Abstract

Background

The diagnosis of IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy is often based on anamnesis, and on specific IgE (sIgE) levels and/or Skin Prick Tests (SPT), which have both a good sensitivity but a low specificity, often causing positive results in non-allergic subjects. Thus, oral food challenge is still the gold standard test for diagnosis, though being expensive, time-consuming and possibly at risk for severe allergic reactions.

Aim

The aim of the present study was to perform a systematic review of the studies that have so far analyzed the positive predictive values for sIgE and SPT in the diagnosis of allergy to fresh and baked cow’s milk according to age, and to identify possible cut-offs that may be useful in clinical practice.

Methods

A comprehensive search on Medline via PubMed and Scopus was performed August 2017. Studies were included if they investigated possible sIgE and/or SPT cut-off values for cow’s milk allergy diagnosis in pediatric patients. The quality of the studies was evaluated according to QUADAS-2 criteria.

Results

The search produced 471 results on Scopus, and 2233 on PubMed. Thirty-one papers were included in the review and grouped according to patients’ age, allergen type and cooking degree of the milk used for the oral food challenge.

In children < 2 years, CMA diagnosis seems to be highly likely when sIgE to CM extract are ≥ 5 KUA/L or when SPT with commercial extract are above 6 mm or Prick by Prick (PbP) with fresh cow’s milk are above 8 mm. Any cut-offs are proposed for single cow’s milk proteins and for baked milk allergy in children younger than 2 years. In Children ≥ 2 years of age it is hard to define practical cut-offs for allergy to fresh and baked cow’s milk. Cut-offs identified are heterogeneous.

Conclusions

None of the cut-offs proposed in the literature can be used to definitely confirm cow’s milk allergy diagnosis, either to fresh pasteurized or to baked milk. However, in children < 2 years, cut-offs for specific IgE or SPT seem to be more homogeneous and may be proposed.

Keywords: Children, Cow’s milk allergy, Cut-offs, Predictive value, Skin prick test, α-lactalbumin, β-lactoglobulin, Casein, Positive predictive value, Specificity, Oral food challenge

Background

Cow’s milk (CM) is one of the first causes of food allergy in the first years of life [1] and of food anaphylaxis in pediatric patients [2]. Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) has a prevalence ranging between 1.8 and 7.5% in the first year of life [3]. CMA diagnosis is often based on a compatible clinical history and on the results of specific IgE (sIgE) and/or skin prick tests (SPT). Specific IgEs and SPTs to CM extract or to the single CM allergenic proteins show a good sensitivity but a low specificity. Therefore, sensitization does not correlate well with allergy [4]. If the diagnosis of CMA were only based on sIgE or SPT results, a group of sensitized but non-allergic subjects would uselessly undergo a CM-exclusion diet. Hence, Oral Food Challenge (OFC) is still considered as the gold standard for CMA diagnosis, despite being expensive, time-consuming, and possibly causing allergic reactions which may even result in anaphylaxis.

It has been shown that, the greater the food-sIgE levels and the SPTs wheal size, the higher the chances that patients react during an OFC [4]. This is the reason why some authors have investigated if it is possible to establish a cut-off for sIgEs and SPTs to CM or its proteins, that could predict by itself whether a patient would react to an OFC. Several studies showed that cut-offs may vary with age [5], and previous reviews proposed practical indications to diagnose of food allergy and suggest different diagnostic cut-offs for children, based on age [6–8]. However, cut-offs may vary also because of the cooking degree [9] or the type of allergen used to perform SPTs (commercial extract vs. raw milk). Thus, in the present Systematic Review, we grouped studies according to these three factors.

The aim of this study was to compare, in children with suspected CMA, the levels of sIgEs and the wheal sizes of SPTs for CM or its three main allergenic molecules (α-lactalbumin (αLA), β-lactoglobulin (βLG), and casein) with the Reference Standard (RS) test, OFC, in order to identify any validated cut-off value. We analyzed available data from a methodological point of view and tried to provide practical clinical indications for the diagnosis of CMA in children. At the best of our knowledge, such a classification has never been considered in previous studies [6–8].

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for considering studies for this systematic review

We included studies in which authors looked for a cut-off value for SPTs or sIgEs levels for the diagnosis of CMA in children. In most cases, diagnosis was based on the results of the OFC. Studies were also considered whenever a clear relationship between CM exposure and allergic reaction was highlighted and sIgE or SPTs were carried out.

Studies were excluded if information was not specific enough for CMA, or if the Authors identified the optimal cut-off only (meaning a cut-off based on the best combination between sensibility and specificity), which does not allow to adequately select patients at high risk of reacting to the OFC.

Types of participants

We included children with suspected CMA.

Types of outcome measures

We searched for cut-off values for CMA diagnosis using CM extract, αLA, βLG, casein, for sIgE or SPT, and using fresh milk for PbP.

Search methods for the identification of the studies

On August 2017, we performed a comprehensive search on Medline via PubMed and Scopus, by using the strings “sIgE” or “specific IgE” or “SPT” or “skin prick test” and “milk allergy” or “milk hypersensitivity”. Search was not restricted by publication type or language or study design. If any relevant paper was identified afterwards, we included it as well [3, 10, 11].

We checked reference of all included studies and reviews, for additional references as well.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of the studies

For each string, two authors independently screened titles and abstracts to consider for inclusion all potential identified studies. Full texts were searched as well, to identify studies for inclusion. We resolved disagreements through discussion or, if required, by consultation with a third person. Data extraction from reports was in duplicate and in case of doubts we directly contacted the authors to obtain and confirm data. Studies were all widely discussed in detail and evaluated by the authors in a standardized and independent manner.

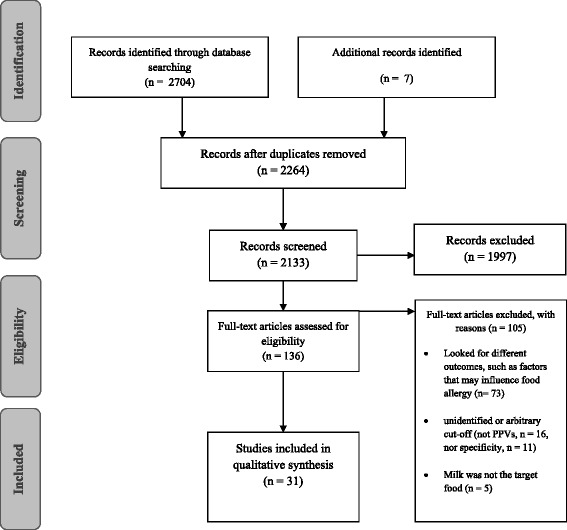

We recorded the selection process to complete a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the search run to obtain the studies included in the present review

Methodological quality evaluation of the included studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated according to criteria proposed by QUADAS-2 [12]. In order to establish the risk of bias, papers were independently revised by at least two authors, and any divergence was resolved by discussion and agreement among all reviewers.

Results

The search identified 2233 articles of potential interest on Medline, and 471 articles on SCOPUS. After the selection process, a total of 31 articles were included in this systematic review. Of these, 22 referred to the cut-off for sIgE and 13 for SPT cut-offs (4 proposed cut-offs for both) (Fig. 1). These studies are presented separately below, grouping them based on:

sIgEs levels or SPT wheal size;

- patients’ age, enrolling children:

- < 2 years;

- >2 years;

- any age;

- the cooking degree of CM administered during the OFC:

- CM: fresh pasteurized CM (or CM formula in children <12 months of age);

- baked milk: extensively heated CM (> 100 °C or 212 °F for several minutes).

Among the studies dealing with sIgE and SPT cut-offs, 11/22 (50%) and 7/13 (53.8%), respectively were prospective [9, 13–26], while the remaining were either retrospective or with unspecified design.

Most studies analyzed the role of sIgE and SPTs for CM in patients allergic to fresh pasteurized milk [4, 5, 13–21, 27–39]. Five studies evaluated sIgE and SPTs in patients allergic to baked milk [9, 24–26, 40].

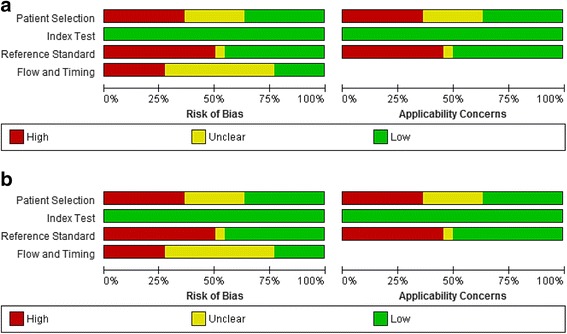

According to QUADAS-2 evaluation: a) for sIgE studies: patients’ selection was considered at low risk for both bias and applicability in 8 studies, index test choice was at low risk for bias and applicability in all the studies, reference standard in 10 and flow and timing only in 5 (Fig. 2a; b) for SPT studies all articles but three [23, 26, 39] were judged to be at high risk of bias and applicability as for patients’ selection (Fig. 2b).

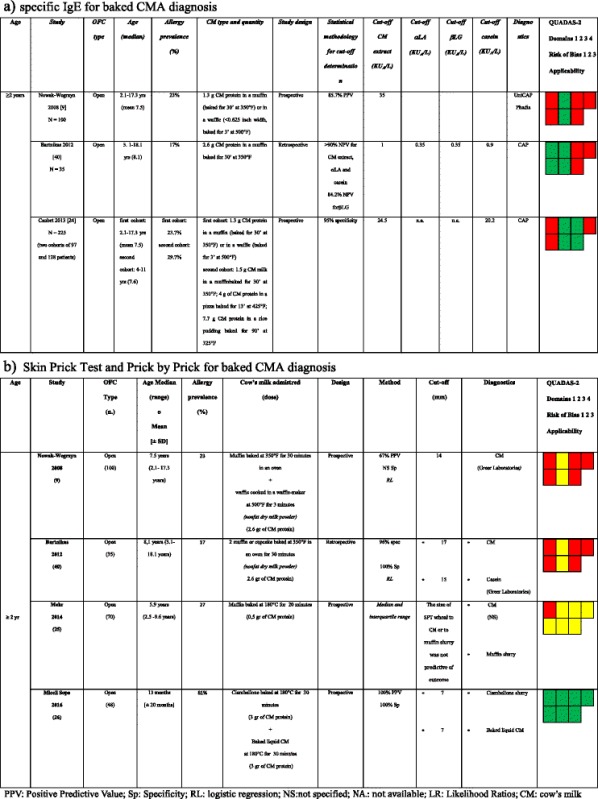

Fig. 2.

Methodological quality of the articles included in the present revision according to the QUADAS-2 tool [12]. a Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors’ judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included specific-IgE studies Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014. b Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors’ judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included SPT studies. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014

Predictive value of sIgE and SPT for the diagnosis of fresh pasteurized CMA

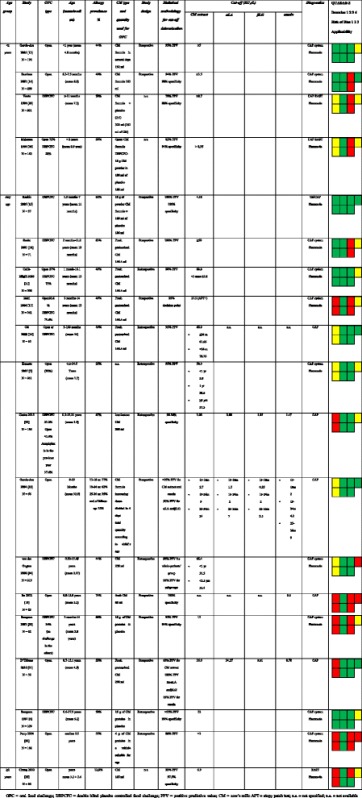

Table 1 shows the 19 studies evaluating the diagnostic efficacy of CM sIgE; five of them assessed the role of sIgE for αLA, βLG, and casein as well. Studies differed in prevalence of any type of allergic disease and atopic dermatitis, statistical analysis, type of chosen cut-offs, and methodology. These factors might explain the large variability of the proposed cut-offs, which vary from 0.35 to 88.8 KUA/L.

Table 1.

Studies and cut-offs suggested for fresh pasteurized CMA diagnosis using sIgE for CM extract, α-lactalbumin (αLA), β-lactoglobulin (βLG), and casein stratified by study design and ordered by age group [4, 5, 13–21, 29–36]

As for sIgE against CM, considering those studies including only children younger than 2 years, two prospective studies with a good QUADAS-2 evaluation and with significant patients’ numbers showed quite similar cut-offs for a 95% positive predictive value (PPV) (≥3.5 KUA/L [14] and ≥5 KUA/L [13]), even if the second cut-off was proposed in a study with an important risk of bias for its “reference standard” domain. Considering those studies including children of any age, very different values have been proposed even with similar statistical methods. For example, cut-offs with a 100% PPV varied between 4.18 KUA/L [15] and 50 KUA/L [16]. Four papers [18, 19, 21, 33] proposed sIgE cut-offs for the main allergenic CM components. These studies were conducted in children of any age and found extremely heterogeneous cut-off values, distributed in a very wide range without a clear explanation (αLA: 1.5–34 KUA/L; βLG: 0.35–9.91 KUA/L; casein: 0.78–6.6 KUA/L) [18, 19, 21]. The only study enrolling children aged more than 2 years had a low methodologic quality and showed a 6.9 KUA/L cut-off for CM extract with a 97.5% specificity [35].

Four studies evaluated PPV of SPTs through commercial extracts (Table 2a). Studies differ in allergy prevalence, statistical analysis, type of cut-off, and type of allergen used for SPTs. All these factors may help explain the variability of the cut-offs proposed by the Authors, ranging from 4.3 to 20 mm. In the paper by Calvani et al. [27], the Authors suggest that the positivity for all the three milk proteins has a higher diagnostic value (PPV > 90%) rather than the single possible cut-offs for each one of them, separately considered; a similar hypothesis has been later proposed by two more studies, even though with a lower PPV (86.7% [28] and 74% [23]).

Table 2.

Studies and suggested cut-offs for fresh cow’s milk allergy diagnosis using alpha-lactoalbumin, beta-lactoglobulin, casein, cow’s milk SPTs stratified by the type of allergen used to perform SPTs, design, and age (<2 years and ≥2 years) [14, 17, 22, 23, 27, 28, 37–39]

Two papers evaluated a possible cut-off using PbP for CMA in children younger than 2 years [14, 37] and the results are quite similar: 8 and 9.7 mm, with a PPV of 92% and 95%, respectively. Six studies, conducted on children but with no respect to age groups, reported results that ranged between 9.3 mm and 15.7 mm (Table 2b) [17, 23, 27, 28, 37, 38].

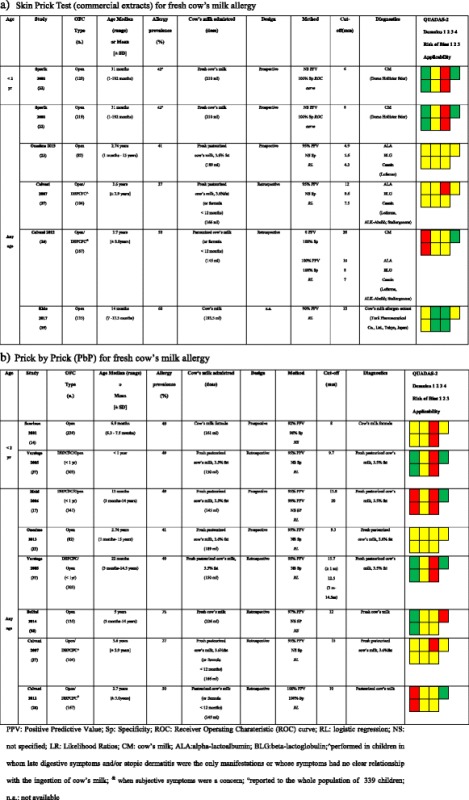

Predictive value of sIgE and SPT for the diagnosis of baked CMA

Three studies analyzed the diagnostic efficacy of sIgE against CM or its allergenic proteins in patients allergic to baked milk (Table 3a) [9, 24, 40]. All these studies enrolled children aged more than 2 years. The cut-offs highlighted in these papers cannot be compared due to the different statistical methods used by the Authors: e.g. for sIgEs against CM extract, Nowak-Wegrzyn proposed a cut-off of 35 KUA/L with a 85.7% PPV, whereas Caubet of 24.5 KUA/L with a 95% specificity.

Table 3.

Studies and cut-offs suggested for baked CMA diagnosis using CM extract, α-lactalbumin (αLA), β-lactoglobulin (βLG), and casein for sIgE or SPT and using fresh milk for PbP. OFC = oral food challenge; PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value; CM = cow’s milk; n.a. = not available [9, 40, 24]

Three studies investigated a possible cut-off for SPTs using milk extracts or its proteins to diagnose allergy to milk that was extensively cooked in a grain matrix (muffins). Only two of these studies reached a conclusion (Table 3b) [5, 20, 36]. The two identified cut-offs, using CM extract, are much higher if compared with those for fresh pasteurized milk (14 and 17 mm, respectively), but differ greatly in terms of predictability (a 67% PPV in one study and a 96% specificity in the other one). Moreover, these studies showed that wheals of 5 mm and 7 mm, respectively, for CM extracts have a 100% negative predictive value (NPV). Two studies [25, 26] evaluated the predictive value of PbP with muffin or with Italian cake (named ciambellone) containing baked CM within a wheat matrix. In the first study, the size of the SPT wheal to CM or to muffin slurry was not predictive of outcome. In the second, OFCs were always failed if PbP mean wheal diameter using baked cake or baked liquid cow’s milk were >7 mm (100% PPV). The same study showed that every negative PbP corresponded to a passed OFC for baked cake in CMA patients [26].

Discussion

Over the last years, several studies have looked for cut-offs for sIgE or SPTs able to predict CMA without the need to perform an OFC.

To find more homogeneous cut-offs, we grouped the studies according to:

patients’ age. Most of the studies on fresh pasteurized CMA diagnosis included children aged from few months to several years. Only the paper from Chung [35] enrolled children aged more than 1 year (mean age 3.1 ± 1.4). On the contrary, all the studies on baked CMA enrolled children aged more than 2 years. Therefore, we divided the studies into three groups: a) those enrolling children aged less than 2 years (< 2 years group); b) those enrolling children aged more than 2 years (> 2 years age group); c) and those enrolling children of any age group;

type of allergen. Several studies showed that SPT mean wheal diameter is usually different between commercial extracts and fresh food [27, 41];

cooking degree of the milk. It is well known that CM proteins are modified by exposure to high temperatures, which not only modify the conformational epitopes, but partly the sequential ones as well. Heating is one of the most common technological treatment applied to milk processing and it may have different effects on the binding of IgE to proteins. Mild treatments are not sufficient to reduce the allergenicity of milk as it has been shown for pasteurized milk, which is able to elicit allergic responses in milk allergic patients [42]. On the other hand, when milk is exposed to higher temperatures and for a longer time, its allergenicity is reduced. Moreover, when milk is cooked in a grain matrix for a long time, as it happens in baked products, its proteins are modified both by heat and by chemical reactions occurring between the matrix fats and sugars, and are therefore less likely to be recognized by the immune system of the allergic patient (the so-called “matrix effect”) [43].

Limitations

Grouping studies has reduced the variability of the cut-offs proposed, but not substantially. On the other hand, many other factors may influence the cut-offs, both for sIgE and for SPT, such as:

different statistical methods (e.g. PPV or specificity). Two different kinds of cut-offs values are proposed in literature, both for SPT and for sIgEs: those based on a high PPV (95% PPV) and those based on a high specificity (95% specificity). The first ones, being based on the predictive value, depend on several factors, above all on the prevalence of allergy in the studied population, background history, sex, etc., and are applicable in allergy centers where it is assumed that the diagnostic criteria and the prevalence of food allergy are similar to those found in those studies providing the values. On the contrary, cut-off values based on 95% specificity do not change with the prevalence of the disease in the population and give us the possibility to better select children to test with OFC, given the high risk of a positive challenge. These two kinds of cut-off values may produce different results even in the same study population [44].

variations in the chosen level of predictive value in different studies (e.g. 90% vs. 95%) may substantially change the proposed cut-offs.

methodological quality (e.g. studies with a small number of DBPCFC performed, with high risk of bias or including a small number of patients); d) differences in patients’ selection or in the definition of a positive OFC (e.g. one study [14] considers as positive an OFC in which late reactions appear at home, such as atopic dermatitis or others). Moreover, several variables may affect the wheal size of positive SPT, such as type of devices or test technique, composition and potency of commercial extracts, and the “histamine skin reactivity” [45, 46].

Finally, wheal dimensions vary widely, depending on the individual characteristics, geographical setting and may change over time [47].

Practical clinical indications

Given the large variability of the proposed cut-offs, it is hard to propose practical clinical indications. However:

in children < 2 years, proposed cut-offs seem to be homogeneous enough. The studies with the highest methodological quality suggest a 95% PPV cut-off for sIgEs of 5 KUA/L [13] and a 98% specificity cut-off for PbP with fresh milk of 8 mm [14]. As for SPT with commercial extract, the only included study, which is prospective but with QUADAS-2 bias, proposed a 100% specificity SPT cut-off of 6 mm [22]. None of the studies proposed cut-offs for single CM protein SPT and one study only did for sIgE [18]. None of the studies for baked milk allergy enrolled children aged less than 2 years;

in children ≥2 years of age, it is hard to define practical cut-offs for CMA. The cut-offs proposed for SPT with commercial extracts or fresh milk are heterogeneous, probably because most of the studies included children of any age and with no differentiation in age groups. A large variability in cut-offs has been recorded for single CM proteins as well, especially for sIgE levels, even when selecting methodologically valid studies using the same statistical methods. For example, two DBPCFC prospective studies [15, 16], with similar allergy prevalence (respectively 62% and 63%), and similar population age (respectively 1.5 months −7 years, mean 11 months; and 11 months – 11.2 years, mean 13 months), proposed sIgE cut off values with a 100% PPV for 4.18 and >50 KUA/L, respectively. CM type and quantity used for OFC or other known factors listed before (e.g. methodological quality) or unknown issues could explain these differences. As for baked milk allergy, there are only a few studies investigating cut off values for both specific IgE and SPT, and they showed a low methodological value. However, using CM extract, cut-offs seem to be higher if compared with those for fresh pasteurized milk. A single prospective study with a low risk of bias and applicability showed a 100% PPV for wheal diameter cut-off value of 7 mm when fresh CMA patients were pricked with baked cake for predicting baked CMA [26].

Conclusions

No proposed cut-off can be used to definitely confirm a diagnosis of CMA, either with fresh pasteurized or with baked milk. Cut-offs may be affected by many factors, and especially PPV cut-offs may be considered as useful only in the same allergy unit in which they were detected, and may be extrapolated to other centers only if they have similar allergy prevalence. However, with these limits, in children < 2 years, when sIgE against CM are above 5 KUA/L or when SPT with commercial extract are above 6 mm or PbP with CM are above 8 mm, the real need for a diagnostic confirmation of CMA through an OFC should be carefully evaluated.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no sources of funding.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- CM

Cow’s milk

- CMA

Cow’s milk allergy

- DBPCFC

Double blind placebo controlled food challenge

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- OFC

Oral food challenge

- PbP

Prick by Prick

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- sIgE

Specific IgE

- SPT

Skin prick test

- αLA

α-lactalbumin

- βLG

β-lactoglobulin

Authors’ contributions

All the authors participated in the search and the discussion of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sampson HA. Food allergy, part 1: immunopathogenesis and clinicaldisorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:717–728. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calvani M, Cardinale F, Martelli A, Muraro A, Pucci N, Savino F, Italian Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology Anaphylaxis’ Study Group et al. Risk factors for severe pediatric food anaphylaxis in Italy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:813–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luyt D, Ball H, Makwana N, Green MR, Bravin K, Nasser SM, et al. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:642–672. doi: 10.1111/cea.12302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sampson HA, Ho DG. Relationship between food-specific IgE concentrations and the risk of positive food challenges in children and adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:444–451. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(97)70133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komata T, Söderström L, Borres MP, Tachimoto H, Ebisawa M. The predictive relationship of food-specific serum IgE concentrations to challenge outcomes for egg and milk varies by patient age. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1272–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Assa'ad AH, Bahna SL, Bock SA, Sicherer SH, Teuber SS, Work Group report: oral food challenge testing Adverse reactions to food committee of American academy of allergy, asthma & immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(6 Suppl):S365–S383. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Järvinen KM, Sicherer SH. Diagnostic oral food challenges: procedures and biomarkers. J Immunol Methods. 2012;383(1–2):30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sampson HA, Aceves S, Bock SA, James J, Jones S, Lang D, Nadeau K, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Oppenheimer J, Perry TT, Randolph C, Sicherer SH, Simon RA, Vickery BP, Wood R, Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. Bernstein D, Blessing-Moore J, Khan D, Lang D, Nicklas R, Oppenheimer J, Portnoy J, Randolph C, Schuller D, Spector S, Tilles SA, Wallace D, Practice Parameter Workgroup. Sampson HA, Aceves S, Bock SA, James J, Jones S, Lang D, Nadeau K, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Oppenheimer J, Perry TT, Randolph C, Sicherer SH, Simon RA, Vickery BP, Wood R. Food allergy: a practice parameter update-2014. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1016–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Bloom KA, Sicherer SH, Shreffler WG, Noone S, Wanich N, et al. Tolerance to extensively heated milk in children with cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochwallner H, Schulmeister U, Swoboda I, Spitzauer S, Valenta R. Cow’s milk allergy: From allergens to new forms of diagnosis, therapy and prevention. Methods. 2014;66:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, Dias JA, Heuschkel R, Husby S, European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow's-milk protein allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Committee practical guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:221–229. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31825c9482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Ara C, Boyano-Martínez T, Díaz-Pena JM, Martín-Muñoz F, Reche-Frutos M, Martín-Esteban M. Specific IgE levels in the diagnosis of immediate hypersensitivity to cow’s milk protein in the infant. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:185–190. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.111592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saarinen KM, Suomalainen H, Savilahti E. Diagnostic value of skin-prick and patch tests and serum eosinophil cationic protein and cow’s milk-specific IgE in infants with cow’s milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:423–429. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keskin O, Tuncer A, Adalioglu G, Sekerel BE, Sackesen C, Kalayci O. Evaluation of the utility of atopy patch testing, skin prick testing, and total and specific IgE assays in the diagnosis of cow’s milk allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94:553–560. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roehr CC, Reibel S, Ziegert M, Sommerfeld C, Wahn U, Niggemann B. Atopy patch tests, together with determination of specific IgE levels, reduce the need of oral food challenge in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:548–553. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehl A, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Staden U, Verstege A, Wahn U, Beyer K, et al. The atopy patch test in the diagnostic workup of suspected food-related symptoms in children. J Allergy ClinImmunol. 2006;118:923–929. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Ara MC, Boyano-Martínez MT, Díaz-Pena JM, Martín-Muñoz MF, Martín-Esteban M. Cow’s milk-specific immunoglobulin E levels as predictor of clinical reactivity in the follow-up of the cow’s milk allergy infants. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:866–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito K, Futamura M, Movérare R, Tanaka A, Kawabe T, Sakamoto T, et al. The usefulness of casein-specific IgE and IgG4 antibodies in cow’s milk allergic children. Clin Mol Allergy. 2012;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampson HA. Utility of food-specific IgE concentration in predicting symptomatic food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:891–896. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Urbano LE, Pellegrino K, Artesani MC, Donnanno S, Luciano R, Riccardi C, et al. Performance of a component-based allergen-microarray in the diagnosis of cow’s milk and hen’s egg allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:1561–1570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sporik R, Hill DJ, Hosking CS. Specificity of allergen skin testing in predicting positive open challenge to milk, egg and peanut in children. ClinExp Allergy. 2000;30:1540–1546. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onesimo R, Monaco S, Greco M, Caffarelli C, Calvani M, Tripodi S, et al. Predictive value of MP4 (Milk Prick Four), a panel of skin prick test for the diagnosis of pediatric immediate cow's milk allergy. Eur Ann Allergy ClinImmunol. 2013;45:201–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caubet JC, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Moshier E, Godbold J, Wang J, Sampson HA. Utility of casein-specific IgE levels in predicting reactivity to baked milk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:222–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehr S, Turner PJ, Joshi P, Wong M, Campbell DE. Safety and clinical predictors of reacting to extensively heated cow’s milk challenge in cow’s milk-allergic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miceli Sopo S, Greco M, Monaco S, Bianchi A, Cuomo B, Liotti L, Iacono ID. Matrix effect on baked milk tolerance in children with IgE cow milk allergy. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2016;44(6):517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calvani M, Alessandri C, Frediani T, Lucarelli S, Miceli Sopo S, Panetta V, et al. Correlation between skin prick test using commercial extract of cow's milk protein and raw cow milk and food challenges. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18:583–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calvani M, Berti I, Fiocchi A, Galli E, Giorgio V, Martelli A, et al. Oral food challenge: safety, adherence to guidelines and predictive value of skin prick testing. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:755–761. doi: 10.1111/pai.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanto T, Juntunen-Backman K, Kalimo K, Klemola T, Koivikko A, Koskinen P, et al. The patch test, skin prick test, and serum milk-specific IgE as diagnostic tools in cow’s milk allergy in infants. Allergy. 1999;14:837–842. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majamaa H, Moisio P, Holm K, Kautiainen H, Turjanmaa K. Cow’s milk allergy: diagnostic accuracy of skin prick and patch tests and specific IgE. Allergy. 1999;54:346–351. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Celik-Bilgili S, Mehl A, Verstege A, Staden U, Nocon M, Beyer K, et al. The predictive value of specific immunoglobulin E levels in serum for the outcome of oral challenges. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:268–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ott H, Baron JM, Heise R, Ocklenburg C, Stanzel S, Merk HF, et al. Clinical usefulness of microarray-based IgE detection in children with suspected food allergy. Allergy. 2008;63:1521–1528. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castro AP, Pastorino AC, Gushken AK, Kokron CM, Filho UD, Jacob CM. Establishing a cut-off for the serum levels of specific IgE to milk and its components for cow’s milk allergy: Results from a specific population. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2015;43:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Gugten AC, den Otter M, Meijer Y, Pasmans SG, Knulst AC, Hoekstra MO. Usefulness of specific IgE levels in predicting cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:531–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung BY, Kim HO, Park CW, Lee CH. Diagnostic Usefulness of the Serum-Specific IgE, the Skin Prick Test and the Atopy Patch Test Compared with That of the Oral Food Challenge Test. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:404–411. doi: 10.5021/ad.2010.22.4.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perry TT, Matsui EC, Kay Conover-Walker M, Wood RA. The relationship of allergen-specific IgE levels and oral food challenge outcome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verstege A, Mehl A, Rolinck-Werningaus C, Staden U, Nocon M, Beyer K, Staden U, Nocon M, Beyer K, et al. The predictive value of the skin prick test weal size for the outcome of oral food challenges. ClinExp Allergy. 2005;35:1220–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.2324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellini F, Ricci G, Remondini D, Pession A. Cow's milk allergy (CMA) in children: identification of allergologic testspredictive of food allergy. Eur Ann Allergy ClinImmunol. 2014;46:100–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kido J, Hirata M, Ueno H, Nishi N, Mochinaga M, Ueno Y, Yanai M, Johno M, Matsumoto T. Evaluation of the skin-prick test for predicting the outgrowth of cow's milk allergy. Allergy Rhinol (Providence) 2016;7(3):139–143. doi: 10.2500/ar.2016.7.0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartnikas LM, Sheehan WJ, Hoffmann EB, Permaul P, Dioun AF, Friedlander J, et al. Predicting food challenge outcomes for baked milk: role of specific IgE and skin prick testing. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:309–313. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim TE, Park SW, Noh G, Lee S. Comparison of skin prick test results between crude allergen extracts from foods and commercial allergen extracts in atopic dermatitis by double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge for milk, egg, and soybean. Yonsei Med J. 2002;43(5):613–620. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2002.43.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Host A, Samuelsson EG. Allergic reactions to raw, pasteurized, and homogenized pasteurized cow milk -a comparison- a double-blind placebo-controlled study in milk allergic children. Allergy. 1988;43:13–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1988.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas K, Herouet-Guicheney C, Ladics G, Bannon G, Cockburn A, Crevel R, et al. Evaluating the effect of food processing on the potential human allergenicity of novel proteins: international workshop report. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1116–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Sterne K. Essential Medical Statistics. 2. Melbourne: Blackwell Science Ltd.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Proficiency testing: Skin prick test. 2013 https://aaaai.confex.com/aaaai/2013/webprogramhandouts/Session1315.html. Accessed 25 Jan 2013.

- 46.Bernstein IL, Li JT, Bernstein DI, Hamilton R, Spector SL, Tan R, et al. Allergy diagnostic testing: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(3 Suppl 3):S1–148. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Dreborg S. Allergen skin prick test should be adjusted by the histamine reactivity. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2015;166(1):77–80. doi: 10.1159/000371848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.