Abstract

Purpose of review

For the more than 636,000 adults with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the U.S., kidney transplantation is the preferred treatment compared to dialysis. Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) comprised 31% of kidney transplantations in 2015, an 8% decrease since 2004. We aimed to summarize the current literature on decision aids that could be used to improve LDKT rates.

Recent findings

Decision aids are evidence-based tools designed to help patients and their families make difficult treatment decisions. LDKT decision aids can help ESRD patients, patients’ family and friends, and healthcare providers engage in treatment decisions and thereby overcome multifactorial LDKT barriers.

Summary

We identified 12 LDKT decision aids designed to provide information about LDKT, and/or to help ESRD patients identify potential living donors, and/or to help healthcare providers make decisions about treatment for ESRD or living donation. Of these, 4 were shown to be effective in increasing LDKT, donor inquiries, LDKT knowledge, and willingness to discuss LDKT. Although each LDKT decision aid has limitations, adherence to decision aid development guidelines may improve decision aid utilization and access to LDKT.

Keywords: kidney transplantation, living donor, living donor kidney transplantation, dialysis, end stage renal disease

Introduction

Kidney transplantation is the preferred treatment for most patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) compared to dialysis [1, 2]. With more than 636,000 adults diagnosed with ESRD [3], the gap between the demand for kidneys and available organs continues to widen. Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) can help reduce the organ shortage. Recipients of LDKT have improved survival [1, 2, 4] and enhanced quality of life [1] compared to recipients of deceased donor kidney transplantation. However, LDKT comprised only 31% of kidney transplantations in 2013, an 8% decrease since 2004 [5, 6], suggesting substantial barriers to pursuing LDKT.

While decisions about pursuing LDKT can be difficult to make [7, 8], tools that assist potential recipients, potential donors, and/or their healthcare providers in making decisions may reduce uncertainty and possibly increase LDKT rates. Decision aids can help engage and inform patients of their treatment options by presenting evidence-based information. In this review, we highlight barriers to LDKT, define decision aids, describe strategies on how decision aids can overcome barriers to LDKT, and discuss the gaps and future research on and implementation of LDKT decision aids.

Barriers to Living Donor Kidney Transplantation

Barriers to LDKT are multifactorial [7], and include recipient and donor beliefs and characteristics [9–15], health care provider attitudes toward LDKT [16–18], and public opinion [19–21].

Recipient and donor barriers include limited knowledge of the benefits of transplantation (including benefits of LKDT over other forms of transplantation), psychological denial about the need for a transplant [7, 9, 10], cultural and religious concerns [11, 12], and financial concerns [13–15, 19, 22]. Potential recipients may turn down living donor kidney offers to protect the potential donor from incurring risks, or avoid asking people to donate because it is too challenging and/or may make others feel obligated to donate [8]. For living donors, financial barriers may affect LDKT [13, 15, 23]. A prospective study from seven Canadian transplant centers [15] stated 47% of living donors reported a loss of income with the average total out-of-pocket expenses and lost wages of $3,268.

Health care provider’s attitudes and perceptions of the appropriateness of LDKT for their patients may lead to lower LDKT rates and incomplete transplant evaluations [17, 18, 24]. Nephrologists who treat predominately minority ESRD populations spend less time providing patient education and counseling on LDKT compared to nephrologists with fewer minority patients [16], which may reflect providers’ attitudes about their patients’ suitability for transplant [24]. Provider perception of a potential recipient or donor’s reduced health care access and poor medical follow-up may also influence their attitude about the patient’s suitability for LDKT [7].

Public opinion toward LDKT is favorable, with the majority of the public (90%) considering LDKT an acceptable procedure and 76% [25] willing to consider potential living donation to a close friend [20, 25, 26]. However, negative attitudes and fear of the unknown remain in public opinion, and potential donors reported being weary about risks such as decreased life expectancy, lifestyle limitations, relationship tension, and psychological distress in the event of recipient death or graft loss [20, 21].

Among these barriers to LDKT, different subgroups may encounter different barriers in their access to LDKT [7, 8, 10, 27, 28].

Decision Aid Overview

Decision aids are evidence-based tools designed to help patients and their families participate in making specific choices, such as LDKT, among other healthcare options [29–32]. Decision aids are designed to supplement clinician counseling. In other healthcare settings, decision aids have been shown to improve knowledge [33–36], improve patient-practitioner communication [37, 38], and decrease decisional conflict [38–40] about treatment decisions. Decision aids prompt patient involvement in the health care decision-making process, which can contribute to better health outcomes [41–43].

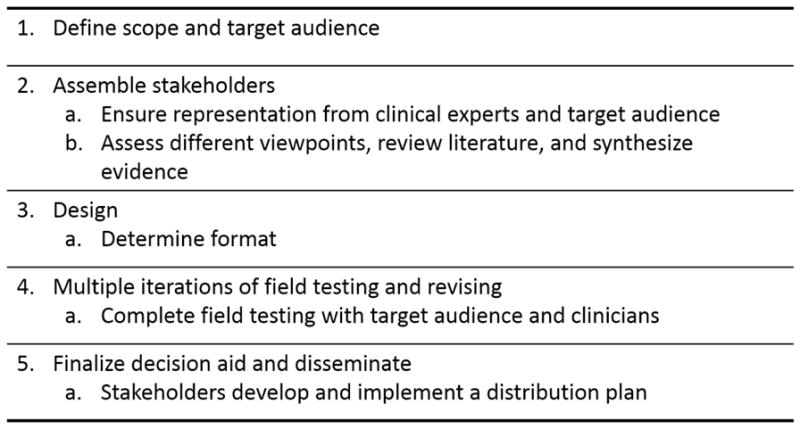

Decision aids can assume many forms such as a brochure, fact sheet, handbook, videos, website, smartphone applications, in-person, and social media applications. Across all forms, decision aids are developed through a process involving several steps. The development process presented by the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration entails: 1) defining the purpose and scope of the decision aid, 2) forming a steering committee comprised of clinical experts and patients, 3) assessing patient needs, determining dissemination of decision aid, and reviewing the synthesized evidence, 4) creating the first draft of the decision aid and completing alpha-testing, 5) revising the decision aid based on clinician and patient feedback, 6) beta-testing the decision aid, 7) reviewing clinician and patient feedback to revise decision aid, and 8) disseminating the decision aid [30] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Decision aid development process, adapted from the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Guidelines, with permission (2013) [30]

The American Society of Transplantation’s Live Donor Community of Practice held a Consensus Conference in 2014 to determine the best practices in educating patients and potential donors about LDKT [44]. The Live Donor Community of Practice’s educational recommended offering culturally-tailored information that provides evidence-based comparison of the risk and benefits on LDKT. The recommendations also included potential living donor educational material such as a summary of financial risks and estimation of costs [44]. Decision aids can be utilized by transplant centers to meet the Live Donor Community of Practice’s recommendation for education. We reviewed the literature and identified 12 decision aids (Table 1) that provide educational resources on and/or serve to increase LDKT. While some of these decision aids overlap across categories, we broadly classified the 12 decision aids across the following types: 1) comprehensive LDKT education, 2) culturally sensitive, targeted to specific audience, 3) recipient education, 4) potential donor recruitment and education, and 5) healthcare provider education. Four of these aids have completed evaluation and demonstrated effectiveness [45–48]. Six are undergoing effectiveness testing [49–54] (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary and brief description of decision aids focused on living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT)

| Decision Aid | Mode of Delivery | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive LDKT Education Decision Aids | ||

| Patients’ Readiness to make Decisions about Kidney Disease (PREPARED) | Handbook Mini-book Video Website | Information on overcoming knowledge and financial barriers. Video provides patient testimonials and ‘concerns’ from patients, patient family members, and healthcare professionals. |

| The Big Ask, The Big Give | Print materials Telephone help line Peer mentoring, Online Awareness Campaign Website | Provide ESRD patients, their family and friends, and potential kidney donors resources to learn about LDKT, tools to help those considering donation to make an informed choice, information about the transplant evaluation process and financial aspects of LDKT, and tips for ESRD patients on to find and communicate with a potential living donor. |

| Culturally Sensitive or Audience-Specific Decision Aids | ||

| Living About Choices in Transplantation and Sharing (Living ACTS) | Handbook DVD | Aimed at overcoming communication barriers related to living donor kidney transplantation, that is culturally-sensitive to African Americans. |

| Infόrmate: Inform Yourself About Living Kidney Donation for Hispanics/Latinos | Website | A culturally targeted, interactive, bilingual website aimed to increase knowledge about living donation and transplantation for Hispanic kidney disease patients and their families. |

| Decision Aids for Potential Recipients | ||

| Your Path to Transplant | Computer-Tailored Educational Messages (delivered with or without a Telephonic Health Coach) Brochures Fact Sheets Videos | Computerized program that generates individually-tailored educational messages based on assessments of individual patients’ LDKT readiness, self-efficacy, perceived pros and cons, knowledge, and socioeconomic barriers. Aimed to improve LDKT readiness, self-efficacy, transplant knowledge, and pursuit of LDKT. |

| Explore Transplant @ Home | Text messaging (delivered with or without a Health Coach) Brochures Fact Sheets Postcards Videos | Educational material on kidney transplantation that discuss the advantages of LDKT. Educational materials are mailed to participants and aims at improving patient knowledge, decision making, the balance of perceived pros over cons, and self-efficacy. |

| My Transplant Coach | iOS Application | iOS application that communicates patient-specific predictions on patient survival for different ESRD treatment options through animated videos and individualized charts. Promotes consideration of LDKT and aimed to improve patient empowerment and reduce anxiety. A shared decision aid which provides individualized risk predictions comparing short-term patient survival for kidney |

| iChoose Kidney | Website Smartphone Application | transplantation versus dialysis. iChoose assists providers in discussing treatment options with patients at the start of dialysis, and is available through a website or iOS mobile applications. |

| Decision Aids for Potential Donor Education and Recruitment | ||

| Live Donor Champion | In-person | Training offered to a recruited family member or friend of ESRD patient to serve as a patient advocate. |

| DONOR | Social Media Website (Facebook) | A social media application that provides a platform for the ESRD patient to share their narrative. Application prompts the patient to complete a series of questions that is used to create a story that is easily shared through the patient’s social network. |

| ESRD Risk Tool for Kidney Donor Candidates | Website | The aid is intended for potential living kidney donors. It provides a 15-year estimate and lifetime incidence of the potential donor being diagnosed with ESRD after donation. |

| Decision Aids for Healthcare Providers | ||

| Live Donor KDPI | Website | The Living Donor KDPI was designed to be used by healthcare professionals to determine the transplant recipients risk and allows the comparison of recipient outcomes with different living donors to find the more compatible match. The healthcare professional may use the decision aid to calculate the recipient’s LDKT risk compared to deceased donor kidney transplantation by inputting the potential donor’s clinical factors. |

Abbreviations: ESRD, end stage renal disease; KDPI, kidney donor profile index

Table 2.

Description of living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) decision aid characteristics, attributes, and methodologic rigor

| Accessibility | Culturally Sensitive | Intended Audience | Methodologic Rigor | Suitable Use During Transplant Process | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freely Accessible | Must Pay to Obtain | Patients | Potential Living Donors | Providers | Variety of stakeholders involved in development, including target audience | Effectiveness evaluated in target audience | Revised after multiple field testing | Pre-Dialysis | Dialysis Start | Transplant Referral | Transplant Evaluation | Waitlisting | ||

| Comprehensive LDKT Education Decision Aids | ||||||||||||||

| Patients’ Readiness to make Decisions about Kidney Disease (PREPARED) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | In Progress | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| The Big Ask, The Big Give | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | In Progress | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Culturally Sensitive or Audience-Specific Decision Aids | ||||||||||||||

| Living About Choices in Transplantation and Sharing (Living ACTS) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Infόrmate: Inform Yourself About Living Kidney Donation for Hispanics/Latinos | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Decision Aids for Potential Recipients | ||||||||||||||

| Your Path to Transplant | In Progress | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | In Progress | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Explore Transplant@ Home | In Progress | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | In Progress | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| My Transplant Coach | In Progress | ✓ | In Progress | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| iChoose Kidney | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | In Progress | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Decision Aids for Potential Donor Education and Recruitment | ||||||||||||||

| Live Donor Champion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | In Progress | ✓ | ||||||||

| DONOR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | In Progress | ✓ | ||||||||

| ESRD Risk Tool for Kidney Donor Candidates | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Decision Aids for Healthcare Providers | ||||||||||||||

| Live Donor KDPI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: ESRD, end stage renal disease; KDPI, kidney donor profile index

Comprehensive LDKT Education Decision Aids

Although Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) mandates that ESRD patients be informed of all treatment options within 45-days of starting dialysis [55], there are significant discrepancies between provider- and patient-reported patient education, with transplant education being reported by both patients and providers in only 56.2% of participants [56]. Despite the CMS mandate, only a minority of providers have a detailed discussion about kidney transplantation with patients [57]. Living donors desire additional information on LDKT beyond the CMS mandated specific information [58]. In addition to information on health risks, financial concerns such as out-of-pocket expenses, lost wages, and insurance obtainment after donation are important for potential recipients and potential donors [13, 15, 23]. Decision aids that address the benefits of transplant, the transplantation process, targeted questions to assist patients make decisions, and financial materials for potential recipients and potential living donors are helpful to understand the breadth of commitment. Two decision aids that provide a comprehensive LDKT education, including financial-related material, are identified and described below.

Providing Resources to Enhance African American Patients’ Readiness to Make Decisions about Kidney Disease (PREPARED)

The Providing Resources to Enhance African American Patients’ Readiness to Make Decisions about Kidney Disease (PREPARED) provides patients with kidney disease informational and financial materials through a video and handbook [59]. PREPARED was designed in two phases to adhere to the IPDAS Guidelines [30]. The decision aid was designed to address the risks and benefits of treatment options for kidney disease including peritoneal dialysis, in-center hemodialysis, home dialysis, transplant, and conservative management [59]. The comprehensive materials can be accessed on the web (http://ckddecisions.org/prepared-materials/) and consist of a 50-minute video, 159-page handbook, and 14-page mini-book “All of the Facts.” The video provides patient testimonials and concerns from patients, family members, and healthcare professionals. The handbook and mini-book are written at a 4th and 6th grade reading level and present a value clarification exercise to help patients determine which treatment they prefer [59]. PREPARED’s effectiveness to increase self-reported rates of LDKT consideration (clinicaltrials.gov protocol #NCT01439516) is currently being evaluated in a single center, randomized control trial (n=210) [50].

The Big Ask, The Big Give

In 2003, the National Kidney Foundation developed a comprehensive online resource (https://www.kidney.org/transplantation/livingdonors) that provides information on LDKT [51] and was ranked #1 among 86 LDKT online resources [60]. The resource is geared toward potential transplant recipients, potential living donors, family members, and healthcare professionals. After an overwhelming response from a 2014 living donor survey requesting a living donation campaign and more extensive online resources about donation and transplant, National Kidney Foundation developed “The Big Ask, The Big Give” awareness campaign [51]. In accordance with IPDAS guidelines, the National Kidney Foundation conducted a needs assessment with living donors and ESRD patients, field tested a website with their Kidney Advocacy Committee, and is being pilot tested in two sites in Georgia. The National Kidney Foundation plans a national dissemination of “The Big Ask, The Big Give” at conclusion of pilot testing. In the interim, “The Big Ask, The Big Give” website (https://www.kidney.org/transplantation/livingdonors/bigask and https://www.kidney.org/transplantation/livingdonors/biggive) remains available to patients, families, potential donors, and healthcare professionals.

Culturally Sensitive or Audience-Specific Decision Aids

Living About Choices in Transplantation and Sharing (Living ACTS)

Prior research has shown that African Americans have less awareness of the benefits and risks to donors of living donation, and have fewer potential living donors, compared to whites [7]. Living About Choices in Transplantation and Sharing (Living ACTS) [45] is a decision aid developed using the IPDAS Guidelines and aimed at overcoming communication barriers related to LDKT that are culturally-sensitive to African Americans. Living ACTS was adapted from a community project with local churches aimed to improve the public commitment to deceased donation [61]. Living ACTS is an educational and motivational DVD, supplemented by a booklet, that employed the Two-Dimensional Model of Cultural Sensitivity in Public Health [62] and conceptualizes cultural sensitivity using surface and deep structure. Living ACTS exemplifies surface structure by including people, places, and language important and familiar to the target audience while acknowledging the influential roles that family and family discussions have in African American healthcare decision making. Living ACTS’s single-center, randomized control, effectiveness trial (n=268) found that Living ACTS participants had significantly improved knowledge and willingness to talk with family members immediately after viewing the DVD and booklet; the increased knowledge and willingness were maintained at the 6-month follow-up [45].

Infόrmate: Inform Yourself About Living Kidney Donation for Hispanics/Latinos

Culturally targeted, Internet-based health interventions have been shown to be highly effective to train community health advisors [63], improve depressive symptoms [64], and increase smoking cessation [65]. Although the rate of Internet usage is comparable between Hispanics and non-Hispanics [66], few websites about kidney transplantation address the Hispanic community’s specific needs with regard to treatment options [67]. Infόrmate: Living Kidney Donation for Hispanics/Latinos (http://informate.org) is a culturally targeted, bilingual decision aid website designed to increase knowledge about living donation and transplantation for Hispanic kidney disease patients and their families and potential living donors [46]. The website [68] was developed, in partnership with the National Kidney Foundation of Illinois, following IPDAS guidelines using Resnicow’s Two-Dimensional Model of Cultural Sensitivity in Public Health [62]. Infόrmate was prepared at the 5th to 8th grade reading level, and engages users through interactive graphics that the user can click through to expose current medical advice on frequently asked questions. The website offers a quiz to assess knowledge of transplant myths versus facts and provides PDFs to download summarizing the myths versus facts, and the risks and benefits to living donor kidney transplantation [46]. Infόrmate hosts 19 living donor and recipient testimonials, 2 telenovelas, and 3 drag-and-drop games [68]. A prospective, multi-site randomized control trial (clinicaltrials.gov protocol #NCT01859871) of 282 patients and family members were exposed to 3 of 6 Infόrmate sections for a total of 30-minutes. Immediately following the intervention, participants showed significant increases in transplant and donation knowledge. These increases in knowledge were sustained at the 3-week follow-up [46]. Informate was also evaluated in a pretest-posttest among 63 dialysis patients and was shown to significantly increase LDKT knowledge [69].

Decision Aids for Potential Recipients

Your Path to Transplant

Patient-specific education may improve access to LDKT. Your Path to Transplant [52] is a computer-tailored intervention that generates individually-tailored educational messages to ESRD patients based on the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change [70], which holds that patients vary in their readiness to seek a transplant, and that educational messages should be matched to the patient’s stage of readiness. Your Path to Transplant includes personalized, telephonic coaching from experts trained in health communication, public health, psychology, or social work; supplemental educational materials, including videos, brochures and fact sheets, and feedback reports tailored to patients’ readiness, knowledge, self-efficacy, and perceptions of the pros and cons of transplant pursuit [1]. Your Path to Transplant aims to improve LDKT readiness, self-efficacy, balance of pros vs. cons, and knowledge, as well as pursuit of LDKT and ultimate receipt of LDKT. Your Path to Transplant’s effectiveness is currently being evaluated (clinicaltrials.gov protocol #NCT02181114) through a randomized control trail of 900 transplant patients [52].

Explore Transplant @ Home

Given that the majority (57%) of nephrologists spend <20 minutes educating their patients on transplant [71], alternative patient-education that can be completed at home or via telephone may be needed to help dialysis patients learn about transplant [72, 73]. Explore Transplant @ Home is a patient-education program that involves mailing home informational brochures, postcards, fact sheets, as well as four 20 minute videos to dialysis patients. In addition, motivational, interactive text messages that explain the benefits and risks of dialysis, deceased donor transplant and LDKT are sent to patients [53]. In a current randomized control trial, the effectiveness of the Explore Transplant @ Home (clinicaltrials.gov protocol #NCT02268682) program on its own is being compared to use of the program supplemented by telephone support from a trained educator was provided to patients [6]. Explore Transplant @ Home modules were designed to be administered gradually and incrementally based on the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change [70].

My Transplant Coach

The decision to remain on dialysis, accept different deceased donor kidneys, or pursue living donation is a complex one. The standard of care at many transplant centers is to communicate average, population-based, non-tailored prognosis estimates to individual ESRD patients, if these estimates are communicated at all [5]. In a study among 388 incident dialysis patients, kidney transplantation provision of information was concordantly reported by both the nephrologist and patient 56.2% [56]. Among those patients uninformed about transplantation, only 3% were listed for a kidney transplant [56]. In order to improve patient empowerment and education about all their treatment options, an iOS tablet application, My Transplant Coach, was designed by transplant surgeons, nephrologists, and medical educators. The tablet-based decision aid communicates pre-transplant mortality rate, median waiting time to kidney transplantation, and post-transplant patient survival through didactic, animated videos of diverse patients and donors learning, with professional voice-over performances, simulating the transplant evaluation process [54]. The application was designed to be culturally competent and usable by patients with low health literacy and numeracy. The effectiveness of My Transplant Coach is in progress. Preliminary data from a pilot study of 81 patients across two U.S. transplant centers, 78% of participants reported that My Transplant Coach made them more comfortable to talking to their healthcare providers about transplant. My Transplant Coach significantly increased participants transplant knowledge pre- and post-intervention [54].

iChoose Kidney

Similar to a decision aid, shared decision making is a process of making a healthcare decision jointly by the patient, family, and healthcare provider [74–76]. The shared decision making model integrates the healthcare provider’s clinical expertise with patient values and beliefs to facilitate informed, joint healthcare decisions [75–77]. Shared decision aids are tools that may be utilized during shared decision making, and can help promote patient-centered care [78]. iChoose Kidney was developed as a shared decision aid for clinicians to discuss with patients individualized risk predictions comparing short-term patient survival for kidney transplantation versus dialysis [79]. A multidisciplinary team developed iChoose Kidney to assists providers in discussing treatment options with patients at the start of dialysis, and is available through the Internet (http://ichoosekidney.emory.edu/) or a mobile (iOS) app. iChoose Kidney presents the patient survival or mortality risk in a patient-friendly manner using both graphical and numeric representations [80]. iChoose Kidney followed the IPDAS guidelines [30] for decision aid development, and best practices were used to ensure access for patients with low health literacy and numeracy [29, 81]. The effectiveness of iChoose Kidney (clinicaltrials.gov protocol #NCT022355571) to increase knowledge regarding the transplant survival benefit compared to dialysis is currently being evaluated in a multicenter, randomized control trial among transplant candidates (n=450) presenting at transplant evaluation [49].

Decision Aids for Potential Donor Education and Recruitment

Transplant candidates are reluctant to discuss their illness and dialysis experience, which may hinder their pursuit of LDKT [82–84], and recruitment of potential living donors. Friends and family members are more eager to share the patient’s story and spread awareness about their loved one’s difficulties and needs [85]. Three decision aids have been developed to assist the recipient and their social network to recruit potential living donors.

Live Donor Champion

The Live Donor Champion is a decision aid that separates the living donor advocate from the transplant candidate [48] by recruiting a friend or family member of the transplant candidate as the ‘champion’. The Live Donor Champion decision aid is intended to be delivered by transplant centers to help transplant candidates advocate for the recipients’ health and overcome their reluctance to ‘ask for a favor’. In a prospective pilot study at one transplant center, 15 waitlisted patients were asked to identify one Live Donor Champion. A matched control patient was identified for each intervention patient; patients were matched on age, sex, blood type, cause of ESRD, diabetes diagnosis, time on the waiting list, and education level [86, 87]. Live Donor Champions completed 5 trainings over a 6-month period that addressed common transplant barriers and best practice methods for initiating conversations about living donor kidney transplantation [48]. Live Donor Champions were found to be more comfortable initiating conversations with family and friends over time. Patients with a Live Donor Champion were significantly more likely to have more live donor inquiries to the transplant center and more LDKTs compared to matched controls [48].

DONOR

A smartphone app, DONOR, was developed in line with IPDAS development guidelines and in collaboration with Facebook, to allow the transplant candidate to comfortably and indirectly share their narrative [47] through a series of prompted questions. Similar to other Facebook apps focused on organ donation [88], DONOR includes links to educational resources on transplantation that have been vetted by transplant ethicists. The narrative and transplant educational links can be uploaded to the transplant candidate’s Facebook page and easily shared by the candidate’s social network. In a single-center, prospective cohort study of the DONOR app, 54 adult kidney-only or liver-only waitlisted patients created and posted their patient stories on Facebook. In total, the Facebook posts generated >400 of ‘likes’ and shares within 1 month of the initial session, and 18 potential live donors contacted the transplant center on behalf of the participants, significantly more than their matched controls [47].

ESRD Risk Tool for Kidney Donor Candidates

In addition to donor recruitment, potential donors should be informed of the health risks associated with LDKT. While Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) mandate specific information be communicated to potential living donors [58], living donors reported the CMS information only moderately helpful [23]. A national study of >96,000 live kidney donors documented a slightly higher risk of developing ESRD among live kidney donors compared to healthy controls [89]. While the lifetime risk of ESRD is no higher than the general demographics-matched US population, the live kidney donors should be educated about the risk. The end-stage renal disease (ESRD) Risk Tool for Kidney Donor Candidates is freely available online (http://www.transplantmodels.com/esrdrisk/) and calculates individualized-risk estimates for ESRD for potential donors [90]. The risk equations were based on >4,933,000 patients from seven U.S. cohorts. Risk equations were applied to 57,508 living kidney donors to calculate 15-year and lifetime ESRD incidence estimates [90] based on 10 pre-donation health and demographic characteristics.

Decision Aids for Healthcare Providers

Live Donor KDPI

The Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) was designed to classify deceased donor characteristics and estimate the risk of graft failure to the deceased donor kidney transplant recipient [91, 92]. Massie et al designed a similar risk index to classify living donor kidneys to enable health professionals to quantify the health risk for their recipient [93]. The Live Donor KDPI was designed using the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) data system and the study population consisted of all adult first-time, kidney-only transplant recipients between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2013. Thirteen characteristics were included in the final model and included characteristics such as donor’s age, sex, body mass index, history of cigarette use, recipient’s sex, and donor:recipient ABO-compatibility and HLA-mismatch [93]. The Live Donor KDPI is freely available online (http://www.transplantmodels.com/lkdpi/) and is intended to guide healthcare providers to determine the potential transplant recipients’ risk and enables comparison of recipient outcomes with different living donors to find the more compatible live donor for their recipient.

Remaining Gaps of Current Decision Aids

Our review included 12 decision aids for LDKT interventions that met the definition of a decision aid. There are other significant LDKT interventions, rather than decision aids, available to potential recipients and potential donors that were not described above. Rodrigue et al.’s House Calls trial [94] is one example of an innovative approach focusing on increasing living donation among African Americans that delivers personalized education in the potential recipient’s or family member’s home. In the House Call effectiveness trial, the primary outcome is occurrence of LDKT and participants (n=180) assigned to House Calls are encouraged to invite close family, friends, co-workers to a culturally sensitive, education session led by a trained health educator [94]. At the end of a 2-year follow-up, participants of the House Calls intervention were more likely to have living donor inquiries and evaluation [73]. House Calls’ home-based group education approach was adapted to the Dutch population for ESRD patients who were unable to find a living donor [95]. The “Kidney Team at Home” provides an in-person consultation with a home educator for ESRD patients and their family and friends. The educators discussed verbal and written information on five concepts: 1) kidney disease overview, 2) dialysis, 3) kidney transplantation advantages, disadvantages, and the transplant process, 4) LKDT, and 5) open discussions on whether the individuals present have considered LDKT. “Kidney Team at Home” participants showed improved knowledge and attitudes toward LDKT, and more LDKTs compared to participants randomized to standard care [95].

For donors and potential donors, the American Society of Transplantation’s Live Donor Financial Toolkit [96] is an important online resource targeting potential living donors (https://www.myast.org/patient-information/live-donor-toolkit). The Live Donor Financial Toolkit includes eight chapters to educate the potential donor on estimated LKDT-associated costs, various funding programs that donors can apply to for financial assistance, frequently asked questions on fundraising and insurance, and legislative efforts and federal laws that exist related to LDKT [96]. Another intervention targeted to donors or potential donors is an E-health cognitive behavioral therapy [97, 98]. The E-health cognitive behavior therapy is aimed to help donors or potential donors overcome feelings of ambivalence toward their donation decision and includes treatment modules on negative mood, social functioning, and communication to explore their feelings and thoughts about the donation decision [97].

While our review is not a comprehensive list of LDKT interventions available to the kidney transplantation community, we have summarized the existing decision aids described in the literature that may help improve access to LDKT. Our review noted common limitations and gaps that exist in the decision aids presented above, according to the IDPAS guidelines [30] (Table 2). As presented in Figure 1, the crux of the IPDAS Guidelines is: 1) clearly defining the scope and target audience of the decision aid, 2) assembling stakeholders that include clinical experts and members of the intended audience to assist in development, and 3) repeated field testing and revising of the decision aid. The IPDAS Guidelines emphasize careful planning to assure decision aid users of the reliability and validity of the tool.

The IPDAS Guidelines stress that decision aids must be carefully developed and tested by the users [30]. Involving a variety of stakeholders strengthens the internal validity and assures the decision aid is accomplishing the defined scope, reaching the target audience, and is being tested using appropriate effectiveness measures [30]. Stakeholders can also address potential barriers to implementing or using the decision aid. Few LDKT decision aids presented detailed information on the stakeholder’s involved [45, 53, 68, 79] and seldom reported if members of the target audience were involved in the LDKT decision aid development [29]. The peer review community should recognize the value of stakeholder involvement and importance of careful development and encourage investigators to report equally on those characteristics.

Four of the reviewed LDKT decision aids had evaluated their effectiveness. Six LDKT decision aids were in the process of evaluating their effectiveness. The IPDAS guidelines state the development process of decision aids should consist of multiple field tests and revisions, ultimately leading to distribution [30]. While six (54.5%) decision aids communicated their decision aid development process [45–47, 51, 59, 79], repeated field tests, revisions, and evaluations are needed to determine the long term impact of the LDKT decision aids. Investigators should build into their grant applications the need for additional testing, and funders should support such diligence in decision aid development. By assembling a group of stakeholders, including clinical experts and patients, a priori, investigators can plan for ongoing development within different sample populations that vary based on age, racial/ethnic background, and socioeconomic status. Effectiveness and usability testing in various populations will limit selection bias while enhancing the decision aid’s generalizability. Long-term evaluation will also offer insights into decision aids’ sustainable effects [88]. Researchers are encouraged to practice large-scale collaboration [99] and share ideas to improve research findings and reproducibility. Through collaboration, transplant centers may learn from other’s best practices to improve their clinical processes and reduce the national variation in LDKT education [100].

Conclusion

As the prevalence of ESRD continues to increase [3], LDKT could shorten the wait time for many patients and improve their survival. While patients, potential donors, and healthcare professionals encounter barriers to LDKT, various decision aids have been developed, tested, and are now available to assist patients and their families in making decisions about LDKT. Despite the extensive material provided to the ESRD community through several LDKT decision aids, some gaps remain in the development, effectiveness testing, and generalizability to a wider audience. In compliance with IPDAS Guidelines, investigators are encouraged to assemble stakeholders that encompass experts and members of the target audience. Transplant centers are also encouraged to collaborate and develop overarching best practices aimed at improving access to LDKT.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Jennifer Gander and Elisa Gordon declare no conflict of interest.

Rachel Patzer reports development of the iChoose Kidney tool, which is one of the decision aids described in this review article.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Laupacis A, et al. A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney international. 1996;50(1):235–242. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan JC, et al. Living donor kidney transplantation: facilitating education about live kidney donation—recommendations from a consensus conference. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015;10(9):1670–1677. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.System, U.S.R.D. USRDS 2015 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. National Institute of Health; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger JC, et al. Living kidney donors ages 70 and older: recipient and donor outcomes. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2011;6(12):2887–2893. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04160511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.System, U.S.R.D. U S Renal Data System. USRDS 2013 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharing, u.N.O. Transplant trends. 2015 [cited 2016; Available from: https://www.unos.org/data/transplant-trends/

- 7.Purnell TS, Hall YN, Boulware LE. Understanding and overcoming barriers to living kidney donation among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2012;19(4):244–251. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon EJ. “They don't have to suffer for me”: why dialysis patients refuse offers of living donor kidneys. Medical anthropology quarterly. 2001;15(2):245–267. doi: 10.1525/maq.2001.15.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lunsford SL, et al. Racial differences in coping with the need for kidney transplantation and willingness to ask for live organ donation. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2006;47(2):324–331. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boulware LE, et al. Identifying and addressing barriers to African American and non—African American families' discussions about preemptive living related kidney transplantation. Progress in Transplantation. 2011;21(2):97–104. doi: 10.1177/152692481102100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez LM, et al. Organ donation in three major American cities with large Latino and black populations. Transplantation. 1988;46(4):553–557. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198810000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alden DL, Cheung AH. Organ donation and culture: a comparison of Asian American and European American beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30(2):293–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke KS, et al. The direct and indirect economic costs incurred by living kidney donors—a systematic review. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2006;21(7):1952–1960. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ommen E, Gill J. The system of health insurance for living donors is a disincentive for live donation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2010;10(4):747–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klarenbach S, et al. Economic Consequences Incurred by Living Kidney Donors: A Canadian Multi-Center Prospective Study. American Journal of Transplantation. 2014;14(4):916–922. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balhara K, et al. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF TRANSPLANTATION. WILEY-BLACKWELL COMMERCE PLACE; 350 MAIN ST, MALDEN 02148, MA USA: 2011. Race, age, and insurance status are associated with duration of kidney transplant counseling provided by non-transplant nephrologists. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayanian JZ, et al. Physicians’ beliefs about racial differences in referral for renal transplantation. American journal of kidney diseases. 2004;43(2):350–357. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghahramani N. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF TRANSPLANTATION. WILEY-BLACKWELL COMMERCE PLACE; 350 MAIN ST, MALDEN 02148, MA USA: 2011. Perceptions of patient suitability for kidney transplantation: a qualitative study comparing rural and urban nephrologists. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulware L, et al. The general public's concerns about clinical risk in live kidney donation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2002;2(2):186–193. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.020211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong A, et al. Public attitudes and beliefs about living kidney donation: focus group study. Transplantation. 2014;97(10):977–85. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong A, et al. Public awareness and attitudes to living organ donation: systematic review and integrative synthesis. Transplantation. 2013;96(5):429–437. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31829282ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang R, et al. Insurability of living organ donors: a systematic review. American Journal of Transplantation. 2007;7(6):1542–1551. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Traino HM, et al. Living Kidney Donors' Information Needs and Preferences. Prog Transplant. 2016;26(1):47–54. doi: 10.1177/1526924816633943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanson CS, et al. Nephrologists' Perspectives on Recipient Eligibility and Access to Living Kidney Donor Transplantation. Transplantation. 2016;100(4):943–53. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spital A. Public attitudes toward kidney donation by friends and altruistic strangers in the United States. Transplantation. 2001;71(8):1061–1064. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200104270-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fellner CH, Schwartz SH. Altruism in disrepute: medical versus public attitudes toward the living organ donor. New England Journal of Medicine. 1971;284(11):582–585. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197103182841105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weng FL, et al. Barriers to living donor kidney transplantation among black or older transplant candidates. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2010;5(12):2338–2347. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03040410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvaro EM, et al. Living kidney donation among Hispanics: a qualitative examination of barriers and opportunities. Progress in Transplantation. 2008;18(4):243–250. doi: 10.1177/152692480801800406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elwyn G, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. Bmj. 2006;333(7565):417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **30.Coulter A, et al. A systematic development process for patient decision aids. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S2. The study presents a detailed model development process for decision aids that can be applied across healthcare fields. Guidelines are aimed to reduce decision aid bias and improve generalizability. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joseph-Williams N, et al. Toward Minimum Standards for Certifying Patient Decision Aids A Modified Delphi Consensus Process. Medical Decision Making. 2014;34(6):699–710. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13501721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stacey D, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. The Cochrane Library; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans R, et al. Supporting informed decision making for prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing on the web: an online randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research. 2010;12(3):e27. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamann J, et al. Shared decision making and long-term outcome in schizophrenia treatment. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2007;68(7):992–997. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathieu E, et al. Informed choice in mammography screening: a randomized trial of a decision aid for 70-year-old women. Archives of internal medicine. 2007;167(19):2039–2046. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trevena LJ, Irwig L, Barratt A. Randomized trial of a self-administered decision aid for colorectal cancer screening. Journal of medical screening. 2008;15(2):76–82. doi: 10.1258/jms.2008.007110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montori VM, et al. Use of a decision aid to improve treatment decisions in osteoporosis: the osteoporosis choice randomized trial. The American journal of medicine. 2011;124(6):549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weymiller AJ, et al. Helping patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus make treatment decisions: statin choice randomized trial. Archives of internal medicine. 2007;167(10):1076–1082. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frosch DL, et al. Internet patient decision support: a randomized controlled trial comparing alternative approaches for men considering prostate cancer screening. Archives of internal medicine. 2008;168(4):363–369. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaner E, et al. Medical communication and technology: a video-based process study of the use of decision aids in primary care consultations. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2007;7(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith SK, et al. Exploring patient involvement in healthcare decision making across different education and functional health literacy groups. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(12):1805–12. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Connor AM, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(1):6–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1209500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **44.LaPointe Rudow D, et al. Consensus conference on best practices in live kidney donation: recommendations to optimize education, access, and care. American Journal of Transplantation. 2015;15(4):914–922. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13173. The paper details the transplant community's commitment to improving living donor kidney transplanation through various strategies and initiatives. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arriola KRJ, et al. Living donor transplant education for African American patients with end-stage renal disease. Progress in Transplantation. 2014;24(4):362–370. doi: 10.7182/pit2014830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gordon EJ, et al. A Culturally Targeted Website for Hispanics/Latinos About Living Kidney Donation and Transplantation: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Increased Knowledge. Transplantation. 2016;100(5):1149–1160. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar K, et al. A Smartphone App for Increasing Live Organ Donation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ajt.13961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garonzik-Wang JM, et al. Live donor champion: finding live kidney donors by separating the advocate from the patient. Transplantation. 2012;93(11):1147. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31824e75a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patzer RE, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Mobile Clinical Decision Aid to Improve Access to Kidney Transplantation: iChoose Kidney. Kidney International Reports. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ephraim PL, et al. The providing resources to enhance African American patients’ readiness to make decisions about kidney disease (PREPARED) study: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC nephrology. 2012;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Foundation NK. The Big Ask, The Big Give. 2016 [cited 2016 August 04, 2016]; Available from: www.kidney.org/livingdonation.

- 52.Waterman AD, et al. Your path to transplant: a randomized controlled trial of a tailored computer education intervention to increase living donor kidney transplant. BMC nephrology. 2014;15(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waterman AD, et al. Explore Transplant at Home: a randomized control trial of an educational intervention to increase transplant knowledge for Black and White socioeconomically disadvantaged dialysis patients. BMC nephrology. 2015;16(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0143-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson C, Wojciechowski AD, Jacobs M, Lentine K, Schnitzler M, Peipert JD, Waterman A. American Society of Nephrology. 2016. Cultural Competency of a Mobile, Customized Patient Education Tool for Improving Potential Kidney Transplant Recipients’ Knowledge and Decision- Making; p. TH-OR098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Medicare Cf H. Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid programs; conditions for coverage for end-stage renal disease facilities. Final rule. Federal register. 2008;73(73):20369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salter ML, et al. Patient-and provider-reported information about transplantation and subsequent waitlisting. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014;25(12):2871–2877. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013121298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waterman AD, et al. Assessing transplant education practices in dialysis centers: Comparing educator reported and Medicare data. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015;10(9):1617–1625. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09851014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Medicare, C.f. and H. Medicaid Services. Medicare program; hospital conditions of participation: requirements for approval and re-approval of transplant centers to perform organ transplants. Final rule. Federal register. 2007;72(61):15197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ameling JM, et al. Development of a decision aid to inform patients’ and families’ renal replacement therapy selection decisions. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2012;12(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moody E, et al. Improving on-line information for potential living kidney donors. Kidney international. 2007;71(10):1062–1070. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arriola K, et al. Project ACTS: an intervention to increase organ and tissue donation intentions among African Americans. Health Education & Behavior. 2010;37(2):264–274. doi: 10.1177/1090198109341725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Resnicow K, et al. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethnicity & disease. 1998;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Santos SLZ, et al. Feasibility of a Web-Based Training System for Peer Community Health Advisors in Cancer Early Detection Among African Americans. American journal of public health. 2014;104(12):2282–2289. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ince BÜ, et al. Internet-based, culturally sensitive, problem-solving therapy for Turkish migrants with depression: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical internet research. 2013;15(10):e227. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi WS, et al. Culturally-tailored smoking cessation for American Indians: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zickuhr K. Who’s not online and why. Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2013. p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gordon EJ, et al. Quality of Internet education about living kidney donation for Hispanics. Progress in Transplantation. 2012;22(3):294–303. doi: 10.7182/pit2012802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gordon EJ, et al. An interactive, bilingual, culturally targeted website about living kidney donation and transplantation for hispanics: development and formative evaluation. JMIR research protocols. 2014;4(2):e42–e42. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gordon EJ, et al. A Website Intervention to Increase Knowledge About Living Kidney Donation and Transplantation Among Hispanic/Latino Dialysis Patients. Progress in Transplantation. 2016;26(1):82–91. doi: 10.1177/1526924816632124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Prochaska J, et al. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. 2002:60–84. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Balhara K, et al. Disparities in provision of transplant education by profit status of the dialysis center. American Journal of Transplantation. 2012;12(11):3104–3110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmittdiel JA. Health-plan and employer-based wellness programs to reduce diabetes risk: The Kaiser Permanente Northern California NEXT-D Study. Preventing chronic disease. 2013:10. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rodrigue JR, et al. Making house calls increases living donor inquiries and evaluations for blacks on the kidney transplant waiting list. Transplantation. 2014;98(9):979. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean?(or it takes at least two to tango) Social science & medicine. 1997;44(5):681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Towle A, Godolphin W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. British Medical Journal. 1999;319(7212):766. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Légaré F, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. The Cochrane Library; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gordon E, et al. Opportunities for shared decision making in kidney transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2013;13(5):1149–1158. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hurtado MP, Swift EK, Corrigan JM. Envisioning the national health care quality report. National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patzer RE, et al. iChoose Kidney: A Clinical Decision Aid for Kidney Transplantation Versus Dialysis Treatment. Transplantation. 2016;100(3):630–639. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reyna VF. A theory of medical decision making and health: fuzzy trace theory. Medical Decision Making. 2008 doi: 10.1177/0272989X08327066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lipkus IM. ONLINE COLOR_Numeric, Verbal, and Visual Formats of Conveying Health Risks: Suggested Best Practices and Future Recommendations. Medical Decision Making. 2007 doi: 10.1177/0272989X07307271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burroughs TE, Waterman AD, Hong BA. One organ donation, three perspectives: experiences of donors, recipients, and third parties with living kidney donation. Progress in Transplantation. 2003;13(2):142–150. doi: 10.1177/152692480301300212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hays R, Waterman AD. Improving preemptive transplant education to increase living donation rates: reaching patients earlier in their disease adjustment process. Progress in Transplantation. 2008;18(4):251–256. doi: 10.1177/152692480801800407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Waterman AD, et al. Potential living kidney donors' health education use and comfort with donation. Progress in Transplantation. 2004;14(3):233–240. doi: 10.1177/152692480401400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Glazier AK, Sasjack S. Should It Be Illicit to Solicit-A Legal Analysis of Policy Options to Regulate Solicitation of Organs for Transplant. Health Matrix. 2007;17:63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Segev DL, et al. Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. Jama. 2010;303(10):959–966. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Montgomery RA, et al. Desensitization in HLA-incompatible kidney recipients and survival. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(4):318–326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cameron AM, et al. Social media and organ donor registration: the Facebook effect. American Journal of Transplantation. 2013;13(8):2059–2065. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Muzaale AD, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. Jama. 2014;311(6):579–586. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Grams ME, et al. Kidney-failure risk projection for the living kidney-donor candidate. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(5):411–421. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gupta A, Chen G, Kaplan B. KDPI and donor selection. American Journal of Transplantation. 2014;14(11):2444–2445. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rao PS, et al. A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: the kidney donor risk index. Transplantation. 2009;88(2):231–236. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ac620b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Massie AB, et al. A risk index for living donor kidney transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ajt.13709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rodrigue JR, et al. The “House Calls” trial: a randomized controlled trial to reduce racial disparities in live donor kidney transplantation: rationale and design. Contemporary clinical trials. 2012;33(4):811–818. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ismail S, et al. Home-Based Family Intervention Increases Knowledge, Communication and Living Donation Rates: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Transplantation. 2014;14(8):1862–1869. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Transplantation, A.S.o. Live Donor Financial Toolkit. [cited 2016 August 23, 2016]; Available from: https://www.myast.org/patient-information/live-donor-toolkit.

- 97.Wirken LvMH, Hooghod Y, Hopman S, Hoitsma A, Hilbrands L, Evers A. Tailored E-Health Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Livind Kidney Donors at Risk. 4th Ethical, Legal and Psychosocial Aspects of Transplantation Global Challenges. 2016:85–86. [Google Scholar]

- 98.van Beugen S, et al. Tailored Therapist-Guided Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Treatment for Psoriasis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2016;85(5):297–307. doi: 10.1159/000447267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ioannidis JP. How to make more published research true. PLoS Med. 2014;11(10):e1001747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Reese P, et al. Substantial variation in the acceptance of medically complex live kidney donors across US renal transplant centers. American Journal of Transplantation. 2008;8(10):2062–2070. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]