have shown some people find it difficult to take their ART medications on weekends), and over the past three months. Separately, for all participants we probed about specific reasons for missing drug doses over the past month. This question was worded, “People may miss their medications for various reasons. Here is a list of possible reasons why this can happen. In the past month have you missed taking your medications because you…” (Figure 1b). The list of reasons was derived from studies that have reported reasons for non-adherence in this age-group (8–10). In addition, participants completed a visual analogue scale (VAS) to self-assess their adherence over the past month. Blood samples for HIV viral-load testing were collected using routine phlebotomy and were analysed using the dual-target COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HIV-1 Test, v2.0 (11). All statistical analysis were carried out using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp). Age was coded into two groups, 6-11 and 12-17.

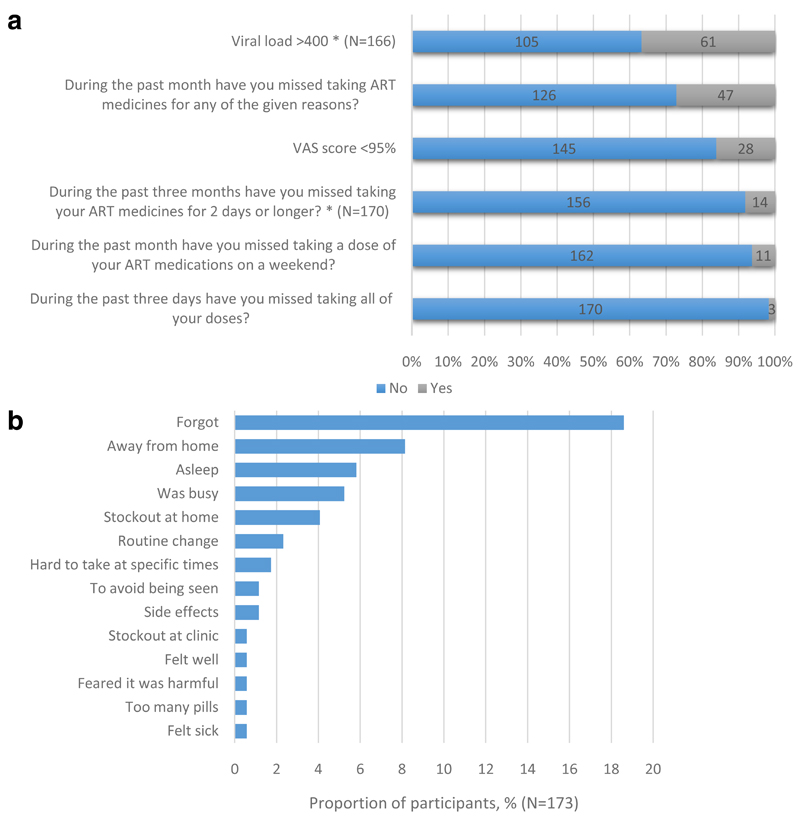

Figure 1.

a: Participant responses to Adherence Questionnaire and Viral Load Results (N=173)

b: Reasons reported for missing doses

Results

At 48 weeks post ART initiation, of the 237 children who initiated ART, adherence data on 173 (73.0%) children (median age 11 (IQR 9-13) years, 55% female) was available. Of the 72 participants in the 6-11 years age group 59 (82%) answered the adherence questions together with a relative. However among the 12-17 years age group 79/101 (78%) participants responded to questions alone. In 3 cases only a relative responded, without the participant. Overall 89 (51.4%) participants responded to the questions alone. Only 3 (1.7%) participants reported missing all their ART doses during the past 3 days, 11 (6.4%) participants reported missing doses on weekends in the past month while 14 (8.2%) reported having stopped taking their ART medicines for 2 days or longer in the past three months (Figure 1a). On the VAS 28 (16.2%) participants reported taking less than 95% of their medication in the previous month and 14 (8.1%) reported taking less than 90%. However, more participants (n=47, 27.2%) reported having missed doses when asked if they had missed doses for any of the given reasons in the past month.

The most common reasons for missing ART doses were directly linked to personal lifestyle: forgetting to take medication (n=32, 18.7%), being away from home (n=14, 8.1%) and falling asleep during dose times (n=10, 5.9%). Only 1 participant reported missing doses for each of the clinical or health system related reasons such as having too many pills to take, feeling sick/ill or clinic stock outs (Figure 1b). Among participants who had a viral load measurement at 48 weeks post ART initiation 61/166 (36.7%) were not virally suppressed. Of the 28 participants who scored <95% on the VAS and had a viral load test result 16 (59%) were unsuppressed, compared to 45/139 (32%) who scored ≥95%. VAS score was strongly associated with viral suppression (OR=0.33, 95%CI 0.14-0.77, p=0.01). There was no association between respondent (participant versus participant plus relative) and reported adherence, type for non-adherence or viral suppression, nor between age and the same outcomes.

Conclusion

In busy clinic settings, adherence is predominantly assessed by asking patients if they have taken doses, which is subject to both desirability and recall bias (12,13). Our findings highlight that the greatest challenges for adherence in this group were directly linked to participants’ daily routines and forgetfulness. We found that probing for possible reasons why participants may have missed doses yielded higher accuracy for identifying non-adherence than asking participants whether they were missing doses. The possible reasons for this may have been that asking specific reasons for missing doses acted as a memory trigger for participants who may have forgotten missing doses or had not considered these instances as poor adherence. We also found that while non-adherence is underreported, when participants do report non-adherence it is a strong indicator of a high HIV viral load.

Although viral load is the gold standard to assess adherence, it is not routinely available in many resource-limited settings (14). Assessing short term adherence and probing to explore the possible reasons why participants miss doses should be used by health care workers in order to obtain more accurate measures for ART adherence.

In our study the responses were given by either caregivers on behalf of the child, jointly by caregivers and children or children alone (for older children). The scales routinely used to measure reported non-adherence have been mainly designed for use among adults, and there are no corresponding scales for children (15). Considerations must be made to validate and adapt self-reported adherence measures for children and to link what health care workers consider as non-adherence to what children and adolescents and their caregivers construe as non-adherence.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: The project was funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

This data has not been presented at any meetings.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Casado JL, Sabido R, Perez-Elías MJ, Antela A, Oliva J, Dronda F, et al. Percentage of adherence correlates with the risk of protease inhibitor (PI) treatment failure in HIV-infected patients. Antivir Ther. 4:157–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cadosch D, Bonhoeffer S, Kouyos R. Assessing the impact of adherence to anti-retroviral therapy on treatment failure and resistance evolution in HIV. [cited 2016 Nov 7];J R Soc Interface. 2012 Sep 7;9(74):2309–20. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0127. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bangsberg DR. J Infect Dis. Supplement 3. Oxford University Press; 2008. May 15, [cited 2016 Oct 12]. Preventing HIV antiretroviral resistance through better monitoring of treatment adherence; pp. S272–8. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim S-H, Gerver SM, Fidler S, Ward H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in adolescents living with HIV. [cited 2016 Oct 12];AIDS. 2014 Aug;28(13):1945–56. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000316. [Internet] Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00002030-201408240-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies M-A, Pinto J. J Int AIDS Soc. Suppl 6. Vol. 18. The International AIDS Society; 2015. [cited 2016 Oct 12]. Targeting 90-90-90--don’t leave children and adolescents behind; p. 20745. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clutter DS, Jordan MR, Bertagnolio S, Shafer RW. HIV-1 drug resistance and resistance testing. Infect Genet Evol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds NR, Sun J, Nagaraja HN, Gifford AL, Wu AW, Chesney Ma. Optimizing measurement of self-reported adherence with the ACTG Adherence Questionnaire: a cross-protocol analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(4):402–9. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318158a44f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biru M, Jerene D, Lundqvist P, Molla M, Abebe W, Hallstr?m I. Caregiver-reported antiretroviral therapy non-adherence during the first week and after a month of treatment initiation among children diagnosed with HIV in Ethiopia. [cited 2017 Jun 15];AIDS Care. 2017 Apr 3;29(4):436–40. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1257098. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ankrah DNA, Koster ES, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Arhinful DK, Agyepong IA, Lartey M. Patient Prefer Adherence. Vol. 10. Dove Press; 2016. [cited 2017 Jun 15]. Facilitators and barriers to antiretroviral therapy adherence among adolescents in Ghana; pp. 329–37. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchanan AL, Montepiedra G, Sirois PA, Kammerer B, Garvie PA, Storm DS, et al. Pediatrics. 5. Vol. 129. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012. May, [cited 2017 Jun 15]. Barriers to medication adherence in HIV-infected children and youth based on self- and caregiver report; pp. e1244–51. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roche Molecular Systems Inc. COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HIV-1 Test, v2.0. Roche Molecular Diagnostics; [cited 2017 Jun 14]. [Internet], Available from: https://molecular.roche.com/assays/cobas-ampliprep-cobas-taqman-hiv-1-test-v2/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassan E. Recall Bias can be a Threat to Retrospective and Prospective Research Designs. Internet J Epidemiol. 2005;3 [Internet], Available from: http://ispub.com/IJE/3/2/13060. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams AB, Amico KR, Bova C, Womack JA. AIDS Behav. 1. Vol. 17. NIH Public Access; 2013. Jan, [cited 2017 Jun 15]. A proposal for quality standards for measuring medication adherence in research; pp. 284–97. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford N, Roberts T, Calmy A. Viral load monitoring in resource-limited settings. [cited 2016 Nov 7];AIDS. 2012 Aug;26(13):1719–20. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283543e2c. [Internet], Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00002030-201208240-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies M-A, Boulle A, Fakir T, Nuttall J, Eley B. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in young children in Cape Town, South Africa, measured by medication return and caregiver self-report: a prospective cohort study. [cited 2017 Jun 15];BMC Pediatr. 2008 8(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-8-34. [Internet], Available from: http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/231/art%253A10.1186%252F1471-2431-8-34.pdf?originUrl=http%3A%2F%2Fbmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com%2Farticle%2F10.1186%2F1471-2431-8-34&token2=exp=1497541861~acl=%2Fstatic%2Fpdf%2F231%2Fart%25253A10.1186%25252F1471-2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]