Summary

Robust progression through the cell-division cycle depends on the precisely ordered phosphorylation of hundreds of different proteins by cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and other kinases. The order of CDK substrate phosphorylation depends on rising CDK activity, coupled with variations in substrate affinities for different CDK-cyclin complexes and the opposing phosphatases [1–4]. Here we address the ordering of substrate phosphorylation by a second major cell-cycle kinase, Cdc7-Dbf4 or Dbf4-dependent kinase (DDK). The primary function of DDK is to initiate DNA replication by phosphorylating the Mcm2-7 replicative helicase [5–7]. DDK also phosphorylates the cohesin acetyltransferase, Eco1 [8]. Sequential phosphorylations of Eco1 by CDK, DDK, and Mck1 create a phosphodegron that is recognized by the ubiquitin ligase SCFCdc4. DDK, despite being activated in early S phase, does not phosphorylate Eco1 to trigger its degradation until late S phase [8]. DDK associates with docking sites on loaded Mcm double hexamers at unfired replication origins [9, 10]. We hypothesized that these docking interactions sequester limiting amounts of DDK, delaying Eco1 phosphorylation by DDK until replication is complete. Consistent with this hypothesis, we find that overproduction of DDK leads to premature Eco1 degradation. Eco1 degradation also occurs prematurely if Mcm complex loading at origins is prevented by depletion of Cdc6, and Eco1 is stabilized if loaded Mcm complexes are prevented from firing by a Cdc45 mutant. We propose that the timing of Eco1 phosphorylation, and potentially that of other DDK substrates, is determined in part by sequestration of DDK at unfired replication origins during S phase.

Keywords: Eco1, Dbf4, Mcm complex, origins, DDK, CDK

Results

Eco1 degradation coincides with the rise in Dbf4 levels

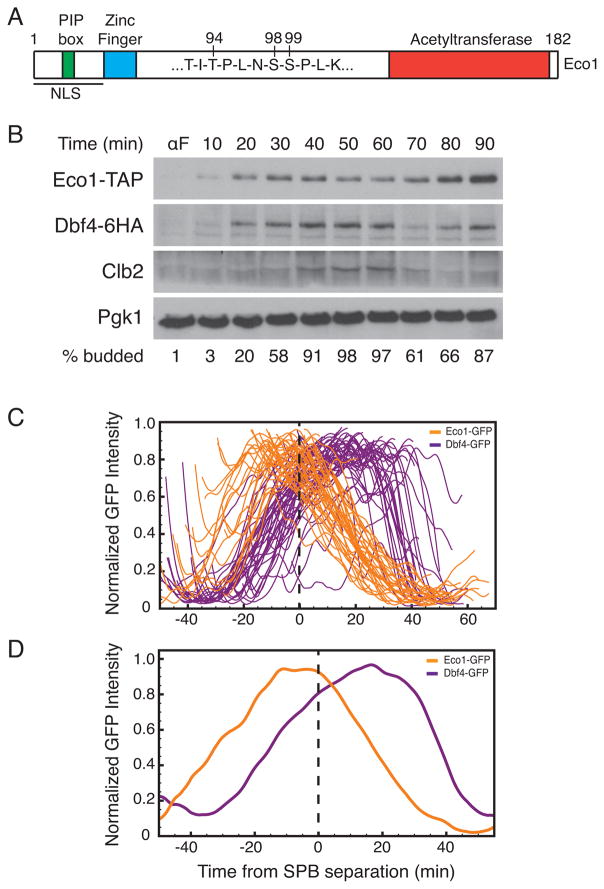

In the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Eco1 is regulated by an unusually complex mechanism that promotes Eco1 degradation via the ubiquitin ligase SCFCdc4 [8, 11]. To create a diphosphodegron motif that is recognized by the Cdc4 subunit of SCFCdc4, Eco1 is phosphorylated in sequence by 3 different protein kinases. First, Cdk1 phosphorylates serine 99. This primes the protein for phosphorylation at an adjacent site (S98) by DDK, which primes Eco1 for phosphorylation at T94 by a third kinase, Mck1 (a homolog of GSK-3 in S. cerevisiae). Phosphorylation by Mck1 results in a diphosphorylated sequence (pT94-x-x-x-pS98) that is recognized by Cdc4, resulting in ubiquitination by SCFCdc4 and destruction by the proteasome (Figure 1A) [8, 11].

Figure 1. Oscillations of Eco1 and Dbf4 during the cell cycle.

(A) Diagram of Eco1 primary structure, depicting the three phosphorylation sites that govern Eco1 degradation. (B) Cells carrying epitope-tagged Eco1 and Dbf4 were arrested in G1 with alpha factor (αF) and released. At the indicated times after release, budding index was determined and cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting. Clb2 was used as a cell cycle marker and Pgk1 was used as a loading control. (C) Asynchronous cells, expressing either Eco1-GFP or Dbf4-GFP, were analyzed by spinning disk confocal microscopy. Images were taken every 30 seconds for 70 minutes. Maximum intensity projections were used to create single cell traces of Eco1-GFP (n=45) or Dbf4-GFP (n=49), aligned in silico to SPB separation. Fluorescence signals were normalized to maximum intensity. Before normalization, peak intensity of Dbf4-GFP was 2.5-fold greater than that of Eco1-GFP. (D) Averaged traces of the single-cell data in (C).

Eco1 is degraded in late S phase, despite the fact that all the kinases that regulate it are active at the beginning of S phase. Previous work [8] demonstrated that Cdk1-dependent phosphorylation of S99 occurs in late G1 or early S phase, but subsequent phosphorylation by DDK is delayed until late S phase. A mutation in Eco1 (ΔN97) that allows degradation in the absence of DDK leads to its degradation in early S phase. Thus DDK, despite being active in early S phase, does not target Eco1 until late S phase.

In our previous work [8, 11], the timing of Eco1 degradation in the cell cycle was estimated by western blotting of lysates from cells released from a G1 arrest. Here, we extended this analysis to determine the timing of Eco1 degradation relative to that of the DDK activator, Dbf4. A yeast strain expressing Eco1-TAP and Dbf4-6HA at endogenous loci was arrested in G1 with alpha factor mating pheromone and then released (Figure 1B). As seen previously, Eco1 levels rose as the cell entered the cell cycle (as indicated by budding) and peaked about 30 minutes after release, after which its levels declined gradually before rising again after mitosis. Dbf4 levels began to rise at cell-cycle entry and peaked after 60 minutes.

To more precisely determine the timing of Eco1 degradation, we used a single-cell method to monitor Eco1 levels during a normal cell cycle. For comparison, we analyzed Dbf4 levels as in our previous work [12]. Eco1 or Dbf4 were each tagged at the endogenous locus with a C-terminal eGFP. Analysis of eGFP-tagged proteins provides an accurate measure of the timing of degradation; however, because eGFP requires 15–30 minutes to fold, the rise in fluorescence signal from these proteins is delayed relative to the synthesis of the protein [13, 14]. A spindle pole body (SPB) component, Spc42, was tagged in these strains with a C-terminal mCherry. SPB behavior provides a way to track the timing of events during the cell cycle: the SPB is duplicated in early S phase, and the two SPBs separate to initiate spindle assembly in early mitosis. The SPBs then separate further as the spindle elongates at anaphase, which coincides with segregation of sister chromatids [12, 15–17]. Initial SPB separation occurs at about the time that S phase is completed [18, 19].

Our single-cell analysis revealed that Eco1-GFP reached peak levels about 10 minutes before SPB separation and began to decline at the same time as SPB separation (Figure 1C and 1D). Thus, the onset of Eco1 degradation coincides roughly with the completion of S phase and initiation of mitosis. As seen in our previous work [12], Dbf4-GFP levels peaked after SPB separation and then declined rapidly 30 minutes after SPB separation (Figure 1C and 1D), due to its APC/CCdc20-mediated degradation. Thus, Eco1 levels declined at about the time that Dbf4 reached maximal levels. Note that in the single-cell assay, as in the western blotting results, Eco1 levels dropped gradually relative to the steep decline of the APC/C substrate Dbf4.

High levels of Dbf4 cause DDK to target Eco1 more efficiently

The delay in Eco1 degradation until late S phase could be due to a combination of factors: Dbf4 levels are initially low in early S phase, and DDK could be sequestered by the abundant Mcm double hexamers loaded at licensed origins. To directly test whether Dbf4 is limiting during S phase, we analyzed Eco1 degradation timing in cells overexpressing a stabilized Dbf4 mutant lacking its amino-terminal APC/C recognition sequences (ΔN2-64) [20].

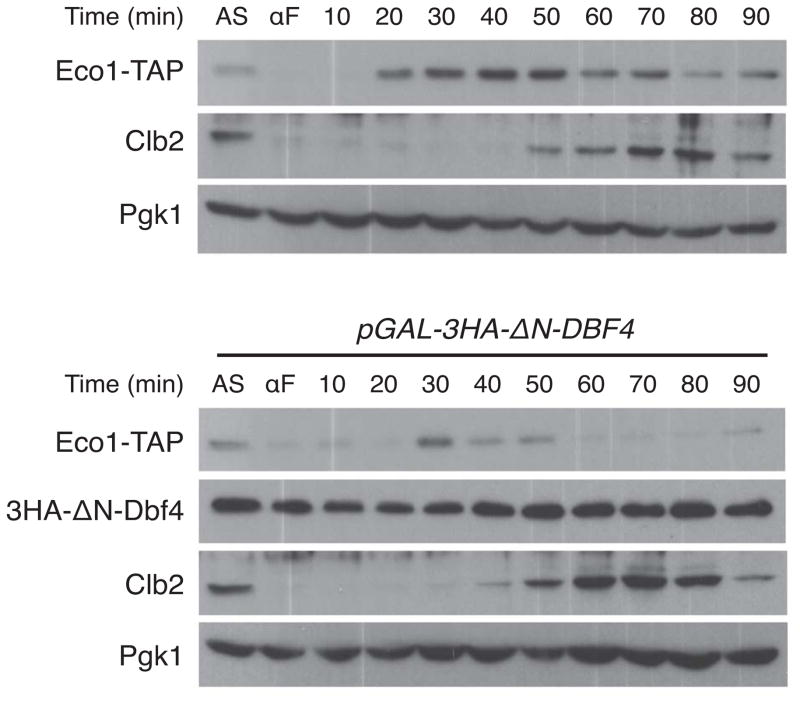

We expressed 3HA-ΔN-DBF4 from the galactose-inducible GAL1 promoter and analyzed Eco1 levels in cells released from a G1 arrest in galactose-containing medium. In wild-type cells, growth in galactose reduced the amount of Eco1 in G1-arrested cells and also delayed cell cycle entry, such that Eco1 levels peaked 40–50 minutes after release (Figure 2, top panel). In cells with overexpressed Dbf4, Eco1 levels were very low and peaked about 30 minutes after release from G1, at about the time of early S phase (Figure 2, bottom panel; Figure S1). Overall, the levels of Eco1 were significantly reduced throughout the cell cycle. These results suggest that phosphorylation of Eco1 is normally restrained by limiting Dbf4 levels in S phase.

Figure 2. Overexpression of Dbf4 causes premature Eco1 degradation.

(Top) A wild-type strain containing Eco1-TAP was grown in galactose-containing medium and arrested in G1 with alpha factor (αF). Following release from G1, cells were sampled at the indicated times for analysis by western blotting. Asynchronous cells (AS) were also analyzed. (Bottom) In parallel, a strain containing 3HA-ΔN-DBF4 under the control of the GAL1 promoter was treated and analyzed as in the top panel. Lysates from the two strains were run on parallel polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose together, and processed together for antibody incubations and film exposure. Results are representative of three separate experiments. Similar results were obtained when samples were run on the same gel (see Figure S1).

Eco1 degradation is not dependent on nuclear export of Mcms or disassembly of the replication complex

Although Dbf4 is limiting for Eco1 phosphorylation during early S phase, there is clearly sufficient kinase activity to target Mcm2-7 complexes at early replication origins. A potential explanation is that the small amount of DDK is docked on loaded Mcm double hexamers at replication origins, thereby preventing DDK from phosphorylating Eco1. It is also possible that DDK interacts with Mcm2-7 complexes that exist in solution. We tested this possibility by measuring the timing of Eco1 degradation in cells with abnormally high levels of Mcm2-7 complexes in the nucleus.

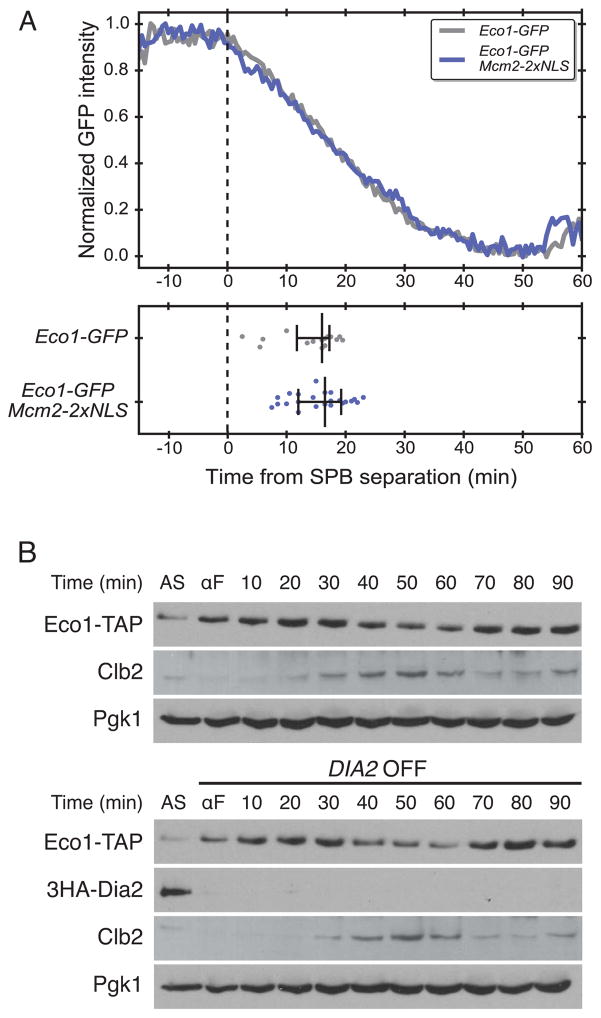

Soluble Mcm2-7 complexes are exported from the nucleus during S phase, greatly reducing their nuclear concentration. To artificially maintain Mcm2-7 complex levels in the nucleus, we used a previously described Mcm2 subunit carrying two extra nuclear localization sequences in its C-terminal region. This mutation makes all Mcm proteins constitutively nuclear throughout S phase [21]. We used fluorescence microscopy to track single cells (as in Figure 1C, D) containing Eco1-GFP with or without the Mcm2-2xNLS mutation. We also analyzed an Mcm2-GFP-2xNLS-expressing strain to verify that this mutant protein remains in the nucleus throughout the cell cycle (data not shown). The timing of Eco1 degradation was not affected by high levels of Mcm2-7 complexes in the nucleus, arguing that high levels of soluble Mcm2-7 complexes do not prevent DDK from targeting Eco1 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Increased Mcm complex in the nucleus or depletion of Dia2 has no impact on Eco1 degradation.

(A) Strains containing Eco1-GFP or Eco1-GFP in an Mcm2-2xNLS background were grown under normal conditions and visualized with a spinning disk confocal microscope as in Figure 1C, D. (Top) Single cell traces were averaged, normalized, and aligned to SPB separation. (Bottom) Each dot represents the time at which the Eco1-GFP signal was reduced by 50% in a single cell. The central bar indicates the median, and error bars indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles (n=13 for Eco1-GFP and n=12 for the Mcm2-2xNLS background). (B) (Top) A wild-type strain containing Eco1-TAP was grown in galactose medium, arrested with alpha factor (αF)and switched to dextrose medium before release from G1. Cells were sampled at the indicated times after release for analysis by western blotting. Asynchronous cells (AS) were also analyzed. (Bottom) Cells containing Eco1-TAP and DIA2 under the control of the GAL1 promoter were arrested in alpha factor and switched to dextrose medium to shut off DIA2 expression before release from G1. Lysates from the two strains were run on parallel polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose together, and processed together for antibody incubations and film exposure. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

We next tested whether Mcm2-7 single hexamers on DNA sequester DDK activity and thereby delay Eco1 phosphorylation. We depleted cells of the F-box protein Dia2, which is required for the disassembly of the replication fork CMG (Cdc45-Mcm-GINS) complex when replication is completed [22, 23]. In the absence of Dia2, Mcm2-7 single hexamers and other CMG components remain associated with chromatin. We found that depletion of Dia2 had no effect on Eco1 levels or degradation timing (Figure 3B). These results suggest that DDK is not sequestered away from Eco1 by interactions with soluble Mcm2-7 or with single hexamers at the replication fork.

Preventing Mcm2-7 loading allows premature Eco1 degradation

Numerous lines of evidence suggest that DDK docks primarily to the double-hexamer Mcm2-7 complex that is loaded at unfired origins of replication, and DDK does not interact productively with Mcm2-7 complexes in solution or with Mcm single hexamers after origin firing [9, 10]. Further evidence [9, 24–29] supports the idea that DDK is targeted to licensed origins by interacting with a compound docking site that is formed by the double Mcm2-7 hexamer. Since the majority of origins in yeast do not fire until the middle of S phase [30], we hypothesized that Eco1 is not phosphorylated until late S phase because DDK is restrained before then by its docking interactions at origins. We tested this hypothesis by disrupting the timing of Mcm complex loading and origin firing.

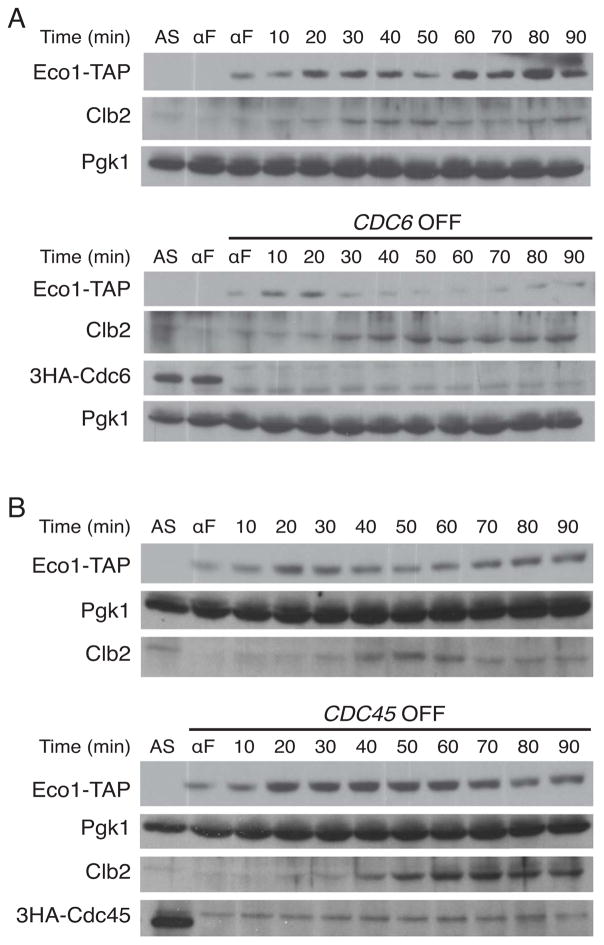

The protein Cdc6 collaborates with the Origin Recognition Complex (ORC) during G1 to load Mcm complexes on origin DNA [31–33]. In the absence of Cdc6, Mcm complexes are not loaded, and the cell enters the cell cycle but fails to initiate DNA replication, eventually arresting in mitosis due to a spindle assembly checkpoint response. We reasoned that the absence of loaded Mcm complexes would prevent sequestration of DDK, allowing it to phosphorylate Eco1 and thereby trigger premature Eco1 degradation. We depleted yeast cells of Cdc6 by placing CDC6 under the control of the GAL1 promoter and shutting off transcription by growth in glucose medium prior to G1 arrest [34, 35]. Strikingly, in cells depleted of Cdc6, Eco1 levels remained very low and peaked early, 20 minutes after G1 release (Figures 4A, S2A). Thus, when the Mcm complex is not loaded at replication origins, DDK is able to target Eco1 upon entry into S phase.

Figure 4. Defects in Mcm complex loading or activation alter the timing of Eco1 degradation.

(A) (Top) A wild-type strain containing Eco1-TAP was arrested with alpha factor (αF) in galactose medium, released for 40 min and then rearrested with alpha factor in dextrose medium. Following release, cells were sampled at the indicated times for analysis by western blotting. Asynchronous cells (AS) were also analyzed. (Bottom) Cells containing CDC6 under the control of the GAL1 promoter were treated and analyzed as in the top panel. (B) (Top) A wild-type strain containing Eco1-TAP was grown in galactose medium, arrested with alpha factor and switched to dextrose medium. Cells were released and sampled at the indicated times for analysis by western blotting. (Bottom) Cells containing CDC45 under the control of the GAL1 promoter were treated and analyzed as in the top panel. In both panels (A) and (B), lysates from the two compared strains were run on parallel polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose together, and processed together for antibody incubations and film exposure. Results are representative of three separate experiments. Similar results were obtained when samples were run on the same gel (see Figures S2 and S3).

We devised a complementary experiment in a strain in which the Mcm complex is loaded but held in the inactive double-hexamer form at origins when the cell enters S phase. If these complexes sequester DDK away from Eco1, then preventing Mcm activation should reduce the rate of Eco1 degradation. For this purpose, we depleted cells of Cdc45, which is required for the recruitment of Sld3, GINS, and ultimately for the firing of origins [36–39]. CDC45 was placed under the control of the GAL1 promoter, and its expression was repressed by growth in glucose medium prior to G1 arrest. Upon release from G1 in cells lacking Cdc45, Eco1 rose to abnormally high levels, and its degradation was greatly delayed (Figures 4B, S2B). These results are consistent with our hypothesis that in wild-type cells, DDK is sequestered during S phase by unfired origins and is therefore unable to target Eco1.

Following depletion of CDC6 or CDC45, Dbf4 levels rose normally and gradually accumulated to high levels, presumably due to the spindle assembly checkpoint response (Figure S2). Thus, abnormal Eco1 levels in these experiments were not the indirect result of changes in the amounts of Dbf4.

Our previous work showed that DNA damage increases Eco1 stability, due to inhibitory Rad53-dependent phosphorylation of Dbf4 [8, 40]. Mutation of the phosphorylation sites (the Dbf4-m25 mutant) prevents Eco1 stabilization by DNA damage. It was therefore possible that Eco1 stabilization in cells lacking Cdc45 was due to DNA damage. However, Eco1 was stabilized following CDC45 shutoff in the dbf4-m25 mutant strain, suggesting that stabilization is not due to a DNA damage response (Figure S3).

Discussion

For a cell to divide successfully, a series of carefully orchestrated events must occur at the correct time and in the correct sequence. The timing of cell-cycle events depends in large part on the timing of phosphorylation of numerous proteins that govern those events. Here we explored the mechanism underlying the unusual late S-phase timing of Eco1 phosphorylation by DDK. Our results argue that sequestration of DDK by unfired replication origins limits DDK activity toward Eco1 until late S phase.

The essential function of Eco1 is to acetylate the cohesin subunit Smc3 during S phase to ensure proper sister-chromatid cohesion [41–43]. Premature Eco1 degradation can cause lethal defects in chromosome segregation, whereas stabilization of Eco1 beyond S phase leads to levels of cohesion that can delay anaphase progression [11]. Thus, there is an optimal S-phase window during which Eco1 must act. However, because Eco1 degradation is triggered by the same kinase that triggers DNA replication, achieving the optimal window of Eco1 function requires a mechanism to keep the kinase away from Eco1 until replication is complete. Our results suggest a possible mechanism.

This mechanism depends on quantitative features of the system. There are several hundred origins of replication in S. cerevisiae [30, 44–48], resulting in several hundred loaded double Mcm hexamers in early S phase. Recent global studies suggest that there are roughly 25 molecules/cell of Dbf4 and 66 molecules/cell of Eco1 [49]. Western blotting also suggests that Dbf4 amounts are far lower than the number of origins [50]. Thus, Mcm double hexamers greatly outnumber DDK complexes. In addition, docking interactions between DDK and the Mcm double hexamer enhance binding and kinase activity [26, 27]. Considering these factors, it seems likely that Dbf4-Cdc7 is occupied primarily with Mcm complexes at unfired origins during S phase. Once S phase nears completion and the number of loaded Mcm double hexamers declines, rising levels of Dbf4 (and DDK activity) would then be free to target Eco1.

Eco1 is thought to interact with the clamp loader PCNA at the replication fork [51]. It is conceivable that this interaction, which depends on a putative PCNA-Interacting-Protein box (PIP box), places Eco1 within range of DDK during early S phase. However, we found that mutation of the PIP box does not affect the timing of Eco1 degradation (data not shown).

Our evidence supports a novel mechanism for timing phosphorylation events at the end of S phase. This cell cycle transition is not governed by a major regulatory switch like those that trigger progression through Start, the G2/M transition, or the metaphase-anaphase transition. This mechanism might provide a way to time the phosphorylation of other DDK targets involved in later cell-cycle functions. There is evidence that DDK activity helps control other cell-cycle processes, including homologous recombination in meiosis [52–54] and rDNA segregation in mitosis [20]. We speculate that the timing of these and other DDK-dependent processes might be governed, at least in part, by the mechanisms we describe.

STAR METHODS

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Peroxidase Anti-Peroxidase (PAP) Soluble Complex Antibody, Rabbit | Sigma | Cat# P1291; RRID: AB_1079562 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-HA (clone 12CA5) | Roche | Cat# 11583816001; RRID: AB_514505 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Pgk1 (clone 22C5D8) | Invitrogen | Cat# 459250 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Clb2 (y-180) | Santa Cruz Biotech | Cat# sc-9071 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-Dbf4 (yN-15) | Santa Cruz Biotech | Cat# sc-5705 |

| Donkey anti-goat HRP-linked secondary antibody | Santa Cruz Biotech | Cat# sc-2020 |

| Sheep anti-mouse HRP-linked secondary antibody | GE Healthcare | Cat# NA931; RRID: AB_772210 |

| Donkey anti-rabbit HRP-linked secondary antibody | GE Healthcare | Cat# NA934; RRID: AB_772206 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Yeast Extract | BD Biosciences | Cat# 212720 |

| Peptone | BD Biosciences | Cat# 211820 |

| Dextrose | US Biological | Cat# G3050 |

| Galactose | US Biological | Cat# G1030 |

| Alpha Factor Peptide | Sigma | Cat# T6901 |

| Concanamycin A | Sigma | Cat# C9705 |

| SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate | ThermoFisher | Cat# 34075 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| WT S288C (BY4741): MATa, his3Δ1, ura3Δ0, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, bar1+ | ATCC | 201388 |

| ECO1-TAP:HIS3 MATa | Lab strain | DOM1091 |

| ECO1-TAP:HIS3 DBF4-6HA:natN2 MATa | This work | AS033 |

| ECO1-TAP:HIS3 natN2:pGAL-3HA-(Δ2-64)DBF4 MATa | This work | AS027 |

| ECO1-GFP:kanMX SPC42-mCHERRY:URA3 MATa | This work | AS030 |

| DBF4-GFP:kanMX SPC42-mCHERRY:URA3 MATa | This work | AS036 |

| ECO1-GFP:kanMX SPC42-mCHERRY:URA3 MCM2-2xNLS:HIS3 MATa | This work | AS037 |

| ECO1-TAP:HIS3 natN2:pGAL-3HA-DIA2 MATa | This work | AS040 |

| ECO1-TAP:HIS3 natN2:pGAL-3HA-CDC6 MATa | This work | AS006 |

| ECO1-TAP:HIS3 natN2:pGAL-3HA-CDC45 MATa | This work | AS020 |

| ECO1-TAP:HIS3 dbf4-m25::LEU2::dbf4Δ::KanMx MATa | Lab strain | DOM1196 |

| ECO1-TAP:HIS3 dbf4-m25::LEU2::dbf4Δ::KanMx natN2:pGAL-3HA-CDC45 MATa | This work | AS029 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for PCR-based gene modification (see Table S1) | This work | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| MATLAB 5.0 | MathWorks | N/A |

| ImageJ 1.7 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ | N/A |

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, David Morgan (david.morgan@ucsf.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

All strains were derivatives of the S288C strain BY4741 and are listed in the Key Resources Table. All strains were constructed by conventional PCR-based homologous recombination techniques [55, 56], using oligonucleotide primers listed in Table S1. For most experiments, cells were grown in Yeast Peptone Dextrose (YPD; 1.0% yeast extract, 2.0% peptone, 2.0% dextrose). For experiments involving galactose-induced gene expression, cells were grown in Yeast Extract Peptone (YEP; 1.0% yeast extract, 2.0% peptone) supplemented with either 2.0% dextrose or 2.0% galactose. For all experiments, cells were grown at 30°C and progressed through a minimum of two doubling times in log phase before any experiments were performed.

METHOD DETAILS

Cell Cycle Time Courses

For cell cycle experiments, cells were arrested in G1 with 15 μg/ml alpha factor (Sigma). Cells grown in the presence of dextrose were arrested for 3 hr, and G1 arrest was verified by light microscopy (>95% shmoo). Cells grown in the presence of galactose were arrested for 4 hr and verified by light microscopy (>95% shmoo). To completely shut off pGAL1-3HA-CDC6 expression, cells were first grown in 2% galactose media and then arrested in alpha factor for 4 hr. Cells were released and after 40 min were harvested and resuspended in 2% dextrose media and alpha factor. After 3 hr, cells were released, and samples were taken every 10 min.

Western blotting

Samples were run on 10% SDS-PAGE gels for 60 min at 180V. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose at 4°C for 60 min at 300 mA. Nitrocellulose was blocked in 5% milk in TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) for 30 min. For detection of Eco1-TAP, membranes were incubated with Peroxidase Anti-Peroxidase complex (PAP) (P1291, Sigma, 1:10,000). Other antigens were detected as indicated with anti-HA (12CA5, Roche, 1:2500), anti-Pgk1 (22C5D8, Invitrogen 1:15,000), anti-Clb2 (y-180, Santa Cruz Biotech, 1:400), or anti-Dbf4 (yN-15, Santa Cruz Biotech, 1:300). Blots were then incubated with secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (GE Healthcare, 1:10,000), except the anti-Dbf4 blot, which was incubated with HRP-linked anti-goat secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech, 1:35,000). West Dura enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (GE Healthcare) was added to each blot for 60 s and wicked off, followed by film exposure in a darkroom.

For time courses in which two strains were compared (Figs 2–4), the two cultures were grown in parallel, and samples from the two strains were analyzed on two polyacrylamide gels run in parallel and transferred to nitrocellulose in the same transfer apparatus. The nitrocellulose was cut into strips for each antigen, and the two strips for each antigen were incubated in the same dish with primary and then secondary antibodies, and then incubated with ECL reagent together and exposed to the same piece of film. For some experiments (Figures S1–S3), samples from two strains were analyzed together on 26-well Criterion TGX Precast Gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories) (15 μl wells), run for 60 min at 180V and transferred to nitrocellulose at 4°C for 60 min at 300 mA.

Fluorescence Microscopy

All images were taken with a spinning-disk confocal microscope at the UCSF Nikon Imaging Center with a 60X/1.4 NA oil immersion objective lens, under the control of μManager [57]. The microscope was an inverted microscope (Ti-E; Nikon) equipped with a scanner unit (CSU-22; Yokogawa) and a camera (Evolve EMCCD; Photometrics). Illumination was provided by a 50-mW, 491-nm laser and a 50-mW, 561-nm laser. Imaging sessions were generally 70 min with 30-s time intervals. Z stacks were taken across 4 μm of distance with 0.5 μm steps for each time point and each channel. Exposure times for mCherry and GFP channels were <75 ms for each z slice. All yeast cultures were grown and imaged at 30°C. Before imaging, yeast cells were grown in synthetic complete media with 2% glucose (SD) for 24 hr with serial dilution to maintain OD <0.4. For imaging, cells were plated onto MatTek 35mm petri dishes (14 mm Microwell) that were pre-treated with 1 mg/ml Concanamycin A. 300 μl of culture was added onto the dish for 5 min and washed twice with 3 ml SD media.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Image Processing

To quantify GFP intensity at each time point, we used ImageJ [58] and its plugin Image5D (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/plugins/image5d.html) to average across each z stack and flatten it to 2D. GFP intensity was then quantified using MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc.) code developed in the Tang laboratory [59]. Because Eco1 is localized to the nucleus, we measured the brightest square of 5×5 pixels in the nucleus as an estimate of the protein concentration. Timing of SPB events was determined based on the temporal 3D positions of the SPB using the mCherry images. SPB separation was defined as the time point when one SPB split into two distinct foci.

Data Processing

The time point of 50% substrate degradation in each cell was defined as when GFP intensity was halfway between the maximum and the minimum intensity on a smoothed trace of a degradation event. Determination of the timing of the 50% drop of GFP signal, or the level of GFP at each time point, was performed with MATLAB code developed by Lu et al. [12]. Statistical analysis and plotting were performed in MATLAB and Python [60, 61].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dan Lu for help with microscopy and data processing and members of the Morgan Lab for valuable discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35GM118053).

Footnotes

Supplemental information includes three figures and can be found with this article online.

Author Contributions

A.I.S. designed and executed the experiments and wrote the paper with guidance from D.O.M.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Godfrey M, Touati SA, Kataria M, Jones A, Snijders AP, Uhlmann F. PP2ACdc55 Phosphatase Imposes Ordered Cell-Cycle Phosphorylation by Opposing Threonine Phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2017;65:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamenz J, Ferrell JE., Jr The Temporal Ordering of Cell-Cycle Phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2017;65:371–373. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loog M, Morgan DO. Cyclin specificity in the phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinase substrates. Nature. 2005;434:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature03329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swaffer MP, Jones AW, Flynn HR, Snijders AP, Nurse P. CDK Substrate Phosphorylation and Ordering the Cell Cycle. Cell. 2016;167:1750–1761. e1716. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell SP, Labib K. Chromosome Duplication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2016;203:1027–1067. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.186452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bousset K, Diffley JF. The Cdc7 protein kinase is required for origin firing during S phase. Genes Dev. 1998;12:480–490. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donaldson AD, Fangman WL, Brewer BJ. Cdc7 is required throughout the yeast S phase to activate replication origins. Genes Dev. 1998;12:491–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyons NA, Fonslow BR, Diedrich JK, Yates JR, 3rd, Morgan DO. Sequential primed kinases create a damage-responsive phosphodegron on Eco1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:194–201. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francis LI, Randell JC, Takara TJ, Uchima L, Bell SP. Incorporation into the prereplicative complex activates the Mcm2-7 helicase for Cdc7-Dbf4 phosphorylation. Genes Dev. 2009;23:643–654. doi: 10.1101/gad.1759609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun J, Fernandez-Cid A, Riera A, Tognetti S, Yuan Z, Stillman B, Speck C, Li H. Structural and mechanistic insights into Mcm2-7 double-hexamer assembly and function. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2291–2303. doi: 10.1101/gad.242313.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons NA, Morgan DO. Cdk1-dependent destruction of Eco1 prevents cohesion establishment after S phase. Mol Cell. 2011;42:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu D, Hsiao JY, Davey NE, Van Voorhis VA, Foster SA, Tang C, Morgan DO. Multiple mechanisms determine the order of APC/C substrate degradation in mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2014;207:23–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201402041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iizuka R, Yamagishi-Shirasaki M, Funatsu T. Kinetic study of de novo chromophore maturation of fluorescent proteins. Anal Biochem. 2011;414:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khmelinskii A, Keller PJ, Bartosik A, Meurer M, Barry JD, Mardin BR, Kaufmann A, Trautmann S, Wachsmuth M, Pereira G, et al. Tandem fluorescent protein timers for in vivo analysis of protein dynamics. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:708–714. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson CG, Maddox PS, Salmon ED, Bloom K. Budding yeast chromosome structure and dynamics during mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1255–1266. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Straight AF, Marshall WF, Sedat JW, Murray AW. Mitosis in living budding yeast: anaphase A but no metaphase plate. Science. 1997;277:574–578. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yaakov G, Thorn K, Morgan DO. Separase biosensor reveals that cohesin cleavage timing depends on phosphatase PP2A(Cdc55) regulation. Dev Cell. 2012;23:124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byers B, Goetsch L. Behavior of spindles and spindle plaques in the cell cycle and conjugation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1975;124:511–523. doi: 10.1128/jb.124.1.511-523.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim HH, Loy CJ, Zaman S, Surana U. Dephosphorylation of threonine 169 of Cdc28 is not required for exit from mitosis but may be necessary for start in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4573–4583. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan M, Holt L, Morgan DO. Cyclin-specific control of ribosomal DNA segregation. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5328–5336. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00235-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen VQ, Co C, Irie K, Li JJ. Clb/Cdc28 kinases promote nuclear export of the replication initiator proteins Mcm2-7. Curr Biol. 2000;10:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lengronne A, Pasero P. Closing the MCM cycle at replication termination sites. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1226–1227. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maric M, Maculins T, De Piccoli G, Labib K. Cdc48 and a ubiquitin ligase drive disassembly of the CMG helicase at the end of DNA replication. Science. 2014;346:1253596. doi: 10.1126/science.1253596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dowell SJ, Romanowski P, Diffley JF. Interaction of Dbf4, the Cdc7 protein kinase regulatory subunit, with yeast replication origins in vivo. Science. 1994;265:1243–1246. doi: 10.1126/science.8066465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncker BP, Shimada K, Tsai-Pflugfelder M, Pasero P, Gasser SM. An N-terminal domain of Dbf4p mediates interaction with both origin recognition complex (ORC) and Rad53p and can deregulate late origin firing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16087–16092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252093999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramer MD, Suman ES, Richter H, Stanger K, Spranger M, Bieberstein N, Duncker BP. Dbf4 and Cdc7 proteins promote DNA replication through interactions with distinct Mcm2-7 protein subunits. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:14926–14935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.392910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheu YJ, Stillman B. Cdc7-Dbf4 phosphorylates MCM proteins via a docking site-mediated mechanism to promote S phase progression. Mol Cell. 2006;24:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheu YJ, Stillman B. The Dbf4-Cdc7 kinase promotes S phase by alleviating an inhibitory activity in Mcm4. Nature. 2010;463:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature08647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinreich M, Stillman B. Cdc7p-Dbf4p kinase binds to chromatin during S phase and is regulated by both the APC and the RAD53 checkpoint pathway. EMBO J. 1999;18:5334–5346. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raghuraman MK, Winzeler EA, Collingwood D, Hunt S, Wodicka L, Conway A, Lockhart DJ, Davis RW, Brewer BJ, Fangman WL. Replication dynamics of the yeast genome. Science. 2001;294:115–121. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5540.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cocker JH, Piatti S, Santocanale C, Nasmyth K, Diffley JF. An essential role for the Cdc6 protein in forming the pre-replicative complexes of budding yeast. Nature. 1996;379:180–182. doi: 10.1038/379180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang C, Weinreich M, Stillman B. ORC and Cdc6p interact and determine the frequency of initiation of DNA replication in the genome. Cell. 1995;81:667–676. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka T, Knapp D, Nasmyth K. Loading of an Mcm protein onto DNA replication origins is regulated by Cdc6p and CDKs. Cell. 1997;90:649–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biggins S, Murray AW. The budding yeast protein kinase Ipl1/Aurora allows the absence of tension to activate the spindle checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3118–3129. doi: 10.1101/gad.934801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piatti S, Bohm T, Cocker JH, Diffley JF, Nasmyth K. Activation of S-phase-promoting CDKs in late G1 defines a “point of no return” after which Cdc6 synthesis cannot promote DNA replication in yeast. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1516–1531. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hopwood B, Dalton S. Cdc45p assembles into a complex with Cdc46p/Mcm5p, is required for minichromosome maintenance, and is essential for chromosomal DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12309–12314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamimura Y, Tak YS, Sugino A, Araki H. Sld3, which interacts with Cdc45 (Sld4), functions for chromosomal DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2001;20:2097–2107. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owens JC, Detweiler CS, Li JJ. CDC45 is required in conjunction with CDC7/DBF4 to trigger the initiation of DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12521–12526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zou L, Mitchell J, Stillman B. CDC45, a novel yeast gene that functions with the origin recognition complex and Mcm proteins in initiation of DNA replication. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:553–563. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez-Mosqueda J, Maas NL, Jonsson ZO, Defazio-Eli LG, Wohlschlegel J, Toczyski DP. Damage-induced phosphorylation of Sld3 is important to block late origin firing. Nature. 2010;467:479–483. doi: 10.1038/nature09377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rolef Ben-Shahar T, Heeger S, Lehane C, East P, Flynn H, Skehel M, Uhlmann F. Eco1-dependent cohesin acetylation during establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2008;321:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.1157774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unal E, Heidinger-Pauli JM, Kim W, Guacci V, Onn I, Gygi SP, Koshland DE. A molecular determinant for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2008;321:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.1157880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Shi X, Li Y, Kim BJ, Jia J, Huang Z, Yang T, Fu X, Jung SY, Wang Y, et al. Acetylation of Smc3 by Eco1 is required for S phase sister chromatid cohesion in both human and yeast. Mol Cell. 2008;31:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng W, Collingwood D, Boeck ME, Fox LA, Alvino GM, Fangman WL, Raghuraman MK, Brewer BJ. Genomic mapping of single-stranded DNA in hydroxyurea-challenged yeasts identifies origins of replication. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:148–155. doi: 10.1038/ncb1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nieduszynski CA, Knox Y, Donaldson AD. Genome-wide identification of replication origins in yeast by comparative genomics. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1874–1879. doi: 10.1101/gad.385306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wyrick JJ, Aparicio JG, Chen T, Barnett JD, Jennings EG, Young RA, Bell SP, Aparicio OM. Genome-wide distribution of ORC and MCM proteins in S. cerevisiae: high-resolution mapping of replication origins. Science. 2001;294:2357–2360. doi: 10.1126/science.1066101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu W, Aparicio JG, Aparicio OM, Tavare S. Genome-wide mapping of ORC and Mcm2p binding sites on tiling arrays and identification of essential ARS consensus sequences in S. cerevisiae. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:276. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yabuki N, Terashima H, Kitada K. Mapping of early firing origins on a replication profile of budding yeast. Genes Cells. 2002;7:781–789. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kulak NA, Pichler G, Paron I, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Minimal, encapsulated proteomic-sample processing applied to copy-number estimation in eukaryotic cells. Nat Methods. 2014;11:319–324. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mantiero D, Mackenzie A, Donaldson A, Zegerman P. Limiting replication initiation factors execute the temporal programme of origin firing in budding yeast. EMBO J. 2011;30:4805–4814. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moldovan GL, Pfander B, Jentsch S. PCNA controls establishment of sister chromatid cohesion during S phase. Mol Cell. 2006;23:723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murakami H, Keeney S. Temporospatial coordination of meiotic DNA replication and recombination via DDK recruitment to replisomes. Cell. 2014;158:861–873. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sasanuma H, Hirota K, Fukuda T, Kakusho N, Kugou K, Kawasaki Y, Shibata T, Masai H, Ohta K. Cdc7-dependent phosphorylation of Mer2 facilitates initiation of yeast meiotic recombination. Genes Dev. 2008;22:398–410. doi: 10.1101/gad.1626608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wan L, Niu H, Futcher B, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Boulton SJ, Hollingsworth NM. Cdc28-Clb5 (CDK-S) and Cdc7-Dbf4 (DDK) collaborate to initiate meiotic recombination in yeast. Genes Dev. 2008;22:386–397. doi: 10.1101/gad.1626408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Janke C, Magiera MM, Rathfelder N, Taxis C, Reber S, Maekawa H, Moreno-Borchart A, Doenges G, Schwob E, Schiebel E, et al. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast. 2004;21:947–962. doi: 10.1002/yea.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Longtine MS, McKenzie A, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edelstein A, Amodaj N, Hoover K, Vale R, Stuurman N. Computer control of microscopes using microManager. Current protocols in molecular biology / edited by Frederick M. Ausubel … [et al.] 2010;Chapter 14(Unit14):20. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1420s92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang X, Lau KY, Sevim V, Tang C. Design principles of the yeast G1/S switch. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hunter JD. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput Sci Eng. 2007;9:90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oliphant TE. Python for scientific computing. Comput Sci Eng. 2007;9:10–20. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.