Abstract

Activation of quiescent hepatic stellate cells (q-HSCs) and their transformation to myofibroblasts (MFBs) is a key event in liver fibrosis. Hedgehog (Hh) signaling stimulates q-HSCs to differentiate into MFBs, and NADPH oxidase (NOX) may be involved in regulating Hh signaling. The author's preliminary study demonstrated that ursolic acid (UA) selectively induces apoptosis in activated HSCs and inhibits their proliferation in vitro via negative regulation of NOX activity and expression. However, the effect of UA on q-HSCs remains to be elucidated. The present study aimed to investigate the effect of UA on q-HSC activation and HSC transformation and to observe alterations in the NOX and Hh signaling pathways during q-HSC activation. q-HSC were isolated from adult male Sprague-Dawley rats. Following culture for 3 days, the cells were treated with or without transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1; 5 µg/l); intervention groups were pretreated with UA (40 µM) or diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI; 10 µM) for 30 min prior to addition of TGF-β1. mRNA and protein expression of NOX and Hh signaling components and markers of q-HSC activation were examined by western blotting and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. TGF-β1 induced activation of q-HSCs, with increased expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and type I collagen. In addition, expression of NOX subunits (gp91phox, p67phox, p22phox, and Rac1) and Hh signaling components, including sonic Hh, sterol-4-alpha-methyl oxidase, and Gli family zinc finger 2, were upregulated in activated HSCs. Pretreatment of q-HSCs with UA or DPI prior to TGF-β1 significantly downregulated expression of NOX subunits and Hh signaling components and additionally inhibited expression of α-SMA and type I collagen, thereby preventing transformation to MFBs. UA inhibited TGF-β1-induced activation of q-HSCs and their transformation by inhibiting expression of NOX subunits and the downstream Hh pathway.

Keywords: primary HSC, UA, NADPH oxidase, hedgehog signaling pathway

Introduction

Liver fibrosis is characterized by the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix, mainly type I collagen (1). Activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are the major source of extracellular matrix, and activation of quiescent HSCs (q-HSCs) and their transformation into myofibroblasts (MFBs) are considered key steps in the onset of hepatic fibrosis (2–4).

NADPH oxidase (NOX) mediates transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-induced HSC activation and transformation to MFBs (5), and the Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway also plays an important role in quiescent HSC activation and transformation to MFBs (6). Studies have shown that inhibition of Rac1 (a NOX subunit) expression can reverse the pro-fibrotic effect of Hh signaling (7), suggesting that NOX might stimulate Hh signaling.

Ursolic acid (UA) is a pentacyclic triterpenoid, and our preliminary study showed that UA selectively induces apoptosis in activated HSCs and inhibits their proliferation in vitro (8). Wang et al (9) also found that UA causes apoptosis in culture-activated HSCs but not in isolated hepatocytes and q-HSCs. Subsequently, we found that UA inhibits leptin-mediated expression of NOX subunits in an activated rat HSC cell line (HSC-T6), thereby suppressing activation of downstream ERK, PI3K/Akt, and p38 MAPK signaling pathways (10). However, it remains unknown whether UA exerts an inhibitory effect on q-HSC activation and transformation. We hypothesized that UA impact q-HSC activation and transformation by interfering with expression of NOX and Hh pathway components. This study aimed to address this possibility and to explore the underlying mechanisms by identifying changes in NOX and Hh pathway expression.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

The following reagents were used in this study: Pronase E (PE), Nycodenz, UA and diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Type IV collagenase and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). DNase I was purchased from Generay Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Recombinant human TGF-β1 was purchased from PeproTech, Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Antibodies against NOX2/gp91phox, p22phox, desmin, Rac1, sterol-4-alpha-methyl oxidase (Smo), Gli family zinc finger 2 (Gli2), and α-SMA were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Antibodies against p67phox and sonic hedgehog (Shh) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). An anti-β-actin antibody and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). RNA simple Total RNA kit, Real Master Mix, and FastQuant RT kit were purchased from Tiangen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Primers were synthesized by Beijing Genomics Institute (Beijing, China).

Animals

Healthy adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (age 12–16 weeks, weighing between 380 and 450 g) were purchased from SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Hunan, China) and housed in plastic cages containing wood shavings in a room at 25°C with a 24-h day/night cycle and free access to a standard laboratory diet and water. The animal study protocol was approved by The National Health and Family Planning Commission. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University.

Primary HSC isolation and identification

Primary quiescent HSCs were isolated by liver perfusion in situ and density gradient centrifugation. Perfusion was performed using D-Hanks buffer, protease E and collagenase IV. Centrifugation was performed with 28% Nycodenz. Trypan blue staining was performed to identify cellular activity. The purity and state (quiescent or activated) of the cells were determined by immune fluorescence, which was performed to observe intracellular expression of desmin and α-SMA, specific markers of quiescent and activated HSCs, respectively.

Cell culture and treatment

Fresh primary q-HSCs were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. After 48 h, the medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS; the medium was similarly replaced every 48 h. The HSCs were randomly divided into the following 5 groups on the fifth day: Blank control (cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS only), UA control (cultured in DMEM containing 40 µM UA), TGF-β1 (cultured in DMEM containing 5 µg/l TGF-β1), UA intervention (pretreated with medium containing 40 µM UA for 30 min and then stimulated with 5 µg/l TGF-β1), and DPI intervention (pretreated with 10 µM DPI (a NOX inhibitor) for 30 min and then stimulated with 5 µg/l TGF-β1). The cells were continuously cultured for 12 or 24 h before beginning the experiments.

Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Cells in each group were harvested 12 h after treatment. Total RNA was extracted according to RNA simple Total RNA kit and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using FastQuant RT kit. PCR was performed in 96 well plates with SuperRealPreMix Plus (SYBR-Green) kit. The final PCR volume was 20 µl, and the PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 62°C for 30 sec. β-Actin was used as an internal reference to determine the mRNA expression levels of α-SMA, type I collagen, Shh, Smo, and Gli2. The 2−ΔΔCq method was used to normalize values of gene expression. The primer sequences are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Amplified fragment (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| α-SMA | 175 | |

| Forward | CTCCCAGCACCATGAAGATCAA | |

| Reverse | GGGCGTGACTTAGAAGCATTTG | |

| Type-I collagen | 105 | |

| Forward | GGGGCAAGACAGTCATCGAA | |

| Reverse | GGATGGAGGGAGTTTACACGAA | |

| Shh | 133 | |

| Forward | ATTGGCACCTGGCTGTTGGA | |

| Reverse | GTTGCTTATCTGGCAGTCGCTTC | |

| Smo | 175 | |

| Forward | AGGCAGCCAGCAAGATCAAT | |

| Reverse | TCTTGGTAGGCAGCCCAATG | |

| Gli2 | 163 | |

| Forward | GGGTTCAGCCTTTGGACATACA | |

| Reverse | CGACTCGCTGTTCTGCTTATTCT | |

| β-actin | 150 | |

| Forward | CCCATCTATGAGGGTTACGC | |

| Reverse | TTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTC |

Shh, sonic hedgehog; Smo, sterol-4-alpha-methyl oxidase; Gli2, Gli family zinc finger 2; SMA, smooth muscle actin.

Western blotting analysis

After 24 h of drug treatment, total cellular protein was extracted from cells. The micro-bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method was used to determine the protein concentration. The proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane, and blocked in Tris-buffered saline with 5% skim milk and Tween-20 (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature. Next, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (1:1,000). After three washes, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody at 4°C for 4 h. The membranes were washed again, and complexes were visualized using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc™ XRS system. The gray values of the blots were analyzed using ImageLab 3.0. β-Actin was used as the internal control.

Statistical analysis

All measurement data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; the data were analyzed with SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago. IL, USA). Data with a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance were analyzed by univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the least significant difference (LSD) test; data without a normal distribution or with heterogeneity of variance were analyzed using a rank-sum test (Kruskal-Wallis H test or Nemenyi test). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

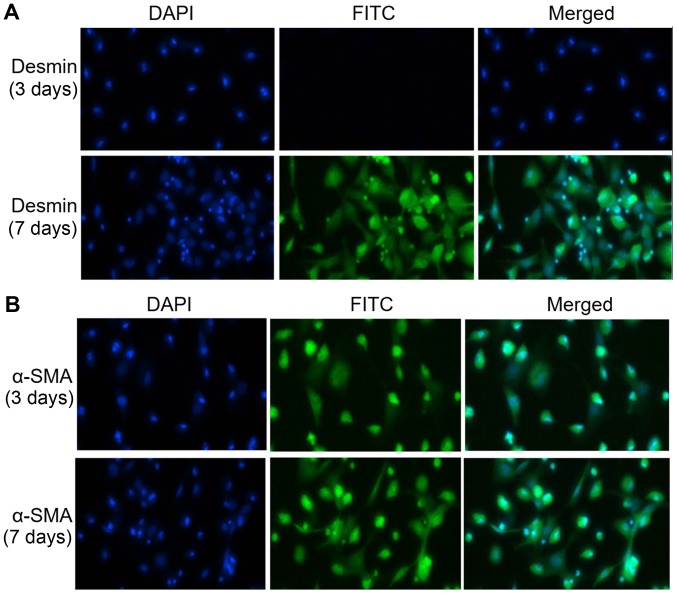

Successful extraction of primary q-HSCs

Primary q-HSCs were stained with 0.4% trypan blue after extraction from healthy SD rats, and microscopic examination revealed no staining in over 95% of cells. Based on immunofluorescence analysis, over 98% of the q-HSCs cultured without any treatment for 3 and 7 days exhibited desmin expression (Fig. 1A). Although the 3-day q-HSCs barely expressed α-SMA, 98% of the 7-day cell spositively expressed α-SMA (Fig. 1B), indicating that they were completely activated.

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence was used to detect desmin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression in primary quiescent hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) cultured for 3 or 7 days without treatment (desmin is a marker of quiescent HSCs; α-SMA is a marker of activated HSCs). (A) Desmin expression in primary quiescent HSCs cultured for 3 days or activated HSCs cultured for 7 days without treatment (magnification, ×400). (B) α-SMA expression in primary quiescent HSCs cultured for 3 days or activated HSCs cultured for 7 days without treatment (magnification, ×400).

UA inhibits q-HSC activation and transformation

Expression of α-SMA and synthesis of type I collagen are signs of q-HSC activation and transformation. Primary q-HSCs cultured for 3 days exhibit low levels of α-SMA mRNA and protein expression, though the level increases significantly after stimulation with TGF-β1 for 12 or 24 h. Pretreatment with UA or DPI decreases mRNA and protein expression of α-SMA (all P<0.05). Consistently, q-HSCs stimulated with TGF-β1 for 12 h showed enhanced expression of type I collagen, which was significantly downregulated by pretreatment with UA or DPI for 30 min before adding TGF-β1 (P<0.01) (Figs. 2–4). These results suggest that NOX mediates TGF-β1-induced activation and transformation of q-HSCs and that UA has an inhibitory effect on q-HSC activation and transformation.

Figure 2.

α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) mRNA expression and the effect of ursolic acid (UA) intervention during activation of quiescent hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). **P<0.01 vs. the control group; ##P<0.01 vs. the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 group. DPI, diphenyleneiodonium chloride.

Figure 4.

Type I collagen mRNA expression in each group. *P<0.05 vs. the control group; #P<0.05 vs. the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 group; ##P<0.01 vs. the TGF-β1 group. DPI, diphenyleneiodonium chloride.

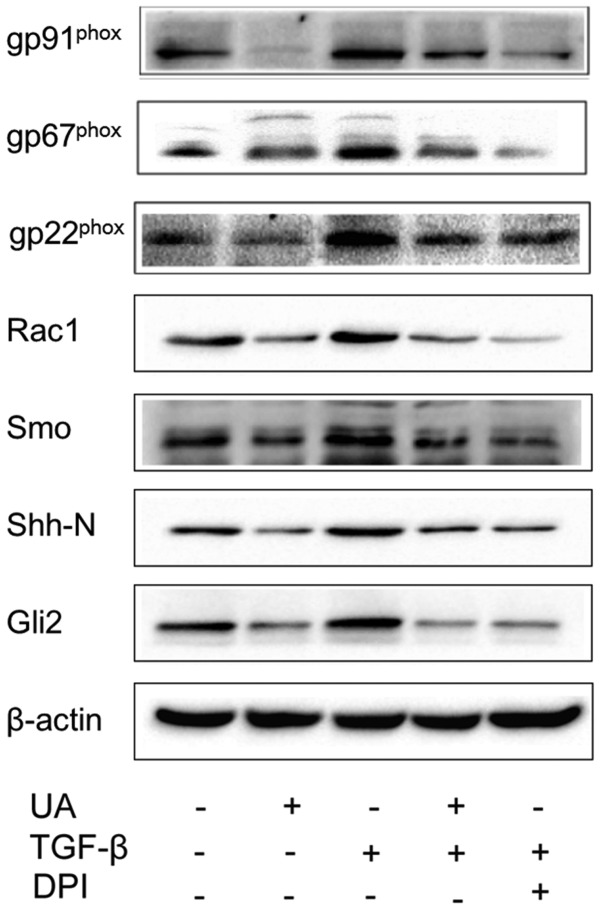

UA inhibits expression of NOX subunits during q-HSC activation and transformation

Western blotting analysis revealed low expression of NOX subunits, gp91phox, p67phox, p22phox and Rac1 in primary HSCs cultured for 3 days. However, after treatment with TGF-β1 for 24 h, the expression levels of gp91phox, p67phox, p22phox and Rac1 proteins were significantly higher than those in the control group (P<0.01). Moreover, pretreatment with UA downregulated expression of these NOX subunits (Fig. 5). These results demonstrate that UA inhibits expression of NOX subunits during q-HSC activation and transformation.

Figure 5.

Effect of ursolic acid (UA) on the NOX subunits and Hh signaling pathway during quiescent hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation. Quiescent HSCs were stimulated with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 (5 µg/l) for 24 h. Protein expression levels of gp91phox, p67phox, p22phox, Rac1, Shh, Smo, and Gli2 were significantly higher than in the control group. Treatment with UA (40 µM) inhibited expression of these proteins. UA and DPI had comparable effects. DPI, diphenyleneiodonium chloride; Shh, sonic hedgehog; Smo, sterol-4-alpha-methyl oxidase; Gli2, Gli family zinc finger 2.

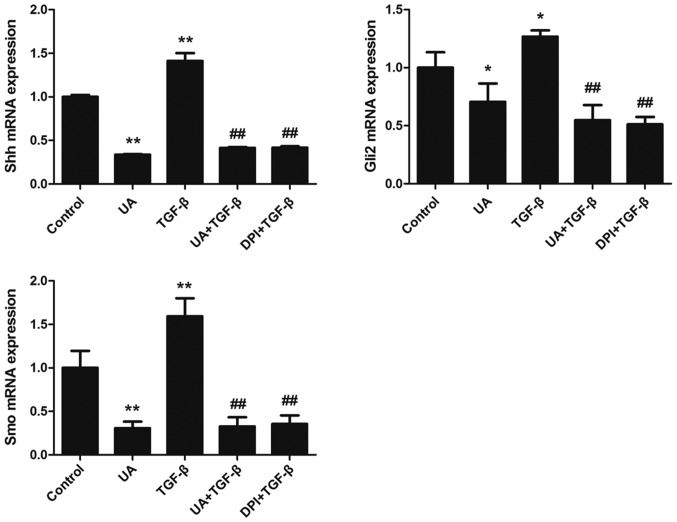

UA inhibits expression of Hh signaling pathway components during q-HSC activation and transformation

mRNA expression of Shh, Smo, and Gli2 in 3 day-cultured primary HSCs was evaluated by RT-PCR. Following stimulation with TGF-β1 for 12 h, the levels of Shh, Smo, and Gli2 mRNA expression were significantly increased, whereas pretreatment with UA or DPI reduced this expression (P<0.05). We further performed western blotting analysis and found that treatment with TGF-β1 for 24 h upregulated expression of Shh, Smo, and Gli2 proteins in 3 day-cultured primary q-HSCs. UA and DPI inhibited TGF-β1-induced protein expression of Shh, Smo, and Gli2. These results show that UA inhibited expression of Shh, Smo, and Gli2 at both the mRNA and protein levels, indicating that UA can block the Hh signaling pathway by inhibiting expression of NOX (Figs. 5 and 6).

Figure 6.

mRNA expression levels of Hedgehog (Hh) pathway components during quiescent hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation. Quiescent HSCs were stimulated with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 (5 µg/l) for 12 h. mRNA expression levels of Shh, Smo, and Gli2 were significantly higher than in the control group. Treatment with UA (40 µM) for 30 min and then stimulation with TGF-β1 (5 µg/l) inhibited mRNA expression of these genes. Ursolic acid (UA) and diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI) had comparable effects. *P<0.05 vs. the control group; **P<0.01 vs. the control group; ##P<0.01 vs. the TGF-β1 group.

Discussion

Inhibiting the activation of q-HSCs and their transformation into MFBs is a promising treatment strategy for preventing hepatic fibrosis. Since 2004, we have screened more than 20 monomers derived from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and first discovered that UA selectively induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation in activated HSCs without inducing liver cell apoptosis (8). In the present study, we demonstrated that UA inhibits q-HSC activation and transformation by suppressing TGF-β1-induced α-SMA and type I collagen expression in q-HSCs. The mechanisms for these effects likely involve inhibition of NOX and Hh signaling component expression.

NOX, a multi-component complex that catalyzes the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), is involved in pulmonary fibrosis, liver fibrosis, cancer and other diseases (11). Accumulating evidence suggests a critical role for NOX in the activation of hepatic MFBs (12). As NOX-derived ROS are implicated in regulating HSC activation and hepatocyte apoptosis, both of which are essential steps for initiating liver fibrosis (12–14), NOX is a promising target for anti-fibrosis therapy (15). The Hh signaling pathway has an important role in q-HSC activation and transformation (16). Furthermore, studies have shown that activation of Rac1 promotes Hh-mediated acquisition of the myofibroblastic phenotype in rat and human HSCs (7). Furthermore, the NOX1/4 dual inhibitor GKT137831 suppressed ROS production as well as inflammatory and proliferative genes induced by Shh in primary mouse HSCs (1). Thus, NOX may be involved in regulating Hh signaling (17).

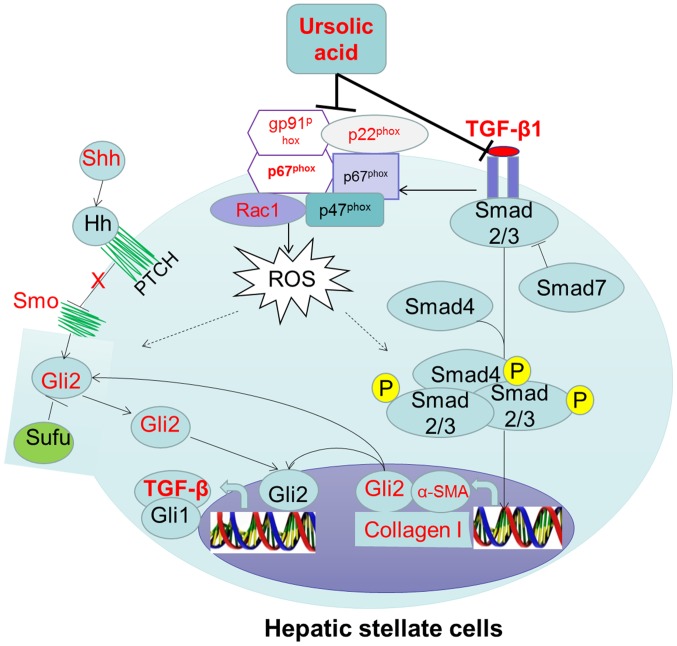

In the present study, we demonstrated that UA downregulated expression of NOX subunits and Hh pathway components (Shh, Smo, and Gli2) at both the mRNA and protein levels. These results suggest that UA inhibits expression of NOX and Hh signaling genes during q-HSC activation and transformation. To further ascertain whether UA indirectly inhibits Hh signaling pathway activation by affecting NOX, q-HSCs were pretreated with DPI before stimulation with TGF-β1. We found that DPI can reduce Shh, Smo, and Gli2 expression, a result that demonstrates that NOX is involved in regulating the Hh signaling pathway during activation of q-HSCs. NOX derived ROS may regulate the activation of the Hh signaling pathway, as studies have shown that hypoxia-induced ROS mediated activation of the Hh signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer cells (18). In addition, We hypothesized that UA may inhibit the TGF-β1 induced Hh signaling activation. Because research showed that UA is an antagonist for TGF-β1 (19). There have a cross talks between the TGF-β and Hh pathway in cancer, Gli2 is a direct target genes of TGF-β/SMAD signal transduction (20,21).

In summary, TGF-β1-induced q-HSC activation and transformation can be inhibited by UA. We speculate that the mechanism is, on the one hand, UA inhibit the TGF-β1 induced Hh signaling activation as an antagonist of TGF-β1, on the another hand, by inhibiting expression of NOX subunits (Fig. 7), which represents the most likely mechanism of the effect of UA on q-HSC activation and transformation.

Figure 7.

Summary of the study results with pathway.

Figure 3.

α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) protein expression and the effect of ursolic acid (UA) intervention during activation of quiescent hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). α-SMA protein expression increases significantly after stimulation with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 (5 µg/l) for 24 h. Pretreatment with UA (40 µM) or DPI (10 µM) decreases protein expression of α-SMA. DPI, diphenyleneiodonium chloride.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 81160061 and 81260082).

References

- 1.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI200524282C1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puche JE, Saiman Y, Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:1473–1492. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray K. Liver: Hepatic stellate cells hold the key to liver fibrosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:74. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sancho P, Mainez J, Crosas-Molist E, Roncero C, Fernández-Rodriguez CM, Pinedo F, Huber H, Eferl R, Mikulits W, Fabregat I. NADPH oxidase NOX4 mediates stellate cell activation and hepatocyte cell death during liver fibrosis development. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swiderska-Syn M, Syn WK, Xie G, Krüger L, Machado MV, Karaca G, Michelotti GA, Choi SS, Premont RT, Diehl AM. Myofibroblastic cells function as progenitors to regenerate murine livers after partial hepatectomy. Gut. 2014;63:1333–1344. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi SS, Witek RP, Yang L, Omenetti A, Syn WK, Moylan CA, Jung Y, Karaca GF, Teaberry VS, Pereira TA, et al. Activation of Rac1 promotes hedgehog-mediated acquisition of the myofibroblastic phenotype in rat and human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2010;52:278–290. doi: 10.1002/hep.23649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen YM, Zhu X, Zhang KH, Xie Y, Chen J, Dai Y, Ou-Yang CH, Li BM. Effect of ursolic acid on proliferation and apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells in vitro. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2008;16:298–301. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Ikejima K, Kon K, Arai K, Aoyama T, Okumura K, Abe W, Sato N, Watanabe S. Ursolic acid ameliorates hepatic fibrosis in the rat by specific induction of apoptosis in hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2011;55:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He W, Shi F, Zhou ZW, Li B, Zhang K, Zhang X, Ouyang C, Zhou SF, Zhu X. A bioinformatic and mechanistic study elicits the antifibrotic effect of ursolic acid through the attenuation of oxidative stress with the involvement of ERK, PI3K/Akt, and p38 MAPK signaling pathways in human hepatic stellate cells and rat liver. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:3989–4104. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S85426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paik YH, Brenner DA. NADPH oxidase mediated oxidative stress in hepatic fibrogenesis. Korean J Hepatol. 2011;17:251–257. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2011.17.4.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang S, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. The role of NADPH oxidases (NOXs) in liver fibrosis and the activation of myofibroblasts. Front Physiol. 2016;7:17. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang L, Wang Y, Mao H, Fleig S, Omenetti A, Brown KD, Sicklick JK, Li YX, Diehl AM. Sonic hedgehog is an autocrine viability factor for myofibroblastic hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2008;48:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Syn WK, Oo YH, Pereira TA, Karaca GF, Jung Y, Omenetti A, Witek RP, Choi SS, Guy CD, Fearing CM, et al. Accumulation of natural killer T cells in progressive nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:1998–2007. doi: 10.1002/hep.23599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crosas-Molist E, Fabregat I. Role of NADPH oxidases in the redox biology of liver fibrosis. Redox Biol. 2015;6:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi SS, Omenetti A, Witek RP, Moylan CA, Syn WK, Jung Y, Yang L, Sudan DL, Sicklick JK, Michelotti GA, et al. Hedgehog pathway activation and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions during myofibroblastic transformation of rat hepatic cells in culture and cirrhosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G1093–G1106. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00292.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lan T, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. Deficiency of NOX1 or NOX4 prevents liver inflammation and fibrosis in mice through inhibition of hepatic stellate cell activation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W, Cao L, Chen X, Lei J, Ma Q. Resveratrol inhibits hypoxia-driven ROS-induced invasive and migratory ability of pancreatic cancer cells via suppression of the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:1718–1726. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami S, Takashima H, Sato-Watanabe M, Chonan S, Yamamoto K, Saitoh M, Saito S, Yoshimura H, Sugawara K, Yang J, et al. Ursolic acid, an antagonist for transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1. FEBS Lett. 2004;566:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perrot CY, Javelaud D, Mauviel A. Overlapping activities of TGF-β and Hedgehog signaling in cancer: Therapeutic targets for cancer treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;137:183–199. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Javelaud D, Alexaki VI, Dennler S, Mohammad KS, Guise TA, Mauviel A. TGF-β/SMAD/GLI2 signaling axis in cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5606–5610. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]