Abstract

A simple and convenient method is described to determine primary deuterium kinetic isotope effects (1°DKIE) on reactions where the hydron incorporated into the reaction product is derived from solvent water. The 1°DKIE may be obtained by 1H NMR analyses, as the ratio of the yields of -H and -D labelled products from a reaction in 50:50 (v/v) HOH/DOD. The procedures for these 1H NMR analyses are reviewed. This product deuterium isotope effect (PDIE) is defined as 1/ϕEL for fractionation of hydrons between solvent and the transition state for the reaction examined. When solvent is not the direct hydron donor, it is necessary to correct the PDIE for the fractionation factor ϕEL for partitioning of the hydron between solvent and the direct donor EL. This method was used to determine the 1°DKIE on decarboxylation reactions catalyzed by wildtype orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC) and by mutants of OMPDC, and then in the determination of the 1°DKIE on the decarboxylation reaction catalyzed by 5-carboxyvanillate decarboxylase. The experimental procedures used in studies on OMPDC, and the rationale for these procedures are described.

Keywords: Decarboxylation, Proton Transfer, Kinetic Isotope Effects, Reactive Intermediates, Enzyme Catalysis

1. Introduction

A simple and powerful experiment to characterize enzymatic reaction mechanisms is the determination of the effect of a change from HOH as a solvent to DOD on the reaction rate (Kresge, More O’Ferrall and Powell, 1987, Schowen, 1972). The interpretation of solvent deuterium kinetic isotope effects (SDKIE) requires a consideration of both the secondary solvent isotope effects on reactivity of the hydroxylic solvent water (Jencks, 1987), and of the primary deuterium kinetic isotope effect (1°DKIE) on the rate of hydron transfer that arises from the difference in ground state zero-point energy that is lost at the transition state for cleavage of X-H compared with X-D bonds (Westheimer, 1961).

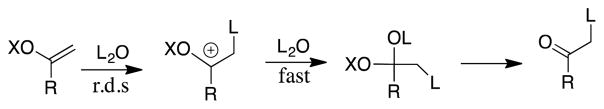

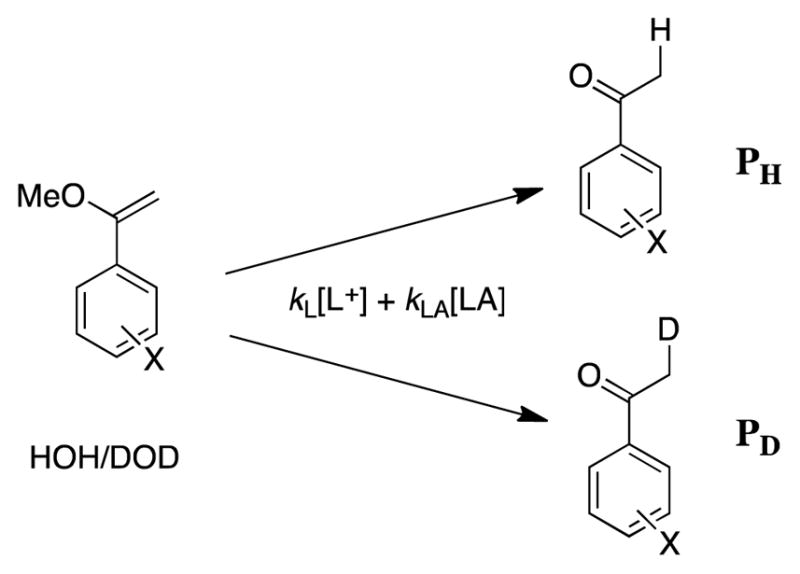

These complications were examined and clarified in studies on the hydrolysis of vinyl ethers that proceed with rate determining protonation of the substrate to form an oxocarbenium ion (Scheme 1)(Richard and Williams, 2007, Tsang and Richard, 2007, Tsang and Richard, 2009). The ratio of second-order rate constants kH/kD determined for specific-acid catalyzed hydrolysis of vinyl ethers in HOH and DOD is smaller than the 1°DKIE on proton transfer (Kresge, Sagatys and Chen, 1977). For example, the ratio kH/kD = 4.0 for specific-acid catalyzed hydrolysis of α-methoxystyrene in HOH and DOD, is smaller than the 1°DKIE of 5.7 determined as described below, because of an inverse contribution from a secondary secondary SDKIE of 0.70. (Tsang and Richard, 2009). This SDKIE arises because hydrogen bonds between solvent and -H at H3O+ are stronger than between solvent and -D at D3O+ (Jencks, 1987, Kresge, More O’Ferrall and Powell, 1987, Schowen, 1972). The weakening of hydrogen bonds to lyonium ion at the transition state for specific-acid catalyzed reactions therefore results in a larger increase in the barrier for protonation by H3O+, where the hydrogen bonds are strongest, compared with D3O+: this is the underlying cause for the observed inverse SDKIE.

Scheme 1.

The mechanism for hydrolysis of a simple vinyl ether to form the ketone. There is extensive evidence that protonation of the vinyl ether to form the oxocarbenium ion is effectively irreversible and the rate determining step for the hydrolysis reaction, because the barrier to deprotonation of this intermediate to regenerate the vinyl ether is several kcal/mol higher than the barrier for addition of solvent to form the hemiacetal intermediate (Richard, Amyes, Lin and A. C. M. O’Donoghue, 2000, Richard and Williams, 2007, Richard, Williams and Amyes, 1999).

| (1) |

The 1°DKIEs on protonation of ring-substituted α-methoxystyrenes may be obtained, free of any contribution from a SDKIE, by examining the reactions of -H and -D in a common mixed solvent. The 1°DKIE on the rate determining proton transfer step is obtained from the product deuterium isotope effect (PDIE) determined using eq 1, where fH and fD are the mole fractions of H and D in the mixed solvent and [PH]/[PD] is the ratio of the yield of the -H and -D labelled products. This ratio is determined as the ratio of the area ACH3 of the peak for the singlet due to the -CH3 group and ACH2D for the upfield shifted triplet due to the -CH2D group

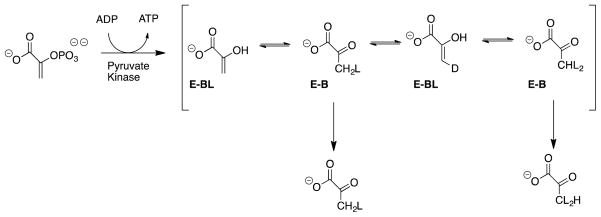

This experimental protocol can be adapted to enzyme-catalyzed reactions of vinyl ethers and vinyl phosphates. In practice, experiments to determine the 1°DKIE for protonation of an enzyme-bound enol pyruvate intermediate by pyruvate kinase failed (Kuo, O’Connell and Rose, 1979, Robinson and Rose, 1972), because proton transfer at the enzyme active site is reversible (Scheme 3) and results in formation of didueterium labelled pyruvate at early reaction times [W. Tsang and J. Richard, unpublished results].

Scheme 3.

Pyruvate kinase catalyzed phosphorylation of ADP in 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD. This reaction gives a mixture mono- and didueterium labelled pyruvate during the first enzyme turnover of substrate [W. Tsang and J. P. Richard, unpublished results].

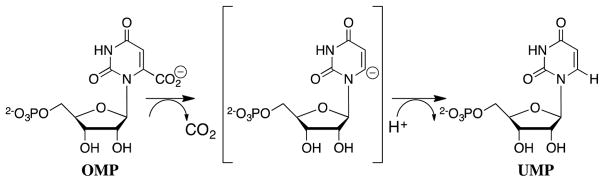

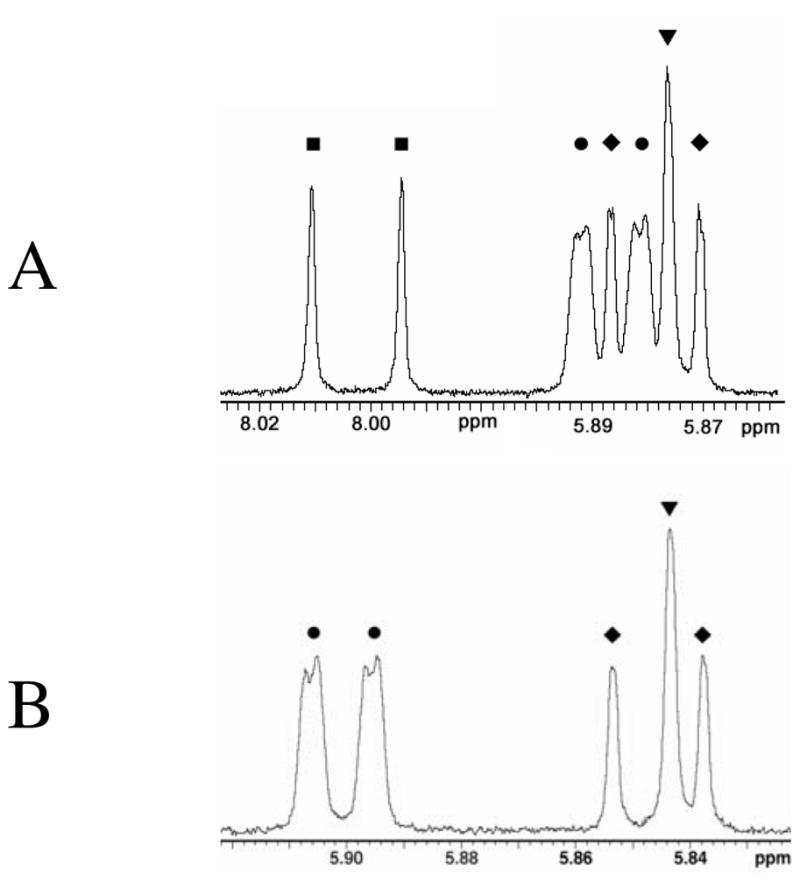

2. Enzyme-Catalyzed Decarboxylation of OMP

A proton from solvent is substituted for CO2 in enzyme-catalyzed decarboxylation. Enzyme-catalyzed decarboxylation proceeds by a stepwise mechanisms, through a carbanion reaction intermediate, when the negative charge at carbon is delocalized onto a second electron-deficient atom, such as an enolate oxygen (Richard, 1990). Orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC, Scheme 4) catalyzes the chemically difficult decarboxylation of orotidine 5′-monophosphate (OMP) (Miller and Wolfenden, 2002), where the negative charge at the vinyl carbanion reaction intermediate is largely localized at carbon-6 (Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2008, Tsang, et al., 2012). There is considerable interest in understanding the mechanism by which OMPDC enables formation of this unstable vinyl carbanion reaction intermediate.

Scheme 4.

OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP through a vinyl carbanion reaction intermediate (Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2008, Tsang, Wood, Wong, Wu, Gerlt, Amyes and Richard, 2012).

The SDKIE of 1.3 on kcat/Km for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation in HOH and DOD shows that there are only small changes in bonding at solvent derived hydrons on proceeding from free enzyme and substrate to the rate-determining transition state for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation (Ehrlich, Hwang, Cook and Blanchard, 1999). This SDKIE may be dominated by the effect of changes in the strength of hydrogen bonding interactions to protein-bound hydrons (Chang, et al., 1996, Kresge, 1973). The small observed SDKIE shows that there can be no more than a small 1° DKIE on the rate-determining step for enzyme-catalyzed decarboxylation, and is consistent with rate determining loss of CO2 to form a UMP carbanion reaction intermediate (Scheme 4). These results do not bear directly on the magnitude of the 1° DKIE on the proton transfer reaction to C-6 of UMP for a concerted reaction mechanism (not shown) (Appleby, Kinsland, Begley and Ealick, 2000, Begley and Ealick, 2004), or to C-6 of the UMP carbanion intermediate of a stepwise reaction (Scheme 4).

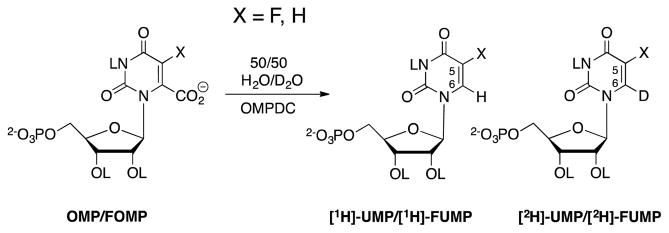

We were interested in characterizing the extent of bonding to the proton transferred from an acidic side chain of OMPDC to the C-6 carbon at the product determining transition state for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation. This is defined by the 1° DKIE on the hydron transfer reaction, which provides a measure for the fraction of the original zero-point energy of the original bond to hydrogen that is maintained at the transition state for the product determining step (Westheimer, 1961). The 1° DKIE on OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP and 6-fluoroorotidine 5′-monophosphate (FOMP) were obtained, independent of contributions from solvent deuterium isotope effects, by determining the yields of -H and -D labelled products formed in a common solvent of 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD (Scheme 5) (Toth, Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2007, Toth, Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2010). We describe here the protocol for the determination of these product isotope effects.

Scheme 5.

The decarboxylation of OMP or FOMP a mixed solvent catalyzed by OMPDC to give a mixture of -H and -D labeled reaction products. The primary isotope effect on hydron transfer is calculated from the ratio of the yields -H ([PH]) and -D ([PD]) labelled products using eq 2.

3. Experimental Protocol

3.1 A comparison of protocol for determination of SDIE and PDIE

We first consider the strengths and limitations of the different protocol for determination of PDIEs for reactions in a mixed solvent of 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD and for determination of SDKIEs for separate reactions in HOH and DOD.

The uncertainty in the value for the PDIE is small, because the transfer of -H and -D are examined under identical reaction conditions. The experimental error arises from the uncertainty in the yields of -H and -D labeled reaction products, calculated from the areas of the relevant NMR product peaks (eq 1). These areas can generally be determined to better than ±1% for each product, to give an uncertainty in the PDIE of better than ±2% (Tsang and Richard, 2009). A similar small uncertainty may possible for the SDIE, determined as the ratio of rate constants for separate experiments in HOH and DOD, provided the differences in the temperature of the runs is minimized by carrying the reactions out in parallel and with a single bath to control temperature.

- The determination of the SDIE on OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation requires an analytical method to continuously monitor conversion of substrate OMP to product UMP. It is not necessary to continuously monitor decarboxylation to obtain the PDIE, but an analytical method is needed to determine the yields of -H and -D labeled UMP products at the end of the reaction. The detection of reaction products by NMR analysis is generally less sensitive than detection by UV-Vis spectroscopy. This will complicate the determination of the PDIE, when the reactant is sparingly soluble in the aqueous solvent (Tsang and Richard, 2007, Tsang and Richard, 2009).

(2) (3) The value of the SDIE on OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation is a function of the complex secondary solvent deuterium isotope effects on enzyme reactivity (Kresge, More O’Ferrall and Powell, 1987, Schowen, 1972, Schowen, 2007), and of the intrinsic 1° DKIE on hydron transfer [see above]. By comparison the PDIE depends only on the fractionation factor (ϕTS, eq 2) for partitioning of the transferred hydron between the mixed solvent and the transition state for enzyme-catalyzed decarboxylation. The hydron that is donated to form the product of OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation is derived from the cationic ammonium side chain of Lys93 (Miller, Hassell, Wolfenden, Milburn and Short, 2000). The kinetic deuterium isotope effect on the reaction of the side chain labeled with -H (kEH) and with -D (kED) is related to the product isotope effect by the term ϕEL ≈ 1.0 (eq 3) for fractionation of the hydron between solvent and the ammonium side chain of Lys93 (Jarret and Saunders, 1986, Schowen and Schowen, 1982). The fractionation factor of ϕEL ≈ 1.0 shows that the deuterium enrichment of the acidic side chain is essentially the same as water, so that the product DIE is equal to the 1° DKIE on proton transfer from the -H and -D labelled side chains.

3.2. Enzyme-catalyzed decarboxylation

A single stock solution of 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD [1.00/1.00 molar ratio] is used for the preparation of all buffer solutions. Solutions of concentrated OMPDC were extensively dialyzed against the standard buffer of 50 mM MOPS buffer (50% free base) at pL 7.4 and an ionic strength of 0.1 (NaCl) in 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD. Standard assays described in earlier work were used to determine the activity of OMPDC for decarboxylation of OMP (Barnett, Amyes, Wood, Gerlt and Richard, 2008). The enzyme concentrations used in these studies were sufficient to give decarboxylation of ca. 95% of the substrate in several hours.

Similar reaction conditions were used for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP and FOMP. The decarboxylation of 2 mM substrate was carried out in 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD (2.0 mL) that contained 50 mM MOPS buffer (50% free base) at pL 7.4 and an ionic strength of 0.10 (NaCl). The reactions were initiated by addition of OMPDC and the reaction progress was determined periodically from the decrease in absorbance at 279 nm (Δε = 2400 M cm−1) or 282 nm (Δε = 1380 M cm−1) for enzyme-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP and FOMP, respectively. A wide range of enzyme concentrations (0.01 – 30 μM) were used, due to the large falloff in the activity for mutant forms of OMPDC examined (Barnett, Amyes, McKay Wood, Gerlt and Richard, 2010, Barnett, Amyes, Wood, Gerlt and Richard, 2008). OMPDC is stable for several days under these conditions.

When the reaction was judged to have reached 95% completion (x min) an 800 μL aliquot was withdrawn and the enzyme was removed by ultrafiltration using Microcon® Centrifugal Filter Units (10K molecular weight cutoff). After an additional reaction time of x min a second 800 μL aliquot was withdrawn and treated in the same manner. The filtered solutions were frozen and saved for NMR analysis. Prior to 1H NMR analyses, the solutions of OMP were generally adjusted to 9.5 – 10 using NaOD, in order to increase the resolution of the signals for the 5-H and 1′-H of UMP. The solutions of FUMP were kept at the initial pH of 7.4 for 19F-NMR analysis

NMR analyses of product yields

These experiments are designed to obtain a single experimental value; the deuterium enrichment of the product of the reaction in 50/50 HOH/DOD. This enrichment is obtained by integration of the appropriate NMR peaks for -H and -D labeled products, determined by averaging multiple Fourier-transform NMR spectra. Errors in peak areas may arise by failure of allow complete relaxation of nuclei between Fourier transform pulses. These errors were minimized by determining the relaxation times T1 for all nuclei of interest, and then using a relaxation delay between pulses of > 7T1 for all nuclei.

The yields of [6-1H]-UMP and [6-2H]-UMP were determined by 1H NMR analyses at 500 Mz. The spectra (ca 30 transients) were recorded for a 6000 Hz spectral width, and with suppression of the water peak, using a 90° pulse angle, a 6 s acquisition time, and a 120 s relaxation delay between pulses (> 7T1). The yields of [6-1H]-FUMP and [6-2H]-FUMP were determined by 19F NMR analyses at 470 MHz. The spectra (64 transients) were recorded for a 50000 Hz spectral width; and, using a 90° pulse angle, a 2.6 s acquisition time, and a 20 s relaxation delay between pulses (> 7T1).

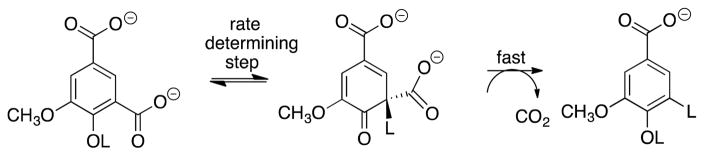

The product spectra were analyzed in regions sensitive to the deuterium enrichment at carbon-6 of UMP or FUMP. Figure 1 shows representative partial 1H NMR spectra from decarboxylation of OMP catalyzed by OMPDC in 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD obtained at pH 7.4 (Figure 1A) and 9.7 (Figure 1B), respectively. In early studies the yield of UMP labeled with hydrogen at C-6 was obtained from the integrated area of the doublet due to the C-6 proton at 7.990 ppm (■, Figure 1A) and the yield of [6-2H]-UMP was obtained from the area of the collapsed singlet due to the C-5 proton at 5.865 ppm (▼, Figure 1A) (Toth, Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2007). The spectrum at pL 7.4 shows overlap between the signals for the C-5 pyrimidine and the C-1′ anomeric ribosyl hydrogen. The spectral resolution at pL 9.7 is improved due to the effect on chemical shift of partial ionization of N-3 of UMP (pKa = 9.45) (Massoud and Sigel, 1988) on chemical shift. In later studies the spectral analyses were carried out at pL 9.7 (Figure 1B), and the PDIE calculated from the ratio of the integrated area of the doublet at 5.846 ppm for the C-5 hydrogen of [6-1H]-UMP and of the collapsed singlet at 5.843 ppm for the C-5 hydrogen of [6-2H]-UMP (Toth, Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2010). The PDIE was determined as the ratio of these peak areas for UMP labeled with [1H] (AH) and [2H] (AD) at C-6 (eq 4).

Figure 1.

(A) Partial 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz) at pL 7.4 of the UMP product of decarboxylation of OMP catalyzed by ScOMPDC (0.024μM) in 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD at 25 ˚C. Key: (■), Doublet due to the C-6 proton of [6-1H]-UMP; (●), poorly resolved double doublets due to the anomeric protons of [6-1H]-UMP and [6-2H]-UMP; (◆), doublet due to the C-5 proton of [6-1H]-UMP; (▼), collapsed singlet due to the C-5 proton of [6-2H]-UMP. (B) Partial 1H NMR spectrum determined at pL 9.7. Key: (●), Double doublets due to the anomeric protons of [6-1H]-UMP and [6-2H]-UMP; (◆), doublet due to the C-5 proton of [6-1H]-UMP; (▼), collapsed singlet due to the C-5 proton of [6-2H]-UMP. Reproduced from (Toth, Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2010) with permission. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

| (4) |

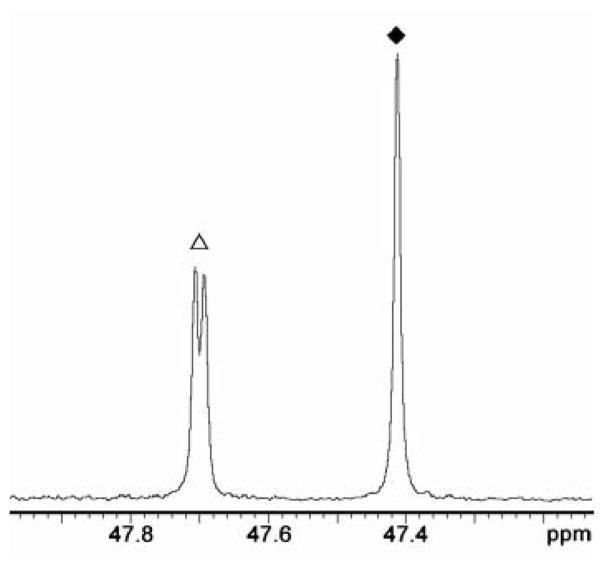

Figure 2 shows a representative 19F-NMR spectrum (470 MHz) at pL 7.4 of 5-FUMP obtained from the decarboxylation of 5-FOMP (2 mM) catalyzed by R235A mutant ScOMPDC. Separate 19F signals are observed for [6-1H]-5-FUMP and [6-2H]-5-FUMP because the C-6 deuterium perturbs the 19F-chemical shift of the C-5 fluorine by 0.29 ppm. The product deuterium isotope effect was determined as the ratio of the integrated area of the doublet at 47.70 ppm (JHF = 6 Hz) for [6-1H]-5-F-UMP and of the downfield-shifted singlet at 47.41 for [6-2H]-5-FUMP. In all cases the PDIEs (eq 4) were determined at two different reaction times.

Figure 2.

The 470 MHz 19F NMR spectrum of 5-FUMP, which is the product of decarboxylation of 5-FOMP catalyzed by R235A ScOMPDC (0.054 μM) in 50/50 HOH/DOD (v/v) at pL 7.4. Key: (△), doublet at δ = 47.70 ppm (JHF = 6 Hz) due to the fluorine at [6-1H]-5-FUMP; (◆), downfield-shifted singlet at δ = 47.41 ppm due to the fluorine at [6-2H]-5-FUMP. Reproduced from (Toth, Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2010) with permission. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

4. Interpretation of Results

The interpretation of the magnitude of the PDIE is straight forward. The large thermodynamic driving force for protonation of the vinyl carbanion reaction intermediate ensures that hydron transfer is irreversible (Tsang, Wood, Wong, Wu, Gerlt, Amyes and Richard, 2012), so that the yields of -H and -D labelled products are determined entirely by the relative barriers for hydron transfer from OMPDC. We find that the decarboxylation of OMP in 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD catalyzed by OMPDC from S. cerevisiae, M. thermautotrophicus and E. coli gives essentially equal yields of the corresponding -H and -D labelled products. This gives a value of 1.0 for the PDIE (Toth, Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2007). The agreement from two different determinations is generally ±2% or better.

The values of 1.0 and 0.9 for the PDIE for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP and FOMP, respectively, do not change as kcat/Km is reduced 104- fold by site-directed mutations (Toth, Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2010). This represents a rare example of a complete lack of selectivity for the transfer H and D from solvent to the reaction product (Macciantelli, Seconi and Eaborn, 1978), which requires that the zero-point energy associated with the bonds to the reacting hydrons not change as the hydron moves from the mixed HOH/DOD solvent to the product-determining transition state for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation. The results show that proton transfer from OMPDC to C-6 of OMP does not provide electrophilic push to the loss of CO2 in a concerted reaction (Begley, Appleby and Ealick, 2000, Begley and Ealick, 2004), even when there is a very large barrier to reactions catalyzed by mutant OMPDC enzymes. The lack of selectivity between the reaction of -H and -D is consistent with restricted C-N bond rotation of the donor -CH2-NL3+ group of the side-chain of Lys-93. This ensures that protonation of the intermediate is faster than bond rotation that would allow the intermediate to select between reaction of -H and -D. We proposed that hydrogen bonds from the CH2-NL3+ group of Lys-93 to the carboxylate groups of Asp-91 and Asp-96 restricts rotation about the carbon-nitrogen bond and directs the single unliganded hydron towards the C-6 UMP carbanion (Toth, Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2007, Toth, Amyes, Wood, Chan, Gerlt and Richard, 2010).

5. Other Enzymes

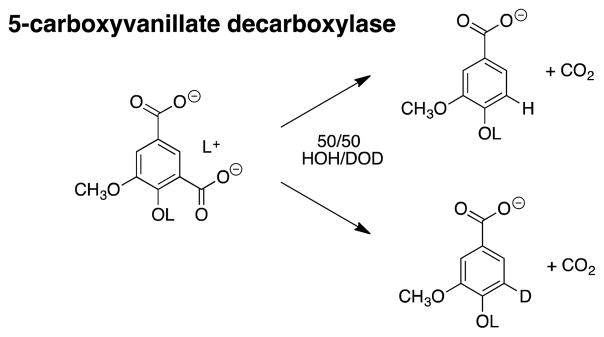

The general protocol described here is suitable for the determination of the PDIE for any enzyme-catalyzed or nonenzymatic decarboxylation, and was recently applied in a study on the mechanism of the decarboxylation of 5-carboxyvanillate catalyzed by 5-carboxyvanillate decarboxylase (CVDB). This enzyme shows SDIEs on kcat and kcat/Km of 2.9 and 2.0 respectively, and a PDIE of 4.6 that was determined as the ratio of -H and -D labelled products formed in a solvent of 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD (Scheme 6) (Vladimirova, et al., 2016). The observation of a substantial kinetic SDIE for separate experiments in HOH and DOD, and of a PDIE for experiments in the mixed HOH/DOD solvents provide strong evidence that the rate and product determining steps for CVDB-catalyzed decarboxylation are the same. The authors of this work provide strong support for the stepwise mechanism shown in Scheme 7, where effectively irreversible and rate determining hydron transfer to form a cyclohexadiene reaction intermediate is followed by rapid loss of CO2 (Vladimirova, Patskovsky, Fedorov, Bonanno, Fedorov, Toro, Hillerich, Seidel, Richards, Almo and Raushel, 2016).

Scheme 6.

The products of 5-carboxyvanillate decarboxylase catalyzed reactions of 5-carboxyvanillate in 50/50 (v/v) HOH/DOD.

Scheme 7.

The stepwise mechanism for the decarboxylation of 5-carboxyvanillate catalyzed by CVDB, where the rate-determining step is protonation of the substrate to form a cyclohexadiene intermediate.

Scheme 2.

The hydrolysis of a ring-substituted styrene in a mixed solvent to give a mixture of -H and -D labeled substituted acetophenones. The primary isotope effect on hydron transfer is calculated from the ratio of the yields of -H and -D labelled reaction products using eq 1, as described below.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the US National Institutes of Health Grants GM116921 and GM039754 for generous support of our work.

References

- Amyes TL, Richard JP. Determination of the pK(a), of ethyl acetate: Bronsted correlation for deprotonation of a simple oxygen ester in aqueous solution. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1996;118(13):3129–3141. [Google Scholar]

- Amyes TL, Richard JP. Generation and stability of a simple thiol ester enolate in aqueous solution. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1992;114(26):10297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Amyes TL, Wood BM, Chan K, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Formation and Stability of a Vinyl Carbanion at the Active Site of Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: pKa of the C-6 Proton of Enzyme-Bound UMP. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130(5):1574–1575. doi: 10.1021/ja710384t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleby TC, Kinsland C, Begley TP, Ealick SE. The crystal structure and mechanism of orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, USA. 2000;97(5):2005–2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.259441296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett SA, Amyes TL, McKay Wood B, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Activation of R235A Mutant Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase by the Guanidinium Cation: Effective Molarity of the Cationic Side Chain of Arg-235. Biochemistry. 2010;49(5):824–826. doi: 10.1021/bi902174q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett SA, Amyes TL, Wood BM, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Dissecting the Total Transition State Stabilization Provided by Amino Acid Side Chains at Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: A Two-Part Substrate Approach. Biochemistry. 2008;47(30):7785–7787. doi: 10.1021/bi800939k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley TP, Appleby TC, Ealick SE. The structural basis for the remarkable catalytic proficiency of orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2000;10(6):711–718. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley TP, Ealick SE. Enzymatic reactions involving novel mechanisms of carbanion stabilization. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2004;8(5):508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TK, Chiang Y, Guo HX, Kresge AJ, Mathew L, Powell MF, Wells JA. Solvent Isotope Effects in H2O-D2O Mixtures (Proton Inventories) on Serine-Protease-Catalyzed Hydrolysis Reactions. Influence of Oxyanion Hole Interactions and Medium Effects. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1996;118(37):8802–8807. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich JI, Hwang C-C, Cook PF, Blanchard JS. Evidence for a Stepwise Mechanism of OMP Decarboxylase. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1999;121(29):6966–6967. [Google Scholar]

- Jarret RM, Saunders M. Use of various nuclei as probes in a new NMR method for obtaining proton/deuteron fractionation data. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1986;108(24):7549–7553. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks WP. Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology. Dover Publications; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kresge AJ. Solvent isotope effects and the mechanism of chymotrypsin action. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1973;95(9):3065–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kresge AJ, More O’Ferrall RA, Powell MF. Solvent Isotope Effects, Fractionation Factors and Mechanisms of Proton Transfer Reactions. In: Buncel E, editor. Isotopes in Organic Chemistry. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1987. pp. 178–275. [Google Scholar]

- Kresge AJ, Sagatys DS, Chen HL. Vinyl ether hydrolysis. 9. Isotope effects on proton transfer from the hydronium ion. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1977;99(22):7228–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo DJ, O’Connell EL, Rose IA. Physical, chemical, and enzymological characterization of enolpyruvate. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101(17):5025–30. [Google Scholar]

- Macciantelli D, Seconi G, Eaborn C. Further Studies of Solvent Isotope Effects in the Cleavage of Substituted Benzyltrimethylsilanes by Methanolic Sodium Methoxide. Intermediate Kinetic Isotope Effects for Reactions of Carbanions with Methanol. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2. 1978:834–838. [Google Scholar]

- Massoud SS, Sigel H. Metal ion coordinating properties of pyrimidine-nucleoside 5′-monophosphates (CMP, UMP, TMP) and of simple phosphate monoesters, including D-ribose 5′-monophosphate. Establishment of relations between complex stability and phosphate basicity. Inorganic Chemistry. 1988;27(8):1447–1453. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BG, Hassell AM, Wolfenden R, Milburn MV, Short SA. Anatomy of a proficient enzyme: the structure of orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase in the presence and absence of a potential transition state analog. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, USA. 2000;97(5):2011–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030409797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BG, Wolfenden R. Catalytic proficiency: the unusual case of OMP decarboxylase. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2002;71:847–885. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard JP. The biochemistry of enols. Wiley; 1990. The chemistry of enols; pp. 651–89. [Google Scholar]

- Richard JP, Amyes TL, Lin S-S, ACMO’Donoghue MMT, Tsuji Y, Williams KB. How Does Organic Structure Determine Organic Reactivity? Partitioning of Carbocations Between Addition of Nucleophiles and Deprotonation. Advances in Physical Organic Chemistry. 2000;35:67–115. [Google Scholar]

- Richard JP, Williams KB. A Marcus Treatment of Rate Constants for Protonation of Ring-Substituted α-Methoxystyrenes: Intrinsic Reaction Barriers and the Shape of the Reaction Coordinate. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129(21):6952–6961. doi: 10.1021/ja071007k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard JP, Williams KB, Amyes TL. Intrinsic Barriers for the Reactions of an Oxocarbenium Ion in Water. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1999;121(36):8403–8404. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JL, Rose IA. Proton transfer reactions of muscle pyruvate kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1972;247(4):1096–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schowen KB, Schowen RL. Solvent isotope effects on enzyme systems. Methods in Enzymology. 1982;87:551–606. (Enzyme Kinet. Mech., Pt. C) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schowen RL. Mechanistic deductions from solvent isotope effects. Progress in Physical Organic Chemistry. 1972;9:275–332. [Google Scholar]

- Schowen RL. The use of solvent isotope effects in the pursuit of enzyme mechanisms. J Labelled Compd Radiopharm. 2007;50(11–12):1052–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Toth K, Amyes TL, Wood BM, Chan K, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Product Deuterium Isotope Effect for Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Evidence for the Existence of a Short-Lived Carbanion Intermediate. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129(43):12946–12947. doi: 10.1021/ja076222f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth K, Amyes TL, Wood BM, Chan K, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Product Deuterium Isotope Effects for Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Effect of Changing Substrate and Enzyme Structure on the Partitioning of the Vinyl Carbanion Reaction Intermediate. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132(20):7018–7024. doi: 10.1021/ja102408k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang W-Y, Richard JP. A Simple Method To Determine Kinetic Deuterium Isotope Effects Provides Evidence that Proton Transfer to Carbon Proceeds over and Not through the Reaction Barrier. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129(34):10330–10331. doi: 10.1021/ja073679g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang W-Y, Richard JP. Structure-Reactivity Effects on Primary Deuterium Isotope Effects on Protonation of Ring-Substituted α-Methoxystyrenes. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131(39):13952–13962. doi: 10.1021/ja905080e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang W-Y, Wood BM, Wong FM, Wu W, Gerlt JA, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Proton Transfer from C-6 of Uridine 5′-Monophosphate Catalyzed by Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Formation and Stability of a Vinyl Carbanion Intermediate and the Effect of a 5-Fluoro Substituent. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012;134(35):14580–14594. doi: 10.1021/ja3058474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirova A, Patskovsky Y, Fedorov AA, Bonanno JB, Fedorov EV, Toro R, Hillerich B, Seidel RD, Richards NGJ, Almo SC, Raushel FM. Substrate Distortion and the Catalytic Reaction Mechanism of 5-Carboxyvanillate Decarboxylase. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2016;138(3):826–836. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westheimer FH. The Magnitude of the Primary Kinetic Isotope Effect for Compounds of Hydrogen and Deuterium. Chemical Reviews. 1961;61:265–273. [Google Scholar]