Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) in children is frequently associated with a translocation in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene at the 2p23 locus. In ALK-positive ALCL (ALK+ ALCL), the major fusion partner is nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1), which results in the translocation t(2;5)(p23;q35) and aberrant production of the 80-kDa fusion protein NPM1–ALK.1 ALK kinase belongs to the insulin receptor subfamily of kinases and is expressed in only the neuronal tissue, ganglion cells of the intestine, and testis. However, translocation with NPM1 or alternative partners leads to aberrant constitutive activation of the catalytic domain of ALK through homodimerization.2 For the most common NPM1–ALK fusion, immunohistochemical detection of the ALK antigen shows both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining due to the heterodimerization of NPM1–ALK and normal NPM1, a nucleolar phosphoprotein that is ubiquitously expressed and shuttles between the cytoplasm and the nucleus.3 Approximately 15% of ALK+ ALCL cases lack the nuclear staining pattern, indicating that aberrant ALK expression is due to a partner gene other than NPM1. Indeed, in some ALK+ ALCL cases, a different partner for ALK has been identified, such as TMP3, TFG, ATIC, CLTCL, MSN, MYH9, or TRAF.4, 5 Herein, we report a novel translocation partner for ALK in 2 pediatric patients with ALCL by using next-generation transcriptome sequencing analysis.

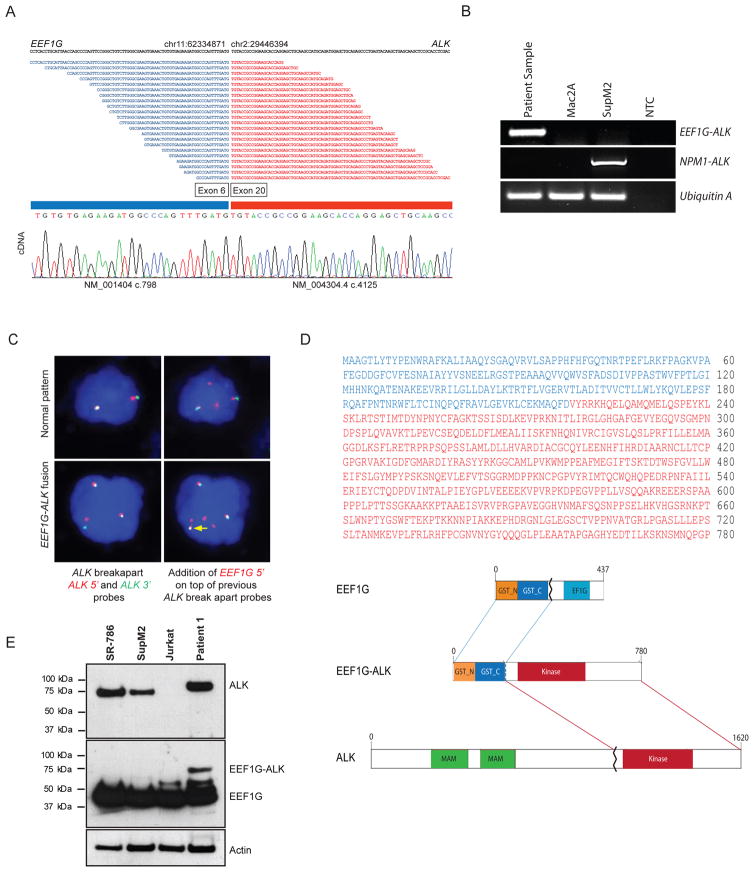

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was used to identify the non-NPM1 partner of the ALK fusion in a case of ALK+ ALCL (patient 1) that exhibited a cytoplasmic-only ALK staining pattern (Supplementary Figure S1). RNA-seq analysis of the tumor revealed 106 fragments representing a chimeric in-frame fusion that juxtaposed exon 6 of the eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1, gamma (EEF1G) to exon 20 of ALK (Figure 1A, upper panel). Reverse-transcription PCR confirmed the presence of EEF1G–ALK transcripts in the tumor sample but not in the NPM1-ALK–positive ALCL cell line SupM2 (Figure 1B). Sanger sequencing verified that the fusion occurred at EEF1G NM_001404 c.798 (exon 6) and ALK NM_004304 c.4125 (exon 20) (Figure 1A, lower panel). The same ALK breakpoint corresponding to exon 20 has been reported in other ALK fusions in ALCL.6–8 To map the genomic breakpoints, a conventional PCR-based assay was performed by using a series of forward primers designed to start from exon 20 through intron 20 of ALK (negative strand) and reverse primers to start from the C-terminal part of exon 6 through intron 7 of EEF1G (negative strand). Bidirectional Sanger sequencing of the PCR product revealed a breakpoint at position chr11: 62567064 within EEF1G and chr2: 29223806 within ALK (Supplementary Figure S2). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) of primary tumor sections confirmed the presence of the EEF1G–ALK rearrangement (Figure 1C). These results verify that EEF1G is a novel partner of ALK in ALCL, which results in the translocation t(2;11)(2p23;11q12.3). Mutation or rearrangement of EEF1G has not been previously reported in congenital or acquired disorders.

Figure 1. Identification and molecular characterization of the EEF1G–ALK fusion gene in ALCL.

(A) RNA-seq data illustrating the forward-fragment reads overlapping the junction breakpoint between the 5′ EEF1G component and the 3′ ALK component (top), which was verified by Sanger sequencing (bottom). At the junction, EEF1G exon 6 and ALK exon 20 reading frames were conserved. (B) PCR of cDNA prepared from the RNA tumor sample used for RNA-seq revealed a 221-bp amplicon corresponding to the region harboring the EEF1G–ALK fusion site in the sample from patient 1 but not in cDNA from SupM2 (containing the NPM1–ALK fusion) or Mac2A (ALK-negative) cell lines. A sample lacking the cDNA template was the non-template control (NTC). PCR reactions were performed on the same samples used to amplify the NPM1–ALK fusion. Ubiquitin A was the positive loading control. (C) The ALK breakapart assay revealed either the normal gene (tightly linked red and green signals) or disrupted ALK (widely spaced red and green signals). Hybridization of 5′ EEF1G (red signal) on top of the previous ALK breakpoint shows pairing with the disrupted 3′ ALK probe, indicating the presence of the EEF1G–ALK fusion gene. (D) Amino acid sequence of the EEF1G-ALK protein (upper panel). Residues corresponding to EEF1G and ALK are shown in blue and red, respectively. Protein domain diagrams illustrating preservation of the N-terminal GST domains of EEF1G and the C-terminal tyrosine kinase domain of ALK in the EEF1G–ALK fusion protein (lowe panel). (E) Western blot assays for ALK and EEF1G using the tumor sample from patient 1 and ALCL cell lines SR-786, SupM2, and Jurkat. SupM2 and SR-786 harbored the NPM1–ALK fusions (80 kDa). The native EEF1G had a molecular mass of 50 kDa. In the patient sample, a discrete band with a molecular mass slightly more than 80 kDa as a result of the EEF1G-ALK fusion was seen (concurrently run protein standards indicated by lines).

To assess the frequency of the novel EEF1G–ALK fusion gene in ALK+ ALCL, RNA-seq data from 27 additional pediatric patients with ALCL were studied to determine the presence of the ALK fusion. In this group that also included patient 1 described above (n = 28), all patients harbored an ALK fusion, of whom 4 (14.3%) had a variant non–NPM1-ALK fusion. The identified partner genes included the novel ALK partner EEF1G in 1 more case (patient 2) and the known partner ATIC (2q35) in 2 patients. Immunohistochemical staining for ALK expression in tumor tissues from these 4 patients revealed a cytoplasmic-only ALK staining pattern, which was consistent with the presence of a variant t(2p23/ALK) (Supplementary Figure S1). Wild-type or full-length ALK mRNA was not detected.

As seen for patient 1, RNA-seq analysis of the tumor from patient 2 revealed the same chimeric in-frame fusion that juxtaposed exon 6 of EEF1G to exon 20 of ALK. FISH analysis of tumor section from patient 2 confirmed the presence of the EEF1G–ALK fusion (73% of the cells counted). A subset of the tumor cells (33%) showed one extra copy of the rearranged ALK gene, which was not observed on patient 1 by FISH. PCR analysis of genomic DNA from patient 2 showed presence of the EEF1G–ALK fusion. Sanger sequencing revealed breakpoints in the same introns within the EEF1G (intron 7) and the ALK (intron 20) genes (Supplementary Figure S2).

The EEF1G–ALK fusion encodes a 780-amino-acid chimeric protein with a predicted molecular mass of 87 kDa (Figure 1D). The novel EEF1G–ALK fusion is predicted to yield a protein product comprising the N-terminal GST-like domain of EEF1G (residues 1-225) and the cytoplasmic tail containing the tyrosine kinase domain of ALK (resides 226-780) (Figure 1D). In patient 1, Western blot analysis for both ALK and total EEF1G revealed a band corresponding to a molecular mass slightly higher than that for the 80-kDa NPM1–ALK present in the ALK+ ALCL cell lines SR-786 and SupM2, which was consistent with expression of the novel fusion (Figure 1E).

EEF1G, located on chromosome 11q12.3, encodes a member of the eukaryotic elongation factor-1 (EF1) complex that controls the elongation phase of protein synthesis. The eEF1 complex comprises subunits EEF1A, EEF1Bα or EEF1-beta (EEF1B), EEF1Bβ or EEF1-delta (EEF1D), and EEF1Bγ or EEF1-gamma (EEF1G).9 The N-terminal domain of EEF1G is structurally similar to the theta class of glutathione S-transferase (GST).10, 11 Purification of the recombinant full-length amino- and carboxy-terminal domains of the human EEF1G protein showed that the full-length and amino-terminal domains are dimeric whereas the C-terminal domain is monomeric.11 Structural studies of the yeast EF-1 complex indicate that the GST-like domain of EEF1G is essential for the stable dimerization of EEF1G and the quaternary structure of the EF-1 complex.12, 13 In the EEF1G–ALK fusion reported herein, the 5′ partner of the fusion protein retained the GST domain of EEF1G (Figure 1B).

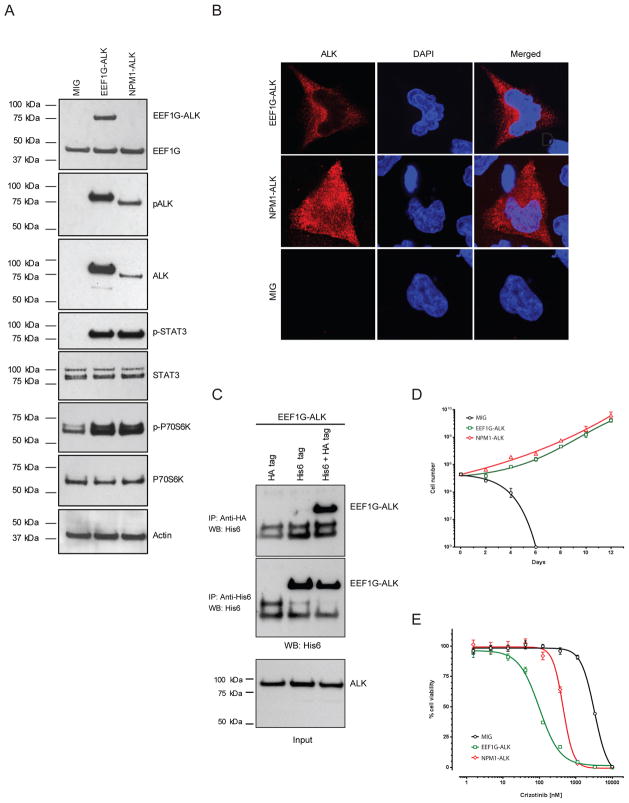

Ectopic expression of the full-length EEF1G–ALK coding sequence in HEK293T cells, followed by Western blot analysis of both EEF1G and total ALK, confirmed expression of the EEF1G–ALK fusion protein, which had a predicted size of approximately 87 kDa (Figure 2A). Also, phospho-ALK levels were high in the EEF1G-ALK–transfected HEK293T cells, indicating a constitutively active EEF1G–ALK tyrosine kinase (Figure 2A). Consistent with this finding, expression of EEF1G–ALK induced the activation/phosphorylation of both STAT3 and P70S6K (Figure 2A, Supplementary Figure S3). Further, the EEF1G–ALK fusion demonstrated anti-ALK staining that was restricted to the cytoplasm, in contrast to the cytoplasmic and nuclear staining observed in NPM1-ALK–positive ALCL. Studies in human fibroblasts indicate that 3 subunits of the EF-1 complex, EEF1B, EEF1G, and EEF1D, colocalize in the cytoplasm with the endoplasmic reticulum, possibly via EEF1G.14, 15 Subcellular protein localization studies of the EEF1G–ALK fusion in HeLa cells showed a cytoplasmic-only localization, consistent with the histologic observation in the tumor sample and the expected localization directed by the EEF1G partner gene (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Functional characterization of the EEF1G–ALK fusion gene.

(A) Ectopic expression of the EEF1G–ALK fusion protein in HEK 293T cells assessed by Western blotting shows phosphorylation of the approximately 87-kDa EEF1G–ALK and 80-kDa NPM1–ALK chimeric proteins, which are associated with phosphorylation of the known downstream targets of ALK, STAT3, and P70S6K. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy of HeLa cells transiently transfected with expression vectors harboring EEF1G–ALK, NPM1–ALK, or empty vector (MIG) and stained with ALK monoclonal antibody. Subcellular localization of the expressed fusion protein, as indicated by the red fluorescence, shows the presence of EEF1G–ALK in only the cytoplasm, whereas NPM1–ALK is found in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. DAPI staining was performed to identify the nuclei. (C) Expression vectors for HA-tagged EEF1G–ALK and His-tagged EEF1G–ALK were introduced into HEK293T cells together or singly. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to HA or His6, and the precipitates were immunoblotted with anti-His6 antibody. The position of EEF1G–ALK is shown on the right (arrows). The arrow heads indicate nonspecific bands. (D) EEF1G–ALK confers cytokine-independent growth to Ba/F3 cells. Stably transduced Ba/F3 cells expressing EEF1G–ALK (Supplementary Figure S3) were assessed for growth in the absence of IL-3, along with NPM1–ALK and empty vector–transduced cells. Viable cell counts were determined in quadruplicate, using trypan blue at 48-h intervals; each timepoint represents the mean ± SEM. (E) Cytokine-independent proliferation was inhibited by the small-molecule ALK inhibitor crizotinib. Transduced Ba/F3 cells were grown in increasing concentrations of crizotinib. Results represent the mean ± SEM from quadruplicate determinations.

Because the signaling by ALK fusion proteins depends on a dimerization site in the fusion partner, it is possible that the GST domain derived from EEF1G mediates the dimerization and activation of EEF1G–ALK. As point mutations are a potential mechanism for aberrant kinase activation, we studied RNA-seq data to confirm that the tumor did not harbor mutations within the ALK kinase domain. To verify the dimerization potential of EEF1G, we transfected HEK293T cells with expression vectors for both hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged EEF1G–ALK and hexahistidine (His6)–tagged EEF1G–ALK. Immunoprecipitation of cell lysates with antibodies to HA and probing of the resultant precipitates with antibodies to His6 revealed that HA-tagged EEF1G–ALK was associated with substantial amounts of the His6-tagged EEF1G–ALK (Figure 2C). Immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitates with antibodies to His6 confirmed that the His6-tagged EEF1G–ALK under the 2 different transfection conditions was expressed at similar levels. These results support the dimerization properties of the novel EEF1G–ALK fusion.

To further assess the oncogenic potential of the EEF1G–ALK fusion, cell proliferation assays of murine Ba/F3 cells expressing EEF1G–ALK were performed in the absence of exogenous cytokines. EEF1G–ALK expression conferred cytokine-independent growth (Figure 2D) similar to that observed in Ba/F3 cells expressing the NPM1–ALK fusion protein. Importantly, crizotinib, a small-molecule inhibitor of ALK, reduced the cytokine-independent proliferation of transduced Ba/F3 cells (Figure 2E). Consistent with this observation, immunoblot analysis revealed that crizotinib inhibited the phosphorylation of tyrosine on EEF1G–ALK (on the residue corresponding to the phosphorylated Tyr 1282/1283 residues of wild-type ALK) in a concentration-dependent manner in transfected Ba/F3 cells (Supplementary Figure S3). These findings support that, as seen in the NPM1–ALK fusion, the novel EEF1G–ALK fusion also exhibits a cell-transforming activity that is dependent on activation of ALK kinase.

In conclusion, we describe a novel EEF1G–ALK gene fusion in 2 pediatric patients with ALCL that is associated with a cytoplasmic-restricted localization of the ALK fusion protein. Our functional studies provide support for the dimerization properties of the EEF1G–ALK chimeric protein and constitutive activation of ALK kinase, which promotes cell proliferation independently of the nuclear localization of the ALK fusion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Children’s Oncology Group and the Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group (CCLG) Tissue Bank for access to specimens. The CCLG Tissue Bank is funded by Cancer Research UK and CCLG. This work was supported in part by ALSAC and by the National Cancer Institute Grant CA21765 (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Cancer Center Support Grant). We thank the staff of the Hartwell Center for Bioinformatics and Biotechnology, the Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core Facility, and the Cell and Tissue Imaging Facility at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

GP performed the experiments and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; TS and YL interpreted RNA-seq data; RKS, CGM, and MSL contributed to reagent preparation and assisted in preparation of the manuscript; JTS assisted with the writing of the paper; MV performed and analyzed FISH data; and VL designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Morris SW, Kirstein MN, Valentine MB, Dittmer KG, Shapiro DN, Saltman DL, et al. Fusion of a kinase gene, ALK, to a nucleolar protein gene, NPM, in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Science. 1994 Mar 4;263(5151):1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.8122112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bischof D, Pulford K, Mason DY, Morris SW. Role of the nucleophosmin (NPM) portion of the non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma-associated NPM-anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion protein in oncogenesis. Molecular and cellular biology. 1997 Apr;17(4):2312–2325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan WY, Liu QR, Borjigin J, Busch H, Rennert OM, Tease LA, et al. Characterization of the cDNA encoding human nucleophosmin and studies of its role in normal and abnormal growth. Biochemistry. 1989 Feb 7;28(3):1033–1039. doi: 10.1021/bi00429a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallberg B, Palmer RH. Mechanistic insight into ALK receptor tyrosine kinase in human cancer biology. Nature reviews Cancer. 2013 Oct;13(10):685–700. doi: 10.1038/nrc3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein H, Foss HD, Durkop H, Marafioti T, Delsol G, Pulford K, et al. CD30(+) anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a review of its histopathologic, genetic, and clinical features. Blood. 2000 Dec 1;96(12):3681–3695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman AL, Vasmatzis G, Asmann YW, Davila J, Middha S, Eckloff BW, et al. Novel TRAF1-ALK fusion identified by deep RNA sequencing of anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013 Nov;52(11):1097–1102. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamant L, Dastugue N, Pulford K, Delsol G, Mariame B. A new fusion gene TPM3-ALK in anaplastic large cell lymphoma created by a (1;2)(q25;p23) translocation. Blood. 1999 May 1;93(9):3088–3095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trinei M, Lanfrancone L, Campo E, Pulford K, Mason DY, Pelicci PG, et al. A new variant anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-fusion protein (ATIC-ALK) in a case of ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2000 Feb 15;60(4):793–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasikumar AN, Perez WB, Kinzy TG. The many roles of the eukaryotic elongation factor 1 complex. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2012 Jul-Aug;3(4):543–555. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koonin EV, Mushegian AR, Tatusov RL, Altschul SF, Bryant SH, Bork P, et al. Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 gamma contains a glutathione transferase domain--study of a diverse, ancient protein superfamily using motif search and structural modeling. Protein Sci. 1994 Nov;3(11):2045–2054. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Achilonu I, Siganunu TP, Dirr HW. Purification and characterisation of recombinant human eukaryotic elongation factor 1 gamma. Protein expression and purification. 2014 Jul;99:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeppesen MG, Ortiz P, Shepard W, Kinzy TG, Nyborg J, Andersen GR. The crystal structure of the glutathione S-transferase-like domain of elongation factor 1Bgamma from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003 Nov 21;278(47):47190–47198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Damme H, Amons R, Janssen G, Moller W. Mapping the functional domains of the eukaryotic elongation factor 1 beta gamma. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1991 Apr 23;197(2):505–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen GM, Moller W. Elongation factor 1 beta gamma from Artemia. Purification and properties of its subunits. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1988 Jan 15;171(1–2):119–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders J, Brandsma M, Janssen GM, Dijk J, Moller W. Immunofluorescence studies of human fibroblasts demonstrate the presence of the complex of elongation factor-1 beta gamma delta in the endoplasmic reticulum. Journal of cell science. 1996 May;109( Pt 5):1113–1117. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.