Abstract

Objective

Airway inflammatory patterns in older asthmatics are poorly understood despite high asthma-related morbidity and mortality. In this study, we sought to define the relationship between exposure to traffic pollutants, biomarkers in induced sputum, and asthma control in older adults.

Methods

Induced sputum was collected from 35 non-smoking adults ≥65 years with a physician’s diagnosis of asthma and reversibility with a bronchodilator or a positive methacholine challenge. Patients completed the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ), and Elemental Carbon Attributable to Traffic (ECAT), a surrogate for chronic diesel particulate exposure, was determined. Equal numbers of subjects with high (≥0.39 µg/m3) versus low (<0.39 µg/m3) ECAT were included. Differential cell counts were performed on induced sputum, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) and eosinophil peroxidase (EPO) were measured in supernatants. Regression analyses were used to evaluate the relationship between sputum findings, ACQ scores, and ECAT.

Results

After adjustment for potential confounders, subjects with poorly controlled asthma based on ACQ ≥ 1.5 (n = 7) had significantly higher sputum eosinophils (median = 4.4%) than those with ACQ < 1.5 (n = 28; eosinophils = 2.6%; β = 10.1 [95% CI = 0.1–21.0]; p = 0.05). Subjects with ACQ ≥ 1.5 also had significantly higher sputum neutrophils (84.2% versus 65.2%; β = 7.1 [0.2–14.6]; p = 0.05). Poorly controlled asthma was associated with higher sputum EPO (β = 2.4 [0.2–4.5], p = 0.04), but not MPO (p = 0.9). High ECAT was associated with higher eosinophils (β = 10.1 [1.8–18.4], p = 0.02) but not higher neutrophils (p = 0.6).

Conclusions

Poorly controlled asthma in older adults is associated with eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation. Chronic residential traffic pollution exposure may be associated with eosinophilic, but not neutrophilic inflammation in older asthmatics.

Keywords: Air pollution, asthma, airway inflammation, eosinophilic, induced sputum, neutrophilic, older adults

Introduction

The burden of disease in asthmatics ages 65 years and older is substantial and underappreciated. While mortality from asthma overall is less than 2.2/100 000, asthma-related mortality among older adults is almost 5 times greater, with 10.5/100 000 seniors dying from asthma [1,2]. Older asthmatics are three times more likely to be classified as having severe disease, and to experience an asthma exacerbation requiring systemic corticosteroids [3]. Asthma-related quality of life is lower among older asthmatics, and asthma-related health care costs are twice those of younger asthmatics [3,4].

Previous studies suggest that the airway inflammatory phenotype of older asthmatics may differ from younger patients [5,6]. The relationship between asthma endophenotypes, or phenotypes that incorporate biological markers, and severity has not been defined in older adults. It is theorized that a more neutrophilic phenotype may explain increased severity in this population [5]. It is well known that neutrophils increase with aging in normal lungs, but the clinical significance of airway neutrophilia in older asthmatics is not clear [5,6]. In a well-controlled cross-over study, McCreanor et al. reported that real-world traffic particulate exposure acutely reduced lung function and increased sputum neutrophils and myeloperoxidase (MPO) in adult asthmatics [7]. Defining the relationship between traffic pollutants, airway inflammation, and asthma control in older asthmatics is of particular interest, given that asthmatics ages 65 and older are disproportionately impacted by traffic related air pollution [8–13]. Although we recently found that high exposure to residential traffic pollution is the strongest predictor of poor asthma control in older adults, airway inflammatory patterns in traffic-pollutant exposed older asthmatics have not been previously examined [8]. In addition, while sputum MPO and eosinophil peroxidase (EPO) are associated with neutrophilic and eosinophilic inflammation, respectively, in younger asthmatics and in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), these biomarkers have not been systematically evaluated in older asthmatics [14]. For the first time, we evaluated the relationship between sputum biomarkers, including cell counts, MPO, EPO, residential traffic pollution exposure, and asthma control in older adults. We hypothesized that neutrophilic airway inflammation would be associated with chronic, residential traffic pollution exposure and poor asthma control in older adults.

Methods

Study population: clinical and exposure data

Subjects were recruited from the Cincinnati Asthma Severity in Older Adults Cohort, which has been previously described [8]. The overall cohort includes 175 asthmatics ages 65 years and older (mean age 74 years) recruited from the Greater Cincinnati metropolitan area from 2010 to 2012. All subjects had a physician’s diagnosis of asthma based on ICD-9 codes, and objective confirmation of asthma by spirometry (12% and 200 ml change in forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] with bronchodilator) or methacholine challenge testing (PC20 < 4 mg/ml) [8]. Potential subjects with a physician’s diagnosis of COPD or New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class 3 or greater congestive heart failure (CHF), defined as marked activity limitation with physical activity due to CHF, were excluded [15]. The cohort was recruited from Allergy and Pulmonary subspecialty clinics in order to increase our ability to identify risk factors for more severe asthma. Recruited subjects were representative of the Greater Cincinnati metropolitan area in terms of demographics and geographic locations [8].

In order to evaluate the impact of chronic traffic pollution exposure on sputum findings, equal numbers of subjects with high versus low residential exposure to elemental carbon attributable to traffic (ECAT) were recruited for the sputum sub-study (Table 1). Average daily residential exposure to ECAT, a surrogate for diesel particulate exposure, was estimated from a previously described land-use regression model that accounts for truck traffic, elevation, and distance to major roads (r2 = 0.73) [8,16]. Based on a linear spline model, high ECAT was defined as ≥0.39 µg/m3, which was also the upper quartile of ECAT exposure [8]. Because we were also interested in the relationship between asthma control and sputum findings, we recruited approximately equal numbers of subjects with Asthma Control Questionnaire-6 (ACQ) scores ≥1.5 versus <1.5. The ACQ is a validated survey that evaluates asthma symptoms and albuterol use for the previous week; an ACQ ≥ 1.5 is considered a validated cut-point for not well controlled asthma in the previous week [17,18]. In previous validation studies, an ACQ < 0.75 was indicative of well controlled asthma, while an ACQ between 0.75 and 1.5 was indeterminate [17,18]. Because of the design and sample size for this study, subjects with an ACQ < 0.75 were treated the same as those with an ACQ between 0.75 and 1.5. Target enrollment was 35 subjects, based on a power calculation for the number of subjects needed to evaluate the relationship between ACQ scores and sputum findings. Forty subjects (eight with high ECAT and high ACQ scores; eight with high ECAT and low ACQ scores, eight with low ECAT and high ACQ scores, and eight with low ECAT and low ACQ scores) were initially recruited for sputum induction, because of the potential that some subjects would not be able to provide adequate samples. Subjects with high versus low ECAT and high versus low ACQ scores were randomly recruited from the cohort with respect to other potential covariates. Subjects who used tobacco products within 2 years were excluded from sputum induction, given that current tobacco use can influence sputum biomarkers [19].

Table 1.

Demographic and health characteristics, exposures, and medication use for 35 asthmatics ages 65 years and older.

| Characteristic or exposure | N (% of 35) |

|---|---|

| Females | 19 (54%) |

| Males | 16 (46%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 26 (74%) |

| African-American | 8 (23%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (3%) |

| Nasal polyps | 9 (26%) |

| No nasal polyps | 26 (74%) |

| Age of asthma symptoma onset | |

| 0–40 | 14 (40%) |

| ≥41 years | 21 (60%) |

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | |

| <30 | 18 (52%) |

| ≥30 | 17 (48%) |

| Atopic (SPT+)b | 22 (63%) |

| Non-atopic | 13 (37%) |

| Ever smoked cigarettes, cigars, or a pipe | 17 (49%) |

| <10 pack years | 7 |

| 10–20 pack years | 5 |

| >20 pack years | 5 |

| Never smoked | 18 (51%) |

| Elemental carbon attributable to traffic (ECAT), µg/m3c | |

| High (0.39–0.81) | 16 (46%) |

| Low (0.23–0.38) | 19 (54%) |

| Medications | |

| SABAd, low dose ICSe, or leukotriene antagonist alone | 2 (6%) |

| Low or medium dose ICS ± LABAf | 12 (34%) |

| High dose ICS ± LABA, ± daily oral corticosteroids | 21 (60%) |

Wheezing, shortness of breath, or chronic cough not explained by another problem.

At least one positive skin prick test to a panel of 10 aeroallergens (cat, dog, timothy grass, white oak, maple mix, short ragweed, dust mite mix [50% Dermatophagoides farinae and 50% Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus], Alternaria tenuis, Aspergillus fumigatus, and German cockroach).

ECAT, which is a surrogate for diesel particulate exposure, was determined from an existing land-use regression model. High versus low elemental carbon attributable to traffic (ECAT) exposure was based on a linear spline model.

SABA = Short-acting β2-agonist.

ICS = Inhaled corticosteroid.

LABA = Long-acting β2-agonist.

Out of the 40 recruited subjects, two were not induced because of a post-bronchodilator FEV1 < 50%, and three had inadequate sputum samples. Subjects who completed sputum induction (n = 35; Table 1) were similar to the overall cohort in terms of gender, race, body mass index (BMI), atopy (based on one or more positive skin prick tests to a panel of 10 aeroallergens), asthma symptom onset after age 40 years, nasal polyposis, and former smoking [8]. Medication use in the previous month for subjects undergoing sputum induction was also similar to that for the overall cohort (Supplemental Table 2) [8]. Subjects repeated the ACQ and spirometry on the day of induction [18]. Induced subjects had similar mean ACQ scores (0.8 ± 0.7) and mean pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (72 ± 17%) to the overall cohort, on the day of induction [8]. Subjects signed an informed consent approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board.

Sputum induction and analysis

Recruited subjects with a post-bronchodilator FEV1 > 50% inhaled nebulized saline, resulting in expectoration. After the administration of albuterol, increasing concentrations of saline (3%, 4%, and 5% for 5 min each) were administered using an ultrasonic nebulizer (Omron Model NE-U12). Spirometry was performed using an nSpire Koko spirometer prior to induction and after each dose of saline; administration of saline was stopped and albuterol was re-administered if FEV1 fell by 10% or more from baseline. Sputum was processed using standard methods with D-PBS and dithiothreitol [20]. The inflammatory cell differentials for 300 cells per slide (stained with Diff Quick, Volu-Sol Inc, Salt Lake City, UT) were determined by three readers blinded to clinical data; at least 80% agreement was required [5]. MPO was measured in supernatant (without dithiothreitol) using a commercial ELISA assay (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) [21]. An experiment involving the EPO inhibitor, resorcinol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) verified that the MPO assay was not impacted by EPO. EPO was measured in supernatants (without dithiothreitol) with a quantitative colorimetric assay using o-phenylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as a substrate because it does not show significant cross-reactivity with MPO [22]. This EPO assay was modified from murine studies because it is simple, inexpensive, and does not require radioactivity [22]. Human EPO (LeeBioSolutions, St.Louis, MO) was used as a standard. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm after 15 min. MPO and EPO levels were corrected for supernatant protein levels (Coomassie Plus, Bradford, Rockford, IL).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and regression analyses were performed in SAS 9.3 to evaluate the relationship between biomarker levels and ACQ ≥ 1.5 (poorly controlled asthma), and ECAT [18]. Logistic regression was used for dichotomous outcomes, and mixed linear regression was used for continuous outcomes. Cell counts and differentials, EPO, and MPO levels were log-transformed to approximate normality. Odds ratios represent the odds of having high versus low ECAT given various subject characteristics. In order to allow for comparability with data from other studies (5, 23, 24), median values for biomarkers, including cell counts and differentials, are presented in Tables and Figures, although log-transformed, continuous data were used for regression analyses. In order to minimize the impact of potential confounders, results were also adjusted in the regression model for gender, nasal polyps, and the age of asthma onset, because these covariates were significantly associated with sputum cell counts and differentials based on a backward elimination with alpha = 0.15.

Results

Induced sputum findings based on clinical characteristics

Demographic information, health characteristics, medication use and exposures for induced subjects are listed in Table 1. The median (interquartile range = IQR) cell differential from induced sputum of the 35 enrolled subjects was: eosinophils 2.7 (12.5)%; neutrophils 66.5 (32.5)%; macrophages 17.7 (22.7)%; and lymphocytes 0.9 (1.4)%. Sputum findings based on host characteristics, medication use, and exposures, with the exception of ECAT and ACQ, are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Female gender and nasal polyps were significantly associated with higher sputum eosinophils (median eosinophils [IQR] = 4.3 [20.3]% versus 2.2 [2.9]% for females versus males, β = 11.0 [95% CI = 2.1–19.8], p = 0.02; and 3.4 [36.7]% versus 2.4 [9.1]%, β = 13.1 [3.2–22.9], p = 0.01 for subjects with nasal polyps versus those without nasal polyps). Nasal polyps were also significantly associated with lower sputum neutrophils (53.0 [22.0]% versus 73.3 [20.7]%; β = −18.9 [−31.9 to −5.9]), p = 0.006). The onset of asthma symptoms after age 40 years was significantly associated with higher sputum neutrophils (76.6 [20.7]% versus 62.3 [17.0]%; β = 14.5 [2.4–26.6]), p = 0.02). There were no significant relationships between sputum findings and other host characteristics presented in Table 1, including atopy or smoking. There was no significant association between medication use at the time of induction and sputum eosinophil or neutrophil counts (Supplemental Table 1).

Elemental carbon attributable to traffic (ECAT) exposure versus other subject characteristics

Table 2 displays the relationship between ECAT exposure and other subject characteristics, exposures, and ACQ scores. In the 35 induced subjects, there were no statistically significant relationships between ECAT and other subject characteristics (not including sputum findings), exposures, or ACQ scores.

Table 2.

Demographic information, health characteristics, and Asthma Control Questionnaire-6 (ACQ) scores based on Elemental Carbon Attributable to Traffic (ECAT)a exposure for 35 asthmatics ages 65 years and older.

| No. (%) of 16 subjects with High ECAT (0.39–0.81 µg/m3) |

No. (%) of 19 subjects with Low ECAT (0.23–0.38 µg/m3) |

Odds ratio [95% CI]b |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 10 (63%) | 9 (47%) | 0.4 [0.08–2.4] | 0.4 |

| Males | 6 (37%) | 10 (53%) | ||

| Race | 1.3 [0.3–6.7] | 0.3 | ||

| Caucasian | 10 (63%) | 16 (84%) | ||

| African-American | 5 (31%) | 3 (16%) | ||

| Hispanic | 1 (6%) | 0 | ||

| Nasal polyps | 3 (19%) | 6 (32%) | 0.6 [0.1–3.6] | 0.4 |

| No nasal polyps | 13 (81%) | 13 (68%) | ||

| Age of asthma symptomc onset | 0.9 [0.2–4.7] | 0.3 | ||

| 0–40 | 10 (62%) | 8 (42%) | ||

| ≥41 years | 6 (38%) | 11 (58%) | ||

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | 0.8 [0.2–3.8] | 0.4 | ||

| <30 | 8 (50%) | 10 (53%) | ||

| ≥30 | 8 (50%) | 9 (47%) | ||

| Atopic (SPT+)d | 11 (69%) | 11 (58%) | 2.1 [0.4–11.3] | 0.8 |

| Non-atopic | 5 (31%) | 8 (42%) | ||

| Ever smoked cigarettes, cigars, or a pipe | 9 (56%) | 8 (42%) | 1.5 [0.3–7.7] | 0.1 |

| Never smoked | 7 (44%) | 11 (58%) | ||

| ACQ ≥ 1.5 (uncontrolled asthma)e | 3 (19%) | 4 (21%) | 1.0 [0.2–6.7] | 0.8 |

| ACQ < 1.5 | 13 (81%) | 15 (79%) |

Elemental carbon attributable to traffic (ECAT), which is a surrogate for diesel particulate exposure, was determined from an existing land-use regression model. High versus low ECAT exposure was based on a linear spline model.

Represents the odds of having high versus low ECAT given various subject characteristics listed in the first column (e.g. the odds of having high versus low ECAT in females versus males).

Wheezing, shortness of breath, or chronic cough not explained by another problem.

At least one positive skin prick test to a panel of 10 aeroallergens (cat, dog, timothy grass, white oak, maple mix, short ragweed, dust mite mix [50% Dermatophagoides farinae and 50% Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus], Alternaria tenuis, Aspergillus fumigatus, and German cockroach).

An ACQ score ≥ 1.5 is a validated measure of uncontrolled asthma for the previous week.

A p value of <0.05 is significant.

Induced sputum findings based on ACQ scores

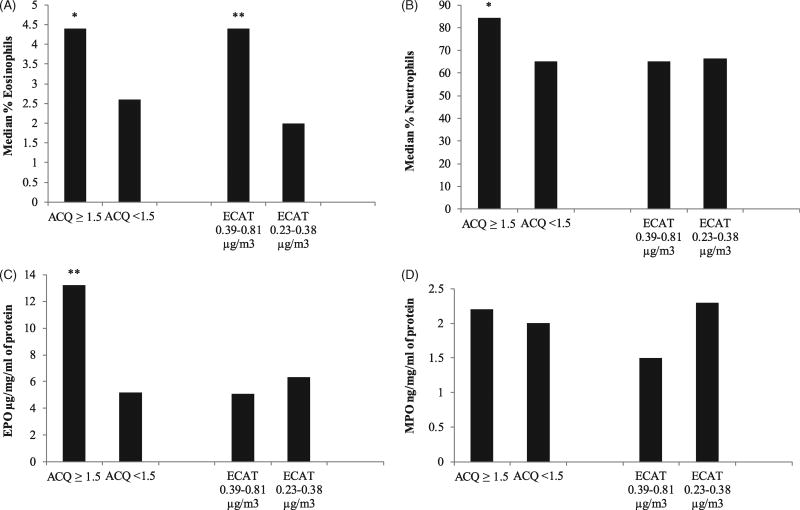

As seen in Figure 1A and Table 3, subjects with uncontrolled asthma (ACQ ≥ 1.5) had significantly higher sputum eosinophils (median [IQR] = 4.4 [37.4] % for ACQ ≥ 1.5 versus 2.6 [6.5] % for ACQ < 1.5; β = 10.1 [95% CI = 0.1–21.0]; p = 0.05, after adjustment for gender, nasal polyps, and age of asthma onset). Subjects with uncontrolled asthma also had significantly higher sputum neutrophils (84.2 [38.4] % for ACQ ≥ 1.5 versus 65.2 [28.2]% for ACQ < 1.5; adjusted β = 7.1 [0.2–14.6]; p = 0.05; Figure 1B). Poorly controlled asthma was significantly associated with higher sputum EPO (13.2 [14.0] µg/mg/ml of protein for ACQ ≥ 1.5 versus 5.2 [6.1] µg/mg/ml of protein for ACQ < 1.5; adjusted β = 2.4 [0.2–4.5]; p = 0.04; Figure 1C). MPO was not significantly associated with ACQ scores (β = 0.02 [−0.4 to 0.4]; p = 0.2; Figure 1D). The correlation between sputum neutrophil counts and MPO was similar to reported values (r2 = 0.4; p = 0.07) [7]. The correlation between sputum eosinophil counts and EPO was 0.29, p = 0.08.

Figure 1.

Sputum biomarkers versus asthma control questionnaire (ACQ) scores and elemental carbon attributable to traffic (ECAT) for 35 asthmatics ages 65 years and older. A: Median percent eosinophils. *p = 0.05 (β = 10.1 [0.1–21.0]) for the difference in percent sputum eosinophils between subjects with an ACQ ≥ 1.5 (uncontrolled asthma) versus those with an ACQ < 1.5. **p < 0.05 (β = 10.1 [1.8–18.4]) for the difference in percent sputum eosinophils between subjects with ECAT of 0.39–0.81 µg/m3 (high exposure to traffic related air pollution) versus those with ECAT of 0.23–0.38 µg/m3 (low exposure). B: Median percent neutrophils.*p = 0.05 (β = 7.1 [0.2–14.6]) for the difference in percent sputum neutrophils between subjects with an ACQ ≥ 1.5 (uncontrolled asthma) versus those with an ACQ < 1.5. C: Median eosinophil peroxidase (EPO) levels. **p < 0.05 (β = 2.4 [0.2–4.5]) for the difference in EPO levels between subjects with an ACQ ≥ 1.5 (uncontrolled asthma) versus those with an ACQ < 1.5. D: Median myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels.

Table 3.

Median and interquartile range for sputum biomarkers versus Asthma Control Questionnaire-6 (ACQ)a scores for 35 Asthmatics ages 65 years and older.

| Biomarkerb | ACQ ≥ 1.5 (Uncontrolled); n = 7 | ACQ < 1.5 (Controlled); n = 28 | β-coefficient [95% CI]c | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Eosinophils | 4.4 (37.4) | 2.6 (6.5) | 10.1 [0.1 to 21.0] | 0.05 |

| No. Eosinophils/300 cells | 13.0 (111.0) | 7.5 (19.5) | 25.2 [−5.7 to 56.2] | 0.09 |

| % Neutrophils | 84.2 (38.4) | 65.2 (28.2) | 7.1 [0.2–14.6] | 0.05 |

| No. Neutrophils/300 cells | 250.0 (118.0) | 188.5 (84.5) | 0.3 [0.1–0.6] | 0.008 |

| EPO µg/mg/ml of proteind | 13.2 (14.0) | 5.2 (6.1) | 2.4 [0.2–4.5] | 0.04 |

| MPO ng/mg/ml of proteind | 2.2 (2.2) | 2.0 (3.5) | 0.02 [−0.4–0.4] | 0.9 |

Higher ACQ scores indicate poorer control; an ACQ ≥ 1.5 is associated with uncontrolled asthma.

The median and interquartile range (IQR) are presented for relevant biomarkers.

Regression analyses of percent cell differentials and log-transformed cell counts, EPO and MPO levels and ACQ ≥ 1.5 versus ACQ < 1.5 were performed. Results were adjusted for gender, nasal polyps, the age of asthma onset, and ECAT levels (covariates were included based on a backward elimination with alpha = 0.15).

EPO (Eosinophil peroxidase) and MPO (Myeloperoxidase) from sputum supernatant were adjusted for protein levels.

A p value of <0.05 is significant.

Induced sputum findings based on ECAT exposure

As seen in Figure 1A and Table 4, higher sputum eosinophils, were significantly associated with ECAT ≥ 0.39 µg/m3 (4.4 [20.8] % for high ECAT versus 2.0 [3.5] % for low ECAT; adjusted β = 10.1 [1.8–18.4]; p = 0.02). Higher sputum neutrophils were not associated with ECAT exposure, however (adjusted β = −3.3 [−14.7 to 8.0]; p = 0.6; Figure 1B). There were no significant associations between EPO and ECAT (adjusted β = −0.2 [−0.6 to 0.2]; p = 0.6; Figure 1C), or between MPO and ECAT (adjusted β = −0.2 [−0.8 to 0.3]; p = 0.4; Figure 1D).

Table 4.

Median and interquartile range (IQR) for sputum biomarkers versus elemental carbon attributable to traffic (ECAT)a in 35 asthmatics ages 65 years and older.

| Biomarkerb | High ECAT (0.39–0.81 µg/m3) | Low ECAT (0.23–0.38 µg/m3) | β-coefficient [95% CI]c | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Eosinophils | 4.4 (20.8) | 2.0 (3.5) | 10.1 [1.8–18.4] | 0.02 |

| No. Eosinophils/300 cells | 13.0 (61.0) | 6.0 (10.0) | 1.1 [0.2–2.0] | 0.02 |

| % Neutrophils | 65.2 (28.7) | 66.3 (36.7) | −3.3 [−14.7 to −8.0] | 0.6 |

| No. Neutrophils/300 cells | 193.0 (89.0) | 193.0 (109.0) | −0.02 [−0.3 to −0.2] | 0.8 |

| EPO µg/mg/ml of proteind | 5.1 (7.2) | 6.3 (9.4) | −0.2 [−0.6 to −0.2] | 0.6 |

| MPO ng/mg/ml of proteind | 1.5 (2.1) | 2.3 (4.0) | −0.2 [−0.8 to −0.3] | 0.4 |

ECAT, which is a surrogate for diesel particulate exposure, was determined from an existing land-use regression model. High versus low elemental carbon attributable to traffic (ECAT) exposure was based on a linear spline model.

The median and interquartile range (IQR) are presented for sputum biomarkers.

Regression analyses of percent cell differentials, and log-transformed cell counts, EPO and MPO and high versus low ECAT. Results were adjusted for gender, nasal polyps, and the age of asthma onset (covariates were included based on a backward elimination with alpha = 0.15).

EPO (Eosinophil peroxidase) and MPO (Myeloperoxidase) from sputum supernatant were adjusted for protein levels.

A p value of <0.05 is significant.

Discussion

Despite high morbidity and mortality from asthma, few studies have examined airway inflammatory patterns in asthmatics ages 65 years and older [2,5,25]. Moreover, no studies have previously examined the relationship between traffic pollution and airway inflammation in this population, despite their increased susceptibility to air pollutants [8,10,12,13]. The hypothesis that neutrophilic airway inflammation would be associated with both air pollution exposure and poorly controlled asthma in older adults was not confirmed. Nevertheless, this study defined sputum biomarkers that may be applied to future mechanistic and epidemiologic investigations of poorly controlled asthma and susceptibility to air pollutants in older adults.

Previous studies have described the presence of elevated sputum neutrophils in older asthmatics, but did not investigate the relationship between elevated sputum neutrophils and clinical outcomes measures in this population [5,25]. Our results demonstrate for the first time that sputum neutrophilia is associated with poorly controlled asthma, based on the validated ACQ, in asthmatics ages 65 years and older. In addition, the novel finding that sputum neutrophilia is associated with late onset asthma (>40 years) has potential mechanistic implications for late-onset asthma phenotypes [23,26,27].

Of note, sputum eosinophilia was also associated with poorly controlled asthma in older asthmatics. This finding is consistent with studies indicating that eosinophil numbers do not decrease with age in asthmatics [24]. In addition, females and patients with nasal polyps maintain sputum eosinophilia into older age [28,29]. We did not identify any statistically significant relationships between previous smoking and sputum findings, although current smokers were excluded from the study. Sputum findings were also not significantly different between atopic and non-atopic subjects in this population. Some studies in younger populations previously found an association between atopy and higher sputum eosinophils, while others did not [30,31]. We speculate that the lack of an association between atopy and sputum eosinophils in older asthmatics may in part be due to the prominence of other inflammatory pathways, particularly those related to nasal polyps. In addition, the ability of our study to assess secondary findings, such as the impact of smoking or atopy on sputum cytology, may be limited by the small sample size of this study.

To our knowledge, previous human studies regarding the relationship between eosinophil peroxidase (EPO) in sputum supernatant and asthma outcomes in older adults have not been conducted. In this study, EPO was found to be elevated in the sputum of poorly controlled older asthmatics. Further validation of this novel biomarker of eosinophilic inflammation in human studies is warranted, especially given that it may be more economical and efficient than existing alternatives.

Although this study was not designed to evaluate the relationship between ECAT and ACQ scores, higher ECAT was significantly associated with poorer ACQ scores in a previous study involving 104 older asthmatics from this cohort [8]. Surprisingly, chronic residential traffic pollution exposure, estimated by ECAT, was associated with eosinophilic, but not neutrophilic inflammation in older asthmatics [8]. Of note, an increase in eosinophils has previously been reported in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of mice exposed to phenanthraquinone, a diesel exhaust constituent [32]. Diesel exhaust exposure generated under urban running conditions (as opposed to idling conditions commonly evaluated in exposure chamber studies) has also recently been associated with BAL-eosinophilia in healthy human subjects [33]. The increase in airway eosinophils occurring with diesel exhaust exposure is thought to be mediated via oxidative stress through NFκβ and IL-13-eotaxin pathways that are independent of STAT-6 [34]. It is unclear why our study did not find a relationship between ECAT exposure and sputum neutrophils in older adults, given that acute diesel exhaust exposure has previously been associated with sputum neutrophilia in adult asthmatics [7]. It is possible that this finding may be related to the differential quantitative effects of acute versus long-term exposure, or that exposure to different constituents of diesel exhaust (i.e. those generated during idling versus moving traffic situations) may lead to variable inflammatory responses [33]. It is also possible that traffic pollution exposure may result in differential immune responses based on age-related differences in the inflammatory milieu [5,24,25]. Further evaluation of these relationships with a larger sample size, repeated sputum sampling over time, and additional biomarkers of eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation may provide much needed insights regarding these issues.

In summary, neutrophilic airway inflammation may be associated with late-onset adult asthma and with poor asthma control in older asthmatics, but the association between sputum eosinophilia and poor asthma control also persists into older adulthood. In addition, our findings support the involvement of eosinophilic, but not neutrophilic airway inflammation in older adult asthmatics chronically exposed to traffic pollutants. The relationship between eosinophilic inflammation, traffic pollution exposure and asthma morbidity in older adults will be further investigated in future studies.

Conclusions

Poorly controlled asthma in older adults is associated with eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation. Residential traffic pollution exposure may be associated with eosinophilic, but not neutrophilic inflammation in older adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank participants from the Cincinnati Asthma Severity in Older Adults Study who provided sputum samples. We thank the research team at the Bernstein Clinical Research Center who assisted with sputum collection. We also thank Linda Levin, PhD, from the UC Department of Environmental Health for assistance with the statistical analysis, and Jennifer Kannan, MD from the UC Department of Medicine for assistance with laboratory procedures.

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article. This study was supported by NIH/NCRR 8 KL2 TR000078-05; NIEHS P30-ES006096; USPHS UL1 RR026314; Grant 8 UL1 TR000077; and NIEHS ES11170. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Moorman JE, Rudd RA, Johnson CA, King M, Minor P, Bailey C, Scalia MR, Akinbami LJ. National surveillance for asthma–United States, 1980–2004. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2007;56:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai CL, Lee WY, Hanania NA, Camargo CA., Jr Age-related differences in clinical outcomes for acute asthma in the United States, 2006–2008. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1252–1258. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plaza V, Serra-Batlles J, Ferrer M, Morejon E. Quality of life and economic features in elderly asthmatics. Respiration. 2000;67:65–70. doi: 10.1159/000029465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stupka E, deShazo R. Asthma in seniors: Part 1. Evidence for underdiagnosis, undertreatment, and increasing morbidity and mortality. Am J Med. 2009;122:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyenhuis SM, Schwantes EA, Evans MD, Mathur SK. Airway neutrophil inflammatory phenotype in older subjects with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1163–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer KC, Rosenthal NS, Soergel P, Peterson K. Neutrophils and low-grade inflammation in the seemingly normal aging human lung. Mechan Age Dev. 1998;104:169–181. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCreanor J, Cullinan P, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Stewart-Evans J, Malliarou E, Jarup L, Harrington R, et al. Respiratory effects of exposure to diesel traffic in persons with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2348–2358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein TG, Ryan PH, LeMasters GK, Bernstein CK, Levin LS, Bernstein JA, Villareal MS, Bernstein DI. Poor asthma control and exposure to traffic pollutants and obesity in older adults. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108:423–428. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexeeff SE, Litonjua AA, Suh H, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Schwartz J. Ozone exposure and lung function: effect modified by obesity and airways hyperresponsiveness in the VA normative aging study. Chest. 2007;132:1890–1897. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson HR, Atkinson RW, Bremner SA, Marston L. Particulate air pollution and hospital admissions for cardiorespiratory diseases: are the elderly at greater risk? Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;40:39s–46s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00402203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko FW, Tam W, Wong TW, Lai CK, Wong GW, Leung TF, Ng SS, Hui DS. Effects of air pollution on asthma hospitalization rates in different age groups in Hong Kong. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1312–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng YY, Wilhelm M, Rull RP, English P, Ritz B. Traffic and outdoor air pollution levels near residences and poorly controlled asthma in adults. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98:455–463. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60760-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen ZJ, Bonnelykke K, Hvidberg M, Jensen SS, Ketzel M, Loft S, Sorensen M, et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and asthma hospitalisations in older adults: a cohort study. Thorax. 2012;67:6–11. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keatings VM, Barnes PJ. Granulocyte activation markers in induced sputum: comparison between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and normal subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:449–453. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association. Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis and Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels. 9. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan PH, Bernstein DI, Lockey J, Reponen T, Levin L, Grinshpun S, Villareal M, et al. Exposure to traffic-related particles and endotoxin during infancy is associated with wheezing at age 3 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:1068–1075. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1307OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juniper EF, O’Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:902–907. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d29.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juniper EF, Bousquet J, Abetz L, Bateman ED. Identifying ‘well-controlled’ and ‘not well-controlled’ asthma using the Asthma Control Questionnaire. Respir Med. 2006;100:616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomson NC, Chaudhuri R, Heaney LG, Bucknall C, Niven RM, Brightling CE, Menzies-Gow AN, et al. Clinical outcomes and inflammatory biomarkers in current smokers and exsmokers with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1008–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pizzichini E, Pizzichini MM, Efthimiadis A, Evans S, Morris MM, Squillace D, Gleich JG, et al. Indices of airway inflammation in induced sputum: reproducibility and validity of cell and fluid-phase measurements. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:308–317. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nightingale JA, Rogers DF, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. No effect of inhaled budesonide on the response to inhaled ozone in normal subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:479–486. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9905031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider T, Issekutz AC. Quantitation of eosinophil and neutrophil infiltration into rat lung by specific assays for eosinophil peroxidase and myeloperoxidase. Application in a Brown Norway rat model of allergic pulmonary inflammation. J Immunol Meth. 1996;198:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jatakanon A, Uasuf C, Maziak W, Lim S, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Neutrophilic inflammation in severe persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1532–1539. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9806170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathur SK, Schwantes EA, Jarjour NN, Busse WW. Age-related changes in eosinophil function in human subjects. Chest. 2008;133:412–419. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks CR, Gibson PG, Douwes J, Van Dalen CJ, Simpson JL. Relationship between airway neutrophilia and aging in asthmatics and non-asthmatics. Respirology. 2013;18:857–865. doi: 10.1111/resp.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, Berry MA, Thomas M, Brightling CE, Wardlaw AJ, Green RH. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:218–224. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, D’Agostino R, Jr, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:315–323. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castro M, Mathur S, Hargreave F, Boulet LP, Xie F, Young J, Wilkins HJ, et al. Reslizumab for poorly controlled, eosinophilic asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1125–1132. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0396OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belda J, Leigh R, Parameswaran K, O’Byrne PM, Sears MR, Hargreave FE. Induced sputum cell counts in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:475–478. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9903097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Carvalho-Pinto RM, Cukier A, Angelini L, Antonangelo L, Mauad T, Dolhnikoff M, Rabe KF, Stelmach R. Clinical characteristics and possible phenotypes of an adult severe asthma population. Respir Med. 2012;106:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schleich FN, Seidel L, Sele J, Manise M, Quaedvlieg V, Michils A, Louis R. Exhaled nitric oxide thresholds associated with a sputum eosinophil count ≥3% in a cohort of unselected patients with asthma. Thorax. 2010;65:1039–1044. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.124925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiyoshi K, Takano H, Inoue KI, Ichinose T, Yanagisawa R, Tomura S, Kumagai Y. Effects of phenanthraquinone on allergic airway inflammation in mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1243–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sehlstedt M, Behndig AF, Boman C, Blomberg A, Sandstrom T, Pourazar J. Airway inflammatory response to diesel exhaust generated at urban cycle running conditions. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:1144–1150. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.529181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takizawa H, Abe S, Okazaki H, Kohyama T, Sugawara I, Saito Y, Ohtoshi T, et al. Diesel exhaust particles upregulate eotaxin gene expression in human bronchial epithelial cells via nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L1055–L1062. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00358.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.