Abstract

Objective

To investigate the risk of hearing loss progression in each ear among children with unilateral hearing loss associated with ipsilateral bony cochlear nerve canal (BCNC) stenosis.

Setting

Tertiary pediatric referral center

Patients

Children diagnosed with unilateral hearing loss who had undergone temporal bone computed tomography imaging and had at least six months of follow-up audiometric testing were identified from a prospective audiological database.

Interventions

Two pediatric radiologists blinded to affected ear evaluated imaging for temporal bone anomalies and measured bony cochlear canal width independently. All available audiograms were reviewed, and air conduction thresholds were documented.

Main outcome measure

Progression of hearing loss was defined by a 10 dB increase in air conduction pure-tone average.

Results

128 children met inclusion criteria. Of these, 54 (42%) had a temporal bone anomaly, and 22 (17%) had ipsilateral BCNC stenosis. At 12 months, rates of progression in the ipsilateral ear were as follows: 12% among those without a temporal bone anomaly, 13% among those with a temporal bone anomaly, and 17% among those with BCNC stenosis. Children with BCNC stenosis had a significantly greater risk of progression in their ipsilateral ear compared to children with no stenosis: hazard ratio 2.17, 95% CI (1.01, 4.66), p-value 0.046. When we compared children with BCNC stenosis to those with normal temporal bone imaging, we found that the children with stenosis had nearly 2 times greater risk estimate for progression, but this difference did not reach significance, HR 1.9, CI (0.8, 4.3), p = 0.1. No children with BCNC stenosis developed hearing loss in their contralateral year by 12 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

Children with bony cochlear nerve canal stenosis may be at increased risk for progression in their ipsilateral ear. Audiometric and medical follow-up for these children should be considered.

Introduction

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the temporal bone is a high-yield diagnostic tool to assess underlying anatomic abnormalities among children with unilateral hearing loss (UHL)1. Imaging can provide information to assist with management and counseling2. While MRI may be the more sensitive test to detect abnormalities such as cochlear nerve deficiency3, CT has benefits as an imaging modality because it is more affordable, provides better assessment of bony structures, and is less likely to require sedation4. CT detects abnormalities in approximately 30–40 percent of patients with hearing loss5,6. However, it is important for providers to weigh the benefits of obtaining an anatomic diagnosis with potential risks of sedation or radiation exposure, particularly among children with mild or unilateral hearing loss (UHL).

As we gain understanding of the prognostic significance of various temporal bone anomalies, radiographic studies can be justified as a way to counsel families more effectively. For example, enlarged vestibular aqueduct (EVA) has become a well-described anomaly that is among the most common CT abnormalities identified in children with hearing loss7. Studies have found that between 20–40 percent of children with EVA demonstrate progression of their hearing loss8,9. However, the natural history of other temporal bone anomalies has not been as well characterized.

Bony cochlear nerve canal (BCNC) stenosis is a recognized temporal bone anomaly associated with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). In 2000, Fatterpekar et al. correlated degree of SNHL with BCNC width, even in the absence of other temporal bone anomalies10. Additional studies have confirmed an inverse correlation between BCNC diameter and pure tone average (PTA)11. Yi et al. found that 28 of 29 children with a BCNC width smaller than 1.4 mm had severe to profound hearing loss in the affected ear12. BCNC stenosis has become recognized as among the most common radiographic findings in children with unilateral hearing loss13.

However, the mechanism for hearing loss in these patients is unknown and no causal relationship between BCNC stenosis and SNHL has been proven. One possible association is that SNHL in patients with BCNC stenosis is due to a fixed deficit of the auditory nerve fibers passing through the canal14. If so, then we might expect a stable hearing loss and less likelihood of progression over time when compared to children with other anomalies such as EVA. On the other hand, it might be that BCNC stenosis reflects a more global developmental deficit involving the cochlea itself. In which case, children may be at risk of progression in ipsilateral, or even contralateral, ears. Therefore, providers may face difficulties when attempting to counsel families of children with BCNC stenosis who have residual, aidable hearing15.

The primary objective of this study was to determine if children with BCNC stenosis have an increased risk of progressive hearing loss when compared to children with UHL who had other temporal bone anomalies and those who had normal imaging. This comparison allowed us to carry out the secondary objective of this study, which was to describe rates of progression in ipsilateral and contralateral ears among children with UHL.

Methods

This study received institutional review board approval from Seattle Children’s Hospital (Seattle, WA), a pediatric tertiary care facility. The institution’s audiogram database was queried to identify all children with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) from January 2007 to July 2013. Unilateral SNHL was defined as bone-conduction three-frequency (500, 1000 and 2000 Hz) pure tone average ≥ 30 dB SPL in the abnormal ear and ≤ 20 dB SPL in the contralateral ear. Identified cases were then cross-referenced with radiology records to find those who had temporal bone CT imaging. All available audiograms were reviewed for each child. Exclusion criteria included the following: lack of available CT imaging, less than 6 months of audiometric follow-up, or presence of an acquired hearing loss for reasons such as temporal bone fracture or ototoxicity.

Two pediatric radiologists, blinded to affected ear, reviewed all temporal bone imaging. They evaluated the width of bony cochlear nerve canal using criteria established by Fatterpekar et al10. Measurements were made on axial images with a plane parallel to the infraorbitomeatal line using a picture archiving and communications system (PACS). Images were reconstructed using a high spatial-resolution bone algorithm with individual magnification of the right and left temporal bones of 10x. The width of the bony cochlear nerve canal was measured at its midpoint along the inner portion of the bony walls perpendicular to the canal axis. The radiologists also documented other temporal bone anomalies, evaluating the semicircular canals, vestibule, cochlea, vestibular aqueduct, cochlear aqueduct, round window, oval window, facial nerve, carotid artery and jugular bulb.

Children were then grouped into categories based on presence of the following imaging findings: normal imaging, presence of BCNC stenosis, presence of EVA, or presence of any other temporal bone anomaly. Based on previously published literature12, a width of less than or equal to 1.4 mm was established as the threshold for diagnosing a child with bony cochlear nerve canal stenosis. Children found to have radiographic abnormality of the vestibulocochlear or middle ear structures were classified as having a temporal bone anomaly. Overall rates of progression at 6 months and 12 months of follow-up were documented for each group in both the affected and unaffected ears. Based on criteria utilized in previous studies, hearing loss progression was defined as a 10 dB increase in PTA16. Data was also collected on various demographic characteristics, including age at diagnosis and length of follow-up.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the overall sample as well as within the subgroups based on temporal bone imaging. Means and standard deviations were computed for continuous variables. Counts and percentages were computed for categorical variables. Comparisons were made to identify any significant differences in demographic characteristics among the groups.

When considering risk of progression, length of follow-up is a potential confounding variable. Children who are followed over longer periods of time will have more opportunity to demonstrate progression. In retrospective studies, there will be variable lengths of follow-up among children, and so it is not appropriate to simply evaluate overall rates of progression without correcting for time. A hazard analysis adjusts for this potential bias; therefore, we fit a Cox proportional hazards regression model17 to examine the relationship between BCNC stenosis and hearing loss progression (Model 1).

The Cox regression model makes the proportional hazards assumption, which implies that comparisons between groups can be made based on the hazard ratio without consideration of the time-varying baseline hazard function. Standard ways of assessing the proportional hazards assumption did not indicate that this assumption was violated in our dataset. We used the Cox regression models to make unadjusted comparisons between binary groups (e.g. children with BCNC stenosis versus children without BCNC stenosis). In this sense, the Cox regression models are similar to non-regression based approaches such as Kaplan-Meier survival curves. However, the Cox model has the advantage that it gives us an easily calculated measure of effect size (the hazard ratio).

The outcome of interest for our primary model was hearing loss progression in the ipsilateral ear; the exposure of interest was the presence of BCNC stenosis. We also explored whether age at diagnosis or baseline PTA threshold were potential confounders. When we reviewed these characteristics, we did not find significant differences between children with or without BCNC stenosis; therefore, we did not include these in the model.

In addition to this primary comparison, we fit several secondary models. The outcome of interest in these additional models was also hearing loss progression in the ipsilateral ear. We compared risk of progression among the following groups: children with BCNC stenosis versus those with normal temporal bone imaging (Model 2), children with any temporal bone anomaly versus those with normal imaging (Model 3), and children with EVA versus those without EVA (Model 4).

The hazard ratio was used as the measure of association in all models. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the hazard ratios from these regression models were computed. Tests of the null hypothesis that the hazard ratio is equal to 1 were performed. All hypothesis testing was performed at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

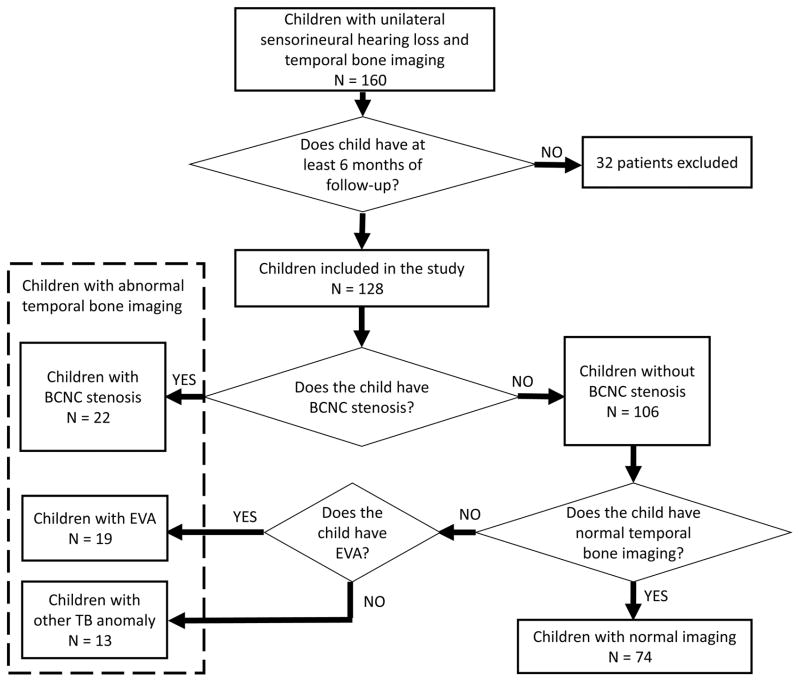

The initial audiometric database query identified 341 children with unilateral hearing loss. After the exclusion of children with acquired hearing loss, there were 160 children who had unilateral sensorineural hearing loss and temporal bone CT imaging. Of those, 128 children were included in this study because they had at least 6 months of audiometric follow-up. Twenty-two children had BCNC stenosis (average CNC width 0.76 mm) and 106 children had normal BCNC width (average CNC width 2.1 mm). Children were divided into groups for analysis based upon imaging characteristics, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of imaging characteristics of children with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss

There were no significant differences in initial PTA threshold or age at diagnosis between these groups. Average age at time of initial audiogram was 8 years for children without stenosis and 6 years for children with stenosis; the difference was not significant, p = 0.08. Baseline pure-tone average (PTA) was 70.8 ± 24.7 dB in children without stenosis and 75.6 ± 21.0 dB in children with stenosis, p = 0.24. Final PTA average was 71 ± 25 dB in children without BCNC stenosis and 89.4 ± 24.1 dB in children with BCNC stenosis. Descriptive statistics for the cohort of children are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of children with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss

| Overall (n = 128) | BCNC Stenosis (n = 22) | Any Temporal Bone Anomaly (n = 54) | Normal Temporal Bone Imaging (n = 74) | EVA (n = 19) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age at 1st Audiogram | 7.7 | 3.9 | 6.0 | 2.9 | 6.3 | 3.2 | 8.6 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 2.4 |

| Baseline PTA (Deaf Ear) | 70.6 | 23.9 | 75.6 | 21.0 | 72.1 | 22.1 | 69.22 | 25.5 | 60.5 | 21.0 |

| Final PTA (Deaf Ear) | 73.6 | 25.6 | 89.4 | 24.1 | 80.7 | 23.8 | 68.9 | 27.1 | 60.6 | 14.5 |

| Follow-up (Days) | 1126.0 | 704.4 | 952.9 | 650.1 | 1158.0 | 674.5 | 1091.1 | 730.6 | 1332.4 | 736.3 |

| Gender (Percent Male) | 0.51 | - | 0.55 | - | 0.46 | - | 0.54 | - | 0.38 | - |

BCNC = Bony cochlear nerve canal

EVA = Enlarged vestibular aqueduct

PTA = Pure tone average

Among all 128 children with USNHL, 42 (32.8%) demonstrated progression in their ipsilateral ear at some point in time over the course of follow-up. Length of follow-up was variable among the different groups: Children with EVA had the longest period of observation at 1332.4 days ± 736.3 while children with BCNC stenosis had the shortest period at 952.9 days ± 650.1.

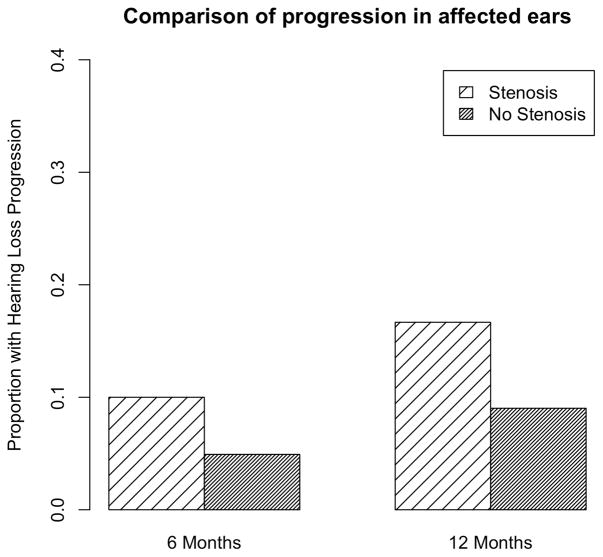

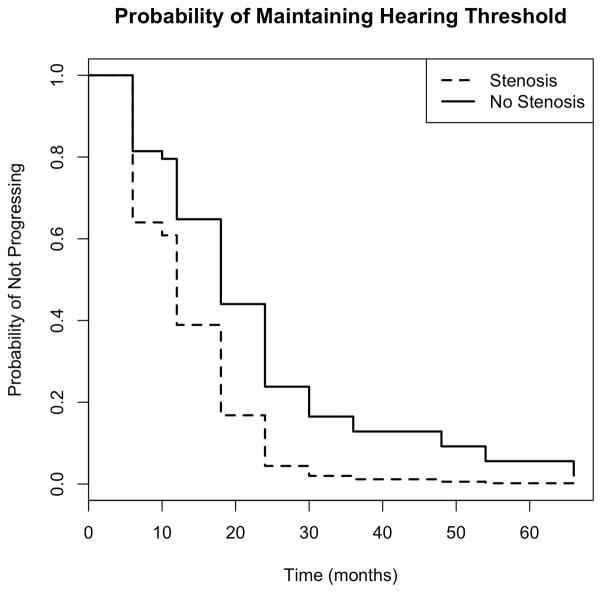

Among children with BCNC stenosis, 2 (10%) had progressed by 6 months and 4 (18%) had progressed by 12 months. Rates of progression were lower among children without BCNC stenosis: 6 (6%) by 6 months and 12 (11%) by 12 months, see Figure 2. To determine whether this difference in progression was significant, we performed a hazard analysis, see Figure 3. The survival curves presented in Figure 2 are based on Cox regression models. We examined non-parametric survival curves based on Kaplan-Meier estimates and they did not differ substantially from the survival curves shown in Figure 3. The estimated hazard rate for progression to hearing loss in the ipsilateral ear was 2.17 times greater for subjects with stenosis compared to those without stenosis, (95% CI: 1.01, 4.66); this difference was significant, p = 0.046. We also determined whether the magnitude of difference in baseline and final PTA between children with and without stenosis was statistically significant using a two-sample t-test (unequal variance). When we compared the difference between final PTA and baseline PTA between children with BCNC stenosis and without BCNC stenosis, we calculated an estimated difference of 9.28 dB between the two groups, 95% CI 1.82, 16.75. This difference was statistically significant, p= 0.017.

Figure 2. Comparison of proportion of children with hearing loss progression in their affected ears among children with and without BCNC stenosis.

A greater proportion of children with BCNC stenosis demonstrated progression.

Figure 3. Comparison of hearing threshold stability over time in affected ears among children with and without BCNC stenosis.

The estimated hazard rate for progression of hearing loss in the ipsilateral ear was 2.17 times greater for subjects with stenosis compared to those without stenosis, (95% CI: 1.01, 4.66)

We performed a similar analysis comparing rates of development of hearing loss in the contralateral ear over time. No children with BCNC stenosis developed hearing loss in the contralateral ear by 12 months. Among children without BCNC stenosis, 3 (3%) developed contralateral hearing loss by 12 months. The difference was not significant with hazard analysis, p = 0.6.

We then performed additional secondary analyses, investigating rates of hearing loss progression among children with USNHL who had temporal bone anomalies in general, and those who had normal temporal bone imaging, see Table 2. Fifty-four children were identified as having a congenital temporal bone anomaly of the bony labyrinth, middle ear or internal auditory canal (including BCNC stenosis); of these children, 7 (13%) progressed by 12 months. Of the 74 children with normal temporal bone imaging, 9 (12%) progressed by 12 months. There were also 19 children with ipsilateral EVA; of which, 1 (7%) had progressed by 12 months. Overall, 7 (37%) of children with EVA demonstrated ipsilateral progression over the entire course of the study.

Table 2.

Proportional rates of ipsilateral progression among children with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss

| Overall (n=128) | BCNC stenosis (n = 22) | Any temporal bone anomaly (n = 54) | Normal temporal bone imaging (n=74) | EVA (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion (%) | Proportion (%) | Proportion (%) | Proportion (%) | Proportion (%) | |

| Progression in 6 months | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.0 |

| Progression in 12 months | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

BCNC = Bony cochlear nerve canal

EVA = Enlarged vestibular aqueduct

Hazard analyses were carried out to compare progression risk among the various subgroups, see Table 3. When we compared children with BCNC stenosis to those with normal temporal bone imaging, we found that the children with stenosis had nearly 2 times greater risk estimate for progression, but this difference did not reach significance, HR 1.9, CI (0.8, 4.3), p = 0.1. When we compared children with any congenital temporal bone anomaly to those with normal imaging, the risk estimate for progression in the ipsilateral ear was attenuated, HR 1.3, CI (0.7, 2.6), p = 0.4. Finally, although the overall proportion of progression was higher among children with EVA, 37%, compared to the entire group, 33%, we did not find a statistically significant difference in risk of progression between these two groups, HR 1, CI (0.4, 2.3), p = 0.9. Too few children demonstrated progression in the contralateral ear to allow for meaningful analysis.

Table 3.

Risk estimates of ipsilateral hearing loss progression among children with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss

| Exposure | Comparison group | Risk estimate for progression (hazard ratio) | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children with BCNC stenosis | Children without BCNC stenosis | 2.16 | (1.01, 4.66) | 0.0464 |

| Children with BCNC stenosis | Children with normal temporal bone | 1.9 | (0.84, 4.30) | 0.123 |

| Children with any temporal bone abnormality | Children with normal temporal bone | 1.35 | (0.71, 2.56) | 0.367 |

| Children with EVA | Children without EVA | 0.97 | (0.4, 2.34) | 0.94 |

BCNC = Bony cochlear nerve canal

EVA = Enlarged vestibular aqueduct

CI = Confidence interval

Discussion

BCNC stenosis is now a well-recognized temporal bone anomaly associated with ipsilateral USNHL, but our understanding of the natural history of this condition is limited. Kono et al. evaluated CT image measurements of the BCNC, IAC, bony vestibular nerve canal, and labyrinthine facial nerve canal in children with unilateral SNHL11 and found an association between hearing loss and BCNC stenosis even in the setting of otherwise normal IAC and temporal bone anatomy. Their study suggested that BCNC stenosis alone may be sufficient to produce hearing loss, but exactly how this occurs is not well understood.

Questions even remain as to the diagnostic criteria of BCNC stenosis. Several studies have attempted to characterize typical BCNC widths using CT measurements and cadaveric specimens, with normal BCNC diameters averaging between 1.9 – 2.1mm18. Studies have proposed differing criteria for the diagnosis of BCNC stenosis, including a width measured in the axial plane of less than 1.7 mm11, less than 1.5 mm19, and less than 1.4 mm20.

Based on our previous analysis15, we defined cochlear nerve canal stenosis as a diameter of ≤1.4 mm in the axial plane, near the lower limit of the thresholds presented in other investigations. In this study, 17% (22 of 128) of children with unilateral SNHL were found to have BCNC stenosis; this percentage is smaller than other reports13, likely due to our tighter diagnostic criteria.

The results of our study indicate that, at the time of diagnosis, children with BCNC stenosis have similar hearing thresholds as other children with unilateral SNHL, yet they have a statistically greater risk of progression compared to children without BCNC stenosis. This increased risk was not identified in the contralateral ear. It is also important to note that overall one-third of the children observed in this study demonstrated progression in their ipsilateral ear regardless of their diagnosis. This finding implies that all patients with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss are potentially at risk of progression and should receive both audiometric and medical follow-up.

There is increasing appreciation for the impact of USNHL on speech and language development. UHL is estimated to affect about 1% of school-aged children and adolescents, and the prevalence may be increasing21,22. UHL was traditionally thought to permit appropriate development, but clinicians and other providers have increasingly recognized that UHL is associated with difficulty for sound localization23, increased rates of grade failure24, substandard speech and language outcomes25, and additional social barriers26.

Imaging has a particularly high diagnostic yield among children with USNHL. There are a range of temporal bone anomalies potentially associated with SNHL, including EVA, cochlear dysplasia, BCNC or IAC stenosis, and others; nearly half of children with isolated USNHL will receive a diagnosis as to their hearing loss on radiographic imaging. Over a decade ago, Mafong et al. evaluated children with unidentified etiologies of SNHL and found that about 40% of the children have abnormal temporal bone anatomy7. Our study found a similar proportion to have an ipsilateral temporal bone anomaly.

Identification of anatomic abnormalities can help providers counsel families effectively regarding their child’s risk of progressive impairment5. This has been highlighted in the example of EVA. EVA syndrome was one of the first described temporal bone anomalies, and it has been associated with fluctuating and progressive hearing loss27. While investigating EVA, Arcand et al. identified progressive hearing loss in children with enlarged aqueducts, but also noted progressive hearing loss in those with vestibular aqueducts of normal dimensions and no inner ear malformations 9. Interestingly, when compared to previous EVA studies, we found a similar rate of overall progression (37%)28, but we did not find a statistically significant difference in risk of progression between children with and without EVA. The children with EVA in this study did have a longer length of follow-up time, possibly indicating that they were monitored more closely after receiving the diagnosis. The hazard analysis allows us to control for differences in length of follow-up, so ultimately we did not identify a significant difference in ipsilateral progression between the children with and without EVA in this study.

We were also able to explore the average magnitude of ipsilateral hearing loss progression over time. We found an average PTA increase of 3 dB in the ipsilateral ear among the group overall; however the PTA change was higher at 13.8 dB in the children with BCNC stenosis, and 8.6 dB in children with any temporal bone abnormality. Children with normal temporal bone imaging had essentially the same average PTA across the observation period of the study.

The vestibulocochlear nerve lies within the IAC and transmits primarily afferent auditory and vestibular signals to the brainstem. The BCNC connects the fundus of the internal auditory canal to the cochlea. The cell bodies of the cochlear nerve reside in the spiral ganglion of the modiolus, with axonal projections passing from the base of the cochlea into the IAC. Because these nerve fibers must pass from the modiolus to the IAC, it is often hypothesized that a narrow BCNC is evidence of a deficient cochlear nerve. Stenosis could reflect cochlear nerve deficiency, however, it could also be a manifestation of a broader embryologic insult to the developing inner ear.

The pathogenesis of stenotic cochlear nerve canals may be further understood by studying the histopathological and functional deficiency of nerve hypoplasia and auditory canal narrowing. At three weeks gestational age, the inner ear begins developing from two ectodermal thickenings surrounding the rhombencephalic neural tube. These ectodermal plates eventually invaginate to form the otocyst, the precursor membranous labyrinth, composed of an auditory and vestibular pouch 29. As the otic vesicle forms, a collection of cells detach from the ectoderm, producing the statoacoustic ganglion antecedent to the auditory and vestibular ganglion. Neurites from the ganglia are then re-directed back into the developing membranous labyrinth and are further refined to form the distal, afferent auditory axons. Synchronously, mesenchymal tissue enveloping the otocyst condenses and begins to ossify, eventually creating the bony labyrinth. It is proposed that trophic growth factors from the membranous labyrinth act on the maturing statoacoustic neurites and mesenchyme, which develop into the cochlear nerve and surrounding bony architecture, respectively 30. Histologically, laboratory research has substantiated otocyst induction of both chondrogenesis and neurogenesis 31. Thus, BCNC stenosis, as seen on imaging, may be a manifestation of a developmental insult to the otocyst with loss of appropriate growth factor signaling. Therefore, BCNC stenosis, IAC narrowing, and cochlear nerve deficiency may be interrelated.

Both CNC and IAC stenosis have been recommended as relative contraindications for cochlear implantation 32. However, stenosis of these structures does not always indicate cochlear nerve deficiency. MRI studies of the cochlear nerve have found that BCNC stenosis, as visualized on CT, is not necessarily an accurate indicator of nerve deficiency, and cochlear nerve deficiency can occur in ears with normal bony architecture3. Additional research is needed to characterize the complex interrelationship between BCNC and IAC stenosis and cochlear nerve development.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize the risk of hearing loss progression associated with BCNC stenosis. It suggests that these patients are at ongoing risk of progression, perhaps due to a developmental insult to the vestibulocochlear structures, rather than a fixed lesion of the cochlear nerve. Our study found that patients with BCNC stenosis are at increased risk for their hearing loss to progress more quickly and potentially more aggressively, as demonstrated by the statistically significant difference in magnitude of progression over time. Based on these findings, we recommend continued monitoring of hearing loss, particularly for the ipsilateral ear. Children who qualify should also be offered early intervention for educational support and perhaps a trial of hearing rehabilitation.

This study has important limitations. It is a retrospective study with variable lengths of follow-up for all the children. There is the possibility that we have overestimated progression rates because children who experience a decline in their hearing are probably more likely to undergo serial audiograms. Fortunately, we are able to adjust for variable rates of follow-up using the hazard analysis method. In addition, the sample size was small for some of our subgroups, such as children with BCNC stenosis or EVA, which limits our analytic power when making comparisons. The small size of the sample of interest may have affected the conclusion of our study, and a repeat of this analysis with a larger group would be of interest in the future. We also had too few children with contralateral progression to be able to perform a meaningful analysis of risk to contralateral ears.

Finally, we note that, although Figure 3 shows the probability of maintaining hearing threshold decreasing to zero over time in both groups, this does not contradict the previously reported percentage of children (32%) who demonstrated progression over the course of the study. Rather, this effect is due to the presence of censoring, which affects the number of individuals considered to be at risk for progression over time. As a result, discrepancies can occur between the time-varying estimate of the probability of maintaining hearing threshold and the overall proportion of observed progressions. By performing a hazard analysis, we are controlling for variable rates of follow-up among the children in this study.

Conclusion

This study suggests that, among children with USNHL, the presence of BCNC stenosis may be associated with a risk of progression in the ipsilateral, but not contralateral, ear. We found this difference to be statistically significant when we compared children with BCNC stenosis to children without stenosis (even if they had other temporal bone anomalies); however, the difference did not reach significance when we compared children with BCNC stenosis to only children with normal temporal bone imaging. Overall, one-third of children with USNHL were found to progress in their ipsilateral ear over the course of the study. Children with USNHL, including those with BCNC stenosis, should receive appropriate monitoring over time with supportive measures as indicated.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Patricia Purcell is a resident/research fellow at University of Washington. Her time was partially supported by an Institutional National Research Service Award for Research Training in Otolaryngology (2T32DC000018) from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

The authors would like to thank Rose Jones-Goodrich for providing administrative support for this project.

Footnotes

This study was presented for the American Otological Society at Combined Otolaryngology Spring Meetings (COSM), Chicago, IL, May 20–22, 2016.

References

- 1.Simons JP, Mandell DL, Arjmand EM. Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Pediatric Unilateral and Asymmetric Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Arch Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 2006;132(2):186–192. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman AB, Guillory R, Ramakrishnaiah RH, Frank R, Gluth MB, Richter GT, Dornhoffer JL. Risk analysis of unilateral severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77(7):1128–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adunka OF, Jewells V, Buchman CA. Value of Computed Tomography in the Evaluation of Children with Cochlear Nerve Deficiency. Otology and Neurotology. 2007;28:597–604. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000281804.36574.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeMarcantonio M, Choo DI. Radiographic evaluation of children with hearing loss. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2015;48(6):913–32. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song J, Choi HG, Oh SH, Chang SO, Kim CS, Lee JH. Unilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Children: The Importance of Temporal Bone Computed Tomography and Audiometric Follow-Up. Otology and Neurotology. 2009;30:604–608. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181ab9185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preciado DA, Lim L, Cohen AP, Madden C, Myer D, Ngo C, et al. A Diagnostic Paradigm for Childhood Idiopathic Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. 2004;131(6):804–809. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.06.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mafong DD, Shin EJ, Lalwani AK. Use of laboratory evaluation and radiologic imaging in the diagnostic evaluation of children with sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madden C, Halstead M, Benton C, Greinwald J, Choo D. Enlarged vestibular aqueduct syndrome in the pediatric population. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24(4):625–32. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arcand P, Desrosiers M, Dube J, Abela A. The Large Vestibular Aqueduct Syndrome and Sensorineural Hearing Loss in the Pediatric Population. Journal of Otolaryngology. 1991;20(4):247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fatterpekar GM, Mukherji SK, Alley J, Lin Y, Castillo M. Hypoplasia of the Bony Canal for the Cochlear Nerve in Patients with Congenital Sensorineural Hearing Loss: Initial Observations. Radiology. 2000;215(1):243–246. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.1.r00ap36243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kono T. Computed Tomographic Features of the Bony Canal of the Cochlear Nerve in Pediatric Patients with Unilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Radiation Medicine. 2008;26(3):115–119. doi: 10.1007/s11604-007-0204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi JS, Lim HW, Kang BC, Park SY, Park HJ, Lee KS. Proportion of Bony Cochlear Nerve Canal Anomalies in Unilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2013;77:530–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masuda S, Usui S, Matsunaga T. High Prevalence of Inner-ear and/or Internal Auditory Canal Malformations in Children with Unilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2013;77:228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemmens CS, Guidi J, Caroff A, et al. Unilateral cochlear nerve deficiency in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(2):318–25. doi: 10.1177/0194599813487681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purcell PL, Iwata AJ, Phillips GS, Paladin AM, Sie KC, Horn DL. Bony cochlear nerve canal stenosis and speech discrimination in pediatric unilateral hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(7):1691–6. doi: 10.1002/lary.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackler RK, De La Cruz A. The large vestibular aqueduct syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1989;99(12):1238–42. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198912000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1972;34(2):187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fatterpekar GM, Mukherji SK, Lin Y, Alley JG, Stone JA, Castillo M. Normal canals at the fundus of the internal auditory canal: CT evaluation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23(5):776–80. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199909000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komatsubara S, Haruta A, Nagano Y, Kodama T. Evaluation of cochlear nerve imaging in severe congenital sensorineural hearing loss. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2007;69(3):198–202. doi: 10.1159/000099231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stjernholm C, Muren C. Dimensions of the cochlear nerve canal: A radioanatomic investigation. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122(1):43–8. doi: 10.1080/00016480252775724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DJ, Gomez-Marin O, Lee HM. Prevalence of unilateral hearing loss in children: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey II and the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ear Hear. 1998;19(4):329–32. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199808000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shargorodsky J, Curhan SG, Curhan GC, Eavey R. Change in prevalence of hearing loss in US adolescents. JAMA. 2010;304(7):772–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnstone PM, Nabelek AK, Robertson VS. Sound localization acuity in children with unilateral hearing loss who wear a hearing aid in the impaired ear. J Am Acad Audiol. 2010;21(8):522–34. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.21.8.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bess FH, Tharpe AM. Unilateral hearing impairment in children. Pediatrics. 1984;74(2):206–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lieu JE, Tye-Murray N, Karzon RK, Piccirillo JF. Unilateral hearing loss is associated with worse speech-language scores in children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):e1348–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borton SA, Mauze E, Lieu JE. Quality of life in children with unilateral hearing loss: a pilot study. Am J Audiol. 2010;19(1):61–72. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2010/07-0043). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alemi AS, Chan DK. Progressive hearing loss and head trauma in enlarged vestibular aqueduct: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153(4):512–7. doi: 10.1177/0194599815596343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noordman BJ, van Beeck Calkoen E, Witte B, Goverts T, Hensen E, Merkus P. Prognostic factors for sudden drops in hearing level after minor head injury in patients with an enlarged vestibular aqueduct: a meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(1):4–11. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mafee MF, Charletta D, Kumar A, Belmont H. Large vestibular aqueduct and congenital sensorineural hearing loss. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;13(2):805–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackler RK, Luxford WM, House WF. Congenital malformations of the inner ear: a classification based on embryogenesis. Laryngoscope. 1987;97(3 Pt 2 Suppl 40):2–14. doi: 10.1002/lary.5540971301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van de Water TR, Ruben RJ. Neurotrophic interactions during in vitro development of the inner ear. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93(6 Pt 1):558–64. doi: 10.1177/000348948409300606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valero J, Blaser S, Papsin BC, James AL, Gordon KA. Electrophysiologic and behavioral outcomes of cochlear implantation in children with auditory nerve hypoplasia. Ear Hear. 2012;33(1):3–18. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3182263460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]