Abstract

Objective

To provide an approach to recurrent fever in childhood, explain when infections, malignancies, and immunodeficiencies can be excluded, and describe the features of periodic fever and other autoinflammatory syndromes.

Sources of information

PubMed was searched for relevant articles regarding the pathogenesis, clinical findings, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of periodic fever and autoinflammatory syndromes.

Main message

Fever is a common sign of illness in children and is most frequently due to infection. However, when acute and chronic infections have been excluded and when the fever pattern becomes recurrent or periodic, the expanding spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases, including periodic fever syndromes, should be considered. Familial Mediterranean fever is the most common inherited monogenic autoinflammatory syndrome, and early recognition and treatment can prevent its life-threatening complication, systemic amyloidosis. Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis syndrome is the most common periodic fever syndrome in childhood; however, its underlying genetic basis remains unknown.

Conclusion

Periodic fever syndromes and other autoinflammatory diseases are increasingly recognized in children and adults, especially as causes of recurrent fevers. Individually they are rare, but a thorough history and physical examination can lead to their early recognition, diagnosis, and appropriate treatment.

Fever is one of the most common presenting complaints in childhood and most frequently is due to infection. Whether febrile episodes are acute (lasting a few days) or more chronic (lasting longer than 2 weeks), infection is the most likely cause. However, if acute and chronic infections can be excluded, and if fevers are prolonged, recurrent, or periodic, the remaining differential diagnosis includes malignancy, immunodeficiency, and inflammatory conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differential diagnoses for recurrent or periodic fevers in children

| CAUSE | DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES |

|---|---|

| Infectious | |

| • Bacterial or mycobacterial | • Brucellosis, dental abscess, endocarditis, nontuberculous mycobacteria (eg, Mycobacterium chelonae), occult bacterial infection, recurrent bacterial infections, relapsing fever (Borrelia spp other than Borrelia burgdorferi), Yersinia enterocolitica |

| • Parasitic | • Malaria (eg, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale) |

| • Viral | • Epstein-Barr virus (infectious mononucleosis), hepatitis viruses, recurrent viral infections |

| Inflammatory or immunologic | Behçet syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease (eg, Crohn disease), hereditary fever syndromes (eg, FMF), juvenile dermatomyositis, PFAPA syndrome, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (Still disease), vasculitis (eg, polyarteritis nodosa) |

| Malignant | Leukemia, lymphoma |

| Other | Benign giant lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman disease), CNS abnormalities (eg, hypothalamic dysfunction), drug fever, factitious fever, IgG4-related disease, immunodeficiency syndromes with recurrent infections |

CNS—central nervous system; FMF—familial Mediterranean fever; IgG4—immunoglobulin G4; PFAPA—periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis.

Recurrent or periodic fever syndromes are defined by 3 or more episodes of unexplained fever in a 6-month period, occurring at least 7 days apart.1 These conditions are typically associated with a constellation of symptoms, including ocular, oropharyngeal, gastrointestinal, dermatologic, musculoskeletal, and neurologic manifestations. The interval between attacks of fever is irregular in some of the syndromes and fever recurs with strict periodicity in others, but the fevers resolve spontaneously without antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, or immunosuppressive therapy.2 Patients generally feel well between episodes but often suffer considerably during the attacks of fever. Although individual periodic fever syndromes are rare, they are extremely important to recognize, as appropriate diagnosis and treatment not only affects short-term morbidity and improves quality of life for patients and their families but also might prevent long-term complications that can lead to mortality. Family physicians play an important role in identifying and coordinating the investigation and ongoing management of these patients.

Case descriptions

Case 1.

Nicole is a 3-year-old girl with a history of febrile episodes since 5 months of age. The episodes recur every 2 to 4 weeks but last no more than 3 days. During the episodes, she is miserable and her parents describe persistent fever with a temperature up to 39°C, abdominal pain, and bloating. She has no rash, ocular changes, oral ulcers, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, coryza, respiratory symptoms, or musculoskeletal complaints. Antipyretics have minimal effect, and antibiotic therapy has had no effect on the duration of her episodes. Nicole has been to the emergency department on several occasions for abdominal pain associated with fever and was admitted on one occasion for overnight monitoring and intravenous fluids. During one of her typical febrile episodes, bloodwork results revealed the following: white blood cell count of 15.2 × 109/L, hemoglobin level of 118 g/L, platelet count of 389 × 109/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 18 mm/h, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 446.7 nmol/L (46.9 mg/L). Test results were negative for antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor. Nicole is an otherwise healthy child, with normal growth and development. Her family is of Turkish descent. On examination between febrile episodes she appears very well, with no focus of infection.

Case 2.

Robert is a 4-year-old boy with recurrent febrile episodes over the past 18 months, with temperatures spiking to 39.5°C to 40°C within a few hours of onset. His episodes recur every 3 to 4 weeks, last 3 to 5 days, and are associated with sore throat, tender cervical lymphadenopathy, and occasionally oral ulcers. He has no rash, ocular changes, respiratory symptoms, or musculoskeletal complaints. He is absent from day care with each episode, and his parents regularly have to take time off from work. During one of his typical febrile episodes, his bloodwork results revealed the following: white blood cell count of 11.6 × 109/L, hemoglobin level of 112 g/L, platelet count of 364 × 109/L, ESR of 26 mm/h, and a CRP level of 321.0 nmol/L (33.7 mg/L). Test results were negative for antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor. His inflammatory markers normalized following the febrile episode. Robert is an otherwise healthy child and entirely well between episodes. His family is of Japanese and Scottish descent.

Sources of information

The PubMed database was searched up to April 2016 for relevant articles regarding the pathogenesis, clinical findings, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of periodic fever and autoinflammatory syndromes. All of the identified manuscripts were full-text English-language papers.

Main message

Approach to recurrent fevers in childhood.

Although repeated febrile episodes are common in young children and often caused by acute viral infections, family members frequently worry about other potential causes such as chronic infections, immune system defects, malignancy, and inflammatory conditions. As a primary care provider, it can be challenging to identify the children who warrant further workup and potential therapy. The pattern of fever might provide clues to the underlying process (Table 2)3; however, because periodic fever syndromes tend to reveal their pattern of fever and associated features only over time, they can be difficult to identify early in the course of their presentation.

Table 2.

Fever patterns

| FEVER TYPE | FEVER PATTERN |

|---|---|

| Prolonged fever | • Single episode in which duration of fever is longer than expected for the clinical diagnosis (eg, viral syndrome lasting > 10 d) |

| Or | |

| • Single episode in which fever was initially a prominent feature but then becomes low grade or only a perceived problem | |

| Fever of unknown origin | • Single episode lasting > 3 wk during which fever is > 38.3°C on most days; diagnosis remains uncertain after 1 wk of intense evaluation |

| Recurrent fever | • Single episode during which signs (including fever) and symptoms wax and wane |

| Or | |

| • Repeated unrelated febrile episodes involving a single organ system (eg, sinopulmonary, urinary tract) | |

| Or | |

| • Repeated febrile episodes occurring at irregular intervals involving different organ systems in which fever is one variable component | |

| Periodic fever | • Recurring episodes (with either strict periodicity or irregular intervals) lasting days to weeks in which fever is the cardinal feature and other associated features are similar and predictable; intervening intervals of weeks to months characterized by complete well-being |

Adapted from Long.3

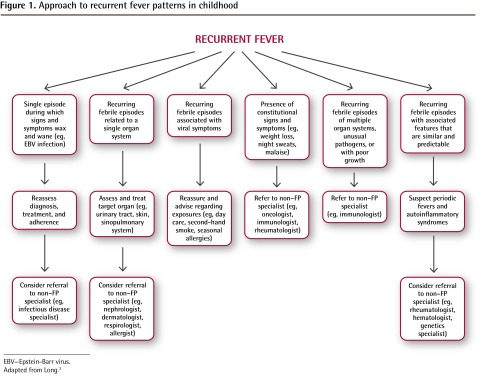

Table 3 identifies key components of the clinical history and physical examination of children who present with prolonged, recurrent, or periodic fevers.3,4 In an otherwise healthy child, a complete blood count with differential, ESR, and CRP level might be all the testing that is required. However, if the history and physical examination findings raise suspicion of a particular underlying cause, further workup is necessary. For example, if a child has a history of exposure to potential infections or other triggers (eg, had contact with a sick person, recent travel, use of prescription medications and herbal products), recurrent infections caused by unusual or opportunistic pathogens, or constitutional symptoms (eg, weight loss, night sweats, malaise), additional investigations are warranted (Table 3) and a referral to a specialist might be indicated (Figure 1).3 Once infections, immunodeficiency, malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and adverse drug reactions have been ruled out, autoinflammatory diseases—including periodic fever syndromes—should be considered.

Table 3.

Factors to consider when examining a child with prolonged, recurrent, or periodic fever

| EXAMINATION ELEMENTS | CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|

| Clinical history |

|

| Physical examination |

|

| Investigations |

|

CRP—C-reactive protein, ESR—erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Figure 1.

Approach to recurrent fever patterns in childhood

EBV—Epstein-Barr virus.

Adapted from Long.3

Periodic fever syndromes and other inherited auto-inflammatory diseases.

The term autoinflammation describes a state of seemingly unprovoked inflammation. Whereas the more classically recognized autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus are characterized by dysregulation of the adaptive immune system (with high-titre autoantibodies and proliferation of antigen-specific T cells), the autoinflammatory diseases relate to inborn errors of the innate immune system.2,5 Hereditary periodic fever syndromes were the first group of monogenic disorders to be classified as auto-inflammatory, but many more continue to be described (Table 4).6,7

Table 4.

Periodic fever syndromes and other inherited autoinflammatory diseases

| CONDITION | MODE OF INHERITANCE |

|---|---|

| Periodic fever syndrome without known inheritance | |

| • PFAPA syndrome | None |

| Periodic fever syndrome with known inheritance | |

| • FMF | AR |

| • Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes | |

| -Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome | AD |

| -Muckle-Wells syndrome | AD |

| -Neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease | AD or de novo |

| • Mevalonate kinase deficiency (hyper-IgD with periodic fever syndrome) | AR |

| • Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome 2 | AD |

| • TRAPS | AD |

| • Cyclic hematopoiesis or cyclic neutropenia | AD or de novo |

| Diseases with pyogenic lesions | |

| • Deficiency of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist | AR |

| • Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne syndrome | AD |

| Diseases with granulomatous lesions | |

| • Blau syndrome | AD |

| Diseases with psoriasis | |

| • Deficiency of interleukin-36 receptor antagonist | AR |

| • CARD14-mediated psoriasis | AD |

| Interferonopathies; diseases with panniculitis-induced lipoatrophy | |

| • CANDLE syndrome | AR |

| • Joint contractures, muscle atrophy, and panniculitis-induced lipodystrophy syndrome | AR |

| • Nakajo-Nishimura syndrome | AR |

| • Aicardi-Goutières syndrome | AR |

| Others | |

| • PLCγ2-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation syndrome | AD |

| Polygenic autoinflammatory diseases* | |

| • Behçet disease | Unknown |

| • Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis | Unknown |

| • Gout | Unknown |

| • Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Unknown |

AD—autosomal dominant; AR—autosomal recessive; CANDLE—chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature; CARD14—caspase recruitment domain family member 14; FMF—familial Mediterranean fever; hyper-IgD—hyperimmunoglobulin D; PFAPA—periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis; PLCγ2—phospholipase Cγ2; TRAPS—tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic syndrome.

Many more polygenic autoinflammatory diseases continue to be described.

The spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases is now thought to include several other conditions such as gout, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, adult-onset Still disease, and Behçet syndrome. Whether these latter conditions prove to be polygenic in origin, with contributions from both innate and adaptive immunity, is an area of ongoing research.2,5,7

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF).

First described in 1945,8 FMF (also known as familial paroxysmal polyserositis) is the most common and well known monogenic autoinflammatory syndrome. Characterized by seemingly unprovoked recurrent attacks of fever and inflammatory serositis, arthritis, and rash, FMF results from autosomal recessive mutations in the MEFV (MEditerranean FeVer) gene on chromosome 16p.9,10 Familial Mediterranean fever is most prevalent among Sephardi- and Ashkenazi-Jewish, Armenian, Arab, Italian, and Turkish populations, with carrier rates as high as 1:3 to 1:5.11

Clinical signs and symptoms of FMF develop in 20% of patients by age 2, in 50% by age 10, and in 90% by age 20.11 A typical attack lasts between 12 and 72 hours, with fever peaking soon after onset. Abdominal pain (often mimicking appendicitis) accompanies fever in more than 90% of patients,12 whereas arthritis (50% to 75%),13 pleuritis (30% to 45%),11,14 erysipelas-like rash (7% to 40%),15 and pericarditis (<1%)16 occur less commonly. Because fever can be the only manifestation of an attack, especially in younger children, FMF should be considered in the differential diagnosis of all children with recurrent fevers, particularly in the aforementioned ethnic groups.7

The diagnosis of FMF is made based on clinical findings rather than genetic testing.17 In children, criteria proposed in 2009 require recurrent (≥3) attacks with at least 2 of the following 5 features: fever lasting between 12 and 72 hours, abdominal pain, chest pain, arthritis, and a positive family history for FMF.18 During attacks, acute phase reactant levels (including CRP, serum amyloid A, fibrinogen, and complement) increase, and leukocytosis and elevated ESR might also be found.11 The acute phase serum protein levels can remain elevated even between attacks, which predisposes patients to systemic amyloidosis, the life-threatening complication of FMF. Colchicine, the treatment of choice, prevents amyloidosis in nearly all patients and prevents attacks in 60% to 70% of patients; however, 20% to 30% of patients only partially respond, and 5% are nonresponders.19 In these latter cases, interleukin-1 inhibitors might be effective.20

Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome.

First described in 1987,21 PFAPA is the most common periodic fever syndrome. It has yet to be characterized by a known genetic mutation or underlying cause. The onset of PFAPA is almost always before the age of 5. Other than cyclic hematopoiesis (also known as cyclic neutropenia), PFAPA is the only autoinflammatory condition with strict “clocklike” periodicity between attacks of fever (parents can often predict the first day of fever). In any individual child, the interval between episodes is nearly constant, usually every 21 to 28 days, with fever lasting 3 to 5 days and associated features nearly identical.22

Clinically, aphthae (shallow ulcers in the buccal mucosa and pharynx that heal without scarring) have been reported in 70% of patients.22,23 Pharyngitis (consisting of erythematous, enlarged tonsils) and cervical adenitis are present in 80% to 100% of patients; generalized lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly suggests a diagnosis other than PFAPA.22,24 Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, arthralgia, and headaches might also occur but are usually mild. During attacks, mild leukocytosis with neutrophilia and a modest left shift can occur along with elevation of acute phase reactants such as CRP levels and ESR. Throat cultures are negative for microorganisms in 90% of patients,22 with positive findings likely representing benign carriage, as the natural history of each attack is not affected by antibiotic therapy.

The diagnosis of PFAPA is made based on clinical findings once other causes of recurrent fevers in children have been excluded. Children must be completely asymptomatic (with normal levels of acute phase reactants) during interval periods and demonstrate normal growth and development. Diagnostic criteria for PFAPA are summarized in Box 1.24 Although no long-term complications have been reported in patients with PFAPA, there is a considerable effect on quality of life that includes disruptions of family routine. Treatment with antibiotics and colchicine is generally ineffective; however, a single dose of prednisone (0.6 to 2 mg/kg) at the onset of symptoms and, if necessary, the following day can abort the attack in almost all patients. Inexplicably, prednisone might actually shorten the interval between episodes.21,22 Cimetidine (40 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses) might prevent recurrences in one-third of patients.25 For children requiring frequent corticosteroids or with marked effect on quality of life, tonsillectomy (with or without adenoidectomy) has been shown to induce remission compared with control groups.26

Box 1. Diagnostic criteria for PFAPA syndrome.

Diagnostic criteria for PFAPA syndrome include the following:

Onset of disease in early childhood, generally before the age of 5 y

- Regularly recurring abrupt episodes of fever lasting approximately 5 d, associated with constitutional symptoms and both of the following:

- - aphthae or pharyngitis (with or without cervical adenitis) in the absence of other signs of respiratory tract infection

- - acute inflammatory markers such as leukocytosis or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Completely asymptomatic interval periods (generally lasting less than 10 wk) benign long-term course, normal growth parameters, and the distinct absence of sequelae

Exclusion of cyclic neutropenia by serial neutrophil counts before during and after symptomatic episodes

Exclusion of other episodic syndromes (FMF, hyper-IgD syndrome, TRAPS, Behçet syndrome) by family history and the absence of typical clinical features and laboratory markers

Absence of clinical and laboratory evidence for immunodeficiency, autoimmune disease, or chronic infection

FMF—familial Mediterranean fever; hyper-IgD—hyperimmunoglobulin D; PFAPA—periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis; TRAPS—tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic syndrome. Data from Marshall et al.24

Prognosis is excellent, and patients do not develop amyloidosis. Although the frequency and severity of attacks tend to resolve in adolescence, up to 15% of patients might continue to experience attacks for at least 18 years.27

Role of genetic testing.

If a clinical pattern consistent with one of the autoinflammatory diseases can be identified, the family and physician often seek confirmation with genetic testing. A genetic diagnosis should be pursued in a logical manner recognizing the cost and limitations of testing. A simple interactive tool is available online (www.printo.it/periodicfever/), and the resultant diagnostic score can be used to stratify the risk of a genetic periodic fever syndrome in a patient with recurrent fever.28 Worth noting is that the diagnosis of a child with a periodic fever syndrome is much more challenging in a multiethnic population than in regions with high prevalence for a particular condition (such as FMF). For this reason, validation of the algorithms and decision tools for the genetic testing of the expanding spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases is ongoing.

Case resolutions

Case 1.

Three-year-old Nicole had a classic presentation of, including the ethnic background for, FMF. Her diagnostic score for periodic fever, calculated with the online interactive tool, placed her at high risk of a monogenic periodic fever syndrome. Genetic testing revealed homozygosity for the most common FMF-associated mutation: M694V. She was started on colchicine daily, with near-complete remission of her symptoms. She will require treatment with colchicine all her life; fortunately colchicine is safe to use during pregnancy and has been reported to improve pregnancy outcomes in women with FMF. Thus far, urinalyses and serum amyloid A screening results have remained negative; however, she will be monitored for amyloidosis her entire life and will receive genetic counseling should she consider having children of her own.

Case 2.

Four-year-old Robert demonstrated a clinical pattern consistent with PFAPA syndrome. His diagnostic score for periodic fever placed him at low risk for a monogenic periodic fever syndrome, and no genetic testing was performed. The frequency of his attacks did not improve with regular use of cimetidine. Although treatment with prednisone was successful in aborting an attack when given on the first day of fever, the frequency of his episodes increased, much to the disappointment of his parents. He ultimately underwent adenotonsillectomy, with complete resolution of his symptoms.

Conclusion

The differential diagnosis of fever in childhood is extensive and can be daunting when recurrent or periodic fever patterns persist despite exclusion of acute and chronic infections, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancy. The expanding spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases—including the most commonly encountered periodic fever syndromes such as FMF and PFAPA— should be considered in such patients. A thorough history (including family pedigree), targeted physical examination, and thoughtful investigations often lead to a diagnosis.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Although periodic fever syndromes are rare, they are important to recognize, as appropriate diagnosis and treatment affects short-term morbidity, improves patients’ quality of life, and also might prevent long-term complications that can lead to mortality.

The differential diagnosis of fever in childhood can be daunting when recurrent or periodic fever patterns persist despite exclusion of acute and chronic infections, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancy. The expanding spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases—including the most commonly encountered periodic fever syndromes such as familial Mediterranean fever and periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis syndrome—should be considered in such patients. A thorough history (including family pedigree), targeted physical examination, and thoughtful investigations often lead to a diagnosis.

Footnotes

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro d’octobre 2017 à la page e408.

Contributors

Both authors contributed to the literature review and interpretation, and to preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

Dr Laxer has served on advisory boards for and acted as a consultant to Novartis and Sobi; both are producers of anti–interleukin-1 products.

References

- 1.John CC, Gilsdorf JR. Recurrent fever in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21(11):1071–7. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200211000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barron KS, Kastner DL. Periodic fever syndromes and other inherited auto-inflammatory diseases. In: Petty RE, Laxer RM, Lindsely CB, Wedderburn LR, editors. Textbook of pediatric rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 609–26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long SS. Distinguishing among prolonged, recurrent, and periodic fever syndromes: approach of a pediatric infectious diseases subspecialist. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52(3):811–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashkes PJ, Toker O. Autoinflammatory syndromes. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012;59(2):447–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masters SL, Simon A, Aksentijevich I, Kastner DL. Horror autoinflammaticus: the molecular pathophysiology of autoinflammatory disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:621–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aksentijevich I, Masters SL, Ferguson PJ, Dancey P, Frenkel J, van Royen-Kerkhoff A, et al. An autoinflammatory disease with deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(23):2426–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozen S, Bilginer Y. A clinical guide to autoinflammatory diseases: familial Mediterranean fever and next-of-kin. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(3):135–47. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.174. Epub 2013 Nov 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegal S. Benign paroxysmal peritonitis. Ann Intern Med. 1945;22:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 9.International FM Consortium Ancient missense mutations in a new member of the RoRet gene family are likely to cause familial Mediterranean fever. Cell. 1997;90(4):797–807. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.French FM Consortium A candidate gene for familial Mediterranean fever. Nat Genet. 1997;17(1):25–31. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuels J, Aksentijevich I, Torosyan Y, Centola M, Deng Z, Sood R, et al. Familial Mediterranean fever at the millennium. Clinical spectrum, ancient mutations, and a survey of 100 American referrals to the National Institutes of Health. Medicine (Baltimore) 1998;77(4):268–97. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sohar E, Gafni J, Pras M, Heller M. Familial Mediterranean fever. A survey of 470 cases and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1967;43(2):227–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(67)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Gonzalez A, Weisman MH. The arthritis of familial Mediterranean fever. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1992;22(3):139–50. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(92)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tunca M, Akar S, Onen F, Ozdogan H, Kasapcopur O, Yalcinkava F, et al. Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) in Turkey: results of a nationwide multi-center study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2005;84(1):1–11. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000152370.84628.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drenth JP, van der Meer JW. Hereditary periodic fever. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(24):1748–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucuk A, Gezer IA, Ucar R, Karahan AY. Familial Mediterranean fever. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2014;57(3):97–104. doi: 10.14712/18059694.2014.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livneh A, Langevitz P, Zemer D, Zaks N, Kees S, Lidar T, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(10):1879–85. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yalçinkaya F, Ozen S, Ozçakar ZB, Aktay N, Cakar N, Düzova A, et al. A new set of criteria for the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever in childhood. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(4):395–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken509. Epub 2009 Feb 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zemer D, Pras M, Sohar E, Modan M, Cabili S, Gafni J. Colchicine in the prevention and treatment of the amyloidosis of familial Mediterranean fever. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(16):1001–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198604173141601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozen S, Bilginer Y, Aktay Ayaz N, Calguneri M. Anti-interleukin 1 treatment for patients with familial Mediterranean fever resistant to colchicine. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(3):516–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100718. Epub 2010 Dec 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall GS, Edwards KM, Butler J, Lawton AR. Syndrome of periodic fever, pharyngitis, and aphthous stomatitis. J Pediatr. 1987;110(1):43–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas KT, Feder HM, Jr, Lawton AR, Edwards KM. Periodic fever syndrome in children. J Pediatr. 1999;135(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofer M, Pillet P, Cochard MM, Berg S, Krol P, Kone-Paut I, et al. International periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, cervical adenitis syndrome cohort: description of distinct phenotypes in 301 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53(6):1125–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall GS, Edwards KM, Lawton AR. PFAPA syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8(9):658–9. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198909000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feder HM., Jr Cimetidine treatment for periodic fever associated with aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and cervical adenitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11(4):318–21. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199204000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garavello W, Pignataro L, Gaini L, Torretta S, Somigliana E, Gaini R. Tonsillectomy in children with periodic fever with aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis syndrome. J Pediatr. 2011;159(1):138–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.12.014. Epub 2011 Feb 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wurster VM, Carlucci JG, Feder HM, Jr, Edwards KM. Long-term follow-up of children with periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis syndrome. J Pediatr. 2011;159(6):958–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.06.004. Epub 2011 Jul 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gattorno M, Sormani MP, D’Osualdo A, Pelagatti MA, Caroli F, Federici S, et al. A diagnostic score for molecular analysis of hereditary autoinflammatory syndromes with periodic fever in children. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(6):1823–32. doi: 10.1002/art.23474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]