Abstract

Objective

To assess effectiveness of partial versus total tonsillectomy in children.

Data Sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library from January 1980 – June 2016.

Review Methods

Two investigators independently screened studies and extracted data. Investigators independently assessed risk of bias and strength of evidence of the literature. Heterogeneity precluded quantitative analysis.

Results

In 16 eligible randomized controlled trials (RCTs), definitions of “partial” tonsillectomy varied. In addition to comparing partial with total tonsil removal, 11 studies compared surgical techniques (e.g., coblation). In studies comparing the same technique, return to normal diet or activity was faster with partial removal (more favorable outcomes in 4/4 RCTs). In studies with differing surgical techniques, return to normal diet and activity were faster with partial versus total tonsillectomy (more favorable outcomes in 5/6 studies). In 3 of 4 RCTs, partial tonsillectomy was associated with more throat infections than total. Differences between groups were generally not statistically significant for obstructive symptom persistence, quality of life, or behavioral outcomes. Across all studies, 10 of roughly 166 children (6%) had tonsillar regrowth after partial tonsillectomy.

Conclusions

Data do not allow firm conclusions regarding the comparative benefit of partial versus total removal; however, neither surgical technique or extent of surgery appear to affect outcomes markedly. Partial tonsillectomy conferred moderate advantages in return to normal diet/activity but was also associated with tonsillar regrowth and symptom recurrence. Effects may be due to confounding given differences in populations and surgical approaches/techniques. Heterogeneity and differences in the operationalization of “partial” tonsillectomy limited comparative analyses.

Keywords: tonsillectomy, adenotonsillectomy, tonsillotomy

INTRODUCTION

Tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy (“tonsillectomy”) represent more than 15 percent of all surgical procedures in children under the age of 15 years in the United States.1,2 The primary indication for tonsillectomy has shifted over the last 20 years from recurrent throat infections to obstructive sleep-disordered breathing (OSDB), 3,4 broadly defined as breathing difficulties during sleep including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and upper airway resistance syndrome.. Tonsillectomy conventionally involves total removal of the tonsils, but partial tonsillectomy (also called tonsillotomy or intracapsular tonsillectomy) has been increasingly advocated as tonsillectomy indications have changed.5–9 Partial tonsillectomy entails sub-total removal of tonsillar tissue, leaving a margin of tissue on the tonsillar capsule, which may speed healing and reduce pain and inflammation.9 Proponents of partial tonsillectomy report lower rates of bleeding compared with total tonsillectomy and less pain, but the procedure may be associated with tonsillar regrowth and potential return of symptoms requiring reoperation.10–12

In this systematic review we examined the published evidence regarding the effectiveness of partial tonsillectomy compared with total tonsillectomy for children undergoing surgery for OSDB or recurrent throat infection. This review is a component of an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)-commissioned comparative effectiveness review of tonsillectomy in children conducted by the Vanderbilt Evidence-Based Practice Center. The full comparative effectiveness review13 and review protocol (PROSPERO registry number: CRD42015025600) are available at http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov.

METHODS

Information Sources and Eligibility Criteria

We searched the MEDLINE database via PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library from January 1980 to June 2016 using a combination of controlled vocabulary and key terms related to partial and total tonsillectomy (e.g., tonsillectomy, adenotonsillectomy, tonsillotomy). We also hand-searched the reference lists of included articles and recent reviews addressing tonsillectomy in children to identify potentially relevant articles. Complete search strategies are available in the full review.13

We developed inclusion criteria in consultation with an expert panel of clinicians and researchers (e.g., pediatric otolaryngologists, sleep experts). We included prospective, comparative studies (e.g., randomized controlled trials [RCTs], prospective cohort studies) to address effectiveness outcomes. We limited inclusion to English language studies after our preliminary scan identified few eligible non-English abstracts and studies published after 1999.

Data Extraction and Analysis

One team member initially extracted study design, study population characteristics (age, sex, tonsillectomy indication, etc.), intervention characteristics (surgical type and technique), and baseline and outcome data on constructs of interest (sleep, cognitive or behavioral, and health outcomes including OSDB symptoms and throat infections; tonsillar regrowth; return to usual diet or activity; from eligible studies. The current report addresses only effectiveness outcomes; we report data on post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage in a separate publication.14 A second investigator independently verified the accuracy of the extraction and revised as needed. We synthesized studies qualitatively and report descriptive statistics in summary tables as study interventions and outcomes were too heterogeneous to permit meta-analysis.

Assessment of Study Quality and Strength of Evidence

Two investigators independently evaluated the risk of bias of studies using prespecified questions appropriate for specific study designs.15 Senior reviewers resolved discrepancies in risk of bias assessment. We did not include studies with high risk of bias in our descriptive analyses.

Two investigators also graded the strength of the body of evidence (confidence in the estimate of effect) using methods based on the Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.16 We determined the strength of evidence (SOE) separately for major intervention-outcome pairs using a prespecified approach described in detail in the full review.13

RESULTS

We identified 16 unique RCTs with low or moderate risk of bias addressing partial tonsillectomy compared with total tonsillectomy.17–35 Table 1 outlines risk of bias and key outcomes reported. Study participants (n=1,234) ranged in age from 2 to 16 years. Across studies, definitions of “partial” tonsillectomy varied or were not explicit. Four studies explicitly noted leaving from 10 to 70 percent of the tonsil intact,18,20,22,28 while others noted leaving a thin rim of tissue or removing the bulk of the tonsil,19,21,23,24 and yet others reported removing the obstructive or protruding portion of the tonsil only.26,27,29–31 Six studies did not describe the portion of tissue removed.17,25,32–35

Table 1.

Overview of studies comparing partial vs. total tonsillectomy

| Characteristic | N RCTs |

|---|---|

| Comparisons | |

| Total cold dissection vs. partial cold dissection | 3 |

| Total coblation vs. partial coblation | 1 |

| Total electrocautery vs. partial electrocautery | 1 |

| Partial vs. total | 11 |

| Surgical Indication | |

| OSDB | 13 |

| Throat Infection | 0 |

| OSDB+Throat Infection | 2 |

| Not specified | 1 |

| Effectiveness Outcomes Frequently Reported | |

| Return to normal diet or activity | 10 |

| Number of throat infections | 5 |

| Tonsillar regrowth | 4 |

| Risk of Bias | |

| Low | 5 |

| Moderate | 11 |

| Region of Conduct | |

| North America | 8 |

| Europe | 4 |

| Asia | 3 |

| Africa | 1 |

| Total N participants | 1,234 |

Abbreviations: n = Number; OSDB = Obstructive Sleep-Disordered Breathing; RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial

In addition to comparing partial with total tonsil removal, over half of the studies also compared surgical techniques including microdebrider, laser, coblation, and electrocautery partial tonsillectomy and cold dissection, coblation, and electrocautery total tonsillectomy. In studies comparing both extent of surgical removal (i.e., partial vs. total removal) and different surgical techniques (e.g., partial coblation vs. total electrocautery), it is not possible to determine whether effects are due to the technique or due to the extent of surgery. Thus, except for in those studies that compared partial or total removal of the tonsils using the same technique (e.g., partial cold dissection vs. total cold dissection), we considered the comparison of interest broadly as partial vs. total tonsil removal. We present results by partial vs. total cold dissection, partial vs. total coblation or vs. electrocautery; and partial vs. total tonsillectomy regardless of technique.

Partial Cold Dissection vs. Total Cold Dissection Tonsillectomy

Return to Normal Diet

Few studies comparing total and partial cold dissection reported the same outcomes.18,20,22 (Table 2). Children who underwent partial tonsillectomy had significantly faster return to normal diet in two RCTs addressing this outcome (p values<0.001).18,22

Table 2.

Comparative effectiveness outcomes in studies addressing partial vs. total tonsillectomy

| Author, Year Study Design Risk of Bias |

Comparison Groups (n) | OSDB persistence | Tonsillar Regrowth | Return to Normal Diet or Activity | Throat Infections | Quality of Life | Behavioral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaidas 201318 RCT Low ROB |

G1: Partial cold tonsillectomy (50) G2: Total cold tonsillectomy (51) |

Snoring (6-years post-tonsillectomy) G1: 13/43 (30.2) G2: 12/48 (25) G1 vs. G2: p=NS Episodes of apnea (6-years post-tonsillectomy) G1: 2/43 (4.7) G2: 0 (0) G1 vs. G2: p=NS |

Tonsillar regrowth, 6 years post-surgery, n (%) G1: 6/13 (46.2) G2: NA Tonsillar regrowth requiring revision surgery, n (%) G1: 2/13 (5) G2: 0 |

Time to return to normal diet, mean days ± SD G1: 3.8 ± 0.2 G2: 7.1 ± 0.3 G1 vs.G2: P < 0.001 |

At least 1 episode of tonsillitis/year, 1–6 years post-tonsillectomy, n (%) G1: 5 (11.6) G2: 0 G1 vs. G2: p= NR Number throat infections/year, 1–6 years post-tonsillectomy, median (IQR) G1: 0 (0–1) G2: 0 (0–1) G1 vs. G2: p=NS |

NR | NR |

| Korkmaz 200820 RCT Moderate ROB |

G1: Partial cold tonsillectomy (40) G2: Total cold tonsillectomy (41) |

NR | Tonsillar regrowth within 2-years post-tonsillectomy, n G1+G2: 0/68 |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Skoulakis 200722 RCT Moderate ROB |

G1: Partial cold tonsillectomy (15) G2: Total cold tonsillectomy (15) |

NR | NR | Time to return to normal diet G1: 4 days earlier than G2 G1 < G2: p < 0.001 |

NR | NR | NR |

| Chang 200821 RCT Moderate ROB |

G1: Partial coblation tonsillectomy (34) G2: Total coblation tonsillectomy (35) |

NR | NR | Mean % of normal diet resumed (POD1–2) G1: 56 G2: 42 G1 vs.G2: p = 0.05 Mean % of normal diet resumed (POD5–6) G1: 73 G2: 48 G1 vs.G2: p < 0.05 Mean % of normal activity resumed (POD1–2) G1: 65 G2: 49 G1 vs.G2: p = 0.031 Mean % of normal activity resumed NR NR (POD5–6) G1: 84 G2: 64 G1 vs.G2: p = 0.002 |

NR | NR | NR |

| Park 200723 RCT Low ROB |

G1: Partial electrocautery tonsillectomy (19) G2: Total electrocautery tonsillectomy (21) |

NR | NR | Time to return to normal activity G1 vs.G2: p = NS |

NR | NR | NR |

| Chan 200428 RCT Moderate ROB |

G1: Partial tonsillectomy-coblation (27) G2: Total tonsillectomy-electrocautery (28) |

Worsening of obstructive symptoms (3-months post-tonsillectomy), n (%) G1: 10/21 (48) G2: 6/19 (25) p=NR Improvement in obstructive symptoms (12 months post-tonsillectomy) G1 vs. G2: p=NS |

NR | Time to return to normal diet, median days G1: 4.4 G2: 7.5 G1 vs.G2: p = NR Time to return to normal activity, median days G1: 4.1 G2: 8 G1 vs.G2: p = NR |

Incidence of sore throat or antibiotic use (3 and 12 months post-tonsillectomy) G1 vs. G2: p=NS |

NR | NR |

| Ericsson 200926,27 RCT Moderate ROB |

G1: Partial tonsillectomy-coblation (35) G2: Total tonsillectomy-cold dissection (32) |

Persistence of snoring 6-months post-tonsillectomy Greater number of children in G1 vs. G2 had snoring, p < 0.05 24-months post-tonsillectomy G1 vs. G2; p=NS Total tonsillectomy for OSDB-symptom persistence, n (%) G1: 2/35 (5.7) G2: NA |

NR | Time to return to normal diet G1: 4 days earlier than G2 G1 vs. G2: p=NS Time to return to normal activity G1: 3 days earlier than G2 G1 vs. G2: p=NS |

Sore throats requiring antibiotics, 6-months post-tonsillectomy, n G1: 4 G2: 2 G1 vs. G2: p=NS Sore throats requiring antibiotics, 24-months post-tonsillectomy, n G1: 8 G2: 1 G1 vs. G2: p= NR |

OSA-18 (Total) Change score 6-months post-tonsillectomy G1: 1.8±1.2 G2: 1.8±1.0 G1 vs. G2: p=NS Change score 24-months post-tonsillectomy G1: 1.8±1.2 G2: 1.9±1.4 G1 vs. G2: p=NS Disease-specific quality of life data in figures only |

Child Behavior Checklist, Total Score 6-months post-tonsillectomy G1: 19.5 ±18.4 G2: 13.5 ±9.8 G1 vs. G2: p=NS 24-months post-tonsillectomy G1: 13.9±12.9 G2: 13.6±21.7 G1 vs. G2: p=NS |

| Hultcrantz 200429–31 RCT Moderate ROB |

G1: Partial tonsillectomy-coblation (49) G2: Total tonsillectomy-cold dissection (43) |

Persistence of snoring 12-months and 3-years post-tonsillectomy No difference in frequency or loudness of snoring between groups Presence of apnea, 1–3 years post-tonsillectomy G1: 0 G2: 0 |

Total tonsillectomy for OSDB-symptom persistence, n G1: 1 (denominator not clear, 91 children in both groups assessed at 1 year) G2: NA |

NR | Sore throats requiring antibiotics, 12-months post-tonsillectomy, n G1: 6 G2: 4 G1 vs. G2: p=NS Sore throats requiring antibiotics, 1–3 years post-tonsillectomy, n G1: 6 G2: 5 G1 vs. G2: p=NS |

Glasgow Children’s Benefit Inventory, % 33 months post-tonsillectomy Overall QoL-Much better G1: 61 G2: 79 Overall QoL-A little better G1: 35 G2: 18 Overall QoL-No change G1: 5 G2: 3 G1 vs. G2: all p=NS |

Child Behavior Checklist, Total Score 12-months post-tonsillectomy No differences in degree of improvement between groups Glasgow Children’s Benefit Inventory, % 33 months post-tonsillectomy Behavior-Much better G1: 19 G2: 10 Behavior-A little better G1: 19 G2: 15 Behavior-No change G1: 62 G2: 74 G1 vs. G2: all p=NS |

| Chang 200524 RCT Moderate ROB |

G1: Partial tonsillectomy-coblation (52) G2: Total tonsillectomy- electrocautery (49) |

NR | NR | Mean % of normal diet resumed (POD1–2) G1: 49 G2: 30 G1 vs.G2: p < 0.005 Mean % of normal diet resumed (POD5–6) G1: 74 G2: 42 G1 vs.G2: p < 0.005 Mean % of normal activity resumed (POD1–2) G1: 53 G2: 42 G1 vs.G2: p = NS Mean % of normal activity resumed (POD5–6) G1: 82 G2: 56 G1 vs.G2: p < 0.005 |

NR | NR | NR |

| Coticchia 200634 RCT Moderate ROB |

G1: Partial tonsillectomy-coblation (13) G2: Total tonsillectomy-cold (10) |

NR | NR | N children resuming normal diet by POD7, (%) G1: 11 (85) G2: 0 (0) G1 vs.G2: p = NR |

NR | NR | NR |

| Derkay 200632 RCT Low ROB |

G1: Partial tonsillectomy-microdebrider (150) G2: Total tonsillectomy-electrocautery (150) |

NR | NR | Time to return to normal diet, median days (Q1 – Q3) G1: 3 (1.5–6) G2: 3.5 (1.5–6.5) G1 vs.G2: p = NS Time to return to normal activity, median days(Q1 – Q3) G1: 2.5 (1–5) G2: 4 (2.5–6.5) G1 vs.G2: p < 0.01 |

NR | Baseline to postoperative changes, 1 month post-tonsillectomy G1 vs. G2: p=NS Decrease in emotional distress G1>G2: p < 0.01 Decrease in activity limitation G1>G2: p < 0.01 |

NR |

| Beriat 201333 RCT Moderate ROB |

G1: Partial tonsillectomy- microdebrider (37) G2: Total tonsillectomy- cold dissection (45) |

NR | NR | NR | Recurrent throat infection (within 12-months post-tonsillectomy), n G1: 2 G2: 0 G1 vs. G2: p= NR |

NR | NR |

Abbreviations: G = Group; N = Number; NA = Not Applicable; NR = Not Reported; NS = Not Significant; OSDB = Obstructive Sleep Disordered Breathing; RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial; ROB = Risk of Bias; SD = Standard Deviation

Tonsillar Regrowth and Reoperation

In one RCT including 40 children with OSDB undergoing partial tonsillectomy and 41 undergoing total, no children had tonsillar regrowth (0 of 68 followed up) in the 2-year followup period.20 In a second RCT, 6 out of 43 children undergoing partial tonsillectomy and followed for 6 years had regrowth, in two cases requiring total tonsillectomy.18

Other Outcomes

In one RCT, children in both partial and total tonsillectomy groups had recurrence of snoring; differences were not statistically significant between groups.18 No children (0/91) in either group had throat infections (not precisely defined) in the 6-year follow-up period, although the study reported that five children in the partial tonsillectomy arm had at least one episode of “tonsillitis” per year in the followup period.18

Partial Coblation or Electrocautery vs. Total Coblation or Electrocautery

Two small RCTs reported only on return to usual diet or activity. In the coblation study, children in the partial tonsillectomy group consumed a significantly greater percentage of their normal diet and were engaged in a greater portion of their normal activity than were children in the total tonsillectomy group at all time points assessed.21 In the one study comparing partial vs. total electrocautery, differences in return to normal activity were not statistically significantly different between groups.23

Partial Tonsillectomy vs. Total Tonsillectomy with Mixed Surgical Approaches

Among the 11 studies addressing partial vs. total tonsillectomy without using the same surgical technique, eight (reported in multiple publications) addressed effectiveness outcomes (Table 2) 24,26–35 and three 17,19,25 reported only postoperative bleeding (addressed in a separate publication14). As with the studies outlined above, few RCTs addressed the same outcomes. Because these studies differ in both extent of surgery and surgical technique, it is difficult to isolate the effect of partial tonsillectomy.

Return to Normal Diet or Activity

RCTs addressing these outcomes were typically small (< 100 children) with short-term followup and variable assessment methods (e.g., mean days, mean percentage, number of children).24,26–28,32,34,35 In all six studies addressing return to normal diet, children receiving partial tonsillectomy had more favorable outcomes compared with those receiving total tonsillectomy. Two studies reported that children undergoing partial surgeries either consumed a significantly greater proportion of their normal diet24 or returned to normal diet in fewer days35 than did children in total tonsillectomy arms. Four RCTs reported faster return in the partial tonsillectomy groups or greater numbers of children consuming a normal diet after partial compared with total tonsillectomy, but differences were not statistically significant26,27,32 or significance was not assessed.28,34

Tonsillar Regrowth

Two RCTs reported low rates of tonsillar regrowth after partial tonsillectomy.26,27,29–31 Out of an estimated 126 children providing followup data, three (2.4%) reported regrowth and had total tonsillectomy.

OSDB Persistence

Three RCTs (in multiple publications) addressed outcomes related to the persistence of OSDB.26–31 In two, obstructive symptoms including snoring worsened in the short term in the partial tonsillectomy groups compared with total tonsillectomy, but differences between groups were not significant at longer-term follow-up (12–24 months post-tonsillectomy). In the third RCT, no children in either group had snoring or apnea at 1 and 3 years postoperatively.29–31

Five RCTs addressed return to normal activity.24,26–28,32,35 As with diet, in all studies children undergoing partial tonsillectomy had a faster return to normal activity or engaged in a greater percentage of normal activity than did children who had total tonsillectomy. Differences were statistically significant in two RCTs.24,32

Throat Infections

Four RCTs addressed recurrent throat infections.26–31,33 In three of the four RCTs, children in the partial tonsillectomy groups had more throat infections than did those receiving total tonsillectomy, though differences were typically not statistically significant.26–31

Quality of Life

Three RCTs assessed quality of life using different scales and at different time points.26,27,29–32 In one study with assessment at 1-month post-surgery, changes in physical suffering, sleep disturbances, speech issues, or caregiver concerns did not differ significantly between groups, but decreases in emotional distress and in activity limitations were greater in the partial tonsillectomy arm than in the total tonsillectomy arm.32 In two additional studies (one using the OSA-18 and one using the Glasgow Children’s Benefit Inventory [GCBI]), both groups improved from baseline, and changes in quality of life were not significantly different between groups. In one study, more than 30% of children in both groups had large improvements in disease-specific quality of life at 6 months and 2 years post-surgery, but group differences were not significant.26,27

Behavioral Outcomes

In RCTs reported changes in behavior using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), both groups improved from baseline overall and in each domain assessed (internalization, externalization), with no significant differences between groups in the short or longer (≥12 months) term.26,27,29–31 One study assessing behavior changes with the GCBI also reported no significant differences between groups.29–31

Other Outcomes

In one RCT, a repeat partial tonsillectomy in a child with pre-existing enuresis and encopresis, which was temporarily improved by the index partial tonsillectomy, did not improve encopresis.26,27 Another reported that 7 children undergoing total tonsillectomy and 3 undergoing partial had baseline enuresis, which improved in nine children (treatment group not specified) postoperatively.29–31

Strength of the Evidence (SOE)

Overall, we did not find strong or consistent evidence to support firm conclusions about effects or partial or total tonsillectomy (Table 3). Return to normal diet was faster (roughly 4 days) in children who underwent partial tonsillectomy in studies comparing partial and total cold dissection tonsillectomy. Our confidence in this conclusion was low (low SOE). We could not assess effects on OSDB persistence or on effects on throat infections in these studies (insufficient SOE). Similarly, in studies comparing either partial and total coblation or partial and total electrocautery tonsillectomy, we could not make conclusions about effects on return to normal diet or activity (insufficient SOE).

Table 3.

Summary of evidence in studies addressing effectiveness and harms of tonsillectomy techniques

| Intervention and comparator | Number/Type of Studies (Total N Participants) | Key Outcome(s) | Strength of Evidence (SOE) Grade | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total vs. partial cold dissection tonsillectomy | 2 RCT18,22 (131) | Return to normal diet | Low SOE for faster return to normal diet after partial vs. total tonsillectomy | Children undergoing partial tonsillectomy returned to normal diet approximately 4 days sooner than children undergoing total tonsillectomy according to parent report |

| 1 RCT18 (101) | Throat infection, OSDB persistence | Insufficient SOE | Insufficient data to assess effects on throat infections given single, small study | |

| Partial vs. total coblation tonsillectomy | 1 RCT21 (69) | Return to normal diet or activity | Insufficient SOE | Insufficient data to assess effects on return to normal diet or activity given single, small study |

| Partial vs. total electrocautery tonsillectomy | 1 RCT23 (40) | Return to normal activity | Insufficient SOE | Insufficient data to assess effects on return to normal diet or activity given single, small study |

| Total vs. partial tonsillectomy (mixed techniques) | 6 RCT24,26–28,32,34,35 (620) | Return to normal diet or activity | Low SOE for more favorable return to normal diet and activity in children undergoing partial vs. total tonsillectomy | Children undergoing partial vs. total tonsillectomy had consistently more favorable outcomes but unit of measure varied across studies (e.g., mean days, N children) |

| 3 RCT26–31 (214) | OSDB persistence | Low SOE for no difference in effects on long-term persistence of OSDB symptoms between partial and total tonsillectomy | More children undergoing partial vs. total tonsillectomy had short-term snoring or obstructive symptoms in 2 studies but no group differences in longer term in any study | |

| 2 RCT26,27,29–31 (159) | Quality of Life (≥12 months post-tonsillectomy) | Low SOE for no long-term differences in quality of life after partial vs. total tonsillectomy | Improvements from baseline in both groups in 2 small studies, but no significant group differences in quality of life in either study | |

| 2 RCT26,27,29–31 (159) | Behavioral Outcomes (≥12 months post-tonsillectomy) | Low SOE for no long-term differences in behavioral outcomes after partial vs. total tonsillectomy | Improvements from baseline in both groups on the Child Behavior Checklist in 2 small studies, but no significant group differences in either study | |

| 4 RCT26–31,33 (296) | Throat Infections (≥12 months post-tonsillectomy) | Low SOE for no effect on throat infections following partial vs. total tonsillectomy | More throat infections or sore throats following partial vs. total tonsillectomy in 3 of 4 RCTs but no significant group differences |

Abbreviations: N=number; OSDB=obstructive sleep disordered breathing; RCT= randomized controlled trial; SOE=strength of evidence

In studies comparing mixed techniques for partial or total tonsillectomy, return to normal diet and activity were more favorable in children undergoing partial versus total tonsillectomy (roughly 1–4 days faster). Our confidence in these conclusions was low (low SOE). We found no difference in effects on long-term (>12 months) persistence of OSDB symptoms, quality of life, behavioral outcomes, or throat infections between partial and total tonsillectomy in these studies (low SOE).

DISCUSSION

Data from the studies identified for this review do not allow firm conclusions about the benefits or harms of one technique over another or about the comparative benefit of partial vs. total removal; however, neither surgical technique or extent of surgery appeared to have a marked effect on outcomes. Few studies compared partial and total tonsillectomy using the same surgical technique.18,20–23 In those that did, return to normal diet or activity was faster in children undergoing partial removal (more favorable outcomes in 4/4 RCTs). In studies evaluating partial vs. total tonsillectomy using differing surgical techniques, children receiving partial tonsillectomy generally had a faster return to diet (more favorable outcomes in 6/6 studies) and normal activity (more favorable outcomes in 5/6 studies) compared with those receiving total tonsillectomy; however, these effects may be due to confounding by indication or surgical technique (e.g., coblation, cold dissection) as both varied across studies. Differences between partial and total tonsillectomy groups were generally not statistically significant for outcomes related to OSDB persistence, quality of life, or behavior (although it is not possible to be certain that effects are due to the surgical technique rather than the extent of surgery) in these studies.

These findings largely align with those reported in other recent evidence syntheses comparing partial and total tonsillectomy. Two reviews or meta-analyses evaluated partial vs. total tonsillectomy (using any technique) for the management of sleep-disordered breathing in children.6,36 In both, partial tonsillectomy was associated with lower PTH rates, and one meta-analysis reported no differences in longer-term quality of life or resolution of obstructive symptoms between groups (mean length of follow-up=22 months).36 Acevedo and colleagues evaluated studies including children and adults undergoing tonsillectomy for any indication and reported lower PTH rate and faster return to normal diet associated with partial tonsillectomy and limited data to assess rates of tonsillar regrowth.7

While partial tonsillectomy is associated with some improved outcomes in the short term, it may also be associated with tonsillar regrowth that can lead to recurrent symptoms. Across all studies included in this review, 10 out of an estimated 166 children (6%) had tonsillar regrowth after partial tonsillectomy, 5 of whom ultimately underwent revision surgery. This regrowth rate is somewhat higher than those reported in other large studies.10,12 “Regrowth,” or the association of regrowth with clinical symptoms, were typically not precisely defined in studies. Need for reoperation, however, may serve as a proxy for symptomatic regrowth. In one registry study specifically examining the rate of reoperation following partial vs. total tonsillectomy, risk of reoperation was greater after partial tonsillectomy (hazard ratio=7.16, 95% CI: 5.52 to 9.13).10 Seventy-five of 11,741 (0.6%) children who underwent total tonsillectomy required reoperation compared with 609 of 15,794 who underwent partial (3.9%, p<0.0001). The most common indication for reoperation after either type of tonsillectomy was upper airway obstruction (80% of cases). Similarly, one meta-analysis reported a significant risk of recurrence of obstructive symptoms after partial tonsillectomy at a mean of 31 months of follow-up (risk ratio of 3.33 [95% CI: 1.62 to 6.82, p = 0.001]).11

Limitations

Findings in this review are limited by inclusion of English language studies only, though our preliminary assessment of non-English studies identified few of relevance. We also did not include retrospective studies or studies without a comparison group. While prospective, comparative studies are generally subject to less risk of bias, we recognize that retrospective studies or case series may have contributed data on longer-term effects of partial tonsillectomy. Limitations of the evidence base include significant heterogeneity in populations and surgical techniques and a lack of long term follow-up. Study samples were typically not clearly characterized; thus it is difficult to understand potential effects of baseline severity of surgical indication or comorbidities on outcomes. Similarly, few studies compared partial or total tonsillectomy using the same technique, which may introduce confounding. Studies also differed in the amount of tonsillar tissue removed in partial tonsillectomies. Few studies reported the same outcomes or used the same metrics to report outcomes such as return to normal diet.

Future Research

Future research to standardize “partial” tonsillectomy is important to promote comparability of findings. Greater standardization in techniques and outcome measures would also help to clarify comparative effectiveness. Similarly, measures that reflect outcomes of importance to children and caregivers would aid families and clinicians in shared decision making about approaches to tonsillectomy.

CONCLUSIONS

We found little data to support the superiority of either partial or total tonsillectomy. Partial tonsillectomy is associated with moderate advantages in return to normal diet or activity but can also be associated with tonsillar regrowth and recurrence of symptoms. The evidence base is limited by heterogeneity of surgical techniques that preclude quantitative analyses as well as by differences in the operationalizing of “partial” tonsillectomy.

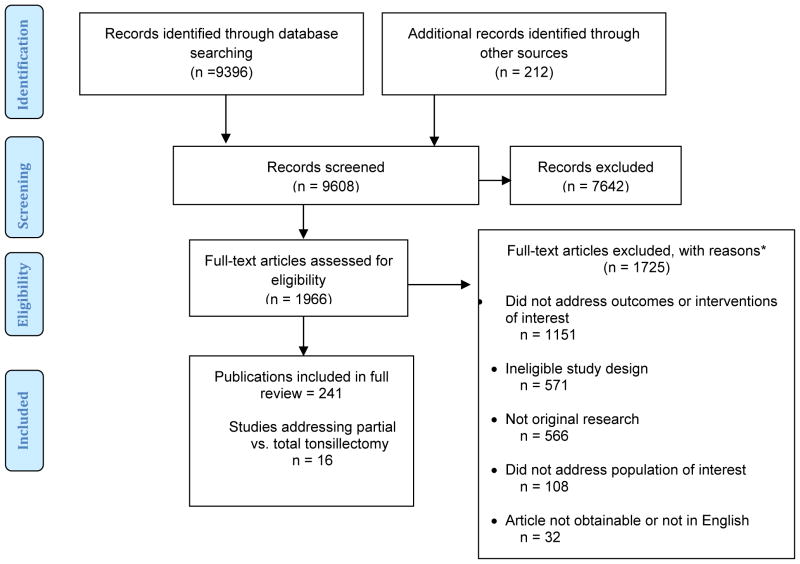

Figure 1. Disposition of studies identified for this review.

*Numbers do not tally as studies could be excluded for multiple reasons.

Abbreviations: n = Number.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This project was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (contract number: HHSA290201500003I). Salary support for D.O.F. came from grants K23DC013559 and L30DC012687 from the National Institute for Deafness and Communication Disorders of the National Institute of Health.

Dr. Shanthi Krishnaswami, Ms. Jessica Kimber, and Ms. Katherine Worley contributed to the data extraction. We gratefully acknowledge the input of the full research team and of our AHRQ Task Order Officers and Associate Editor.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The authors of this report are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Source of the work: This manuscript was derived from a systematic review conducted by the Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center (Tonsillectomy for Obstructive Sleep-Disordered Breathing or Recurrent Throat Infection in Children), which will be published in full on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality web site.

Disclosure: All authors received funding for this project under Contract No. HHSA HHSA290201500003I from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Salary support for D.O.F. came from grants K23DC013559 and L30DC012687 from the National Institute for Deafness and Communication Disorders of the National Institute of Health. No authors have any other financial or other disclosures relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Boss EF, Marsteller JA, Simon AE. Outpatient tonsillectomy in children: demographic and geographic variation in the United States, 2006. J Pediatr. 2012;160:814–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker NP, Walner DL. Trends in the indications for pediatric tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75:282–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel HH, Straight CE, Lehman EB, et al. Indications for tonsillectomy: a 10 year retrospective review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78:2151–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koltai PJ, Solares CA, Mascha EJ, et al. Intracapsular partial tonsillectomy for tonsillar hypertrophy in children. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:17–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.5541121407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walton J, Ebner Y, Stewart MG, et al. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials comparing intracapsular tonsillectomy with total tonsillectomy in a pediatric population. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138:243–9. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2012.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acevedo JL, Shah RK, Brietzke SE. Systematic review of complications of tonsillotomy versus tonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:871–9. doi: 10.1177/0194599812439017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood JM, Cho M, Carney AS. Role of subtotal tonsillectomy (‘tonsillotomy’) in children with sleep disordered breathing. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;128(Suppl 1):S3–7. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113003058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alsawaf MM, Garlapo DA. Influence of tooth contact on the path of condylar movements. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry. 1992;67:394–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(92)90256-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odhagen E, Sunnergren O, Hemlin C, et al. Risk of reoperation after tonsillotomy versus tonsillectomy: a population-based cohort study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edmonson MB, Eickhoff JC, Zhang C. A population-based study of acute care revisits following tonsillectomy. J Pediatr. 2015;166:607–12. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zagolski O. Why do palatine tonsils grow back after partial tonsillectomy in children? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:1613–7. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francis DO, Chinnadurai S, Sathe NA, Morad A, Jordan AK, Krishnaswami S, Fonnesbeck C, McPheeters ML, et al. Tonsillectomy for Obstructive Sleep-Disordered Breathing or Recurrent Throat Infection in Children. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; (Prepared by the Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290201500003I.) AHRQ Publication. in press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francis D, Fonnesbeck C, Sathe NA, et al. Postoperative Bleeding and Associated Utilization Following Tonsillectomy in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. doi: 10.1177/0194599816683915. submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viswanathan M, Ansari MT, Berkman ND, et al. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville (MD): 2008. Assessing the Risk of Bias of Individual Studies in Systematic Reviews of Health Care Interventions. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Ansari MT, et al. Grading the strength of a body of evidence when assessing health care interventions: an EPC update. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabr S, Harhash K, Fouly M, et al. Microdebrider intracapsular tonsillotomy versus conventional extracapsular tonsillectomy. The Egyptian Journal of Otolaryngology. 2014;30:220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaidas KS, Kaditis AG, Papadakis CE, et al. Tonsilloplasty versus tonsillectomy in children with sleep-disordered breathing: short- and long-term outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1294–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.23860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pruegsanusak K, Wongsuwan K, Wongkittithawon J. A randomized controlled trial for perioperative morbidity in microdebrider versus cold instrument dissection tonsillectomy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93:558–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korkmaz O, Bektas D, Cobanoglu B, et al. Partial tonsillectomy with scalpel in children with obstructive tonsillar hypertrophy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72:1007–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang KW. Intracapsular versus subcapsular coblation tonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:153–57. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skoulakis CE, Papadakis CE, Manios AG, et al. Tonsilloplasty in children with obstructive symptoms. J Otolaryngol. 2007;36:240–6. doi: 10.2310/7070.2007.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park A, Proctor MD, Alder S, et al. Subtotal bipolar tonsillectomy does not decrease postoperative pain compared to total monopolar tonsillectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:1205–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang KW. Randomized controlled trial of Coblation versus electrocautery tonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lister M. Microdebrider partial tonsillectomy vs. electrosurgical tonsillectomy: a randomized, double-blind, paired-control study of postoperative pain. 20th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology (ASPO); 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ericsson E, Graf J, Lundeborg-Hammarstrom I, et al. Tonsillotomy versus tonsillectomy on young children: 2 year post surgery follow-up. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;43:26. doi: 10.1186/s40463-014-0026-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ericsson E, Lundeborg I, Hultcrantz E. Child behavior and quality of life before and after tonsillotomy versus tonsillectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1254–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan KH, Friedman NR, Allen GC, et al. Randomized, controlled, multisite study of intracapsular tonsillectomy using low-temperature plasma excision. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:1303–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.11.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ericsson E, Graf J, Hultcrantz E. Pediatric tonsillotomy with radiofrequency technique: long-term follow-up. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1851–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000234941.95636.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ericsson E, Wadsby M, Hultcrantz E. Pre-surgical child behavior ratings and pain management after two different techniques of tonsil surgery. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:1749–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hultcrantz E, Ericsson E. Pediatric tonsillotomy with the radiofrequency technique: less morbidity and pain. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:871–7. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200405000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derkay CS, Darrow DH, Welch C, et al. Post-tonsillectomy morbidity and quality of life in pediatric patients with obstructive tonsils and adenoid: microdebrider vs electrocautery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:114–20. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beriat GK, Ezerarslan H, Kocaturk S. Microdebrider tonsillotomy in children with obstructive tonsillar hypertrophy. Journal of Clinical and Analytical Medicine. 2013:4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coticchia JM, Yun RD, Nelson L, et al. Temperature-controlled radiofrequency treatment of tonsillar hypertrophy for reduction of upper airway obstruction in pediatric patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:425–30. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobol SE, Wetmore RF, Marsh RR, et al. Postoperative recovery after microdebrider intracapsular or monopolar electrocautery tonsillectomy: a prospective, randomized, single-blinded study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:270–4. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H, Fu Y, Feng Y, et al. Tonsillectomy versus tonsillotomy for sleep-disordered breathing in children: a meta analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]