Abstract

Objective

Although cognitive stimulation (CS) is one of the most popular non-pharmacological interventions for people with dementia, its efficacy is still debatable. We performed a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the efficacy of CS in people with dementia.

Methods

Data sources were identified by searching PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, psychINFO, and Cochrane Reviews Library. A total of 7,354 articles were identified, and of these, 30 RCTs were selected based on the selection criteria. Of these 30 RCTs, 14 were finally included in our meta-analysis [731 participants with dementia; 412 received CS (CS group) and 319 received usual care (control group)].

Results

We found that the people with dementia had a moderate benefit from CS. The mean difference between the CS and control groups was 2.21 [95% CI (0.93, 3.49), Z=3.38, p=0.00007] in the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognition and 1.41 [95% CI (0.98, 1.84), Z=6.39, p<0.00001] in the Mini-Mental State Examination. CS also improved quality of life in people with dementia [95% CI (0.72, 3.38), Z=3.02, p=0.003].

Conclusion

CS is effective for improving cognition and quality of life in people with dementia; however, its effects were small to moderate.

Keywords: Cognitive stimulation, Dementia, Meta-analysis, Cognition, Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Dementia has become one of the most challenging global health problems. The number of people with dementia has been estimated to be 35.6 million, and the number has been predicted to double every 20 years and reach 115.4 million by 2050.1 In Korea, one of the most rapidly aging countries in the world, the number of people with dementia is expected to double every 17 years.2 People with dementia show gradual but progressive loss of cognition, and more than half of the people with dementia experience behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD).3 These people need supervision or support for their instrumental and basic activities of daily living (ADL). Caregivers of people with dementia experience physical, emotional, and financial burdens. The efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia has been reported to be limited,4,5,6 and there is currently no cure for dementia. The importance of non-pharmacological interventions for people with dementia has increased.

Non-pharmacological interventions in combination with pharmacotherapies have been widely used in the management of people with dementia.7,8 Neural plasticity and capacity for cognitive-deficit compensation may underlie the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions.9 Cognitive stimulation (CS) is one of the most popular non-pharmacological interventions for people with dementia.10 It is usually provided in a group and more flexible than cognitive training as it does not have to match specific therapeutic modalities. Several previous studies reported that CS may delay functional impairments11,12 and improve quality of life (QoL)13,14,15 in people with dementia. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) recommends the application of CS to people with dementia in the UK.16 However, the therapeutic efficacy of CS in people with dementia has been in controversy because of the diversity of outcome measures and definition of CS employed in previous clinical trials. Several studies on CS were not clear with regard to the concepts of “training,” “stimulation,” and “rehabilitation.”

We performed a meta-analysis to investigate the effectiveness of CS on cognition, BPSD, mood, ADL, and QoL in people with dementia. In this meta-analysis, we defined CS as “an engagement in a range of activities and discussions aimed at general enhancement of cognitive and social functioning” proposed by Clare et al.11,17,18

METHODS

We followed the meta-analysis guidelines corroborated by the National Evidence-based Health Care Collaborating Agency (NECA), Korea.19

Inclusion criteria of the studies

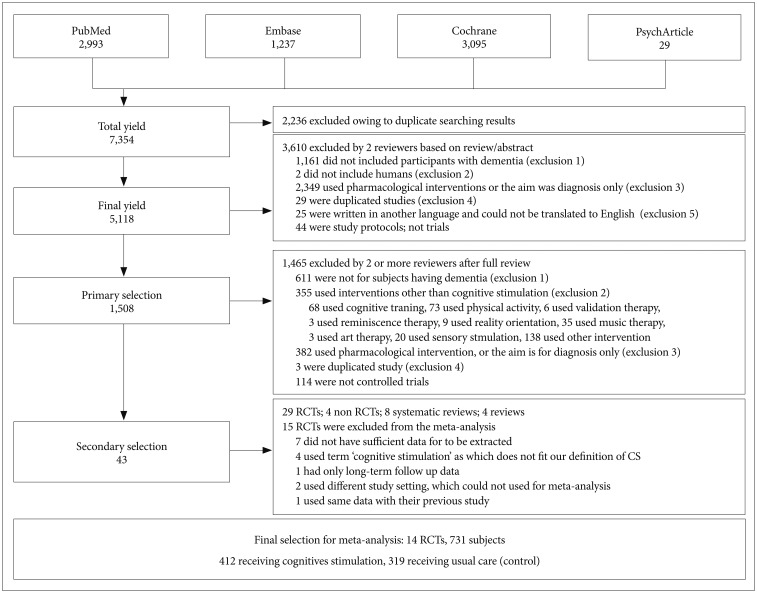

The study flow chart is presented in Figure 1. This meta-analysis focused on RCTs that provided relevant statistical information. Only studies published in English were considered for inclusion. The following criteria were considered: 1) participants had a diagnosis of dementia; 2) all levels of dementia severity that were indicated through group mean scores, range of scores, or individual scores using standardized scales, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)20 and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR),21 were included; 3) data from family members or caregivers were not included; 4) age of the participants and type of dementia were not limited; and 5) the number of participants taking cognitive enhancers was mentioned if necessary.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study selection procedure in this meta-analysis.

We considered CS as “an engagement in various activities and discussions (usually in a group) aimed at general enhancement of cognitive and social functioning,” according to the definition proposed by Clare et al.11 We regarded “no treatment,” “usual care,” and “standard treatment” as controls. The term ‘no treatment’ was cognitive enhancer, clinic consultations, or contact with mental health team without any structured intervention that could be normally provided in usual treatment settings. There were no restrictions on the duration of interventions or the number of sessions. However, these values were noted.

The following variables were considered as outcome measures for the analyses: 1) the MMSE, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognition (ADAS-Cog),22 Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA),23 or other cognition assessment measures for cognitive impairment associated with global cognitive function; 2) self-reported function, clinically rated function, or caregiver-reported function measures for mood; 3) caregiver-reported function or clinically-rated function measures for behavioral and psychological symptoms; 4) self-reported function or caregiver-reported function measures for QoL, such as the QoL scale in Alzheimer's disease (QoL-AD)24; and 5) self-reported function or caregiver-reported function measures for ADL.

Search methods for the identification of studies

We searched the electronic medical databases PubMed, MEDLINE (1966 to April 2015), Embase (1980 to April 2015), psychINFO (1887 to April 2015), and Cochrane Reviews Library (1982 to April 2015) for all relevant English articles. Because of the ambiguity regarding interventions, we selected multiple keywords to improve sensitivity. First, medical subject heading (MeSH) terms were used for literature search, including CS, cognitive rehabilitation, cognitive training, cognitive rehabilitation program, cognitive therapy, nonpharmacological, memory training, exercise, physical activity, music therapy, art therapy, horticulture therapy, occupational therapy, validation therapy, reality orientation, and reminiscence. We then used the Boolean operation (OR) for sensitive search. The search strategies were as follows:

#1 Search (dementia) OR mild cognitive impairment

#2 Search ((((((((((((((((cognitive rehabilitation) OR (cognitive stimulation) OR cognitive training) OR cognitive rehabilitation program) OR cognitive therapy) OR nonpharmacological) OR memory training) OR exercise) OR physical activity) OR music therapy) OR art therapy) OR horticulture therapy) OR occupational therapy) OR validation therapy) OR reality orientation) OR reminiscence))))))))))))))))

#3 Search #1 and #2 filters: Clinical trial; Controlled clinical trial; Randomized controlled trial; Systematic reviews; Humans

To identify additional studies, reviews were hand-searched for both published and unpublished trials, and the authors were contacted if required.

Data collection and analysis

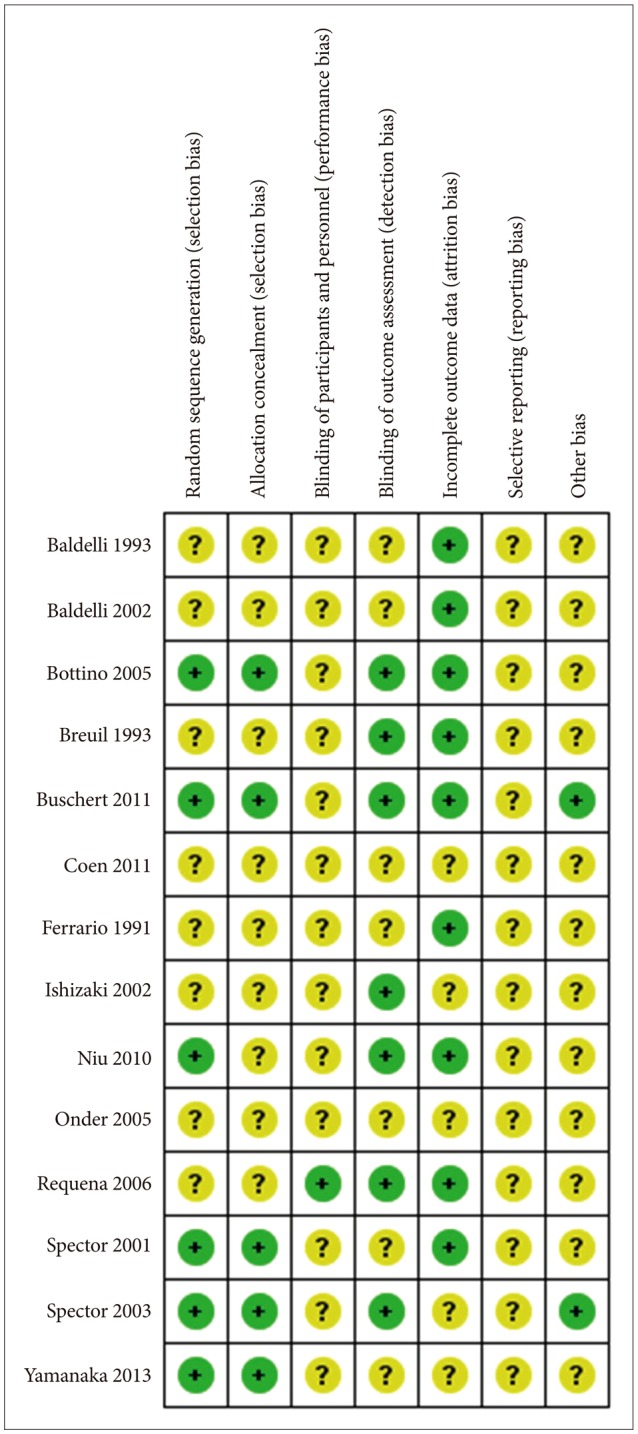

Primary selection was performed by reviewers independently based on the abstract. Then, secondary selection was performed by all researchers after full review. Regular consensus meetings were held to select studies according to the inclusion criteria. Studies were excluded if 1) the subjects were cognitively normal or had other neurological disorders that did not meet the criteria of dementia (DSM-IV-TR)25; 2) subjects were not human; 3) interventions were non-pharmacological methods that did not involve CS or were pharmacological methods; 4) the study was a duplicate publication; and 5) we could not find the original abstract or article, or we could not translate the study to English. The reviewers used a standardized abstracted form adapted from the Korean National Evidence-based Health Care Collaborating Agency (NECA) 19. All included studies were reviewed and graded according to the risk of bias checklist, using the Cochrane approach (risk of bias table) (Figure 2).

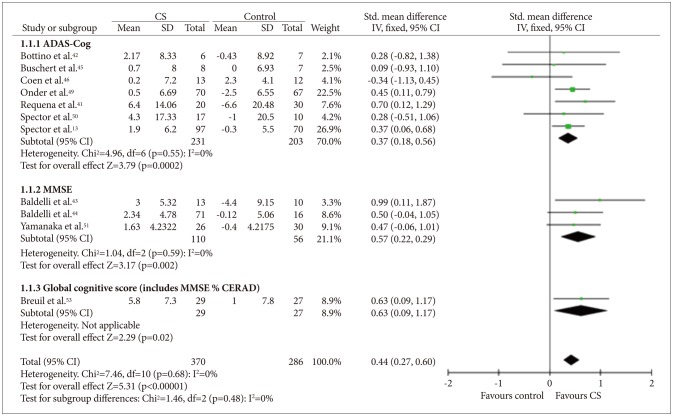

Figure 2. Cognitive stimulation versus no cognitive stimulation. Outcome: global cognition (overall). SD: standard deviation, Std. mean difference: standardized mean difference, IV, fixed: a fixed-effects meta-analysis with inverse variances weights, CI: confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom, tau2 and I2: heterogeneity values, Chi2: Chi-square test value, Z: Z-value as the overall effect, p: p-value.

The meta-analysis was performed using the software RevMan (Review Manager) Version 5.2. (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012). In most cases, summary effects were computed using a fixed-effects model, because the studies had similar settings and methodologies, and this approach provides more conservative result than a random-effects model. However, the random-effects model was used when statistical heterogeneity was proven by a Higgins' I-squared value of over 50% between studies.19,26 We did not consider the long-term effects of interventions. Effect sizes were analyzed as standardized mean differences (SMDs), and Cohen's d was used with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for comparisons between the active treatment (CS) and control (usual care) groups.

RESULTS

We identified a total of 7,354 articles in the literature search, and after deleting duplicate publications, 5,118 articles remained. After performing the processes of elimination, we identified 29 RCTs involving CS that met our inclusion criteria. Among these studies, 15 studies were excluded; seven studies did not have sufficient data for extraction,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 four studies employed different definition of CS,34,35,36,37 one study provided long-term follow-up data only,38 two studies compared the efficacy between two different types of CS,39,40 and one study14 shared the same dataset with their previous study.13 For Requena 2006,41 the ‘no treatment’ group was excluded owing to non-randomization; therefore, comparisons were only performed for CS+ drug. Finally, 14 studies were included in this meta-analysis.13,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53 From these studies, we identified 731 participants [412 received CS and 319 used usual care (control)]. Further information on the included and excluded studies is presented in Table 1 and 2.

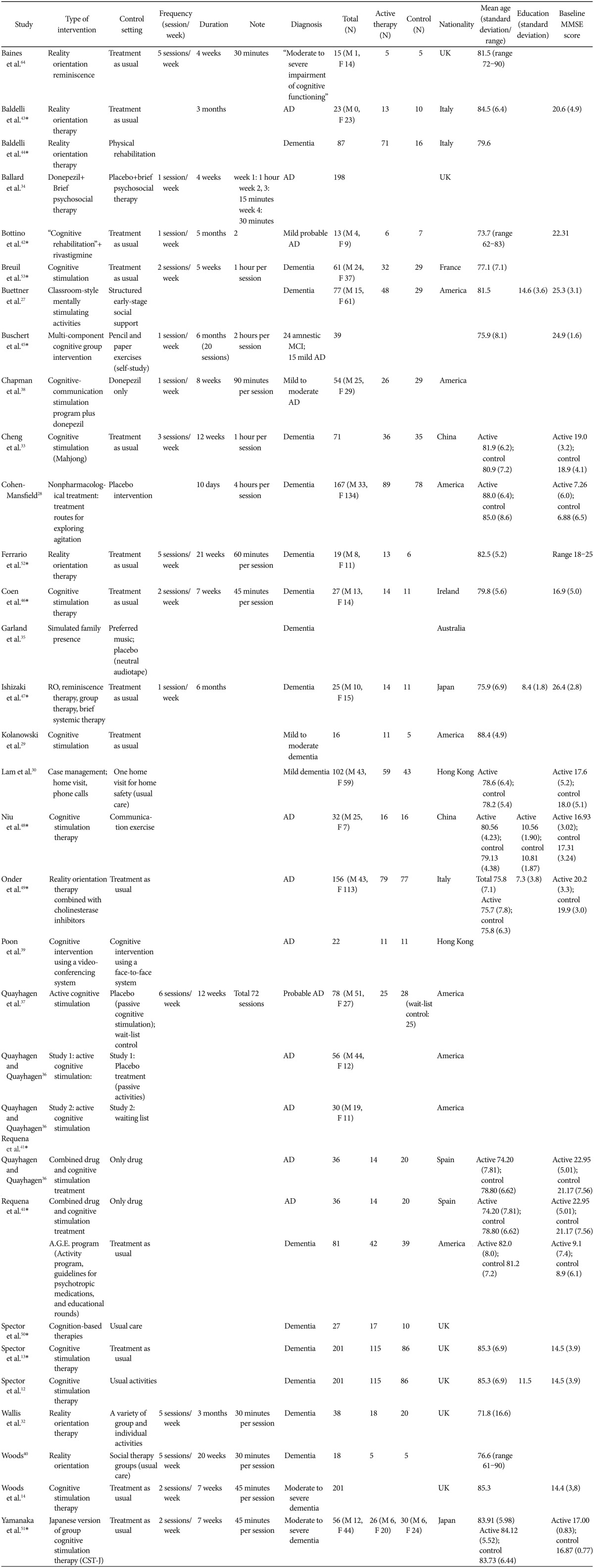

Table 1. Main characteristics of the included studies.

Each asterisks represents included studies. For Requena 2006, the no treatment group was excluded owing to non-randomization; therefore, comparisons were only performed for CS+drug

Table 2. Excluded studies.

Efficacy for cognition

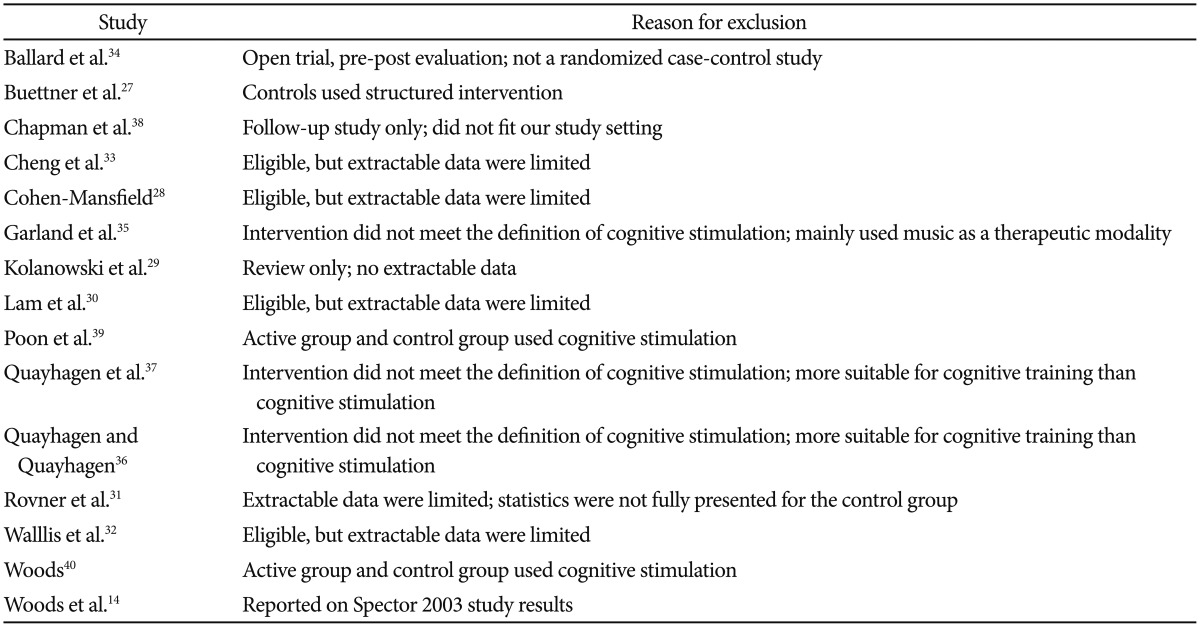

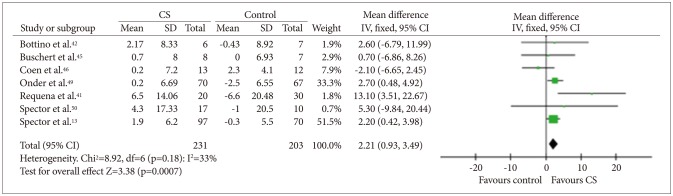

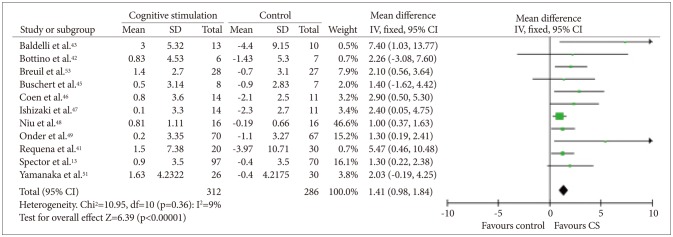

Data on cognition were available in 12 studies,12,13,41,42,43,44,45,46,49,50,51,53 which included 370 participants who received CS and 286 who received usual care. The SMD between the CS and control groups was 0.44 [95% CI (0.27, 0.60)], and this value was statistically significant (fixed effect, Z=5.31, p<0.00001, I-square=0%) (Figure 2). As most of the studies used more than one outcome measure, analysis was performed on the most comprehensive measure. In seven studies that used the ADAS-Cog (Figure 3), the mean difference between the CS and control groups was 2.21 [95% CI (0.93, 3.49)], and this value was statistically significant (fixed effect, Z=3.38, p=0.00007, I-square=33%). In 11 studies that used the MMSE (Figure 4), the mean difference between the CS and control groups was 1.41 [95% CI (0.98, 1.84)], and this value was statistically significant (fixed effect, Z=6.39, p<0.00001, I-square=9%). However, we could not confirm the effectiveness of CS for specific cognitive domains as only one study reported on such effectiveness of CS.12 In that study, the improvement in language subscale (commands and spoken language items) was significantly better in the CS group than in the control group.

Figure 3. Cognitive stimulation versus no cognitive stimulation. Outcome: Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog). SD: standard deviation, IV, fixed: a fixed-effects meta-analysis with inverse variances weights, CI: confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom, tau2 and I2: heterogeneity values, Chi2: Chi-square test value, Z: Z-value as the overall effect, p: p-value.

Figure 4. Cognitive stimulation versus no cognitive stimulation. Outcome: MMSE. SD: standard deviation, IV, fixed: a fixed-effects meta-analysis with inverse variances weights, CI: confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom, tau2 and I2: heterogeneity values, Chi2: Chi-square test value, Z: Z-value as the overall effect, p: p-value.

Behavior and psychological symptoms (BPSD)

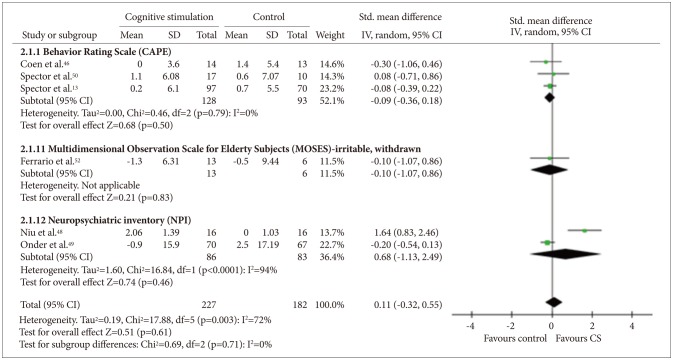

Six studies13,46,48,49,50,52 that included a total of 409 participants provided data on BPSD. Among these studies, three studies13,46,50 used the Clifton Assessment Procedures for the Elderly (CAPE),54 two48,49 used Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI),55 and one52 used the irritability and withdrawal subscales of the Multidimensional Observation Scale for Elderly Subjects (MOSES)56 (Figure 5). Quantitative analysis did not show any benefit of CS for the BPSD measures [random effect, SMD=0.32, 95% CI (-0.06, 0.70), Z=1.67, p=0.10].

Figure 5. Cognitive stimulation versus no cognitive stimulation. Outcome: behavioral and psychological symptoms. SD: standard deviation, Std. mean difference: standardized mean difference, IV, random: a ramdom-effects meta-analysis with inverse variances weights, CI: confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom, tau2 and I2: heterogeneity values, Chi2: Chi-square test value, Z: Z-value as the overall effect, p: p-value.

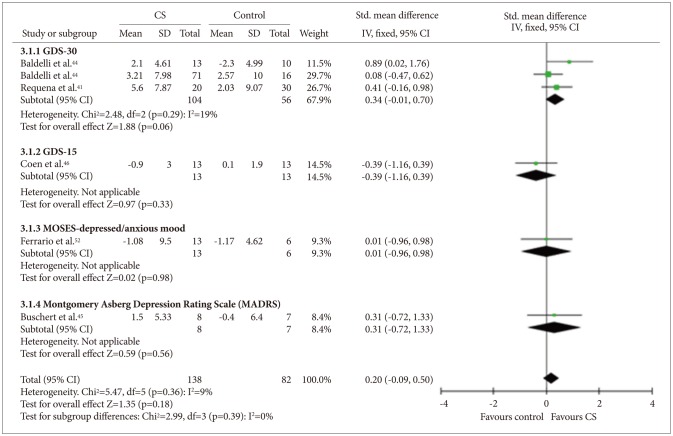

Mood

Six studies41,43,44,45,46,52 that included a total of 220 participants provided data on mood, and all described depression as a mood symptom. Among these studies, three studies41,43,44 used the 30-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-30),57 one 46 used the 15-item GDS (GDS-15),58 one 45 used the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and one52 used the depressed/anxious mood subscales of the MOSES (Figure 6). Quantitative analysis did not show any benefit of CS for the mood measures [fixed effect, SMD=0.20, 95% CI (-0.09, 0.50), Z=1.35, p=0.39].

Figure 6. Cognitive stimulation versus no cognitive stimulation. Outcome: mood. SD: standard deviation, Std. mean difference: standardized mean difference, IV, fixed: a fixed-effects meta-analysis with inverse variances weights, CI: confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom, tau2 and I2: heterogeneity values, Chi2: Chi-square test value, Z: Z-value as the overall effect, p: p-value.

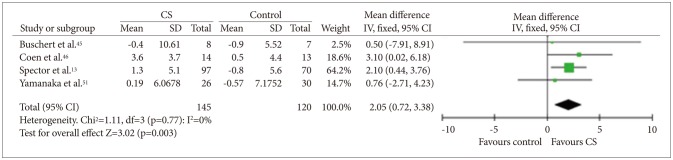

Quality of life (QoL)

Four studies45,46,50,51 that included a total of 265 participants provided data on QoL. All these studies used the QoL-AD (Figure 7). Quantitative analysis showed that CS was beneficial for QoL in people with dementia [fixed effect, SMD=2.05, 95% CI (0.72, 3.38), Z=3.02, p=0.003].

Figure 7. Cognitive stimulation versus no cognitive stimulation. Outcome: Quality of life. SD: standard deviation, IV, fixed: a fixed-effects meta-analysis with inverse variances weights, CI: confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom, tau2 and I2: heterogeneity values, Chi2: Chi-square test value, Z: Z-value as the overall effect, p: p-value.

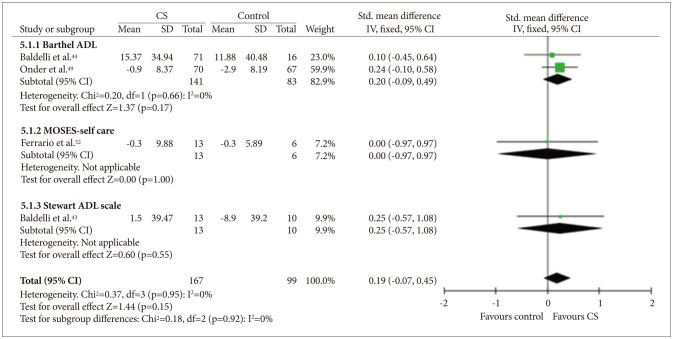

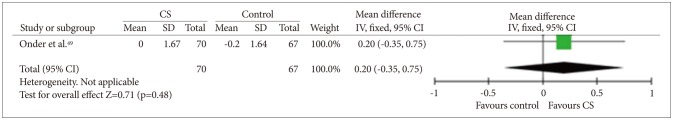

ADL and instrumental ADL

Three studies43,44,52 measured only basic ADL, and one study49 measured both basic and instrumental ADL (Figures 8 and 9). Quantitative analysis did not show any benefit of CS for basic ADL measures [fixed effect, SMD=0.19, 95% CI (-0.07, 0.45), Z=1.44, p=0.92]. Quantitative analysis for instrumental ADL was not possible because only one study assessed instrumental ADL and there was no significant difference in improvement between the study groups.

Figure 8. Cognitive stimulation versus no cognitive stimulation. Outcome: ADL. SD: standard deviation, Std. mean difference: standardized mean difference, IV, fixed: a fixed-effects meta-analysis with inverse variances weights, CI: confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom, tau2 and I2: heterogeneity values, Chi2: Chi-square test value, Z: Z-value as the overall effect, p: p-value.

Figure 9. Cognitive stimulation versus no cognitive stimulation. Outcome: Instrumental ADL. SD: standard deviation, IV, fixed: a fixed-effects meta-analysis with inverse variances weights, CI: confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom, tau2 and I2: heterogeneity values, Chi2: Chi-square test value, Z: Z-value as the overall effect, p: p-value.

DISCUSSION

In this meta-analysis, CS was found to be effective for improving global cognition (1.80 points in the ADAS-Cog and 2.60 in the MMSE). The MMSE score has been reported to decline by 2–4 points annually in mild and moderate dementia patients.17 Although the improvement in global cognition with CS was not associated with a significant improvement in ADL, the findings portrayed an optimistic view of CS as a standard non-pharmacological therapy for dementia. Although it is yet not fully understood how CS preserves cognitive function in people with dementia, maintaining mental activities may protect against cognitive decline59,60 by facilitating brain plasticity, proliferation and survival of hippocampal neurons,61 and the enlargement of the brain and/or cognitive reserve.62 In the present study, we could not perform a meta-analysis on the effectiveness of CS for each specific cognitive domain owing to the insufficient number of studies. However, in some previous studies,47,50 CS was effective in improving commands and spoken language.

Maximizing QoL in people with dementia is one of the major goals in the management of dementia. As QoL in people with dementia is important to family caregivers and health service providers, as well as the people with dementia themselves, QoL is often included as an outcome measure in clinical trials on dementia.63 In the present study, although the effect size was small to moderate, we found that CS significantly improved the QoL-AD scores in people with dementia. Interventions that can enhance cognition have been reported to improve the sense of well-being and the QoL in people with dementia.30

In this study, CS was not beneficial for improving mood and BPSD, as in a previous Cochrane review.17 However, these results do not necessarily indicate that CS may not be helpful at all for improving mood and/or BPSD. The lack of efficacy of CS for mood, and BPSD in the present study may be attributed, at least in part, to the fact that people with dementia having severe mood symptoms or BPSD were excluded from most clinical trials on the efficacy of CS.53 In addition, some open-label studies have shown the efficacy of CS for mood and/or BPSD in people with dementia. For example, Ballard et al.34 reported that CS improved the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory score in people with dementia.

Current study has several limitations. First, most studies included in this meta-analysis had unclear risk of bias (Figure 10). We failed to find truly double-blinded studies in this analysis. The participants and staffs might have been aware of their treatment condition, which could lead to biased results. Second, there was broad heterogeneity in the study settings and the actual elements of the CS program. Third, the “sham” type of activities that were employed as control or placebo therapy had some components of CS according to the definition of Clare et al.11 Actually, unorthodox group activities have also been reported to be effective in people with dementia.17,40,41 Fourth, the studies included in the present meta-analysis did not provide the efficacy of CS according to the type of dementia. The efficacy of CS may not be uniform across different types of dementia. Furthermore, the efficacy of CS has never been studied in rare types of dementia. Fifth, the analyses were insufficient to prove the quantitative therapeutic correlation of CS. Some studies in this analysis did not clearly present the duration and frequency of the intervention. Further research is warranted on the relationship between the intervention and the dose effect.

Figure 10. Risk of bias summary: Review of authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

In conclusion, CS is more effective than usual activities for improving global cognition and QoL in people with dementia.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare, and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea [grant number HI09C1379 (A092077)] and from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number HI12C2018).

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Dementia: A Public Health Priority. World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KW, Park JH, Kim MH, Kim MD, Kim BJ, Kim SK, et al. A nationwide survey on the prevalence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in South Korea. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23:281–291. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Steffens DC, Breitner JC. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:708–714. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell N, Ayub A, Boustani MA, Fox C, Farlow M, Maidment I, et al. Impact of cholinesterase inhibitors on behavioral and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:719–728. doi: 10.2147/cia.s4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballard C, Margallo-Lana M, Juszczak E, Douglas S, Swann A, Thomas A, et al. Quetiapine and rivastigmine and cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330:874. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38369.459988.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 2005;293:596–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson RS, Mendes De Leon CF, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, Evans DA, et al. Participation in cognitively stimulating activities and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287:742–748. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International AsD. World Alzheimer Report 2011: The Benefits of Early Diagnosis and Intervention. London: Alzheimer's Disease International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern Y, Moeller JR, Anderson KE, Luber B, Zubin NR, DiMauro AA, et al. Different brain networks mediate task performance in normal aging and AD: defining compensation. Neurology. 2000;55:1291–1297. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.9.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Dementia: A NICE-SCIE Guideline on Supporting People with Dementia and Their Carers in Health and Social Care. London: British Psychological Society; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clare L, Woods RT, Moniz Cook ED, Orrell M, Spector A. Cognitive rehabilitation and cognitive training for early-stage Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD003260. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spector A, Orrell M, Woods B. Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST): effects on different areas of cognitive function for people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:1253–1258. doi: 10.1002/gps.2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Woods B, Royan L, Davies S, Butterworth M, et al. Efficacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia: Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:248–254. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woods B, Thorgrimsen L, Spector A, Royan L, Orrell M. Improved quality of life and cognitive stimulation therapy in dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10:219–226. doi: 10.1080/13607860500431652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orrell M, Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Woods B. A pilot study examining the effectiveness of maintenance Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (MCST) for people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:446–451. doi: 10.1002/gps.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scottish Inercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) Management of Patients with Dementia, clinical guideline 86. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, Orrell M. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD005562. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005562.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clare L, Woods RT. Cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation for people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease: a review. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2004;14:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S, Park J, Seo H, Jang B, Son H, Shin C, et al. NECA's Guidance for Undertaking Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Intervention. Seoul: National Evidence-Based Healthcare Collaborating Agency; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356–1364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorgrimsen L, Selwood A, Spector A, Royan L, de Madariaga Lopez M, Woods R, et al. Whose quality of life is it anyway?: the validity and reliability of the Quality of Life-Alzheimer's Disease (QoL-AD) scale. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2003;17:201–208. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association AP. DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins J, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buettner LL, Fitzsimmons S, Atav S, Sink K. Cognitive stimulation for apathy in probable early-stage Alzheimer's. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:480890. doi: 10.4061/2011/480890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: a review, summary, and critique. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:361–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolanowski AM, Fick DM, Clare L, Steis M, Boustani M, Litaker M. Pilot study of a nonpharmacological intervention for delirium superimposed on dementia. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2011;4:161–167. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20101001-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam LC, Lee JS, Chung JC, Lau A, Woo J, Kwok TC. A randomized controlled trial to examine the effectiveness of case management model for community dwelling older persons with mild dementia in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:395–402. doi: 10.1002/gps.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rovner BW, Steele CD, Shmuely Y, Folstein MF. A randomized trial of dementia care in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb05631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallis GG, Baldwin M, Higginbotham P. Reality orientation therapy -- a controlled trial. Br J Med Psychol. 1983;56:271–277. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1983.tb01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng ST, Chow PK, Song YQ, Yu EC, Chan AC, Lee TM, et al. Mental and physical activities delay cognitive decline in older persons with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballard C, Brown R, Fossey J, Douglas S, Bradley P, Hancock J, et al. Brief psychosocial therapy for the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer disease (the CALM-AD trial) Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:726–733. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b0f8c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garland K, Beer E, Eppingstall B, O'Connor DW. A comparison of two treatments of agitated behavior in nursing home residents with dementia: simulated family presence and preferred music. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:514–521. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000249388.37080.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quayhagen MP, Quayhagen M. Testing of a cognitive stimulation intervention for dementia caregiving dyads. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2001;11:319–332. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quayhagen MP, Quayhagen M, Corbeil RR, Roth PA, Rodgers JA. A dyadic remediation program for care recipients with dementia. Nurs Res. 1995;44:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapman SB, Weiner MF, Rackley A, Hynan LS, Zientz J. Effects of cognitive-communication stimulation for Alzheimer's disease patients treated with donepezil. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2004;47:1149–1163. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/085). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poon P, Hui E, Dai D, Kwok T, Woo J. Cognitive intervention for communityXMLLink_XYZ dwelling older persons with memory problems: telemedicine versus face-to-face treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:285–286. doi: 10.1002/gps.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woods RT. Reality orientation and staff attention: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:502–507. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.5.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Requena C, Maestu F, Campo P, Fernandez A, Ortiz T. Effects of cholinergic drugs and cognitive training on dementia: 2-year follow-up. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disorder. 2006;22:339–345. doi: 10.1159/000095600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bottino CM, Carvalho IA, Alvarez AMM, Avila R, Zukauskas PR, Bustamante SE, et al. Cognitive rehabilitation combined with drug treatment in Alzheimer's disease patients: a pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19:861–869. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr911oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baldelli MV, Pirani A, Motta M, Abati E, Mariani E, Manzi V. Effects of reality orientation therapy on elderly patients in the community. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1993;17:211–218. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(93)90052-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baldelli M, Boiardi R, Fabbo A, Pradelli J, Neri M. The role of reality orientaion therapy in restorative care of elderly patients with dementia plus stroke in the subacute nursing home setting. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Suppl. 2002;8:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(02)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buschert VC, Friese U, Teipel SJ, Schneider P, Merensky W, Rujescu D, et al. Effects of a newly developed cognitive intervention in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer's disease: a pilot study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25:679–694. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-100999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coen RF, Flynn B, Rigney E, O'Connor E, Fitzgerald L, Murray C, et al. Efficacy of a cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia. Ir J Psychol Med. 2011;28:145–147. doi: 10.1017/S0790966700012131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishizaki J, Meguro K, Ohe K, Kimura E, Tsuchiya E, Ishii H, et al. Therapeutic psychosocial intervention for elderly subjects with very mild Alzheimer disease in a community: the tajiri project. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16:261–269. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niu YX, Tan JP, Guan JQ, Zhang ZQ, Wang LN. Cognitive stimulation therapy in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24:1102–1111. doi: 10.1177/0269215510376004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onder G, Zanetti O, Giacobini E, Frisoni GB, Bartorelli L, Carbone G, et al. Reality orientation therapy combined with cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:450–455. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spector A, Orrell M, Davies S, Woods B. Can reality orientation be rehabilitated? Development and piloting of an evidence-based programme of cognition-based therapies for people with dementia. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2001;11:377–397. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamanaka K, Kawano Y, Noguchi D, Nakaaki S, Watanabe N, Amano T, et al. Effects of cognitive stimulation therapy Japanese version (CST-J) for people with dementia: a single-blind, controlled clinical trial. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17:579–586. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.777395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferrario E, Cappa G, Molaschi M, Rocco M. Reality orientation therapy in institutionalized elderly patients: preliminary results. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1991;12:139–142. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Breuil V, De Rotrou J, Forette F, Tortrat D, Ganansia-Ganem A, Frambourt A, et al. Cognitive stimulation of patients with dementia: preliminary results. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1994;9:211–217. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pattie A, Gilleard C. Clifton Assessment Procedures for the Elderly. Windsor: NFER-Nelson; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Helmes E, Csapo KG, Short JA. Standardization and validation of the multidimensional observation scale for elderly subjects (MOSES) J Gerontol. 1987;42:395–405. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yesavage JA, Brink T, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Pychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Craen AJ, Heeren T, Gussekloo J. Accuracy of the 15XMLLink_XYZitem geriatric depression scale (GDSXMLLink_XYZ15) in a community sample of the oldest old. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:63–66. doi: 10.1002/gps.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:343–353. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00767-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fratiglioni L, Wang HX. Brain reserve hypothesis in dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;12:11–22. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Churchill JD, Galvez R, Colcombe S, Swain RA, Kramer AF, Greenough WT. Exercise, experience and the aging brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:941–955. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scarmeas N, Stern Y. Cognitive reserve and lifestyle. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25:625–633. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.625.14576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L. Quality of life in Alzheimer's disease: patient and caregiver reports. J Ment Health Aging. 1999;5:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baines S, Saxby P, Ehlert K. Reality orientation and reminiscence therapy. A controlled cross-over study of elderly confused people. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:222–231. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]