Abstract

Nonintubated procedures have widely developed during the last years, thus nowadays major anatomical resections are performed in spontaneously breathing patients in some centers. In an attempt for combining less invasive surgical approaches with less aggressive anesthesia, nonintubated uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) lobectomies and segmentectomies have been proved feasible and safe, but there are no comparative trials and the evidence is still poor. A program in nonintubated uniportal major surgery should be started in highly experienced units, overcoming first a learning period performing minor procedures and a training program for the management of potential crisis situations when operating on these patients. A multidisciplinary approach including all the professionals in the operating room (OR), emergency protocols and a comprehensive knowledge of the special physiology of nonintubated surgery are mandatory. Some concerns about regional analgesia, vagal block for cough reflex control and oxygenation techniques, combined with some specific surgical tips can make safer these procedures. Specialists must remember an essential global concept: all the efforts are aimed at decreasing the invasiveness of the whole procedure in order to benefit patients’ intraoperative status and postoperative recovery.

Keywords: Thoracoscopy/video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), lung cancer surgery, anesthesia

Introduction

Nonintubated procedures under spontaneous breathing have become more popular within the last years, although they are still not considered a routine practice in many Thoracic Surgery departments. There are many concerns about indications, technical issues and potential advantages and risks that should be discussed (1).

Most of papers describe unicentric case series and there are some comparative reports, but it seems that the surgical community is mainly focused on technical improvements and new indications rather than searching for standardized criteria and methodology. It is also mandatory to develop a comprehensive analysis in terms of respiratory and hemodynamics parameters, and also in terms of immune response disbalance in order to find out the potential benefits of nonintubated procedures by reducing the surgical invasiveness.

Although initially not considered appropriate for major anatomical resections such as lobectomies or anatomical segmentectomies, a great advance has been made in this field so nowadays these procedures are routinely practiced in several units of Thoracic Surgery and even more complex anatomical resections have been attempted (2,3).

Main challenges while facing major resections under spontaneous breathing are the need for a stable mediastinum, the control of cough reflex by vagal block, the balance of sedation and the duration of the surgery to avoid respiratory depression and severe hypercapnia.

Reasons why and historical perspective

Major anatomical resections (segmentectomies, lobectomies, bilobectomies, pneumonectomies) have been safely performed using a uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) approach since 2011 through general anesthesia and mechanical ventilation (4-6). The rationale for changing this safe anesthetic management should be performing these procedures under spontaneous breathing in order to decrease surgical invasiveness while preserving safety parameters.

Major anatomical resections are mainly performed in lung cancer patients, who are usually associated to smoking and pulmonary underlying disease such as COPD. Mechanical ventilation can induce barotrauma, atelectrauma, volutrauma and biotrauma, and muscle relaxation let abdominal organs to protrude inside the non-operating hemithorax thus decreasing the respiratory functional capacity (RFC) and favoring atelectasis in the dependent lung, ending in a disbalance between ventilation and perfusion (favored during lateral decubitus) and increasing physiologic shunt (7).

Thoracic procedures under spontaneous breathing can avoid these complications of the standard anesthetic management. Using different devices for oxygen supplementation (facial mask, oropharyngeal cannula) minimizes the risk of hypoxemia, while anesthesiologist has to face with moderate hypercapnia due to the “re-breathing” phenomenon (8). Avoiding orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation reduces in-operating room time thus increasing occupation ratio of the operating room (OR). Patients also recover faster without sore throat, and there are some reports that point out a decrease in postoperative complications (9).

Main challenges of these procedures are related to cough reflex, mediastinal movement and the fine adjustment of sedation to avoid respiratory depression.

A systematic search was performed in PubMed using combinations of the terms: “nonintubated”, “awake”, “uniportal”, “uniportal VATS”, “single-port” and “single-incision VATS”. First report of a nonintubated uniportal VATS anatomical resection was published by Gonzalez-Rivas in 2014 with a right-middle lobectomy plus lymphadenectomy (10), followed by an anterior right-upper lobe anatomical segmentectomy via the same approach, reported by Hung also in 2014 (11). Some sporadic reports by the same and other teams have been reported since then (12-14). The unique case series analysis was reported in 2015 by Hung (15), with 116 patients operated through nonintubated uniportal VATS, including 7 anatomical segmentectomies and 2 lobectomies through this approach. They reported no conversion to thoracotomy, and only one conversion to general anesthesia and orotracheal intubation due to mediastinal movement. Some other editorials and review articles have been published with considerations about technical aspects and potential benefits of these procedures (16-18), although there is a lack of comparative and randomized trials between nonintubated uniportal VATS compared to intubated uniportal VATS or nonintubated multiport VATS in order to elucidate the benefits or disadvantages of combining uniportal surgery with minimally invasive anesthesia. It is necessary to highlight that in 3 years there hasn’t been any attempt for reporting comparative trials, what gives an idea that this approach is only being performed in highly experienced centers, mainly in Asia and Europe.

Starting point

Before embarking a nonintubated program for anatomical resections, a learning curve operating minor procedures is mandatory, in order to develop skills for all the members of the multidisciplinary team, and to achieve a comprehensive knowledge of the physiology of surgical pneumothorax in a spontaneously breathing patient.

Pulmonary biopsies, metastatectomies and pneumothorax should first be attempted to find out the main difficulties and the possible solutions (7,19). Primary spontaneous pneumothorax patients are usually young and healthy patients with preserved cough reflex, so surgeons can safely manage the first attempts of vagal block and test the outcomes.

Uniportal experience of the surgeon is relevant as uniportal VATS anatomical resections defy the surgical capability to operate on a less stable mediastinal/surgical field. It is advisable to begin nonintubated uniportal major resections with highly experienced surgeons, able to manage intraoperative complications (i.e., major bleedings) and complex procedures such as sleeve lobectomies in order to achieve abilities such as primary sutures for a potential bleeding (18).

It is also recommended that the anesthesiologists develop first a lateral decubitus orotracheal intubation learning curve (Figure 1) and simulations of emergent intubation in an experimental model (20).

Figure 1.

Position of the patient during lateral decubitus intubation: neutral position, using a couple of surgical pillows and an occipital support to prevent the head going backwards during the laryngoscopy.

The nursing team should be integrated in the essential details of the whole procedure and the management of critical potential situations. They must know their exact role in the different steps of the procedure, and it is important to make them be part of the success of developing these complex resections.

The objective of these programs should focus on decreasing global invasiveness of the surgical procedure preserving the safety, decreasing postoperative complications and improving the antitumoral immune profile.

Selection criteria

There are no standardized selection criteria for nonintubated uniportal VATS procedures, although several teams have reported their algorithms. Despite the initial reports of the team from Rome (Italy) with severe emphysematous patients, most surgical teams that have experienced with nonintubated anatomical resections have globally selected a propitious profile of population: non-obese patients without severe comorbidities neither pulmonary underlying disease with early stage lung cancer, metastatic or benign disease (21-23).

In our nonintubated program initiated on 2013 we set the inclusion and exclusion criteria for these procedures as described in Tables 1 and 2 (20).

Table 1. Inclusion criteria for nonintubated uniportal VATS anatomical resections.

| Inclusion criteria |

| Age ≥18 years-old |

| DLCO >30% |

| ppoFEV1 >30% |

| Baseline PaO2 >60 mmHg |

| ASA ≤3 |

| Signed written informed consent |

DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiology, VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Table 2. Exclusion criteria are mainly based on anatomic features of the patient or pathological conditions that preclude the surgery under spontaneous breathing.

| Exclusion criteria |

| Unfavourable anatomy |

| BMI >30 |

| Narrow thorax |

| Expected difficult airway |

| Prominent superior incisors |

| Impossibility of occluding the superior lip with the inferior incisors |

| Mouth opening less than 3 cm |

| Mallampati >2 |

| Arquate or tight palate |

| Rigid, indurated or non-elastic maxillar space |

| Thyroid-to-chin distance less than 6 cm |

| Short or wide neck |

| Abnormal cervical flexo-extension |

| Previous surgery in cervical/thoracic spine |

| Previous ipsilateral thoracotomy (not previous VATS) |

| Uncontrolled gastroesophageal regurgitation |

| Haemodynamically unstable patient |

| Pleural adhesions in more than 50% of pleural surface |

| Coagulation disorders |

| Clinical stage cT4 lung cancer |

| Induction radiotherapy |

BMI, body mass index.

We initially consider patients above 18 years old without prohibitive pulmonary function tests and low-moderate anesthesia risk scores (ASA ≤3). Main contraindications are obesity, patients with unfavourable anatomy, previous spine surgery or thoracotomy, coagulation disorders or locally advanced lung cancers (cT4), haemodynamically unstable patients or expected extensive pleural adhesions that enlarge surgical time.

These criteria are not absolute and have been developed through achieving experience in nonintubated procedures and visiting other experienced centers such as National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH). They reflect an attempt for including patients for nonintubated uniportal anatomical resections with favorable conditions in terms of anatomy, global health status of the patient and tumor stage but, depending on the center, selection criteria may differ and there are no standardized criteria.

Undoubtedly, patient must be informed and sign an informed consent giving his permission for performing the procedure under nonintubated uniportal VATS instead of the standard general anesthesia.

Ethical aspects

A nonintubated program for major resections should be reviewed and approved by the local Ethics Committee, and a data collection form should be designed for this specific protocol in order to collect all the relevant information. Specific informed consent documents should also be explained and signed at least 24 h before the procedure.

Anesthetic management

The nonintubated VATS (NI-VATS) is a real challenge for the anesthesiologist. Before one decides to start a NI-VATS program one must be friendly with difficult thoracic procedures and specially with lateral decubitus intubation for the management of a potential crisis.

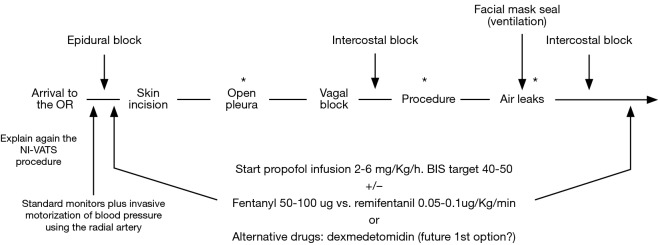

The consecutive phases of anesthesia are shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Flowchart of anesthesia during nonintubated uniportal VATS procedures. OR, operating room; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery. *, arterial gases recommended.

Arrival of the patient to the operation room: the patient must be explained again the nonintubated uniportal VATS procedure, specially about the possibility of feeling some degree of dyspnea in case he/she is not deeply sedated in some part of the procedure;

Standard monitoring including: electrocardiogram, oxygen saturation measured by pulse-oximetry, peripheral venous access, respiratory rate plus invasive blood pressure monitoring using the radial artery (Figure 3). In first cases we used the nasal cannula to monitor CO2 but we found an extremely big difference between the exhaled and arterial CO2 (24). Even in the same patient and depending on the degree of the collapse, the variation wasn’t lineal. For that reason, we decided to take them out from the protocol. The anesthetic depth is monitored through bispectral index (BIS) value, and usually kept between 40 and 60 (14), although some experienced teams report BIS values between 30 and 50. Urinary catheter is placed in some cases, although we have operated many patients through a tubeless approach;

Premedication: Normally we use between 1-3 mg of midazolam and 50-100 µg of fentanyl;

Analgesia: nowadays are used either multiple intercostal blocks at the beginning and the end of the surgery, or epidural block (as in an intubated VATS). We explain later these techniques;

Sedation: this is a matter of discussion, there is not a perfect drug, all of them have secondary effects. In our experience, the use of a propofol infusion (2–4 mg/kg/h) plus the regional block is a good combination. Adding opioids as fentanyl (50–100 µg) is reserved to control the respiratory rate. Remifentanil infusions is associated with severe cases of hypercapnia (PaCO2 >100 mmHg). Dexmedetomidine is a theoretical drug with a better profile: analgesic effects due to alpha2-agonist, lower respiratory depression and preservation of ventilatory response to CO2. Also, it has a biphasic hemodynamic response, resulting in hypotension at low plasma concentrations and hypertension at higher plasma concentrations;

Monitors of respiratory parameters: respiratory rate must be monitored to prevent risk of hypercapnia. If the patient has a low respiratory rate, it is normally associated with deep mediastinal movement (higher surgical difficulties). That is why finding the correct balance between good surgical field and avoiding respiratory depression is sometimes not easy to achieve;

Air leaks test: to facilitate the test of potential air leaks, we use a normal facial mask, sealing it surrounding nose and mouth. With this technique, lung filling and re-expansion is more homogeneous and lets the surgeon test the water-tightness of the lung and bronchial sutures;

Awakening: once the drainage is positioned and the wound is closed, the propofol infusion is stopped so the patient awakes, and is taken to the recovery room, so oral intake and walking begin within the next 6 h.

Figure 3.

Routine monitoring during nonintubated uniportal anatomical resections: electrocardiogram, blood pressure, heart and respiratory rate, pulse-oximetry, bispectral index (BIS) monitoring.

Locoregional anesthesia

Nonintubated uniportal VATS anatomical resections can be performed under different locoregional anesthesia techniques, but the most commonly used are epidural anesthesia, intercostal blocks or local anesthesia (25).

For the epidural anesthesia, a catheter is placed between T4–5 and after initial administration of bupivacaine 0.5% with adrenaline, then 4–5 cc bolus ropivacaine 0.375% are infused to achieve the blockade between T2 and T9 (Figure 4). In our experience, epidural anesthesia is a useful approach for locoregional analgesia, but a bilateral block with occasional episodes of urinary retention or constipation seems a more invasive technique when compared to selective unilateral intercostal block under direct view.

Figure 4.

Epidural catheter placement during thoracic surgery

Before the skin incision, local lidocaine 2% is applied to diminish the risk of triggering pain stimuli. There are some reports of nonintubated and awake procedures under local anesthesia, but none of them report experience with uniportal VATS.

We routinely perform intercostal blocks from 3rd to 7th intercostals posterior space (26), with bupivacaine 0.5%, 1–1.5 cc in each space at the beginning of the procedure, and at the end of the procedure, before closing the incision, we repeat again the block, and sometimes we extend it until the 2nd intercostal space for relieving the pain occasioned by the tip of the chest tube. There are many techniques for intercostal block. Initially we performed the block with an intramuscular needle from the back of the patient in order to keep the parietal pleura intact, but it can be troublesome in obese patients. Then we changed our technique and performed the block under direct thoracoscopic view with a fine gauge (Figure 5). Intercostal block is a more selective unilateral block, without systemic adverse events (urinary retention, constipation) and the duration of the analgesia reaches the first 24 h, when the chest tube is usually removed. We have now a randomized trial comparing pain control with epidural catheter and intercostals block, but preliminary results are not ready yet.

Figure 5.

Intercostal multiple block with local anesthesia with direct thoracoscopic view (27). Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1679

Other locoregional techniques have been described, such as paravertebral catheters or anterior serratus blockades (28) but they have been less described in nonintubated series.

Oxygenation

Although spontaneously breathing, these patients usually require some support for oxygenation due to the surgical pneumothorax and the “re-breathing” of exhaled air. There are several devices available including the laryngeal mask, but our anesthesiology team mainly prefers (Figure 6): oropharyngeal cannula, facial mask and high-flow oxygen nasal prongs. Oropharyngeal cannula with high FiO2 minimizes the risk of hypoxemia, and can be easily positioned with intranasal local anesthesia (Figure 7). Facial mask with Guedel cannula or high-flow oxygen nasal prongs have the same purpose, but in our opinion, they are less appropriate than oropharyngeal cannula whose tip lies immediately above the vocal cords and increases oxygen concentration in inspirated air.

Figure 6.

Oxygenation devices used during nonintubated procedures: from left to right on the top, nasal prongs, facial mask, high-flow oxygen nasal prongs. At the bottom, oropharyngeal cannula.

Figure 7.

Oropharyngeal cannula in the setting-up of a nonintubated uniportal VATS right-upper lobectomy.

Oxygenation can be ensured through these techniques, but main concerns focus on the risk of hypercapnia. Secondary to “re-breathing” and deep sedation needed for anatomical resections, moderate hypercapnia is usually observed. In case of severe hypercapnia, we reduce the propofol infusion and we assist the patient with the facial mask until recovering normal parameters, but if severe hypercapnia remains, conversion to tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation should be considered, especially in patients with some degree of pulmonary compromise.

Vagal block

Cough reflex is one of the first challenges when facing nonintubated procedures. It seems that dissecting vascular structures without cough control is not safe due to the risk of a major bleeding. During these years of experience, we have noticed that young patients are more reactive to lung or bronchial pulling than older patients. For minor procedures such as wedge resections, initial attempts without vagal block can be done in order to test patient reactivity.

For anatomical resections, it is mandatory to perform the vagal block with Bupivacaine 0.5%, 2–3 cc. We inject the local anesthetic in the lower paratracheal area or in the aortopulmonary window, for right and left resections respectively (Figure 8). Left vagal block is better performed pulling gently the lung anteriorly and incising the mediastinal pleura just after the laryngeal recurrent nerve visualization. Vagal block ensures cough abolition during 12 h so most anatomical resections can be safely performed. It is better to block the vagal transmission before initiating parenchyma or bronchial pulling maneuvers in order to avoid cough reflex triggering. Some other techniques have been described for cough control, such as intravenous or aerosolized local anesthetic (20), but they are less effective than direct vagal block.

Figure 8.

Vagal block with local anesthesia, performed in the right lower paratracheal area or in the left aortopulmonary window (29). Bupivacaine 0.5% is commonly used due to the duration of the effect. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1680

Surgical tips and tricks

The concept of performing anatomical resections in spontaneously breathing patients has the aim of achieving the same surgical conditions to perform safely the procedure, as with the standard intubated patients. Physiology of surgical pneumothorax endangers this purpose due mainly to the mediastinal movement. When initiating the procedure after pleural incision, patient feels discomfort because surgical pneumothorax has been developed, so an increase in the respiratory rate and the depth of breathing begins. Performing the intercostal and vagal block (for pain relief and cough abolition) and waiting 1–2 min allows the patient to get used to these changes and normalize the respiratory rate (preferably between 12–20 bpm) and what is most important, to normalize the depth of breathing so the mediastinal movement minimizes. Then, operating under these conditions is almost indistinguishable from intubated patients.

Normal operating time between 2–3 h usually allow keeping these conditions, but we’ve noticed that in more prolonged procedures mediastinal movement increases again, usually at the time of lymphadenectomy. Surgeon should select those procedures that can be surely performed in 2–3 h in order to reach safe conditions. If the operating time extends, vagal block can be repeated.

Dissection of bronchial and vascular structures should be gently performed, trying to minimize the risk of an injury or a bleeding because the management of a crisis under these conditions needs training and safety protocols. During some phases of the resection, surgical field could present to the surgeon as a “mobile” scenario when compared to intubated patients, so some kind of synchronization is advisable during the dissection and division of vascular structures. But as aforementioned, balancing the depth of sedation and performing intercostals and vagal block turns the surgical field indistinguishable from intubated patients. Figure 9 shows a nonintubated uniportal VATS right-upper lobectomy for lung cancer in 120 min. Anatomical segmentectomies can also be performed through this approach, as Figure 10 shows.

Figure 9.

Nonintubated uniportal VATS right-upper lobectomy plus lymphadenectomy in early stage lung adenocarcinoma (30). Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1681

Figure 10.

Nonintubated uniportal VATS left-lower lobe upper segmentectomy (S6) due to a colorectal carcinoma metastasis (31). Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1682

As a global concept, during non-intubated anatomical resections all the staff in the OR should be motivated with the procedure, and a relaxing environment is advisable. This relaxing atmosphere decreases emotional tension and helps should a complication happens. It is essential to keep in mind that although innovative and unusual in most centers, when the safety conditions are accomplished, these procedures are performed in a routine and comfortable way.

Crisis management

As previously mentioned, we consider mandatory that only experienced teams perform nonintubated uniportal VATS anatomical resections, defined by the following criteria: the surgeons, anesthesiologists and OR nurses must have performed more than 50 conventional VATS, must have overcome the learning curve in conventional multi-portal VATS and uniportal VATS (more than 50 major procedures through each approach) and have experience with difficult cases of major lung resections (big and central tumors, sleeve-resections, tumors of the apex, locally advanced tumors with diaphragm, chest wall, pericardium), and management of complications such as moderate to severe bleeding through uniportal approach. Anesthesiologists must be trained in the lateral intubation at least in 20 cases (left and right).

We set specific equipment in case we have to convert into an emergent thoracotomy or general anesthesia (called “emergency table”) and is composed by the elements included in Table 3 (Figure 11) (20).

Table 3. Elements that should be part of an Emergent Table should a complication happens, in order to ensure the safety of the patient, mainly focused on general anesthesia and orotracheal intubation.

| Element of the emergent table |

| Guedel cannula |

| Macintosh laryngoscope and two blade sizes |

| Double lumen Airtraq video laryngoscope |

| Two sizes of double-lumen tubes [35,37] |

| Two sizes of single-lumen orotracheal tubes (7 and 7.5 mm internal diameter) |

| Endobronchial blocker |

| Bronchofiberscope ready to use (3.7 mm) |

| Anesthesia induction agents (propofol, fentanyl, rocuronium) |

| Neuromuscular reversal agents (Sugammadex) |

| Thoracic chest tube (straight 24 Fr) |

Figure 11.

Emergency Table elements: the picture shows the required elements for management of a crisis during nonintubated uniportal VATS anatomical resections, as detailed in Table 3.

All the members of the team know what to do in every moment. We have had several briefing meetings before we start the procedure.

If a surgical emergency happens (severe bleeding) and the patient is stable the leader is the surgeon. If a medical emergency happens (oxygen desaturation or severe hypercapnia), the anesthesiologist takes control of the situation and can stop the procedure, which becomes essential to allocate the staff (nurses). We have three nurses in the operation room, so if an emergency happens, one nurse works with the surgeon and the others work with the anesthesiologist.

To train these skills we have a manikin (SimMan® Laerdal, Wappingers Falls, USA) where we simulate different crisis situations to train the staff.

The main crisis situations and their management are as follows:

Respiratory acidosis

The permissive hypercapnia is very common in nonintubated procedures, but if a severe hypercapnia develops, we always have a non-invasive ventilator prepared, propofol infusion is reduced and the patient assisted with facial mask until recovering normal parameters, but if remains, conversion to tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation should be considered.

Hypoxemia

During the surgery, our objective is to maintain oxygen saturation over 95%, which is normally reached with the administration of oxygen through the devices aforementioned. In case of a severe hypoxemia we first use a high flow oxygen ventilation (Optiflow®, Fisher and Paykel, Auckland, New Zealand) with the lower flow that increases the volume of the non-dependent lung, usually 20–30 L/min and 100% oxygen fraction. If the patient is still hypoxemic, we can use the non-invasive ventilation. In our experience, if the patient does not tolerate the high flow ventilation, then the need to intubate in the side position is the only solution. In this situation, as in severe hypercapnias with respiratory acidosis, we induce general anesthesia, intubate the patient in lateral decubitus, and introduce thoracic drainage through the incision. Once done, we connect it to water seal system and close the wound with a sterile transparent dressing around the drainage, to let the lung re-expand again and improve oxygen saturation or dyspnea.

Massive bleeding

In case of an emergent bleeding we would use one of the catheters to introduce a rapid infuse catheter set (RIC®, Teleflex, Wayne, USA) to infuse fluids rapidly. On a regular basis, we don’t cannulate central venous catheters, only after the patient is intubated and with the RIC inserted. If the complication is life threatening we need to temporarily control it while conversion by the anesthesiologist is initiated, and meanwhile converting the uniportal incision into an anterolateral thoracotomy, meanwhile compression through a sponge-stick through the incision is done first of all. After the thoracotomy is opened, we can remove the compressing sponge-stick and control the bleeding by standard techniques for hemostasis.

Conversion to multiport VATS

Several situations may challenge the surgeon’s skill to solve it through uniportal VATS but do not need emergent maneuvers:

Extensive adhesions of the lung to the chest wall;

Big tumors, particularly in the most central and anterior lung that make difficult to manipulate the hilar structures through the single incision;

Non-adequate lung collapse which difficult lung mobilization;

Mild bleeding (small pulmonary artery and vein branches, bronchial arteries).

With thoracoscopic view through the incision, one or two more thoracoscopic ports are designed.

Conclusions

Nonintubated uniportal VATS anatomical resections have been reported to be safe and feasible, but there are still many concerns regarding the selection criteria of the patients, and the potential advantages, due to the lack of evidence based on randomize comparative trials. Performed only in highly experienced centers in nonintubated surgery and uniportal VATS, main efforts have focused more in new technical challenges and indications than in acquiring solid scientific evidence. Anatomical resections such as lobectomies or segmentectomies under intercostal and vagal blocks, with oxygenation devices such as oropharyngeal canulla can be safely performed (9,12,14,26), but some potential complications should be kept in mind and emergency protocols for the management of crisis are mandatory (20). Patients are best managed under deep sedation avoiding the stressful perception induced by surgical pneumothorax, but one of the main challenges is to achieve a surgical stable field without respiratory depression and severe hypercapnia. Strictly selected patients under these considerations can be safely managed as standard intubated procedures with potential benefits in terms of postoperative recovery and immune antitumoral response profile.

Acknowledgements

To all the professionals that have worked hard in the setting of the nonintubated program in our center since 2013, who dedicate their efforts and motivation to the patients. To my wife, my family and friends for believing in the kind nature of this project.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Mineo TC, Tacconi F. Nonintubated thoracic surgery: a lead role or just a walk on part? Chin J Cancer Res 2014;26:507-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shao W, Phan K, Guo X, et al. Non-intubated complete thoracoscopic bronchial sleeve resection for central lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:1485-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng G, Cui F, Ang KL, et al. Non-intubated combined with video-assisted thoracoscopic in carinal reconstruction. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:586-93. 10.21037/jtd.2016.01.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Rivas D, Yang Y, Sekhniaidze D, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic bronchoplastic and carinal sleeve procedures. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S210-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez-Rivas D, Delgado M, Fieira E, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic pneumonectomy. J Thorac Dis 2013;5 Suppl 3:S246-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez-Rivas D, Delgado M, Fieira E, et al. Double sleeve uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2014;3:E2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galvez C, Bolufer S, Navarro-Martinez J, et al. Non-intubated video-assisted thoracic surgery management of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Transl Med 2015;3:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pompeo E. Pathophysiology of surgical pneumothorax in the awake patient. In: Pompeo E. editor. Awake thoracic surgery (Ebook). Sharja: U.A.E., Bentham Science Publishers, 2012:9-18. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo Z, Yin W, Pan H, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery segmentectomy by non-intubated or intubated anesthesia: a comparative analysis of short-term outcome. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:359-68. 10.21037/jtd.2016.02.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Rivas D, Fernandez R, de la Torre M, et al. Single-port thoracoscopic lobectomy in a nonintubated patient: the least invasive procedure for major lung resection? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;19:552-5. 10.1093/icvts/ivu209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung MH, Cheng YJ, Hsu HH, et al. Nonintubated uniportal thoracoscopic segmentectomy for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:e234-5. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Rivas D, Yang Y, Guido Wet al. Non-intubated (tubeless) uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2016;5:151-3. 10.21037/acs.2016.03.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hung MH, Cheng YJ, Chan KC, et al. Nonintubated uniportal thoracoscopic surgery for peripheral lung nodules. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:1998-2003. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hung WT, Hsu HH, Hung MH, et al. Nonintubated uniportal thoracoscopic surgery for resection of lung lesions. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S242-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung MH, Liu YJ, Hsu HH, et al. Nonintubated video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for management of indeterminate pulmonary nodules. Ann Transl Med 2015;3:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Rivas D. Uniportal thoracoscopic surgery: from medical thoracoscopy to non-intubated uniportal video-assisted major pulmonary resections. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2016;5:85-91. 10.21037/acs.2016.03.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Rivas D, Aymerich H, Bonome C, et al. From Open Operations to Nonintubated Uniportal Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Lobectomy: Minimizing the Trauma to the Patient. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:2003-5. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocco G. Non-intubated uniportal lung surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49 Suppl 1:i3-5. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rocco G, Romano V, Accardo R, et al. Awake single-access (uniportal) video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for peripheral pulmonary nodules in a complete ambulatory setting. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89:1625-7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.01.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navarro-Martínez J, Gálvez C, Rivera-Cogollos MJ, et al. Intraoperative crisis resource management during a non-intubated video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Ann Transl Med 2015;3:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen KC, Cheng YJ, Hung MH, et al. Nonintubated thoracoscopic lung resection: a 3-year experience with 285 cases in a single institution. J Thorac Dis 2012;4:347-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung MH, Hsu HH, Chan KC, et al. Non-intubated thoracoscopic surgery using internal intercostal nerve block, vagal block and targeted sedation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;46:620-5. 10.1093/ejcts/ezu054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Cui F, Li S, et al. Nonintubated video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under epidural anesthesia compared with conventional anesthetic option: a randomized control study. Surg Innov 2015;22:123-30. 10.1177/1553350614531662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galvez C, Bolufer S, Navarro-Martinez J, et al. Awake uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic metastasectomy after a nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:e24-6. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiss G, Castillo M. Nonintubated anesthesia in thoracic surgery: general issues. Ann Transl Med 2015;3:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galvez C, Navarro-martinez J, Bolufer S, et al. Non-intubated uniportal left-lower lobe upper segmentectomy (S6). J Vis Surg 2017;3:48 10.21037/jovs.2017.03.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galvez C, Navarro-Martinez J, Bolufer S, et al. Intercostal multiple block with local anesthesia with direct thoracoscopic view. Asvide 2017;4:365. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1679

- 28.Font MC, Navarro-Martinez J, Nadal SB, et al. Continuous Analgesia Using a Multi-Holed Catheter in Serratus Plane for Thoracic Surgery. Pain Physician 2016;19:E684-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galvez C, Navarro-Martinez J, Bolufer S, et al. Vagal block with local anesthesia, performed in the right lower paratracheal area or in the left aortopulmonary window. Asvide 2017;4:366. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1680

- 30.Galvez C, Navarro-Martinez J, Bolufer S, et al. Nonintubated uniportal VATS right-upper lobectomy plus lymphadenectomy in early stage lung adenocarcinoma. Asvide 2017;4:367. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1681

- 31.Galvez C, Navarro-Martinez J, Bolufer S, et al. Nonintubated uniportal VATS left-lower lobe upper segmentectomy (S6) due to a colorectal carcinoma metastasis. Asvide 2017;4:368. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1682