Abstract

Controlling the exchange of genetic information between sexually reproducing populations has applications in agriculture, eradication of disease vectors, control of invasive species, and the safe study of emerging biotechnology applications. Here we introduce an approach to engineer a genetic barrier to sexual reproduction between otherwise compatible populations. Programmable transcription factors drive lethal gene expression in hybrid offspring following undesired mating events. As a proof of concept, we target the ACT1 promoter of the model organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a dCas9-based transcriptional activator. Lethal overexpression of actin results from mating this engineered strain with a strain containing the wild-type ACT1 promoter.

Genetic isolation of a genetically modified organism represents a useful strategy for biocontainment. Here the authors use dCas9-VP64-driven gene expression to construct a ‘species-like’ barrier to reproduction between two otherwise compatible populations.

Introduction

Engineering barriers to sexual reproduction between otherwise compatible organisms has numerous potential applications. Specific examples include preventing herbicide resistance genes from moving from cultivated to weedy plant varieties1, generating new mating incompatibilities to control pest populations, and for the safe study of gene-drives2. These applications could be achieved by engineering a speciation event, with speciation defined as reproductive isolating mechanisms that prevent genetic exchange between newly formed taxa3, 4.

Ideally, the introduction of species-like barriers would result in an engineered organism that behaves and can be propagated in an identical fashion to its non-modified counterpart. Changing the genetic code has been proposed as a means to accomplish this. Genetic recoding has been successful in Escherichia coli 5, 6 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae may soon follow7, 8. However, we are not likely to recode higher organisms with ease in the near future. Knocking down a copy of haploinsufficient genes has been used to generate hybrid depression9, 10, but not lethality. There are a handful of other examples of engineering genetic incompatibility in the literature. Chromosomal translocations that generate compound autosomes produce Drosophila melanogaster genetically incompatible with the wild-type, but these suffer from poor zygote viability11. A “synthetic species” of D. melanogaster 12 was developed by knocking out the glass transcription factor, and integrating a glass dependent killing module which is activated when mated with wild-type flies. Mating insects infected with different strains of Wolbachia bacteria can also result in embryonic lethality13. These approaches are either only applicable to a small number of species and/or dramatically change the engineered organism’s phenotype.

Several other forms of genetic incompatibility are in development or use for the control of pest species. These are mostly based on sterile insect technique which functions by releasing radiation or chemical sterilized males to find and non-productively mate with wild-type females14. For many insect species, Wolbachia infected males are incompatible with uninfected females; however, infected females are compatible with uninfected males so that sorting females from males must be highly efficient13, 15. Conditional lethal gene constructs exist which allow for the rearing of organisms under laboratory setting in the presence of a small molecule repressor. Offspring between released adult males and wild-type females are non-viable due to the absence of the small molecule. This approach has been successfully applied to the mosquito Aedes aegypti by the biotechnology company Oxitec16. A variation to this approach utilizes a conditional lethal gene that only kills female offspring17 which is in development for insect pests18 as well as invasive vertebrates species19.

These approaches will not doubt be valuable to controlling disease vector populations, however, unless the target species is driven to extinction, continuous release will be necessary to prevent reintroduction which may be prohibitively expensive in some settings. Population replacement strategies that result in disease resistant organisms occupying the vector’s niche20, 21 may be desirable in these cases. If the replacement population has been engineered to be disease resistant22, then it should ideally be incapable of reproducing with the wild-population to maintain the resistant genotype. Wolbachia infected mosquitoes are resistant to some arbovirus infections23, 24, but research is needed to determine if they may boost risk of other infections25. Combining engineered resistance with Wolbachia infection is an option, however, these strains would still be able to reproduce with the disease-vectoring population since Wolbachia infected females are usually capable of mating with uninfected males.

Multiple transgene biocontainment approaches have been explored beyond physical and/or temporal separation in plants including cleistogamy, maternal inheritance, gametic transgene excision, synthetic auxotrophy, and total sterility. However, each of these strategies has at least one major drawback that prevents wide-spread adoption. Cleistogamy, in which flowers never open and therefore must self-pollinate is not applicable to all species26. Cleistogamy may be possible to engineer in rice27 but it precludes the use of yield boosting hybrid seeds28, 29. Maternal inheritance of transgenes by plastid engineering is likewise not applicable to all species and pollen-mediated transfer of plastids at low frequencies may be common in many species30. The excision of a transgene from a pollen-expressed recombinase is highly efficienct31, however, control of recombinase activity interferes with normal propagation. Total sterility requires asexual propagation and is therefore not practical for many species. Any approach which uses additional chemical inputs to regulate lethal genes requires changes to normal cultivation techniques. Genome reprogramming to confer metabolic dependence on synthetic compounds6 is not yet possible in plants due to the large scale of genetic changes required. Furthermore, with the exceptions of cleistogamy and asexual propagation, these methods only prevent outward gene-flow. This is an important consideration since the unwanted flow of genes into genetically engineered plants can alter desirable traits.

Here we describe a broadly applicable approach to engineer species-like barriers to sexual reproduction. This method interrupts sexual reproduction between populations of different genotypes with minimal effects on growth and reproduction. Further, propagation of the engineered organisms does not require the use of exogenous inputs32. This technology may enable more scalable means for the containment of transgenic organisms, and provide additional tools to disrupt disease vector populations either through population reduction or replacement strategies.

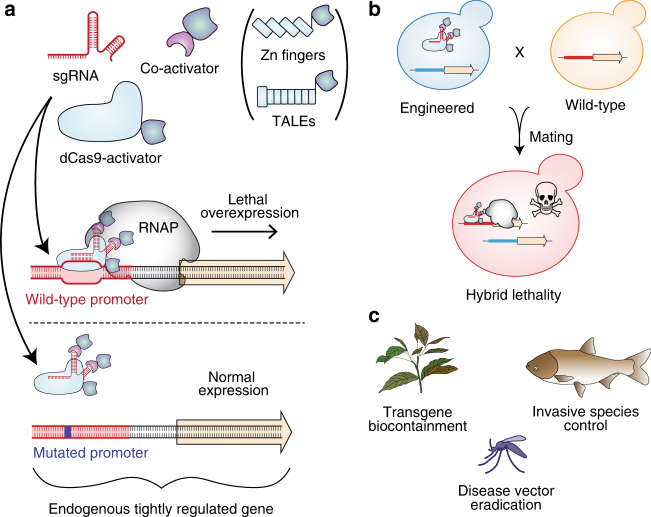

In our approach, synthetic species-like genetic barriers are introduced via a relatively simple system (Fig. 1a–c) that utilizes programmable transcriptional activators (PTAs) capable of lethal overexpression of endogenous genes. Lethality in the engineered strain is prevented by refactoring the target locus, allowing the programmable activator to be expressed in the engineered strain. This activator serves as a sentinel for undesired mating events. Hybridization between the synthetically incompatible (SI) strain and an organism containing the transcriptional activator’s target sequence results in lethal gene expression (Fig. 1b). Because programmable transcription activators have been shown to work in many organisms33–38, this technology could be expected to readily transfer to higher organisms including plants39, insects33, and vertebrates40 (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Overview of synthetic incompatibility. a Macromolecular components that constitute programmable transcription factors (above), and schematic illustration showing lethal gene expression from a wild-type but not a refactored promoter (below). b Illustration of hybrid lethality upon mating of wild-type (orange cell) and SI (green cell) parents. Macromolecular components are labeled in a, red DNA signifies WT promoter, and blue DNA signifies refactored promoter. Skull and crossbones indicates a non-viable genotype. c Possible applications for engineered speciation

We demonstrate a proof of concept for SI in the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We introduce a mutation in the actin promoter and then engineer this yeast to express a PTA targeting the wild-type version of the actin promoter. Mating the engineered strain to the wild-type causes overexpression of actin and lysis of the hybrid cells.

Results

Targeting promoters for lethal overexpression

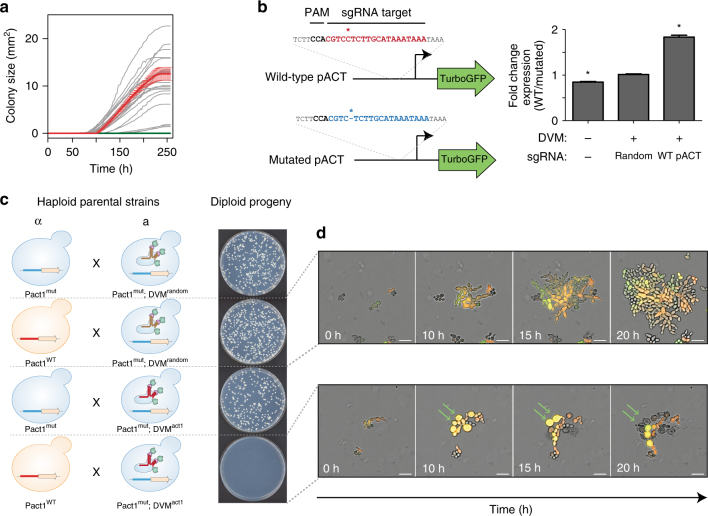

We demonstrate our approach in S. cerevisiae using a programmable transcriptional activation system composed of dCas9-VP64 combined with single-guide RNA (sgRNA) aptamer binding MS2-VP64 (referred hereafter as DVM) which is based on previously demonstrated strong activators38, 41. Appropriate target genes were identified empirically by using the DVM system to activate promoters of genes whose overexpression is reported to generate an ‘inviable’ phenotype in the Saccharomyces Genome Database42 (Supplementary Table 1). We designed sgRNAs to bind unique sequences immediately upstream of NGG protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sites in a ~400 bp window upstream of predicted transcriptional start sites43 of candidate genes. Transformant growth rates were then measured for ~10.5 days. We identified several target sites which generated severely reduced growth rates and a single ACT1 target which generated no growth (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 1). Additional screening for targets that generated no growth identified three more sites in the ACT1 promoter and one combination of two guides targeting the TUB2 promoter (Supplementary Fig. 1). For further analysis, we selected a target site on the bottom strand 300 nucleotides upstream of the ACT1 transcriptional start site. The nine PAM distal nucleotides are predicted to be Forkhead transcription factor binding sites44.

Fig. 2.

Engineering speciation by synthetic incompatibility. a Growth curves of yeast expressing DVM targeted to promoter regions of SI candidate genes. Random sgRNA control shown in red. Best ACT1 targeting sgRNA in green. All others in gray. (n = 2 transformations, mean ± SEM, error bars omitted for gray lines for clarity). b (Left) Diagram of mutated and wild-type ACT1 promoter-GFP constructs. (Right) GFP expression ratios with or without DVM and/or ACT1 promoter specific sgRNA. (*p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test, n = 3 independent cultures, mean ± SEM). c (Left) Schematic representation of SI components present in haploid strain crosses and (right) the resulting diploid colonies. Results representative of three independent replicates. d Live-cell imaging time lapse of diploid cells from crossing RFP+ MATα with GFP+ Mata cells in a compatible (Top) and incompatible (Bottom) mating. Green arrows indicate cells which swell and lyse. The experiment was repeated twice. 20 µm scale bar

Engineering SI strain

To generate a SI strain, we used Cas945 to introduce a mutation by non-homologous end joining in the ACT1 promoter. The mutated promoter differs from wild-type by a single cytosine deletion 3 bp upstream of the PAM site. There is no observable growth phenotype resulting from the mutated ACT1 promoter (Supplementary Fig. 2). We characterized transcription from the mutated promoter by expressing TurboGFP46 under the control of the wild-type or mutated ACT1 promoters in the presence or absence of DVM (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3). There was a slight increase in TurboGFP expression from the mutated promoter in the absence of DVM. However, no change was found with a non-targeting sgRNA. TurboGFP expression was 1.8-fold higher from the wild-type ACT1 promoter than the mutated promoter when DVM was guided by a sgRNA targeting the wild-type promoter. Together, these results indicate that the mutation in the ACT1 promoter does not substantially change native expression but prevents targeted transcriptional activation by DVM guided to the wild-type sequence. We completed construction of the SI strain by chromosomally integrating a DVM targeted to the wild-type ACT1 promoter sequence in the strain containing the mutated ACT1 promoter (i.e., Fig. 1b).

Next, we examined the genetic compatibility between the SI strain and a strain with the wild-type ACT1 promoter. S. cerevisiae has haploid mating types MATa and MATα, and can be propagated as a haploid of either mating type or as a diploid after mating. We mated haploid strains with different auxotrophic markers and selected for diploids to determine mating efficiency (Fig. 2c). Mating a MATa strain with the SI genotype but a random sequence sgRNA to a MATα strain also containing the mutated ACT1 promoter resulted in numerous diploid colonies (Fig. 2c). This shows that expression of the DVM machinery or mutation of the ACT1 promoter do not prevent sexual reproduction. This same MATa strain was also successfully mated to a MATα strain carrying the wild-type ACT1 promoter (Fig. 2c), as the random sequence sgRNA does not induce lethal overexpression of ACT1. We were also able to cross the MATa strain with a complete SI genotype to a MATα strain with the mutated ACT1 promoter and obtain viable diploids (Fig. 2c). However, when the SI MATa strain was mated with a MATα strain containing the wild-type ACT1 promoter, diploid colonies were seen only in low frequencies (Fig. 2c). This failed mating reflects the genetic incompatibility of the SI genotype with wild-type.

In order to understand how the concentrations of actin protein compared between conditions, we performed mating experiments and measured phalloidin stained F-actin content of diploid cells with flow cytometry. Diploid yeast resulting from non-permissive mating have 9.3-fold more F-actin than is present in diploids from permissive mating (Supplementary Fig. 4). This discrepancy from the modest 1.8-fold increase of promoter activity seen above suggests that the rate of actin degradation may not be increased to match the increase in synthesis.

We further investigated the genetic incompatibility using live-cell imaging (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Movie 1). Diploid yeast resulting from a permissive mating (Fig. 2c) are able to proliferate and produce a microcolony after 20 h (Fig. 2d, top). Diploids arising from the non-permissive mating of wild-type ACT1 promoter yeast with the SI strain undergo a limited number of divisions before swelling and eventually lysing (Fig. 2d, bottom). These results are consistent with what we expect from uncontrolled cytoskeletal growth. However, the ability for these yeast to divide a few times before lysis may also provide opportunities for recombination and escape.

Analysis of escape mechanisms

We next turned our attention to the colonies occasionally found when mating the SI strain to the wild-type. These colonies appeared at a frequency of 4.83 × 10−3 compared to mating with a compatible strain. Sanger sequencing the ACT1 promotor found that most (3/5) originated from a cell homozygous for the mutated version of the promoter, suggesting that recombination had taken place between homologous chromosomes. Richardson et al.47 reported single-strand oligonucleotide homology directed repair frequencies of 7 × 10−3 in the presence of dCas9 in mammalian cell culture. Therefore, a similar mechanism may be responsible for the apparent mitotic gene conversion observed here. A fourth colony had a mutated MS2-VP64 activator and we were unable to locate mutations in the remaining colony.

Yeast is a useful system for demonstrating the molecular proof of concept for SI, however, there are challenges that will need to be addressed for applications in higher organisms. Identifying target genes that can be lethally overexpressed using PTAs is crucial. Since developing animal embryos are sensitive to concentration gradients of morphogens for proper body pattern formation, they have been found to be lethal when ectopically expressed48–51 and are likely to be ideal targets for SI. Indeed, Lin et al.33 demonstrated that dCas9-VPR can robustly activate several D. melanogaster morphogenic genes in vitro as well as cause embryonic lethality when targeted to the promoter of wingless and driving ectopic expression. Likewise, targeting genes that affect plant morphogenesis or immune response also holds promise for SI52–54. Transitioning SI to higher organisms will likely require high-throughput in vitro assays to identify PTA targets that are suitable for strong activation of candidate genes followed by in vivo tests for organismal lethality.

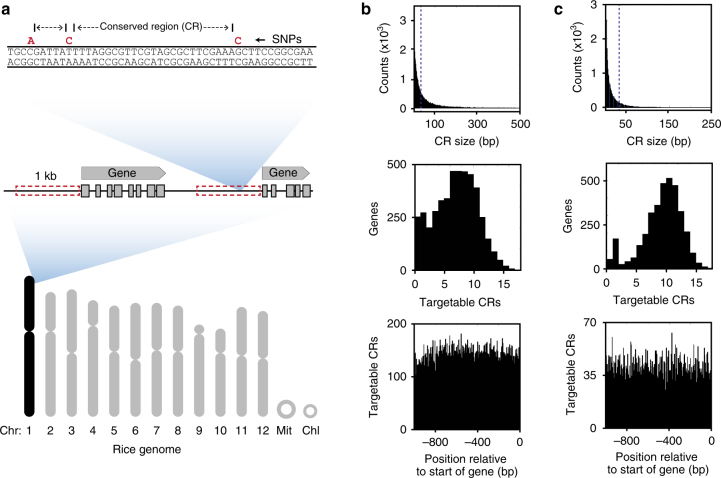

A possible pitfall to applying SI would be the presence of genetic polymorphisms at the target site that prevent PTA binding and therefore escape. Therefore, invasive species which underwent a recent genetic bottleneck55, 56 would pose less of a challenge than transgene containment between an engineered crop and a ubiquitous conspecific weed. We analyzed the promoter regions of rice (Oryza sativa) and D. melanogaster, both of which contain a substantial amount of variation57, 58. Our goal was to determine the frequency of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-free sequences in promoter regions which could potentially serve as dCas9-target sites using our speciation approach. An analysis was performed of promoter SNPs within chromosome 1 comparing the Nipponbare reference to all 45 US cultivars and land races available in the rice 3k SNP database57 (Fig. 3a, b). Despite substantial variation, there is an average of 6.5 SNP-free sequences per promoter region that are large enough to be targeted by a PTA (Fig. 3b). Likewise, an analysis of SNP data from 205 inbred wild strains of D. melanogaster collected from a food market in Raleigh, NC59 found an average of 8.8 SNP-free regions larger than 30 bp within 1 kb upstream of annotated genes from chromosome 2L (Fig. 3c). These targetable sequences are present with equal frequency throughout the 1 kb region upstream of annotated genes (Fig. 3b, c, bottom panel), allowing freedom to design diverse targeting sgRNAs.

Fig. 3.

Promoter sequence diversity analysis in rice and fruit flies. a Schematic represenation of rice chromosome with illustration of SNP-free conserved region (CR) identification. Red box denotes 1 kb upstream of annotated genes from Chr1 in the Oryza sativa Nipponbare genome. b Number of conserved regions versus size is shown for all SNP-free conserved sequences in promoter regions of Chr1 (top, n = 65,500 CRs). Also shown are targetable CRs (defined as those larger than 30 bp) per promoter region (middle, n = 4487 genes), and the relative position of these targetable sequences relative to the start of the annotated gene (’0’) (bottom). c Equivalent data as in b, but for chromosome 2L from Drosophila melanogaster. (Total CRs in top panel = 215,705, total genes in middle panel = 3486). Spike at x = 1 for middle histograms is partially due to the counting of SNP-less promoters (entire 1 kb with no SNPs) as having a single CR

Lastly, we have shown that a PTA can be linked to a positive selection module to ensure that it is expressed in the target organism. We replaced the promoter of a kanamycin selectable marker with a nucleotide sequence containing the PTA target site from pACT1 followed by a minimal promoter. Growth of yeast in the presence of kanamycin required expression of the same PTA used for engineering SI (Supplementary Fig. 5). Similar constructs linking the expression of an essential or selectable gene (e.g., herbicide resistance) may improve the robustness of SI.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have presented the proof of concept for a, to the best of our knowledge, new approach to introducing defined genetic barriers to sexual reproduction. Synthetic incompatibility requires a single, phenotypically-neutral genomic edit, and the expression of a transcriptional activator targeting the unedited locus. Recently developed CRISPR-Cas9 based technologies should make it possible to apply synthetic incompatibility in a broad variety of sexually reproductive organisms. Recombination events between the target and mutant loci likely triggered by dCas9 binding indicate that applying this technology in higher organisms will require expressing dCas9 activators only in multicellular stages of life so that it is unlikely enough cells undergo recombination to rescue the whole organism. The period of transcriptional quiescence for the first cellular divisions in animal zygotes60 may therefore facilitate SI’s application.

Applying synthetic incompatibility to crops engineered to make biofuels or pharmaceuticals may allow for broader cultivation while preventing transgene flow to wild relatives or varieties used for human consumption. Synthetic incompatibility may also find applications in biocontrol of pest organisms by releasing SI males to reduce the fecundity of wild populations. As a form of lethal underdominance, synthetic species-like barriers hold promise as an approach to confine gene-drive systems and as a method to replace disease-vectoring populations of insects with non-vectoring insects10, 61.

Methods

Plasmids

Plasmid sequences can be found in GenBank with accession numbers listed in Supplementary Table 2 and primer sequences in Supplementary Data 1. Plasmid maps are found in Supplementary Fig. 6 and descriptions in Supplementary Table 2.

Strains and media

Detailed information for all yeast strains can be found in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 7. Yeast transformations were performed using the Lithium-acetate method62. Overnight liquid cultures were diluted to ~0.5 OD600 in 2X yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium and grown to ~2.0 OD600. The cells were then washed and mixed with DNA, lithium acetate, and salmon sperm carrier DNA and incubated at 42 °C for 40 min. The cells were then pelleted and plated onto dropout media or allowed 3–3.5 h of outgrowth in 2X YPD prior to plating onto G418 Sulfate selection. Chemically competent E. coli STBL3 (Thermo Fisher) was used for all plasmid cloning and propagation in LB media (MP) supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Yeast were grown at 28–30 °C on plates or in liquid culture with 250 rpm agitation. Yeast were cultured in YPD (10 g/l yeast extract, 20 g/l peptone, 20 g/l dextrose), 2X YPD, or synthetic dropout (SD) media (1.7 g/l yeast nitrogenous base, 5 g/l ammonium sulfate, yeast SD media supplements (Sigma), 20 g/l dextrose). G418 sulfate resistant yeast were selected on YPD agar with 300–400 µg/ml G418 Sulfate. Counterselection for KlURA3 was performed using 1 g/l 5-Floroorotic acid.

Screening candidate genes

Screening target genes was performed by transforming yeast strain YMM124 with pMM2-20-1 backbone vectors expressing sgRNA to candidate genes (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Transformations were plated onto SD-Ura in 6-well plates and incubated at 30 °C. To calculate growth rates of colonies on petri dishes63, 64, we scanned colonies as they grew using Epson Perfection V19 scanners in two hour intervals for 256 h. We used image analysis to track the areas of colonies as they grew. This entailed converting Red-Green-Blue (RGB) scans into Hue-Saturation-Value (HSV) colorspace, selecting the V channel, performing a background subtraction, smoothing, and using a threshold to identify biomass. The V channel was selected because it had the highest contrast with the background. The background was the first image in a time-lapse, before any colonies appeared. We smoothed images twice with a fine-grain Gaussian filter (sd = 1 pixel, filter width = 7 pixels) to remove noise. We used a single threshold for all images for consistency. Colony centers were identified by applying regional peak detection to a z-projection through time using the thresholded images. When colonies merged, we used these peaks to find the dividing line between colonies: the peaks were used as seeds in a watershed on a distance-transformed image. Once colony boundaries were identified, the number of “on” pixels within a boundary at each moment in time was counted as the colony’s area. We did not include in the analysis colonies which fell along the edge of the petri dish, which merged with colonies along the edge, or which had an ambiguous number of peaks within a large merged region. To calculate growth rates, we log-transformed the area-over-time data and fit a line in a 12 h moving window. The maximum slope in each time series was recorded as that colony’s growth rate. The growth rates were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test to compare each condition to the random sgRNA control.

Growth rate comparison

We inoculated 2 ml YPD with CEN.PK or YMM127 and placed them in a 30 °C shaker. After ~24 h, we inoculated 199 µl of YPD with 1 µl of culture in a clear, flat-bottom 96-well plate (Costar). Two technical replicates were included for each overnight culture. Plates were incubated at 30 °C in an Epoch 2 plate reader (BioTek) for 16 h with continuous shaking. The OD600 was measured every 10 min. Background subtracted OD measurements were plotted on a semilog graph and the slope was calculated from the linear portion of the graph (between 210 min and 330 min).

Plate based mate assay

Haploid MATa yeast strain YMM134 and YMM155 were mated to MATα strains YMM125 and YMM141 by combining overnight cultures in YPD to an OD600 of 0.1 each in 1 ml YPD. The cultures were then incubated at 30 °C for 4 hours, washed once with water and 30 µl were plated onto SD-Ura/Leu dropout media.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry for promoter analysis was performed using yeast strains YMM158 through YMM163. YMM158, YMM160, and YMM162 expressed TurboGFP driven by the wild-type ACT1 promoter from plasmid pMM2-17-1. YMM159, YMM161, and YMM163 contained pMM2-17-2 and expressed TurboGPF from a mutated ACT1 promoter. Overnight cultures grown in 2 ml SD-Complete media were diluted to an OD600 = 0.5 and grown for an additional four hours. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed with DPBS, resuspended in DPBS, and placed on ice protected from light prior to analysis. Flow cytometry was performed using a LSRFortessa H0081 cytometer. At least 30,000 TurboGFP positive singlet events were collected per sample. The geometric means of GFP fluorescence intensity were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test for pairwise comparisons.

F-actin content was analyzed by mating yeast strain YMM139 to YMM156 or YMM157 in SD-Trp using an OD600 = 1.0 of each strain. After 6.5 hr the media was replaced with SD-Ura/Leu/Trp for 24 h to select for diploids. Cells were subsequently fixed with 4% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100. F-actin was stained with phalloidin CF647 (Biotium) and then rinsed with PBS. Flow cytometry was performed using a BD FACS LSRII by collecting at least 10,000 events gated on singlet GFP and RFP positive cells and measuring the geometric mean of phalloidin fluorescent intensity then comparing groups by two tailed t-test.

Live-cell imaging

Yeast strain YMM139 was mated separately with YMM156 or YMM157 in SD-Trp dropout media for 2 h, pelleted, and resuspended in SD-Ura/Leu/Trp. Mated yeast were loaded onto a CellASIC ONIX diploid yeast plate and supplemented with SD-Ura/Leu/Trp. Cells were imaged using a Nikon Ti-E Deconvolution Microscope System every 6 min for 20 h.

Verification of yeast genomic mutations

Insertion of the MS2-VP64 cassette in the Lys2 locus was verified by PCR using primers MM_TA_CPCR_F and MM_Kan_CPCR_R which detect the presence of the transgene in the Lys2 locus and MM_TA_CPCR_F and MM_TA_WT_CPCR_R which screen for the wild-type locus. (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Insertion of the sgRNA and dCas9-VP64 cassette into Leu2 locus was verified by PCR using MM_DV_Leu2_CPCR_F and MM_DV_Leu2_CPCR_R which detect the presence of the transgene and MM_WT_Leu2_CPCR_F and MM_DV_Leu2_CPCR_R which detect the wild-type locus (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Mutations in the Act1 promoter were detected by PCR amplifying a portion of the promoter using primers MM_Actg4_CPCR_F and MM_Actg4_CPCR_R. The gel purified amplicon was then Sanger sequenced using the MM_Actg4_CPCR_F primer.

Promoter SNP analysis

All rice cultivars and landraces of US origin from the International Rice Center that were sequenced as part of the 3k SNP database57 (45 total) were analyzed for SNP distribution in promoter regions of Chromosome 1. One kb upstream of each annotated gene in the Nipponbare genome (GenBank) was extracted and searched for SNPs using the 3k SNP database data set. SNP-free regions between these loci, which represent sequences that are absolutely conserved across all genomes examined, were quantified to generate graphs in Fig. 3.

The fly data is from the Drosophila Genome Research Project58, and includes SNPs from 205 inbred wild strains collected from a food market in Raleigh, NC59. Promoter regions from chromosome 2L were used for the analysis of SNPs in a 1 kb region upstream of annotated genes, using the same methods described above for rice.

Positive selection module

Yeast strains YMM130 and YMM131 were transformed with PCR amplicons of the positive selection modules and MS2-VP64 from plasmids pMM2-21-8 and pMM2-21-9 including flanking regions homologous to lys2. Cells were plated onto YPD supplemented with 300 µg/ml G418 to select for lys2 integration events.

Data availability

All data are available from the authors upon request.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

M.M. and M.J.S. are supported by a grant from the University of Minnesota Office of the Vice President of Research and by The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (grant number D17AP00028). The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this article are those of the author and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies, either expressed or implied, of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency or the Department of Defense. S.C.H. and M.J.S. are supported by an award from the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation. J.M.C. is supported by a grant from the Biocatalysis Initiative at the University of Minnesota. Microscopy imaging and analysis was performed at the University Imaging Centers, University of Minnesota. Flow cytometry was performed using University Flow Cytometry Resource services, University of Minnesota.

Author contributions

M.M. conceived of synthetic incompatibility. M.M. and M.J.S. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. M.M. performed the strain engineering, mating experiments, and flow cytometry. S.C.H. performed the plate-based growth assays. J.M.C. and W.R.H. analyzed plate-based growth assay data. M.M., S.C.H., and M.J.S. conceived and performed all other data analysis.

Competing interests

M.M. and M.J.S. have filed patents for the presented technology. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01007-3.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Burgos NR, et al. The impact of herbicide-resistant rice technology on phenotypic diversity and population structure of United States weedy rice. Plant Physiol. 2014;166:1208–1220. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.242719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oye KA, et al. Biotechnology. Regulating gene drives. Science. 2014;345:626–628. doi: 10.1126/science.1254287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayr, E. Systematics and the Origin of Species from the Viewpoint of a Zoologist. (Columbia Univ. Press, New York, 1942).

- 4.Turelli M, Barton NH, Coyne JA. Theory and speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001;16:330–343. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lajoie MJ, et al. Genomically recoded organisms expand biological functions. Science. 2013;342:357–360. doi: 10.1126/science.1241459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rovner AJ, et al. Recoded organisms engineered to depend on synthetic amino acids. Nature. 2015;518:89–93. doi: 10.1038/nature14095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annaluru N, et al. Total synthesis of a functional designer eukaryotic chromosome. Science. 2014;344:55–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1249252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boeke JD, et al. GENOME ENGINEERING. The Genome Project-Write. Science. 2016;353:126–127. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed FA. First steps towards underdominant genetic transformation of insect populations. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e97557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis S, Bax N, Grewe P. Engineered underdominance allows efficient and economical introgression of traits into pest populations. J. Theor. Biol. 2001;212:83–98. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novitski E, Grace D, Strommen C. The entire compound autosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1981;98:257–273. doi: 10.1093/genetics/98.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno E, et al. Design and construction of ‘synthetic species’. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zabalou S, et al. Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility as a means for insect pest population control. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15042–15045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403853101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alphey L, et al. Sterile-insect methods for control of mosquito-borne diseases:an analysis. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:295–311. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Zhu C, Zhang D. Naturally occurring incompatibilities between different culex pipiens pallens populations as the basis of potential mosquito control measures. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013;7:e2030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris AF, et al. Field performance of engineered male mosquitoes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:1034–1037. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinrich JC, Scott MJ. A repressible female-specific lethal genetic system for making transgenic insect strains suitable for a sterile-release program. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:8229–8232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140142697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black WC, Alphey L, James AA. Why RIDL is not SIT. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thresher R, et al. Sex-ratio-biasing constructs for the control of invasive lower vertebrates. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robert MA, et al. A reduce and replace strategy for suppressing vector-borne diseases: insights from a deterministic model. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boëte C, Agusto FB, Reeves RG. Impact of mating behaviour on the success of malaria control through a single inundative release of transgenic mosquitoes. J. Theor. Biol. 2014;347:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabrieli P, Smidler A, Catteruccia F. Engineering the control of mosquito-borne infectious diseases. Genome Biol. 2014;15:535. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0535-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aliota MT, Peinado SA, Velez ID, Osorio JE. The wMel strain of Wolbachia Reduces Transmission of Zika virus by Aedes aegypti. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28792. doi: 10.1038/srep28792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohanty I, Rath A, Mahapatra N, Hazra RK. Wolbachia: a biological control strategy against arboviral diseases. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2016;53:199–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodson BL, et al. Wolbachia enhances West Nile virus (WNV) infection in the mosquito Culex tarsalis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8:e2965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hüsken A, Prescher S, Schiemann J. Evaluating biological containment strategies for pollen-mediated gene flow. Environ. Biosafety Res. 2010;9:67–73. doi: 10.1051/ebr/2010009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshida H, et al. superwoman1-cleistogamy, a hopeful allele for gene containment in GM rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2007;5:835–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Virmani, S. (ed.) Hybrid Rice Technology: New Developments and Future Prospects: Selected Papers from the International Rice Research Conference. (International Rice Research Institute, Manilla, 1994).

- 29.Deliberto, M. & Salassi, M. Hybrid Rice Production Costs and Returns: Comparisons with Conventional Clearfield Varieties 1–8 (LSU AgCenter Staff Report, 010).

- 30.Murphy DJ. Improving containment strategies in biopharming. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2007;5:555–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo K, et al. ‘GM-gene-deletor’: Fused loxP-FRT recognition sequences dramatically improve the efficiency of FLP or CRE recombinase on transgene excision from pollen and seed of tobacco plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2007;5:263–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2006.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas DD, et al. Insect population control using a dominant, repressible, lethal genetic system. Science. 2000;287:2474–2476. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5462.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin S, Ewen-Campen B, Ni X, Housden BE, Perrimon N. In vivo transcriptional activation using CRISPR/Cas9 in Drosophila. Genetics. 2015;201:433–442. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.181065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowder LG, et al. A CRISPR/Cas9 toolbox for multiplexed plant genome editing and transcriptional regulation. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:971–985. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chavez A, et al. Comparison of Cas9 activators in multiple species. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:563–567. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao X, et al. Comparison of TALE designer transcription factors and the CRISPR/dCas9 in regulation of gene expression by targeting enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e155. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bikard D, et al. Programmable repression and activation of bacterial gene expression using an engineered CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:7429–7437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zalatan JG, et al. Engineering complex synthetic transcriptional programs with CRISPR RNA scaffolds. Cell. 2014;160:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim CY, Bove J, Assmann SM. Overexpression of wound-responsive RNA-binding proteins induces leaf senescence and hypersensitive-like cell death. New Phytol. 2008;180:57–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nathans J, et al. A new secreted protein that binds to Wnt proteins and inhibits their activites. Nature. 1999;398:431–436. doi: 10.1038/18899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Konermann S, et al. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature. 2014;517:583–588. doi: 10.1038/nature14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cherry JM, et al. Saccharomyces Genome Database: the genomics resource of budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D700–D705. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Z, Dietrich FS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005. Mapping of transcription start sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using 5’ SAGE; pp. 2838–2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teixeira MC, et al. The YEASTRACT database: an upgraded information system for the analysis of gene and genomic transcription regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D161–D166. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bao Z, et al. Homology-integrated CRISPR-Cas (HI-CRISPR) system for one-step multigene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Synth. Biol. 2015;4:585–594. doi: 10.1021/sb500255k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evdokimov AG, et al. Structural basis for the fast maturation of Arthropoda green fluorescent protein. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:1006–1012. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richardson CD, Ray GJ, DeWitt MA, Curie GL, Corn JE. Enhancing homology-directed genome editing by catalytically active and inactive CRISPR-Cas9 using asymmetric donor DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:339–344. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grether ME, Abrams JM, Agapite J, White K, Steller H. The head involution defective gene of Drosophila melanogaster functions in programmed cell death. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1694–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tseng A-SK, Hariharan IK. An overexpression screen in Drosophila for genes that restrict growth or cell-cycle progression in the developing eye. Genetics. 2002;162:229–243. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rørth P. A modular misexpression screen in Drosophila detecting tissue-specific phenotypes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12418–12422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poole SJ, Kornberg TB. Modifying expression of the engrailed gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 1988;104:85–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.104.Supplement.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sakamoto T. Ectopic expression of KNOTTED1-like homeobox protein induces expression of cytokinin biosynthesis genes in rice. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:54–62. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.085811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaneda T, et al. The transcription factor OsNAC4 is a key positive regulator of plant hypersensitive cell death. EMBO J. 2009;28:926–936. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalyna M, Lopato S, Barta A. Ectopic expression of atRSZ33 reveals its function in splicing and causes pleiotropic changes in development. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:3565–3577. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Golani D, et al. Genetic bottlenecks and successful biological invasions: the case of a recent Lessepsian migrant. Biol. Lett. 2007;3:541–545. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puillandre N, et al. Genetic bottleneck in invasive species: the potato tuber moth adds to the list. Biol. Invasions. 2008;10:319–333. doi: 10.1007/s10530-007-9132-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alexandrov N, et al. SNP-Seek database of SNPs derived from 3000 rice genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D1023–D1027. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.FlyBase Consortium, T. F. The FlyBase database of the Drosophila genome projects and community literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:106–108. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, F. et al. FlyVar: a database for genetic variation in Drosophila melanogaster. Database. 2015, bav079 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Langley AR, Smith JC, Stemple DL, Harvey SA. New insights into the maternal to zygotic transition. Development. 2014;141:3834–3841. doi: 10.1242/dev.102368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marshall JM, Hay BA. Confinement of gene drive systems to local populations: a comparative analysis. J. Theor. Biol. 2012;294:153–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gietz RD, Woods RA. Yeast transformation by the LiAc/SS Carrier DNA/PEG method. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006;313:107–120. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-958-3:107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guillier L, Pardon P, Augustin J-C. Automated image analysis of bacterial colony growth as a tool to study individual lag time distributions of immobilized cells. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2006;65:324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baryshnikova A, et al. Quantitative analysis of fitness and genetic interactions in yeast on a genome scale. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:1017–1024. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the authors upon request.