Abstract

The present study evaluated the latent structure of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO FFI) and relations between the five-factor model (FFM) of personality and dimensions of DSM-IV anxiety and depressive disorders (panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder [GAD], obsessive–compulsive disorder, social phobia [SOC], major depressive disorder [MDD]) in a large sample of outpatients (N = 1,980). Exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) was used to show that a five-factor solution provided acceptable model fit, albeit with some poorly functioning items. Neuroticism demonstrated significant positive associations with all but one of the disorder constructs whereas Extraversion was inversely related to SOC and MDD. Conscientiousness was inversely related to MDD but demonstrated a positive relationship with GAD. Results are discussed in regard to potential revisions to the NEO FFI, the evaluation of other NEO instruments using ESEM, and clinical implications of structural paths between FFM domains and specific emotional disorders.

Keywords: NEO Five-Factor Inventory, five-factor model, latent structure, anxiety, depression, clinical sample, exploratory structural equation modeling

Introduction

Cattell (1946) first argued that personality structure should be studied by factor analyzing self-report ratings of descriptive adjectives and statements. Using this approach, a five-factor model (FFM) of personality has evolved over the past several decades (see Costa & Widiger, 2002). Currently, the FFM may be the most widely used personality theory within psychology. For example, social, personality, and industrial/organizational psychologists have used the FFM to examine individual differences in a variety of outcomes and processes, including attachment (Noftle & Shaver, 2006), career success (Seibert & Kraimer, 2001), and performance motivation (Judge & Ilies, 2002). Within clinical psychology, the FFM has received increased attention among psychopathology researchers. Specifically, a significant amount of research has focused on the relationship between the FFM and the personality disorders defined by the fourth edition–text revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000; for a review, see Samuel & Widiger, 2008), including the potential utility of the FFM as a dimensional classification system to complement or replace Axis II (e.g., Rottman, Ahn, Sanislow, & Kim, 2009; Samuel & Widiger, 2006; Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009).

Psychometric Properties of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory

Costa and McCrae’s (1989, 1992) NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI), Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R), and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO FFI) were developed with the aim of assessing the five domains of the FFM: (a) neuroticism (N), the tendency to experience negative emotions and psychological distress in response to stressors; (b) extraversion (E), the degree of sociability, positive emotionality, and general activity; (c) openness to experience (O), levels of curiosity, independent judgment, and conservativeness; (d) agreeableness (A), altruistic, sympathetic, and cooperative tendencies; and (e) conscientiousness (C), one’s level of self-control in planning and organization. The five domains are hypothesized to be relatively orthogonal to one another. The NEO inventories are composed of descriptive statements (e.g., “I am not a worrier,” “I really enjoy talking to people”) rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The NEO PI and PI-R consist of 180 and 240 items, respectively, and may be used to compute five domain (i.e., N, E, O, A, and C) and 30 facet (six subfactors for each of the five domains) scores. In contrast, the NEO FFI contains 60 items and may be used to derive only the five domain scores (12 items per domain). NEO FFI items were selected from the NEO PI items that demonstrated the strongest correlations with their respective domain factor score, regardless of the item’s intended facet (i.e., the 30 NEO PI facets are not equally represented by NEO FFI items). Each of the five domains of the NEO FFI has been found to possess adequate internal consistency and temporal stability (α = .68 to .86, Costa & McCrae, 1992; r = .86 to .90, Robins, Fraley, Roberts, & Trzesniewski, 2001).

Despite favorable reliability estimates, principal component analysis (PCA), exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) examinations of the NEO FFI have produced mixed findings. For instance, Egan, Deary, and Austin (2000) evaluated the NEO FFI in a large nonclinical sample using PCA and EFA with varimax and oblique rotations. Although the anticipated five-factor structure was generally supported (i.e., the majority of items loaded adequately onto their expected factor), a handful of items were found to have (a) salient cross-loadings (e.g., items with loadings ≥ .30 on more than one factor), and/or (b) nonsalient primary factor loadings (e.g., items with no loadings ≥ .30). Such findings are consistent with prior PCA and EFA examinations of the NEO FFI in nonclinical samples (e.g., Holden & Fekken, 1994; Parker & Stumpf, 1998) and have served as a catalyst for studies attempting to resolve these undesirable results. For instance, McCrae and Costa (2004) responded to Egan et al. (2000) by evaluating each NEO FFI item and replacing those that consistently performed poorly in PCA and EFA. Weak items were identified by quantifying the extent of empirical support for each item with a thorough literature review (e.g., calculating how many studies found certain items to have loadings < .30). In total, 14 items were identified and replaced with other items from their respective NEO PI-R domain. Unfortunately, these revisions resulted in only trivial psychometric improvements, leading the authors to conclude that published version of NEO FFI was sufficient.

Fewer studies have evaluated the NEO FFI with CFA. Although Egan et al. (2000) conducted a CFA to replicate the solution obtained with PCA/EFA, they did not report goodness-of-fit statistics. Studies that have considered CFA model fit have failed to support the conjectured latent structure of the NEO FFI. For instance, Schmitz, Hartkamp, Baldini, Rollnik, and Tress’s (2001) CFA of the NEO FFI in a sample of German outpatients with psychosomatic complaints found that two-, four-, and five-factor models failed to result in adequate fit (e.g., goodness-of-fit index = .82 to .84, root mean square residual = .12 to .16). Moreover, CFA interfactor correlations failed to support hypotheses about the orthogonal nature of the NEO domains (e.g., N and E r = −.46). Marsh et al. (in press) recently obtained similar results using CFA in a large nonclinical sample (i.e., poor model fit, high interfactor correlations). Although CFA examinations of the NEO FFI are limited to a few studies, these findings are consistent with results obtained in CFA studies of the NEO PI and NEO PI-R (e.g., nonsignificant factor loadings and poor goodness-of-fit statistics; Church & Burke, 1994; Parker, Bagby, & Summerfeldt, 1993).

In addition to criticisms about the lack of psychometric support for the NEO FFI (e.g., Egan et al., 2000; Parker & Stumpf, 1998; Schmitz et al., 2001), such findings have led researchers to question the adequacy of CFA in the study of personality structure (see Aluja, Garcia, Garcia, & Seisdedos, 2005; Church & Burke, 1994; McCrae, Zonderman, Costa, Bond, & Paunonen, 1996; Parker et al., 1993; Vassend & Skrondal, 1997). For instance, McCrae et al. (1996) argued that “there is no theoretical reason why traits should not have meaningful loadings on three, four, or five factors” (p. 553). Likewise, others have hypothesized that the congeneric model used in CFA (i.e., specification of each indicator to load onto a single latent factor) is overly restrictive, as personality indicators are prone to have salient secondary loadings unless factors are defined by only a small number of nearly synonymous items (Church & Burke, 1994). Marsh et al. (2009) also discuss how CFA models that fix cross-loadings to zero may inflate NEO interfactor correlations to appear nonorthogonal.

Much of this discussion reflects a fundamental difference in how CFA and EFA attempt to obtain simple structure (i.e., the most interpretable solution). In EFA with two or more factors, factor rotation is needed to obtain simple structure because the factor-loading matrix is fully saturated (i.e., all indicators are freely estimated). Conversely, factor rotation is unnecessary in CFA because simple structure is obtained by fixing most (if not all) item–factor cross-loadings to zero. Accordingly, the increased parsimony of CFA models (i.e., model overidentification) allows for model specifications not possible in the EFA framework (e.g., freely estimating indicator error covariances). Along these lines, a good-fitting measurement model is needed prior to examining structural (i.e., regressive) paths between latent variables, thus making CFA an important prelude to structural equation modeling. Exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) is a recently developed methodology that combines the techniques of EFA and CFA (see Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009). ESEM is unique in that it may be used to simultaneously examine EFA and CFA measurement models and generate parameters estimates according to either framework. For example, ESEM may be used to freely estimate the relationships between all observed and latent variables, implement orthogonal and oblique factor rotations, specify correlated errors, calculate standard errors and goodness-of-fit statistics, and regress endogenous latent variables on exogenous latent variables.

The advancement of ESEM has allowed researchers to examine the properties of the NEO FFI in novel ways. Marsh et al. (in press) was the first study to use ESEM to evaluate the NEO FFI. The data were modeled with and without a priori specification of 57 correlated errors corresponding to NEO FFI item pairs derived from the same NEO PI facets (e.g., correlated error was specified between Items 1 and 21 because both load on the Anxiety facet of the N domain of the NEO PI). Although ESEM without correlated errors provided better model fit than CFA, fit statistics were still generally below prevailing standards of acceptable fit (e.g., Tucker–Lewis index [TLI] = .82; comparative fit index [CFI] = .85). In contrast, ESEM with correlated errors resulted in marginally acceptable fit (TLI = .89; CFI = .91; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .03), by far the most promising model fit ever obtained for the NEO FFI. ESEM also resulted in weaker interfactor correlations than CFA, which is more consistent with FFM theory (i.e., the five domains are hypothesized to be orthogonal). Although the goodness-of-fit statistics obtained from the ESEM models were modest relative to proposed “cutoffs” (e.g., TLI and CFI near or greater than .95; Hu & Bentler, 1999), others have contended that these guidelines may be overly restrictive (e.g., Beauducel & Whittmann, 2005; Marsh, Hau, & Grayson, 2005; Marsh, Hau, & Wen, 2004). In particular, Marsh et al. (2005) recommend that psychometric evaluations of longer questionnaires (e.g., 50 or more items, five or more factors) should not use model fit guidelines with excessive strictness. Moreover, Marsh et al. (in press) conclude that traditional CFA models are not appropriate for the NEO FFI and that ESEM should be used in its place to utilize the benefits of confirmatory models (e.g., adjustment for measurement error).

Although the findings of Marsh et al.’s (in press) ESEM support the factor structure of the NEO FFI in normative samples, no study has yet used ESEM to evaluate the latent structure of the NEO FFI in a clinical sample. Latent structural replications in clinical samples are necessary because personality self-reports may be influenced by the experience of clinical disorders (e.g., Costa, Bagby, Herbst, & McCrae, 2005) and thereby affect a scale’s psychometric properties. Moreover, validation of the NEO FFI structure in a clinical sample is particularly important given the increased attention the FFM of personality has received from psychopathology researchers (e.g., Bienvenu et al., 2001, 2004; Rottman et al., 2009; Samuel & Widiger, 2006; Tackett, Quilty, Sellbom, Rector, & Bagby, 2008). If the latent structure of the NEO FFI is supported in clinical samples using ESEM, this bolsters its use in studies of personality and psychopathology.

The Five-Factor Model and Anxiety and Depressive Disorders

Although personality disorder researchers have given increased attention to the FFM (e.g., Costa & Widiger, 2002; Rottman et al., 2009; Samuel & Widiger, 2006), there has been less focus on the relations between the FFM and the anxiety and mood disorders. Instead, theory and research examining personality/temperament within the emotional disorders has tended to underscore two-factor models comprising N and E or closely related constructs (e.g., negative/positive affect, behavioral inhibition/activation; Barlow, 2002). Research examining such models has provided robust support for increased levels of N across the anxiety and mood disorders and decreased levels of E within depression, social anxiety (SOC), and possibly agoraphobia (Bienvenu et al., 2001, 2004; Brown, 2007; Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1998; Carrera et al., 2006; Rosellini, Lawrence, Meyer, & Brown, 2010; Trull & Sher, 1994; Watson, Clark, & Carey, 1988).

Examinations of the anxiety and mood disorders and the other three domains of the FFM (O, A, and C) have occurred less frequently. Using the NEO FFI and DSM-III-R (APA, 1987) criteria, Trull and Sher (1994) found that high O and low C predicted a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). However, other examinations of the FFM and MDD using the NEO PI-R have failed to fully replicate these findings, obtaining support for this pattern only at the facet level of O and C (Bienvenu et al., 2001, 2004). Whereas low C may also be salient to generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), high O has also been linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; Bienvenu et al., 2004), but with limited support (e.g., Wu, Clark, & Watson, 2006). More recently, Tackett et al. (2008) used the NEO PI-R to compare mean factor scores for individuals diagnosed with various anxiety and mood disorders. Compared with individuals with MDD, participants with GAD tended to display lower levels of A, whereas those with OCD exhibited greater E. Panic disorder was associated with greater C than was agoraphobia.

Although the extant literature has been useful in clarifying associations between the five domains of the FFM and specific anxiety and mood disorders, it has been limited in several ways. For instance, nearly all prior research has focused on the relationship between the FFM and diagnostic group membership over one’s lifetime using DSM-III-R criteria (Bienvenu et al., 2001, 2004; Trull & Sher, 1994). Findings obtained in these samples may not generalize to samples with current clinical disorders using DSM-IV criteria. Research examining the FFM concurrently with psychopathology has been limited to tests of group differences based on diagnosis (Tackett et al., 2008). Unfortunately, dichotomous representations of clinical status increase measurement error and fail to capture important information such as individual differences in symptom severity and comorbidity (Brown & Barlow, 2005, 2009). More generally, the lack of CFA support for the NEO FFI has precluded an examination of the relations between NEO domains and psychopathology while adjusting for measurement error. To date, no studies have examined relations between the FFM and dimensions of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large clinical sample.

Present Study

The current study evaluated the latent structure of the NEO FFI and its relationships with dimensions of DSM anxiety and depressive disorders in a large sample of outpatients. It was hypothesized that ESEM would support the five-factor structure of the NEO FFI (albeit with some poor functioning items) and provide acceptable model fit, comparable with the solutions obtained by Marsh et al. (in press). Correlations between the five factors were also expected to be similar to Marsh et al (i.e., in the low-to-modest range). A number of significant structural paths were also predicted to be found between dimensions of the FFM and the DSM anxiety and depressive disorders. Whereas a significant positive path was hypothesized between N and all disorders examined, low E was anticipated to have a significant inverse relationship with SOC, MDD, and possibly panic disorder/agoraphobia. O was hypothesized to be positively associated with MDD and C was expected to be inversely related to MDD and GAD. No significant paths were anticipated between A and the DSM disorder factors.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 1,980 participants who presented for assessment and treatment at the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University. The sample was predominantly female (60%), Caucasian (89%), and of non-Hispanic (97%) ethnicity, with smaller percentages identifying as African American (3%) and Asian (4%). The average age of the sample was 33.09 years (SD = 11.85, range = 18 to 89). Individuals were assessed by doctoral students or doctoral-level clinical psychologists using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV–Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L; Di Nardo, Brown, & Barlow 1994). The ADIS-IV-L is a semistructured interview that assesses DSM-IV (APA, 2000) anxiety, mood, somatoform, and substance-use disorders. The ADIS-IV-L also includes prompts that screen for the presence of other disorders (e.g., symptoms of psychosis). When administering the ADIS-IV-L, clinicians assign each diagnosis a 0 to 8 clinical severity rating (CSR) that represents the degree of distress or impairment in functioning associated with specific diagnoses. Diagnoses with a CSR of 4 (definitely disturbing/disabling) or higher are considered to be at a clinical level (i.e., meeting the DSM diagnostic threshold). The ADIS-IV-L has shown good-to-excellent reliability for the majority of anxiety and mood disorders (Brown, Di Nardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001). Rates of the most common clinical disorders at intake were as follows: social phobia (47%), mood disorders (i.e., major depression, dysthymic disorder, depressive disorder not otherwise specified; 39%), generalized anxiety disorder (29%), panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (25%), specific phobia (16%), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (15%). Study exclusionary criteria were current suicidal/homicidal intent and/or plan, psychotic symptoms, or significant cognitive impairment (e.g., diagnosis of dementia, mental retardation).

Measures

As previously mentioned, the NEO FFI (Costa & McCrae, 1992) is a 60-item self-report instrument used to measure the five personality domains according to the FFM: N, E, O, A, and C (12 items per domain). The NEO FFI includes self-descriptive statements that participants respond to using a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) Likert-type scale. Scores for each domain are calculated by summing the 12 item responses. A total of 28 NEO FFI items are reverse-worded.

Indicators of Latent DSM Anxiety and Depressive Disorder Dimensions

During the clinical interview, diagnosticians made dimensional ratings on various 0 to 8 scales for key disorder features assessed by the ADIS-IV-L. These ratings were obtained regardless of presenting difficulties or if the disorder was actually assigned at a clinical level. Following ADIS-IV-L administration, diagnosticians made additional ratings on a 0 (absent) to 8 (very severely disturbing/disabling) scale for specific DSM criteria of various anxiety and depressive disorders.

Panic Disorder/Agoraphobia (PD/AG)

Three indicators were used to form a latent variable representing PD/AG: (a) a sum composite of 22 situational avoidance ratings made within the AG section of the ADIS-IV-L, (b) a clinical rating for DSM-IV Criterion A1 of PD/AG (recurrent and unexpected panic attacks), and (c) a composite rating for the three features comprising the DSM-IV A2 criterion of PD (worry about future panic, worry about the implications of panic, and a change in behavior due to panic).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

Three indicators were used for the GAD factor: (a) a composite rating for excessiveness of worry in eight areas (e.g., work/school, family, finances) made within the GAD section of the ADIS-IV-L, (b) a single rating representing GAD Criterion B (uncontrollability of worry), and (c) a composite severity rating of the six associated symptoms of GAD (e.g., restlessness, irritability).

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Two composite ratings from the OCD section of the ADIS-IV-L comprised the OCD latent variable: (a) frequency/distress associated with nine common obsessions (e.g., intrusive aggressive thoughts, contamination) and (b) frequency of six common compulsions (e.g., checking, ordering/arranging).

Social Anxiety Disorder (SOC)

The SOC latent variable was defined by two indicators: (a) a composite of ratings of fear of 13 social situations (e.g., initiating/maintaining conversations, going to parties) and (b) a composite rating of social phobia Criterion B (invariably experiencing anxiety), C (avoidance or endurance of anxiety), and D (interference/distress).

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

Two indicators were used to represent the latent construct of MDD: (a) a composite rating of the two key features of MDD (depression and anhedonia) and (2) a composite rating of the seven associated features of MDD (e.g., psychomotor agitation/slowness, insomnia/hypersomnia)

Data Analyses

The raw data were analyzed with latent variable software using direct maximum likelihood minimization functions (Mplus 5.2, Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2009).1 ESEM model fit was examined using the TLI, CFI, RMSEA and its test of close fit (CFit), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Multiple goodness-of-fit indices were evaluated to examine various aspects of model fit (i.e., absolute fit, parsimonious fit, fit relative to the null model; cf. Brown, 2006). Although guidelines for acceptable fit have been defined (e.g., RMSEA near or less than .06, CFit greater than .05, TLI and CFI near or greater than .95, SRMR near or below .08; Hu & Bentler, 1999), researchers have recently cautioned the application of such recommendations in psychometric evaluations of measures comprising 50 or more items loading onto five or more factors (e.g., Marsh et al., 2005). Unstandardized and completely standardized solutions were examined to evaluate the significance and strength of parameter estimates. Standardized residuals and modification indices were used to determine the presence of any localized areas of strain in the solutions.

Results

Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling

The sample was subdivided to evaluate and cross-validate the latent structure of the NEO FFI. The 60 NEO FFI items were analyzed in Sample 1 (n = 990) using geomin rotation. Using the rationale of Marsh et al. (in press), ESEM was used to specify correlated residuals (which cannot be done in EFA) between items originating from the same NEO PI facet (57 in total). In others words, items from the same facet were expected to share variance in addition to that explained by the five factors. The five-factor ESEM solution provided marginally acceptable fit, χ2(1423) = 3185.01, p < .001, SRMR = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.05 (CFit p = 1.00), TLI = 0.89, CFI = .91.2 Although this model indicated some localized areas of strain (e.g., modification indices [MIs] suggesting salient error covariances), none appeared to be substantively justified (e.g., largest MI = 45.47 between Item 10, “I’m pretty good about pacing myself so as to get things done on time,” and Item 55, “I never seem to be able to get organized”). Thus, the model was not re-specified with additional correlated residuals. ESEM with geomin rotation was then applied to Sample 2 (n = 990) to replicate the solution obtained in Sample 1. Again, the model provided marginally acceptable fit, χ2(1423) = 3266.46, p < .001, SRMR = .03, RMSEA = .04 (CFit p = 1.00), TLI = .88, CFI = .90, with no interpretable areas of strain.3 Table 1 shows the interfactor correlations obtained with ESEM in each sample. Consistent with study hypotheses, all correlations were in the low-to-modest range (rs = .00 to −.32).

Table 1.

Zero-Order Correlations Between Factors of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory in Sample 1 (Above the Diagonal; N = 990) and Sample 2 (Below the Diagonal; N = 990) Using Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling

| Latent Factor | N | E | O | A | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | — | −.27 | .06 | −.09 | −.27 |

| E | −.25 | — | .12 | .08 | .20 |

| O | .09 | .12 | — | .00 | −.05 |

| A | −.26 | .12 | .04 | — | .08 |

| C | −.32 | .25 | −.04 | .13 | — |

Note. N = Neuroticism, E = Extraversion, O = Openness, A = Agreeableness, and C = Conscientiousness. Exploratory structural equation modeling was conducted with maximum likelihood estimation and geomin rotation.

Table 2 presents the factor loadings obtained in the ESEMs. In all, 47 of the 60 items had salient loadings on a single factor in both samples. However, 13 NEO FFI items had salient cross-loadings and/or nonsalient factor loadings in one or both of the samples. In both samples, Items 3, 33, and 38 did not have any salient loadings whereas Item 52 had cross-loadings. Other items had nonsalient loadings in only one of the samples (Items 18, 28, and 49). Although Items 8 and 34 had salient primary loadings in both analyses, they loaded on an unexpected factor (e.g., Item 8 is intended to be an indicator of O but loaded on C; Item 34 is intended to be an indicator of A but loaded on E).

Table 2.

Exploratory Structural Equation Models of a Five-Factor Solution for the 60-item NEO Five-Factor Inventory in Samples 1 (N = 990) and 2 (N = 990)

| Item | Factor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| N | E | O | A | C | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | |

| N1 | .36 | .37 | −.01 | −.03 | −.03 | −.06 | .10 | .02 | .15 | .10 |

| N6 | .60 | .61 | −.13 | −.17 | −.03 | −.01 | .11 | .07 | −.01 | −.01 |

| N11 | .63 | .68 | .08 | .08 | −.01 | −.02 | .01 | .04 | −.01 | .04 |

| N16 | .50 | .46 | −.12 | −.14 | .05 | .03 | .05 | −.02 | −.08 | −.06 |

| N21 | .52 | .56 | −.03 | −.02 | −.01 | .00 | −.04 | −.11 | .12 | .12 |

| N26 | .65 | .64 | −.10 | −.12 | .00 | .02 | .01 | .00 | −.15 | −.12 |

| N31 | .43 | .39 | .02 | −.04 | .01 | .04 | .09 | −.08 | .04 | .00 |

| N36 | .52 | .49 | .00 | .01 | −.07 | −.03 | −.25 | −.26 | .02 | .08 |

| N41 | .59 | .67 | −.03 | −.03 | −.05 | −.10 | .03 | .04 | −.26 | −.16 |

| N46 | .52 | .48 | −.15 | −.15 | .09 | .03 | .05 | −.01 | −.10 | −.09 |

| N51 | .56 | .58 | .05 | .02 | −.06 | −.13 | −.03 | −.01 | −.26 | −.23 |

| N56 | .55 | .51 | −.10 | −.10 | .10 | .16 | −.03 | −.02 | −.14 | −.10 |

| E2 | .02 | .05 | .69 | .67 | −.08 | −.11 | −.07 | .03 | −.07 | −.05 |

| E7 | −.14 | −.14 | .37 | .36 | .16 | .11 | .07 | .17 | .02 | −.04 |

| E12 | −.27 | −.31 | .32 | .22 | −.01 | −.04 | .11 | .16 | −.14 | −.11 |

| E17 | .00 | .00 | .72 | .65 | .06 | .03 | .05 | .15 | −.03 | .03 |

| E22 | .02 | −.03 | .61 | .59 | −.02 | .05 | −.25 | −.14 | −.04 | −.03 |

| E27 | −.15 | −.03 | .50 | .43 | −.03 | −.19 | .12 | .21 | −.15 | −.04 |

| E32 | −.05 | −.02 | .30 | .38 | .14 | .13 | −.20 | −.09 | .12 | .12 |

| E37 | −.25 | −.19 | .56 | .53 | .02 | .01 | .07 | .17 | .09 | .05 |

| E42 | −.37 | −.39 | .38 | .29 | .02 | .02 | .10 | .15 | .05 | .03 |

| E47 | .00 | .04 | .40 | .47 | .00 | .03 | −.23 | −.15 | .31 | .24 |

| E52 | −.12 | −.07 | .40 | .45 | .02 | .00 | −.10 | −.03 | .34 | .35 |

| E57 | −.18 | −.19 | .44 | .37 | −.03 | −.06 | −.09 | −.05 | .04 | .03 |

| O3 | −.05 | −.02 | −.06 | −.12 | .25 | .14 | .14 | .02 | −.21 | −.25 |

| O8 | −.13 | −.04 | −.07 | −.08 | .10 | .06 | −.06 | .06 | −.30 | −.32 |

| O13 | .01 | .01 | −.06 | −.05 | .62 | .59 | .00 | .00 | .01 | −.03 |

| O18 | −.05 | −.07 | −.01 | −.03 | .30 | .29 | .11 | .12 | .05 | .04 |

| O23 | .02 | .05 | .08 | −.03 | .42 | .37 | .09 | .18 | −.06 | −.02 |

| O28 | −.05 | −.20 | .12 | .15 | .32 | .29 | .01 | .08 | −.06 | −.10 |

| O33 | .07 | .03 | .07 | .00 | .24 | .27 | .15 | .05 | .08 | .09 |

| O38 | −.09 | −.04 | −.17 | −.17 | .22 | .15 | −.03 | −.02 | −.05 | −.02 |

| O43 | .10 | .09 | .04 | .04 | .56 | .55 | .06 | .10 | .00 | .01 |

| O48 | −.01 | .00 | −.01 | −.03 | .59 | .54 | .08 | .15 | −.02 | −.06 |

| O53 | −.03 | −.01 | .03 | .13 | .61 | .60 | −.09 | −.03 | .14 | .13 |

| O58 | .01 | −.04 | −.09 | −.02 | .70 | .65 | −.12 | −.07 | −.01 | −.08 |

| A4 | .19 | .07 | .24 | .13 | .05 | .09 | .33 | .31 | .12 | .11 |

| A9 | .23 | −.21 | −.06 | −.14 | .02 | .10 | .42 | .38 | .05 | .08 |

| A14 | −.08 | −.03 | .02 | .01 | −.09 | −.12 | .50 | .48 | .14 | .15 |

| A19 | −.21 | −.24 | −.03 | −.05 | .02 | −.07 | −.41 | −.38 | .05 | .03 |

| A24 | −.36 | −.26 | .19 | .13 | .00 | −.05 | .39 | .47 | −.05 | −.01 |

| A29 | −.38 | −.29 | .10 | −.03 | .08 | .08 | .38 | .36 | −.09 | −.02 |

| A34 | −.15 | −.12 | .36 | .39 | −.06 | −.01 | .14 | .27 | .11 | .04 |

| A39 | .01 | −.02 | .24 | .14 | −.03 | −.08 | .50 | .57 | .01 | .00 |

| A44 | −.09 | −.07 | −.03 | −.11 | −.01 | .02 | .47 | .45 | −.14 | −.08 |

| A49 | .20 | .16 | .20 | .09 | .12 | .17 | .29 | .39 | .23 | .18 |

| A54 | .10 | .03 | −.01 | −.15 | .01 | .00 | .43 | .46 | .00 | −.02 |

| A59 | .00 | −.01 | −.11 | −.20 | −.05 | −.02 | .60 | .51 | .13 | .17 |

| C5 | .04 | .01 | .01 | .02 | −.13 | −.07 | .02 | .00 | .43 | .47 |

| C10 | −.19 | −.12 | −.09 | −.09 | −.06 | −.14 | .01 | .07 | .58 | .59 |

| C15 | −.06 | −.01 | −.13 | −.10 | .06 | .10 | −.04 | −.14 | .37 | .45 |

| C20 | .13 | .17 | −.00 | .03 | .08 | .08 | .18 | .20 | .56 | .56 |

| C25 | −.14 | −.17 | .11 | .03 | .00 | .05 | −.10 | −.13 | .62 | .62 |

| C30 | −.25 | −.30 | −.10 | −.14 | −.13 | −.10 | .13 | .05 | .46 | .47 |

| C35 | .07 | .00 | .16 | .16 | .07 | .15 | −.01 | −.01 | .72 | .61 |

| C40 | −.04 | −.01 | .00 | .03 | −.02 | −.01 | .11 | .14 | .60 | .60 |

| C45 | −.18 | −.16 | −.05 | −.06 | −.17 | −.09 | .15 | .12 | .55 | .52 |

| C50 | −.08 | −.03 | .06 | .12 | −.01 | −.05 | −.03 | −.05 | .78 | .78 |

| C55 | −.23 | −.19 | −.09 | −.10 | −.07 | −.08 | .05 | .03 | .50 | .54 |

| C60 | .14 | .14 | .19 | .17 | .12 | .18 | −.05 | .02 | .54 | .52 |

Note. N = Neuroticism, E = Extraversion, O = Openness, A = Agreeableness, C = Conscientiousness, S1 = Sample 1, S2 = Sample 2. Factor loadings ≥ |.30| are in boldface. Italicized items were identified as poorly functioning by McCrae and Costa (2004). Exploratory structural equation modeling was conducted with maximum likelihood estimation and geomin rotation.

Structural Relations Between NEO FFI and DSM-IV Disorder Factors

Using a subset of Sample 1 for which dimensional ratings of DSM-IV features were available (n = 611), a measurement model composed of five DSM-IV disorder constructs (PD/AG, GAD, OCD, SOC, and MDD) was evaluated. Two areas of strain were found between (a) indicators representing excessive worry and uncontrollably worry (MI = 28.52) and (b) indicators representing the associated symptoms of GAD and MDD (MI = 50.56). These areas of strain were viewed as consistent with arguments that the excessiveness and uncontrollability criteria of GAD may be highly overlapping (e.g., Andrews et al., 2010) and research demonstrating the strong phenotypic overlap between GAD and depression (e.g., high comorbidity between GAD and depression when ignoring the DSM hierarchy rule; Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham, & Mancill, 2001). Thus, the measurement model was re-specified to allow these residuals to freely covary. The revised measurement model provided acceptable fit, χ2(44) = 95.25, p < .001, SRMR = .03, RMSEA = .05 (CFit p = .63), TLI = .98, CFI = .99. A 10-factor measurement model composed of the five NEO FFI factors (modeled using ESEM) and five DSM-IV disorder constructs (modeled using CFA) was then fit to the data. The 10-factor model provided marginally acceptable fit, χ2(2160) = 3562.619, p < .001, SRMR = .04, RMSEA = .03 (CFit p = 1.00), TLI = .90, CFI = .91. There were no substantive changes in factor loadings for the NEO FFI item compared with the ESEMs conducted in Samples 1 and 2. Examination of modification indices and standardized residuals of the 10-factor model revealed no additional areas of strain in the solution.

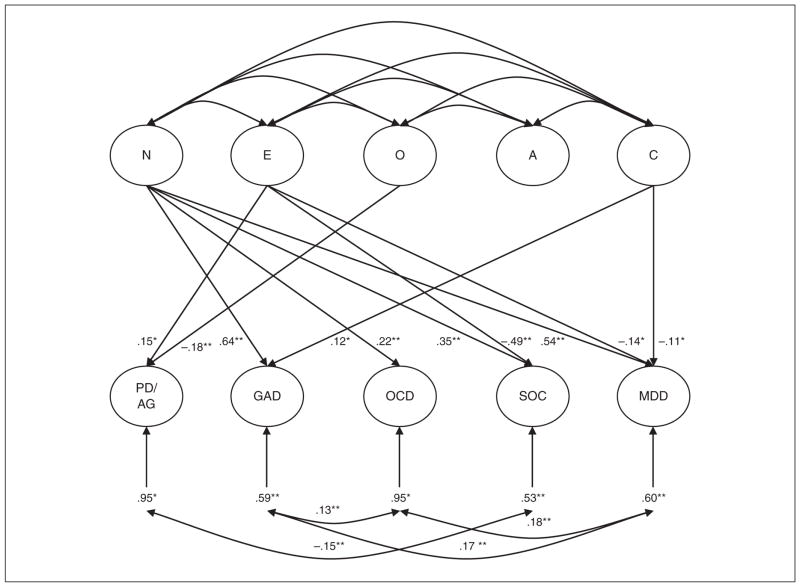

Zero-order correlations between the DSM-IV disorder constructs and the NEO FFI factors from the 10-factor measurement model are presented in Table 3. With the exception of A, all FFM domains demonstrated significant correlations with at least one DSM-IV disorder construct. Whereas N was significantly positively associated with all DSM-IV factors except PD/AG (r = −.07), E was inversely related to GAD, SOC, and MDD. C was inversely related to only SOC and MDD, whereas O was negatively associated with PD/AG and positively related to GAD. Structural relations between NEO factors and emotional disorders were evaluated by regressing the latent DSM-IV disorder dimensions onto the NEO FFI factors. Figure 1 shows all significant completely standardized paths between DSM-IV dimensions and NEO factors. The structural model generally supported study hypotheses; whereas N was found to have significant positive associations with GAD (completely standardized path, γ = .64), SOC (γ = .35), OCD (γ = .22), and MDD (γ = .54), E demonstrated a significant inverse relationship only with MDD (γ = −.14) and SOC (γ = −.49). Counter to study hypotheses, PD/AG was not predicted by N and evidenced a significant positive relationship with E (e.g., higher levels of E predicted greater severity of PD/AG; γ = .15).

Table 3.

Zero-Order Correlations Between Factors of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory and DSM-IV Disorder Dimensions

| Latent Factor | N | E | O | A | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD/AG | −.07 | .12 | −.15 | .02 | .03 |

| GAD | .62 | −.14 | .15 | −.07 | −.02 |

| SOC | .51 | −.59 | −.01 | −.05 | −.20 |

| OCD | .19 | .01 | .03 | −.07 | −.01 |

| MDD | .60 | −.33 | .06 | −.07 | −.25 |

Note. N = Neuroticism, E = Extraversion, O = Openness, A = Agreeableness, C = Conscientiousness, PD/AG = panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, GAD = generalized anxiety disorder, SOC = social phobia, OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder, MDD = major depressive disorder. Correlations are completely standardized parameter estimates based on the revised 10-factor measurement model evaluated in a subsample (N = 611) of Sample 1. All correlations ≥ |.09| are statistically significant at p < .05. DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.).

Figure 1.

Latent structural relationships between the five factors of personality and dimensions of DSM-IV disorder constructs

Note. N = Neuroticism; E = Extraversion; O = Openness; A = Agreeableness; C = Conscientiousness; PD/AG = panic disorder with or without agoraphobia; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; OCD = obsessive–compulsive disorder; SOC = social phobia; MDD = major depressive disorder; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). Only significant paths and residual correlations are shown. Completed standardized estimates are presented. *p < .05. **p < .001.

Hypotheses regarding relationships between O, C, A, and DSM-IV disorder dimensions were partially supported. Consistent with prediction, low C had a significant negative path to MDD (γ = −.11). Although C was also associated with GAD, the positive nature of this path was not in line with prediction (γ = .12). Inconsistent with study hypotheses, O was not associated with MDD and unexpectedly had a significant negative path to PD/AG (γ = −.18). As expected, A did not predict any DSM-IV disorder dimension.

Discussion

Prior latent structural examinations of the NEO FFI have relied on PCA, EFA, and CFA procedures in nonclinical samples. The present study extends the extant literature by being the first to examine the NEO FFI in a large clinical sample using ESEM. Consistent with study hypotheses, ESEMs supported the anticipated five-factor structure of NEO FFI. Notably, the goodness-of-fit statistics from the ESEM solutions in the current study (e.g., Sample 1: TLI = .89, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .05) are nearly identical to those reported in Marsh et al.’s (in press) ESEM examination of the NEO FFI in a population-based sample (TLI = .89, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .03). The interfactor correlations ranged from .00 to −.32, which are also similar to Marsh et al.’s findings (in press; rs = −.01 to −.21) and consistent with Big-Five theory (i.e., the five domains are relatively orthogonal).

Although these results support the utilization of the NEO FFI in clinical samples using ESEM procedures, it is noteworthy that there were some cross-loadings (i.e., items with multiple loadings ≥ .30) and some items with nonsalient primary loadings (i.e., items with all loadings < .30). In addition to being consistent with prior research (e.g., McCrae & Costa, 2004), these findings were not surprising given that the NEO FFI items were not selected with the specific aim of maximizing a clean factor structure (i.e., items were chosen based on item correlations with respective domain scores rather than results from factor analysis). Nonetheless, consideration of results from factor analytic studies (i.e., EFA and ESEM) is important in maximizing the construct validity of the NEO FFI (i.e., ensuring that items are assessing the domain of interest). For instance, including items based exclusively on correlations with their respective domain score ignores the possibility that some items may assess multiple domains (e.g., salient cross-loadings in factor analysis).

Although some of the items that functioned poorly in the current study are the same as those identified as weak by McCrae and Costa’s (2004) review (e.g., Items 3, 28, and 28), others are not (e.g., Items 18, 33, and 49). Given that much of McCrae and Costa’s review focused on evaluations of the NEO FFI in nonclinical samples, this may indicate that certain items function well in normative populations but poorly in clinical samples. Collectively, these findings highlight the need for some revisions to the NEO FFI, particularly for items intended to measure the O domain (five of the six items with nonsalient loadings were purported indicators of O). Unfortunately, prior attempts to replace NEO FFI items have been largely unsuccessful (e.g., McCrae & Costa, 2004).

ESEM allowed for an evaluation of the relations between the FFM domains and dimensions of anxiety and depressive disorders adjusting for measurement error. Whereas prior research has relied on dichotomous representations of DSM disorders (e.g., Bienvenu et al., 2001, 2004; Tackett et al., 2008; Trull & Sher, 1994), the current study is the first to evaluate how the FFM predicts dimensions of anxiety and depression in a large clinical sample. Consistent with prior studies (e.g., Bienvenu et al., 2004; Trull & Sher, 1994) and study hypotheses, A was not associated with any of the emotional disorder dimensions. Whereas N was positively associated with GAD, OCD, SOC, and MDD, E was inversely related to only SOC and MDD. This is in line with theory and research that has implicated heightened levels of negative emotional states (i.e., high N) as salient across the emotional disorders while decreased positive emotionality, sociability, and activity levels (i.e., low E) are uniquely related to SOC and depression (e.g., Bienvenu et al., 2001; Brown, 2007; Brown et al., 1998). Moreover, N demonstrated its strongest zero-order and structural relationships with dimensions of GAD and MDD, consistent with conceptualizations of these disorders as strong pathological expressions of negative affect (e.g., Brown et al., 1998; Brown & Barlow, 2009).

The structural model also found C to be significantly associated with dimensions of MDD and GAD. The negative path between C and MDD is in line with prior research (e.g., Trull & Sher, 1994) and indicates that a lack of self-control in organization and planning is associated with more severe levels of depression. This may indicate the relevance of C to the maintenance of depression; poor organization and planning (i.e., low C) may lead to stress in various domains (e.g., poor performance in work, school, or relationships), thereby increasing or maintaining symptoms of depression. This is in line with the hypothesis that C may influence mood (McCrae & Costa, 1991) and supports arguments for the consideration of conscientiousness in conceptualizations of depression (Anderson & McLean, 1997). The negative path between C and MDD is also consistent with Kendler and Myers (2010), who found C and MDD to demonstrate a significant inverse genetic association (i.e., a modest amount of the genetic risk for MDD was predicted by C).

Despite a trivial zero-order correlation between C and GAD (r = −.02), C was significantly associated with GAD in the structural model (i.e., a suppressor effect). However, the positive nature of this path opposes study hypotheses and indicates that greater self-control in organization/planning uniquely predicts dimensions of GAD only after holding the four remaining FFM domains and their relationships with dimensions of PD/AG, SOC, MDD, and OCD constant. Although one study had previously linked low C to a lifetime diagnosis of GAD (Bienvenu et al., 2004), the positive structural path from C to GAD is consistent with clinical features of the disorder. For example, perhaps high C reflects perfectionist tendencies (e.g., excessive planning or preparation as an avoidance strategy; Brown & Barlow, 2009) caused by an intolerance of uncertainty (Dugas, Gagnon, Ladouceur, & Freeston, 1998). Collectively, this suggests that greater self-control in planning and organization is uniquely associated with the frequency and uncontrollability of anxiety and tension over minor matters, work/school, family, and health during the course of clinical disorders.

Other hypotheses were also not supported by the structural model. For example, high O was not associated with current severity of MDD symptoms at the zero-order or structural level, contrasting prior studies using the NEO FFI that have found high O to be associated with a lifetime diagnosis of MDD (Trull & Sher, 1994). This finding is perhaps not surprising given that other studies have failed to fully support a relationship between O and MDD (i.e., MDD may only be related to O at the facet level; Bienvenu et al., 2001, 2004). Additional research is needed to clarify how, if at all, O and MDD are meaningfully related. Moreover, although high N (and possibly low E) was expected to predict dimensions of PD/AG, the structural model failed to support these relationships. Instead, low O and high E were found to uniquely predict dimensions of this disorder. The present study is the first of our knowledge to demonstrate a relationship between O and PD/AG. Nonetheless, this relationship is somewhat intuitive; lower levels of curiosity and higher levels of conservativeness (i.e., low O) may be related to the extent of situational apprehension and avoidance due to a fear of having panic. In contrast, the positive path between E and PD/AG is less interpretable. Although this finding may indicate high E to be salient in PD/AG severity, this seems unlikely given that prior research has consistently found no relationship between E and PD and an inverse relationship between E and AG (e.g., Bienvenu et al., 2001, 2004; Carrera et al., 2006; Rosellini et al., 2010).

Despite strengths in sampling and methodology (e.g., first evaluation of the NEO FFI with ESEM in a clinical sample; clinician ratings for key features of DSM-IV disorders), the present study is not without limitations. The sample was predominately Caucasian, limiting the generalizability of the study findings to other racial groups. Moreover, data from the longer NEO instruments (e.g., NEO PI or NEO PI-R) would have improved the study by allowing us to evaluate possible replacement items for the poorly functioning NEO FFI items. Finally, the cross- sectional design of the present study precluded us from conducting a more extensive examination of the nature of associations between the FFM domains and DSM-IV disorder dimensions (e.g., temporal directional relationships among the FFM domains and the DSM dimensions, see Widiger & Trull, 1992).

Future research should aim to improve the NEO FFI by replacing poorly functioning items (e.g., generating new items or using other items from the NEO PI or NEO PI-R). Given the plethora of studies that have found the NEO PI and NEO PI-R to perform poorly in CFA (e.g., Church & Burke, 1994; Parker et al., 1993), it would be useful to evaluate these instruments using ESEM. As the NEO instruments continue to gain structural support in clinical samples (e.g., Bagby et al., 1999), perhaps the FFM could be usefully incorporated into DSM-V. Empirical support for the relationship between the FFM and personality pathology has even led to proposals that Axis II should be replaced with a dimensional system based on the FFM (e.g., Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009). Utilization of the NEO instruments could offer advantages in pursuit of this integration (e.g., ease of use for clinicians, researchers, and patients). Moreover, although the current personality dimensions proposed for DSM-V (APA, 2010) have yet to be validated (i.e., an assessment instrument has yet to be developed), four of the six dimensions may be at least partially captured by FFM domains as measure by the NEO FFI or other NEO instruments. For instance, the proposed traits of negative emotionality and introversion likely closely reflect N and E, respectively. Likewise, whereas disinhibition (i.e., impulsivity, irresponsibility) might be related to C, compulsivity (i.e., rigidity, risk aversion) may capture O. However, the proposed traits of antagonism (i.e., callousness, narcissism, aggression) and schizotypy (i.e., unusual perceptions, eccentricity) may not be strongly related to any of the FFM domains.

In addition, studies are needed to further evaluate the nature of the relationships between FFM domains and the anxiety and depressive disorders. For example, longitudinal research following individuals from premorbid periods through the experience and remission of clinical disorders is needed to clarify if personality increases risk for psychopathology or if psychopathology changes personality. Moreover, although a few studies have examined how the FFM domains predict some clinical outcomes (e.g., in depression, Bagby et al., 2008; without consideration of diagnosis, Miller, 1991), additional research is needed to examine longitudinal relations between the FFM and other emotional disorders (e.g., C and GAD).

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: The study was supported by Grant MH039096 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Although the NEO FFI items were modeled as continuous ables in our analyses to replicate the model estimator used by Marsh et al. (in press), it is noteworthy that items using a 5-point Likert-type scale may also be conceptualized as ordinal variables. With this issue in mind, we also analyzed the data from Samples 1 and 2 using a categorical estimator (robust weighted least squares). The results of these solutions were virtually identical to those reported in this article (e.g., goodness of fit, strength and pattern of factor loadings, and error covariances).

A CFA (with correlated residuals) was conducted in Sample 1 to examine fit relative to ESEM. Consistent with prior findings, the CFA model resulted in poor model fit χ2(1643) = 5664.371, p < .001, SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .05 (CFit p = .62), TLI = .78, CFI = .80.

A CFA (with correlated residuals) was conducted in Sample 2 to examine fit relative to ESEM. Consistent with prior findings, the CFA model resulted in poor model fit, χ2(1643) = 5681.340, p < .001, SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .05 (CFit p = .58), TLI = .77, CFI = .79.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aluja A, Garcia O, Garcia LF, Seisdedos N. Invariance of the “NEO-PI-R” factor structure across exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38:1879–1889. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. rev. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. Text rev. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Reformulation of personality disorders in DSM-V. Washington, DC: Author; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/PersonalityandPersonalityDisorders.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KW, McLean PD. Conscientiousness in depression: Tendencies, predictive utility, and longitudinal stability. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1997;21:223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Hobbs MJ, Borkovec TD, Beesdo K, Craske MG, Heimberg RG, … Stanley MA. Generalized worry disorder: A review of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder and options for DSM-V. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:134–147. doi: 10.1002/da.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2009;16:397–438. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby RM, Costa PT, McCrae RR, Livesley WJ, Kennedy SH, Levitan RD, … Young LT. Replicating the five factor model of personality in a psychiatric sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;27:1135–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby RM, Quilty LC, Segal Z, McBride C, Kennedy SH, Costa PT. Personality and differential treatment response in major depression: A randomized controlled trial - comparing cognitive-behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;53:361–370. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beauducel A, Whittmann WW. Simulation study on fit indexes in CFA based on data with slightly distorted simple structure. Structural Equation Modeling. 2005;12:41–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Brown C, Samuels JF, Liang K, Costa PT, Eaton WW, Nestadt G. Normal personality traits and comorbidity among phobic, panic, and major depressive disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2001;102:73–85. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Samuels JF, Costa PT, Reti IM, Eaton WW, Nestadt G. Anxiety and depressive disorders and the five-factor model of personality: A higher- and lower-order personality trait investigation in a community sample. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;20:92–97. doi: 10.1002/da.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Temporal course and structural relationships among dimensions of temperament and DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorder constructs. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:313–328. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. Categorical vs. dimensional classification of mental disorders in DSM-V and beyond. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:551–556. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. A proposal for a dimensional classification system based on the shared features of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for assessment and treatment. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:256–271. doi: 10.1037/a0016608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:179–192. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:585–599. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera M, Herran A, Ramirez ML, Ayestaran A, Sierra-Biddle D, Hoyuela F, … Vazquez-Barquero VL. Personality traits in early phases of panic disorder: Implications on the presence of agoraphobia, clinical severity, and short-term outcome. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;114:417–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell RB. The descriptions and measurement of personality. Yonkers, NY: World Book; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Church TA, Burke PJ. Exploratory and confirmatory tests of the big five and Tellegen’s three- and four-dimensional models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:93–114. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Bagby RM, Herbst JF, McCrae RR. Personality self-reports are concurrently reliable and valid during acute depressive episodes. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;89:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. The NEO-PI/NEO-FFI manual supplement. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO PI-R professional manual: Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Widiger TA. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L) New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dugas MJ, Gagnon F, Ladouceur R, Freeston MH. Generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary test of a conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:215–226. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan V, Deary I, Austin E. The NEO-FFI: Emerging British norms and an item-level analysis suggest N, A, and C are more reliable than O and E. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;29:907–920. [Google Scholar]

- Holden RR, Fekken GC. The NEO Five-Factor Inventory in a Canadian context: Psychometric properties for a sample of university women. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;17:441–444. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Judge TA, Ilies R. Relationship of personality to performance motivation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87:797–807. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Myers J. The genetic and environmental relationship between major depression and the five-factor model of personality. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:801–806. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau K-T, Grayson D. Goodness of fit evaluation in structural equation modeling. In: Maydeu-Olivares A, McCardle J, editors. Psychometrics: A Festschrift to Roderick P. McDonald. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 275–340. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau KT, Wen Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralising Hu & Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:320–341. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Lüdtke O, Muthén B, Asparouhov T, Morin AJS, Trautwein U, Nagengast B. A new look at the big-five factor structure through exploratory structural equation modeling. Psychological Assessment. doi: 10.1037/a0019227. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Muthén B, Asparouhov T, Lüdtke O, Robitzsch A, Morin AJS, Trautwein U. Exploratory structural equation modeling, integrating CFA and EFA: Application to students’ evaluation of university teaching. Structural Equation Modeling. 2009;16:439–476. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. Adding liebe and arbeit: The full five-factor model and well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1991;17:227–232. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. A contemplated revision of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36:587–596. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Zonderman AB, Costa PT, Bond MH, Paunonen SV. Evaluating replicability of factors in the revised NEO Personality Inventory: Confirmatory factor analysis versus procrustes rotation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:552–566. [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR. The psychotherapeutic utility of the five- factor model of personality: A clinician’s experience. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1991;57:415–433. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5703_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus 5.2 [Computer software] Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Noftle EE, Shaver PR. Attachment dimensions and the big five personality traits: Associations and comparative ability to predict relationship quality. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:179–208. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JDA, Bagby RM, Summerfeldt LJ. Confirmatory factor analysis of the revised NEO Personality Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences. 1993;4:463–466. [Google Scholar]

- Parker W, Stumpf H. A validation of the five-factor model of personality in academically talented youth across observers and instruments. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;25:1005–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Fraley RC, Roberts BW, Trzesniewski KH. A longitudinal study of personality change in young adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:617–640. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.694157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosellini AJ, Lawrence AE, Meyer JF, Brown TA. The effects of extraverted temperament on agoraphobia in panic disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:420–426. doi: 10.1037/a0018614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottman BM, Ahn W, Sanislow CA, Kim NS. Can clinicians recognize DSM-IV personality disorders from five-factor model descriptions of patient cases? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:427–433. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08070972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. Clinician’s judgments of clinical utility: A comparison of the DSM-IV and five-factor models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:298–308. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1326–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz N, Hartkamp N, Baldini C, Rollnik J, Tress W. Psychometric properties of the German version of the NEO-FFI in psychosomatic outpatients. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:713–722. [Google Scholar]

- Seibert SE, Kraimer ML. The five-factor model of personality and career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2001;58:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Quilty LC, Sellbom M, Rector NA, Bagby RM. Additional evidence for a quantitative hierarchical model of mood and anxiety disorders for DSM-V: The context of personality structure. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:812–825. doi: 10.1037/a0013795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ. Relationship between the five-factor model of personality and Axis I disorders in a non-clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:350–360. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassend O, Skrondal A. Validation of the NEO Personality Inventory and the five-factor model: Can findings from exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis be reconciled? European Journal of Personality. 1997;11:147–166. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Carey G. Positive and negative affect and their relevance to the study of psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:346–353. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Mullins-Sweatt SN. Five-factor model of personality disorders: A proposal for DSM-V. Annual Reviews of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5:197–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Trull TJ. Personality and psychopathology: An application of the five-factor model. Journal of Personality. 1992;60:363–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu KD, Clark LA, Watson D. Relations between obsessive-compulsive disorder and personality: Beyond Axis I–Axis II comorbidity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20:695–717. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]