OPINION STATEMENT

Substance use disorders (SUD) can be considered developmental disorders in light of their frequent origins in substance initiation during adolescence. Cross-sectional functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of adolescent substance users or adolescents with SUD have indicated aberrations in brain structures or circuits implicated in motivation, self-control, and mood-regulation. However, attributing these differences to the neurotoxicological effects of chronic substance use has been problematic in that these circuits are also aberrant in at-risk children, such as those with prenatal substance exposure, externalizing disorders (such as conduct disorder), or prodromal internalizing disorders such as depression. To better isolate the effects of substance exposure on the adolescent brain, the newly-launched Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, will follow the neurodevelopmental trajectories of over 11,000 American 9/10-year-olds for 10 years, into emerging adulthood. This study will provide a rich open-access dataset on longitudinal interactions of neurodevelopment, environmental exposures, and childhood psychopathology that confer addiction risk. The ABCD twin study will further clarify genetic versus experiential influences (e.g., substance use) on neurodevelopmental and psychosocial outcomes. Neurocircuitry thought to regulate mood and behavior has been directly normalized by administration of psychoactive medications and by cognitive therapies in adults. Because of this, we contend that ABCD project data will be a crucial resource for prevention and treatment of SUD in adolescence because its cutting-edge neuroimaging and childhood assessments hold potential for discovery of additional targetable brain differences earlier in development that are prognostic of (or aberrant in) SUD. The ABCD sample size will also have the power to illuminate how sex differences, environmental interactions and other individual differences interact with neurodevelopment to inform treatment in different groups of adolescents.

Keywords: Adolescence, Impulsivity, Development, Addiction, Depression, Neuroimaging

Introduction

Substance use disorder (SUD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder when symptoms onset during adolescence. For example, lifetime likelihood of developing alcohol use disorder (AUD) increases as a function of how early the individual began alcohol use [1]. Longitudinal cohorts have identified subsets of youth in whom early onset is predictive of heavier use or SUD at follow-up, for alcohol [2], as well as for nicotine [3] and cannabis [4]. For this reason, prevention of substance use in adolescence is critical for optimal health and psychosocial outcomes.

Behavioral [5] and psychopharmacological [6][7] interventions have been shown to normalize functioning of brain circuits for behavior and emotion control. Accordingly, we contend that state-of-the-art neuroimaging in a large longitudinal study of youth will have the statistical power to identify additional subgroups for whom certain interventions may be more likely to be beneficial in either preventing or treating SUD. This in turn will enable: i) neurobiologically-informed psychiatric medication of pediatric populations (i.e., personalized medicine); and ii) identification of novel neurocircuit markers for psychiatric drug discovery. Target patient subgroups could be defined by pubertal development, sex, temperament, neurobehavioral deficits, environmental vulnerabilities, or genetic factors, by virtue of their relationships with precise neurocircuit function. In this overview, we broadly describe motivational etiologies of SUD, the neurocircuit aberrations thought to underlie these etiologies, and how effective clinical interventions alter these neurocircuits. We conclude with a description of the new ABCD study as a platform for developmental neurocircuit discovery.

Multiple neurobiological pathways to SUD

Improving prevention and treatment of SUD requires greater understanding of how individual differences in substance use motives stem from neurocircuit-driven temperament characteristics [8]. Individual differences in pathways to addiction have been most extensively studied in alcohol use disorder (AUD). Motives for initial heavy drinking vary between positively-reinforced (thrill-seeking) and negatively-reinforced (self-medication of negative affect)[9][10]. Indeed, in AUD, “type A”[11] or “type “1[12] are characterized by later age of onset and negative-affect-related drinking. In contrast, “type B”[11] or “type 2”[12] are predominantly male, with earlier onset, frequently in tandem with antisocial behaviors. These typologies are thought to result from divergent genetically-influenced neurobehavioral traits such as vulnerability to stress [13]. Motivation for abuse of other substances may also be divided along similar lines [14]; different motives could have distinct and shared neurocircuit underpinnings.

Neurodevelopmental underpinnings of the negatively-reinforced pathway to SUD

Relief from stress, anxiety and depression is a powerful motivator for substance use in many adolescents [14,15]; children with affective symptoms are at significant risk for development of SUD [16][17]. By extension, these youth should show exaggerated reactivity in circuits that govern negative mood reactions. Lindquist et al [18] recently meta-analyzed functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) experiments that entailed presentation of emotionally-valenced stimuli or other transient mood inductions. This did not indicate separate networks for positive versus negative emotional reactions. Rather, the same brain regions (anterior insula, amygdala, pregenual and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and lateral parietal cortex) are invoked for both positive and negative valence, with slight biases toward negativity in left amygdala and anterior insula [18]. This network of emotion-evoked brain structures bears a striking spatial resemblance to the “salience network” (SN) identified by resting-state fMRI [19]. The SN is thought to calibrate behavioral responses to environmental threats or opportunities [20].

Enhanced connectivity between SN nodes and the “default mode” network (DMN) is characteristic of depression (in adults), as is enhanced functional connectivity between DMN regions [21]. DMN activity increases in the absence of external task demands [22] and during self-referential processing [23]. Therefore, enhanced intra-DMN and SN-DMN connectivity could be a signature of propensity for emotionally-painful rumination [24] that could prompt substance use. In a structural convergence of SN abnormalities, a recent meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry (VBM) studies of psychiatric populations revealed that gray matter (GM) reductions (normalized for whole-brain size) in bilateral insula and ACC were common to all mental illness (including SUD)[25]. Some of these abnormalities have also been found in at-risk children due to family history of AUD [26]. These findings imply that a source of GM abnormalities of SN structures described in cross-sectional VBM studies of alcoholics [27] may be premorbid characteristics leading to AUD.

Collectively, this suggests that early neurodevelopmental aberrations of SN structure and connectivity in childhood and adolescence may be markers for proneness toward negative affect leading to SUD. For example, Lippard et al [28] recently reported that among mid-adolescents with bipolar disorder, lower GM volume in insula, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) at baseline predicted greater incidence of SUD symptomatology at 6-year follow-up. Task-elicited activation of SN nodes, such as increased reactivity of amygdala to emotional faces in borderline personality disorder [29] or in depressed adolescents [30], are also candidate markers of SUD risk. Schuckit et al [31] recently reported that increased SN (anterior insula) reactivity to emotional faces in emerging adults age 20 was predictive of alcohol problems at 5-year follow-up. In sum, longitudinal assessment of SN neurocircuitry (both before and after substance initiation) may yield additional insights into the relationship between substance use and neurodevelopment.

Neurodevelopmental underpinnings of the positively-reinforced pathway to SUD

Most research on brain-based contributors to substance use in adolescence has concerned the positively-reinforced pathway [32]. Binge drinking in high school is thought to result from positive expectancies about alcohol effects [33], and positive expectancies about alcohol effects have been linked to both questionnaire [34,35] and brain markers [36] of increased impulsivity in adolescents or emerging adults. Impulsivity is a multi-faceted trait [37] that confers sensitivity to positive reinforcement, and has been conceptually divided into rapid-response and decision-based subtypes [38]. The former operates on short time-scales by “acting without thinking,” and has been operationalized as increased commission errors (CE) to non-target stimuli or poor ability to terminate an already-initiated motor response in signal-detection tasks. Decision-based impulsivity is usually operationalized by exaggerated preference for small but immediate rewards over larger but delayed rewards.

A prevailing theory attributes substance use to impulsivity resulting from overactive approach-motivation neurocircuitry to cues for drug rewards that is insufficiently regulated by behavioral-control circuits in prefrontal cortex (PFC)[39]. Patients with PFC lesions [40], as well as fMRI studies [41] show that the PFC regulates incentivized behavior. For example, dorsolateral PFC (dlPFC) is recruited by decisions to defer gratification [42,43]. The dlPFC is thought to send information to ventromesial PFC (vmPFC) to integrate the total effective value of an incentive [42]. With respect to delayed rewards, dlPFC is recruited during the imagination of self in future outcomes, using autobiographical memory to construct envisioned scenes [44]. Impaired dlPFC neurodevelopment could therefore provide an impulsivity-based risk marker for SUD [45].

Evidence for the impulsivity-based account of SUD risk is abundant in neurobehavioral [46] and functional neuroimaging [32] literature on children with conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder, who are at risk for SUD [47]. Laboratory behavioral studies suggest that hypersensitivity to rewards and ambivalence toward punishments is characteristic of these disorders [48,49]. Setting aside diagnoses, longitudinal studies support a mechanistic consequence of these behavioral tendencies for SUD directly. For example, the link between sensation-seeking personality at 14 and binge drinking at 16 was mediated by reward sensitivity in an incentivized go-nogo task [50]. Fernie et al [51] reported that both rapid-response impulsivity and decision-based impulsivity in 12- and 13-year olds was predictive of higher alcohol use in 6-month follow-up. Neuroimaging signatures of reward sensitivity and reduced impulse control may also be direct risk-factors for SUD [52,53]. For example, exaggerated mesolimbic responses to reward deliveries are characteristic of sensation-seeking youth [54,55], youth with externalizing disorders [56], as well as individuals with SUD [57]. Conversely, both externalizing disorders [32] and SUD [58] are associated with blunted recruitment of inhibitory or error-monitoring neurocircuitry of the ACC and anterior insula/inferolateral PFC (ilPFC) by non-substance-related inhibition tasks, where this blunted recruitment has correlated with impaired control over drinking [59].

Finally, many children show both internalizing and externalizing symptomatology as risk factors for SUD. On a structural level, a meta-analysis of VBM studies showed that youth with conduct problems (especially with early-onset) showed reduced insula and amygdala GM volumes [60] akin to that seen in adult general mental illness [25]. Furthermore, McTeague and colleagues [61] highlighted how even mood disorders are characterized by impaired cognitive control. They suggested that a common decrement in a “multiple demand” network can jointly underlie failure to regulate emotion as well as behavior. This may be manifested in bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder, which are defined by both impulsivity and mood dysregulation.

The hypothesis that inhibitory function is a unitary, cross-cutting cognitive trait is suggested by factor analysis of within-subject performance across a variety of different cognitive tasks, in a “unity and diversity” model [62]. In variations of this model, a common latent factor accounts for shared variance in performance across all tasks, but with additional specific latent factors for task-switching and information-updating [62]. Importantly, this general factor essentially accounted for inhibitory control performance, because successful performance of most tasks requires inhibition of non-desired responses or resistance to distracting information. This general factor is thought [61] to be instantiated in the set of regions that are routinely activated by nearly every cognitive task studied in fMRI [63,64]. This set of “task-positive” regions includes several nodes of the SN (ACC, anterior insula/ilPFC)[25], with the addition of dlPFC and superior parietal lobe. Recruitment of these commonly-activated regions (perhaps as network “hubs”) may simply be a minimum requirement for task performance, such that individual differences in cognition lie in connections to those hubs [62]. How the parcellation of cognitive performance changes across neurodevelopment is less understood, however.

Cognitive control circuitry is frequently enhanced by psychiatric medications or by cognitive behavioral therapy

In sum, many neurocircuit correlates of internalizing and externalizing traits could serve as points of intervention to either prevent or treat SUD. Not surprisingly, several fMRI studies of brain changes following chronic psychotropic medication or cognitive behavioral therapy sessions indicate that these interventions alter functional activation or connectivity of structures relevant for cognitive control. A prime example would be the extensively-replicated finding that chronic stimulant administration to ADHD subjects increases activity in the right ilPFC/anterior insula SN “hotspot” for behavioral inhibition [65]. Another would be the effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) to reduce amygdala/SN reactivity to social threat stimuli, both acutely in controls, and after chronic administration in patients with anxiety disorders [7]. Similarly, dialectic behavioral therapy normalized exaggerated amygdala response to emotional faces in subjects with borderline personality disorder [29].

In general, those medications that show clinical effectiveness tend to increase fMRI signatures of recruitment or connectivity of task-relevant structures (or the “task-on” network), or alternatively to decrease activity of task-irrelevant networks (such as DMN)[6]. This is in line with speculation that cognitive impairment in many psychiatric disorders stems from aberrant “toggling” between task-on and task-off (DMN) networks [66]. Finally, review of executive control training interventions in middle childhood and adolescence [5] indicates that whereas strategy-based training (such as using visual cues in the environment to remember oratory) does not benefit more distal cognitive skills, process-based training of fine-grained executive skills (such as maintaining information in working memory) is more likely to improve performance in unrelated tasks. This also argues for the utility of targeting nodes of a cross-cutting executive control network, such that enhancement of one component of this network could indirectly lower impulsivity conducive to SUD [67,68]. Importantly, individual differences in these circuits at baseline are predictive of medication response [7]. For example, in patients with major depression, greater connectivity from insula at baseline was predictive of response to cognitive behavioral therapy [69].

The new ABCD longitudinal study of adolescent development holds potential to better inform prevention and treatment of adolescent SUD

The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, will provide an unprecedented dataset to enable investigation of individual and/or developmental differences in neurocircuit-based risk for SUD, as well as longitudinal correlates of substance exposure effects. The study launched in September 2016, and will recruit and assess a nationally-representative sample of 11,500 9–10 year olds (including 1,600 twins) recruited at 21 US sites. The study will follow these children for 10 years. The sampling/data collection component of the University of Michigan’s Survey Research Center guide the probability sampling of the participants by demographically targeting schools surrounding each collection site for singleton recruitment.

Multi-modal MRI assessments conducted at baseline and every two years thereafter are central to the project. (For a full listing of all baseline ABCD assessments, please see https://abcdstudy.org/scientists-protocol.html). First, high-resolution structural imaging will enable computation of volumes of sub-cortical structures (e.g., hippocampus, accumbens, amygdala), along with measurements of cortical thickness and surface area at over 300,000 sites on the brain. Using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), the size, structure and other properties of white matter (WM) fiber tracts will be measured. The project will use fMRI to capture resting-state functional connectivity, as well as brain recruitment by rewards, emotional stimuli, working memory demands, and behavioral inhibition, using a time-efficient selection of tasks that will be administered in counterbalanced order across subjects.

First, the Monetary Incentive Delay (MID) Task [70] measures brain signatures of anticipation and receipt of rewards and losses. In brief, participants are presented with incentive cues, which are trained in advance to be associated with four possible gains or losses of real money (+$0.20, +$5.00, −$0.20, −$5.00) or $0. This is followed by a fixation delay, then a dynamically-manipulated target period during which subjects must respond to gain or avoid losing money. Feedback of gain or loss is then given on each trial. The Stop Signal Task (SST)[71] is administered to assess impulse control. The SST presents visual stimuli to which the subject must respond. However, a minority of these stimuli are followed ~250 ms later by a stop signal, such that the child must inhibit an already-initiated response. Finally, the MRI session includes an Emotional N-back task of working memory, wherein the subject must attend to a series of visual stimuli, and respond whether or not each image that matches a reference image directly (0-back) or matches the image shown two images prior (2-back). Notably, the stimuli to be displayed and held in working memory are scenes, as well fearful, neutral, and happy faces, to provide a value-added contrast of reactivity to emotional information. The scan is followed by a post-scan probe of memory for N-back stimuli, to assess potential decrements in hippocampus-mediated encoding and recall associated with alcohol and marijuana use [72]. Importantly, these tasks will collectively invoke the SN and executive control circuits discussed above in every child, from mid-childhood until emerging adulthood.

The neuroimaging battery is supplemented by a set of offline neurocognitive tasks administered by iPad. These measures are largely derived from the NIH Toolbox [73], and include list sorting, oral reading, pattern comparison, picture sequence and picture vocabulary tests. Mental rotation is probed with the Little Man task. Of special relevance to SUD risk, rapid-response impulsivity is probed in the flanker task, decision-based impulsivity is probed in a cash-choice task, and cognitive rigidity is probed in the dimensional change card sort task. The Rey Auditory Verbal Learning test, Matrix Reasoning and other tasks round out this comprehensive neurocognitive assessment battery. These tests will collectively enable assessment of the factor structure of cognitive abilities across development, as they relate to structure and function of specific brain networks.

The child’s mood symptomatology is self-reported in affective disorder modules of the computerized Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-5 (KSADS-5). Substance use histories will be assessed in age-appropriate timeline follow-back (TLFB) interviews, using pictures and calendar cues. Other self-report measures include impulsivity questionnaires from the NIH-supported PhenX toolkit. Use of open-access consensus instruments will facilitate harmonization with other projects.

Extensive REDCap-based computerized parent interviews collect information about the child’s sleep, pubertal development, screen-time, household rules and household substance use, family conflict, neighborhood safety, and a host of other environmental factors that may influence substance use initiation, SUD and/or brain development. In addition, parents complete computerized versions of the Child Behavior Checklist and the full KSADS-5 about the child.

A third main type of data is derived from biospecimens, primarily saliva. Presently, blood collection is limited to the four twin sites, but will be expanded to other sites in future assessments. Biospecimens will inform about substance use and pubertal stage, and will enable genetic and epigenetic analyses. A hair sample will be used to assess cannabis constituents in a subset of participants. In the future we plan to obtain an instant-read of cotinine (NicAlert) to assess recent nicotine use or exposure to smoked tobacco. Illumina have offered full genome sequencing of all ABCD study participants. Ultimately, the ABCD study will provide a very large genetically informative dataset able to identify new loci associated with neuroimaging phenotypes, psychopathology, substance use and its risk factors. Beyond whole genome sequencing, an epigenetic assay will evaluate the impact of development, stress and substance use on methylation and gene expression. When available, baby teeth are collected to test for prenatal and lifetime exposure to metals and drugs.

In alternate (non-scan) years, participants will visit each data-collection site for a shorter assessment. This “off-year” assessment is slated to entail interviews and questionnaires about major life events/stressors, changes in substance use or other mental health status, such as onset of psychosis symptoms. We will also use off-year assessments to track subject perceptions of substance availability, intention to use, and peer use. Upon evidence of substance initiation, follow-on measures will address subjective responses to alcohol, tobacco and marijuana; craving and tolerance, and substance expectancies. We will also collect biospecimens to monitor physiological changes with puberty. Finally, at each 6-month interim between on-site assessments, a telephone interview of the child will more briefly assess onset or other changes in substance use.

Study of twins in the ABCD project will yield additional critical information

The ABCD study will collect data from 1,600 twins at four sites with active twin research centers: Virginia Commonwealth University, University of Colorado at Boulder, University of Minnesota, and Washington University, St. Louis. Additional twin pairs (~200) are expected to be recruited at other sites, as approximately one birth in 100 is twins. Twin studies are able to estimate the relative impact of genetic and environmental factors on individual differences in the population. While the ABCD twins will be used to map the heritability of different parts of the brain [74], this is not the main goal. Rather, we focus on the fact that MZ twin pairs share both 100% of their genetic variants and many salient features of the environment, from neighborhood to schools, parenting style and, e.g., the availability of illicit drugs. Although twins may not share 100% of, e.g., exposure to harsh parenting, they likely share a great deal of it, and therefore a participant’s cotwin is an excellent matched control. DZ twins share on average 50% of their genome with their twin, but for any trait with a substantial heritability, a DZ cotwin represents a much closer type of control than matching on age and other demographic data.

Studies of twins add unique scientific value. Randomized clinical trials that compare groups that have received different treatments are valuable for causal inference, but may have limited scope. When considering substance use and neurodevelopment, ethical concerns prevent such experimental approaches, and we may lack knowledge about exactly which factors in a person’s life history are relevant to the outcome. A study of discordant twins can, however, yield similar information. Known as the cotwin control (CTC) method, it simply regresses intrapair differences on, e.g., neuroimaging phenotypes onto intrapair differences in substance use. Because twins are concordant for genotype and shared environmental factors, they are excluded as putative causal agents behind such differences. It is also necessary to include pair sums in the regression, because a pair difference of, e.g., a standard deviation carries different information depending on the twins’ deviations from the population mean.

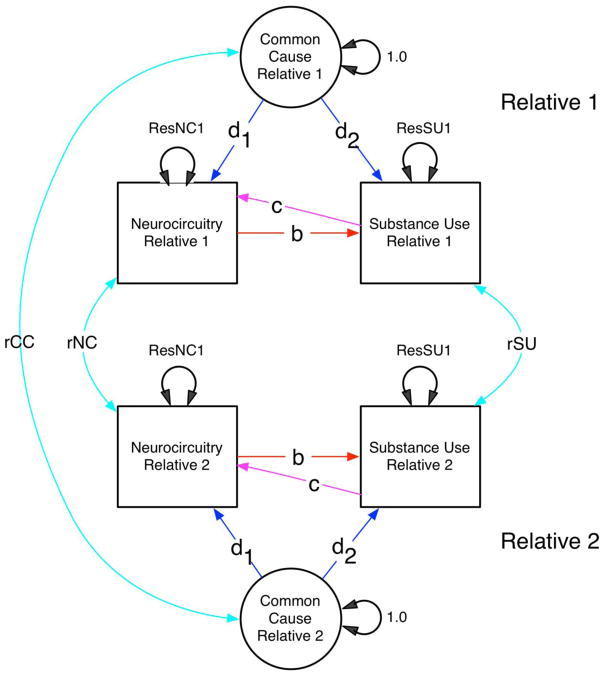

Model-fitting analyses of data collected from relatives have become very popular in the past 25–30 years. Structural equation models (SEMs) subsume a wide variety of statistical methods within a simple mathematical framework. One reason for its broad appeal is that models can be specified with either equations (typically matrix algebra) or a path diagram. A second feature is that most models can be fitted by maximum likelihood, which is efficient. To model data from MZ and DZ twins, a multiple-group SEM is used, because the model-predicted covariances of MZ and DZ twins differ [75]. Figure 1 shows a path diagram for several forms of association between substance use and a neurocircuitry measure of interest. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Path diagram showing measured neurocircuitry and substance use variables (boxes) and a latent common cause factor, for each of two relatives. Relatives may covary (cyan two-headed arrows) via paths rCC, rNC and rSU. Within each individual, neurocircuitry may affect substance use (path b), or vice-versa (path c), or the two may covary due to common causes (paths d1 and d2). Submodels with subsets of the paths b, c, d1 and d1 fixed to zero are used to test alternative hypotheses of causation.

Methods for analysis of repeated measures from twins have been available for over 30 years [76]. First, latent growth curve methods are readily extended to data from MZ and DZ twins by partitioning latent growth factors (such as level, slope and curvature) into genetic and environmental components of variance. The Markov model permits estimation of genetic and environmental contributions to developmental change of a single trait (e.g., neurocircuit function) over time. For each of the variance components (A = additive genetic factors, C= environmental factors shared between cotwins, and E = environmental factors unique to each cotwin), three types of variation may be modeled: a factor common to all occasions; new variance for each occasion; and transmission from one occasion to the next. Mathematically, growth curve models are suitable for application to multivariate twin data and long time series. They can offer novel insights into processes such as relapse and rebound effects - known phenomena in substance use patterns over time. In light of a key goal of the ABCD project to investigate causal effects of substance use on neurodevelopment, use of the cotwin design can therefore approximate the unique environmental impact of substance exposure on brain while controlling for genetically-programmed neurodevelopment.

Conclusions

The ABCD study will illuminate with unprecedented clarity the interplay across adolescent development between substance use and neurocircuitry that both confers risk of SUD and is affected by chronic alcohol and other substance use. In light of extant evidence that therapeutic interventions normalize these circuits in clinical responders, understanding developmental differences and environmental interactions with these circuits will be crucial for drug discovery and for better targeting of therapies in childhood and adolescence. Importantly, ABCD data will be accessible to qualified investigators, to expand the utility of this dataset for discovery science.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was prepared under the salary support to JMB and MCN afforded by cooperative agreement 1U01DA041120.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards:

Conflict of interest

James M. Bjork declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Lisa K. Straub declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Rosellen G. Provost declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Michael C. Neale declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

Recruitment and procedures of each site and the coordinating center of the ABCD study are continually monitored by the ABCD External Advisory Board and the Bioethics and Medical Oversight advisory panel, and have been approved by either the local site Institutional Review Board (IRB) or by local IRB reliance agreements with the central IRB of the University of California-San Diego (site of the ABCD Coordinating Center).

References

Recently published papers of particular interest have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:739–46. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newton-Howes G, Boden JM. Relation between age of first drinking and mental health and alcohol and drug disorders in adulthood: evidence from a 35-year cohort study. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2016;111:637–44. doi: 10.1111/add.13230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose JS, Lee C-T, Dierker LC, Selya AS, Mermelstein RJ. Adolescent nicotine dependence symptom profiles and risk for future daily smoking. Addict Behav. 2012;37:1093–100. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein M, Hill KG, Nevell AM, Guttmannova K, Bailey JA, Abbott RD, et al. Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence into adulthood: Environmental and individual correlates. Dev Psychol. 2015;51:1650–63. doi: 10.1037/dev0000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karbach J, Unger K. Executive control training from middle childhood to adolescence. Front Psychol. 2014;5:390. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •6.van Amelsvoort T, Hernaus D. Effect of Pharmacological Interventions on the Fronto-Cingulo-Parietal Cognitive Control Network in Psychiatric Disorders: A Transdiagnostic Systematic Review of fMRI Studies. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:82. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00082. This review of non-stimulant medication effects on fMRI signals demonstrates how even across drug mechanisms, effective medications tend to increase activity of general “task-on” networks and mute default-mode networks, which sheds light both on drug action as well as network abnormalities in psychiatric disorders. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nathan PJ, Phan KL, Harmer CJ, Mehta MA, Bullmore ET. Increasing pharmacological knowledge about human neurological and psychiatric disorders through functional neuroimaging and its application in drug discovery. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2014;14:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Litten RZ, Egli M, Heilig M, Cui C, Fertig JB, Ryan ML, et al. Medications development to treat alcohol dependence: a vision for the next decade. Addict Biol. 2012;17:513–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1844–57. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolton JM, Robinson J, Sareen J. Self-medication of mood disorders with alcohol and drugs in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Affect Disord. 2009;115:367–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babor TF, Hofmann M, DelBoca FK, Hesselbrock V, Meyer RE, Dolinsky ZS, et al. Types of alcoholics, I. Evidence for an empirically derived typology based on indicators of vulnerability and severity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:599–608. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilligan SB, Reich T, Cloninger CR. Etiologic heterogeneity in alcoholism. Genet Epidemiol. 1987;4:395–414. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370040602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heilig M, Goldman D, Berrettini W, O’Brien CP. Pharmacogenetic approaches to the treatment of alcohol addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:670–84. doi: 10.1038/nrn3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blevins CE, Banes KE, Stephens RS, Walker DD, Roffman RA. Motives for marijuana use among heavy-using high school students: An analysis of structure and utility of the Comprehensive Marijuana Motives Questionnaire. Addict Behav. 2016;57:42–7. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pang RD, Farrahi L, Glazier S, Sussman S, Leventhal AM. Depressive symptoms, negative urgency and substance use initiation in adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;144:225–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.09.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu P, Bird HR, Liu X, Fan B, Fuller C, Shen S, et al. Childhood depressive symptoms and early onset of alcohol use. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1907–15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Angold A, Costello EJ. The prospective relation between dimensions of anxiety and the initiation of adolescent alcohol use. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30:316–26. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindquist KA, Satpute AB, Wager TD, Weber J, Barrett LF. The Brain Basis of Positive and Negative Affect: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis of the Human Neuroimaging Literature. Cereb Cortex N Y N 1991. 2016;26:1910–22. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole DM, Smith SM, Beckmann CF. Advances and pitfalls in the analysis and interpretation of resting-state FMRI data. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010;4:8. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters SK, Dunlop K, Downar J. Cortico-Striatal-Thalamic Loop Circuits of the Salience Network: A Central Pathway in Psychiatric Disease and Treatment. Front Syst Neurosci. 2016;10:104. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2016.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •21.Mulders PC, van Eijndhoven PF, Schene AH, Beckmann CF, Tendolkar I. Resting-state functional connectivity in major depressive disorder: A review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;56:330–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.07.014. This is a useful review of converging evidence that a disorder prone to rumination is characterized by robust communication between nodes of a network that is activated by self-referential thinking. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:700–11. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews-Hanna JR, Reidler JS, Sepulcre J, Poulin R, Buckner RL. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain’s default network. Neuron. 2010;65:550–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton JP, Farmer M, Fogelman P, Gotlib IH. Depressive Rumination, the Default-Mode Network, and the Dark Matter of Clinical Neuroscience. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:224–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •25.Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, Jiang Y, Chang A, Jones-Hagata LB, et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:305–15. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2206. This seminal review of fMRI gray matter volume studies identified structural correlates of what might be a common neurodevelopmental aberration/pathway that underscores a dysregulated brain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benegal V, Antony G, Venkatasubramanian G, Jayakumar PN. Gray matter volume abnormalities and externalizing symptoms in subjects at high risk for alcohol dependence. Addict Biol. 2007;12:122–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •27.Yang X, Tian F, Zhang H, Zeng J, Chen T, Wang S, et al. Cortical and subcortical gray matter shrinkage in alcohol-use disorders: a voxel-based meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;66:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.034. This review dutifully summarizes findings of gray matter reductions that correlate with diagnoses of AUD, which should be interpreted with the caveat that many reductions have also been found in frequently comorbid mood disorders. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lippard ETC, Mazure CM, Johnston JAY, Spencer L, Weathers J, Pittman B, et al. Brain circuitry associated with the development of substance use in bipolar disorder and preliminary evidence for sexual dimorphism in adolescents. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95:777–91. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman M, Carpenter D, Tang CY, Goldstein KE, Avedon J, Fernandez N, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy alters emotion regulation and amygdala activity in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;57:108–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang TT, Simmons AN, Matthews SC, Tapert SF, Frank GK, Max JE, et al. Adolescents with major depression demonstrate increased amygdala activation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:42–51. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201001000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Paulus MP, Tapert SF, Simmons AN, Tolentino NJ, et al. The Ability of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Predict Heavy Drinking and Alcohol Problems 5 Years Later. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:206–13. doi: 10.1111/acer.12935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Squeglia LM, Cservenka A. Adolescence and Drug Use Vulnerability: Findings from Neuroimaging. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2017;13:164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgenstern M, Isensee B, Sargent JD, Hanewinkel R. Attitudes as mediators of the longitudinal association between alcohol advertising and youth drinking. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:610–6. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harnett PH, Lynch SJ, Gullo MJ, Dawe S, Loxton N. Personality, cognition and hazardous drinking: Support for the 2-Component Approach to Reinforcing Substances Model. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2945–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kazemi DM, Flowers C, Shou Q, Levine MJ, Van Horn KR. Personality risk for alcohol consequences among college freshmen. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2014;52:38–45. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20140310-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson KG, Schweinsburg A, Paulus MP, Brown SA, Tapert S. Examining personality and alcohol expectancies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) with adolescents. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:323–31. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacol Berl. 1999;146:348–61. doi: 10.1007/pl00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swann AC, Bjork JM, Moeller FG, Dougherty DM. Two models of impulsivity: relationship to personality traits and psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:988–94. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bickel WK, Miller ML, Yi R, Kowal BP, Lindquist DM, Pitcock JA. Behavioral and neuroeconomics of drug addiction: competing neural systems and temporal discounting processes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(Suppl 1):S85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bechara A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: a neurocognitive perspective. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1458–63. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bartra O, McGuire JT, Kable JW. The valuation system: a coordinate-based meta-analysis of BOLD fMRI experiments examining neural correlates of subjective value. Neuroimage. 2013;76:412–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hare TA, Camerer CF, Rangel A. Self-control in decision-making involves modulation of the vmPFC valuation system. Science. 2009;324:646–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1168450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kable JW, Glimcher PW. The neural correlates of subjective value during intertemporal choice. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1625–33. doi: 10.1038/nn2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schacter DL, Addis DR, Hassabis D, Martin VC, Spreng RN, Szpunar KK. The future of memory: remembering, imagining, and the brain. Neuron. 2012;76:677–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crews FT, Boettiger CA. Impulsivity, frontal lobes and risk for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:237–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nigg JT, Wong MM, Martel MM, Jester JM, Puttler LI, Glass JM, et al. Poor response inhibition as a predictor of problem drinking and illicit drug use in adolescents at risk for alcoholism and other substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:468–75. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000199028.76452.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pardini D, White HR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Early adolescent psychopathology as a predictor of alcohol use disorders by young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 1):S38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byrd AL, Loeber R, Pardini DA. Antisocial Behavior, Psychopathic Features and Abnormalities in Reward and Punishment Processing in Youth. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev [Internet] 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0159-6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24357109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Bjork JM, Pardini DA. Who are those “risk-taking adolescents”? Individual differences indevelopmental neuroimaging research. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2015:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castellanos-Ryan N, Rubia K, Conrod PJ. Response inhibition and reward response bias mediate the predictive relationships between impulsivity and sensation seeking and common and unique variance in conduct disorder and substance misuse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:140–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernie G, Peeters M, Gullo MJ, Christiansen P, Cole JC, Sumnall H, et al. Multiple behavioural impulsivity tasks predict prospective alcohol involvement in adolescents. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2013;108:1916–23. doi: 10.1111/add.12283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heitzeg MM, Cope LM, Martz ME, Hardee JE. Neuroimaging Risk Markers for Substance Abuse: Recent Findings on Inhibitory Control and Reward System Functioning. Curr Addict Rep. 2015;2:91–103. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0048-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heatherton TF, Wagner DD. Cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation failure. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:132–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bjork JM, Knutson B, Hommer DW. Incentive-elicited striatal activation in adolescent children of alcoholics. Addiction. 2008;103:1308–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cservenka A, Herting MM, Seghete KLM, Hudson KA, Nagel BJ. High and low sensation seeking adolescents show distinct patterns of brain activity during reward processing. Neuroimage. 2013;66:184–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bjork JM, Chen G, Smith AR, Hommer DW. Incentive-elicited mesolimbic activation and externalizing symptomatology in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:827–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •57.Luijten M, Schellekens AF, Kühn S, Machielse MWJ, Sescousse G. Disruption of Reward Processing in Addiction : An Image-Based Meta-analysis of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3084. This rigorous analysis relied on actual statistical brain map datasets donated from authors of source papers, not just peak activation coordinates reported in published tables. They show that subjects with addictions tend to show reduced effort-mobilization anticipatory activation to rewards, but more hedonic reactions to rewards once delivered. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luijten M, Machielsen MWJ, Veltman DJ, Hester R, de Haan L, Franken IHA. Systematic review of ERP and fMRI studies investigating inhibitory control and error processing in people with substance dependence and behavioural addictions. J Psychiatry Neurosci JPN. 2014;39:149–69. doi: 10.1503/jpn.130052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weafer J, Dzemidzic M, Eiler W, Oberlin BG, Wang Y, Kareken DA. Associations between regional brain physiology and trait impulsivity, motor inhibition, and impaired control over drinking. Psychiatry Res. 2015;233:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •60.Rogers JC, De Brito SA. Cortical and Subcortical Gray Matter Volume in Youths With Conduct Problems: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:64–72. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2423. This review illustrated that many gray matter reductions found in general psychiatric disorders are also found in severe childhood externalizing disorder, as another piece of evidence for common brain mechanisms (or correlates) of psychiatric disturbance. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •61.McTeague LM, Goodkind MS, Etkin A. Transdiagnostic impairment of cognitive control in mental illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;83:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.08.001. An important commentary with supportive evidence that both internalizing and externalizing psychiatric disorders share fundamental cognitive performance decrements, which themselves have been linked to specific neurocircuit functional and structural abnomalities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedman NP, Miyake A. Unity and diversity of executive functions: Individual differences as a window on cognitive structure. Cortex J. Devoted Study. Nerv Syst Behav. 2017;86:186–204. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hugdahl K, Raichle ME, Mitra A, Specht K. On the existence of a generalized non-specific task-dependent network. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:430. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Niendam TA, Laird AR, Ray KL, Dean YM, Glahn DC, Carter CS. Meta-analytic evidence for a superordinate cognitive control network subserving diverse executive functions. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2012;12:241–68. doi: 10.3758/s13415-011-0083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubia K, Alegria AA, Cubillo AI, Smith AB, Brammer MJ, Radua J. Effects of stimulants on brain function in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:616–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Anticevic A, Cole MW, Murray JD, Corlett PR, Wang X-J, Krystal JH. The role of default network deactivation in cognition and disease. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16:584–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •67.Verdejo-Garcia A. Cognitive training for substance use disorders: Neuroscientific mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;68:270–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.018. Helpful review of non-pharmalogical interventions and how they can strengthen top-down control of motivation for substance use, as evidenced by both behavioral outcomes and fMRI signatures. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bickel WK, Yi R, Landes RD, Hill PF, Baxter C. Remember the future: working memory training decreases delay discounting among stimulant addicts. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crowther A, Smoski MJ, Minkel J, Moore T, Gibbs D, Petty C, et al. Resting-state connectivity predictors of response to psychotherapy in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;40:1659–73. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Knutson B, Adams CM, Fong GW, Hommer D. Anticipation of increasing monetary reward selectively recruits nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Verbruggen F, Logan GD. Models of response inhibition in the stop-signal and stop-change paradigms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:647–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Medina KL, Hanson KL, Schweinsburg AD, Cohen-Zion M, Nagel BJ, Tapert SF. Neuropsychological functioning in adolescent marijuana users: subtle deficits detectable after a month of abstinence. J Int Neuropsychol Soc JINS. 2007;13:807–20. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707071032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weintraub S, Bauer PJ, Zelazo PD, Wallner-Allen K, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, et al. I. NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery (CB): introduction and pediatric data. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2013;78:1–15. doi: 10.1111/mono.12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schmitt JE, Eyler LT, Giedd JN, Kremen WS, Kendler KS, Neale MC. Review of twin and family studies on neuroanatomic phenotypes and typical neurodevelopment. Twin Res Hum Genet Off J Int Soc Twin Stud. 2007;10:683–94. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.5.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Neale MC, Cardon LR. Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eaves LJ, Long J, Heath AC. A theory of developmental change in quantitative phenotypes applied to cognitive development. Behav Genet. 1986;16:143–62. doi: 10.1007/BF01065484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]