Abstract

Supporting the health of growing numbers of frail older adults living in subsidized housing requires interventions that can combat frailty, improve residents’ functional abilities, and reduce their health care costs. Tai Chi is an increasingly popular multimodal mind–body exercise that incorporates physical, cognitive, social, and meditative components in the same activity and offers a promising intervention for ameliorating many of the conditions that lead to poor health and excessive health care utilization. The Mind Body-Wellness in Supportive Housing (Mi-WiSH) study is an ongoing two-arm cluster randomized, attention-controlled trial designed to examine the impact of Tai Chi on functional indicators of health and health care utilization. We are enrolling participants from 16 urban subsidized housing facilities (n=320 participants), conducting the Tai Chi intervention or education classes and social calls (attention control) in consenting subjects within the facilities for one year, and assessing these subjects at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year. Physical function (quantified by the Short Physical Performance Battery), and health care utilization (emergency visits, hospitalizations, skilled nursing and nursing home admissions), assessed at 12 months are co-primary outcomes. Our discussion highlights our strategy to balance pragmatic and explanatory features into the study design, describes efforts to enhance site recruitment and participant adherence, and summarizes our broader goal of post study dissemination if effectiveness and cost-effectiveness are demonstrated, by preparing training and protocol manuals for use in housing facilities across the U.S.

Keywords: Frailty, aging, subsidized housing, mind-body exercise, health care utilization

Introduction

The rapid growth of the United States population over age 80 expected over the next 20 years will create enormous challenges for our health care system.[1] Many of these elderly individuals will develop physical and cognitive disabilities that will make independent living difficult.[2] Moreover, as a result of their medical needs, loss of income, and limited pensions, many will be poor and dependent on government support for housing and health care. Currently, approximately 15% of seniors or 3.5 million people in the US live at or below the poverty level.[3] Many of these people are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid and live in Federal or State subsidized supportive housing facilities. Dual-eligible beneficiaries are generally poor and frail with worse health status than other Medicare beneficiaries. They tend to use more health care services and account for a disproportionate share of Medicare spending, particularly for inpatient hospitalizations.[4] Older adults living in public housing are twice as likely — 57 percent vs. 27 percent — to report fair or poor health compared to those with no public housing experience.[5]

Given the large and growing problem of supporting the health and health care needs of frail seniors living in subsidized housing, it is particularly important to identify interventions that can combat frailty, improve residents’ functional abilities, and ultimately reduce their health care costs. Tai Chi is an increasingly popular multimodal mind–body exercise that incorporates physical, cognitive, social, and meditative components in the same activity and offers a promising intervention for ameliorating many of the conditions that lead to poor health and excessive health care utilization. Studies have shown that Tai Chi exercise can improve a number of medical conditions relevant to frail elders, including chronic heart failure, [6–9] hypertension, [10–12] hyperlipidemia, [10, 13, 14] coronary artery disease, [15–18] chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, [19–21] cardiorespiratory fitness, [22–24] poor balance, [25–28] reduced musculoskeletal strength and flexibility, [13, 22, 29–31] Parkinson’s disease, [32] rheumatologic conditions, [33–37] cognitive decline, [38, 39] and overall mood.[40] In a previous pilot study, we have shown that Tai Chi can be practiced successfully and without adverse effects by frail seniors living in supportive housing and results in significant improvements in balance, gait, and functional ability after only 12 weeks.[41] However, it remains to be determined whether a longer period of Tai Chi exercise can further improve the health of poor, frail seniors and reduce their health care utilization and costs. The Mind Body-Wellness in Supportive Housing (Mi-WiSH) study is a cluster randomized, attention-controlled trial designed to address this evidence gap. Mi-WiSH examines traditional physiological and functional indicators of health and ultimate health care utilization and costs as outcomes of a year-long Tai Chi intervention.

Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Aims and Hypotheses

The Mi-WISH study is a cluster randomized, attention controlled trial of twice-weekly Tai Chi classes with interim video reinforcement compared to health promotion educational classes and monthly social calls for 1 year in low-income elderly housing facilities in multiple communities within the Greater Boston area, Massachusetts, USA. We are enrolling participants from 16 facilities over two 1-year periods, conducting the Tai Chi intervention or education classes and social calls (attention control) in consenting subjects expected to remain within the same facility for one year, and assessing these subjects at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year. Physical function and health care utilization assessed at 12 months are co-primary outcomes. The study has the following two Specific Aims and associated hypotheses:

Specific Aim 1

To determine the effects of the Tai Chi intervention on functional performance over a one-year period in poor, multiethnic, and functionally-limited elderly residents of subsidized housing facilities. The primary functional outcome is overall physical function as quantified by the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). Secondary outcomes include specific aspects of physical function, cognition, psychological well-being, falls, exercise self-efficacy, and satisfaction with the intervention. We hypothesize that participation in the Tai Chi classes will improve outcomes within each of these domains as compared to educational classes and monthly social calls.

Specific Aim 2

To determine the effects of the Tai Chi intervention on health care utilization during the one-year periods during Tai Chi or educational classes in poor, multiethnic, functionally-limited elderly residents of subsidized housing facilities. The primary utilization outcomes will be emergency visits, hospitalizations, and nursing home admission. We hypothesize that compared to the control intervention, the Tai Chi intervention will significantly reduce health care utilization during the intervention period.

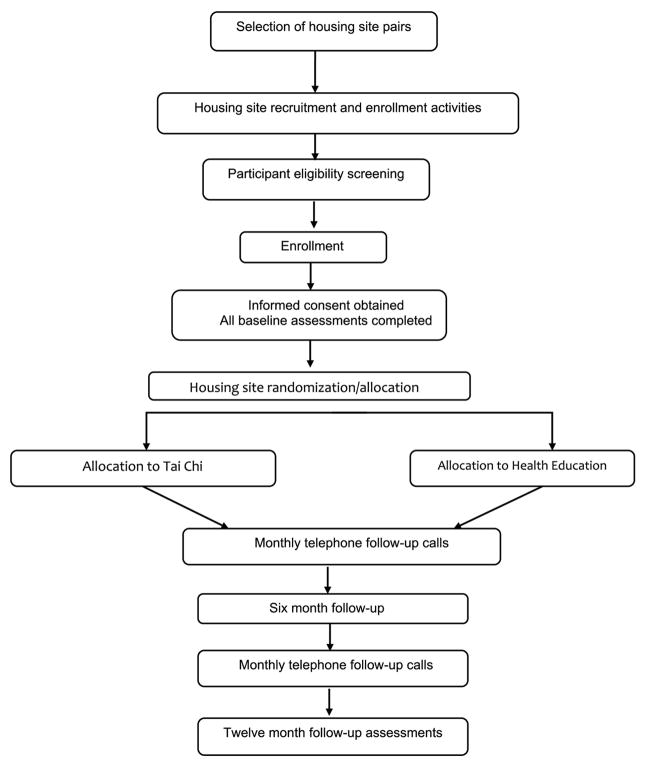

Figure 1 shows the study schema.

Figure 1.

MiWish Study Schema

2.2. Ethical Oversight

The study is approved and monitored by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Hebrew Senior Life. The IRBs of all collaborating institutions (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital, Brandeis University, and University of Massachusetts, Boston) all entered into formal cede agreements with Hebrew Senior Life. The study is also overseen by a Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) convened by the National Institute of Aging at the National Institutes of Health. Treatment-specific safety data are reported to the DSMB semi-annually. The DSMB can recommend changes to the protocol or termination of the study.

2.3. Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria

Participant inclusion criteria are purposefully broad given our pragmatic goals, and include individuals who are: 1) living in subsidized senior housing facilities; 2) age > 60; 3) able to understand instructions in English; 4) able to participate safely in Tai Chi exercises at least twice a week; and 5) expected to remain in their current housing facility for 1 year.

Exclusion criteria

Subjects will be excluded if they: 1) are already participating in Tai Chi exercises; 2) have any unstable or terminal illness (e.g., unstable cardiovascular disease, active cancer, unstable COPD, advanced dementia, psychosis); 3)are unable to maintain posture sitting or standing; 4) are unable to speak or understand English; and 5) are unable to hear, see, or understand Tai Chi instructions and assessment questions. We briefly screen volunteers for their cognitive capacity and accept those who can recall at least 2 of 3 words in 3 minutes and 2 of 3 highlighted elements of the study protocol.

2.4. Identification of Housing Facilities and Recruitment of Participants

Our target enrollment is a minimum of 20 participants in each of 16 housing facilities (320 subjects in total) drawn from multiple communities within the Greater Boston area.

Facility eligibility

Eligible facilities include state- and federally-subsidized elderly/disabled housing developments that fall under Federal rules and regulations, monitored by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (Section 8 housing).

Logistics of facility recruitment and participant enrollment

Potential facilities are identified by discussion with community leaders and senior administrative staff of Boston area housing authorities. Senior study personal then contact specific facility administrators and request an onsite in-person introductory meeting to describe the goals of the study, the requirements and responsibilities of participating facilities, and to request preliminary data on facility demographics and markers of health status (e.g., annual ambulance visits) to help match randomization pairs.

Within-facility enrollment is carried out in collaboration with the Center for Survey Research (CSR) of the University of Massachusetts-Boston, a program with demonstrated expertise in recruiting large cohorts of older adults.[42] The CSR is largely composed of experienced interviewers who in several instances are themselves elderly and can relate to and establish trust from elderly populations. Once facility managers have agreed to participate in the study and provide us with access to their residents, CSR and other study staff arrange a series of on-site events designed to attract potential eligible residents, to inform them about the study, and to encourage participation. An initial informational ‘meet and greet’ session is held on a day and time determined for optimal attendance with input from the housing site managers. The lead investigators and members of the study team attend and introduce the details of the study, answer questions, and socialize with the residents. The housing site managers are invited to attend if possible. Weekly recruitment events follow the initial event, and include breakfast events, pizza parties, and ice cream socials.

Interested and willing participants undergo an initial short 2–3 minute eligibility screen conducted on site during the event. Others are asked to provide information needed to contact them and arrange an initial phone screen. If the volunteer passes the initial short screen, they are then contacted by telephone for a more in depth telephone screening, and then they are scheduled for a comprehensive baseline assessment, conducted in a private area within their facility.

Participants are being recruited in two waves. Recruitment occurs during the first six months of each wave. All participants comprising a matched pair of facilities are assessed, on average, within a 2 week period, requiring approximately 8 weeks to assess the volunteers within the 8 facilities of each wave. To assess selection bias within housing facilities, we will be collect sociodemographic information for each of the 16 buildings and compare our study sample to the overall facility sample.

Written informed consent is obtained at the first study visit. A research assistant reviews the details of the study and reviews the entire informed consent document with the participant, either by asking the participant to follow along as the document is read or by having the document read to them. After each section of the consent form, the participant is asked if he/she has any questions. Once the staff is confident that the participant understands all aspects, the participant is asked to sign the form and is given a copy to keep. The participant is given the contact information of the study team members and is encouraged to call at any time for any additional questions that may occur during the participant’s participation in the trial.

2.5. Randomization, Blinding and Concealment

Housing facilities are randomized 1:1 to Tai Chi or educational classes and social calls, stratified by community and matched for size and history of health care utilization when known (e.g., number of EMT transfers over the previous 12 months) as an indicator of frailty of residents at that site. Randomization of a facility does not take place until within-facility recruitment, screening and baseline testing of all participants is completed. Randomization is computer generated and transmitted to the project manager by our unblinded statistician, who maintains this information in a randomization log.

Once randomization is determined, participants within a facility are not blinded, but effort is made to blind the assessors by concealing their site’s treatment assignment and scheduling assessments on days that the intervention is not taking place. All assessments are objective measurements of function or balance or participant responses to general questions that do not refer to their intervention group assignment. Both blinded and unblinded statisticians support the study. The blinded statistician advises the study team, prepares the statistical analysis plan, and performs initial analyses of blinded data. The unblinded statistician performs site randomizations, prepares DSMB reports, and performs interim analyses of unblinded data.

2.7. Study Interventions

Tai Chi

The Tai Chi intervention is adapted from protocols used in our prior trials [9, 21, 41, 43–45] with modifications to: 1) assure safety and emphasize training components specifically relevant to individuals who are frail or transitioning to frailty and 2) adapt to the longer-term nature of our proposed intervention (52 vs. 12 weeks). The protocol emphasizes traditional Tai Chi movements that are easily comprehensible and can be performed repetitively in a flowing manner. In addition, the intervention includes a complementary set of traditional Tai Chi warm-up and cool-down exercises. Both core Tai Chi movements and ancillary warm-up and cool-down exercises emphasize the essential Tai Chi training components including: gentle dynamic stretching and strengthening, slow integrated movements, efficient posture, heightened body awareness and inner focus, active relaxation of body and mind, mindful breathing, and healing imagery and intention.[46] Nine Tai Chi movements following the traditional Cheng Man-Ch’ing’s Yang-style short form[46] are taught over the course of the intervention––‘raising the power’, ‘withdraw and push’, ‘grasp the sparrow’s tail’, ‘brush knee twist step’, ‘cloud hands’, ‘ward-off right and left’, ‘step back to repulse the monkey’, ‘diagonal flying’, and ‘crossing hands’. These 9 movements are progressively added to the warm-up and cool down exercises over the first 24 weeks of the intervention. Chairs are provided for exercises that are performed in a seated position and for resting, as well as for stability as needed when performing standing exercises. Two formal group classes are delivered in each facility at set times each week by experienced Tai Chi instructors in a designated community room within each housing facility for 52 weeks. The content and progression of Tai Chi classes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outline of the MiWish Tai Chi Intervention

| Week | Activities | Approx. Duration (min.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1–2* | Check-in | 2 |

| Tai Chi Warm-up Exercises--Standing | 38 | |

| Tai Chi Pouring | ||

| Tai Chi Swinging and | ||

| Drumming the Body | ||

| Standing meditation | ||

| Hip Circles | ||

| Tai Chi Warm-up | ||

| Exercises—Seated | ||

| Washing with Qi from the Heaven | ||

| Mindful stretching | ||

| Lower Extremities | ||

| Upper Extremities | ||

| Spinal Cord Breathing | ||

| Head and Neck | ||

| Rotations | ||

| Mindful relaxation breathing | ||

| Introduction to Tai Chi | 15 | |

| Movement #1: | ||

| Raising the Power | ||

| Tai Chi Cool-Down | 5 | |

| Exercises | ||

| Self-massage and meridian tapping | ||

| Washing with Qi from heavens | ||

| 3–8 | Check-in | 2 |

| Tai Chi Warm-up exercises | 28 | |

| Review and practice Tai Chi | 5 | |

| Movement #1 | ||

| Learn and practice Tai Chi | 20 | |

| Movements #2 and #3 | ||

| Push and Withdraw | ||

| Grasp the Sparrows Tail | ||

| Tai Chi Cool-Down | 5 | |

| Exercises | ||

| 9–12 | Check-in | 2 |

| Tai Chi Warm-up Exercises | 18 | |

| Review and practice Tai Chi | 15 | |

| Movements #1–3 | ||

| Learn and practice Tai Chi | 20 | |

| Movements #4 and #5 | ||

| Brush Knee Twist Step | ||

| Cloud Hands | ||

| Tai Chi Cool-Down | 5 | |

| Exercises | ||

| 13–18 | Check-in | 2 |

| Tai Chi Warm-up Exercises | 13 | |

| Review and practice Tai Chi | 20 | |

| Movements #1–5 | ||

| Learn and practice Tai Chi | 20 | |

| Movements #6–7 | ||

| Ward Off Right and Left | ||

| Cross Hands | ||

| Tai Chi Cool-Down | 5 | |

| Exercises | ||

| 19–24 | Check-in | 2 |

| Tai Chi Warm-up Exercises | 13 | |

| Review and practice Tai Chi | 25 | |

| Movements #1–7 | ||

| Learn and practice Tai Chi | 15 | |

| Movements #8–9 | ||

| Diagonal Flying | ||

| Step Back to Repulse | ||

| Monkeys | ||

| Tai Chi Cool-Down | 5 | |

| Exercises | ||

| 25–52 | Check-in | 2 |

| Tai Chi Warm-up Exercises | 13 | |

| Refine and practice various combinations of all | ||

| Tai Chi Movements | 40 | |

| Tai Chi Cool-Down | 5 | |

| Exercises |

Nine experienced Tai Chi instructors administer the intervention under the direction of an additional senior instructor. Two instructors are assigned to a given housing facility, teaching there 1 day per week each. All recruited instructors have a minimum of 4 years of training experience (average = 17 y; median =19 y, range = 4–40), have completed a formal 2-year training program led by the senior instructor, and have practical experience teaching older adults with chronic disease. The senior instructor provided a 3-hour training session specific to the study protocol prior to the start of the trial. He also systematically observes classes and assesses fidelity of treatment delivery; provides ongoing feedback to instructors based on observations; and repeats group training sessions at 6-month intervals during each recruitment wave. Participants are given practice DVDs (and DVD players if necessary) and a printed instruction manual well populated with detailed images and descriptions of all exercises. They are instructed to practice at home a minimum of 20 minutes on 3 non-class days each week. Both class attendance and interim home practice are recorded prior to the start of every class.

Education Control

In order to control for the social interaction in the group-based Tai Chi intervention, we utilize an education control intervention in which subjects attend monthly health and wellness group sessions within a common area of each housing facility. Sessions are led by research personnel and include material from Patient Handouts produced by the American Geriatric Society Health in Aging Foundation (www.healthinagingfoundation.org). Sessions are semi-structured, with participants and the session leader seated around a table, and contain approximately 30 minutes of informal lecture interspersed with 30 minutes of group discussion. Additionally, we call the control participants monthly to replicate some of the staff-participant social engagement that occurs during Tai Chi sessions and inquire about falls and health care encounters during the preceding month. Table 2 outlines key features of the educational curriculum.

Table 2.

Outline of the MiWish Health Education control intervention.

| Month | Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | Top 10 Tips for Healthy Aging |

| 2 | Keeping Memory Sharp |

| 3 | Depression and Aging |

| 4 | Balance and Aging |

| 5 | Preventing Falls |

| 6 | Heart Health Managing Stress |

| 7 | Osteoporosis and Bone Health and Aging |

| 8 | Hospital Safety – Preparing for a Hospital Stay |

| 9 | Understanding Delerium and Aging |

| 10 | Healthy Eating on a Budget |

| 11 | Skin Health and Aging |

| 12 | Keeping Active for Good Health in Aging |

2.7. Outcomes

Overview of outcomes

Physical function assessed with the SPPB and health care utilization (including counts of emergency visits, hospitalizations, and skilled nursing and nursing home admissions) assessed at 12 months are co-primary outcomes. Secondary outcomes include multiple aspects of physical function (i.e., mobility, gait, standing balance, grip strength, self-reported physical activity, functional capacity), cognition (i.e., executive function, memory), person-centered measures (i.e., balance confidence, health-related quality-of-life, depression, exercise self-efficacy, satisfaction with the interventions, and expectancy for improvement), and falls. We will collect additional variables known to influence our primary and secondary outcomes, including Tai Chi adherence (i.e., number of sessions attended, hours of home practice), housing facility, age, sex, race, primary language, income, education, Charlson Comorbidity Index, BMI, and history of falls.

Participant flow through testing

Following informed consent, participants undergo a baseline testing protocol that includes evaluation of all primary and secondary outcomes, as well as confounders. Total testing time ranges from 2.5–3.0 hours. Evaluation sessions are sometimes split into two sessions scheduled within a week to minimize fatigue. Assessments are conducted in participants’ apartments or in a private space within the participant’s housing facility. All outcomes measures, except the Mini Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE), are repeated at 6-month and 12-month follow-up assessments. The MMSE is completed at baseline and twelve months.

Baseline and follow-up assessments are overseen by two research teams with two research assistants per team. To avoid residual confounding with treatment, research teams are assigned to matched pairs of sites assigned to the Tai Chi and Health Education treatment groups. Outcomes assessors all participated in extensive pre-study training in standardized operations procedures to maximize inter-rater reliability (see below).

Physical Function

The primary outcome of physical function is assessed with the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).[47] The SPPB includes measures of standing balance (timing of tandem, semi-tandem, and side-by-side stands, test-re-test (T-R-T) correlation=0.97), 4-meter walking speed (T-R-T correlation = 0.89), and ability and time to rise from a chair 5 times (T-R-T correlation = 0.73).[48] The validity of this scale has been demonstrated by showing a gradient of risk for admission to a nursing home and mortality along the full range of the scale from 0–12.[47] In the EPESE population of community-dwelling elders over age 71, the SPPB captured a wide range of functional abilities, and summary scores less than 9 independently predicted disabilities in ADL and mobility at 1–6 years of follow-up.[48, 49] Mobility is assessed by the time taken to complete the Timed Up-and-Go (TUG), [50] which has high T-R-T and discriminant validity in older adults.[51, 52] The kinematics of gait and standing postural control is assessed using wireless movement sensors (Mobility Lab™ APDM Wearable Technologies; Portland Oregon) attached to the participant’s lower extremities and trunk. Gait is assessed during two walking trials at preferred speed in a hallway at the housing site. Participants are able to rest if needed during the test, and a chair is available to sit down if he/she becomes tired. Derived kinematic parameters of gait include average speed and stride time variability.[53] Postural control is assessed during two, 60-second trials of standing in each of the following conditions: quiet standing with eyes open, quiet standing with eyes closed, and standing with eyes-open while concurrently completing an unrelated cognitive “dual task.” The dual task consists of verbalized serial subtractions of 5 from 500. Trial order is randomized for each participant using a randomization chart. Derived parameters of postural control include the average magnitude and speed of the body’s postural sway, as well as the change (i.e., cost) to these metrics induced by closing the eyes or completing the dual task. A trained research assistant “spotter” stands or walks behind the participants in all above assessments of physical function to ensure safety. Grip strength of the dominant hand is assessed with a handgrip dynamometer (Jamar® Hydraulic hand dynamometer). This simple and reliable measure correlates with mortality, survival, disability, and overall function in middle-aged and older adults.[54] Self-reported physical activity is assessed with the validated and reliable Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE).[55] PASE is significantly correlated with health status and physiologic measures such as grip strength, static balance, and leg strength.[56] Self-reported functional capacity is assessed with the widely employed Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) Scale.[57]

Cognitive Function

Cognitive function is assessed using a battery of tests evaluating multiple domains of cognition relevant to aging and frailty, and proven sensitive to change in prior Tai Chi studies.[38, 39] Executive function is assessed with the Trail Making Test. Participants are timed while sequentially connecting a series of numbered circles (part A), as well as connecting an alternating series of numbers and letters (e.g., A-1-B-2-C-3…) (part B). The adjusted trail making score (i.e., part B minus A, sec) is sensitive to changes in executive function and frontal lobe pathology in older adults.[58, 59] Short-term memory is assessed with the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT-R), which is well-tolerated and validated within numerous older adult populations.[60] The HVLT-R consists of three learning trials including 1) immediate recall of 12 nouns (consisting of four words drawn from three semantic categories), 2) a 25 minute delayed recall trial, and 3) a yes/no recognition trial. Dependent variables include total and delayed recall, retention, and the Recognition Discrimination Index.

Person-Centered Measures

Balance confidence is assessed with the Activities Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) questionnaire.[61] The ABC score is reliable, sensitive to different levels of functional mobility in elderly adults, [62] discriminates between older adult fallers and non-fallers with 89% sensitivity and 96% specificity, [63] and is sensitive to change with exercise interventions.[62] Health-related quality-of-life is assessed with the SF-12, a shortened version of the SF-36 health survey[64] that is widely-utilized to assess physical and mental health, as well as the outcomes of healthcare services. This questionnaire is valid and reliable (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.72–0.89) within numerous elderly populations, including community-dwelling older adults[65, 66], minorities[67] and those with physical[68] and mental[69] disabilities. Depressive symptoms are assessed with the Center of Epidemiology Studies-Depression Scale Revised (CESD-R).[70] This validated measure has been used extensively in epidemiology studies and consists of 20 questions regarding feelings of depression, worthlessness, loneliness, energy level, and fear. The CESD-R has high internal consistency (r=0.90) and a test-retest reliability of 0.51.[71] Exercise self-efficacy is assessed with a valid and reliable 26-item exercise self-efficacy questionnaire, [72] which quantifies one’s general beliefs towards exercise, the likelihood of participating in regular exercise, and overcoming barriers. Satisfaction with programs and expectancy for improvement is assessed using instruments employed in prior Tai Chi trials.[73]

Falls

Falls are defined as any event in which the participant unintentionally comes to rest on the ground or other lower level, not as a result of a major intrinsic event or an overwhelmingly external hazard.[74] Study personnel conduct monthly interviews in-person or by phone, to discuss the incidence and characteristics of falls. All participants in both study groups, are asked at each class about adverse events, including falls. When a fall or other event is reported, the participant is contacted within 24 hours to obtain details of the event.

Medical Utilization Outcomes

We are tracking self-reports of falls, emergency visits and hospitalizations, including reported post-hospital rehabilitation stays or nursing home admissions during the monthly telephone calls.

2.8. Safety Monitoring

We utilize a multi-pronged approach to monitor safety and track adverse events throughout the study with formal oversight from institutional IRBs and a Data Safety and Monitoring Board. Participants are followed regularly during their enrollment for the development of adverse events. Adverse events are carefully tracked in several ways.

Class Sign in Log

At each class during the intervention period, research personnel log in each participant electronically, utilizing a REDCap™ EDC (REDCap Software, version 6.12.1, Vanderbilt University) login developed for the study. At the time of log-in each participant is asked if they have experienced any adverse events, falls or hospitalizations. If a participant reports that “yes” they have experienced an adverse event, the database immediately sends an email alert to the study Project Director for expedited follow up of the details of the reported event. For participants in the Tai Chi intervention classes, participants are also asked about Tai Chi practice outside of the class, i.e, number of times practiced length of time practiced, as well as any adverse events that took place during practice.

Visit Follow up Surveys

After each of the three study assessments (baseline, six month follow-up and 12 month follow-up), participants are contacted within one week to complete the visit follow up survey and inquire about adverse events.

Monthly Phone Call Records

Participants receive a social telephone contact each month to establish and foster a positive study experience, but also to assess for any falls or other adverse events, and to track health care interactions such as hospitalizations and ER visits.

When an adverse event is reported through any of the above tracking mechanisms, the Project Director is notified. Any adverse events experienced are followed up by the Project Director and reported to the HSL IRB according to the established guidelines.

Data Safety Monitoring Board

A Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) has been established to act in an advisory capacity to the National Institute of Aging (NIA) Director to monitor participant safety, data quality and progress of the study. This DSMB consists of 3 members approved by the Program Director of NIA, and includes experts in the fields of aging and exercise interventions, clinical trial methodology, and biostatistics. The DSMB Chair also serves as the study safety officer. Any serious adverse events that might be related to the intervention are reported to the Chair of the DSMB, the IRB, and the NIA Program Official within a week of their occurrence. Meetings of the DSMB are held approximately two times a year or at the request of the Chairperson.

2.9. Statistical analysis plan

Sample Size Calculation and Justification

Aim 1

Power for the primary analysis of SPPB was estimated by extrapolating results from our preliminary study in similar housing facilities where the mean baseline SPPB score was 8 out of a total possible score of 12 (see figure 2). In a mixed model ANCOVA of 3-month change in SPPB that included a site-level random effect of treatment, the standard error for the fixed effect of treatment was 0.268. Extrapolating from 3 months to 12 and from 2 sites to 16 (each study with 20 participants per site), the estimated standard error for a treatment effect on 12-month change in SPPB would be 0.268 × 12/3 × sqrt(2/16) = 0.379. Given that estimate, the current study would have 85% power to detect a 1.38 point difference in 12-month change in SPPB based on a two-tailed test at alpha = 0.023. Even with up to 20% loss to follow-up, the study would be well powered to detect treatment-dependent differences in 12-month change in SPPB of less than 2 points – a clinically meaningful difference.

Aim 2

Power for effects of Tai Chi on health care utilization was estimated from data collected in the COLLAGE Project at Hebrew SeniorLife and Kendall Corporation. Based on 90-day retrospective self reports from 668 residents of 22 housing and low-income housing sites, the mean rate of physician visits, overnight hospitalizations, and ED visits was 2.2 total encounters per person with an over-dispersion coefficient of 1.9, combining excess variation due to both person-to-person and site-to-site variation in underlying service needs. Given these estimates, our study will have 80% power to detect a 27% reduction in total encounters over 90-days for a two-tailed test at alpha = 0.05. Extrapolating conservatively to a mean annual total encounter rate of 6 encounters/person-year, the study would have 80% power to detect a reduction of just one encounter per year, assuming no increase in over-dispersion for the full-year counts. Even if over-dispersion increases 50% due to non-independence of successive 90-day intervals, the study would still have 80% power to detect a 20% reduction in mean annual total encounter rate. Previous studies of Tai Chi have reported a 30% reduction in fall rates, as well as improvements in many of the chronic illnesses (COPD, CHF, depression) that precipitate emergency, hospital, and doctor’s visits. Given that the minimum effects of Tai Chi on measures of health care utilization and cost that are detectable with high probability will be larger if we have under-estimated year-to-year or site-to-site variation, one goal of our interim analysis is to update our estimates of these nuisance parameters and re-calculate power.

Statistical Analysis

Specific Aim 1

The effect of the Tai Chi intervention on functional performance as measured by SPPB will be estimated from a shared-baseline linear mixed model with fixed effects for age, follow-up time, age x time interaction, and treatment x time interaction and random effects of site pair, site within site pair, participant within site, site pair x time, site pair x treatment x time, site x time, and participant x time interactions. The shared baseline across treatment groups reflects homogeneity of the population with respect to treatment prior to random assignment and adjusts for effects of baseline level in a manner equivalent to ANCOVA.[75] The random effects acknowledge the expected correlations among sites within a community, among participants within a site, and among repeated longitudinal assessments of each participant. This approach also naturally accommodates unequal enrollment across sites and loss to follow-up, even otherwise informative loss to follow-up, if well predicted by the observed data on participants prior to drop-out. All participants will be included in the primary analysis according to their treatment assignment, following the intention-to-treat principle. Primary inference will be based on a two-tailed test at alpha = 0.023 of the fixed treatment x time interaction estimating Tai Chi-dependent improvement in rates of change in SPPB. Effects on 12-month change in SPPB are tested at two-tailed alpha = 0.023 to accommodate two co-primary endpoints and one interim look that will spend 0.001 one-tailed. An additional alpha = 0.002 is reserved for one interim analysis. The total two-tailed alpha = 0.025 for testing SPPB preserves an overall type I error rate of 0.05 for the functional and utilization co-primary aims.

Secondary continuous outcomes will be analyzed using the same model. Counts of falls will be analyzed in a similar mixed effect negative binomial regression. Both nominal p-values and step-down Bonferroni-adjusted p-values will be calculated for analyses of secondary outcomes. Secondary analyses will consider effects of treatment dose based on attendance records. Given the possible influence of perceived treatment efficacy on adherence, which could bias the effect of adherence on Tai Chi efficacy, these analyses will be exploratory. Other secondary analyses will determine if Tai Chi is more effective or uniquely effective for specific subgroups of participants by including fixed effects for subgroup indicators and their interactions with time and treatment x time.

Specific Aim 2

To determine the effects of the Tai Chi intervention on health care utilization in poor, multiethnic, elderly residents of subsidized housing facilities. The primary outcome is health care utilization, which includes number of emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and skilled nursing and nursing home admissions. The effect of the Tai Chi intervention this outcome will be estimated in generalized linear mixed models. For primary analysis, count data (e.g., number of ED visits, hospitalizations, etc.) will be modeled as over-dispersed Poisson or negative binomial distributed outcomes. All models will include fixed effects of treatment group, time period and treatment x period interaction and random effects of site pair, site within site pair, and site pair x treatment interaction and their interactions with period to accommodate covariance among residents within a given facility or community. Models will include additional fixed effects of age, sex, race, primary language, income, education, BMI, and history of falls to adjust for known predictors of health care utilization and cost. Inference will be based on a two-tailed test at alpha = 0.023, reserving alpha = 0.002 for one interim analysis, as in the analysis for Aim 1. Persistence of such an effect will be tested in a similar linear contrast between the intervention and post-intervention periods. Secondary analyses will test the effects of adherence and differential effects among subgroups using similar approaches to those for Aim 1.

Interim analysis

One interim analysis for efficacy, futility, and sample size re-estimation is planned after all participants enrolled in wave 1 have completed their 12-month assessment (or dropped out). The study will be stopped for efficacy based on a two-sided Haybittle-Peto boundary at alpha = 0.002 for each co-primary outcome. A non-binding proposal to stop the study for futility will be based on a beta spending rule linear in information time, or beta = 0.10. The study will be stopped early for efficacy or futility only if both co-primary outcomes have demonstrated efficacy or futility. Observed dropout and community-level, site-level, and participant-level variance components and their collective effect on the standard error of the treatment x time interaction term will be estimated. The benefit of increasing the number of sites or the number of participants per site will be considered based on the pre-specified minimum treatment effects of interest on SPPB and total health care utilization. Results of the efficacy and futility analysis will be shared only between an unblinded statistician and the DSMB. Estimates of the nuisance parameters and their effect on power for the pre-specified effect sizes will be shared with the study team given negligible risk of deducing the treatment effect and the importance of logistical constraints in planning any increase in sample size.

2.10. Data Management

Study data are collected and managed using the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tools hosted at Hebrew SeniorLife Institute for Aging Research. REDCap provides a secure, web-based interface for validated data entry with auditing features for tracking data manipulation and export, as well as export of data to common statistical packages and data importation from external data sources.

Discussion

The MiWish study represents one of the first large scale cluster randomized trials to date evaluating the effectiveness and components of cost effectiveness of Tai Chi––a promising mind-body exercise intervention for multiple frailty- and age-related morbidities. Novel aspects of this study include: The focus on evaluating an understudied and underserved population that is a significant driver of societal and medical costs; evaluating both effectiveness and cost-effectiveness within the same study; pragmatically delivering interventions in housing facilities; and delivering Tai Chi interventions and monitoring outcomes for a full year. A broader implementation-related goal of this study is to prepare the necessary training and protocol manuals for widespread translation and dissemination of the Tai Chi program to housing facilities in other communities across the U.S., if effectiveness and ability to offset medical care utilization and spending is demonstrated.

Clinical trials evaluating multi-component interventions like Tai Chi pose unique design challenges. It has been argued that placebo-controlled explanatory trial designs widely used to evaluate pharmacological interventions are not appropriate due to challenges associated with distinguishing specific vs. non-specific effects, controlling for multiple specific effects, characterizing dosage, and participant blinding, among other reasons.[76, 77] Employing elements of pragmatic designs has been suggested as a way to overcome these challenges.[76, 78–80] Using the framework of the revised Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary (PRECIS-2), [81] the MiWish Study is best described as a predominantly pragmatic trial with elements of explanatory trials that enhance the degree of internal validity. Elements that are pragmatic include: our relatively broad participant eligibility criteria; recruitment of individuals from multiple housing facilities within and between diverse Greater Boston area communities; integrating interventions into the community spaces and weekly activities within a facility; conducting all baseline and follow-up testing in participants apartments or private spaces within their facility; the inclusion of outcomes that are patient centered (e.g. falls, quality of life) and of practical interest to policy makers (e.g. cost effectiveness); and the use of an intent-to-treat paradigm for primary analyses. Elements of our study design that are more explanatory include: inclusion of an active control group to partially account for attention and increase study equipoise; significant efforts to encourage class attendance and overall protocol compliance; relatively intensive and frequent follow-up assessments (every 6 months for all outcomes; more frequently for fall and AE’s); inclusion of physiological (e.g. COP, gait variability) or composite functional outcomes (e.g. SPPB) not directly relevant to patients; and inclusion of planned per-protocol secondary analyses. Additionally, while the Tai Chi protocol was specifically designed to reflect generic Tai Chi movements and principles widely used across many styles of Tai Chi, [46] (i.e., relatively pragmatic), it was delivered by carefully selected and trained experienced instructors who received regular training and fidelity monitoring in the delivery of this protocol (i.e., relatively explanatory). In summary, the MiWish trial has attempted to strike a balance between pragmatic and explanatory elements into a novel cluster RCT. Pragmatic elements enhance broader generalizability and translatability to community-based programs and inform policy. Explanatory elements minimize bias, help interpret results, and leverage financial investments in the overall trial to also explore relevant physiological and functional outcomes that may contribute to the design of future studies.

The ongoing conduct of MiWish has posed some logistical challenges. One issue perhaps common to all cluster RCTs, but perhaps especially challenging in frail and underserved communities, is site recruitment. Contributing to this challenge is the need to identify and recruit pairs of geographically proximal houses that share common sociodemographic and broad health characteristics (latter assessed using records of ambulance visits), and that are also large enough to provide the minimum number of eligible participants per site needed to form adequate-sized intervention groups. Overcoming this challenge has required establishing strong partnerships with senior housing authority leaders and individual housing facility site managers. Joint meetings between senior study staff and housing community leaders have been essential. The meetings provide a forum for study leaders to clearly describe study aims, clarify logistical concerns, and to emphasize that our goals are collaborative–– we provide a no-cost year long program to each of the housing communities (Tai Chi or health education) in exchange for each site allowing formal data collection. An important factor helping buy-in and site recruitment is that when the data collected at each site are aggregated and analyzed, they will provide important evidence that will inform policy, which is turn may catalyze future support for health promoting programs at their facility as well as nationally.

Recruitment and retention of individual participants within sites has also been a challenge. Initial recruitment strategies were developed with input from a social behavior expert (ML) and an assembled study staff with expertise in recruiting among the elderly. Some initial initiatives employed to attract and recruit participants within a community include hosting multiple in-house informational and social events (ice cream, pizza, breakfasts) scheduled at different times of the day, holding raffles for all attendees, and giving away small gifts (e.g., pens, coffee cups) with study logos and contact information printed on them. The effectiveness of these initiatives have varied from site to site, and we have learned that we need to take a pluralistic and adaptive approach, emphasizing different initiatives in different communities.

Once enrolled, maintaining compliance in some communities has also been challenging. Of note, the year-long Tai Chi program delivered in this study represents the longest program evaluated in a trial in the U.S. In addition to providing home practice DVDs and printed study manuals, to enhance attendance/adherence, we assigned a dedicated study staff to attend each class, and to call all participants prior to every class, and to monitor attendance. The established relationship between the staff member and participants, in addition to participants’ relationships to instructors and class mates, has been instrumental in enhancing adherence. Additional incentives to promote adherence in both the Tai Chi and education group include having participants’ sign contracts outlining their responsibilities and providing small prizes for good attendance. Our use of experienced Tai Chi instructors that are skilled at building rapport with participants has also been instrumental. Despite these efforts, adherence has been variable, and relatively poor at some sites. To better understand adherence, during Phase I of recruitment plan (i.e. first 8 facilities) we also added a qualitative sub-study funded by a Roybal Center pilot grant that employs focus groups to better learn about facilitators and barriers to participation, both for sites with good attendance and well as for those with poorer attendance. Importantly, effort is made to interview participants who have a history of only intermittent attendance and those who have fully withdrawn. Lessons learned from these focus groups and individual interviews will be applied to enhance adherence during Phase II of our study.

A limitation of the study is the use of patient recall to document falls and health care utilization. Studies indicate that the accuracy of recall of health care utilization encounters can vary.[82] However, recall time frame is an important factor in accuracy, and our study relies on monthly reports, a relatively short time frame. As well, subjects in the MiWish study are required to have adequate cognitive ability to participate, which is another factor important in increasing the accuracy of recall.

In summary, the MIWish study addressed the large and growing problem of supporting the health and health care needs of frail seniors living in subsidized housing. If Tai Chi is found to be effective in combating frailty, improving residents’ functional abilities, and reducing their health care costs, justification and materials will be in place to translate and disseminate training programs at a national level.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by multiple grants from the National Institutes of Health [R01AG025037-09, K24AT009282, P30AG048785].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dall TM, et al. An aging population and growing disease burden will require a large and specialized health care workforce by 2025. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(11):2013–20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease, C. and Prevention. Public health and aging: projected prevalence of self-reported arthritis or chronic joint symptoms among persons aged >65 years--United States, 2005–2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(21):489–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salkin P. A Quiet Crisis in America: Meeting the Affordable Housing Needs of the Invisible Low-Income Healthy Seniors. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law Policy. 2009:15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Dual Eligible Beneficiaries and Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations. Washington DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsons PL, MB, Ratliff S, Lapane KL. Subsidized housing not subsidized health: health status and fatigue among elders in public housing and other community settings. Ethn Dis. 2011 Winter;21(1):85–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrow DE, et al. An evaluation of the effects of Tai Chi Chuan and Chi Kung training in patients with symptomatic heart failure: a randomised controlled pilot study. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(985):717–21. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2007.061267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caminiti G, et al. Tai chi enhances the effects of endurance training in the rehabilitation of elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Rehabil Res Pract. 2011;2011:761958. doi: 10.1155/2011/761958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan L, Yan J, Guo Y. Effects of Tai Chi training on exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012 doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh GY, et al. Tai chi exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(8):750–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin CL, Lin CP, Lien SY. The effect of tai chi for blood pressure, blood sugar, blood lipid control for patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Hu Li Za Zhi. 2013;60(1):69–77. doi: 10.6224/JN.60.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeh GY, et al. The Effect of Tai Chi Exercise on Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review. Preventive Cardiology. 2008;11:82–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7141.2008.07565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young DR, et al. The effects of aerobic exercise and T’ai Chi on blood pressure in older people: results of a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;4(3):277–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lan C, Chen SY, Lai JS. Changes of aerobic capacity, fat ratio and flexibility in older TCC practitioners: a five-year follow-up. Am J Chin Med. 2008;3(6):1041–50. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X08006442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsang TW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of Kung Fu training for metabolic health in overweight/obese adolescents: the “martial fitness” study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2009;22(7):595–607. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2009.22.7.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang R, et al. Effects of Tai Chi rehabilitation on heart rate responses in patients with coronary artery disease. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2010;38(3):461–472. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X10007981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang RY, et al. The effect of t’ai chi exercise on autonomic nervous function of patients with coronary artery disease. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(9):1107–13. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Channer KS, et al. Changes in haemodynamic parameters following Tai Chi Chuan and aerobic exercise in patients recovering from acute myocardial infarction. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72(848):349–51. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.72.848.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng SM, et al. Tai chi exercise for patients with heart disease: a systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Altern Ther Health Med. 2012;18(3):16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan AW, et al. Tai chi Qigong improves lung functions and activity tolerance in COPD clients: A single blind, randomized controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2011;19(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung RW, McKeough ZJ, Alison JA. Tai Chi as a form of exercise training in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2013;7(6):587–92. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2013.839244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeh GY, et al. Tai Chi Exercise for Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Pilot Study. Respiratory Care. 2010;55(11):1475–1482. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Audette JF, et al. Tai Chi versus brisk walking in elderly women. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):388–93. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hui SSC, Woo J, Kwok T. Evaluation of energy expenditure and cardiovascular health effects from Tai Chi and walking exercise. Hong Kong Medical Journal = Xianggang Yi Xue Za Zhi/Hong Kong Academy Of Medicine. 2009;15(Suppl 2):4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor-Piliae RE, Froelicher ES. Effectiveness of Tai Chi exercise in improving aerobic capacity: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19(1):48–57. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf SL, et al. The effect of Tai Chi Quan and computerized balance training on postural stability in older subjects. Atlanta FICSIT Group. Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies on Intervention Techniques. Phys Ther. 1997;77(4):371–81. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.4.371. discussion 382-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logghe IH, et al. The effects of Tai Chi on fall prevention, fear of falling and balance in older people: A meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine. 2010;51(3/4):222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wayne PM, et al. Tai Chi Training may Reduce Dual Task Gait Variability, a Potential Mediator of Fall Risk, in Healthy Older Adults: Cross-Sectional and Randomized Trial Studies. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:332. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu G. Evaluation of the effectiveness of Tai Chi for improving balance and preventing falls in the older population--a review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:746–754. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobson BH, et al. The effect of T’ai Chi Chuan training on balance, kinesthetic sense, and strength. Percept Mot Skills. 1997;84(1):27–33. doi: 10.2466/pms.1997.84.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lan C, et al. Tai Chi Chuan to improve muscular strength and endurance in elderly individuals: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(5):604–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(00)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu G, et al. Improvement of isokinetic knee extensor strength and reduction of postural sway in the elderly from long-term Tai Chi exercise. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(10):1364–9. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.34596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li F, et al. A randomized controlled trial of patient-reported outcomes with tai chi exercise in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29(4):539–45. doi: 10.1002/mds.25787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carbonell-Baeza A, et al. Preliminary Findings of a 4-Month Tai Chi Intervention on Tenderness, Functional Capacity, Symptomatology, and Quality of Life in Men With Fibromyalgia. Am J Mens Health. 2011 doi: 10.1177/1557988311400063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C. Tai Chi improves pain and functional status in adults with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a pilot single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Med Sport Sci. 2008;52:218–29. doi: 10.1159/000134302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang C. Role of Tai Chi in the Treatment of Rheumatologic Diseases. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11926-012-0294-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang C, et al. A novel comparative effectiveness study of Tai Chi versus aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0548-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang C, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Tai Chi Versus Physical Therapy for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):77–86. doi: 10.7326/M15-2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng ST, et al. Mental and Physical Activities Delay Cognitive Decline in Older Persons With Dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wayne PM, et al. Effect of tai chi on cognitive performance in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(1):25–39. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang C, et al. Tai Chi on psychological well-being: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complementary & Alternative Medicine. 2010;10:16p. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manor B, et al. Functional benefits of tai chi training in senior housing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(8):1484–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leveille SG, et al. The MOBILIZE Boston Study: design and methods of a prospective cohort study of novel risk factors for falls in an older population. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGibbon CA, et al. Tai Chi and vestibular rehabilitation improve vestibulopathic gait via different neuromuscular mechanisms: preliminary report. BMC Neurol. 2005;5(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moy ML, et al. Long-term Exercise After Pulmonary Rehabilitation (LEAP): Design and rationale of a randomized controlled trial of Tai Chi. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt B):458–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salmoirago-Blotcher E, et al. Design and methods of the Gentle Cardiac Rehabilitation Study--A behavioral study of tai chi exercise for patients not attending cardiac rehabilitation. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;43:243–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wayne PM, Fuerst ML. The Harvard Medical School Guide To Tai Chi: 12 Weeks to a Healthy Body, Strong Heart & Sharp Mind. United States of America: Shambhala Publications Inc; 2013. p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guralnik JM, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guralnik JM, et al. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guralnik JM, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(4):M221–31. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin MR, et al. Psychometric comparisons of the timed up and go, one-leg stand, functional reach, and Tinetti balance measures in community-dwelling older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1343–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys Ther. 2000;80(9):896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hausdorff JM. Gait variability: methods, modeling and meaning. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2005;2:19. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuh D, et al. Grip strength, postural control, and functional leg power in a representative cohort of British men and women: associations with physical activity, health status, and socioeconomic conditions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(2):224–31. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Washburn RA, et al. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(2):153–62. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Washburn RA, et al. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): evidence for validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(7):643–51. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Avlund K, Schultz-Larsen K, Kreiner S. The measurement of instrumental ADL: content validity and construct validity. Aging (Milano) 1993;5(5):371–83. doi: 10.1007/BF03324192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Libon DJ, GG, Malamut BL, et al. Age, executive functions, and visuospatial functioning in healthy older adults. Neuropsychology. 1994;8(1):38. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pugh KG, et al. Selective impairment of frontal-executive cognitive function in african americans with cardiovascular risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;5(10):1439–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shapiro AM, et al. Construct and concurrent validity of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-revised. Clin Neuropsychol. 1999;13(3):348–58. doi: 10.1076/clin.13.3.348.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Powell LE, Myers AM. The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50A(1):M28–34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.1.m28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Myers AM, et al. Psychological indicators of balance confidence: relationship to actual and perceived abilities. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51(1):M37–43. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.1.m37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lajoie Y, Gallagher SP. Predicting falls within the elderly community: comparison of postural sway, reaction time, the Berg balance scale and the Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale for comparing fallers and non-fallers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2004;38(1):11–26. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(03)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jakobsson U. Using the 12-item Short Form health survey (SF-12) to measure quality of life among older people. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(6):457–64. doi: 10.1007/BF03324731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Resnick B, Nahm ES. Reliability and validity testing of the revised 12-item Short-Form Health Survey in older adults. J Nurs Meas. 2001;9(2):151–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cernin PA, et al. Reliability and validity testing of the short-form health survey in a sample of community-dwelling African American older adults. J Nurs Meas. 2010;18(1):49–59. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.18.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luo X, et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the short form 12-item survey (SF-12) in patients with back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28(15):1739–45. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000083169.58671.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salyers MP, et al. Reliability and validity of the SF-12 health survey among people with severe mental illness. Med Care. 2000;38(11):1141–50. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eaton WSC, Ybarra M, Muntaner C, Tien A. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD-R) In: Maruish M, editor. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment (3rd Ed.),. Volume 3: Instruments for Adults. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Himmelfarb S, Murrell SA. Reliability and validity of five mental health scales in older persons. J Gerontol. 1983;38(3):333–9. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Neupert SD, Lachman ME, Whitbourne SB. Exercise self-efficacy and control beliefs: effects on exercise behavior after an exercise intervention for older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2009;17(1):1–16. doi: 10.1123/japa.17.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wayne PM, et al. Impact of Tai Chi exercise on multiple fracture-related risk factors in post-menopausal osteopenic women: a pilot pragmatic, randomized trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Quach L, et al. The nonlinear relationship between gait speed and falls: the Maintenance of Balance, Independent Living, Intellect, and Zest in the Elderly of Boston Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(6):1069–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liang Ky, Zs Longitudinal data analysis for continuous and discrete responses for pre-post designs. The Indian Journal of Statistics. 2000;62:134–148. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wayne P, Kaptchuk T. Challenges inherent to Tai Chi Research: Part II--Defining the intervention and optimal study design. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(2):191–197. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.7170b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wayne P, Kaptchuk T. Challenges inherent to Tai Chi research: Part I--Tai Chi as a complex multi-component intervention. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;1(1):95–102. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.7170a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wayne PM, et al. Tai Chi for osteopenic women: design and rationale of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:40–40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wayne PM, et al. Complexity-Based Measures Inform Effects of Tai Chi Training on Standing Postural Control: Cross-Sectional and Randomized Trial Studies. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Witt CM, et al. Effectiveness guidance document (EGD) for Chinese medicine trials: a consensus document. Trials. 2014;15:169. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Loudon K, et al. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ. 2015;350:h2147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(2):217–35. doi: 10.1177/1077558705285298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]