Abstract

Background

Acute stress may trigger atrial fibrillation (AF), but the underlying mechanisms are unclear. We examined if acute mental stress results in abnormal left atrial electrophysiology as detected by more negative deflection of P-wave terminal force in lead V1 (PTFV1), a well-known marker of AF risk.

Methods and Results

We examined this hypothesis in 422 patients (mean age=56±10 years; 61% men; 44% white) with stable coronary heart disease who underwent mental (speech task) stress testing. PTFV1 was defined as the duration (ms) times the value of the depth (µV) of the downward deflection (terminal portion) of the P-wave in lead V1 measured on digital electrocardiograms (ECG). Electrocardiographic left atrial abnormality was defined as PTFV1 ≤ −4000 µV*ms. Mean PTFV1 values during stress and recovery were compared with rest. The percentage of participants who developed left atrial abnormality during stress and recovery was compared with the percentage at rest. Compared with rest, PTFV1 became more negative during mental stress [mean change= −348, 95%CI=(−515, −182); P<0.001] and no change was observed at recovery [mean change= 12, 95%CI=(−148, 172); P=0.89]. A larger percentage of participants showed left atrial abnormality on ECGs obtained at stress (n=163, 39%) and recovery (n=142, 34%) compared with rest (n=127, 30%).

Conclusion

Acute mental stress alters left atrial electrophysiology, suggesting that stressful situations promote adverse transient electrical changes to provide the necessary substrate for AF.

Keywords: mental stress, left atrial abnormality, electrocardiogram, electrophysiology, arrhythmia

INTRODUCTION

Changes in atrial structure (e.g., atrial remodeling) are thought to precede the development of atrial arrhythmias and provide the necessary substrate for arrhythmia occurrence.1 Accordingly, left atrial abnormalities detected on the 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) have emerged as an area of exploration, as these metrics are thought to represent underlying atrial pathology that predisposes to atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation (AF).2

P-wave terminal force in lead V1 (PTFV1) is easily computed on the routine ECG and defined as the duration (ms) times the value of the depth (µV) of the downward deflection (terminal portion) of the median P-wave in lead V1. Abnormal PTFV1 values detect persons who have underlying left atrial fibrosis, dilation, and elevating filling pressure.2–4 Risk factors for abnormal PTFV1 are similar to AF risk factors (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, and smoking).5 Accordingly, this well-known left atrial abnormality has been associated with an increased risk for the development of AF.5–8 Additionally, PTFV1 is associated with an increased risk for ischemic stroke,5, 9, 10 and the association between PTFV1 and stroke is independent of AF.5 The aforementioned findings highlight the importance of PTFV1 to better characterize AF risk, and possibly identify patients who are high risk for cardiac thromboembolism and/or have subclinical AF.

Mental stress is associated with decreased AV nodal refractoriness and conduction time,11 suggesting a role for mental stress to promote the occurrence of atrial arrhythmias. This is supported by studies that have implicated psychological stress as a risk factor for AF.12–15 However, studies have not examined the influence of mental stress on left atrial electrophysiology, as measured by PTFV1. Therefore, we hypothesized that acute mental stress results in more negative deflection of PTFV1, a well-known marker of left atrial electrophysiology. Such a finding would further support a link between acute mental stress and AF. Furthermore, it would suggest that the evaluation of left atrial abnormality on the routine ECG in persons during acute stress may help characterize at-risk populations for stress-induced AF.

METHODS

Study Population

Patients who had high-quality digital ECGs from the Mental Stress and Myocardial Ischemia After Myocardial Infarction: Sex Differences and Mechanisms (MIMS) study and the Mental Stress Ischemia Mechanisms and Prognosis Study (MIPS) were included in this analysis.16, 17 Both studies examined mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) with identical assessment measures, but with different study goals. MIMS examined sex differences in mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia in 300 patients 60 years of age or younger with myocardial infarction (MI) within 8 months of enrollment. MIPS examined the prognosis and underlying mechanisms of mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia in 695 patients aged 30–80 years with known stable CHD. Study participants underwent two one-day single-photon emission computed tomography imaging studies (one with mental stress and one with exercise or pharmacological stress) within one week of each other; the order of the two sessions was balanced. The day prior to stress testing, either mental stress or physiological, anti-ischemic medications (e.g., beta-blockers, long-acting nitrates) were withheld. The study protocol was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent at the time of enrollment. This analysis included a total of 422 participants who had good quality digital ECG assessments performed during mental stress testing.

Mental Stress Procedure

Details of the protocol used to induce mental stress in each study participant have been previously described.17, 18 Study participants were asked to perform a standardized public speaking task to induce mental stress after 30 minutes of rest. Each subject was asked to imagine a real-world situation in which a close relative was being mistreated in a nursing home. Subsequently, they were asked to make up a realistic story of this scenario and given 2 minutes to prepare a speech. They were then given 3 minutes to recite this speech in front of a video camera and an audience wearing white coats. Detailed physiological response data, including blood pressure, heart rate, and ECGs, were obtained at rest, during stress, and during recovery.

ECG Measurements

Ten-second 12-lead digital ECGs were obtained at 25 mm/s paper speed by trained technicians with GE MAC 5000 electrocardiographs using standardized procedures. ECGs were obtained at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz and 32 bits per sample. All filters in the ECG machines were disabled to provide unfiltered measurements. ECGs were transmitted electronically to a core laboratory at the Epidemiological Cardiology Research Center (Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) in partnership with Emory University. Transmission was without data compression. ECGs were automatically processed, after visual inspection for technical errors and inadequate quality, using the 2001 version of the GE Marquette 12-SL program (GE, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA). As part of routine quality control measures regarding ECG data processing, trained staff performed visual inspection of main ECG waveforms and confirmed computer-detected ECG abnormalities.

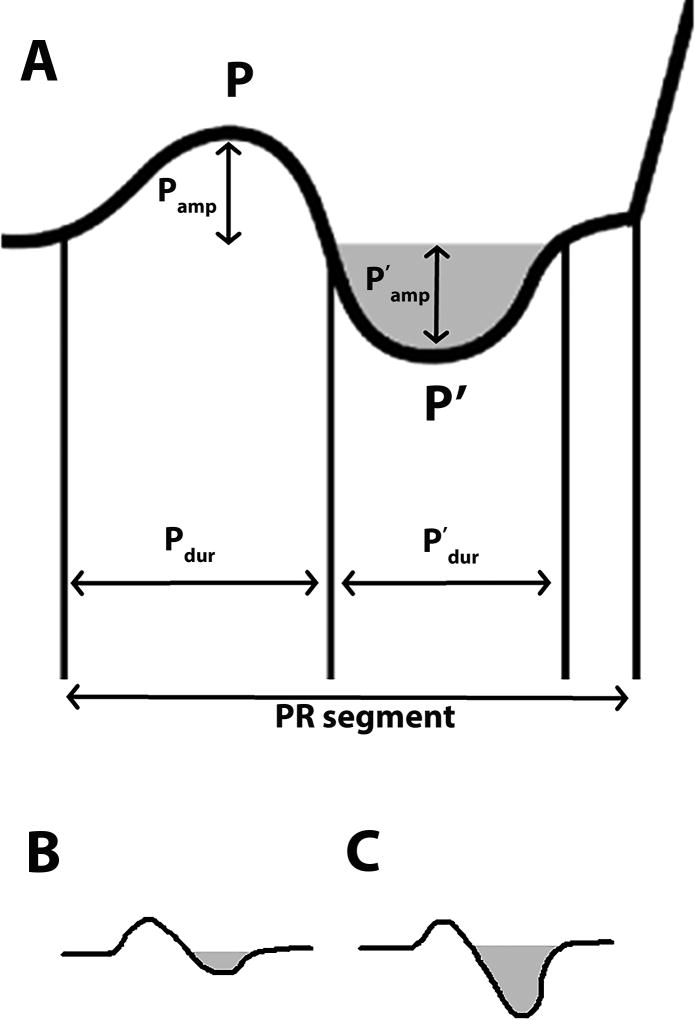

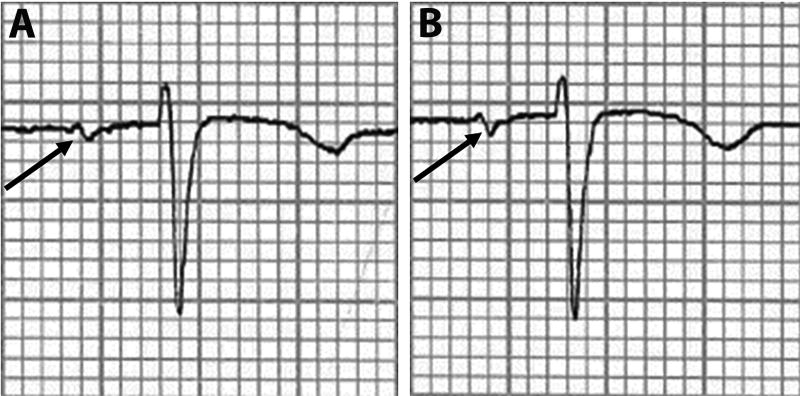

Digital 12-lead ECG tracings were obtained after 30 minutes of relaxation (rest), 2 minutes after starting the speech stress, and 5 minutes after the speech (recovery). The ECG leads remained attached during the entire protocol to preserve comparability between tracings. PTFV1 was defined as the duration (ms) times the value of the depth (µV) of the downward deflection (terminal portion) of the median P-wave in lead V1, and this measure was automatically measured in each ECG (Figure 1). The waveforms required to compute PTFV1 were P’dur and P’amp, and these parameters were automatically measured from the study ECGs using the GE Marquette 12-L program (GE Marquette, Milwaukee, WI). These digital waveform measurements have a time resolution of approximately 2 ms and an amplitude resolution of approximately 5 µV.19 PTFV1 was measured on the baseline, stress, and recovery ECGs. An example of the negative deflection observed during stress compared with a baseline ECG is shown in Figure 2. Left atrial abnormality was defined as PTFV1 values ≤ −4000 µV*ms, as this cut-off point has been linked to several adverse cardiovascular events.5, 7, 20 The ascertainment of left atrial abnormality based on the automated measures used in this analysis has been shown to have a 94% agreement rate when compared with manual scoring.5

Figure 1. Schematic of PTFV1 Measurement.

PTFV1 was defined as the value of the amplitude (P’amp) multiplied by the duration (P’dur) of the terminal portion of the P-wave (P’; shaded area) in lead V1 of a standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (A). A normal PTFV1 is shown in (B), while (C) demonstrates an abnormally increased PTFV1 with deeper downward (more negative) deflection.

PTFV1=P-wave terminal force in lead V1.

Figure 2. Example of Rest (A) and Stress (B) PTFV1 Measurements.

PTFV1 is shown for example rest (A) and stress (B) ECG tracings. As shown, the defection of the terminal portion of the P-wave in lead V1 is more negative in stress (B) compared with rest (A).

PTFV1=P-wave terminal force in lead V1.

Patient Characteristics

Detailed characteristics, including demographic information, anthropometric measurements, medical history, and medication history, for each patient included in this study were obtained by a research nurse. Age, gender, race, smoking history, household income, and educational attainment were self-reported. Smoking was defined as the current or former use of cigarettes. Household income was dichotomized at $20,000. Education as dichotomized at “high school or less” versus “some college or more”. Diabetes and hyperlipidemia were defined by self-report and also verified by medical record review. Resting blood pressure was obtained for each participant during the resting phase of stress testing, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure values were used in this study. Similarly, heart rate was obtained by pulse assessment. Body mass index was defined as the weight in kilograms divided by the height in meters squared. The use of cardiovascular medications (e.g., statins, aspirin, beta blockers, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors) was self-reported and verified by the research nurse. Prior MI and heart failure were defined by self-reported history and medical record review that indicated clinically apparent conditions were present in the past and not at the time of mental stress testing. Heart failure was categorized as present independent of ejection fraction (e.g., reduced versus preserved). Severity of coronary artery disease was assessed by the Gensini score.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared by the presence of left atrial abnormality (PTFV1 values ≤ −4000 µV*ms) on the resting ECG. Categorical data were compared using the Chi-square test, and the Student’s t-test was used for continuous data. The baseline characteristics also were stratified by original study participation (MIMS vs. MIPS). Mean PTFV1 values were computed during the rest, stress, and recovery periods for the entire cohort. The mean values of PTFV1 during stress and recovery were compared with rest values using the Student’s t-test (H0: change in PTFV1 = 0). Additionally, the percentages of participants who had left atrial abnormality during stress and recovery were compared with those at rest. A secondary analysis that excluded participants with baseline left atrial abnormality was performed to determine if the change in PTFV1 was dependent on the presence of this abnormality at baseline. We also examined if the change in PTFV1 during stress and recovery was dependent on hemodynamic response (change in heart rate and blood pressure) using a linear regression model adjusted for age, sex, race, baseline PTFV1, and original study participation (MIMS vs. MIPS). A similar linear regression model was used to determine if change in PTFV1 during stress was dependent on baseline characteristics (age, sex, race, diabetes, smoking, body mass index, prior MI, heart failure, physical-induced myocardial ischemia, mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia). A secondary analysis also was performed for change in PTFV1 by study participation (MIMS vs. MIPS). Statistical significance was defined as α = 0.05 and SAS® version 9.4 (SAS® Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Of the 422 patients (mean age=56 ± 10 years; 61% men; 44% white) participants, 233 (55%) were from the MIMS cohort and 189 (45%) from the MIPS cohort. A total of 127 (30%) had left atrial abnormality at rest. The baseline characteristics for the entire sample, and for those with and without left atrial abnormality at rest, are shown in Table 1. The baseline characteristics stratified by original study participation are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (N=422)

| Characteristic | All Participants (N=422) |

LAA at Rest* | P-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Yes (n=127) |

No (n=295) |

|||

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 56 ± 10 | 59 ± 10 | 55 ± 10 | 0.0014 |

| Male (%) | 259 (61) | 85 (69) | 174 (59) | 0.12 |

| White (%) | 185 (44) | 52 (41) | 133 (45) | 0.43 |

| Ever smoker (%) | 168 (40) | 59 (46) | 109 (37) | 0.067 |

| Income, <$20,000 (%) | 108 (26) | 34 (27) | 74 (25) | 0.72 |

| Education, high school or less (%) | 86 (20) | 26 (20) | 60 (20) | 0.98 |

| Diabetes (%) | 140 (33) | 49 (39) | 91 (31) | 0.12 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 291 (69) | 89 (70) | 202 (68) | 0.74 |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 31 ± 6.7 | 31 ± 6.2 | 31 ± 7.0 | 0.99 |

| Statin (%) | 357 (85) | 104 (82) | 253 (86) | 0.31 |

| Aspirin (%) | 342 (81) | 107 (84) | 235 (80) | 0.27 |

| Beta blockers (%) | 344 (82) | 102 (80) | 242 (82) | 0.68 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (%) | 278 (66) | 91 (72) | 187 (63) | 0.10 |

| Myocardial infarction (%) | 104 (25) | 33 (26) | 71 (24) | 0.68 |

| Heart failure (%) | 48 (11) | 17 (13) | 31 (11) | 0.39 |

| Gensini Score (%) | 44 ± 50 | 52 ± 51 | 40 ± 49 | 0.034 |

| Rest heart rate, mean ± SD, bpm | 65 ± 11 | 67 ± 12 | 65 ± 11 | 0.091 |

| Speech heart rate, mean ± SD, bpm | 80 ± 17 | 81 ± 17 | 79 ± 16 | 0.32 |

| Recovery heart rate, mean ± SD, bpm | 67 ± 12 | 68 ± 12 | 66 ± 11 | 0.093 |

| Rest systolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 135 ± 20 | 138 ± 19 | 134 ± 20 | 0.083 |

| Speech systolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 159 ± 26 | 163 ± 26 | 157 ± 26 | 0.059 |

| Recovery systolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 140 ± 21 | 144 ± 21 | 138 ± 21 | 0.010 |

LAA defined as PTFV1 values ≤ −4000 µV*ms.

Statistical significance for categorical data was tested using the Chi-square test and for continuous data the Student’s t-test was used.

LAA=left atrial abnormality.

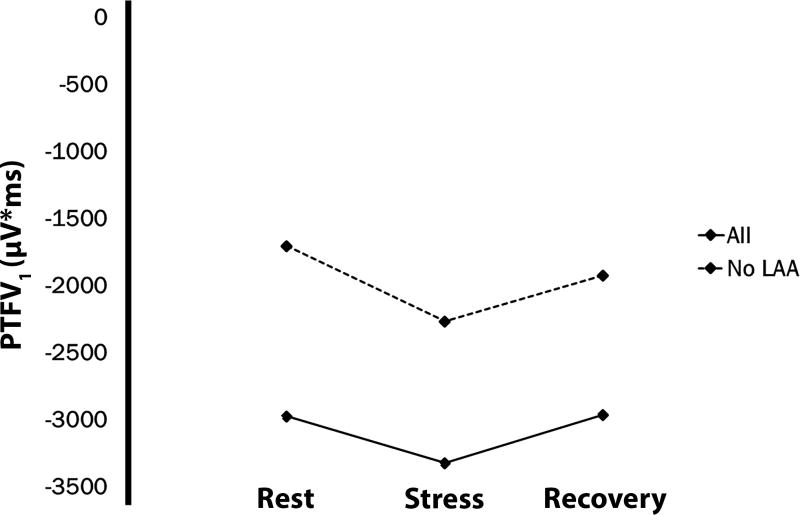

The mean PTFV1 at rest was −2973 ± 2478 µV*ms. Compared with the ECG obtained during rest, PTFV1 became more negative with stress [mean change = −348, 95%CI= (−515, −182); P<0.001]. No difference was observed between rest and recovery tracings [mean change = 12, 95%CI= (−148, 172); P=0.89] (Table 2). The mean change in PTFV1 is depicted in Figure 3. The change in PTFV1 was not dependent on heart rate or blood pressure responses during stress or in recovery, and these data are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

Table 2.

Change in PTFV1 with Mental Stress*

| Measurement | PTFV1 Mean ± SD |

Difference from Rest Mean (95%CI) |

P-value | LAA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N=422) | ||||

| Rest | −2973 ± 2478 | - | - | 127 (30) |

| Stress | −3322 ± 2609 | −348 (−515, −182) | <0.001 | 163 (39) |

| Recovery | −2962 ± 2530 | 12 (−148, 172) | 0.89 | 142 (34) |

| Baseline LAA Excluded (N=295) | ||||

| Rest | −1703 ± 1479 | - | - | - |

| Stress | −2267 ± 1988 | −564 (−769, −360) | <0.001 | 55 (19) |

| Recovery | −1923 ± 1844 | −220 (−410, −31) | 0.023 | 41 (14) |

LAA defined as PTFV1 values ≤ −4000 µV*ms.

CI=confidence interval; PTFV1=P-wave terminal force in lead V1; LAA=left atrial abnormality; SD=standard deviation.

Figure 3. Change in Mean PTFV1 during Acute Mental Stress.

PTFV1=P-wave terminal force in lead V1.

A larger percentage of participants showed left atrial abnormality on ECGs obtained during stress (n=163, 39%) and recovery (n=142, 34%) compared with rest (Table 2). When we excluded participants with baseline left atrial abnormality (n=127), PTFV1 was more negative with stress [mean change = −564, 95%CI= (−769, −360); P<0.001] and during recovery [mean change = −220, 95%CI= (−410, −31); P=0.023) compared with rest (Table 2). Additionally, 67 (23%) patients developed a new left atrial abnormality who did not have a baseline abnormality.

When we examined baseline characteristics associated with PTFV1 change during stress (Table 3), female sex was associated with a more negative mean change (−381 µV*ms in PTFV1; P=0.032) compared with men. A history of heart failure was also associated with a more negative mean change (−715 µV*ms in PTFV1; P=0.0058) than those without heart failure. Other characteristics examined were not associated with PTFV1 change during stress. Similar changes in PTFV1 were observed in both MIMS and MIPS participants (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of PTFV1 Change with Stress (N=422)

| Characteristic | β-coefficient* | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10-year increase) | −39 | 0.71 |

| Female | −381 | 0.032 |

| White | 57 | 0.76 |

| Diabetes | 282 | 0.32 |

| Smoking | −283 | 0.11 |

| Body mass index (per 5-unit increase) | 73 | 0.24 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | −59 | 0.76 |

| Heart failure | −715 | 0.0058 |

| Physical stress ischemia | −264 | 0.15 |

| Mental stress ischemia | −32 | 0.88 |

β-coefficient represents the mean change in PTFV1 during stress associated with each characteristic. Linear regression model adjusted for age, sex, race, baseline PTFV1, and original study participation.

CI=confidence interval; PTFV1=P-wave terminal force in lead V1; SD=standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this analysis provide evidence that acute mental stress results in adverse changes in PTFV1 and the development of left atrial abnormality on the 12-lead ECG in persons with CHD. Women and patients with heart failure were more susceptible to these adverse changes. Overall, these data suggest that acute mental stress transiently alters left atrial electrophysiology, and possibly promotes adverse electrical atrial remodeling.

Several reports have implicated PTFV1 in the pathogenesis of AF.5–8 The likely link between PTFV1 and this common arrhythmia is the detection of abnormal atrial remodeling that provides the necessary substrate for AF, as more negative PTFV1 represents underlying left atrial fibrosis, dilation, and elevated filling pressure.2–4 However, to our knowledge, prior reports have not examined if acute changes in PTFV1 are possible. Additionally, we are the first to provide evidence that acute mental stress results in more negative deflection of PTFV1 and the development of left atrial abnormality. Potentially, repeated exposure to mental stress results in enduring atrial remodeling, providing the pro-arrhythmic substrate necessary for AF. This is supported by the fact that more negative deflection of PTFV1 is associated with AF,5–8 and several reports have linked psychological stress to an increased risk of AF.12–15

The pathophysiology that links mental stress with abnormal left atrial electrophysiology is unknown. Decreased AV nodal refractoriness and conduction time have been observed with exposure to acute mental stress.11 Therefore, the findings of the current study possibly are related to differences in autonomic tone, as parasympathetic blockade reduces P-wave duration.21 Additionally, women and patients with heart failure were more likely to experience adverse changes in PTFV1 during mental stress. Women are more susceptible to mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia than men,16 and this condition possibly plays a role to influence PTFV1 in women who are exposed to mental stress. Heart failure patients also have increased left atrial remodeling and stiffness, and this presumably is due to higher left ventricular filling pressure and backflow across the mitral valve.22 Therefore, it is possible that higher left atrial filling pressures explain the more negative deflection of PTFV1 with mental stress, as increases in left atrial volumes correlate with abnormal PTFV1.3 Furthermore, we observed a more pronounced decrease in PTFV1 after excluding those with baseline left atrial abnormality (mean change in PTFV1: −564 vs. −348). This possibly is due to the fact that those with abnormal PTFV1 values have a lowered responsiveness to autonomic tone.23 Although we offer several explanations for the observed findings, the exact mechanisms are unknown and further research is needed to explain our findings.

Recent data have supported a role for psychological stress as a risk factor for AF.12, 13, 15 Data from the Framingham Offspring Study have implicated tension, anger, and hostility as risk factors for AF in males.12, 13 Additionally, persons with AF have higher levels of self-reported perceived stress than those without the arrhythmia.15 Furthermore, negative emotions have been shown to trigger symptomatic AF in patients who have a history of the arrhythmia.14 Despite numerous studies that have established several risk factors for AF, the pathophysiology that predisposes patients to its development in stressful situations has yet to be fully elucidated. This analysis provides evidence that acute mental stress alters left atrial electrophysiology and provides a pathophysiological link for the findings of prior reports.

Our findings provide initial evidence for potentially reversible biomarkers of AF risk on the routine ECG, which may allow for the better characterization of at-risk populations for stress-induced AF. Additionally, the role of psychological stress as a risk factor for AF, and subclinical ECG markers for its development, represent a novel area of research that possibly will improve our understanding of the pathogenesis of this arrhythmia. Furthermore, interventions that are able to reduce stress and its effects on left atrial electrophysiology may play a role in the prevention of AF and its complications.

This study should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. All patients included in this study had documented evidence of CHD at the time of study enrollment. CHD is a well-known risk factor for AF,24 and it is possible that similar changes in PTFV1 will not be observed for patients who do not have underlying atherosclerosis. Change in PTFV1 was measured with mental stress testing, and further study is needed to determine if such changes occur with standard physical stress testing (e.g., exercise or pharmacological). We were unable to determine the underlying mechanisms that link acute mental stress with changes in PTFV1 and further research is needed to understand our findings. Specifically, change in PTFV1 with mental stress possibly is related to left atrial size or diastolic parameters obtained on routine echocardiographic assessment. We were unable to explore if the observed findings were related to these anatomic parameters as detailed echocardiograms were not obtained in the cohort examined. Additionally, we were unable to link changes in PTFV1 during acute mental stress with AF development, as the occurrence of AF was not a primary endpoint of the MIMS or MIPS studies. Nonetheless, this study is the first to demonstrate that changes in PTFV1 during acute mental stress occur, and future studies are needed to link these changes with clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, this analysis provides evidence that acute mental stress promotes adverse changes in left atrial electrophysiology, as measured by PTFV1 on the 12-lead ECG. Further research is needed to determine the underlying mechanisms that explain our findings, and also to determine if these changes result in an increased risk for AF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under the following award numbers: P01HL101398, R01HL109413, R01HL109413-02S1, K24HL077506, K24MH076955, UL1TR000454, KL2TR000455, and F32HL134290. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Iwasaki YK, Nishida K, Kato T, Nattel S. Atrial fibrillation pathophysiology: implications for management. Circulation. 2011;124:2264–2274. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.019893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, Okin P, Kligfield P, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Childers R, Gorgels A, Josephson M, Kors JA, Macfarlane P, Mason JW, Pahlm O, Rautaharju PM, Surawicz B, van Herpen G, Wagner GS, Wellens H American Heart Association E, Arrhythmias Committee CoCC, American College of Cardiology F, Heart Rhythm S: AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:992–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tiffany Win T, Ambale Venkatesh B, Volpe GJ, Mewton N, Rizzi P, Sharma RK, Strauss DG, Lima JA, Tereshchenko LG. Associations of electrocardiographic P-wave characteristics with left atrial function, and diffuse left ventricular fibrosis defined by cardiac magnetic resonance: The PRIMERI Study. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasser I, Kennedy JW. The relationship of increased left atrial volume and pressure to abnormal P waves on the electrocardiogram. Circulation. 1969;39:339–343. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.39.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamel H, O'Neal WT, Okin PM, Loehr LR, Alonso A, Soliman EZ. Electrocardiographic Left Atrial Abnormality and Stroke Subtype in ARIC. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:670–678. doi: 10.1002/ana.24482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ, Case LD, Zhang ZM, Goff DC., Jr Ethnic distribution of ECG predictors of atrial fibrillation and its impact on understanding the ethnic distribution of ischemic stroke in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Stroke. 2009;40:1204–1211. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.534735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eranti A, Aro AL, Kerola T, Anttonen O, Rissanen HA, Tikkanen JT, Junttila MJ, Kentta TV, Knekt P, Huikuri HV. Prevalence and prognostic significance of abnormal P terminal force in lead V1 of the ECG in the general population. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:1116–1121. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magnani JW, Zhu L, Lopez F, Pencina MJ, Agarwal SK, Soliman EZ, Benjamin EJ, Alonso A. P-wave indices and atrial fibrillation: cross-cohort assessments from the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J. 2015;169:53–61. e51. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamel H, Soliman EZ, Heckbert SR, Kronmal RA, Longstreth WT, Jr, Nazarian S, Okin PM. P-wave morphology and the risk of incident ischemic stroke in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2014;45:2786–2788. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamel H, Bartz TM, Longstreth WT, Jr, Okin PM, Thacker EL, Patton KK, Stein PK, Gottesman RF, Heckbert SR, Kronmal RA, Elkind MS, Soliman EZ. Association between left atrial abnormality on ECG and vascular brain injury on MRI in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 2015;46:711–716. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Insulander P, Vallin H. Gender differences in electrophysiologic effects of mental stress and autonomic tone inhibition: a study in health individuals. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:59–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2005.04117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaker ED, Sullivan LM, Kelly-Hayes M, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Benjamin EJ. Anger and hostility predict the development of atrial fibrillation in men in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation. 2004;109:1267–1271. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118535.15205.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaker ED, Sullivan LM, Kelly-Hayes M, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Benjamin EJ. Tension and anxiety and the prediction of the 10-year incidence of coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and total mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:692–696. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000174050.87193.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lampert R, Jamner L, Burg M, Dziura J, Brandt C, Liu H, Li F, Donovan T, Soufer R. Triggering of symptomatic atrial fibrillation by negative emotion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1533–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Neal WT, Qureshi W, Judd SE, Glasser SP, Ghazi L, Pulley L, Howard VJ, Howard G, Soliman EZ. Perceived Stress and Atrial Fibrillation: The REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49:802–808. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9715-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaccarino V, Shah AJ, Rooks C, Ibeanu I, Nye JA, Pimple P, Salerno A, D'Marco L, Karohl C, Bremner JD, Raggi P. Sex differences in mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia in young survivors of an acute myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:171–180. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammadah M, Al Mheid I, Wilmot K, Ramadan R, Shah AJ, Sun Y, Pearce B, Garcia EV, Kutner M, Bremner JD, Esteves F, Raggi P, Sheps DS, Vaccarino V, Quyyumi AA. The Mental Stress Ischemia Prognosis Study: Objectives, Study Design, and Prevalence of Inducible Ischemia. Psychosom Med. 2017;79:311–317. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sagie A, Larson MG, Goldberg RJ, Bengtson JR, Levy D. An improved method for adjusting the QT interval for heart rate (the Framingham Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:797–801. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90562-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kligfield P, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Childers R, Deal BJ, Hancock EW, van Herpen G, Kors JA, Macfarlane P, Mirvis DM, Pahlm O, Rautaharju P, Wagner GS, American Heart Association E, Arrhythmias Committee CoCC, American College of Cardiology F, Heart Rhythm S. Josephson M, Mason JW, Okin P, Surawicz B, Wellens H. Recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part I: The electrocardiogram and its technology: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation. 2007;115:1306–1324. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okin PM, Kamel H, Kjeldsen SE, Devereux RB. Electrocardiographic left atrial abnormalities and risk of incident stroke in hypertensive patients with electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1831–1837. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheema AN, Ahmed MW, Kadish AH, Goldberger JJ. Effects of autonomic stimulation and blockade on signal-averaged P wave duration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:497–502. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)80028-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melenovsky V, Hwang SJ, Redfield MM, Zakeri R, Lin G, Borlaug BA. Left atrial remodeling and function in advanced heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:295–303. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah AJ, Lampert R, Goldberg J, Veledar E, Bremner JD, Vaccarino V. Posttraumatic stress disorder and impaired autonomic modulation in male twins. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271:840–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.