Abstract

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is curable in 70–80% of patients with first-line therapy. However, relapses occur in a minority of patients with favorable early stage disease and are more frequent in patients with advanced HL. Salvage chemotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) for patients with chemotherapy-sensitive disease is a standard treatment sequence for relapsed or refractory (rel/ref) HL. Patients who achieve complete response prior to ASCT have better survival outcomes. The choice of salvage chemotherapy therapy is becoming increasingly difficult in the era of novel agents, as there are no randomized studies to guide the choice of a second-line regimen. In this article, we will review current salvage therapy options, including combination chemotherapy and novel-agent-based salvage regimens for rel/ref HL.

Keywords: relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma

Introduction

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) accounts for about 10% of all lymphomas, with approximately 9000 new cases in the United States in 2013 and 1200 deaths.1 HL shows bimodal distribution of patients diagnosed between 15 and 30 years of age and in adults older than 55 years of age. The disease is curable in approximately 70–80% of patients with long-term overall survival rates of over 70% at 5 years in patients treated with standard chemotherapy regimens, including adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) or Stanford V.2–4 However, relapses occur in 10–20% of patients with favorable features and early stage disease (stage I–II) and 30–40% of patients with advanced disease.5 Standard treatment for patients with relapsed or primary refractory (rel/ref) HL is salvage chemotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy (HDT) and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in chemotherapy-sensitive patients. The two randomized phase III clinical trials by the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (GHSG)/European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and British National Lymphoma Investigators demonstrated significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) for patients with relapsed or refractory HL who underwent HDT/ASCT as compared with conventional second-line chemotherapy alone. Complete response (CR) to salvage therapy prior to ASCT is the strongest prognostic factor for post-ASCT outcome, with patients in CR at the time of ASCT having significantly superior PFS compared with patients not in CR.6–11 Overall response rates (ORRs) and CR rates vary according to salvage regimen and also based on whether positron emission tomography (PET) or computed tomography (CT) imaging was used for evaluation of response. Response status based on functional imaging with PET prior to ASCT had predictive values by identifying patients as poor risk if PET was positive after the salvage regimen.9,12,13 In this article, we will review current salvage therapy options for rel/ref HL, including combination chemotherapy regimens and salvage regimens containing novel agents.

Chemotherapy-based salvage treatment options for patients relapsing after first-line therapy

Chemotherapy-based salvage regimens can achieve responses in 70–90% of patients with rel/ref HL. The most commonly used second-line regimens for patients with rel/ref HL include platinum-based and gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy, and are listed in Table 1. Platinum-based chemotherapy regimens are frequently utilized as second-line regimens for rel/ref HL, with ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) likely representing the most commonly used regimen in practice. Studies of ICE have demonstrated an ORR range of 88–100% and CR rate range of 26–67% assessed by PET-CT scan in one study. Event-free survival for patients in CR after ICE was 83% at 23 months follow up for patients with HL.14,15 DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin) is another commonly utilized platinum-based salvage regimen with a reported ORR of 89% and 21% CR rate in patients with rel/ref HL.16,17 A study by Sasse and colleagues demonstrated inferior PFS and OS if initiation of the second cycle of DHAP was delayed beyond 21 days from the initial dose of DHAP therapy, even after adjusting for hematologic toxicity and advanced disease.17 ESHAP (etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine and cisplatin) also showed compatible responses with an ORR of 73% and 40% CR, with myelosuppression observed as a dose-limiting grade 3–4 toxicity in 59% receiving this regimen.18

Table 1.

Salvage regimens for relapsed classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

| Regimen | Number of patients | Median age (range) years | Number of prior lines of therapy | Number of patients with prior ASCT | ORR (%) | CR (%) | Survival | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy-based regimens | ||||||||

| ICE | 65 | 27 (12-59) | 1-6 | NA | 88 | 26 | EFS 82% for patients in CR after ICE at 43 months follow up | 14 |

| ICE | 6 | 52 (30-65) | 1-2 | NA | 100 | 67 | 5/6 in CR at 23 months of follow up | 15 |

| DHAP | 102 | 34 (21-64) | 1 | NA | 89 | 21 | NR | 16 |

| ESHAP | 22 | 34 (18-66) | 1 | 2 | 73 | 40 | Actuarial OS and DFS 35% and 27% at 3 years | 18 |

| GVD | 91 | 33 (19-83) | 1 | 36 | 70 | 19 | 4-year EFS 52 % and OS 70% after GVD and ASCT Prior ASCT relapse: 4-year EFS 10% and OS 34% with GVD |

19 |

| IGEV | 91 | 30 (17-59) | 1-4 | NA | 81 | 54 | 3-year FFP 53% and OS 70% | 20 |

| GDP | 23 | 36 (19-57) | 1 | NA | 70 | 17 | NR | 21 |

| GemOx | 24 | 27 (14-76) | 1-6 | 10 | 71 | 38 | Median OS 99 months and PFS not reached for patients in CR | 22 |

| BeGEV | 59 | 33 (18-68) | 1 | NA | 83 | 73 | 2-year OS 62% and PFS 78% | 25 |

| Novel agent-based therapy | ||||||||

| Sequential BV-chemo | 37 | 34 (11-67) | 1 | NA | 68 | 35 | NR | 29 |

| Sequential BV-chemo (ICE) | 44 | 31 (13-65) | 1 | NA | NR | 27 (BV alone) 76 (overall) |

2-year EFS 80% (2-year EFS 91-92% for PET negative and 46% for PET positive prior to transplant); OS 95% | 31 |

| BV-ESHAP | 66 | 36 (18-66) | 1 | NA | 96 | 70 | 1-year projected OS 90% and PFS 87% | 32 |

| BV-ICE | 16 | 32 (23-60) | 1 | NA | 94 | 69 | 3 (19%) relapses during median follow up of 6.5 months | 33 |

| BV-DHAP | 12 | 30.5 (NR) | 1 | NA | 100 | 100 | All patients are in CR at median follow up of 15.4 months | 34 |

| BV-bendamustine | 55 | 36 (19-79) | 1 | NA | 93 | 74 | 1-year estimated PFS 80% | 35 |

| BV-nivolumab | 29 | 32 (18-69) | 1 | NA | 90 | 62 | NR | 38 |

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; BeGEV, bendamustine, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine; BV, brentuximab vedotin; CR, complete response; DHAP, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin; DFS, disease-free survival; EFS, event-free survival; ESHAP, etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine and cisplatin; FFP, freedom from progression; GDP, gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin; GemOx, gemcitabine and oxaliplatin; GVD, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, liposomal doxorubicin; ICE, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide; IGEV, ifosfamide, gemcitabine, etoposide, vinorelbine; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Gemcitabine-based combinations are also commonly used as second-line or third-line salvage regimens, including GVD (gemcitabine, vinorelbine, liposomal doxorubicin) which produced an ORR of 70% and 19% CR (by CT only) in patients with rel/ref HL.19 IGEV (ifosfamide, gemcitabine, etoposide, vinorelbine) is another highly effective gemcitabine-based salvage regimen with a reported ORR 81% and CR rate of 54% (response assessment by PET).20 GDP (gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin) and GemOx (gemcitabine and oxaliplatin) are other gemcitabine-based combinations with studies reporting an ORR of 70% with 17% CR (by CT) for GDP21 and an ORR of 71% and 38% CR for GemOx.22 Patients who fail a platinum-based salvage regimen might benefit from gemcitabine-based salvage. For example, GemOx produced an ORR of 44% with an 8% CR rate in such a population of patients.23

Bendamustine is an alkylating agent which has shown activity in relapsed HL, with an ORR of over 50% as a single agent in heavily pretreated patients.24 A recent multicenter phase II study evaluated a combination of bendamustine, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine (BeGEV) as second-line therapy in 59 patients with relapsed or refractory HL. The observed ORR was 83% and 73% of patients achieved CR. The most commonly observed grade 3 or 4 adverse events were febrile neutropenia, infections, thrombocytopenia and neutropenia.25

Novel agent-based salvage regimens prior to ASCT

In recent years, novel agents that are highly effective for the treatment of rel/ref HL have begun to be incorporated into earlier lines of therapy, including the second-line salvage setting. Brentuximab vedotin (BV) is an anti-CD30 antibody conjugated to an auristatin (MMAE), an antitubulin agent, and is highly effective for the treatment of rel/ref HL. BV binds to CD30 and after being internalized it releases MMAE, which subsequently binds to tubulin and leads to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. The most notable side effect of BV is peripheral neuropathy, occurring in 22% of patients, but neutropenia (22%), pyrexia (33%) and fatigue (36%) are also commonly observed.26 Rare cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy due to John Cunningham (JC) virus infection have been reported.27,28

There are two phase II studies that have studied a response-adapted approach incorporating BV into second-line therapy for rel/ref HL. A multicenter phase II study evaluating BV as a second-line therapy prior to HDT/ASCT demonstrated an ORR of 68% to four cycles of BV alone. PET-negative CR was achieved in 35% of patients, who proceeded directly to HDT/ASCT. In patients who continued to have FDG-avid HL after four cycles of BV, an additional 61% of patients were able to achieve PET-negative CR after treatment with combination chemotherapy (ICE/DICE/IGEV/GND). Overall, 86% of patients were able to proceed to ASCT in the study, and 2-year post-ASCT PFS and OS were 72% and 94%, respectively.29,30 Similarly, Moskowitz and colleagues demonstrated safety and activity of single-agent BV as second-line therapy in 45 patients. PET-negative CR was achieved in 27% after two cycles of BV, and these patients proceeded directly to HDT/ASCT. Patients with PET-positive disease after BV treatment received two cycles of augmented ICE chemotherapy with 69% subsequently achieving CR. Ultimately, 44 of 45 patients who completed treatment were able to undergo ASCT.31

In an attempt to improve response rates to second-line chemotherapy-based salvage regimens, addition of BV to chemotherapy in rel/ref HL has been evaluated in multiple clinical trials. BV plus ESHAP was evaluated in a phase II clinical trial by Garcia-Sanz and colleagues. A total of 66 patients were treated with BV-ESHAP with an observed ORR of 96% and CR of 70%. Overall, 61 patients proceeded to HDT/ASCT and the 1-year post-ASCT PFS was estimated at 87%.32

The addition of BV concurrently with ICE (BV-ICE) chemotherapy was evaluated in 16 patients with relapsed/refractory HL and preliminary results were presented at the 2016 American Society of Hematology (ASH) annual meeting. BV-ICE produced an ORR 94% and CR rate of 88% by investigator assessment and CR 69% by central independent radiographic review. Grade 3–4 myelosuppression was reported in 12% and peripheral neuropathy was seen in 31% of patients. A total of 94% of patients underwent stem cell collection and 75% were able to proceed to ASCT. Median follow up was 6.5 months (range 2–20 months) with three (19%) relapses observed during this time.33

The combination of BV with DHAP as a second-line salvage therapy was evaluated by Hagenbeek and colleagues in a phase 1 dose-escalation trial for rel/ref HL. All 12 patients on the study achieved CR with median follow up of 15.4 months. High rates of grade 3–4 myelosuppression were reported.34

A phase 1/2 study evaluated the combination of BV plus bendamustine as second-line salvage therapy in 53 evaluable patients with rel/ref HL. The combination produced an ORR of 93% with a CR rate of 74%. Patients were not required to proceed to HDT/ASCT after BV plus bendamustine, and the estimated 12-month PFS was 80% for both transplanted patents (n = 40) and the overall study population.35

In addition to BV, inhibitors of the programmed death-1 (PD-1)/PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway are highly effective agents for the treatment of rel/ref HL. The programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) pathway is an immune checkpoint that normally serves to dampen immune responses in tissues. PD-1 is expressed on activated T-cells and binds its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, on tissue cells or antigen presenting cells to decrease T-cell activation, proliferation, and survival.36 Tumor cells can co-opt this pathway to evade attack by the host immune system.36 In particular, the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway appears to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of HL. Frequent genetic alterations of the 9p24.1 region, which includes the PD-L1/PD-L2 loci, are observed in HL cell lines and patient tumor samples, and PD-L1 expression on Reed–Sternberg cells in nearly universal in patients with HL.37

Preliminary results from a phase I/II study of BV in combination with the PD-1 inhibitor, nivolumab, used as second-line treatment in patients with rel/ref HL were presented at the 2016 ASH annual meeting. In the 29 patients who completed four cycles of BV plus nivolumab, the ORR was 90% and the CR rate was 62% with most patients in CR having a Deauville score of 1 or 2. The regimen appeared to be well-tolerated, as few grade 3 or 4 adverse events were observed. Infusion-related reactions (IRRs) were observed in 38% of patients, occurring mainly during the cycle 2 BV infusion, though all but 1 IRR were grade 1 or 2 and there were no discontinuations of either agent due to IRRs or toxicity. Mandatory premedications did not appear to impact the rate or severity of IRRs.38

Chemotherapy-based salvage options for relapse after ASCT

Combination chemotherapy regimens have been studied in patients with HL relapse after HDT/ASCT. Studies of GVD, GemOx and ESHAP all included subgroups of patients with relapse after ASCT, with observed ORRs ranging from 75–90% and CR rates ranging from 17–50%.18,19,22

Bendamustine used as a single agent in patients who have progressed after multiple lines of therapy has produced ORRs of 50–53% and CR rates of 29–33%, though the duration of response is short, with median PFS reported to be 5.7 months but 10.2 months in patients with CR.39 Patients that relapsed within 3 months of ASCT had no response to bendamustine. Grade 3 or higher adverse events included thrombocytopenia (20%), anemia (14%), and infection (14%). Overall, 20% of patients were able to proceed to allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloHCT) after treatment with bendamustine.24,40 Patients who have relapsed after BV may also benefit from bendamustine.41

Other single-agent chemotherapy agents have been studies in rel/ref HL, and include gemcitabine, doxil, vinorelbine, and vinblastine, with observed response rates in the 30–72% range.42–45

Novel agents for salvage of relapsed HL after ASCT

The original pivotal phase II study of BV in patients with rel/ref HL after HDT/ASCT demonstrated an ORR of 75% and CR rate of 34%. Patients who achieved CR had median PFS of 20.5 months.46 Chen and colleagues recently presented long-term outcomes for patients treated with BV after failure of ASCT in relapsed and refractory HL. At 5 years, overall OS was 41% and PFS was 22%. Patients who achieved CR with BV had improved survival with estimated OS and PFS rates of 64% and 52%, respectively. Patients responding to treatment who had a suitable stem cell donor, proceeded to alloHCT. Among patients who achieved CR, 38% continued to be in remission beyond 5 years.47 Of note, retreatment with BV after BV discontinuation has been studied in patients who previously responded to BV producing an ORR of 60%, suggesting that BV can be used as a salvage option in prior BV responders.48

Like BV, PD-1 inhibitors are effective treatment for patients who have failed HDT/ASCT. Ansell and colleagues reported the results of a phase Ib study of nivolumab in heavily pretreated HL patients, demonstrating an ORR of 87%, with a CR rate of 17%.49 At a median follow up of 40 weeks, the rate of PFS at 24 weeks was 86% and median OS has not been reached. A subsequent phase II study of nivolumab in 80 patients who failed ASCT as well as prior BV confirmed a high ORR of 66%, with 9% of patients having a CR per independent review. Notably, the majority of responders remained in remission at the time of censoring, thus a significant proportion of responses appear to be durable.50 A phase Ib study of pembrolizumab in 31 patients with rel/ref HL who failed prior BV demonstrated a 65% ORR with 16% of patients achieving CR.51 A phase II trial (KEYNOTE-087) evaluated safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab in rel/ref HL, including patients who relapsed after BV, ASCT or both, showed an ORR of 69.0% and CR of 22.4%. The study had a low rate of discontinuation and the safety profile was consistent with prior published data.52 Immune-related adverse effects are unique to this group of drugs and include pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis, cutaneous toxicities, endocrinopathies, and inflammation of various other organs. Combination of BV and nivolumab has been evaluated in patients with rel/ref HL after multiple lines of therapy, including ASCT. Diefenbach and colleagues presented preliminary findings at the ASH 2016 annual meeting of 12 patients treated with the combination, reporting that treatment was well-tolerated and effective, including an ORR of 100% and CR rate of 62.5%.53

Other novel treatment options that have been studied in patients who have relapsed after or were refractory to standard therapies include lenalidomide, alone or in combination with bendamustine, everolimus, and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors. Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory agent that has shown activity in relapsed or refractory HL, with an ORR of 19% and CR rate of 3% in the largest study (n = 38) of heavily pretreated HL patients.54 Addition of lenalidomide to bendamustine (Leben combination) showed an ORR of 75% with a CR rate of 44% and median PFS of 11.4 months for those achieving CR/PR versus 3.2 months in patients with stable or progressive disease. Median OS for all patients was 24 months. Overall, patients in CR had a 2-year disease-free survival of 41% (median 14.3 months).55

The HDAC inhibitor, panobinostat, has also been studied for the treatment of rel/ref HL, producing an ORR of 27% and CR rate of 4% with a median PFS of 6.1 months. The estimated 1-year OS was 78%. The most common adverse events were thrombocytopenia, anemia and neutropenia, including grade 3 and 4.56 Similarly, everolimus, an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin, appears to have activity in patients with rel/ref, with an ORR of 47%, though CR is rare and the duration of response is relatively short at 7 months.57

Treatment of elderly patients with rel/ref HL

HL presents a bimodal distribution with a proportion of patients presenting in their sixth decade. A retrospective multicenter study demonstrated a 5-year PFS of 44% and OS of 58% in newly diagnosed patients with HL, with significantly inferior freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) rates than younger patients.58 Limited data on treatment options in rel/ref HL and responses to multidrug chemotherapy exists in patients older than 65 years of age, partly because of exclusion from clinical trials due to comorbidities. Clinical trials with salvage regimens for re/ref HL only rarely included patients above 60 years of age and given the small patient size in this age group per study, survival outcomes are not often reported for elderly patients. There are no guidelines for managing elderly patients in the relapsed setting, and the choice of salvage regimen should be based on patient’s performance status, comorbidities and ability to undergo HDT/ASCT in attempt to achieve remission. If patient is a candidate for HDT/ASCT, the patient should be offered salvage regimen that can lead maximal response, including multidrug chemotherapy irrespective of the patient’s age. In patients who are not candidates for HDT/ASCT, the treatment goal becomes palliative and the choice of therapy is between disease control and the patient’s tolerance of side effects. Regimen options for patients that would not tolerate multiagent chemotherapy include single-agent chemotherapy, BV alone, bendamustine or BV with bendamustine, which included patients over age of 60 years.24,35,40,42,45,46 Novel approaches in treatment in elderly patients with rel/ref HL are necessary.58–60

Role of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in relapsed HL

Prior to development of novel agents, an alloHCT was the only curative option and could still benefit a subgroup of patients in rel/ref HL, such as patients who relapsed after HDT/ASCT or refractory disease to multiple lines of therapy.61 Myeloablative conditioning is associated with decreased OS due to treatment-related mortality (TRM)62; however, reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens allow for decreased rates of TRM in patients undergoing alloHCT, though TRM still remains at around 15–25%. Patients who received alloHCT in CR have a significantly better outcome. Multiple studies have shown PFS and OS of about 30% after RIC.63,64 Patients that have failed multiple lines of therapy, including prior ASCT and BV therapy, but still show sensitive disease to salvage therapy should be considered for alloHCT.

Role of radiation therapy in the salvage setting

Radiation therapy alone (conventional or extended field) as a salvage modality in a relapsed HL can be considered in carefully selected patients that have not received radiation therapy as part of the initial therapy and if there are no adverse risk factors at the time of relapse. Older individuals, who lack constitutional symptoms with only limited stage disease and are not candidates for HDT/ASCT, can be offered radiation therapy as a salvage treatment modality. The GHSG demonstrated a 5-year FFTF of 28% and OS of 51% for second-line radiation therapy for relapsed HL.65 Involved field radiation therapy (IFRT) can be added to second-line chemotherapy, with response rates reported of 88% when treated with ICE and IFRT.14

Conclusions

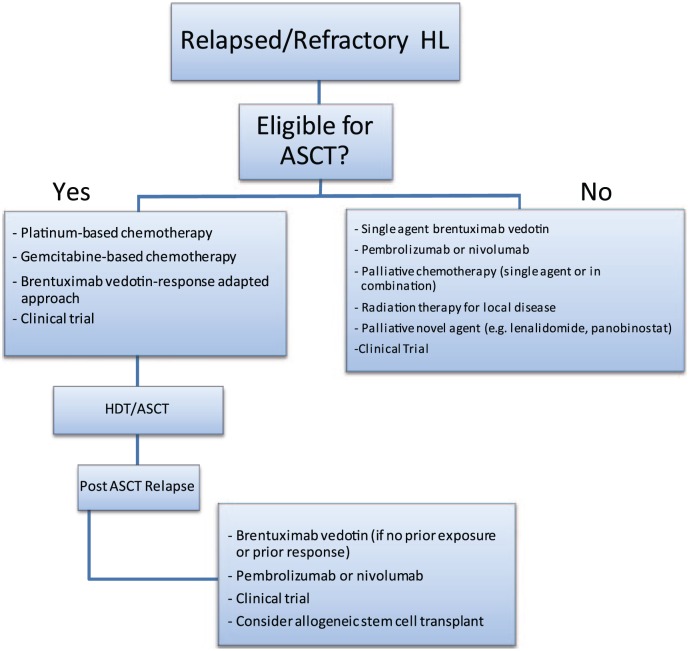

In conclusion, there are abundant salvage therapy options for patients with rel/ref HL (Figure 1). The goal of second-line salvage therapy, chemotherapy-based or with novel agents, is to achieve CR prior to HDT/ASCT, as PET-negative CR is strongly associated with a favorable post-ASCT outcome. The choice of salvage chemotherapy therapy is becoming increasingly difficult in the era of novel agents, as there are no randomized studies to guide the choice of a second-line regimen. At the present time, there is a range of chemotherapy-based and novel-agent-based salvage options that are acceptable for use in the second-line and can lead to excellent ORR and CR rates (Table 1). In the absence of comparative data, platinum-based combination salvage therapy remains the benchmark and standard option as a salvage regimen. However, with introduction of BV into second-line therapy, excellent response rates have been demonstrated, allowing patients to be bridged to ASCT with fewer side effects than conventional chemotherapy. As novel agents move into earlier lines of therapy (BV is currently under study as part of front-line therapy), it may be difficult to interpret data on BV-based second-line regimens in which patients were naïve to BV. Therefore, it will be important to study salvage regimens that incorporate other agents like PD-1 inhibitors, and BV-based salvage regimens in patients with prior BV exposure. In patients who are refractory to pre-ASCT therapy, have failed ASCT, or are ineligible for HDT/ASCT, chemotherapy or novel agents can provide disease control and palliation of symptoms, or can serve as a bridge to alloHSCT. These patients should be considered for enrollment in a clinical trial, as several promising new agents or combinations of novel agents are underway to optimize treatment options for patients with rel/ref HL.

Figure 1.

Relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma treatment algorithm.

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; HDT, high-dose therapy; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Liana Nikolaenko, Department of Hematology and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA, USA.

Robert Chen, Department of Hematology and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1500 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010, USA.

Alex F. Herrera, Department of Hematology and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA, USA

References

- 1. Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, et al. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood 2006; 107: 265–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Santoro A, Bonadonna G, Valagussa P, et al. Long-term results of combined chemotherapy-radiotherapy approach in Hodgkin’s disease: superiority of ABVD plus radiotherapy versus MOPP plus radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1987; 5: 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horning SJ, Hoppe RT, Breslin S, et al. Stanford V and radiotherapy for locally extensive and advanced Hodgkin’s disease: mature results of a prospective clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 630–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gordon LI, Hong F, Fisher RI, et al. Randomized phase III trial of ABVD versus Stanford V with or without radiation therapy in locally extensive and advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: an intergroup study coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (E2496). J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 684–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Radford J, Illidge T, Barrington S. PET-directed therapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Castagna L, Bramanti S, Balzarotti M, et al. Predictive value of early 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) during salvage chemotherapy in relapsing/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) treated with high-dose chemotherapy. Br J Haematol 2009; 145: 369–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adams HJ, Kwee TC. Prognostic value of pretransplant FDG-PET in refractory/relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma treated with autologous stem cell transplantation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hematol 2016; 95: 695–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Devillier R, Coso D, Castagna L, et al. Positron emission tomography response at the time of autologous stem cell transplantation predicts outcome of patients with relapsed and/or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma responding to prior salvage therapy. Haematologica 2012; 97: 1073–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jabbour E, Hosing C, Ayers G, et al. Pretransplant positive positron emission tomography/gallium scans predict poor outcome in patients with recurrent/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer 2007; 109: 2481–2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moskowitz CH, Kewalramani T, Nimer SD, et al. Effectiveness of high dose chemoradiotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with biopsy-proven primary refractory Hodgkin’s disease. Br J Haematol 2004; 124: 645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sirohi B, Cunningham D, Powles R, et al. Long-term outcome of autologous stem-cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2008; 19: 1312–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shah GL, Yahalom J, Matasar MJ, et al. Risk factors predicting outcomes for primary refractory hodgkin lymphoma patients treated with salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol 2016; 175: 440–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moskowitz AJ, Yahalom J, Kewalramani T, et al. Pretransplantation functional imaging predicts outcome following autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2010; 116: 4934–4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moskowitz CH, Nimer SD, Zelenetz AD, et al. A 2-step comprehensive high-dose chemoradiotherapy second-line program for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin disease: analysis by intent to treat and development of a prognostic model. Blood 2001; 97: 616–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hertzberg MS, Crombie C, Benson W, et al. Outpatient-based ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide (ICE) chemotherapy in transplant-eligible patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol 2003; 14(Suppl. 1): i11–i16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Josting A, Rudolph C, Reiser M, et al. Time-intensified dexamethasone/cisplatin/cytarabine: an effective salvage therapy with low toxicity in patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol 2002; 13: 1628–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sasse S, Alram M, Muller H, et al. Prognostic relevance of DHAP dose-density in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma: an analysis of the German Hodgkin-Study Group. Leuk Lymphoma 2016; 57: 1067–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aparicio J, Segura A, Garcera S, et al. ESHAP is an active regimen for relapsing Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol 1999; 10: 593–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bartlett NL, Niedzwiecki D, Johnson JL, et al. Gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (GVD), a salvage regimen in relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma: CALGB 59804. Ann Oncol 2007; 18: 1071–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Santoro A, Magagnoli M, Spina M, et al. Ifosfamide, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine: a new induction regimen for refractory and relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Haematologica 2007; 92: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baetz T, Belch A, Couban S, et al. Gemcitabine, dexamethasone and cisplatin is an active and non-toxic chemotherapy regimen in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s disease: a phase II study by the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Ann Oncol 2003; 14: 1762–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gutierrez A, Rodriguez J, Martinez-Serra J, et al. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatinum: an effective regimen in patients with refractory and relapsing Hodgkin lymphoma. Onco Targets Ther 2014; 7: 2093–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ozdemir E, Aslan A, Turker A, et al. Gemcitabine in Combination with Oxaliplatin (GEMOX) as a salvage regimen in patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood 2015; 126: 1517. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moskowitz AJ, Hamlin PA, Jr, Perales MA, et al. Phase II study of bendamustine in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 456–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Santoro A, Mazza R, Pulsoni A, et al. Bendamustine in combination with gemcitabine and vinorelbine is an effective regimen as induction chemotherapy before autologous stem-cell transplantation for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: final results of a multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 3293–3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Younes A, Bartlett NL, Leonard JP, et al. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) for relapsed CD30-positive lymphomas. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1812–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carson KR, Newsome SD, Kim EJ, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with brentuximab vedotin therapy: a report of 5 cases from the Southern Network on Adverse Reactions (SONAR) project. Cancer 2014; 120: 2464–2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jalan P, Mahajan A, Pandav V, et al. Brentuximab associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2012; 114: 1335–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen R, Palmer JM, Martin P, et al. Results of a multicenter phase II trial of brentuximab vedotin as second-line therapy before autologous transplantation in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015; 21: 2136–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Herrera A, Palmer J, Martin P, et al. Post transplant outcomes in a multicenter phase II study of brentuximab vedotin as first line salvage therapy in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma prior to autologous stem cell transplantation. Haematologica 2016; 101: 47–48. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moskowitz AJ, Schoder H, Yahalom J, et al. PET-adapted sequential salvage therapy with brentuximab vedotin followed by augmented ifosamide, carboplatin, and etoposide for patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a non-randomised, open-label, single-centre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garcia-Sanz R, Sureda A, Gonzalez AP, et al. Brentuximab vedotin plus ESHAP (BRESHAP) is a highly effective combination for inducing remission in refractory and relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma patients prior to autologous stem cell transplant: a trial of the Spanish Group of Lymphoma and Bone Marrow Transplantation (GELTAMO). Blood 2016; 128: 1109. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cassaday RD, Fromm J, Cowan AJ, et al. Safety and activity of brentuximab vedotin (BV) plus ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE) for relapsed/refractory (Rel/Ref) classical hodgkin lymphoma (cHL): initial results of a phase I/II trial. Blood 2016; 128: 1834.27465916 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hagenbeek A, Zijlstra J, Lugtenburg P, et al. Transplant brave: combining brentuximab vedotin with dhap as salvage treatment in relapsed/refractory hodgkin lymphoma. A phase 1 dose-escalation study. Haematologica 2016; 101: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. LaCasce AS, Bociek G, Sawas A, et al. Brentuximab vedotin plus bendamustine: a highly active salvage treatment regimen for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2015; 126: 3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12: 252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Green MR, Monti S, Rodig SJ, et al. Integrative analysis reveals selective 9p24.1 amplification, increased PD-1 ligand expression, and further induction via JAK2 in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2010; 116: 3268–3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Herrera AF, Bartlett NL, Ramchandren R, et al. Preliminary results from a phase 1/2 study of brentuximab vedotin in combination with nivolumab in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2016; 128: 1105. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ghesquieres H, Stamatoullas A, Casasnovas O, et al. Clinical experience of bendamustine in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of the French compassionate use program in 28 patients. Leuk Lymphoma 2013; 54: 2399–2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Corazzelli G, Angrilli F, D’Arco A, et al. Efficacy and safety of bendamustine for the treatment of patients with recurring Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2013; 160: 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zinzani PL, Derenzini E, Pellegrini C, et al. Bendamustine efficacy in Hodgkin lymphoma patients relapsed/refractory to brentuximab vedotin. Br J Haematol 2013; 163: 681–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Clozel T, Deau B, Benet C, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin: an efficient treatment in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma relapsing after high dose therapy and stem cell transplation. Br J Haematol 2013; 162: 846–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Devizzi L, Santoro A, Bonfante V, et al. Vinorelbine: an active drug for the management of patients with heavily pretreated Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol 1994; 5: 817–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Little R, Wittes RE, Longo DL, et al. Vinblastine for recurrent Hodgkin’s disease following autologous bone marrow transplant. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 584–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Venkatesh H, Di Bella N, Flynn TP, et al. Results of a phase II multicenter trial of single-agent gemcitabine in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy-refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma 2004; 5: 110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 2183–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen R, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Five-year survival and durability results of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2016; 128: 1562–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bartlett NL, Chen R, Fanale MA, et al. Retreatment with brentuximab vedotin in patients with CD30-positive hematologic malignancies. J Hematol Oncol 2014; 7: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 311–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Younes A, Santoro A, Shipp M, et al. Nivolumab for classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma after failure of both autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab vedotin: a multicentre, multicohort, single-arm phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 1283–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Armand P, Shipp MA, Ribrag V, et al. Programmed death-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma after brentuximab vedotin failure. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 3733–3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen R, Zinzani PL, Fanale MA, et al. Phase II study of the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab for relapsed/refractory classic Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 2125–2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Diefenbach CS, Hong F, David KA, et al. A phase I study with an expansion cohort of the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab and brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: a trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E4412 Arms D and E). Blood 2016; 128: 1106. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fehniger TA, Larson S, Trinkaus K, et al. A phase 2 multicenter study of lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2011; 118: 5119–5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pinto A, Pavone V, Angrilli F, et al. Lenalidomide in combination with bendamustine for patients with chemorefractory Hodgkin lymphoma: final results of the Leben multicenter phase 1/2 study. Blood 2015; 126: 1541. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Younes A, Sureda A, Ben-Yehuda D, et al. Panobinostat in patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma after autologous stem-cell transplantation: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 2197–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Johnston PB, Inwards DJ, Colgan JP, et al. A phase II trial of the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Hematol 2010; 85: 320–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Evens AM, Helenowski I, Ramsdale E, et al. A retrospective multicenter analysis of elderly Hodgkin lymphoma: outcomes and prognostic factors in the modern era. Blood 2012; 119: 692–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bjorkholm M, Svedmyr E, Sjoberg J. How we treat elderly patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol 2011; 23: 421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stark GL, Wood KM, Jack F, et al. Hodgkin’s disease in the elderly: a population-based study. Br J Haematol 2002; 119: 432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Castagna L, Sarina B, Todisco E, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation compared with chemotherapy for poor-risk Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009; 15: 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sureda A, Robinson S, Canals C, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning compared with conventional allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an analysis from the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Alvarez I, Sureda A, Caballero MD, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation is an effective therapy for refractory or relapsed hodgkin lymphoma: results of a spanish prospective cooperative protocol. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006; 12: 172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sureda A, Pereira MI, Dreger P. The role of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the treatment of relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol 2012; 24: 727–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Josting A, Nogova L, Franklin J, et al. Salvage radiotherapy in patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a retrospective analysis from the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 1522–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]