Abstract

Objective

To examine the (a) prevalence of and (b) association between alcohol, risky sex, and HIV among Russians at-risk for primary or secondary HIV transmission.

Method

Electronic databases were searched to locate studies that sampled Russians, assessed alcohol, and included either a behavioral measure of risk or a biological measure of HIV. Weighted mean (logit) effect sizes were calculated using random-effects assumptions. Moderator analyses were conducted using meta-regression.

Results

Studies (19) sampled 12,916 Russians (Mage = 29; 36% women). Participants were recruited from clinical (52%; e.g., STI clinic, drug treatment), other high-risk community settings (32%; e.g., sexual/drug networks), or both (16%). Findings indicate that a substantial proportion of the participants used alcohol (77%; 55% heavy drinking). One-half of participants reported using condoms (52%) but only 29% used condoms consistently. Most participants reported drinking before sex (64%). Of the studies testing for HIV, 10% of participants tested positive. Meta-regression analyses indicated that hazardous/harmful alcohol use was associated with increased risky behaviors (i.e., multiple partners, inconsistent condom use).

Conclusions

These findings support the need for and potential benefit of addressing alcohol use in HIV prevention programming in Russia.

Keywords: alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, HIV, Russia, meta-analysis

Introduction

Russia has one of the fastest growing HIV epidemics in the world. More than half (69%) of the people living with HIV across Eastern Europe and Central Asia live in Russia, where new infections are rapidly increasing and now account for 80% of all new HIV infections in the region [1]. Due to the country’s slow response to the HIV epidemic, Russia now faces a growing HIV epidemic with low treatment coverage and a substantial disease burden [2].

Transmission of HIV is a growing public health concern in Russia. While transmission of HIV in Russia was initially concentrated among injection drug users (IDUs), the incidence of HIV among IDUs has stabilized. In contrast, HIV incidence has increased in all other population groups primarily through heterosexual contact. The proportion of new HIV infections attributed to sexual transmission has increased from 4% in 2001 to 36% in 2009 [3], and this trend has been observed in both urban and rural settings [4, 5]. Given that the incidence of HIV in the country is higher than those of western European countries, and the stabilization of HIV among IDUs, continued growth in the sexual transmission of HIV is of great concern [6].

Alcohol Use among Russians

Russia has one of the highest rates of alcohol consumption per capita in the world [7]. Alcohol use has contributed to declines in life expectancy and to the socio-economic disparities in Russian mortality [8]. The adverse effects of drinking in Russia are well documented. The Russian Federation has the highest percentage of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) attributable to alcohol [9], and Russians have the highest alcohol-attributable deaths as a percentage of total deaths [7, 10]. Alcohol consumption is a major health concern because it is associated with the sexual transmission of HIV.

Alcohol Use and Sexual Risk

The association between alcohol and sexual risk behaviors has been demonstrated among a variety of populations [11–15]. Alcohol is associated with HIV transmission through behavioral as well as physiological effects of ethanol [16]. Behaviorally, alcohol use leads to disinhibition and diminished perception of risk, increasing the likelihood that individuals put themselves at risk of HIV infection by engaging in unsafe sexual practices (i.e., multiple sex partners, unprotected sexual intercourse, concurrent sexual partners) [17]. Problematic alcohol use is associated with increased risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs), which increases the likelihood of both transmitting and acquiring HIV [18–20]. Physiologically, among people living with HIV, alcohol misuse promotes transmission by increased inflammation and is associated with higher levels of viral replication and accelerated disease progression [21].

The Current Study

Alcohol use in the context of sexual risk behaviors has the potential to exacerbate the HIV epidemic in Russia. Identifying populations at risk for primary or secondary HIV transmission is of great public health importance, as a step towards developing prevention interventions to reduce HIV/STIs risk behaviors in populations vulnerable to HIV infection. Therefore, the purposes of this systematic review and meta-analysis were (1) to examine the prevalence of (a) alcohol use, (b) sexual risk behaviors, and (c) HIV/STIs among Russians, and (2) to examine potential predictors of alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV/STIs incidence. We limited our review to studies in high-risk settings (e.g., HIV/STI clinics, drug networks) because (a) few studies sampled Russians in the general population and (b) participants recruited from these settings were most at risk for primary or secondary transmission of HIV [22].

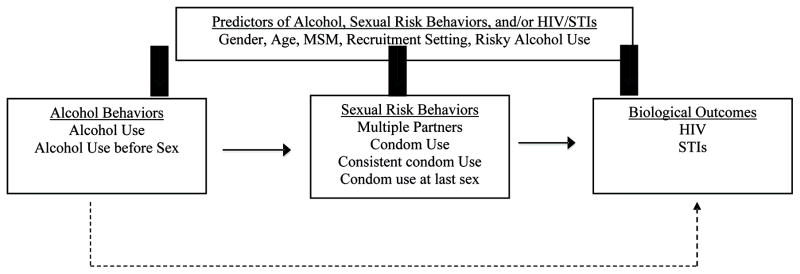

We examine the extent to which participant characteristics moderated the relation between behavioral and biological outcomes. Based on the literature, we developed a conceptual model to guide our analyses and generate testable hypotheses (Figure 1). We hypothesized that current alcohol use would predict sexual risk behaviors and subsequent outcomes (i.e., HIV and other STIs). Thus, for example, we expected that participants who drank alcohol would report greater sexual risk behaviors (e.g., multiple sexual partners, inconsistent condom use) compared to those who abstained. Based on previous literature, we hypothesized that participants’ gender would predict alcohol use, with greater proportions of men reporting alcohol use or heavy alcohol use compared to women [23]. In addition, young people and certain groups of people are highly vulnerable to HIV infection, such as men who have sex with men (MSM) and STI clinic patients [24–26]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the prevalence of alcohol consumption, sexual risk behavior, and HIV/STIs would be greater among studies sampling participants who were of younger age, MSM, or patients attending an STI clinic (vs. patients recruited from other settings). This study contributes to the literature examining the association between alcohol and risky sex, identifies vulnerable populations to HIV, and provides recommendations for HIV prevention in Russia.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Alcohol Use, Sexual Risk Behaviors, and HIV

METHODS

This meta-analysis was conducted to satisfy the standards implied in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [27]. The PRISMA checklist can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Search Strategy

Several strategies were used to obtain studies meeting our inclusion criteria. First, studies were retrieved from electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, The Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Web of Science, Global Health, Dissertation Abstracts, CORK, ERIC, EMBASE, and SoclINDEX) using a Boolean search strategy with no date limits. The searches consisted of the following broad terms: alcohol, sex, and Russia. Search terms were modified using individual database search guidelines, as needed, for each electronic database searched. For example, the search terms used in our PubMed search were as follows: (binge drinking OR (binge AND (alcohol OR ethanol)) OR alcohol drinking OR alcohol abuse OR alcoholic OR alcohol OR “alcohol-related disorders”[MeSH] OR alcoholism OR intoxicat* OR drunk*) AND (“sexually transmitted diseases”[Mesh] OR “sexually transmitted”[tiab] OR STI OR STD OR AIDS[sb] OR condom OR unsafe sex OR sexual behavior OR (risk OR risk taking OR risk factor*) AND (sex OR sexu* OR sexual behavior)) AND (Russia or “Russian Federation” or Russian). Second, reference sections of relevant manuscripts (including published reviews obtained through the electronic reference databases search) and included studies were reviewed. Finally, unpublished papers (e.g., dissertations or conference reports) were sought through electronic databases or requests from authors. No date or language restrictions were applied.

Inclusion Criteria

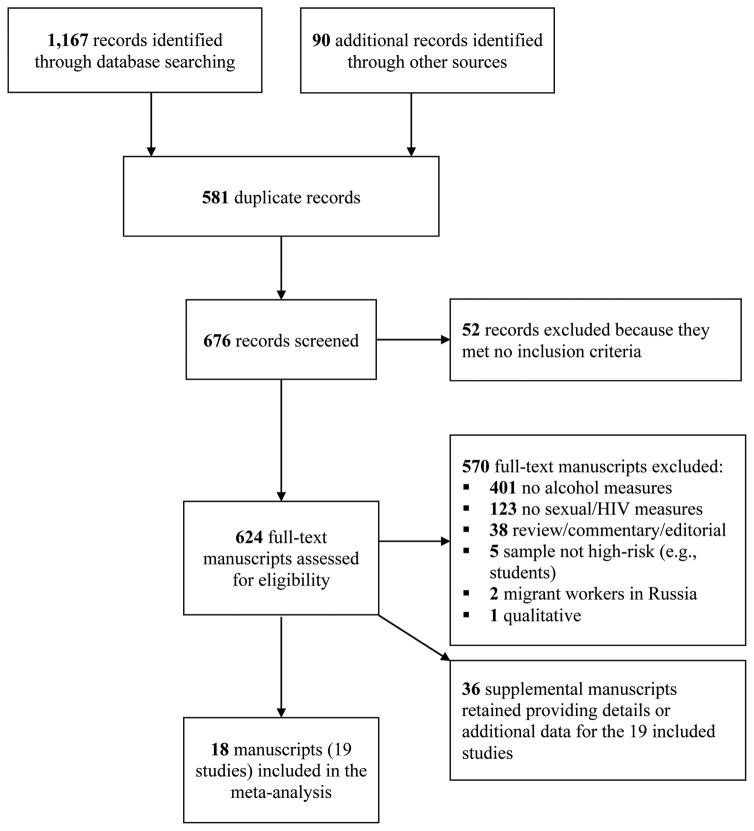

Studies were included if they (a) sampled people living in Russia and (b) assessed both alcohol and behavioral measure of risk (e.g., condom use, multiple sex partners) or a biological measure of HIV, and (c) provided sufficient information needed to calculate effect sizes. Comprehensive electronic searches identified 1,167 potentially relevant records and an additional 90 records were identified through other sources. After removing duplicates, 676 records were screened for possible inclusion. Of these, 52 were excluded based on their titles and abstracts because they did not meet inclusion criteria. Of the 624 full-text articles screened for eligibility, 570 were excluded. When authors reported details and/or outcomes of the same sample in multiple studies, the studies were linked in the database to be represented as a single study and the manuscript reporting the main study outcomes was selected as the primary study. Primary studies (and linked papers) that fulfilled selection criteria and were available through December 2014 were included. Nineteen studies reported in 18 manuscripts (plus 36 supplemental manuscripts providing further study and sample details) were included in the final analyses (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of the Study Selection Process for the Meta-Analysis

Coding and Reliability

Two independent coders (CWL and LAJSS) extracted study information, design and measurement (e.g., recruitment method, method of assessments), sample characteristics (e.g., gender, marital status). If data from the same sample appeared in multiple manuscripts, the most comprehensive report was used while supplementing missing data from the other report(s). Methodological study quality of the individual studies was assessed using 17 items from validated measures [28–30]. The number of methodological quality items assessed for each study depended on study design: (a) cross-sectional studies were assessed using seven items, (b) cohort studies were assessed using 11 items, and (c) all 17 items applied to intervention studies. The proportion of methodological quality criteria met for each study design was used in the analyses. Examples of methodological quality items examined include: (a) study hypothesis/aim/objective well-defined; (b) participants of the study representative of the population from which they were recruited; (c) adequate selection criteria; (d) appropriate measurements of outcome studied; (e) blinding of outcome assessors; (f) valid statistical analysis; (g) characteristics of participants who withdrew were described. Inter-rater agreement was calculated separately for categorical and continuous variables. For the categorical variables, raters agreed on an average of 81% of the judgments (mean kappa = 0.65). The mean intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.90 for all continuous variables, indicating strong agreement. Disagreements were resolved and consensus was reached through discussion.

Study Outcomes and Effect Sizes

Effect sizes (ES) were calculated for behavioral and biological variables available in the manuscripts reporting data from the 19 studies. Behavioral variables included current alcohol use, heavy drinking, alcohol abuse/dependence, alcohol use prior to sex, multiple sexual partners, condom use, condom use at last sexual intercourse, and consistent condom use. Biological variables included diagnosis of HIV and other STIs. Only the baseline data were included from studies reporting repeated measures over time: one longitudinal cohort study [31] and four intervention studies [32–35].

ES were calculated by dividing the number of participants who reported, or were diagnosed with, a specific behavioral (e.g., alcohol or condom use) or biological (e.g., HIV) outcome by the total number of participants in the sample. Consistent with standard meta-analytic methods [36], the ES (proportions) were converted to logits and used in all analyses. Results from the analyses (using logits) were then converted back into proportions (along with corresponding confidence intervals) for ease of interpretation.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the weighted mean (logit) ES for behavioral and biological outcomes using random effects procedures [36]. All analyses were conducted with Stata 12 [37]. Weighted mean (logit) ESs (prevalence estimates) were calculated using random-effects procedures (estimating the additive [between studies] component of variance using full information maximum likelihood). The 95% confidence intervals (CI) surrounding a weighted mean (logit) ES were calculated; CIs indicate the degrees of precision as well as the significance of the mean (logit) effect size [36]. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Q statistic which is approximately distributed as a chi-square statistic with k (number of effect sizes) minus 1 degrees of freedom [36]. To assess the proportion of variation across studies due to heterogeneity, I2 and its corresponding 95% CIs were calculated [38]. I2 varies between 0 and 100% with higher values indicating considerable heterogeneity.

To explain variability in the prevalence estimates of alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, as well as HIV and STIs, analyses were conducted using both meta-regression and an analog to the ANOVA following random-effects assumptions [36]. Sample characteristics (e.g., mean age, proportion women, MSM, and STI clinic patients) and risk characteristics (e.g., proportion using alcohol, hazardous/harmful alcohol use, multiple sexual partners, and condom use) were examined as predictors of the prevalence estimates for behavioral and biological outcomes. The list of predictors was selected based on a literature review of relevant studies (see Figure 1). Analyses were conducted only for outcomes with at least five studies. Severity of alcohol use was dichotomized into those engaging in hazardous/harmful alcohol use (assigned a value of one; defined as the majority of the study sample meeting criteria for alcohol abuse/dependence, or reaching hazardous/harmful thresholds on standardized validated measures such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, [39]) and regular alcohol use (assigned a value of zero). Hazardous/harmful alcohol use was tested as a predictor along with other variables in the analyses. (The list of continuous variables used as predictors of alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV/STIs appears in Table 2.)

Table 2.

Prevalence estimates (proportion) of alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV/STIs among Russians in High-Risk Settings

| Outcome | k | Prevalence Estimate % (95% CI) | Q | I2 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Use and Misuse† | ||||

| Current alcohol use | 13 | 77% (47, 92) | 976.61 | 99 (98, 99) |

| Heavy drinking | 4 | 55% (16, 88) | 127.43 | 98 (96, 99) |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 3 | 58% (49, 67) | 15.70 | 87 (64, 96) |

| Alcohol use prior to sex | 5 | 64% (23, 91) | 150.36 | 97 (96, 98) |

| Sexual Risk Behaviors† | ||||

| Multiple sexual partners‡ | 12 | 40% (20, 64) | 410.84 | 97 (96, 98) |

| Condom use | 6 | 52% (20, 82) | 246.13 | 98 (97, 99) |

| Condom use at last sex event | 3 | 57% (14, 92) | 35.43 | 94 (87, 98) |

| Consistent condom use | 11 | 29% (12, 54) | 469.84 | 98 (97, 98) |

| HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections | ||||

| HIV+, diagnosed | 9 | 10% (2, 34) | 710.86 | 99 (99, 99) |

| STI, diagnosed | 4 | 13% (2, 59) | 19.90 | 85 (63, 94) |

| STI, self-reported | 6 | 36% (12, 69) | 12.40 | 60 (1, 84) |

Note. Prevalence values were estimated under random-effects assumptions (full information maximum likelihood).

Alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors include behaviors reported within the past 12 months or less unless otherwise indicated (e.g., last sex event).

RESULTS

Study Characteristics

Table 1 provides details for the 19 studies included in the review. The studies were published in journals between 2004 and 2015, and their data were collected between 1997 and 2011. Most of the studies used an observational study design (74% cross-sectional; 5% longitudinal); 21% used an intervention study design. Study participants were recruited via clinical contact (53%; e.g., STI clinic, drug treatment); 32% recruited participants from high-risk community settings (e.g., drug networks); or both clinical and high-risk community settings (16%). The proportion of methodological quality (MQ) criteria met ranged from 50% to 88% (M = 72%, SD = 10%) indicating moderate to strong methodological quality of the studies (cross-sectional studies: M = 69%, SD = 9%, k = 14; intervention studies: M = 82%, SD = 5%, k = 4; longitudinal cohort: M = 71%, k = 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 19 Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis

| Study | Recruitment and Location | Sample | Alcohol Use | Sexual Risk Behaviors | HIV/STIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdala [32]† | Patients at a public STI clinic in St. Petersburg | N = 307 (87%); 28% F; mean age = 27; 4% CSW | 82% ABS 73% PDA |

72% MSP 76% CDM 40% CDM (last) 11% CC |

36% STI (SR) |

| Amirkhanian [48]† | MSM recruited from community venues in St. Petersburg | N = 38 (100%); 0% F; mean age = 28; 100% MSM | 96% ALC | 68% MSP 47% CDM |

5% HIV+ 11% STI (D) |

| Baral [31] | CSWs recruited via advertisements and direct contact by outreach workers from saunas frequented by male sex workers in Moscow | N = 50 (84%); 0% F; mean age = 23; 100% MSM; 100% CSW | 92% ALC 70% ABS with clients |

100% MSP 62% CC |

16% HIV+ 24% STI (D) |

| Eritsyan [49]† | Study 1. IDUs recruited by outreach workers from clinical (e.g., narcology treatment) and community (e.g., HIV advocacy service) sources in Ivanovo and Novosibirsk | N = 593 (100%); 28% F; mean age = 25 | 85% ALC 25% PBD |

14% MSP 22% CC |

19% HIV+ |

| Study 2. Non-IDU sexual partners in Ivanovo and Novosibirsk | N = 82 (100%); 83% F; mean age = 25 | 100% ALC | 9% MSP 31% CC |

7% HIV+ | |

| Fleming [50] | Patients receiving treatment for TB at one of two TB hospitals in St. Petersburg or Ivanovo | N = 200 (100%); 28% F; mean age = 42 | 63% AA/D 45% HED |

NR | <1% HIV+ |

| Hoffman [33]† | IDUs recruited from needle exchange sites and other venues; chain referral for social network members (IDU and non-IDU) in St. Petersburg | N = 432 (100%); 34% F; median age = 29interv, 28control; 53% CSW | 63% ALC | 17% CC | 43% HIV+ |

| Iguchi [51]† | IDUs and MSM recruited using respondent-driven sampling in St. Petersburg | N = 921 (100%); 24% F; mean age = 28;19% MSM | 83% ALC 40% HED 66% PDB |

41% MSP 61% CDM (last) |

14% HIV+ 7% STI (D) |

| Krupitsky [52]† | Patients receiving care at the Leningrad Regional Center of Addictions | N = 8,056 (100%); 11% F; mean age = 36 | 69% AA/D | NR | 5% HIV+ |

| Krupitsky [53] | Patients receiving HIV treatment at an infectious disease hospital in St. Petersburg | N = 201 (100%); 38% F; mean age = 27 | 48% AA/D | 51% MSP 11% CC |

100% HIV+ 93% STI (D) |

| Niccolai [54] | Male clients of CSW recruited via referrals from CSW, peers, and STI clinicians and via street outreach | N = 62 (100%); 0% F; mean age = 35; 0% CSW | 92% ALC 48% ABS at last sex with CSW |

70% CDM (last) 54% CC |

74% HIV tested 2% HIV+ (SR) 29% STI (SR) |

| Odinokova [55] | CSW recruited by street outreach work in locations (e.g., brothels, hotels) where CSWs frequent in St. Petersburg and Orenburg | N = 896 (100%); 100% F; 61% ≥25 years; 0% MSM; 100% CSW | 30% ALC 69% HED |

100% MSP | 39% STI (SR) |

| Samet [34]† | Patients with alcohol and/or drug dependence recruited from one of two narcology hospitals in St. Petersburg | N = 181 (90%); 25% F; mean age = 33 | 72% ALC 64% HED 60% AA/D |

70% MSP 55% CDM 4% CC |

15% HIV+ 43% STI (SR) |

| Samet [35]† | HIV+ heavy drinkers from clinical (HIV/AIDS clinic, drug treatment) and non-clinical (needle exchange program) sites in St. Petersburg | N = 700 (75%); 41% F; mean age = 30; 2% MSM | 100% ALC 81% HED 41% ABS 64% AA/D |

27% MSP 24% CC |

100% HIV+ 15% STI (D) 41% STI (SR) |

| Shipitsyna [56] | Sexually active youth receiving STI treatment at one of three youth health clinics in St. Petersburg | N = 432 (100%); 70% F; mean age = 21; <1% MSM | 29% ALC | 30% MSP 50% CC |

17% STI (D) 39% STI (SR) |

| Vasquez [57] | Patients receiving care at HIV clinics in St. Petersburg | N = 152 (100%); 52% F; mean age = 32 | 52% ALC | 60% CDM | 100% HIV+ 29% STI (SR) |

| Zhan [58]† | Patients at one of two STI clinics in St. Petersburg | N = 799 (100%); 33% F; mean age = 27; 4% MSM; 0% CSW | 37% ALC | 39% MSP 24% CDM |

55% HIV− 25% STI (D) 18% STI (SR) |

| Zhan [59]† | Patients at an STI clinic in St. Petersburg | N = 440 (100%); 35% F; mean age = 28; <1% MSM | 85% ALC 26% ABS with steady 76% ABS with casual 47% PDC |

38% MSP 49% CDM 74% CC |

97% HIV− (SR) 11% STI (SR) |

| Zhan [60]† | Patients at an STI clinic in St. Petersburg | N = 502 (100%); 60% F; mean age = 27; 0% MSM | 17% PDA | 41% MSP (lifetime) | <4% HIV+ (SR) 100% STD (SR) |

Note. MSM, men who have sex with men; CSW, commercial sex worker; TB, tuberculosis; N (%), number who consented to the study (proportion retention); F, proportion female; ALC, alcohol use; STI (SR), sexually transmitted infection (self-reported); STI (D), sexually transmitted infection (diagnosed); HED, heavy (episodic) drinking; AA/D, alcohol abuse/dependence; ABS, alcohol use before sex; PBA, problem drinking (as defined by AUDIT score ≥ 8); PBB, problem drinking (defined as ≥3 for men and ≥2 for women on AUDIT-C); PBC, problem drinking (defined as ≥4 for men and ≥3 for women on AUDIT-C); PBD, problem drinking (≥ 2 on CAGE); MSP, multiple sexual partners; CDM, condom use; CC, consistent condom use; NR, not reported.

Details of the study were obtained from the primary paper and linked papers (see Supplementary Material 2).

Of the 12,916 participants sampled, 36% were women and 64% were men; mean age was 29 years (range = 21 to 42, SD = 5). Table 2 provides the prevalence estimates of alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV/STIs among people living in Russia in high-risk settings. The prevalence of current alcohol use was 77% (95% CI: 47, 92, k = 13). Heavy drinking in past month was reported in 55% (95% CI: 16, 88, k = 4), and 58% (95% CI: 49, 67, k = 3) reported alcohol abuse/dependence. Alcohol use prior to sex was reported in 64% (95% CI: 23, 91, k = 5). Many participants, 40% (95% CI: 20, 64, k = 12), reported having multiple sexual partners. Condom used was reported by 52% (95% CI: 20, 82, k = 6), condom use at last sexual event was reported by 57% (95% CI: 14, 92, k = 3), and consistent condom use was reported by 29% (95% CI: 12, 54, k = 11). STIs were diagnosed in 13% of participants (95% CI: 2, 59, k = 4), 10% tested positive for HIV (95% CI: 2, 34, k = 9), and 36% of participants self-reported a current or prior STI, excluding HIV (95% CI: 12, 69, k = 6).

Predictors of Alcohol Use, Sexual Risk Behaviors, and HIV/STIs

Bivariate regression analyses were conducted to examine whether a priori determined sample characteristics related to the variability in prevalence estimates (for continuous variables, see Table 3; categorical variables are not tabled).1

Table 3.

Results from the Meta-Regression Analyses

| Outcomes | B (SE) | p | k | I2 residual |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Use and Misuse | ||||

| Alcohol use | ||||

| mean age | 0.04 (0.11) | 0.736 | 11 | 99 |

| % women | −2.44 (1.23) | 0.074 | 13 | 98 |

| % MSM | 2.43 (1.22) | 0.094 | 8 | 99 |

| Alcohol use prior to sex | ||||

| mean age | −0.13 (0.09) | 0.231 | 5 | 96 |

| % women | −0.47 (2.51) | 0.864 | 5 | 98 |

| % MSM | 0.65 (0.99) | 0.577 | 4 | 94 |

| Sexual Risk Behaviors | ||||

| Multiple sexual partners | ||||

| mean age | 0.16 (0.09) | 0.112 | 12 | 97 |

| % women | −3.18 (1.16) | 0.021 | 12 | 97 |

| % MSM | 1.39 (0.46) | 0.029 | 7 | 87 |

| % using alcohol (current) | −0.48 (1.37) | 0.735 | 10 | 97 |

| % using alcohol before sex | 3.42 (2.03) | 0.233 | 4 | 97 |

| Condom use | ||||

| mean age | 0.06 (0.14) | 0.719 | 6 | 98 |

| % women | 0.36 (2.30) | 0.884 | 6 | 98 |

| % MSM | 0.49 (1.03) | 0.718 | 3 | 96 |

| % using alcohol (current) | 1.26 (1.32) | 0.410 | 5 | 94 |

| % using alcohol before sex | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Consistent condom use | ||||

| mean age | −0.07 (0.11) | 0.522 | 10 | 98 |

| % women | −0.34 (1.79) | 0.852 | 11 | 98 |

| % MSM | 0.38 (1.23) | 0.778 | 5 | 99 |

| % using alcohol (current) | 0.44 (2.16) | 0.845 | 9 | 98 |

| % using alcohol before sex | 0.24 (4.24) | 0.959 | 5 | 99 |

| HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections | ||||

| HIV+ diagnosis | ||||

| mean age | −0.11 (0.05) | 0.067 | 8 | 80 |

| % women | 0.18 (1.96) | 0.927 | 9 | 97 |

| % MSM | −0.40 (1.09) | 0.774 | 3 | 55 |

| % using alcohol (current) | −5.10 (1.54) | 0.021 | 7 | 83 |

| % using alcohol before sex | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| % multiple sexual partners | −0.02 (0.64) | 0.975 | 6 | 64 |

| % condom use | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| % consistent condom use | −0.91 (2.16) | 0.702 | 5 | 97 |

| STI, self-reported | ||||

| mean age | −0.01 (0.05) | 0.791 | 5 | 75 |

| % women | 0.16 (0.34) | 0.655 | 6 | 67 |

| % MSM | 10.14 (16.43) | 0.648 | 3 | 61 |

| % using alcohol (current) | 0.07 (0.53) | 0.909 | 5 | 72 |

| % using alcohol before sex | −0.16 (1.04) | 0.905 | 3 | 67 |

| % multiple sexual partners | −0.10 (0.20) | 0.672 | 4 | 30 |

| % condom use | −0.62 (2.63) | 0.854 | 3 | 84 |

| % consistent condom use | −0.83 (0.73) | 0.374 | 4 | 63 |

Note. For each outcome, moderators are evaluated on a bivariate basis, with the unstandardized estimates (B) provided. Moderators in boldface are statistically significant (ps <0.05).

Alcohol use and misuse

Sample characteristics (e.g., age, gender, MSM) were not associated with current alcohol use or alcohol use before sex with one exception. The prevalence of alcohol use before sex was higher in studies that sampled patients from STI clinics (79%, 95% CI = 70, 86, k = 2) compared to those studies that sampled from other settings (49%, 95% CI = 39, 59, k = 3), QB (1) = 18.26, p <.001.

Sexual risk behaviors

The prevalence of multiple sexual partners was higher when studies sampled fewer women (B = −3.18, p <.02, k = 12) and more MSM (B = 1.39, p <.05, k = 7). Hazardous/harmful alcohol use predicted the prevalence of multiple sexual partners such that hazardous/harmful users reported more sexual partners (53%, 95% CI = 48, 81, k = 7) than regular alcohol users (32%, 95% CI = 48, 81, k = 5), QB (1) = 3.86, p = .050. Consistent condom use was less prevalent among hazardous/harmful drinkers (11%, 95% CI = 4, 29, k = 4) vs. regular drinkers (44%, 95% CI = 4, 29, k = 7), QB (1) = 7.72, p = .005.

HIV and other sexually transmitted infections

The rates of HIV were lower when the studies sampled more current alcohol users (B = −5.10, p <.02, k = 7). No study or risk characteristic was significantly associated with STIs (diagnosed or self-reported).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the prevalence of alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV/STIs among Russians sampled from high-risk settings. We integrated the results of 19 studies involving 12,916 participants living in Russia, sampled between 1997 and 2011. The results indicated that 10% and 13% tested positive for HIV and other STIs, respectively. Thus, our study samples were at high-risk for HIV relative to the general population of Russia (0.6% adult HIV prevalence; UNAIDS, 2014). Furthermore, our findings showed that the prevalence of sexual risk behaviors (e.g., having multiple sex partners, alcohol use prior to sex) was high, while the proportion reporting protective behavior (i.e., consistent condom use) was low. Moreover, heavy drinking (55%) and alcohol abuse/dependence (58%) were substantially higher when compared to national data (heavy drinking, 19%; alcohol abuse, 17%; alcohol dependence, 9%) [7]. Thus, our findings highlighted the high rates of alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV in Russia.

Our analyses showed that the incidence of HIV was negatively associated with the proportion of the sample currently using alcohol. Further inspection of this unexpected finding indicated that the finding was largely driven by a single study [33] that, in contrast with the other studies, reported lower rates of alcohol use (63% vs. 72 – 100%) and higher incidence of HIV (43% vs. 5 – 19%). Alcohol use did not remain a significant predictor of a positive HIV diagnosis after removing the outlier (B = −2.38, p = .28, k = 6). Another possible explanation for this unexpected finding was that examining current drinking might not capture the factors that drive HIV transmission in this population given that alcohol use (and misuse) is a socially acceptable behavior in Russia. Because general alcohol consumption does not indicate risk, we further explored alcohol risk behaviors by classifying the samples as hazardous/harmful or regular drinkers. Hazardous/harmful drinking was not associated the prevalence of HIV, or other STIs (self-reported or diagnosed). These findings suggested that alcohol use may not be directly linked to HIV/STIs but may be indirectly related through increased sexual risk behaviors [17].

Previous studies examining the association between alcohol and risky sex showed that global drinking behaviors were correlated with more sexual risk behaviors [17]. The findings from our regression analyses indicated that any alcohol use or alcohol before sex was not associated with sexual risk behavior but hazardous/harmful drinking was significantly associated with the prevalence of sexual partners and condom use. Hazardous/harmful drinkers were nearly twice as likely to have had multiple sexual partners as compared to regular drinkers (53% vs. 32%). Compared to regular drinkers, hazardous/harmful drinkers were four times less likely to report consistent condom use (11% vs. 44%). Our findings were consistent with recent research showing that the odds of having multiple sexual partners and engaging in inconsistent condom use were higher for hazardous/harmful drinkers relative to abstinent/low-level drinkers living in Russia [40]. Reducing hazardous/harmful alcohol use may be a key consideration in reducing sexual transmission of HIV among Russians.

Prior research showed that patients attending STI clinics engaged in poor health behaviors (e.g., alcohol use) that facilitated the acquisition of STIs, including HIV [41, 42]. Our meta-regression analyses showed that STI clinic patients (vs. participants recruited from other settings) were more likely to report alcohol use and consuming alcohol prior to sex. We did not find any differences between STI clinic patients and participants recruited from other settings on the prevalence of multiple sexual partners, condom use, or HIV/STIs. This unexpected finding was likely an artifact of the sample selection (i.e., studies sampling participants at high-risk for HIV) rather than the absence of sexual risk behavior and/or STIs among clinic patients. Thus, reducing risky alcohol use among STI clinic patients may be important intervention target area in Russia.

To our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to examine the prevalence of alcohol and sexual risk behaviors related to HIV among people recruited from high-risk settings in Russia. By documenting the prevalence of alcohol use and risky sex, meta-analysis provides an empirical foundation for the development of HIV risk reduction interventions as well as recommendations for primary-level research. The results support the potential benefits of delivering sexual risk reduction interventions to alcohol abusing populations. The results of our meta-regression analyses imply that hazardous/harmful alcohol use, and not general alcohol use, is associated with the prevalence of sexual risk behaviors with high-risk populations. Although these analyses do not establish a causal link between alcohol and sexual risk behavior, our findings provide support for the view that hazardous/harmful alcohol use may be an important risk factor for HIV transmission via risky sexual behavior [17].

Limitations

The study findings need to be understood in light of limitations. First, the behavioral outcomes were self-reported, which were vulnerable to social and cognitive biases [43]. Second, most of the studies were conducted in St. Petersburg even though 59% of HIV incidence is concentrated within 10 regions, including St. Petersburg [44]. To date, studies have been largely conducted in a few central hospitals in Russia. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other regions in Russia. Rates of alcohol and sexual risk behaviors in other cities and regions of the country that are also experiencing high rates of HIV are needed. Third, non-independence of the study samples is a possibility, as in any meta-analysis, due to the unknown number of participants participating in multiple studies. Fourth, as expected in meta-analysis, significant heterogeneity was observed in the current meta-analysis but we used methods (e.g., random-effects models, meta-regression) that are recommended to account for the observed heterogeneity [45, 46]. Fifth, even though we did not apply English-language restriction on the search, we did not find any non-English studies. This may be due to the limited indexing of Russian-language journals in the eleven electronic databases we searched. Finally, we could not conduct moderator tests for heavy drinking, alcohol abuse/dependence, condom use at last sex event, and diagnosed STIs due to the limited number of observations (k ≤ 5).

Implications for Research

Our research revealed the diverse measurements of alcohol use. This inconsistency limits analysis of the impact of alcohol use on the prevalence of sexual risk behaviors, HIV, and STIs. Future research with consistent alcohol use measures will enable a more detailed analysis of how alcohol use and problematic alcohol use are related with HIV-related risk behaviors. Furthermore, event-level research will be necessary to understand the temporal association between risky alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors, including underlying factors associated with sexual risk taking (e.g., partner type) [17]. The trend of HIV transmission from the most vulnerable groups (e.g., IDUs and sex workers) to general public through sexual contact is growing; programs to increase protective behaviors (e.g., consistent condom use) among those at high risk for STIs, including HIV, are needed. A multi-pronged approach targeting the populations in high-risk settings will be required to combat the HIV epidemic and to effectively reduce HIV infection in the country [47].

Conclusions

The prevalence of alcohol use among Russians in high-risk settings is higher than the general population. Our findings suggest that screening for risky alcohol use among Russians in high-risk settings should be a priority, followed by targeted HIV prevention. To slow the HIV epidemic in Russia, it is important to provide effective HIV prevention programming, including alcohol-related sexual risk reduction interventions that are targeted to at-risk drinkers. Screening and targeted intervention delivery could provide a cost-effective, highly efficient, and minimally burdensome approach to reducing the risk of HIV transmission in Russia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this paper was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 AA021355 to Lori A. J. Scott-Sheldon, PhD. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Because the prevalence of alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV/STIs may have changed over time, we examined publication date as a possible predictor of the observed prevalence estimates. Publication date was not a predictor of alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, or HIV/STIs, ps ≥ .06.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. The Gap Report. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piot P, Abdool Karim SS, Hecht R, et al. Defeating AIDS—advancing global health. Lancet. 2015;386(9989):171–218. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pokrovsky V, Ladnaya NN, Buravtsova EV. HIV Infection: Information bulletin #34. Russian Federal AIDS Center; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rapid increase in HIV rates--Orel Oblast, Russian Federation, 1999–2001. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2003;52(28):657–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakhmanova A, Vinogradova E, Yakovev A. The characteristics of HIV-infection in St. Petersburg. St. Petersburg: Russian Federation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balachova TN, Batluk JV, Bryant KJ, Shaboltas AV. International collaboration in HIV prevention research: evidence from a research seminar in Russia. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2015;31(2):163–72. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chenet L, McKee M, Leon D, Shkolnikov V, Vassin S. Alcohol and cardiovascular mortality in Moscow; new evidence of a causal association. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(12):772–4. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.12.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. WHO Country Profile. The Russian Federation; 2011. [Accessed June 22, 2014]. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/profiles/rus.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortenberry JD, Orr DP, Katz BP, Brizendine EJ, Blythe MJ. Sex under the influence. A diary self-report study of substance use and sexual behavior among adolescent women. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1997;24(6):313–9. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irwin TW, Morgenstern J, Parsons JT, Wainberg M, Labouvie E. Alcohol and sexual HIV risk behavior among problem drinking men who have sex with men: An event level analysis of timeline followback data. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):299–307. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prevention Science. 2007;8(2):141–51. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morojele NK, Kachieng’a MA, Mokoko E, et al. Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(1):217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Walstrom P, Carey KB, Johnson BT, Carey MP. Alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among individuals infected with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis 2012 to early 2013. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2013;10(4):314–23. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0177-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryant KJ. Expanding Research on the Role of Alcohol Consumption and Related Risks in the Prevention and Treatment of HIV/AIDS. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(10–12):1465–507. doi: 10.1080/10826080600846250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuper PA, Neuman M, Kanteres F, Baliunas D, Joharchi N, Rehm J. Causal considerations on alcohol and HIV/AIDS--a systematic review. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 2010;45(2):159–66. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 1999;75(1):3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook RL, Clark DB. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(3):156–64. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baliunas D, Rehm J, Irving H, Shuper P. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident human immunodeficiency virus infection: a meta-analysis. International journal of public health. 2010;55(3):159–66. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, Sales S, Page JB, Campa A. Alcohol use accelerates HIV disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(5):511–8. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations. 2014 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128048/1/9789241507431_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1. [PubMed]

- 23.Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2009;104(9):1487–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beyrer C, Baral SD, Walker D, Wirtz AL, Johns B, Sifakis F. The expanding epidemics of HIV type 1 among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries: diversity and consistency. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32:137–51. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. The Lancet. 2015;385(9962):55–71. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.UNAIDS. 2015 Epidemiological slides – How AIDS Changed Everything report. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. International journal of surgery. 2010;8(5):336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 1998;52(6):377–84. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fowkes FG, Fulton PM. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 1991;302(6785):1136–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6785.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baral S, Kizub D, Masenior NF, et al. Male sex workers in Moscow, Russia: a pilot study of demographics, substance use patterns, and prevalence of HIV-1 and sexually transmitted infections. AIDS care. 2010;22(1):112–8. doi: 10.1080/09540120903012551. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120903012585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdala N, Zhan WH, Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Kozlov AP, Krasnoselskikh TV. Efficacy of a Brief HIV Prevention Counseling Intervention Among STI Clinic Patients in Russia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):1016–24. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0311-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffman IF, Latkin CA, Kukhareva PV, et al. A peer-educator network HIV prevention intervention among injection drug users: results of a randomized controlled trial in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2510–20. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0563-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samet JH, Krupitsky EM, Cheng DM, et al. Mitigating risky sexual behaviors among Russian narcology hospital patients: The PREVENT (Partnership to Reduce the Epidemic Via Engagement in Narcology Treatment) randomized controlled trial. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2008;103(9):1474–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samet JH, Raj A, Cheng DM, et al. HERMITAGE-a randomized controlled trial to reduce sexually transmitted infections and HIV risk behaviors among HIV-infected Russian drinkers. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2015;110(1):80–90. doi: 10.1111/add.12716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in medicine. 2002;21(11):1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wirtz AL, Zelaya CE, Latkin C, et al. AIDS Behav. 2015. Alcohol Use and Associated Sexual and Substance Use Behaviors Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Moscow, Russia; pp. 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cook RL, Comer DM, Wiesenfeld HC, et al. Alcohol and drug use and related disorders: An underrecognized health issue among adolescents and young adults attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(9):565–70. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000206422.40319.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howards PP, Thomas JC, Earp JA. Do clinic-based STD data reflect community patterns? International journal of STD & AIDS. 2002;13(11):775–80. doi: 10.1258/095646202320753745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schroder KE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(2):104–23. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niccolai LM, Shcherbakova IS, Toussova OV, Kozlov AP, Heimer R. The potential for bridging of HIV transmission in the Russian Federation: sex risk behaviors and HIV prevalence among drug users (DUs) and their non-DU sex partners. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(Suppl 1):131–43. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9369-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higgins JPT. Commentary: Heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. International journal of epidemiology. 2008;37(5):1158–60. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2009;172(1):137–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.IOGT International. HIV and Alcohol. Sweeden: 2009. [Accessed March 10 2016]. http://ec.europa.eu/health/alcohol/docs/alcohol_lib23_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amirkhanian YA, Kelly JA, Takacs J, et al. HIV/STD prevalence, risk behavior, and substance use patterns and predictors in Russian and Hungarian sociocentric social networks of men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21(3):266–79. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eritsyan KU, Levina OS, White E, Smolskaya TT, Heimer R. HIV prevalence and risk behavior among injection drug users and their sex partners in two Russian cities. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2013;29(4):687–90. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fleming MF, Krupitsky EM, Tsoy M, et al. Alcohol and drug use disorders, HIV status and drug resistance in a sample of Russian TB patients. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2006;10(5):565–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iguchi MY, Ober AJ, Berry SH, et al. Simultaneous recruitment of drug users and men who have sex with men in the United States and Russia using respondent-driven sampling: sampling methods and implications. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(Suppl 1):5–31. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9365-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krupitsky EM, Zvartau E, Karandashova G, et al. The onset of HIV infection in the Leningrad region of Russia: a focus on drug and alcohol dependence. HIV medicine. 2004;5(1):30–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krupitsky EM, Horton NJ, Williams EC, et al. Alcohol use and HIV risk behaviors among HIV-infected hospitalized patients in St. Petersburg, Russia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79(2):251–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niccolai LM, Odinokova VA, Safiullina LZ, et al. Clients of street-based female sex workers and potential bridging of HIV/STI in Russia: results of a pilot study. AIDS care. 2012;24(5):665–72. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Odinokova V, Rusakova M, Urada LA, Silverman JG, Raj A. Police sexual coercion and its association with risky sex work and substance use behaviors among female sex workers in St. Petersburg and Orenburg, Russia. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2014;25(1):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shipitsyna E, Krasnoselskikh T, Zolotoverkhaya E, et al. Sexual behaviours, knowledge and attitudes regarding safe sex, and prevalence of non-viral sexually transmitted infections among attendees of youth clinics in St. Petersburg, Russia. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology: JEADV. 2013;27(1):e75–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vasquez C, Lioznov D, Nikolaenko S, et al. Gender disparities in HIV risk behavior and access to health care in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2013;27(5):304–10. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhan WH, Krasnoselskikh TV, Niccolai LM, Golovanov S, Kozlov AP, Abdala N. Concurrent sexual partnerships and sexually transmitted diseases in Russia. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2011;38(6):543–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318205e449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhan WH, Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Kozlov AP, Krasnoselskikh TV, Abdala N. Alcohol misuse, drinking contexts and intimate partner violence in St. Petersburg, Russia: results from a cross-sectional study. BMC public health. 2011;11:629. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhan WH, Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Krasnoselskikh TV, Abdala N. History of childhood abuse, sensation seeking, and intimate partner violence under/not under the influence of a substance: a cross-sectional study in Russia. PloS one. 2013;8(7):e68027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.