ABSTRACT

Lignocellulosic biomass is an attractive low-cost feedstock for bioethanol production. During bioethanol production, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the common used starter, faces several environmental stresses such as aldehydes, glucose, ethanol, high temperature, acid, alkaline and osmotic pressure. The aim of this study was to construct a genetic recombinant S. cerevisiae starter with high tolerance against various environmental stresses. Trehalose-6-phosphate synthase gene (tps1) and aldehyde reductase gene (ari1) were co-overexpressed in nth1 (coded for neutral trehalase gene, trehalose degrading enzyme) deleted S. cerevisiae. The engineered strain exhibited ethanol tolerance up to 14% of ethanol, while the growth of wild strain was inhibited by 6% of ethanol. Compared with the wild strain, the engineered strain showed greater ethanol yield under high stress condition induced by combining 30% glucose, 30 mM furfural and 30 mM 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF).

KEYWORDS: Aldehyde reductase, ethanol production, neutral trehalase, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Trehalose, Trehalose-6-phosphate synthase

Introduction

Lignocellulosic biomass and agricultural residues are most widely used for bioethanol production. Acid hydrolysis is commonly used as a pretreatment to convert lignocellulosic materials into sugars. During acid hydrolysis of lignocellulosic materials, furfural and HMF are generated by dehydration of pentoses and hexoses, respectively, and both furfural and HMF are representative aldehyde inhibitors.1,2 Aldehydes are toxic to yeasts in inhibition of cell growth3-5 and production of ethanol.6 Beside aldehydes inhibitors, yeasts need to overcome various stresses during converting sugars to ethanol, such as acid left from pretreatment, high osmotic pressure of hydrolysates, high ethanol concentrations at the last stage of fermentation, high temperature for accelerating fermentation, and process interruptions. Survival under various stress conditions is an important feature required for yeast to produce ethanol efficiently.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been wildly used as a starter in bioconversion of ethanol. It has natural ability to convert furfural and HMF to furfuryl alcohol7,8 and 2,5-bis-hydroxymethylfuran,9 respectively. Reduction of aldehydes, mainly furfural and HMF in the lignocellulosic substrate, helps to improve the cell growth and subsequent ethanol production.10-12 Many researches demonstrated that overexpression of the aldehyde dehydrogenase/reductase genes (ari1, ald6 and adh6) in S. cerevisiae not only could eliminate the toxicity of aldehydes but also improve tolerability.12-15

Trehalose, a non-reducing disaccharide, works as an energy source in yeasts, bacteria, fungi, invertebrates, insects and plants.16,17 Many research demonstrated that the higher trehalose accumulated in the yeast cell the higher tolerance against various environmental stresses, for instance ethanol stress,18 heat stress,19 saline stress,20 and various other environmental stresses.21,22 In S. cerevisiae, concentration of trehalose is regulated by synthesis enzymes and hydrolysis enzymes. Enzymes involved in trehalose synthesis including trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS, encoded by tps1), trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase (TPP, encoded by tps2) and 2 other proteins, TSL1 and TPS3.23 On the other hand, trehalose is hydrolyzed into glucose by neutral trehalases (encoded by nth1 and nth2) and acid trehalase (encoded by ath1).24

In our previous study,25 an engineering S. cerevisiae (named as SCTΔN) was constructed by overexpression of tps1 and disruption of nth1. The engineered strain showed greater ethanol yield than the wild type strain when the medium contained more than 15% glucose (under glucose stress). In the present study, aldehyde reductase gene (ari1) was further overexpressed in SCTΔN and the tolerance of present strain was great improved. This study is the first to report the co-expression of tps1 gene and ari1 gene in S. cerevisiae to protect cells against not only environmental stresses but aldehyde inhibitors as well.

Results

Expression of trehalose-6-phosphate synthase and aldehyde reductase

In our previous study25 SCT (S. cerevisiae with tps1 gene overexpression) and SCTΔN (nth1 gene of SCT was disrupted) were constructed from S. cerevisiae BCRC 21685 (SC). Concentration of intracellular trehalose was in the order of SCTΔN>SCT>SC. Compared to SC, SCTΔN showed greater viability and ethanol productivity under 15% of ethanol and 10% of glucose, respectively.

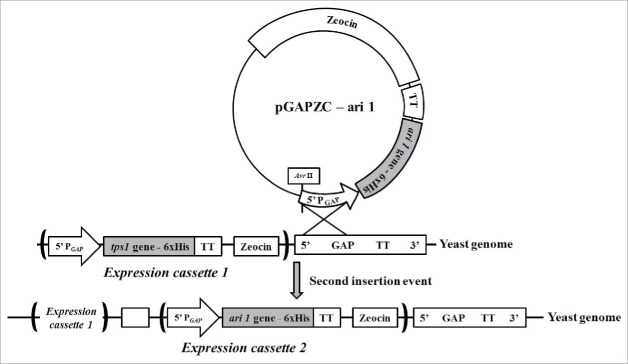

To create a starter for production of bioethanol, ari1 DNA (encode for aldehyde reductase gene) of SC was inserted in the sense orientation, downstream of the GAP promoter of pGAPZαC to create pGAPZC-ari1. Both SCT and SCTΔN were served as the host for homologous recombination of pGAPZC-ari1 in their gnomic DNA, and PCR and western blot were applied to confirm the transformates, named as SCTA and SCTAΔN, respectively.

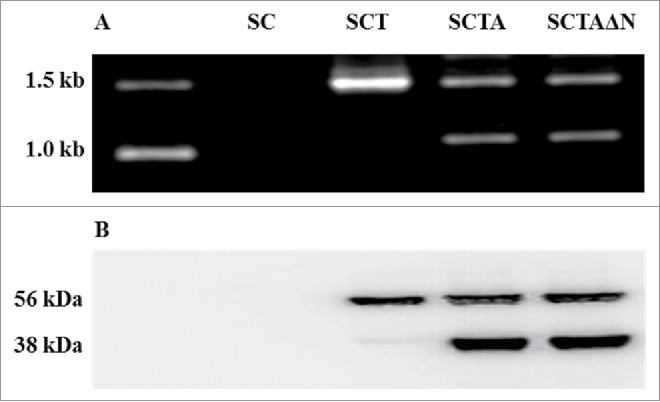

Fig. 2 showed the DNA electrophoresis of PCR products for verification of recombinant ari1 DNA. As shown in the Fig. 2A, SCT contained a DNA fragment about 1.5 kb (tps1 gene); while two DNA fragments, about 1.5 kb (tps1 gene) and 1.0 kb (ari1 gene), presented in SCTA and SCTAΔN. Wild strain (SC) did not generate any PCR product. Results of western blot (Fig. 2B) showed one protein band about 56 kDa (trehalose-6-phasphate synthase) in SCT, and 2 protein bands about 56 kDa (trehalose-6-phasphate synthase) and 38 kDa (aldehyde reductase) in SCTA and SCTAΔN. Again, no protein band appeared in SC. Results of PCR and western blot approved successful recombination and expression of ari1 in SCTA and SCTAΔN.

Figure 2.

(A) PCR confirmation of the recombinant expression vectors pGAPZC-tps1 and pGAPZC-ari1 in SC, SCT, SCTA and SCTAΔN. (B) overexpression of TPS and ARI in SC, SCT, SCTA and SCTAΔN.

Trehalose concentration under ethanol stress conditions

In our previous study, we found that overexpression of tps1 gene could increase the intracellular trehalose content in yeast cells.25 In the present study, the effect of ari1 gene overexpression on the intracellular trehalose content in yeast cells were evaluated (Table 3). When yeasts were suffered from environmental stress induced by ethanol (10 and 15%) for 1 h, all yeasts increased their intracellular trehalose contents with the increase of ethanol concentration. The intracellular trehalose contents of SCT (S. cerevisiae with overexpression of tps1 gene) and SCTA (S. cerevisiae with co-overexpression of tps1 and ari1 genes) did not show significant difference under conditions of with/without ethanol stress (p > 0.05). SCTΔN obtained significant higher intracellular trehalose content than SCT (p < 0.05), as well as SCTAΔN was compared with SCTA. High intracellular trehalose content in SCTΔN and SCTAΔN was due to the effect of nth1 deletion. SCTAΔN showed significantly higher intracellular trehalose content than SCTΔN (p < 0.05). Overexpression of ari1 did not increase the trehalose content in SCT, but it did increase the trehalose content in SCTΔN.

Table 3.

Intracellular trehalose content of yeast cells under non stress and stress conditions.

| Intracellular trehalose content of cell (mg/g dry weight) under stress |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol concentration | 0% | 10% | 15% | Reference or source |

| SC | 9.2 ± 0.2dx | 25.3 ± 2.5dy | 63.7 ± 0.9dz | Divate et al., 2016 |

| SCT | 12.2 ± 0.6cx | 33.0 ± 1.8cy | 67.8 ± 0.7cz | Divate et al., 2016 |

| SCTA | 14.3 ± 2.1cx | 35.3 ± 1.0cy | 70.5 ± 2.0cz | This study |

| SCTΔN | 24.9 ± 1.4bx | 59.9 ± 1.6by | 85.1 ± 0.2bz | Divate et al., 2016 |

| SCTAΔN | 33.1 ± 1.1ax | 71.9 ± 0.7ay | 94.8 ± 3.3az | This study |

SC: Wild type Saccharomyces cerevisiae

SCT: S. cerevisiae with overexpression of tps1 gene

SCTA: S. cerevisiae with co-overexpression of tps1 and ari1 genes

SCTΔN: S. cerevisiae with overexpression of tps1 gene and nth1 gene deletion

SCTAΔN: S. cerevisiae with co-overexpression of tps1and ari1 genes and nth1 gene deletion

Means in the same column followed by different letters are significantly different. One-way ANOVA, Duncan's multiple range test, p < 0.05.

Means in the same row followed by different letters are significantly different. One-way ANOVA, Duncan's multiple range test, p < 0.05.

Gene expression of tps1 and ari1 in SCTAΔN under stress conditions

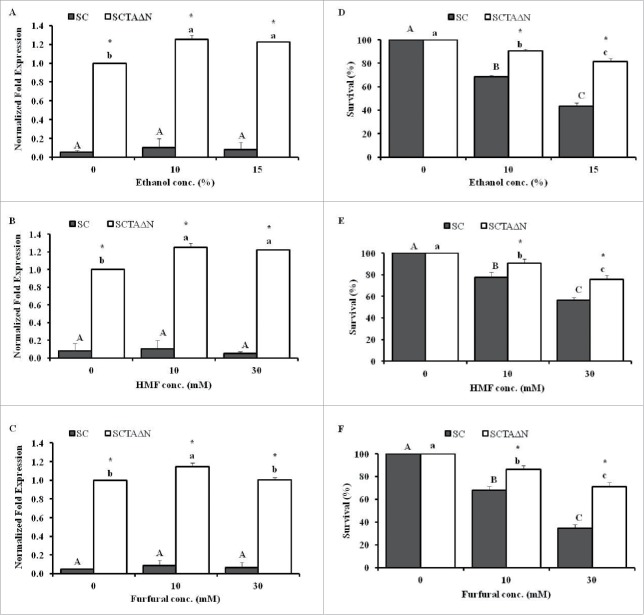

SCTAΔN had the highest intracellular trehalose content, therefore, its gene expression level of tps1 and ari1 was analyzed and compared with wild strain, SC. Compared with SC, SCTAΔN expressed significant higher level of tps1 (p < 0.05), no matter of ethanol concentration in growth medium (Fig. 3A). Ethanol stress induced expression of tps1 in a range of 1.2 to 1.25 fold, however, SCTAΔN did not expressed tps1 differently under 10% and 15% ethanol (p > 0.05). On the other hand, tps1 expression of SC did not be affected by ethanol under tested conditions, and all in a very low level compare with that of SCTAΔN. Similar phenomenon was observed when yeasts were incubated with various concentration of HMF (0, 10 and 30 mM). The gene expression of ari1 was induced to the same level with the present of HMF at 10 and 30 mM in SCTAΔN (Fig. 3B). Expression of ari1 was also induced by 10 mM of furfural but not 30 mM of furfural (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis (A, B, C) and percentage survivors (D, E, F) of SC and SCTAΔN grew in a YPD broth with ethanol conc. (0%, 10%, and 15%) for tps1 gene (A, D), HMF conc. (0 mM, 10 mM, and 30 mM) for ari1 gene (B, E) and furfural conc. (0 mM, 10 mM, and 30 mM) for ari1 gene (C, F). Data are presented as the means ± SD (n = 3). *Significantly higher than the other group. One-way ANOVA, Student's t test, p < 0.05. Bar values with the different letters (A, B, C for SC and a, b, c for SCTAΔN) are significantly different. One-way ANOVA, Duncan's multiple range tests, p < 0.05.

When incubated in YPD broth for 1 h, SC and SCTAΔN did not show significant difference in their viability (Fig. 3D, 3E and 3F), however, the difference emerged under stress conditions induced by ethanol (Fig. 3D), HMF (Fig. 3E) and furfural (Fig. 3F). SCTAΔN showed significantly higher survival than SC when it was confronted with environmental stresses (p < 0.05).

Overexpression of tps1 resulted in increasing synthesis of trehalose in yeast cells, which functioned as a very efficient defense mechanism against ethanol stress. Overexpression of ari1 resulted in increasing activity of aldehyde reductases in yeast cells, which reduced the toxicity of aldehydes toward yeast cells.

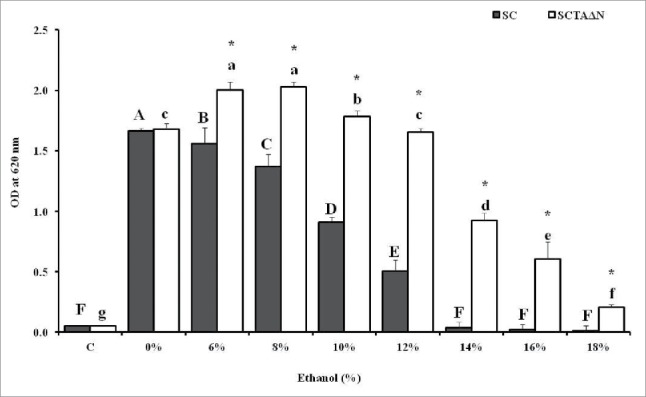

Effects of ethanol concentrations on cell growth

To further understand the effect of ethanol on the growth of SCTAΔN, cells were cultured in YPD medium containing 0 to 18% (v/v) ethanol and incubated at 30°C for 24 h (Fig. 4). Without ethanol stress, SCTAΔN did not grew better than wild strain, SC (p > 0.05). However, when the medium contained 6% or more ethanol, SCTAΔN showed superior growth over SC (p < 0.05). The growth of SCTAΔN was inhibited by ethanol concentrations greater or equal to 14%, while 6% ethanol could slow the growth of SC. When the media contained 14 to 18% ethanol, SC showed no growth in 24 h. When SCTAΔN was incubated under 10 and 15% ethanol for 1 h, its viability decreased but its intracellular trehalose content increased (Fig. 3D and Table 3). SCTAΔN showed higher value of OD620 at YPD containing 6–10% ethanol than that of at YPD without adding ethanol (Fig. 4) indicating that under ethanol stress conditions higher trehalose was accumulated and played a dual role as stress protectant and carbohydrate energy storage.

Figure 4.

Effect of ethanol concentrations on 24 h growth of wild strain (SC) and engineered strain (SCTAΔN). Control (C) is the initial OD of strains. Data are presented as the means ± SD (n = 3). *Significantly higher than the other group. One-way ANOVA, Student's t test, p < 0.05. Bar values with the different letters (A, B, C, D, E, F for SC, while a, b, c, d, e, f, g for SCTΔN) are significantly different. One-way ANOVA, Duncan's multiple range test, p < 0.05.

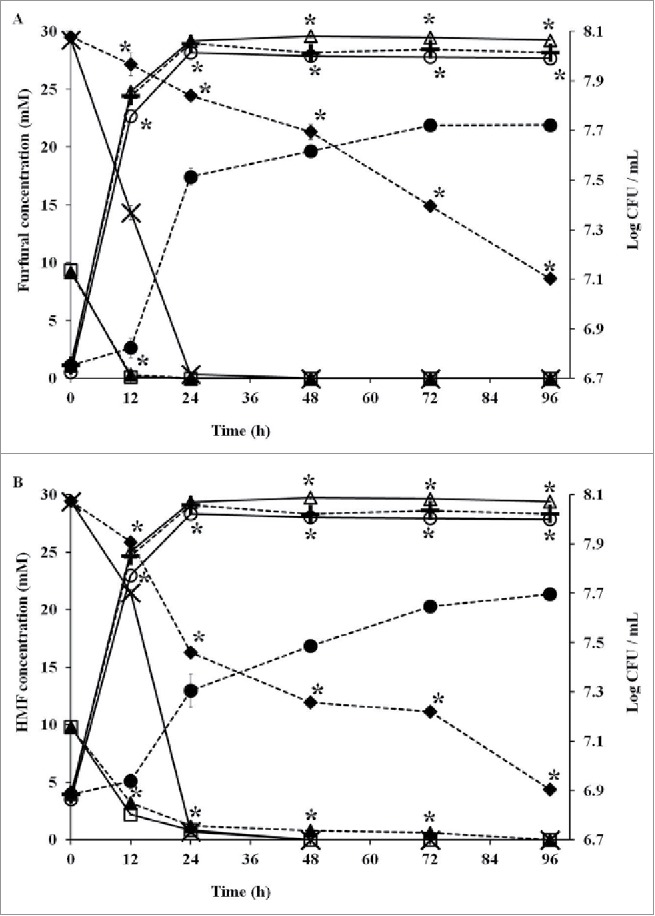

Capacities of furfural and HMF reduction

To compare the capacity to reduce aldehydes, SC and SCTAΔN were incubated independently under the challenge of furfural (10 mM, 30 mM) or HMF (10 mM, 30 mM) in YPD broth. Both SC and SCTAΔN completely degraded 10 mM of furfural in 12 h. When the medium contained 30 mM of furfural, furfural was totally reduced by SCTAΔN in 24 h; however, 8.64 ± 0.35 mM of furfural was remained after incubation with SC for 96 h (Fig. 5A). Both SCTAΔN and SC reduced 10 mM of HMF efficiently (Fig. 5B). When HMF was increased to 30 mM, SC needed more than 96 h to accomplish reduction and SCTAΔN almost finished reduction in 24 h. Compared with SC, SCTAΔN showed greater capacity on reduction of furfural or HMF (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Furfural (A) or HMF (B) degradation capacities and biomass of wild strain (SC) and recombinant strain (SCTAΔN). Data are presented as the means ± SD (n = 3). *Significantly higher than the other group. One-way ANOVA, Student's t test, p < 0.05.  SC at 10 mM furfural/HMF;

SC at 10 mM furfural/HMF;  SC at 30 mM furfural/HMF;

SC at 30 mM furfural/HMF;  SCTAΔN at 10 mM furfural/HMF;

SCTAΔN at 10 mM furfural/HMF;  SCTAΔN at 30 mM furfural/HMF;

SCTAΔN at 30 mM furfural/HMF;  viability of SC at 10 mM furfural/HMF;

viability of SC at 10 mM furfural/HMF;  viability of SC at 30 mM furfural/HMF;

viability of SC at 30 mM furfural/HMF;  viability of SCTAΔN at 10 mM furfural/HMF;

viability of SCTAΔN at 10 mM furfural/HMF;  viability of SCTAΔN at 30 mM furfural/HMF.

viability of SCTAΔN at 30 mM furfural/HMF.

SC and SCTAΔN showed similar growth rate when medium contained 10 mM of furfural or HMF. Growth of SC was decreased by 30 mM of furfural or HMF, while SCTAΔN was not affected under the same condition (Fig. 5A, B).

The above results indicated that overexpression of ari1 gene in engineered strain (SCTAΔN) enhanced reduction of aldehydes and increased cell viability as well.

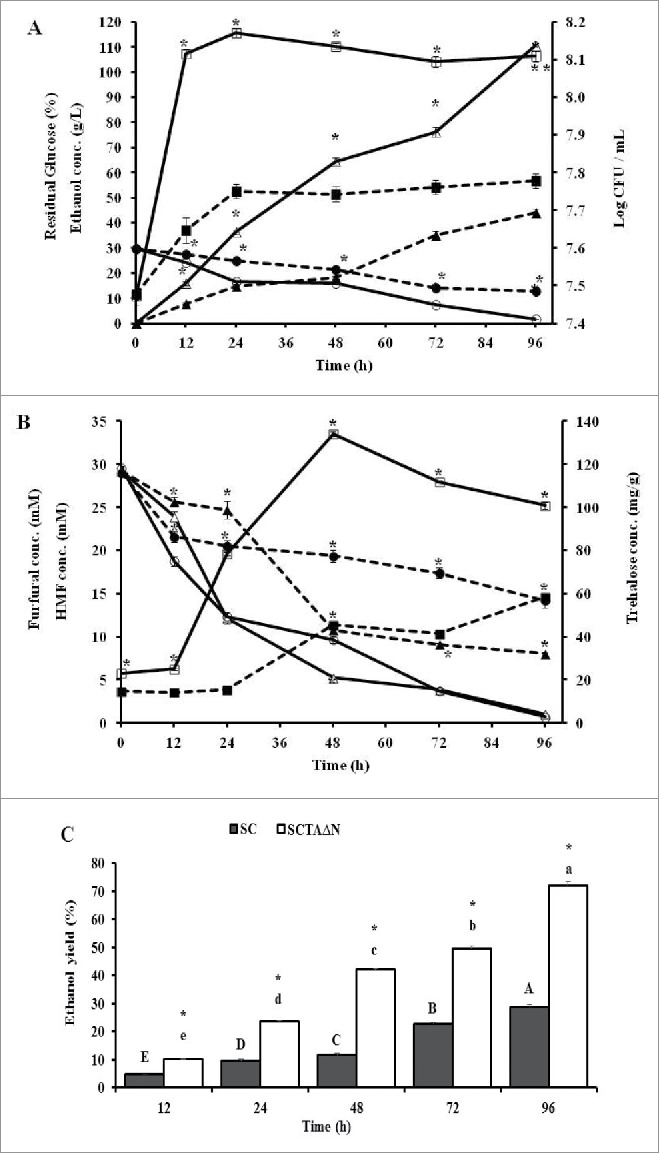

Ethanol production under high stress conditions

The ethanol productivity of SCTAΔN was compared with that of SC under high stress conditions induced by combined effects of 30% glucose, 30 mM furfural and 30 mM HMF (Fig. 6A). After incubation for 96 h, both SCTAΔN and SC produced maximum amount of ethanol, and the ethanol concentration were 110.59 ± 0.28 g/L and 44.03 ± 1.43 g/L, respectively. At the end of processes, 12.70 ± 0.10% glucose was remained in fermentation broth using SC as starter, whereas the glucose in medium was almost used up by SCTAΔN (1.67 ± 0.03% residual glucose). Biomasses of SC and SCTAΔN reached their peaks at 24 h incubation, and SCTAΔN showed better growth in the high stress conditions than SC.

Figure 6.

Ethanol production capacities of wild strain (SC) and engineered strain (SCTAΔN) grown in YP broth (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone) containing 30 % glucose, 30 mM furfural and 30 mM HMF. Data are presented as the means ± SD (n = 3). *Significantly higher than the other group. One-way ANOVA, Student's t test, p < 0.05. Bar values of the ethanol yield (%) with the different letters (A, B, C, D, E, F for SC and a, b, c, d, e, f for SCTAΔN) are significantly different. One-way ANOVA, Duncan's multiple range tests, p < 0.05. A: Ethanol concentration in g/L ( SC;

SC;  SCTAΔN), residual glucose concentration in % (

SCTAΔN), residual glucose concentration in % ( SC;

SC;  SCTAΔN) and biomass Log CFU/mL (

SCTAΔN) and biomass Log CFU/mL ( SC;

SC;  SCTAΔN). B: HMF concentration in mM (

SCTAΔN). B: HMF concentration in mM ( SC;

SC;  SCTAΔN), furfural concentration in mM (

SCTAΔN), furfural concentration in mM ( SC;

SC;  SCTAΔN) and Trehalose concentration in mg/g dry cells weight (

SCTAΔN) and Trehalose concentration in mg/g dry cells weight ( SC;

SC;  SCTAΔN). C: Ethanol yield (%) until 96 h of incubation.

SCTAΔN). C: Ethanol yield (%) until 96 h of incubation.

After incubation for 96 h, HMF in fermentation broth was reduced to 8.03 ± 0.12 mM and 1.05 ± 0.03 mM by SC and SCTAΔN, respectively (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, furfural was almost completely reduced by SCTAΔN in which broth contained 0.69 ± 0.03 mM of furfural. Significant amount of furfural (14.21 ± 0.83 mM) was not reduced by the SC. Intracellular trehalose of SC was gradually increased during growth and reached to 58.54 ± 0.74 mg/g. SCTAΔN had the highest trehalose accumulation (134.05 ± 1.18 mg/g) after incubation for 48h.

The time course of theoretical ethanol yields for SC and SCTAΔN was shown on Fig. 6C. These two strains converted glucose into ethanol continuously during 96 h. Ethanol yields of SCTAΔN were significantly higher than that of SC (p < 0.05). SCTAΔN achieved a great efficiency in ethanol production (72.14 ± 0.18%), while, SC got 28.72 ± 0.93% of ethanol yield.

Discussion

Single insertion event (SCT with insertion of tps1 gene) is much more likely to happen but the occurrence of multiple insertion may be 1–10% that of single insertion events. To locate these “jack-pot” clones of transformants with multiple insertions of tps1 gene and ari1 gene (SCTA and SCTAΔN), we screened more than hundreds of Zeocin-resistant transformants.

Trehalose is a nonreducing disaccharide, in which 2 glucoses are linked with an α,α-1,1 glycosidic linkage. Trehalose functions as a protector for cell membranes and cellular proteins under environmental stresses such as heat, cold, desiccation, dehydration, ethanol, oxidation and anoxia.22,26,27 In yeast, trehalose level is low under favorable growth condition but is induced by environmental stresses. However, Ratnakumar and Tunnacliffe28 suggested that there was no consistent relationship between intracellular trehalose concentration and desiccation tolerance in S. cerevisiae. In our previous study,25 SCTΔN (S. cerevisiae with overexpression of tps1 gene and deletion of nth1 gene) showed not only the highest accumulated intracellular trehalose but the greatest tolerance under stress conditions compare with SCT (S. cerevisiae with overexpression of tps1 gene) and wild strain. Consistent with those results, engineered strain SCTAΔN (co-overexpression of tps1 gene and ari1 gene, and deletion of nth1 gene) constructed in this study showed higher trehalose content than SCTΔN under favorable/stress condition. Compared with SCTΔN, SCTAΔN exhibited greater viability under stresses induced by ethanol or high glucose osmosis confirming the defense mechanism of intracellular trehalose.

Furfural and HMF, the most important aldehyde inhibitors in lignocellulosic hydrolysates, are known to affect the growth and fermentation performance of S. cerevisiae. However, S. cerevisiae has the natural ability to reduce furfural and HMF to their corresponding less toxic alcohols by multiple dehydrogenases/reductases.12,15,29 Researchers stated that, overexpression of the dehydrogenase/reductase genes (ari1, adh7, ald6 and adh6) increased enzyme activities for furfural and/or HMF reduction and simultaneously improved the tolerability of yeast against inhibitors.12-14,30

Quantitative real-time PCR data confirmed the overexpression of tps1 and ari1 in engineered strain SCTAΔN. As compare with wild strain (SC), SCTAΔN exhibited significantly higher cell survival under stresses of ethanol, furfural and HMF. The engineered strain (SCTAΔN) showed significantly higher ethanol tolerance which might be due to overexpression of tps1 that results in more trehalose accumulation. Similarly, overexpression of ari1 in SCTAΔN increased the enzyme activities for furfural and/or HMF reduction and improves the tolerability toward them.

When the medium contained 10 mM furfural and/or HMF; cell growth and reduction capacities of SC and SCTAΔN were almost similar (Fig. 5A, B). As the concentrations were increased to 30 mM; SCTAΔN showed significantly greater growth and furfural and/or HMF reduction capacity than the wild strain SC (p < 0.05). Overexpression of ari1 (aldehyde reductase) improved the inhibitor tolerance and cell viability of engineered strain. Liu and Moon12 stated that aldehyde reductase gene is involved in the detoxification of aldehyde inhibitors.

Under the stresses of 30% glucose, 30 mM furfural and 30 mM HMF engineered strain SCTAΔN showed greater performance. Compared with SC, SCTAΔN showed better capacity on converting glucose to ethanol, reducing HMF and furfural to less toxic compounds, and generating intracellular trehalose. The high accumulation of intracellular trehalose and overexpression of ari1 in SCTAΔN provided the cells high tolerance against the high environmental stresses induced by combining stresses of glucose, HMF and furfural.

Overexpression of tps1 (trehalose-6-phosphate synthase) and removal of nth1 (neutral trehalase) improved the intracellular trehalose level and ethanol tolerance. A positive correlation was observed between cell viability and trehalose concentration because intracellular trehalose prevents the ethanol-induced electrolyte leakage in yeast cells.31 Moreover, overexpression of ari1 (aldehyde reductase) improved the enzyme activities for furfural and/or HMF reduction and inhibitor tolerance. Yeast strain with overexpression of aldehyde reductase gene showed not only more tolerant response to furfural and HMF, but earlier recoveries and a better growth as compare with wild type yeast strain.12 All these aspects of the strain improvement played an important role in cell viability as well as ethanol production under several different stress conditions.

The engineered strain (tps1 gene overexpression, ari1 gene overexpression and nth1 gene deletion) presented in this study exhibited increased viability and intracellular trehalose content with high ethanol yield under glucose, furfural, HMF and ethanol stress conditions. This strategy of strain improvement might provide a preferable reuse of starters as immobilized cells and even provide applications in continuous processes.

Conclusion

This study describes the construction of stress tolerant yeast strain to increase intracellular trehalose concentration and to improve its tolerability toward the aldehyde inhibitors. The strain was improved by overexpression of tps1 gene, ari1 gene and the entire deletion of nth1 gene. During this study we found that engineered strain was more tolerant to environmental stresses and aldehyde inhibitors. Compared to the wild strain, the engineered strain exhibited not only higher trehalose accumulation, but cell viability as well as increased furfural and/or HMF reduction capacity. The novel strain constructed in this study will be promising for bioethanol production from lignocellulosic materials and agricultural residues.

Materials and methods

Strains, vectors, and media

All the strains and vectors used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli TOP10F’ was purchased from Novagen Inc. (Wisconsin, USA) and S. cerevisiae (BCRC 21685) was purchased from Bioresource Collection and Research Center, Food Industry Research and Development Institution, Shinchu, Taiwan. The expression vector pGAPZαC, purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA), was used for ari1 gene overexpression study. Recombinant vectors were multiplied in E. coli TOP10F’.

Table 1.

Strains and vectors used in this study.

| Strains or vectors | Properties or product | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli TOP10F’ | F’ [lacIq Tn10(Tetr)] mcrA (mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) 80lacZM15 lacX74 recA1araD139 (ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA |

| S. cerevisiae (BCRC 21685) (SC) | Wild type | Bioresources Collection and Research Center, Taiwan |

| Sacchromyces cerevisiae with overexpression of tps1 gene (SCT) | Carrying pGAPZC-tps1 vector | Divate et al., 2016 |

| Sacchromyces cerevisiae with overexpression of tps1 and ari1 gene (SCTA) | Carrying pGAPZC-tps1 vector and pGAPZC-ari1 vector | This study |

| Sacchromyces cerevisiae with overexpression of tps1 gene and deletion of nth1 gene (SCTΔN) | Carrying pGAPZC-tps1 vector and gene disruption cassette | Divate et al., 2016 |

| Sacchromyces cerevisiae with overexpression of tps1, ari1 genes and deletion of nth1 gene (SCTAΔN) | Carrying pGAPZC-tps1 vector, pGAPZC-ari1 vector and gene disruption cassette | This study |

| pGAPZαC | Expression Vector, GAP promoter, Sh ble gene (Zeocin™ resistance gene) | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA |

| pGAPZC-ari1 | pGAPZαC vector carrying a ari1 gene | This study |

E. coli and yeast were maintained and cultivated in Luria-Bertani (LB) (10 g/L peptone, 10 g/L NaCl, and 5 g/L yeast extract) medium at 37°C and YPD (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 20 g/L dextrose) medium at 28°C, respectively. To select the Zeocin resistant transformants, low salt LB (10 g/L peptone, 5 g/L NaCl, and 5 g/L yeast extract) plates were supplemented with 25 mg/L Zeocin (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, California, USA) and YPD plates were supplemented with 100 mg/L Zeocin. All parental strains and engineered strains were maintained in 30% glycerol at −80°C. Vectors within the host cells were extracted using Gene-spin miniprep plasmid purification kit (Protech Technology, Taipei, Taiwan). Yeast genomic DNA (gDNA) was prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol (Genomic DNA purification kit, BioKit, Miaoli, Taiwan).

Primers

Table 2 lists the primers used in this study. These primers were designed according to the website of NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) for nucleotide sequences of tps1 gene (GenBank ID:NM_001178474.1), ari1 gene (GenBank ID:NM_001181022.3), taf10 gene (GenBank ID: NM_001180474.3) and genomic DNA of S. cerevisiae.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence 5′−3′ | Restriction site | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ari1-F | TCGTTCGAAAAAATGGCGACTACTGATACCACTGTTTTCGTTTCTG | BstBI | ari1 gene amplification |

| Ari1-R | TCGCTCGAGTTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGGGCTTCATTTTGAACTTC | XhoI | |

| VTF | TTCGAAACGATGGGTACTAC | — | Verification of tps1 or ari1 gene insertion |

| VAF | TTCGAAAAAATGGGTACTAC | — | |

| VR | AGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGG | — | |

| qTps1-F | TTGTGGTGTCCAACAGGCTT | — | quantitative real-time PCR |

| qTps1-R | GGACGACATTGCGTACTCGT | — | |

| qAri1-F | TTGTGCTACACACTGCCTCC | — | |

| qAri1-R | CGTTCACTGCAGGGGTTAGT | — | |

| qTaf10-F | TCCAGGATCAGGTCTTCCGT | — | |

| qTaf10-R | TGTCCTTGCAATAGCTGCCT | — |

The underlined bases encode restriction site and italicized bases encode 6xHis-tag.

Genetic manipulation

Genomic DNA of S. cerevisiae wild strain was used as the template to amplify ari1 gene by PCR with primers of Ari1-F and Ari1-R. DNA thermal cycler (Labcycler Gradient, SENSQUEST, Gottingen, Germany) was used to obtain the PCR products. All PCR products were electrophoresed, observed by ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining and purified with a Clean/Gel Extraction Kit (BioKit, Miaoli, Taiwan). The BstBI-XhoI fragment carrying the ari1 gene was digested and ligated into the expression vector, pGAPZαC which was pre-digested with same restriction enzymes. The resulting vector was designated as pGAPZC-ari1. To amplify pGAPZC-ari1, recombinant vector was transformed into CaCl2-treated E. coli TOP10F’ according to Hanahan and Meselson.32

SCT (S. cerevisiae with tps1 gene overexpression) and SCTΔN were constructed in our previous study25 and further used in this study for ari1 gene overexpression. Prior to transformation, pGAPZC-ari1 was linearized by AvrII enzyme. Yeast transformation was performed by electroporation method according to the manufacture's protocol (MicroPulser electroporation apparatus, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). To generate SCTA and SCTAΔN, pGAPZC-ari1 was transformed into SCT and SCTΔN, respectively (Fig. 1). The colonies were selected by plating on YPDS plates (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 20 g/L dextrose, 1 M sorbitol) containing 100 mg/L Zeocin. Transformants were confirmed by PCR using VTF (for tps1 gene) or VAF (for ari1 gene) as forward primers and VR as reverse primer in same PCR reaction tube.

Figure 1.

Multiple insertion events in yeast genome by using expression vectors pGAPZC-tps1 and pGAPZC-ari1.

Protein extraction, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and Western blot analysis

Frozen culture (1 mL) was activated and grown in YPD broth at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm). Yeast pellet (100 mg) was used for proteins extraction.33 SDS- PAGE was performed according to Laemmli.34 For western blotting, protein bands on the gel were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA, USA) using Mini-Trans-Blot system (BioRad Laboratory, Inc., USA). Blots were probed with Anti-His tag, Clone His.H8 (Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany; 1:5000 dilution), and visualized with a 1:5000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (Jackson immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA). Chemiluminescence detection was performed with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and detected with a CCD-camera (Fusion-SL 3500.WL; Peqlab Biotechnologie, Erlangen, Germany).

Measurement of trehalose concentration

Frozen culture (1 mL) was activated and grown in YPD broth at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm). To measure the intracellular trehalose concentration under ethanol stress, the culture was transferred into 100 mL of YPD broth to achieve an OD620 value of 0.3 and incubated in a 500 mL baffled Erlenmeyer Flask at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm) for 24 h. After incubation, cells were collected by centrifugation and transferred into fresh YPD broth (100 mL) containing ethanol (0%, 10%, and 15%) and incubated at same conditions for another 1 h.

After stress treatment, cells were collected by centrifugation at 7000 × g for 5 min and dried at 100°C for 12 h. To extract trehalose, a pellet of 40 mg was mixed with 2 mL ethanol (99.5%) and incubated in a boiling water bath for 1 h. For HPLC analysis of trehalose, extracts were suspended in 0.5 mL of acetonitrile: water (1:1). Acetonitrile: water (7:3) was used as the mobile phase. The HPLC system was equipped with a refractive index detector and a Lichrocart® 250–4 Purospher® Star NH2 column (5 µm) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).35

Quantification of gene expression by real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

Frozen culture (1 mL) was activated and grown in YPD broth at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm). For stress treatment study, the culture was transferred into fresh YPD medium and incubated under the same conditions. When the OD620 reached approximately 1.0, cells were collected by centrifugation and transferred into fresh YPD broth (100 mL) containing ethanol (0%, 10%, 15%), furfural (0 mM, 10, mM, 30 mM) or HMF (0 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM) in a 500 mL baffled Erlenmeyer Flasks. Cells were incubated at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm) for another 1 h. Stress tolerance was expressed as percentage of survivors.

For gene expression study, Cells were collected by centrifugation at 7000 × g for 5 min and used for RNA isolation. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentration and quality were assessed spectrophotometrically. Total RNA (1 µg) was subjected to reverse transcription using the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed with iQ SYBR Green Supermix according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). The MiniOpticon™ system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to quantify the expression levels of tps1 and ari1. Amplifications were performed under the following conditions: 95°C for 3 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 s and at 57.8°C for 30 s, and final extension at 95°C for 10 s. Gene expression levels of tps1 and ari1 were normalized to an internal control taf10 gene.36 Analyses were performed with the Bio-Rad CFX manager 2.1 software.

Ethanol tolerance

Ethanol tolerance was determined as mentioned in our previous study25 Cells were adjusted to an OD620 value of 0.05 with YPD containing 0–18% ethanol and incubated in the wells of a 96-well flat bottom polystyrene microtiter plate (Costar, Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) sealed with a gas-permeable sealing membrane (Breathe Easy membrane, Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) at 30°C.37 The growth of yeasts was monitored by measurement of OD620 with a microplate reader (Fluostar optima, BMG Labtech, Germany).

Furfural and HMF reduction capacities

Frozen culture (1 mL) was activated and grown in YPD broth at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm). To measure furfural and HMF reduction capacities, the culture was transferred into 100 mL of YPD broth containing furfural or HMF (10 mM and 30 mM) to achieve an OD620 value of 0.3 and incubated in a 500 mL baffled Erlenmeyer Flask at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm). Samples were withdrawn at the indicated time intervals for determination of furfural and HMF concentrations and viable cell count.

Supernatant was collected by centrifuging at 10,000 × g for 10 min and filtering through a 0.45 μm membrane. The HPLC system was equipped with a refractive index detector and ICSep ICE-COREGEL 87H3 column (Transgenomic, Omaha, USA). The mobile phase was 5 mM H2SO4 with a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min.38

Ethanol production capacity under stress conditions

Frozen culture (1 mL) was activated and grown in YPD broth at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm). Cells were collected and centrifuged at 4000 × g for 5 min. The collected cells (3 × 107 cells/mL) were transferred into 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL of fermentation broth (1%, yeast extract, 2% peptone, 30% glucose, 30 mM furfural, and 30 mM HMF). The flasks were incubated statically at 30°C and samples were withdrawn at the indicated time intervals and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, filtered through 0.45 μm membranes and used for analysis of glucose, ethanol, furfural and HMF concentration by HPLC.39 Pellet was used for trehalose extraction as mentioned above. The HPLC system was equipped with a refractive index detector and ICSep ICE-COREGEL 87H3 column (Transgenomic, Omaha, USA). The mobile phase was 5 mM H2SO4 with a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min.38 The ethanol yield was calculated according to the following equation:40 Ethanol yield (%) = [gm ethanol produced / (gm glucose in medium × 0.511)] × 100.

Viable cell count

Sample was serially diluted as required and spread on YPD agar plates and plates were incubated at 30°C for 72 h. Viable cells were counted as colony forming units (CFU)/mL sample.

Statistical analysis

Trehalose concentration, ethanol concentration, glucose concentration, furfural concentration, HMF concentration, gene expression and biomass values were evaluated by one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan's new multiple-range test to determine the differences among means or Student's t-test when only 2 groups were compared using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA). A significance level of 5% was adopted for all comparisons.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, R.O.C. Taiwan (NSC 100–2313-B-126–001-MY3). Its financial support is greatly appreciated.

References

- [1].Boopathy R, Bokang H, Daniels L. Biotransformation of furfural and 5-hydroxymethyl furfural by enteric bacteria. J Ind Microbiol 1993; 11:147-50; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF01583715 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Larsson S, Palmqvist E, Hahn-Hägerdal B, Tengborg C, Stenberg K, Zacchi G, Nilvebrant NO. The generation of fermentation inhibitors during dilute acid hydrolysis of softwood. Enzyme Microb Technol 1999; 24:151-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0141-0229(98)00101-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Khan QA, Hadi SM. Inactivation and repair of bacteriophage lambda by furfural. Biochem Mol Biol Int 1994; 32:379-85; PMID:8019442 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Modig T, Lidén G, Taherzadeh MJ. Inhibition effects of furfural on alcohol dehydrogenase, aldehyde dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase. Biochem J 2002; 363:769-76; PMID:11964178; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/bj3630769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sanchez B, Bautista J. Effects of furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural on the fermentation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and biomass production from Candida guilliermondii. Enzyme Microb Technol 1988; 10:315-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0141-0229(88)90135-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Liu, Z. L. and Blaschek, H. P (2010) Biomass Conversion Inhibitors and In Situ Detoxification, in Biomass to Biofuels: Strategies for Global Industries (eds A. A. Vertès, N. Qureshi, H. P. Blaschek and H. Yukawa). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/9780470750025.ch12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Diaz DME, Villa P, Guerra M, Rodriguez E, Redondo D, Martinez A. Conversion of furfural into furfuryl alcohol by Saccharomyces cervisiae 354. Acta Biotechnol 1992; 12:351-4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/abio.370120420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Horváth IS, Franzén CJ, Mohammad J, Sa I, Taherzadeh MJ. Effects of Furfural on the Respiratory Metabolism of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in Glucose-Limited Chemostats. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003; 69:4076-86; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.69.7.4076-4086.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Taherzadeh MJ, Gustafsson L, Niklasson C, Lidén G. Physiological effects of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural on Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2000; 53:701-8; PMID:10919330; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s002530000328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Liu ZL, Slininger PJ, Gorsich SW. Enhanced biotransformation of furfural and hydroxymethylfurfural by newly developed ethanologenic yeast strains. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2005; 121–124:451-60; PMID:15917621; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1385/ABAB:121:1-3:0451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Liu ZL, Slininger PJ, Dien BS, Berhow MA, Kurtzman CP, Gorsich SW. Adaptive response of yeasts to furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and new chemical evidence for HMF conversion to 2,5-bis-hydroxymethylfuran. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2004; 31:345-52; PMID:15338422; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10295-004-0148-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Liu ZL, Moon J. A novel NADPH-dependent aldehyde reductase gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae NRRL Y-12632 involved in the detoxification of aldehyde inhibitors derived from lignocellulosic biomass conversion. Gene 2009; 446:1-10; PMID:19577617; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gene.2009.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Park SE, Koo HM, Park YK, Park SM, Park JC, Lee OK, Park YC, Seo JH. Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 6 reduces inhibitory effect of furan derivatives on cell growth and ethanol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Bioresour Technol 2011; 102:6033-8; PMID:21421300; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.02.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Petersson A, Almeida JRM, Modig T, Karhumaa K, Hahn-Hägerdal B, Gorwa-Grauslund MF, Lidén G. A 5-hydroxymethyl furfural reducing enzyme encoded by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ADH6 gene conveys HMF tolerance. Yeast 2006; 23:455-64; PMID:16652391; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/yea.1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhao X, Tang J, Wang X, Yang R, Zhang X, Gu Y, Li X, Ma M. YNL134C from Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a novel protein with aldehyde reductase activity for detoxification of furfural derived from lignocellulosic biomass. Yeast 2015; 32:409-22; PMID:25656244; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/yea.3068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jain NK, Roy I. Effect of trehalose on protein structure. Protein Sci 2009; 18:24-36; PMID:19177348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Singer MA, Lindquist S. Multiple effects of trehalose on protein folding in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell 1998; 1:639-48; PMID:9660948; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80064-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bandara A, Fraser S, Chambers PJ, Stanley GA. Trehalose promotes the survival of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during lethal ethanol stress, but does not influence growth under sublethal ethanol stress. FEMS Yeast Res 2009; 9:1208-16; PMID:19799639; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li L, Ye Y, Pan L, Zhu Y, Zheng S, Lin Y. The induction of trehalose and glycerol in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in response to various stresses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009; 387:778-83; PMID:19635452; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mahmud SA, Nagahisa K, Hirasawa T, Yoshikawa K, Ashitani K, Shimizu H. Effect of trehalose accumulation on response to saline stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2009; 26:17-30; PMID:19180643; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/yea.1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Soto T, Fernández J, Vicente-Soler J, Cansado J, Gacto M. Accumulation of trehalose by overexpression of tps1, coding for trehalose-6-phosphate synthase, causes increased resistance to multiple stresses in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999; 65:2020-4; PMID:10223994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mahmud SA, Hirasawa T, Shimizu H. Differential importance of trehalose accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in response to various environmental stresses. J Biosci Bioeng 2010; 109:262-6; PMID:20159575; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.08.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bell W, Sun W, Hohmann S, Wera S, Reinders A, De Virgilio C, Wiemken A, Thevelein JM. Composition and functional analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae trehalose synthase complex. J Biol Chem 1998; 273:33311-9; PMID:9837904; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nwaka S, Holzer H. Molecular biology of trehalose and the trehalases in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 1998; 58:197-237; PMID:9308367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60037-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Engineering Saccharomyces cerevisiae for improvement in ethanol tolerance by accumulation of trehalose. Bioengineered 7(6):445–458. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/21655979.2016.1207019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Crowe JH, Crowe LM, Chapman D. Preservation of membranes in anhydrobiotic organisms: the role of trehalose. Science 1984; 223:701-3; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.223.4637.701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tapia H, Young L, Fox D, Bertozzi CR, Koshland D. Increasing intracellular trehalose is sufficient to confer desiccation tolerance to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:6122-7; PMID:25918381; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1506415112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ratnakumar S, Tunnacliffe A. Intracellular trehalose is neither necessary nor sufficient for desiccation tolerance in yeast. FEMS Yeast Res 2006; 6:902-13; PMID:16911512; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00066.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jönsson LJ, Alriksson B. Nilvebrant N-O. Bioconversion of lignocellulose: inhibitors and detoxification. Biotechnol Biofuels 2013; 6:16; PMID:23356676; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1754-6834-6-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Liu ZL, Moon J, Andersh BJ, Slininger PJ, Weber S. Multiple gene-mediated NAD(P)H-dependent aldehyde reduction is a mechanism of in situ detoxification of furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2008; 81:743-53; PMID:18810428; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00253-008-1702-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mansure JJC, Panek AD, Crowe LM, Crowe JH. Trehalose inhibits ethanol effects on intact yeast cells and liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta - Biomembr 1994; 1191:309-16; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90181-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hanahan D, Meselson M. Plasmid screening at high colony density. Gene 1980; 10:63-7; PMID:6997135; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0378-1119(80)90144-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Horvath A, Riezman H. Rapid protein extraction from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 1994; 10:1305-10; PMID:7900419; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/yea.320101007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970; 227:680-5; PMID:5432063; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/227680a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ferreira JC, Paschoalin VMF, Panek AD, Trugo LC. Comparison of three different methods for trehalose determination in yeast extracts. Food Chem 1997; 60:251-4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0308-8146(96)00330-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Teste MA, Duquenne M, François JM, Parrou JL. Validation of reference genes for quantitative expression analysis by real-time RT-PCR in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Mol Biol 2009; 10:99; PMID:19874630; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2199-10-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tran TMT, Stanley GA, Chambers PJ, Schmidt SA. A rapid, high-throughput method for quantitative determination of ethanol tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ann Microbiol 2013; 63:677-82; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s13213-012-0518-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kupiainen L, Ahola J, Tanskanen J. Kinetics of glucose decomposition in formic acid. Chem Eng Res Des 2011; 89:2706-13; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cherd.2011.06.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wirawan F, Cheng CL, Kao WC, Lee DJ. Chang J-S. Cellulosic ethanol production performance with SSF and SHF processes using immobilized Zymomonas mobilis. Appl Energy 2012; 100:19-26; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.04.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hatzis C, Riley C, Philippidis GP. Detailed material balance and ethanol yield calculations for the biomass-to-ethanol conversion process. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 1996; 57–58:443-59; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02941725 [DOI] [Google Scholar]