Abstract

Purpose

To report our initial experience using “whole body and dedicated prostate (WB+P)” MRI as a single exam for the assessment of local recurrence and metastatic disease in patients with suspected recurrent prostate cancer (PCa) after radical prostatectomy (RP).

Materials and Methods

IRB-approved retrospective single-center study. 76 consecutive patients with clinically suspected recurrent PCa following RP underwent combined WB+P-MRI in a single session (10/2014-01/2016). WB+P-MRI scans were evaluated for the detection of disease in the prostate bed, regional nodes and distant sites. Comparison was made to other imaging tests and prostate bed, node and bone biopsies, performed within 90-days.

Results and Conclusions

WB+P-MRI was completed successfully in all patients. Median PSA was 0.36 ng/ml (range:<0.05-56.12). WB+P-MRI identified suspected disease recurrence in 16/76 (21%) of patients (local recurrence in the RP bed in 6/76, nodal metastases in 3/76, osseous metastases in 4/76, and multifocal metastatic disease in 3/76). 43 patients had at least one standard staging scan in addition to WB+P-MRI, with concordance demonstrated between imaging modalities in 36/43(84%). All metastatic lesions detected on other imaging tests were detected on WB+P-MRI. In addition, WB+P-MRI detected osseous metastases in 4 patients with false-negative findings on other imaging tests (including 2 bone scans and 3 CT scans), and excluded osseous disease in 1 patient with a positive 18F-FDG-PET/CT, and subsequent negative bone biopsy.

Whole body and pelvic (WB+P) MRI is feasible in a clinical practice setting, and can provide incremental information when compared to standard imaging in men with suspected PCa recurrence following RP.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, prostatectomy, MRI, recurrence, whole-body

Introduction

Approximately 20-40% of patients develop recurrent disease following radical prostatectomy (RP) which is manifest by a detectable prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (1, 2) that continues to rise. There is international consensus, that following RP, biochemical failure (BCF) may be defined as two consecutive PSA values of >0.2 ng/mL (3). It has been demonstrated that not all patients with BCF develop clinical recurrence; and that for every 100 men treated with RP, approximately 15-30 will develop BCR, and 2-6 of these will die of PCa (4, 5). Several studies have identified a subgroup of patients at high risk of metastases (PSA-doubling time (DT) < 3 months, seminal vesicle invasion (SVI), Gleason score 8-10, or time to PSA recurrence < 3 years (6). In the context of suspected PCa recurrence, the unmet need is disease localization, as recurrences confined to the pelvis may be curable with additional (salvage) therapy to the primary site, whilst disease control can be attainable using targeted treatments in men with oligometastases (7), and extra-pelvic approaches are generally treated systemically. Several parameters, including pathologic stage and grade, the time to the first detectable PSA, the absolute PSA value, and PSA doubling times, have been used to predict or determine whether the recurrence is local or systemic (6). For the identification of a local recurrence following RP, multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) is used (8) with the reported sensitivity and specificity of dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) sequences in combination with T2-weighted to be as high as 88% and 100% respectively (8). 99mTc-bone scintigraphy (bone scan) is the accepted standard for the detection of bone metastases, the most common site of spread, and abdominopelvic CT the standard for nodal and visceral spread (6, 9).

It is well recognized that the diagnostic yield of conventional imaging modalities in this setting is poor (6). In one series, the probability of a positive bone scan in asymptomatic men with a PSA of 10 or less following RP was <1% (10, 11). Similarly, the sensitivity of CT for the detection of lymph node metastases is low. In a series of 132 patients with biochemical failure following RP, only 14% had a positive CT scan for suspected lymph node metastases within 3 years of the PSA rise (12). Given that biochemical recurrence may precede the detection of clinical metastases with conventional imaging by 7-8 years on average (13), and that disease confined to the prostate bed is potentially curable in a proportion of patients (using external beam radiation therapy with or without androgen deprivation therapy), more sensitive tests are required to evaluate the primary site (prostate bed), locoregional and more distant spread. MRI has the capability to detect bone marrow infiltration, an early sign of metastatic involvement, that is not detected by CT and bone scan (6, 14). This increase in sensitivity can enable earlier detection of osseous spread and thereby identify patients who would not benefit from salvage radiotherapy to the prostate bed, sparing ineffective and potentially toxic therapy (15). Little is known regarding the accuracy of whole-body MRI in the detection of occult bone or lymph node metastases in men with biochemical failure following RP (16).

A natural extension to the use of whole-body MRI for the assessment of prostate cancer metastases is to combine it with dedicated multi-parametric prostate MRI to simultaneously assess local and metastatic disease in a single session. Here we report our initial experience using “whole body and dedicated prostate (WB+P)” MRI as a single exam for the assessment of local recurrence and metastatic disease in patients with suspected recurrent PCa after RP.

Materials and Methods

Patient demographics

This IRB-approved retrospective study included 76 consecutive patients that underwent combined WB+P-MRI in a single session for suspected PCa recurrence following RP, with no known local recurrence or metastatic disease at the time of imaging. Patients were referred for WB+P MR imaging by the treating physicians based on elevated PSA, PSA kinetics or patient symptoms suspicious for metastatic disease. Median age was 67 (range: 49-84yrs). All imaging studies were performed between October 2014 and January 2016.

WB+P MRI Imaging

All images were acquired on a 1.5Tesla (1.5T) scanner (MR450, GE Medical Systems,USA). The prostate component consisted of axial T1-weighted imaging, high-resolution axial/coronal/sagittal T2-weighted sequences, diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) with apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps and dynamic contrast-enhanced sequences.

Whole-body MRI consisted of sagittal T1-weighted and T2-weighted fat-saturation sequences of the spine, coronal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) images, coronal T1-weighted sequences, axial T1-weighted fat-saturation LAVA images (producing in/out phase) and axial DWI b50-b900 sequences from the base of the skull to the mid-thighs (supplementary material 1).

Comparative Imaging

Comparator staging imaging studies (99mTc bone scan, CT abdomen/pelvis+-chest, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) and 18F-Sodium Fluoride PET/CT bone scan (NaF-PET/CT bone scan)) performed within 90 days of the WB+P-MRI study, were reviewed for the detection of local prostate cancer recurrence, metastases (osseous and nodal) and significant incidental findings.

Imaging Comparison

All imaging studies had been previously reported in the context of standard clinical practice, by board-certified radiologists. The original reports were used, ie. no image re-interpretation was performed as part of this study. The whole body MRI was read according to a clinical template that contains separate sections for bones, nodes and viscera/soft tissue. A 5-point diagnostic certainty lexicon, which has been in routine clinical use at our institution since 2009, was used to subjectively categorize the level of suspicion (Table 1) (17). The Lexicon was dichotomized, with a score of 1-3 considered negative, and 4-5 positive for the presence of local recurrence or metastatic disease. Two board-certified radiologists then retrospectively compared the WB+P-MRI findings from the original reports to those of the comparator imaging for concordance. Absolute concordance was achieved when the imaging reports were in agreement at the individual patient level for the presence or absence of disease in a lymph node, bone or other site. A discrepancy was classified as major when the WB+P-MRI and comparator imaging study disagreed as to the presence of nodal or distant disease or a clinically significant incidental finding, or minor if related to disease burden or a clinically insignificant incidental finding.

Table 1. 5-point diagnostic certainty scale used in the radiological evaluation of disease.

Descriptions of Lexicon's Qualifying Phrases for Indicating Radiologist's Level of Diagnostic Certainty Specified by Departmental Committee

| Predefined Lexicon Term | Description | Signifies Diagnostic Certainty(%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| “Consistent with” | Is applied if proffered diagnosis is best explanation for finding in view of clinical information provided | >90 |

| “Suspicious for or probable” | Is used if finding is likely to represent but is not pathognomonic for proffered diagnosis | ∼75 |

| “Possible” | Means that finding has some but not all features of one diagnosis, or other features not typically encountered in that diagnosis are also present. | ∼50 |

| “Lass likely” | Is used if proffered diagnosis is believed to have substantially lower likelihood of being correct than other option(s) provided but still remains possible explanation for finding | ∼25 |

| “Unlikely” | Is applied if pioflered diagnosis is believed to have, at best, low likelihood of being actual explanation for finding | < 10 |

Reference Standard

Patient records were evaluated for local disease recurrence and metastatic status, used as the reference standard for all WB+P MRI and comparator imaging included in the study. During this evaluation, the findings of the WB+P MRI, comparator-imaging results, follow-up imaging tests (performed between October 2014-January 2016), and all available clinical and biological data were reviewed, and a bimodal (positive or negative) classification attributed to each patient for the presence of local recurrence, nodal and osseous metastases. In equivocal cases, two board-certified radiologists acted as an expert panel to review all clinical data detailed above.

Results

Study Cohort

The median age was 67 (range: 49-84yrs) and median PSA at the time of imaging was 0.36ng/ml (range: <0.05 - 56.12) (Table 2). Fifty two (68%) were referred with a PSA > 0.2 ng/mL (9), and 24 (32%) for rising values < 0.2 ng/mL and/or a clinical suspicion of disease recurrence based on DRE or decline in performance status. All imaging studies were performed between October 2014 and January 2016 and all 76 patients completed the examination yielding diagnostic quality images with the combined WB+P-MRI acquisition protocol in a single session lasting approximately 90 minutes.

Table 2. Patient Demographics.

| Men post radical prostatectomy (76) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gleason | No. | Median PSA (range); ECE (u/k); SVI (u/k) |

| 6 | 4 | 0.23 (0.06-7.76); 3; 0 |

| 7 | 39 | 0.34 (0.01-56.12); 27; 11 (1) |

| 8 | 13 | 0.35 (<0.05-1.55); 12; 4 (1) |

| 9 | 20 | 0.45 (0.11-8.64); 20; 12 (1) |

| TNM Staging | ||

| TMN | Number | |

| pT2a | 1 | |

| pT2b | 8 | |

| pT2c | 3 | |

| pT3a | 34 | |

| pT3b | 25 | |

| pT4 | 5 | |

| Time between radical prostatectomy and WB+P MRI | ||

| Months | Number | |

| 0-5 | 13 | |

| 6-10 | 10 | |

| 11-15 | 6 | |

| 16-20 | 5 | |

| 21-25 | 4 | |

| 26-30 | 0 | |

| 31-35 | 2 | |

| 36-40 | 1 | |

| 41-45 | 1 | |

| 46-50 | 1 | |

| 51-100 | 17 | |

| 101-200 | 12 | |

| 201-300 | 4 | |

ECE= Extra-capsular extension, SVI= Seminal vesicle invasion, u/k = unknown

Reference standard and WB+P MRI

According to the reference standard, 15 patients (20%) had recurrence (5 patients with local recurrence and 10 patients with recurrent disease outside of the prostate bed). WB+P MRI correctly identified all cases of disease recurrence. 13/15 (87%) of these patients had a PSA >0.2 ng/mL at the time of WB+P MR imaging.

WB+P-MRI findings

Local recurrence in the radical prostatectomy bed was identified on WB+P MRI in 7 (9%) cases (Table 3) of which 3 were biopsy confirmed, 2 were referred for salvage radiation in the absence of histologic confirmation, and 1 was shown to be proliferative cystitis on biopsy (considered false-positive).

Table 3. Identification of suspected local recurrence, osseous and nodal metastases per patient.

| Case | Gleason at RP | PSA (ng/ml) | Local recurrence (Rec), osseous (OM) or nodal metastases (NM) | Biopsy | Additional “Standard imaging” | Discrepancy in imaging techniques? (Patient no.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3+4=7 | 56.12 | Rec, OM, NM | High-grade, predominant pattern 4 recurrence | Bone scan; CT A/P | Yes (Patient 1) |

| 2 | 4+5=9 | 0.25 | Rec | Declined | Bone scan; CT A/P | No |

| 3 | 3+4=7 | 1.76 | Rec | No biopsy performed. Secondary hydronephrosis, ureteric stents inserted; Referred salvage RT and ADT | Nil | n/a |

| 4 | 4+4=8 | <0.05 (ADT) | Rec | No biopsy performed. Referred salvage RT | Nil | n/a |

| 5 | 3+4=7 | 1.17 | Rec | Gleason 3+4=7 recurrence | CT A/P | No |

| 6 | 4+3=7 | 0.1 | Rec | No evidence of carcinoma. Urothelial mucosa with proliferative cystitis | Nil | n/a |

| 7 | 4+4=8 | 1.38 | Rec | Fibromuscular tissue involved by prostatic adenocarcinoma | 18F-FDG-PET/CT | No |

| 8 | 3+4=7 | 0.72 | OM | T11 vertebral body metastatic prostate carcinoma | 18F-FDG-PET/CT | No |

| 9 | 3+4=7 | 0.33 | OM & NM | No biopsy performed | Nil | n/a |

| 10 | 5+4=9 | 0.45 | OM | No biopsy performed | 18NaF-PET/CT bone scan; CT A/P | Yes (Patient 2) |

| 11 | 4+5=9 | 0.22 | NM | No biopsy performed | 18NaF-PET/CT; bone scan | No |

| 12 | 5+4=9 | 1.5 | NM | No biopsy performed | 18F-FDG-PET/CT | No |

| 13 | 3+4=7 | 13.8 | OM | No biopsy performed | Bone scan; CT A/P | Yes (Patient 3) |

| 14 | 4+5=9 | 0.22 | NM | Biopsy attempted – no safe window | Nil | n/a |

| 15 | 4+3=7 | 0.34 | OM, NM | No biopsy performed | Bone scan; CT A/P | Yes (Patient 4) |

| 16 | 4+5=9 | 0.12 | OM | No biopsy performed | Nil | n/a |

Rec= local recurrence; OM= osseous metastases; NM=nodal metastases; ADT= androgen deprivation therapy; CT A/P = CT abdomen and pelvis

Nodal and osseous metastases were identified in 6/76(8%) and 7/76(9%) patients respectively. WB+P-MRI correctly identified nodal metastases in all 6 patients with nodal disease, including 1 patient with a false-negative CT (Patient 1, Table 4, Figures 1-4). WB+P MRI correctly identified the presence of bone metastases in all 7 patients defined as having osseous metastases by the reference standard, including 4 patients with false-negative standard imaging (Patients 1-4, Table 4), and furthermore ruled out bone metastases in 1 patient with false-positive comparator imaging (Patient 5, Table 4).

Table 4. Major Discrepancies per patient, including suspicion scores according to anatomical sites in patients with discrepant findings on different imaging modalities.

| Patient | Stage | Gleason | PSA (ng/mL) | Doubling Time (months) | False NEGATIVE Modality 1 (Lexicon score 0-5) | False NEGATIVE Modality 2 (Lexicon score 0-5) | True POSITIVE Modality (Lexicon score 0-5) | Notes | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pT3b | 7 | 51.12 | 48 | CT Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 0/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

n/a | WB+P MRI Local recurrence: 5/5 Bone: 4/5 Nodes: 4/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

WB+P MRI: 2 cm recurrence prostate bed (dominant pattern 4); pelvic nodal metastases; multiple sub-centimetre osseous metastases | ADT started |

| 2 | pT3b | 9 | 0.45 | 1.9 | CT Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 0/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

NaF PET/CT Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 4/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

WB+P MRI Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 4/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

WB+P MRI: Right pubic bone and inferior pubic rami osseous metastases 18NaF-PET/CT: Right pubic bone and inferior pubic rami osseous metastases |

ADT started |

| 3 | pT3a | 7 | 13.8 | 1.58 | CT Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 0/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

Bone scan Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 4/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

WB+P MRI Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 4/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

WB+P MRI: Solitary 7th rib osseous metastasis | Referral for consideration of hormonal therapy |

| 4 | pT3b | 7 | 0.34 | 28.8 | CT Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 0/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

Bone scan Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 0/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

WB+P MRI Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 4/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

CT: No osseous metastases; left obturator nodal metastatic mass Bone scan: No osseous metastases WB+P MRI: Left obturator nodal metastatic mass; multiple osseous lesions suspicious for metastases |

Biopsy: fragments of bony trabeculae, reactive changes, no evidence of malignancy. Repeat biopsy considered, thought unlikely to yield sufficient tissue for diagnosis. ADT started |

| Patient | Stage | Gleason | PSA (ng/mL) | Doubling Time (months) | False POSITIVE Modality 1 (Lexicon score 0-5) | False POSITIVE Modality 2 (Lexicon score 0-5) | True NEGATIVE Modality (Lexicon score 0-5) | Notes | Management |

| 5 | pT3b | 7 | 0.33 | 1.7 |

18F-FDG-PET/CT Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 4/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

n/a | WB+P MRI Local recurrence: 0/5 Bone: 0/5 Nodes: 0/5 Visceral: 0/5 |

18F-FDG-PET/CT: Focal FDG avid lesion T9 vertebral body WB+P MRI: No osseous metastases |

Biopsy: Bone fragments exhibiting cellular marrow with trilineage hematopoiesis, mild erythroid and megakaryocyti c hyperplasia, no evidence of malignancy |

ADT= androgen deprivation therapy; CT= computed tomography; 18F-FDG-PET/CT= 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography; WB+P MRI: Whole-body and dedicated prostate magnetic resonance imaging

Figure 1. Patient 1. Axial CT slice at the level of the prostate. No local recurrence identified.

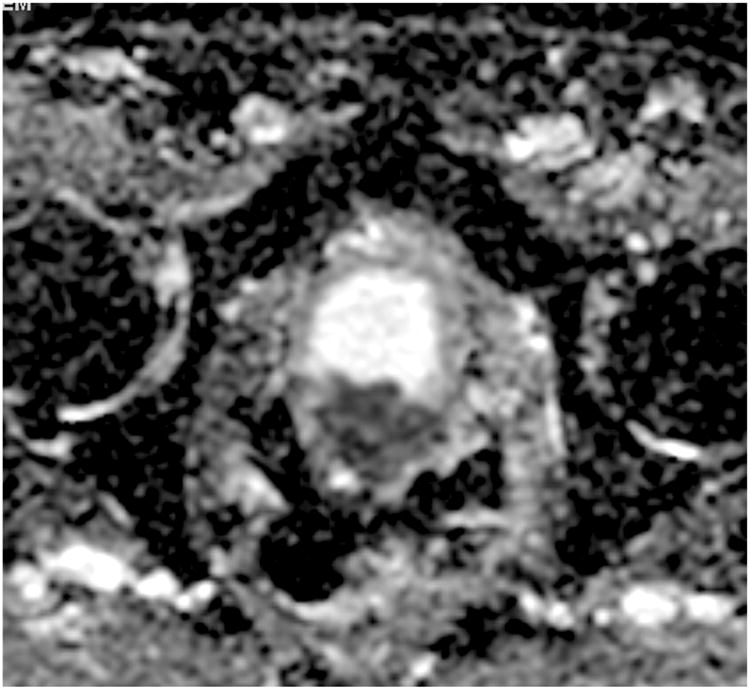

Figure 4. Patient 1. ADC map (axial slice) at the level of the prostate demonstrating focal restricted diffusion within the RP surgical bed (6 o'clock position), highly suspicious for local recurrence.

Comparison of WB+P MRI with Standard Imaging

One or more comparator imaging modalities were available in 43 (57%) of the cohort evaluated of which 36 (84%) gave concordant results (Table 5). Discrepancies were identified in 7 cases: 5 major (Patients 1-5, Table 4) and 2 minor (Table 6). Two independent radiologists reviewed all discrepant findings, and agreed on all 7 cases.

Table 5. Comparison of imaging findings in 43 patients who underwent standard (or accepted) imaging in addition to WB+P MRI.

| Modality | WB+P MRI | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Bone Scan (N=12) | Positive | 1 | 0 |

| Negative | 2 | 9 | |

| CT abdomen/pelvis (N=24) | Positive | 1 | 0 |

| Negative | 3 | 20 | |

| FDG-PET/CT N=8 | Positive | 2 | 1 |

| Negative | 0 | 5 | |

| 18F-NaF-PET/CT bone scan N=7 | Positive | 2 | 0 |

| Negative | 0 | 5 | |

Table 6. Minor Discrepancies per patient.

| Gleason | PSA | WB+P MRI | Conventional imaging | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4+4=8 | 0.08 | Bilateral inguinal lymph node enlargement, likely reactive in etiology | FDG-PET/CT: No lymph node enlargement | Inguinal lymph node biopsy: Reactive changes only |

| 4+5=9 | 0.36 | No osseous metastases | Bone Scan: Diffuse uptake in the radius, unlikely metastases | Biopsy: Paget's disease |

Identification of significant incidental findings

In two patients, with no comparator imaging, WB+P-MRI identified clinically significant incidental findings (new ascites, and pleural-based lung nodules).

Two further significant findings, including a multilocular splenic cyst and a cystic pancreatic mass (likely side-branch intra-ductal papillary mucinous neoplasm) were reported on both WB+P MR and CT imaging. No major discrepancies were identified.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that a single-step WB+P-MRI is feasible in a routine clinical setting, providing clinically relevant information for the assessment of suspected recurrent prostate cancer after RP. Conventional staging approaches involve multi-modality imaging, many of which utilize ionizing radiation and require long examination times. This single-step, non-irradiating strategy may help streamline the staging process by reducing the number of imaging tests and patient hospital visits, without compromising diagnostic performance. Within this cohort, WB+P MRI identified findings suspicious for local recurrence, osseous or nodal metastases in 16/76 (21%) patients. If comparator-imaging tests were performed without WB+P-MR imaging, osseous metastases would have been missed in 2 patients and nodal metastases missed in 1 patient.

Although there is no literature on the use of this approach in the context of recurrent prostate cancer, Pasoglou et al reported on 30 patients with newly diagnosed high-risk prostate cancer who underwent mpMRI and WBMRI (18). They concluded that wbMRI outperforms bone scan+- standard targeted X-rays and abdomino-pelvic CT for discriminating subsets of patients with or without distant spread of cancer at diagnosis. Although a different clinical context, our findings also indicate increased detection rates when comparing WB+P-MRI to conventional imaging modalities. In addition, our comparator imaging included molecular imaging techniques such as 18F-FDG-PET/CT and 18NaF-PET/CT bone imaging, neither of which detected recurrences not identified on WB+P-MRI. The role of molecular imaging in the evaluation of metastatic prostate cancer has not yet been well-defined; however recent studies report that although 18F-FDG-PET/CT is limited in the assessment of low-risk localized disease, 18F-FDG uptake tends to increase in more aggressive recurrent or metastatic prostate cancer (19-21). In our study, absolute concordance was demonstrated between WB+P MRI and 18F-FDG-PET/CT or 18NaF-PET/CT in 7 and 7 patients respectively (Table 5). Jambor et al recently reported similar findings (22). In a prospective evaluation of 27 patients with prostate cancer, at high risk of bone metastases, a similar diagnostic accuracy for the detection of osseous metastases was demonstrated between whole-body MRI (wbMRI) with diffusion imaging and 18NaF-PET/CT (22). Minamimoto et al prospectively evaluated combined 18F-NaF/18F-FDG-PET/CT in comparison to wbMRI for the detection of osseous metastases in 15 patients with suspected or known metastatic prostate cancer. The group report 18F-NaF/18F-FDG-PET/CT superiority in the evaluation of skeletal disease, however suggest larger cohorts are required to confirm their preliminary findings (23).

The diagnostic performance of 18F-Choline-PET/CT in this context remains a matter of debate. Kjolhede et al looked at 58 patients with untreated biochemical recurrence following RP, with a PSA <2ng/mL, and a Gleason score ≥7 or a PSA doubling time of ≤6 months, who underwent 18F-Choline-PET/CT (24). Metastases were reported in 16/58 (28%) patients. The group concluded that 18F-Choline-PET/CT may be valuable for selecting patients with biochemical recurrence following RP for salvage radiotherapy or experimental treatment of oligometastases. The positive predictive value of 18F-Choline-PET/CT compared to secondary lymphadenectomy has been reported in the literature to range between 50-89%, although it has been noted that the populations studied have been small and heterogenous, with further validation required (24). Choline-PET/CT is not currently used as standard of care at our institution; therefore no comparison with WB+P-MRI was possible.

There are several limitations to this preliminary study; including the retrospective design and the subjectivity of the reference standard, with further validation of the WB+P-MRI technique warranted. The ideal reference standard would involve histopathological correlation of all lesions identified on imaging; but this is impractical. The limitations of WB+P-MRI are reflected in our study results. Three patients with clinically significant incidental findings required further organ-specific imaging tests; however importantly there were no false negative findings on WB+P-MRI. The inter- and intra-observer agreement of WB+P-MRI and comparator imaging modalities for the detection of osseous and nodal metastases were not evaluated in this study, yet using standard of care imaging reports prospectively issued by board-certified radiologists makes the study representative of real-life scenarios. Future studies should evaluate the impact of lesions detected on WB+P-MRI (but not on conventional imaging) on patient outcomes.

Conclusion

WB+P-MRI is feasible in a routine clinical setting, providing clinically relevant information in the context of suspected recurrent PCa.

Supplementary Material

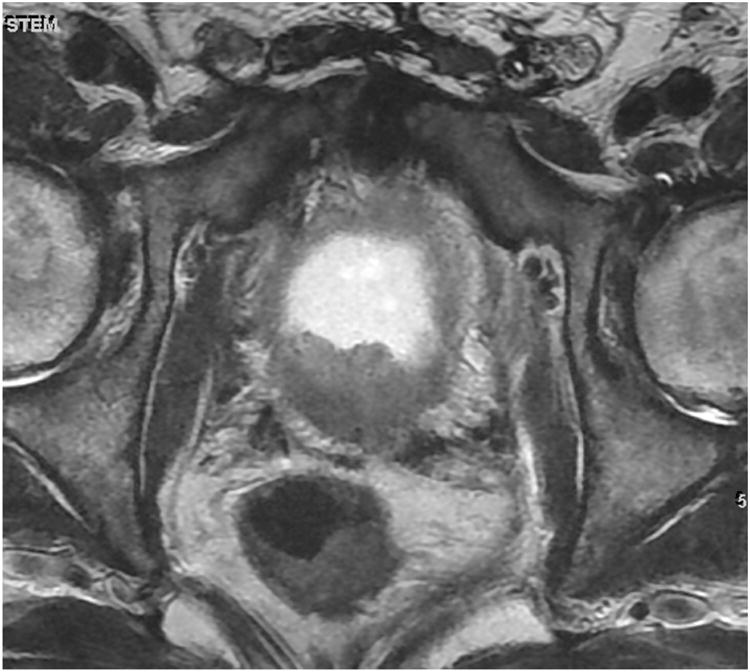

Figure 2. Patient 1. T2-weighted axial slice at the level of the prostate demonstrating focal low signal in the RP surgical bed (6 o'clock position), highly suspicious for local recurrence.

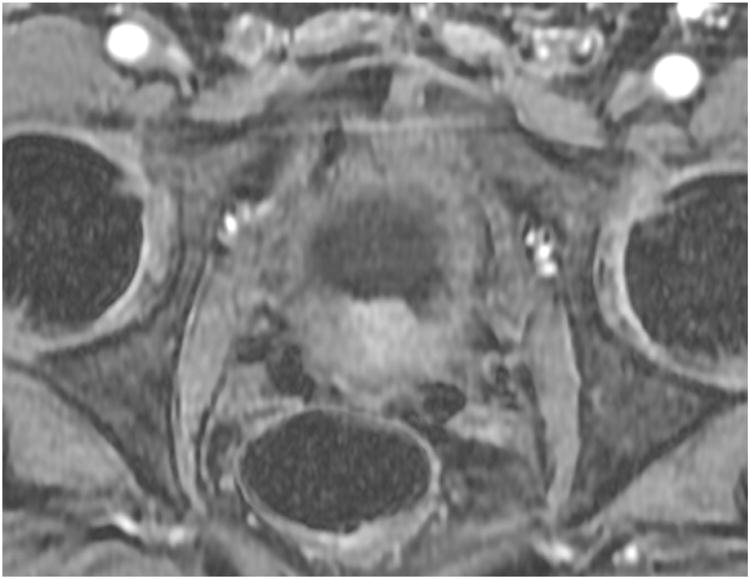

Figure 3. Patient 1. Dynamic contrast-enhanced axial slice at the level of the prostate demonstrating focal enhancement of the RP surgical bed (6 o'clock position), highly suspicious for local recurrence.

Key of Definitions for Abbreviations

- PCa

prostate cancer

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen

- RP

radical prostatectomy

- WB+P MRI

whole-body and dedicated prostate magnetic resonance imaging

- CT

computed tomography

- 18F-FDG-PET/CT

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- 18F-NaF-PET/CT

18F-Sodium Fluoride positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- 18F-Choline-PET/CT

18F-Choline- positron emission tomography/computed tomography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roehl KA, Han M, Ramos CG, Antenor JA, Catalona WJ. Cancer progression and survival rates following anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy in 3,478 consecutive patients: long-term results. J Urol. 2004;172:910–914. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000134888.22332.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, Eisenberger M, Dorey FJ, Walsh PC, et al. Risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2005;294:433–439. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moul JW. Prostate specific antigen only progression of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000;163(6):1632–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, et al. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 1999 May;281(17):1591–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boorjian SA, Thompson RH, Tollefson MK, et al. Long-term risk of clinical progression after biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy: the impact of time from surgery to recurrence. Eur Urol. 2011 Jun;59(6):893–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Briers E, van den Bergh RCN, Bolla M, van Casteren NJ, et al. Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. European Association of Urology. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ost P, Jereczek-Fossa BA, As NV, et al. Progression-free survival following stereotactic body radiotherapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer treatment-naive recurrence: a multi-institutional analysis. Eur Urol. 2016;69:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casciani E, Polettini E, Carmenini, Floriani I, Masselli G, Bertini L, et al. Endorectal and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for detection of local recurrence after radical prostatectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 May;190(5):1187–92. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aus G, Abbou CC, Pacik D, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2001;40:97–101. doi: 10.1159/000049758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cher ML, Bianco FJ, Lam JS, Davis LP, Grignon DJ, Sakr WA, et al. Limited role of radionuclide bone scintigraphy in patients with prostate specific antigen elevations after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 1998 Oct;160(4):1387–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beresford MJ, Gillatt D, Benson RJ, Ajithkumar T. A systematic review of the role of imaging before salvage radiotherapy for post-prostatectomy biochemical recurrence. Clin Oncol. 2010 Feb;22(1):46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane CJ, Amling CL, Johnstone PA, Park N, Lance RS, Thrasher JB, et al. Limited value of bone scintigraphy and computed tomography in assessing biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2003 Mar;61(3):607–11. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rouviere O, Vitry T, Lyonnet D. Imaging of prostate cancer local recurrences: why and how? Eur Radiol. 2010 May;20(5):1254–66. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daffner RH, Lupetin AR, Dash N, Deeb ZL, Sefczek RJ, Schapiro RL. MRI in the detection of malignant infiltration of bone marrow. AJR. 1986;146:353–358. doi: 10.2214/ajr.146.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lecouvet FE, El Mouedden J, Collette L, Coche E, Danse E, Jamar F, et al. Can whole-body magnetic resonance imaging with diffusion-weighted imaging replace Tc 99m bone scanning and computed tomography for single-step detection of metastases in patients with high-risk prostate cancer? Eur Urol. 2012 Jul;62(1):68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eiber M, Holzapfel K, Ganter C, Epple K, Metz S, Geinitz H, et al. Whole-body MRI including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) for patients with recurring prostate cancer: technical feasibility and assessment of lesion conspicuity in DWI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011 May;33(5):1160–70. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wibmer A, Vargas HA, Sosa R, Zheng J, Moskowitz C, Hricak H. Value of a standardized lexicon for reporting levels of diagnostic certainty in prostate MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014 Dec;203(6):W651–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasoglou V, Larbi A, Collette L, Annet L, Jamar F, Machiels JP, et al. One-Step TNM Staging of High-Risk Prostate Cancer using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Toward an Upfront Simplified“all-in-one” ImagingApproach? The Prostate. 2014;74:469–477. doi: 10.1002/pros.22764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jadvar H, Desai B, Conti PS, Conti PS, Dorff TB, Groshen SG, et al. Baseline 18F-FDG PET/CT parameters as imaging biomarkers of overall survival in castrate-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1195–120. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.114116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beauregard JM, Williams SG, Degrado TR, Roselt P, Hicks RJ. Pilot comparison of 18F-fluorocholine and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT with conventional imaging in prostate cancer. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2010;54:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2010.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang CH, Wu HC, Tsai JJ, Shen YY, Changlai SP, Kao A. Detecting metastatic pelvic lymph nodes by 18F-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with prostate-specific antigen relapse after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Urol Int. 2003;70:311–315. doi: 10.1159/000070141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jambor K, Kuisma A, Ramadan S, Huovinen R, Sandell M, Kajander S, et al. Prospective evaluation of planar cone scintigraphy, SPECT, SPECT/CT, 18F-NaF PET/CT and whole body 1.5T MRI, including DWI, for the detection of bone metastases in high risk breast and prostate cancer patients: SKELETA clinical trial. Acta Oncol. 2015 Apr;2:1–9. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1027411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minamimoto R, Loening A, Jamali M, Barkhodari A, Mosci C, Jackson T, et al. Prospective Comparison of 99mTc MDP Scintigraphy, Combined 18F-NaF and 18F-FDG PET/CT and Whole-body MRI in Patients with Breast and Prostate Cancers. J Nucl Med. 2015 Sep 24; doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.162610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kjolhede H, Ahlgren G, Almiquist H, Liedberg F, Lyttkens K, Ohlsson T, et al. (18)F-choline PET/CT for he early detection of metastases in biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy. World J Urol. 2015 Nov;33(11):1749–52. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1547-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.