Summary

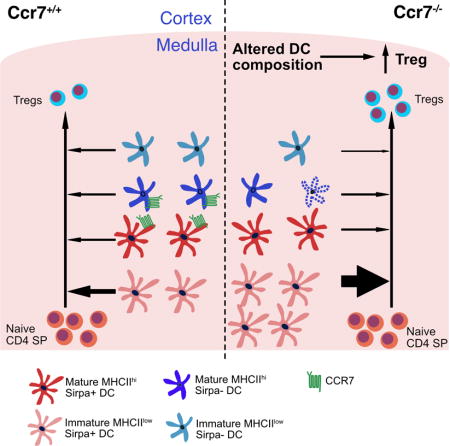

Upon recognition of auto-antigens, thymocytes are negatively selected or diverted to a regulatory T cell (Treg) fate. CCR7 is required for negative selection of auto-reactive thymocytes in the thymic medulla. Here we describe an unanticipated contribution of CCR7 to intrathymic Treg generation. Ccr7−/− mice have increased Treg cellularity, due to a hematopoietic, but non-T cell autonomous CCR7 function. CCR7 expression by thymic dendritic cells (DC) promotes survival of mature Sirpα− DC. Thus, CCR7 deficiency results in apoptosis of Sirpα− DC, which is counterbalanced by expansion of immature Sirpα+ DC, which efficiently induce Treg generation. CCR7 deficiency results in enhanced intrathymic generation of Treg at the neonatal stage and in lymphopenic adults, when Treg differentiation is critical for establishing self-tolerance. Together these results reveal a complex function for CCR7 in thymic tolerance induction, in which CCR7 not only promotes negative selection, but also governs intrathymic Treg generation via non-thymocyte intrinsic mechanisms.

Keywords: CCR7, Regulatory T cells, dendritic cells, chemokine receptor, thymocyte development

eTOC blurb

CCR7 promotes thymocyte medullary entry and is thus required for negative selection. Hu et al. show that CCR7 also regulates intrathymic generation of regulatory T cells (Treg) through a non-T cell intrinsic mechanism. CCR7 regulates the composition of the thymic conventional DC compartment, which in turn restrains intrathymic Treg generation.

Introduction

After positive selection, thymocytes differentiate into CD4+ single positive (CD4SP) or CD8+ single positive (CD8SP) cells and upregulate the chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR7 to guide them from the cortex into the medulla (Cowan et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2015a, 2015b). The thymic medulla is enriched for antigen presenting cells (APC) that display numerous self-antigens to tolerize autoreactive thymocytes. The two major classes of medullary APC are dendritic cells (DC) and medullary thymic epithelium cells (mTEC) (Derbinski and Kyewski, 2010). Upon auto-antigen recognition, thymocytes undergo apoptosis or adopt a regulatory T cell (Treg) fate (Klein et al., 2014). Treg potently suppress autoreactive effector T cell responses (Asano et al., 1996; Sakaguchi et al., 1995); thus, Treg deficiency leads to severe autoimmune pathology in humans and mice (Bennett et al., 2001; Brunkow et al., 2001; Josefowicz et al., 2012). Both mTEC and DC contribute to Treg generation (Perry et al., 2014; Proietto et al., 2008). mTEC express the transcriptional regulator Aire which promotes low level expression of a broad spectrum of self-antigens that induce thymocyte negative selection and Treg generation (Anderson et al., 2002; Aschenbrenner et al., 2007; Liston et al., 2003). The three major subsets of thymic DC, Sirpα+ DC, Sirpα− DC, and plasmacytoid DC (pDC) (Wu and Shortman, 2005), can also induce Treg differentiation (Martin-Gayo et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2014; Proietto et al., 2008). Sirpα+ DC and pDC mature extrathymically and migrate into the thymic medulla, where they present antigens acquired in peripheral tissues or from the blood (Bonasio et al., 2006; Hadeiba et al., 2012; Li et al., 2009). Sirpα− DC, which differentiate intrathymically, can present self-antigens acquired directly from mTEC (Hubert et al., 2011; Perry et al., 2014). Thus, each DC subset can display a unique complement of intrinsic and acquired self-antigens, likely enabling selection of Treg with non-overlapping specificities (Leventhal et al., 2016; Perry et al., 2014). In addition to displaying self-antigens, DC express other molecules essential for Treg generation, including CD80/CD86, CD70 and IL-2 (Coquet et al., 2013; Salomon et al., 2000; Weist et al., 2015).

Thymocytes must enter the medulla and scan mTEC and DC efficiently to encounter the full spectrum of self-antigens that enforce central tolerance. The chemokine receptor CCR7 is critical for medullary accumulation and rapid motility of SP thymocytes (Ehrlich et al., 2009; Ueno et al., 2002). In CCR7 deficient mice, SP thymocytes do not efficiently encounter self-antigens displayed by medullary APC (Nitta et al., 2009), auto-reactive thymocytes are not effectively deleted, and autoimmunity ensues (Davalos-Misslitz et al., 2007a; Kurobe et al., 2006). Because the medulla is important for Treg generation (Coquet et al., 2013; Cowan et al., 2013), we anticipated that impaired medullary entry would inhibit Treg generation; however, we find that Treg cellularity increases in Ccr7−/− thymi.

In this study, we investigated the mechanism by which CCR7 deficiency results in increased thymic Treg cellularity. Bone marrow chimeras revealed that increased Treg cellularity was due to CCR7 deficiency in hematopoietic cells, but not in the T cell lineage. In adult Ccr7−/− mice, increased thymic Treg cellularity could be accounted for by re-entry of peripheral Treg, consistent with a previous report (Cowan et al., 2016). Surprisingly, however, intrathymic generation of Treg was enhanced in Ccr7−/− neonates and in lympho-deficient bone marrow chimera recipients. Treg generated during the neonatal period and following recovery from lymphodepletion are particularly critical for maintaining self-tolerance (Guerau-de-Arellano et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2015). To investigate the mechanism by which CCR7 deficiency results in increased Treg generation, we analyzed mixed bone marrow chimeras and found that CCR7 deficiency in thymic DCs was responsible for increased Treg cellularity. CCR7 deficiency selectively impaired survival of mature Sirpα−MHC-IIhi DCs, resulting in an increased frequency of Sirpα+MHCIIlo DCs, a subset that efficiently promotes Treg generation. Thus, CCR7 deficiency promotes an increase in thymic Treg cellularity both by enhancing peripheral recruitment of Treg in the adult and by skewing the thymic DC compartment to favor Treg generation in the neonate and following lymphodepletion.

Results

Treg cellularity is increased in Ccr7−/− thymi

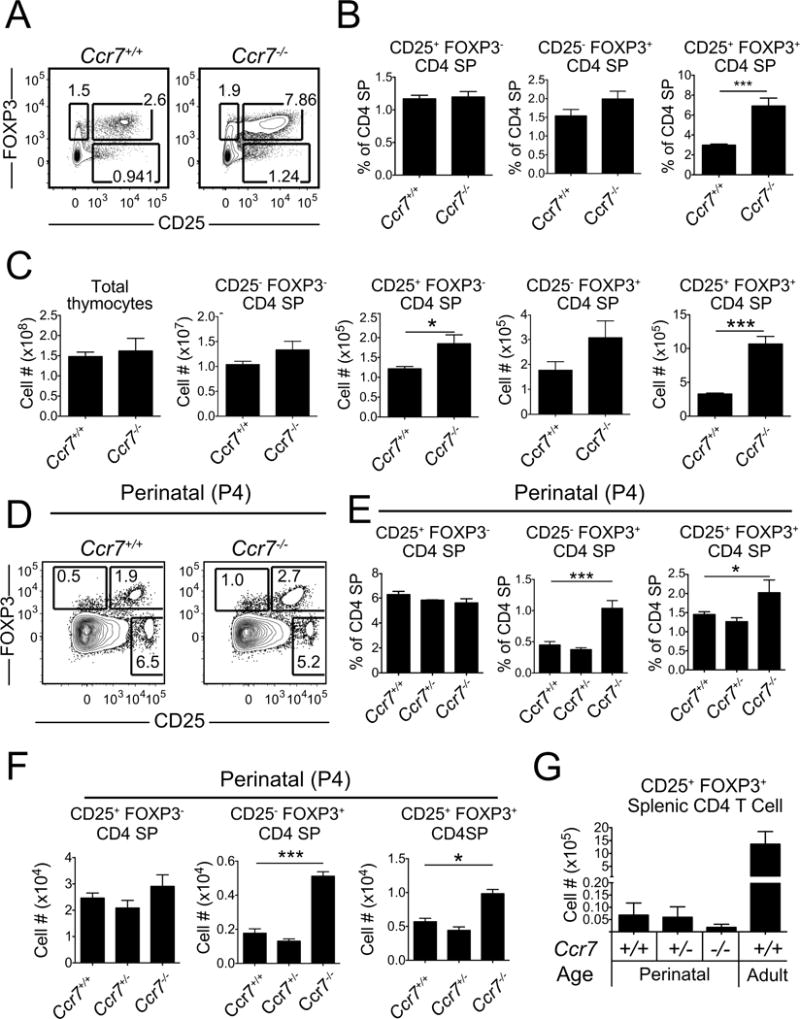

CCR7 is required for efficient medullary accumulation and negative selection of auto-reactive SP thymocytes (Ehrlich et al., 2009; Nitta et al., 2009; Ueno et al., 2004). Given that Treg are also generated in the medulla when thymocytes recognize auto-antigens (Aschenbrenner et al., 2007; Jordan et al., 2001; Moran et al., 2011), we hypothesized that Treg generation would be impaired in Ccr7−/− thymi. Instead, both the percentage and absolute number of FOXP3+ CD25+ Treg cells were increased in Ccr7−/− thymi (Figures 1A–1C), consistent with a recent report (Cowan et al., 2016). Treg arise from both CD25−FOXP3+ and FOXP3−CD25+ Treg progenitors (Tai et al., 2013). The number of FOXP3−CD25+ Treg progenitors was increased in Ccr7−/− mice, with a trend of increased CD25−FOXP3+ progenitors. In agreement with previous reports (Menning et al., 2007; Schneider et al., 2007), CCR7 deficiency did not alter the capacity of Treg to suppress naïve T cell proliferation in vitro (Figure S1A).

Figure 1. CCR7 deficiency results in an increased number and percentage of thymic Treg in adult and neonatal mice.

(A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the percentage of FOXP3− CD25+ and FOXP3+ CD25− Treg progenitors and FOXP3+ CD25+ Treg cells within the CD4SP population of Ccr7+/+ and Ccr7−/− mice at one month of age. (B–C) Quantification of the (B) percent and (C) number of cells of the indicated subsets, as in (A). Data in B and C were compiled from 3 experiments. n = 8 mice per genotype. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of FOXP3− CD25+, FOXP3+ CD25− and FOXP3+ CD25+ cells within the CD4SP population in perinatal P4 Ccr7+/+ and Ccr7−/− mice. (E–F) Quantification of the (E) percent and (F) number of the indicated cell types within the CD4SP population in P4 Ccr7+/+, Ccr7+/− and Ccr7−/− mice. (G) Absolute number of FOXP3+ CD25+ Treg in the spleen of P4 Ccr7+/+, Ccr7+/− and Ccr7−/− mice and of adult Ccr7+/+ mice at 1 month of age. Data in E-G were compiled from 3 experiments. n = 9 mice per genotype. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM. * p<.05, *** p< 0.001. See also Figure S1.

Peripheral Treg recirculate into the thymus and account for an increasing fraction of thymic Treg with age (Thiault et al., 2015; Weist et al., 2015). To assess whether increased Treg cellularity in Ccr7−/− thymi was due to recirculation or de novo thymic Treg generation, we bred Ccr7−/− mice to a RAG2 promoter-driven GFP reporter strain (RAG2p-GFP), in which progressive loss of GFP signal after positive selection reflects the age of non-dividing thymocytes (Boursalian et al., 2004). CCR7 deficiency resulted in an increased percentage of GFP− Treg (GFP− CD25+CD4SP) that had recirculated into the thymus from the periphery. However, the percentage of newly generated Treg (GFP+ CD25+ CD4SP) did not increase (Figures S1B and C), consistent with a recent report (Cowan et al., 2016). These data indicate that increased thymic Treg cellularity in adult Ccr7−/− mice can be accounted for by enhanced recirculation of Treg into the thymus.

Because re-entered Treg suppress differentiation of new Treg in the thymus (Thiault et al., 2015), and because the number of Treg progenitors was elevated in Ccr7−/− mice (Figure 1C), we tested whether CCR7 deficiency altered Treg generation in the absence of Treg recirculation. First, we analyzed thymic Treg cellularity at postnatal day 4 (P4). The percent and number of FOXP3+CD25+ Treg and FOXP3+CD25− Treg progenitors were significantly increased in P4 Ccr7−/− thymi (Figures 1D–1F). Relative to the adult, there were very few splenic Treg at P4 available to recirculate to the thymus (Figure 1G), indicating that increased thymic Treg in Ccr7−/− mice reflected enhanced Treg generation. To determine whether CCR7 deficiency also enhances thymic Treg generation in the absence of recirculation in the adult, we transferred Ccr7+/+ or Ccr7−/− bone marrow into lethally irradiated Rag2−/− recipients, which are devoid of peripheral Treg. Thymic Treg chimerism was analyzed after 3 weeks, when the first wave of SP thymocytes had differentiated, but had not significantly emigrated to the periphery (Krueger et al., 2017; Serwold et al., 2009). We confirmed that there were few Treg in the periphery 3 weeks after transplantation (Figure S1D). Nonetheless, hematopoietic reconstitution of Rag2−/− recipients with Ccr7−/− bone marrow resulted in a higher percent of thymic Treg within the CD4SP compartment (Figure S1E). Furthermore, although there was a trend of decreased Treg cellularity in perinatal Ccr7−/− spleens, the fact that number of Treg in Ccr7−/− versus wild-type spleens was not statistically different in perinatal mice or reconstituted adults, indicates that Treg egress from the thymus was not impaired by CCR7 deficiency (Figures 1G and S1D), consistent with a previous report (Cowan et al., 2016). Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that CCR7 deficiency results in enhanced intrathymic Treg generation in perinates and bone-marrow reconstituted lymphopenic adults, when recirculating Treg are not present to suppress thymic Treg differentiation.

Increased thymic Treg cellularity in Ccr7−/− mice reflects a hematopoietic-intrinsic defect

To determine whether increased thymic Treg cellularity in Ccr7−/− mice reflected a defect in hematopoietic or non-hematopoietic cells, we generated reciprocal bone marrow chimeras using Ccr7+/+ and Ccr7−/− donor and recipient mice (Figure 2A). An increased proportion of Treg within the CD4SP compartment was observed only when donor cells were CCR7-deficient, regardless of the recipient genotype (Figure 2A). >80% of thymic Treg were of donor origin in bone marrow recipients (Figure S2), rather than of radio-resistant host origin (Komatsu and Hori, 2007). Thus, CCR7 deficiency in the hematopoietic compartment is necessary and sufficient for increased thymic Treg cellularity, consistent with expression of CCR7 by hematopoietic cells in the thymus (Förster et al., 2008; Ki et al., 2014).

Figure 2. The increased frequency of Treg cells in Ccr7−/− thymi is due to CCR7 deficiency in hematopoietic cells, but not to cell-intrinsic CCR7-deficiency in thymocytes.

(A) Quantification of the percent of FOXP3+ CD25+ Treg within the CD4SP compartment in the indicated reciprocal bone marrow chimera recipients. (B) Quantification of the percent of FOXP3+ CD25+ Treg within the CD45.1 or CD45.2 CD4SP compartments of the indicated competitive mixed bone marrow chimera recipients. Experiments were repeated twice with n = 6 total recipients per group. Graphs show data from a representative experiment. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM. * p<.05, ** p<.01. See also Figure S2.

Given that Treg and CD4SP cells, from which Treg are derived, both express CCR7 (Cowan et al., 2014), we hypothesized that increased Treg cellularity in Ccr7−/− thymi was due to a cell-autonomous defect in one of these subsets. To test this, we employed a competitive bone marrow chimera approach. CD45.1 Ccr7+/+ bone marrow cells were mixed with an equal number of CD45.2 Ccr7+/+ or CD45.2 Ccr7−/− bone marrow cells and transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1/CD45.2 recipients. If CCR7 deficiency in the T-lineage caused the increase in Treg cellularity, then Ccr7−/− CD4SP cells should yield a higher frequency of Treg. However, the percentage of Treg in the Ccr7−/− CD4SP compartment was comparable to controls (Figure 2B). Instead, wild-type hematopoietic cells yielded an increased percentage of Treg when mixed with CCR7-deficient cells, likely reflecting their competitive advantage in entering the medulla to encounter Treg niche factors (Weist et al., 2015). Together, these experiments show that increased thymic Treg cellularity reflected CCR7-deficiency in hematopoietic, but not T –lineage cells.

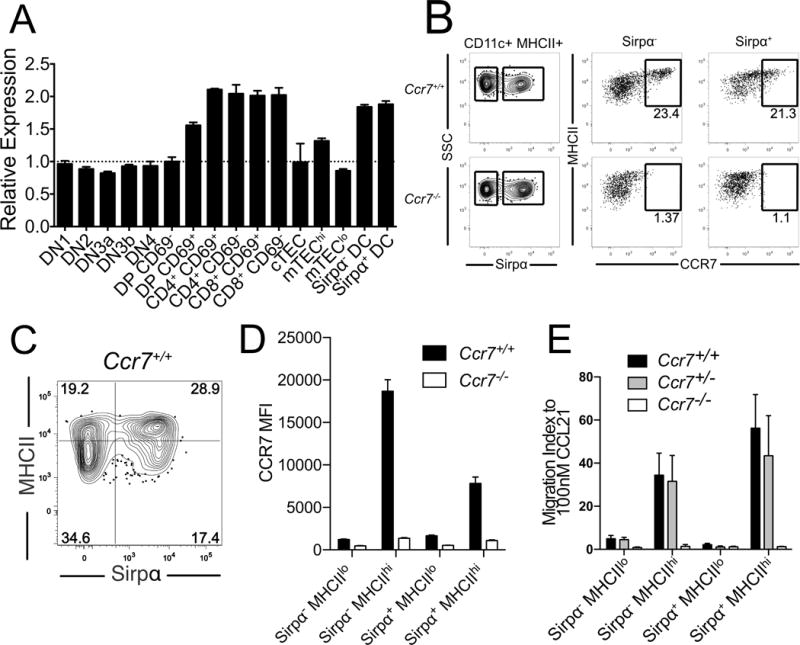

CCR7 is expressed by SP cells and DC in thymus

To identify the cell type responsible for increased Treg cellularity in Ccr7−/− mice, we examined expression of CCR7 by hematopoietic thymic subsets. Our previous expression profiling data showed that CCR7 was expressed by thymic CD4SP cells, CD8SP cells and DCs (Figure 3A) (Ki et al., 2014; Seita et al., 2012). Thymic DCs can be subdivided into pDC and two subsets of conventional DCs (cDCs), Sirpα− and Sirpα+. Both cDC subsets expressed cell-surface CCR7, which was upregulated with MHCII as DCs matured (Figure 3B), consistent with a recent report about Sirpα−DCs (Ardouin et al., 2016; Li et al., 2009). We therefore sub-divided cDCs into four subsets based on Sirpα and MHCII expression for further analysis (Figures 3C and S3). Flow cytometric analysis revealed that CCR7 was expressed only by mature MHCIIhi Sirpα− and MHCIIhi Sirpα+ DC subsets (Figure 3D). Thymic B cells, but not pDC, also expressed CCR7 (not shown). SP thymocytes and thymic DCs migrate towards CCR7 ligands (Campbell et al., 1999; Lei et al., 2011). In vitro chemotaxis assays revealed that MHCIIhi Sirpα− and MHCIIhi Sirpα+ DCs, which expressed CCR7, underwent chemotaxis towards the CCR7 ligand CCL21 (Figure 3E). These data demonstrate that CCR7 is expressed by and functional on mature MHCIIhi subsets of thymic cDCs.

Figure 3. CCR7 is expressed by mature thymic cDC and potentiates their chemotaxis towards CCR7 ligands.

(A) Relative levels of CCR7 expression by the indicated thymic cell types were quantified from transcriptional profiling data (Ki et al., 2014). (B) Representative flow cytometry plots display the bifurcation of thymic cDCs into Sirpα− versus Sirpα+ subsets (left) and the expression of CCR7 relative to MHCII on these two subsets (right) in Ccr7+/+ versus Ccr7−/− mice. (C) Representative flow cytometry plot showing the division of thymic cDC into four subsets, based on MHCII and Sirpα expression levels (see also Figure S3) (D) Expression level of CCR7 was quantified by flow cytometry, and the relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was determined for each DC subset. Data are compiled from 2 experiments with n = 6 mice per genotype. (E) Migration index of thymic cDC subsets responding to 100nM CCL21 in vitro. Data are compiled from 3 independent experiments with triplicate wells per experiment. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM.

Increased Treg cellularity correlates with CCR7 deficiency in thymic DCs rather than in thymic lymphocytes in vivo

Given expression of CCR7 by SP cells, B cells and DCs in the thymus, along with the finding that CCR7 impacts Treg generation in a hematopoietic, but non-T cell autonomous fashion, thymic B cells or DC are likely responsible for increased Treg cellularity in Ccr7−/− thymi. To test these possibilities, we established bone marrow chimeras in which lymphocytes and/or DC were CCR7-deficient, and then queried the frequency of Treg within the CD4SP compartment (Figure 4A). As controls, Ccr7+/+ or Ccr7−/− bone marrow was transferred into Ccr7+/+ recipients. In the Ccr7+/+ chimera, both lymphocytes and DCs were CCR7-sufficient, establishing a baseline frequency of Treg. As expected, in the Ccr7−/− chimera, in which both lymphocytes and DCs were CCR7-deficient, the frequency of Treg in the CD4SP compartment increased (Figures 4B and 4C).

Figure 4. Increased Treg generation correlates with CCR7 deficiency in the DC compartment, not alterations in thymic architecture.

(A) Schematic of the bone marrow chimera groups established to test whether CCR7 deficiency in lymphocytes versus DCs correlates with increased thymic Treg cellularity. Thymic chimerism was analyzed six weeks after transplantation. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the percent of Treg within the CD4SP compartment in the indicated chimeras. (C) Quantification of the percent of Treg within the CD4SP compartment of the indicated chimeras. Data are compiled from 3 experiments with n = 9 recipients per group. (D) Representative immunofluorescence staining (red: Keratin-5, green: pan-Keratin) of thymic sections from mice of the indicated chimeras. Scale bar: 1mm. (E–F) Quantification of (E) total medullary area and (F) percent of large medullary regions (>0.4mm2) from images as in D. Data for each group in E and F were compiled from a total of 6–9 sections taken from 2–3 mice per chimera group. Significance reflects comparison to Ccr7+/+ chimeras. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM. * p<.05, *** p< 0.001. See also Figure S4 and S5.

To distinguish between the effect of CCR7 deficiency on DCs versus lymphocytes, we capitalized on the fact that in Rag2−/− mice, DCs develop normally, while T and B cell development is blocked at an immature stage. We first confirmed that Rag2−/− bone marrow could efficiently give rise to thymic DCs, but not SP cells by transferring an equal mixture of CD45.2 Rag2−/− and CD45.1 Rag2+/+ bone marrow into irradiated recipients. Resultant thymic DCs were derived equally from both donors, while SP cells were derived only from the RAG2-sufficient donors (Figure S4). Next, we established bone marrow chimeras using a mixture of Ccr7+/+ and Rag2−/− bone marrow, in which both DCs and lymphocytes were CCR7-sufficient, but DCs were derived from both donors, whereas SP cells and B cells arose only from the Ccr7+/+ donor. In this control, the frequency of Treg was not altered relative to Ccr7+/+ chimeras, demonstrating that the presence of immature Rag2−/− thymocytes did not impact the frequency of Treg (Figures 4A–4C). In the experimental chimera, Rag2−/− and Ccr7−/− bone marrow cells were co-transferred. SP and B cells were CCR7 deficient in this chimera, as they could arise only from the Ccr7−/− donor. However, DCs were a mixture of CCR7-deficient and -sufficient cells as they could arise from both donors. Interestingly, the frequency of Treg in these chimeras was not elevated relative to controls (Figures 4A–4C). These results indicate that the presence of CCR7-sufficient DCs restored the frequency of Treg to normal levels, despite CCR7 deficiency in thymocytes and B cells. Thus, CCR7 deficiency in the DC compartment is necessary for the increased frequency of thymic Treg observed in Ccr7−/− mice.

Increased Treg cellularity is not due to altered thymic architecture

CCR7 deficiency results in altered thymic cortical: medullary organization, with small but numerous medullary regions (Ueno et al., 2004). Since the medulla is important for Treg generation (Coquet et al., 2013), altered medullary structure could impact Treg cellularity. Thus, we analyzed the thymic architecture in chimeras as in Figure 4A. Relative to chimeras in which the lymphocyte compartment was CCR7-sufficient, the medullary area was generally smaller in chimeras containing CCR7-deficient lymphocytes (Figures 4D–E), with a significant reduction in the percentage of large medullary regions (>0.4mm2) (Figures 4F). Since the frequency of Treg increased in Ccr7−/− chimeras, but not in Ccr7−/− + Rag2−/− chimeras (Figure 2A and Figure 4C), while the medullary area was reduced in both chimeras (Figures 4E and 4F), alterations in medullary size did not correlate with increased Treg frequencies.

We next determined whether CCR7 deficiency altered intrathymic DC localization or maturation of AIRE+ mTEC, both of which could impact Treg differentiation (Malchow et al., 2016; Proietto et al., 2008). In all chimera groups (Figure 4A), AIRE+ mTEC and DCs were present and localized properly in the medulla (Figure S5A and S5B). Taken together, these data indicate that CCR7-driven alterations in thymic DCs, rather than changes in thymic architecture, mTEC maturation, or DC localization, result in an increased frequency of Treg in Ccr7−/− mice.

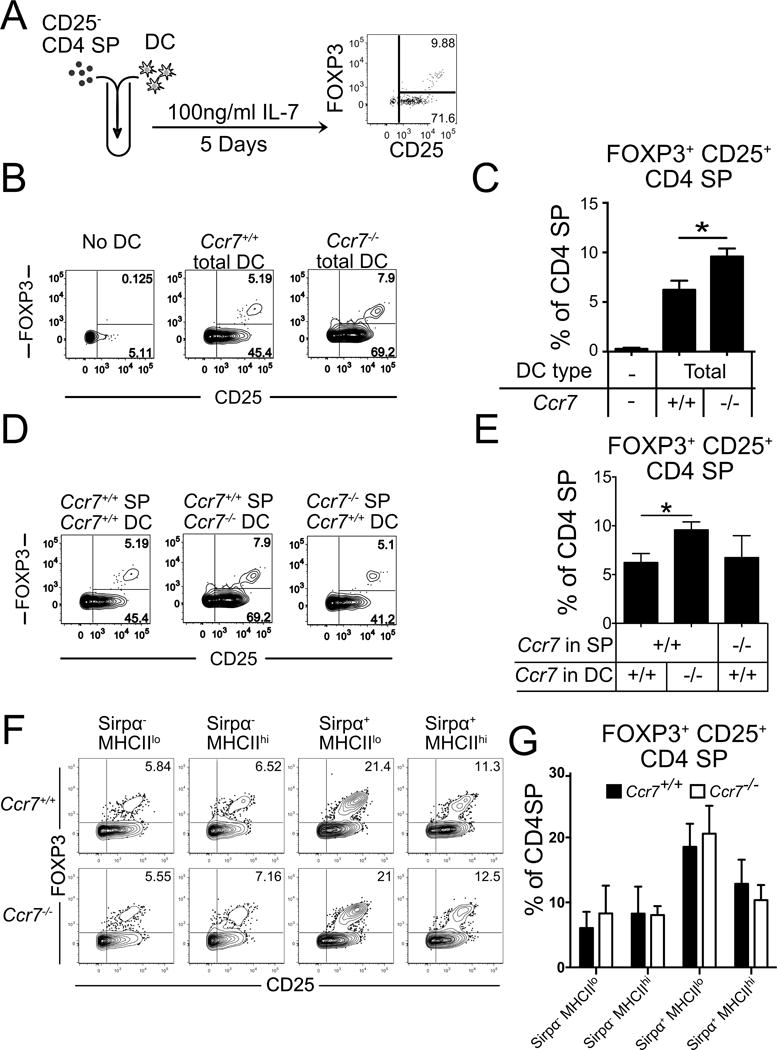

CCR7-deficient DCs efficiently induce Treg due to an increased proportion of immature Sirpα+ DC

To test whether Ccr7−/− thymic DCs could induce more Treg than Ccr7+/+ DCs, we utilized an in vitro Treg generation assay (Proietto et al., 2008). FACS purified DCs from Ccr7+/+ or Ccr7−/− thymi were co-cultured with Ccr7+/+ CD25− CD4SP cells for 5 days, and the number of Treg generated was quantified (Figure 5A). Notably, Ccr7−/− DCs induced more Treg than Ccr7+/+ DCs (Figures 5B and 5C). Using Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 reporter mice (Rubtsov et al., 2010), we repeated this assay with sorted eGFP−CD25−CD4SP cells to exclude all Treg progenitors, and confirmed that Ccr7−/− DCs induced the generation of more Treg (Figures S6A). We tested the reciprocal possibility that CCR7 deficiency in thymocytes could result in increased Treg generation when co-cultured with wild-type DC, but found that Ccr7−/− CD4SP did not generate more Treg than wild-type CD4SP. Only CCR7 deficiency in the DC compartment resulted in increased Treg generation (Figures 5D and 5E). These data demonstrate that Ccr7−/− DCs induce an increased number of Treg, but CCR7 deficiency in thymocytes does not directly impact Treg generation.

Figure 5. Ccr7−/− DC have a greater capacity to induce Treg.

(A) A schematic diagram of in vitro Treg generation assays. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots from Treg generation assays in which Ccr7+/+ CD25− CD4SP cells were co-cultured with thymic DC of the indicated genotypes. (C) Quantification of the percent of FOXP3+ CD25+ Treg within the CD4SP compartment from the indicated Treg generation assays as in B. A representative of 3 independent experiments is shown, with triplicate wells per condition. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of Treg generation assays in which Ccr7+/+ or Ccr7−/− CD25− CD4SP cells were co-cultured with Ccr7+/+ or Ccr7−/− total DC, as indicated. (E) Quantification of the percent of FOXP3+ CD25+ Treg within the CD4SP compartment from the indicated Treg generation assays as in D. A representative of 2 independent experiments is shown, with triplicate wells per condition. (F) Representative flow cytometric plots from Treg generation assays in which Ccr7+/+ eGFP− CD25− CD4SP were co-cultured with FACS purified thymic DC of the indicated subsets and genotypes. (G) Quantification of the percent of FOXP3+ CD25+ Treg within the CD4SP compartment from the indicated Treg generation assays, as in F. Data are compiled from 3 independent experiments, with triplicate wells per condition in each. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM. * p<.05. See also Figure S6.

To assess the mechanism by which CCR7 deficiency impacts the capacity of thymic DCs to induce Treg, we analyzed expression of molecules known to influence Treg generation. We did not observe differences in expression levels of MHCII, CD80, CD86, CD11c, CD40 or CD69 on Ccr7−/− versus Ccr7+/+ thymic cDC subsets. We did observe a slight increase in expression of CD69 on Ccr7−/− pDC (Figures S6B–D). Notably, EpCAM levels were significantly lower on Ccr7−/− Sirpα− DC (Figure S6C). Thymic DC acquire self-antigens from mTEC for presentation to thymocytes, and cell-surface EpCAM on DC reflects molecular transfer from mTEC (Koble and Kyewski, 2009). Thus, reduced EpCAM levels suggest that Ccr7−/− Sirpα− DC could be impaired in their capacity to acquire mTEC-derived antigens for presentation to thymocytes.

To test whether these subtle differences in expression could account for the increased capacity of Ccr7−/− DC to induce Treg, we performed Treg generation assays using eGFP−CD25−CD4SP cells from Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 reporter mice co-cultured with the four thymic cDC subsets, defined by MHCII and Sirpα levels as in Figure 3C, FACS purified from Ccr7−/− and Ccr7+/+ mice. None of the Ccr7−/− cDC subsets had a cell-intrinsic capacity to induce more Treg than their wild-type counterparts (Figures 5F and 5G). Therefore, altered expression profiles of Ccr7−/− DC subsets do not account for the enhanced capacity of the entire Ccr7−/− DC compartment to induce Treg. Interestingly, of the four cDC subsets, immature Sirpα+MHCIIlo DCs had the greatest capacity to induce Treg (Figure 5F and 5G). The Sirpα+MHCIIhi DC subset also induced more Treg than either Sirpα− subset (Figure 5F and 5G) or pDC (not shown), consistent with a previous report that Sirpα+DC induce Treg more efficiently than Sirpα−DC (Proietto et al., 2008).

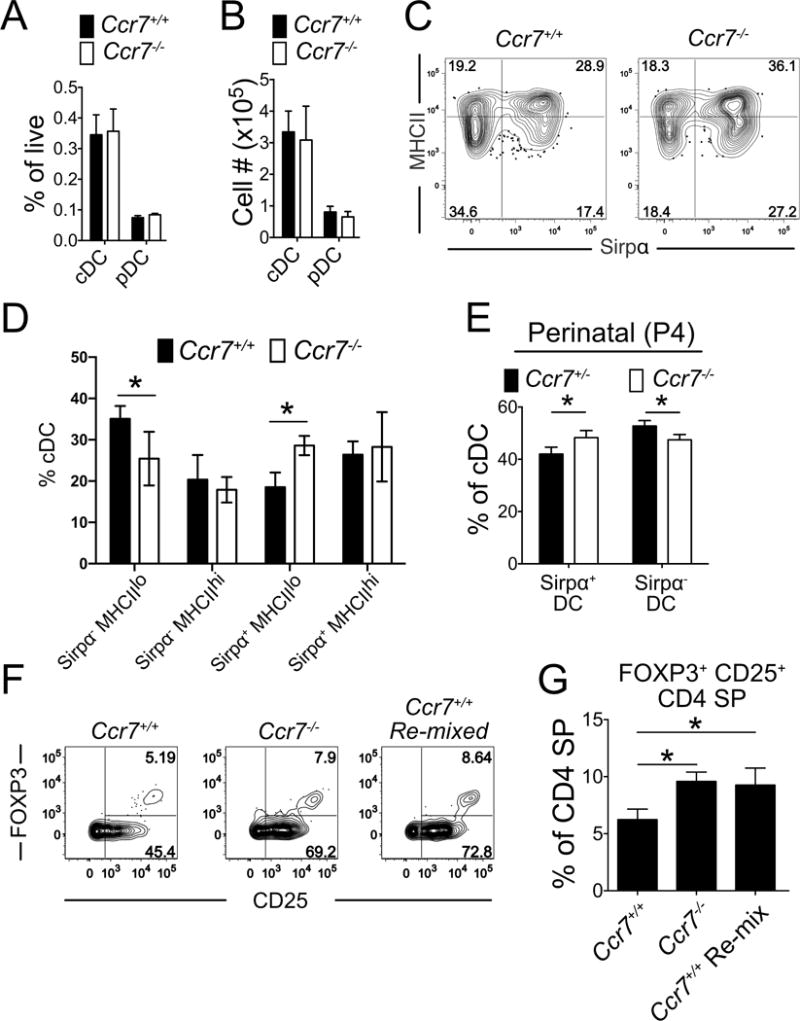

We next analyzed the composition of the thymic DC compartment in Ccr7−/− versus Ccr7+/+ mice. While there was no difference in the proportion or number of cDC or pDC (Figure 6A and 6B), the composition of the cDC compartment was altered in Ccr7−/− mice. The frequency of Sirpα+MHCIIlo DC was increased in adult Ccr7−/− mice (Figure 6C and 6D), mirrored by a decrease in the frequency of Sirpα− MHCIIlo DC. Importantly, the proportion of Sirpα+ DC was also expanded in perinatal p4 thymi from Ccr7−/− mice (Figure 6E). Since Sirpα+ DC have the greatest capacity to induce Treg (Figures 5F and 5G), their expansion in Ccr7−/− thymi could account for the increased capacity of the Ccr7−/− DC compartment to induce Treg. To test this hypothesis, we sorted DC subsets from Ccr7+/+ thymi, re-mixed them at the ratio observed in Ccr7−/− thymi, and performed a Treg generation assay. The re-mixed wild-type DCs had an increased capacity to generate Treg, comparable to Ccr7−/− DCs (Figures 6F and 6G). Together, these data indicate that the altered composition of the cDC compartment in Ccr7−/− mice, particularly the increased proportion of Sirpα+MHCIIlo DCs, is responsible for increased Treg generation.

Figure 6. An increased frequency of Sirpα+ DC in CCR7-deficient thymi results in increased Treg generation capacity.

(A–B) Quantification of the percent (A) and number (B) of cDC and pDC in adult Ccr7−/− or Ccr7+/+ thymi. Data are compiled from 3 experiments, with n = 8 mice per genotype. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the percent of the four cDC subsets in Ccr7+/+ versus Ccr7−/− thymi. (D) Quantification of the frequency of indicated cDC subsets in Ccr7+/+ or Ccr7−/− adult thymi. Data are compiled from 2 independent experiments, with n = 6 mice per genotype. (E) Quantification of the percent of Sirpα+ and Sirpα− DC within the cDC compartment of P4 mice. Data are compiled from 2 experiments, with n = 15 and mice n = 11 mice for the Ccr7+/− and Ccr7−/− groups, respectively. (F–G) Ccr7+/+ CD25− CD4SP were co-cultured with total Ccr7+/+ DC, Ccr7−/− DC or Ccr7+/+ Sirpα+ DC and Sirpα− DC remixed at the ratio found in Ccr7−/− thymi. (F) Representative flow cytometry plots from the indicated Treg generation assays. (G) Quantification of the percent of Treg from the experiment shown in F. Data are compiled from 2 experiments with 4 replicates per experiment. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM. * p<.05, *** p< 0.001.

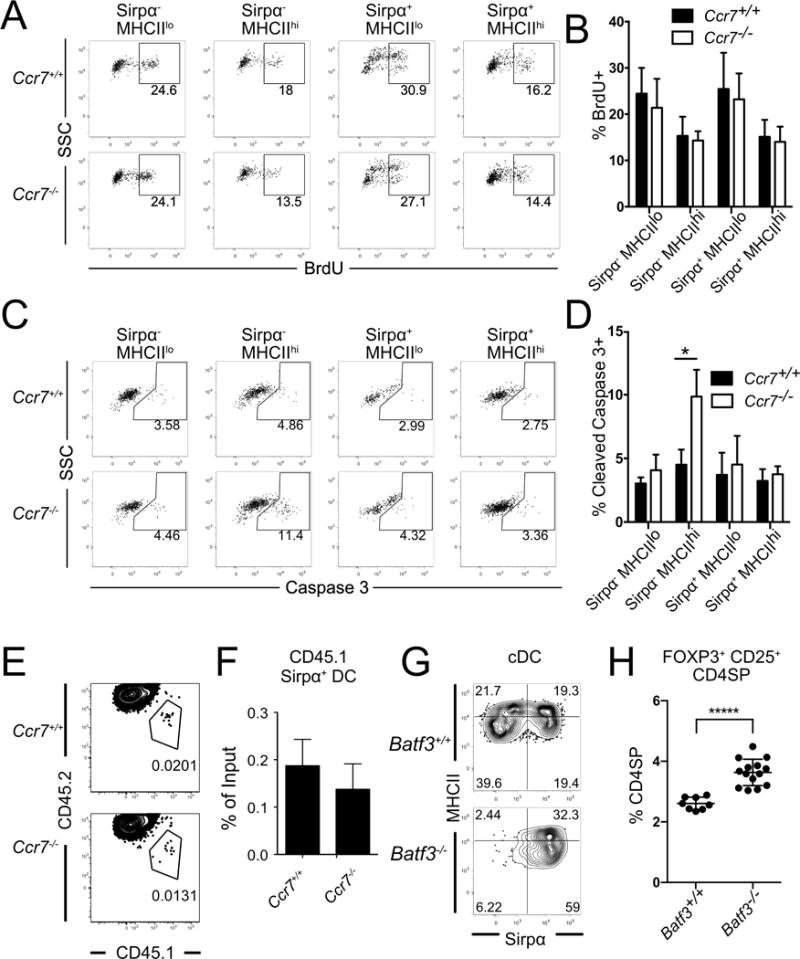

CCR7-deficient Sirpα− DC have an increased rate of apoptosis

We next investigated the mechanism by which CCR7 deficiency alters the composition of the thymic DC compartment. CCR7 deficiency did not impact the frequency of cells undergoing proliferation in any of the four cDC subsets (Figures 7A and 7B). However, a significantly greater proportion of Sirpα−MHCIIhi DCs underwent apoptosis in Ccr7−/− thymi (Figures 7C and D). Notably, this DC subset expresses the highest level of CCR7 (Figure 3B). CCR7 signaling has previously been shown to promote DC survival in secondary lymphoid organs (Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2004). These results reveal that CCR7 deficiency results in increased apoptosis of thymic Sirpα−MHCIIhi DCs, causing an imbalance in the frequency of cDC subsets in Ccr7−/− thymi.

Figure 7. CCR7 deficiency alters the composition of thymic cDC by inducing increased apoptosis of Sirpα−MHCIIhi DC.

(A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the percent of BrdU+ cells within the indicated thymic cDC subsets 24 hours after BrdU injection. (B) Quantification of the percent of BrdU+ cells from the experiments in A. Data are compiled from 3 independent experiments, with n =7 mice per genotype. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the percent of cleaved Caspase 3+ cells within the indicated cDC subsets. (D) Quantification of the percent of cleaved Caspase 3+ cells from experiments as in C. Data are compiled from 2 independent experiments with n = 6 mice per genotype. (E) Representative flow cytometry plots and (F) quantification of chimerism of CD45.1 Ccr7+/+ Sirpα+ DC that migrated into Ccr7+/+ or Ccr7−/− thymi 72 hours after i.v. transfer into recipient mice. Data are compiled from 2 experiments with a total of n =6 mice per genotype. (G) Representative flow cytometric plots showing the percent of the four cDC subsets in Batf3+/+ versus Batf3−/− thymi. (H) Quantification of the percent of FOXP3+ CD25+ Treg within the CD4SP compartment of thymi from Batf3+/+ versus Batf3−/− mice; n = 8 Batf3+/+ and n = 14 Batf3−/− mice. Graphs represent mean± SEM. * p<.05, ***** p<10−5.

Because Sirpα+MHCIIlo DC, which are over-represented in Ccr7−/− thymi, migrate into the thymus from circulation, we assessed whether CCR7 deficiency alters recruitment of Sirpα+ DC into the thymus. We first evaluated the relative thymic recruitment of Ccr7−/− versus Ccr7+/+ Sirpα+ DC into a wild-type thymus. White blood cells were isolated from CD45.1 Ccr7+/+ and CD45.2 Ccr7−/− mice, mixed at an equal ratio, and transferred intravenously into CD45.1/CD45.2 recipients. After three days, we could identify donor-derived Sirpα+ DC in recipient thymi; however, there was no preferential enrichment for Ccr7−/− Sirpα+ DCs (data not shown). We next tested whether CCR7-deficient thymi recruit an increased number of Sirpα+ DC. White blood cells from CD45.1 Ccr7+/+ mice were injected into CD45.2 Ccr7+/+ or CD45.2 Ccr7−/− mice. We found no evidence that Ccr7−/− thymi preferentially recruited the transferred Sirpα+ DC (Figures 7E and 7F). These data indicate that the increased frequency of Sirpα+ DC in Ccr7−/− thymi does not reflect changes in their rates of proliferation or apoptosis, or their preferential recruitment to the thymus. Because the total number of cDCs is not altered in Ccr7−/− thymi (Figure 6B), and a limiting thymic niche for DCs has been previously reported (Li et al., 2009), our data suggest that the increased apoptosis of Sirpα−MHCIIhi DC provides more niche space for Sirpα+MHCIIlo DC, creating an environment conducive for increased Treg generation. Factors regulating the DC niche remain to be defined.

To test our model that an increase in the frequency of Sirpα+DC results in an increased frequency of thymic Treg, we analyzed Batf3−/− thymi (Hildner et al., 2008), in which CD8+Sirpα− DC differentiation is impaired, resulting in an increased proportion of Sirpα+DC (Figure 7G). Consistent with our model, and in keeping with a recent study (Leventhal et al., 2016), we found that Batf3−/− thymi have an increased proportion of Treg (Figure 7H).

Discussion

Thymic Treg are comprised of two subsets: newly generated Treg that arise from CD4SP thymocytes and peripheral Treg that recirculate into the thymus (Thiault et al., 2015). Here, we demonstrate that CCR7 deficiency not only leads to a higher number of recirculating Treg, as previously reported (Cowan et al., 2016), but also to an increase in Treg generation in the perinatal period and during thymic rebound following bone marrow reconstitution in adults. We found that increased Treg frequency correlated with CCR7 deficiency in the thymic DC compartment. In keeping with this conclusion, DCs from Ccr7−/− thymi induced more Treg than wild-type DCs. CCR7 deficiency resulted in increased apoptosis of Sirpα−MHCIIhi DCs, with a concomitant increase in the proportion of immature Sirpα+ DC. Because these Sirpα+ DC have the greatest potential to induce Treg, skewing the DC compartment towards this subset increases Treg generation in Ccr7−/− thymi.

Our study raises the question of how immature Sirpα+ DC support such efficient Treg generation. Consistent with a previous study (Proietto et al., 2008), we found that Sirpα+DC express higher levels of MHCII and CD80 relative to Sirpα−DC (data not shown), suggesting they could induce potent TCR and co-stimulatory signaling. However, neither MHCII nor co-stimulatory molecules are expressed at high levels on immature Sirpα+ DC (data not shown). Another possibility is that Sirpα+ DC express high levels of CCR4 ligands (Hu et al., 2015b; Proietto et al., 2008). We previously reported that CCR4 expression on immature CD4SP thymocytes is required for efficient interactions with medullary DC (Hu et al., 2015b). Thus, MHCIIloSirpα+DC could induce Treg efficiently because of avid interactions with early-post positive selection thymocytes. It is also possible that MHCIIloSirpα+DC produce higher levels of common gamma chain cytokines, which are required for Treg differentiation and survival of FOXP3+CD25−, but not FOXP3−CD25+ Treg progenitors (Tai et al., 2013). Consistent with this possibility, the FOXP3+CD25−CD4SP cells were the only Treg progenitors with increased cellularity in perinatal Ccr7−/− mice. Future studies are needed to clarify mechanisms by which Sirpα+MHCIIlo DC efficiently induce Treg.

Treg generated during the perinatal period are critical for establishing and maintaining self-tolerance (Yang et al., 2015). The thymus also plays an essential role in selecting T cells that maintain self-tolerance after bone marrow transplantation (Guerau-de-Arellano et al., 2009). We found that Sirpα+DC were more abundant in perinatal Ccr7−/− mice, consistent with the observed increase in Treg generation. Since the TCR repertoire of Treg induced by Sirpα+ and Sirpα− DC do not fully overlap (Leventhal et al., 2016; Perry et al., 2014), Treg specificity in Ccr7−/− perinatal mice or adults recovering from bone marrow transplantation could be altered. Mature Sirpα−DC are specialized for presentation of AIRE-dependent antigens to thymocytes (Ardouin et al., 2016). Thus, the finding that acquisition of mTEC-derived antigens is impaired in CCR7-deficient Sirpα−MHCIIhi DC, as indicated by reduced EPCAM levels (Koble and Kyewski, 2009), further suggests that Treg selected by Ccr7−/− DC may have altered specificities. As Ccr7−/− mice are prone to autoimmunity (Kurobe et al., 2006), changing the Treg repertoire during this critical perinatal period or following transplantation could contribute to autoimmune susceptibility.

Elucidating the contributions of CCR7 deficiency in distinct cellular subsets to resultant autoimmunity is complicated by the numerous functions of CCR7. CCR7 governs trafficking of lymphocytes between and within primary and secondary lymphoid organs (Förster et al., 2008; Willimann et al., 1998; Yoshida et al., 1997). CCR7 promotes homing of thymocytes into the medulla (Ehrlich et al., 2009; Ueno et al., 2004), promotes homing of T cells, B cells and DC into lymph nodes (Cyster, 2005; Förster et al., 1999, 2008) and augments TCR signal transduction (Davalos-Misslitz et al., 2007b). CCR7 signaling promotes DC survival (Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2004) and maturation (Marsland et al., 2005). The migration of Treg is also controlled by CCR7 (Ishimaru et al., 2010; Nitta et al., 2009). Unlike naïve T cells, which fail to home to the LN in the absence of CCR7, CCR7-deficient Treg accumulate in secondary lymphoid organs (Schneider et al., 2007) because they fail to respond to S1P signals (Ishimaru et al., 2010, 2012). Interestingly, we and others find that egress of thymic Treg does not depend on CCR7 signaling (Cowan et al., 2016). Since the emigration of peripheral Ccr7−/− Treg from secondary lymphoid organs is impaired, additional experiments will be required to assess whether Treg generated in the context of Ccr7−/− DC mice have an altered capacity to suppress autoimmunity.

In Ccr7−/− thymi, both intrathymic Treg generation and recirculation from the periphery increase. In adult mice, increased thymic Treg cellularity was accounted for by increased recirculation of peripheral Treg. However, increased intrathymic generation of Treg occurred in perinatal mice and lymphopenic adults early after bone marrow reconstitution, when peripheral Treg were not available to recirculate to the thymus. Although the altered composition of thymic DC can account for increased Treg generation in Ccr7−/− mice, it is not fully understood why increased recirculation of peripheral Treg occurs in adult Ccr7−/− thymus. A previous study showed that increased recirculation is non-Treg intrinsic, as Ccr7+/+ Treg preferentially enter Ccr7−/− versus Ccr7+/+ thymi (Cowan et al., 2016). Our results show that although all Treg were CCR7-deficient in Ccr7−/− + Rag2−/− bone marrow chimeras, thymic Treg cellularity was not increased. Together, these results establish that CCR7 deficiency in Treg themselves does not account for increased recirculation to the thymus. There are several possible explanations: CCR7-deficient DC could provide altered signals to thymic stromal cells, such as TEC or endothelial cells, enhancing their capacity to recruit Treg into the thymus. Similarly, CCR7 is critical for entry of thymocyte seeding progenitors (Krueger et al., 2010; Zlotoff et al., 2010) and these CCR7-deficient progenitors could signal aberrantly to thymic stroma to increase recruitment of peripheral Treg. Alternatively, Ccr7−/− thymic DCs could support increased survival of recirculating Treg, perhaps through increased production of common gamma cytokines. Increased common gamma cytokine production by Ccr7−/− DC has the potential to reconcile enhanced Treg generation in perinates, with increased Treg recirculation in adults because Treg recruited to the thymus from the periphery suppress the generation of new Treg by sequestering IL-2 (Weist et al., 2015). Future studies are needed to resolve these possibilities.

Altogether, our studies identify an unanticipated contribution of CCR7 to thymic Treg differentiation. CCR7 expression by thymic DCs is required to maintain a physiologic balance of cDC subsets, and altering the balance of cDC subsets impacts Treg generation. As CCR7 deficiency causes alterations in thymic Treg generation during the perinatal period and during recovery from transplantation, our findings suggest that CCR7 is critical for normal generation of Treg that play a uniquely important role in maintaining self-tolerance.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

C57BL/6J (CD45.2), B6.SJL-PtprcaPepCb (CD45.1), B6(Cg)-Rag2tm1.1Cgn/J (Rag2−/−), B6.129S(C)-Batf3tm1Kmm/J (Batf3−/−), and B6.129P2(C)-Ccr7tm1Rfor/J (Ccr7−/−) mice were obtained from the Jackson laboratory (Bar Harbor). CD45.1/CD45.2 mice were bred in house. Rag2p-GFP mice were provided on the C57BL/6 background by Pamela Fink (UW, Seattle) and backcrossed to Ccr7−/− mice. Each experiment was performed using gender matched male or female mice 4–8 weeks of age, unless otherwise noted. Gender-specific differences were not observed. Mouse maintenance and experimental procedures were carried out with approval from UT Austin’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee or the University of Leuven animal ethics committee.

Generation and analysis of bone marrow chimeras

For competitive bone marrow chimeras, CD45.1/CD45.2 mice were lethally irradiated. 5×106 CD45.1 Ccr7+/+ and CD45.2 Ccr7−/− or CD45.2 Ccr7+/+ (C57BL/6J) T cell depleted bone marrow cells were mixed 1:1 and injected retro-orbitally into irradiated recipients. For reciprocal chimeras, Ccr7+/+ or Ccr7−/− T cell-depleted bone marrow cells were transplanted into Ccr7+/+ or Ccr7−/− irradiated recipients, as above. For Rag2−/− co-transfer experiments, irradiated Ccr7+/+ mice were reconstituted with either Ccr7+/+, Ccr7−/−, an equal mix of Rag2−/− and Ccr7+/+, or Rag2−/− and Ccr7−/− bone marrow cells, as above. After 6 weeks, thymocyte and Treg chimerism were assessed by flow cytometry (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures for detailed protocols and a list of antibodies used). For chimeras in the absence of recirculation, Ccr7+/+ and Ccr7−/− bone marrow cells were transferred into irradiated Rag2−/− mice, as above, and thymic chimerism was analyzed after 3 weeks.

Treg generation assay

Treg generation assays were carried out as previously described with modifications (Proietto et al., 2008). Briefly, 1 × 104 FACS sorted thymic DCs and 2 × 104 CD4+CD25− thymocytes from C57BL/6J mice or CD4+CD25−eGFP− thymocytes from Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 reporter mice were mixed in 200 l complete RPMI with 100 g/ml recombinant mouse IL-7 (eBioscience). Cells were co-cultured in round-bottom 96-well plates for 5 days, and were then analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

To test the impact of CCR7 deficiency on the cellularity of Treg or Treg progenitors in perinatal mice (Fig. 1 E–G), two-way ANOVA was performed using experimental date and CCR7 as the two factors to adjust for inter-experimental variation. Unpaired student’s t tests were used to calculate p-values for the remaining experiments. First, the F test was used to test the equal variance assumption between samples, and the appropriate t test was then used accordingly. When more than one statistical test was performed simultaneously, the Holm–Bonferroni multiple testing adjustment was used. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism (GraphPad).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

CCR7 deficiency results in increased thymic Treg generation and recirculation

Increased Treg generation is due to CCR7 deficiency in thymic dendritic cells

CCR7 promotes survival of thymic Sirpα− MHCIIhi dendritic cells

CCR7 regulates the composition of thymic DC to restrain Treg generation

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Salinas for technical assistance with cell sorting, and the staff at the University of Texas at Austin Animal Facility. We thank Simon Bornschein for preliminary experiments with Rag2-GFP mice and Pamela Fink for provision of Rag2p-GFP mice. This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (R1003; to L.I.R.E. and RR160005; to T.E.Y.), the National Institutes of Health/NIAID (R01AI104870; to L.I.R.E.) and the IAP (T-TIME; to A.L.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

Z.H. and Y.L. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. H.S., A.M.J., A.G.S, and T. E. Y. performed analysis of thymic architecture. A.v.N performed Treg in vitro suppression assays and analyzed Rag2-GFP mice. A.L. and L.E. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Anderson MS, Venanzi ES, Klein L, Chen Z, Berzins SP, Turley SJ, von Boehmer H, Bronson R, Dierich AA, Benoist C, et al. Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the Aire protein. Science (80–) 2002;298:1395–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1075958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardouin L, Luche H, Chelbi R, Carpentier S, Shawket A, Montanana Sanchis F, Santa Maria C, Grenot P, Alexandre Y, Grégoire C, et al. Broad and Largely Concordant Molecular Changes Characterize Tolerogenic and Immunogenic Dendritic Cell Maturation in Thymus and Periphery. Immunity. 2016;45:305–318. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano M, Toda M, Sakaguchi N, Sakaguchi S. Autoimmune disease as a consequence of develop- mental abnormality of a T cell subpopulation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:387–396. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbrenner K, D’Cruz LM, Vollmann EH, Hinterberger M, Emmerich J, Swee LK, Rolink A, Klein L. Selection of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells specific for self antigen expressed and presented by Aire+ medullary thymic epithelial cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:351–358. doi: 10.1038/ni1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, Brunkow ME, Ferguson PJ, Whitesell L, Kelly TE, Saulsbury FT, Chance PF, Ochs HD. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27:20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonasio R, Scimone ML, Schaerli P, Grabie N, Lichtman AH, Andrian UH von, von Andrian UH. Clonal deletion of thymocytes by circulating dendritic cells homing to the thymus. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1092–1100. doi: 10.1038/ni1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boursalian TE, Golob J, Soper DM, Cooper CJ, Fink PJ. Continued maturation of thymic emigrants in the periphery. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:418–425. doi: 10.1038/ni1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunkow ME, Jeffery EW, Hjerrild KA, Paeper B, Clark LB, Yasayko SA, Wilkinson JE, Galas D, Ziegler SF, Ramsdell F. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27:68–73. doi: 10.1038/83784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JJ, Pan J, Butcher EC. Cutting edge: developmental switches in chemokine responses during T cell maturation. J Immunol. 1999;163:2353–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquet JM, Ribot JC, Babala N, Middendorp S, van der Horst G, Xiao Y, Neves JF, Fonseca-Pereira D, Jacobs H, Pennington DJ, et al. Epithelial and dendritic cells in the thymic medulla promote CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development via the CD27-CD70 pathway. J Exp Med. 2013;210:715–728. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan JE, Parnell SM, Nakamura K, Caamano JH, Lane PJL, Jenkinson EJ, Jenkinson WE, Anderson G. The thymic medulla is required for Foxp3+ regulatory but not conventional CD4+ thymocyte development. J Exp Med. 2013;210:675–681. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan JE, McCarthy NI, Parnell SM, White AJ, Bacon A, Serge A, Irla M, Lane PJL, Jenkinson EJ, Jenkinson WE, et al. Differential Requirement for CCR4 and CCR7 during the Development of Innate and Adaptive αβT Cells in the Adult Thymus. J Immunol. 2014;193:1204–1212. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan JE, McCarthy NI, Anderson G. CCR7 Controls Thymus Recirculation, but Not Production and Emigration, of Foxp3+ T Cells. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyster JG. Chemokines, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:127–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos-Misslitz ACM, Rieckenberg J, Willenzon S, Worbs T, Kremmer E, Bernhardt G, Förster R. Generalized multi-organ autoimmunity in CCR7-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 2007a;37:613–622. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos-Misslitz ACM, Worbs T, Willenzon S, Bernhardt G, Förster R, Forster R. Impaired responsiveness to T-cell receptor stimulation and defective negative selection of thymocytes in CCR7-deficient mice. Blood. 2007b;110:4351–4359. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-070284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbinski J, Kyewski B. How thymic antigen presenting cells sample the body’s self-antigens. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich LIR, Oh DY, Weissman IL, Lewis RS. Differential Contribution of Chemotaxis and Substrate Restriction to Segregation of Immature and Mature Thymocytes. Immunity. 2009;31:986–998. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Müller I, Wolf E, Lipp M. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster R, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Rot A. CCR7 and its ligands : balancing immunity and tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:362–371. doi: 10.1038/nri2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerau-de-Arellano M, Martinic M, Benoist C, Mathis D. Neonatal tolerance revisited: a perinatal window for Aire control of autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1245–1252. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadeiba H, Lahl K, Edalati A, Oderup C, Habtezion A, Pachynski R, Nguyen L, Ghodsi A, Adler S, Butcher EC. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells transport peripheral antigens to the thymus to promote central tolerance. Immunity. 2012;36:438–450. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, Diamond M, Matsushita H, Kohyama M, Calderon B, Schraml BU, Unanue ER, Diamond MS, et al. Batf3 Deficiency Reveals a Critical Role for CD8 + Dendritic Cells in Cytotoxic T Cell Immunity. Science (80-) 2008;322:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Lancaster JN, Ehrlich LIR. The contribution of chemokines and migration to the induction of central tolerance in the thymus. Front Immunol. 2015a;6:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Lancaster JN, Sasiponganan C, Ehrlich LIR. CCR4 promotes medullary entry and thymocyte-dendritic cell interactions required for central tolerance. J Exp Med. 2015b doi: 10.1084/jem.20150178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert FXFX, Kinkel Sa, Davey GM, Phipson B, Mueller SN, Liston A, Proietto AI, Cannon PZF, Forehan S, Smyth GK, et al. Aire regulates the transfer of antigen from mTECs to dendritic cells for induction of thymic tolerance. Blood. 2011;118:2462–2472. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-286393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru N, Nitta T, Arakaki R, Yamada A, Lipp M, Takahama Y, Hayashi Y. In Situ Patrolling of Regulatory T Cells Is Essential for Protecting Autoimmune Exocrinopathy. 2010;5:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru N, Yamada A, Takahama Y, Hayashi Y. CCR7 with S1P 1 Signaling through AP-1 for Migration of Foxp3 ϩ Regulatory T-Cells Controls Autoimmune Exocrinopathy. AJPA. 2012;180:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MS, Boesteanu A, Reed AJ, Petrone AL, Holenbeck AE, Lerman MA, Naji A, Caton AJ. Thymic selection of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by an agonist self-peptide. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:301–306. doi: 10.1038/86302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ki S, Park D, Selden HJ, Seita J, Chung H, Kim J, Iyer VR, Ehrlich LIR, Ehrlich JI. Global transcriptional profiling reveals distinct functions of thymic stromal subsets and age-related changes during thymic involution. Cell Rep. 2014;9:402–415. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein L, Kyewski B, Allen PM, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: what thymocytes see (and don’t see) Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:377–391. doi: 10.1038/nri3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koble C, Kyewski B. The thymic medulla: a unique microenvironment for intercellular self-antigen transfer. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1505–1513. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu N, Hori S. Full restoration of peripheral Foxp3+ regulatory T cell pool by radioresistant host cells in scurfy bone marrow chimeras. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8959–8964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702004104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger A, Willenzon S, Lyszkiewicz M, Kremmer E, Forster R. CC chemokine receptor 7 and 9 double-deficient hematopoietic progenitors are severely impaired in seeding the adult thymus. Blood. 2010;115:1906–1912. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger A, Ziętara N, Łyszkiewicz M. T Cell Development by the Numbers. Trends Immunol. 2017;38:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurobe H, Liu C, Ueno T, Saito F, Ohigashi I, Seach N, Arakaki R, Hayashi Y, Kitagawa T, Lipp M, et al. CCR7-dependent cortex-to-medulla migration of positively selected thymocytes is essential for establishing central tolerance. Immunity. 2006;24:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y, Ripen AM, Ishimaru N, Ohigashi I, Nagasawa T, Jeker LT, Bosl MR, Hollander GA, Hayashi Y, Malefyt R de W, et al. Aire-dependent production of XCL1 mediates medullary accumulation of thymic dendritic cells and contributes to regulatory T cell development. J Exp Med. 2011;208:383–394. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal DS, Gilmore DC, Berger JM, Nishi S, Lee V, Malchow S, Kline DE, Kline J, Vander Griend DJ, Huang H, et al. Dendritic Cells Coordinate the Development and Homeostasis of Organ-Specific Regulatory T Cells. Immunity. 2016;44:847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Park J, Foss D, Goldschneider I. Thymus-homing peripheral dendritic cells constitute two of the three major subsets of dendritic cells in the steady-state thymus. J Exp Med. 2009;206:607–622. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston A, Lesage S, Wilson J, Peltonen L, Goodnow CC. Aire regulates negative selection of organ-specific T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:350–354. doi: 10.1038/ni906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchow S, Leventhal DS, Lee V, Nishi S, Socci ND, Savage Correspondence PA, Savage PA. Aire Enforces Immune Tolerance by Directing Autoreactive T Cells into the Regulatory T Cell Lineage. Immunity. 2016;44:1102–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland BJ, Battig P, Bauer M, Ruedl C, Lassing U, Beerli RR, Dietmeier K, Ivanova L, Pfister T, Vogt L, et al. CCL19 and CCL21 induce a potent proinflammatory differentiation program in licensed dendritic cells. Immunity. 2005;22:493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Gayo E, Sierra-Filardi E, Corbi AL, Toribio ML. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells resident in human thymus drive natural Treg cell development. Blood. 2010;115:5366–5375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menning A, H?pken UE, Siegmund K, Lipp M, Hamann A, Huehn J. Distinctive role of CCR7 in migration and functional activity of naive- and effector/memory-like Treg subsets. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1575–1583. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran AE, Holzapfel KL, Xing Y, Cunningham NR, Maltzman JS, Punt J, Hogquist KA. T cell receptor signal strength in Treg and iNKT cell development demonstrated by a novel fluorescent reporter mouse. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1279–1289. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta T, Nitta S, Lei Y, Lipp M, Takahama Y. CCR7-mediated migration of developing thymocytes to the medulla is essential for negative selection to tissue-restricted antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17129–17133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906956106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JSA, Lio CWJ, Kau AL, Nutsch K, Yang Z, Gordon JI, Murphy KM, Hsieh CS. Distinct Contributions of Aire and Antigen-Presenting-Cell Subsets to the Generation of Self-Tolerance in the Thymus. Immunity. 2014;41:414–426. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proietto AI, van Dommelen S, Zhou P, Rizzitelli A, D’Amico A, Steptoe RJ, Naik SH, Lahoud MH, Liu Y, ZHeng P, et al. Dendritic cells in the thymus contribute to T-regulatory cell induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19869–19874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810268105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubtsov YP, Niec RE, Josefowicz S, Li L, Darce J, Mathis D, Benoist C, Rudensky AY. Stability of the regulatory T cell lineage in vivo. Science. 2010;329:1667–1671. doi: 10.1126/science.1191996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon B, Lenschow DJ, Rhee L, Ashourian N, Singh B, Sharpe A, Bluestone JA. B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 2000;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Sánchez N, Riol-Blanco L, de la Rosa G, Puig-Kröger A, García-Bordas J, Martín D, Longo N, Cuadrado A, Cabañas C, Corbí A, et al. Chemokine receptor CCR7 induces intracellular signaling that inhibits apoptosis of mature dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;104:619–625. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MA, Meingassner JG, Lipp M, Moore HD, Rot A. CCR7 is required for the in vivo function of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:735–745. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seita J, Sahoo D, Rossi DJ, Bhattacharya D, Serwold T, Inlay MA, Ehrlich LIR, Fathman JW, Dill DL, Weissman IL. Gene Expression Commons: an open platform for absolute gene expression profiling. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwold T, Richie Ehrlich LI, Weissman IL, Ehrlich LI, Weissman IL. Reductive isolation from bone marrow and blood implicates common lymphoid progenitors as the major source of thymopoiesis. Blood. 2009;113:807–815. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai X, Erman B, Alag A, Mu J, Kimura M, Katz G, Guinter T, McCaughtry T, Etzensperger R, Feigenbaum L, et al. Foxp3 transcription factor is proapoptotic and lethal to developing regulatory T cells unless counterbalanced by cytokine survival signals. Immunity. 2013;38:1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiault N, Darrigues J, Adoue V, Gros M, Binet B, Perals C, Leobon B, Fazilleau N, Joffre OP, Robey EA, et al. Peripheral regulatory T lymphocytes recirculating to the thymus suppress the development of their precursors. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:628–634. doi: 10.1038/ni.3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno T, Hara K, Willis MS, Malin MA, Höpken UE, Gray DHD, Matsushima K, Lipp M, Springer TA, Boyd RL, et al. Role for CCR7 ligands in the emigration of newly generated T lymphocytes from the neonatal thymus. Immunity. 2002;16:205–218. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno T, Saito F, Gray DHD, Kuse S, Hieshima K, Nakano H, Kakiuchi T, Lipp M, Boyd RL, Takahama Y. CCR7 signals are essential for cortex-medulla migration of developing thymocytes. J Exp Med. 2004;200:493–505. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weist BM, Kurd N, Boussier J, Chan SW, Robey EA. Thymic regulatory T cell niche size is dictated by limiting IL-2 from antigen-bearing dendritic cells and feedback competition. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:2–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willimann K, Legler DF, Loetscher M, Roos RS, Delgado MB, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B. The chemokine SLC is expressed in T cell areas of lymph nodes and mucosal lymphoid tissues and attracts activated T cells via CCR7. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2025–2034. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199806)28:06<2025::AID-IMMU2025>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Shortman K. Heterogeneity of thymic dendritic cells. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Fujikado N, Kolodin D, Benoist C, Mathis D. Immune tolerance Regulatory T cells generated early in life play a distinct role in maintaining self-tolerance. Science. 2015;348:589–594. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa7017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida R, Imai T, Hieshima K, Kusuda J, Baba M, Kitaura M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Nomiyama H, Yoshie O. Molecular Cloning of a Novel Human CC Chemokine EBI1-ligand Chemokine That Is a Specific Functional Ligand for EBI1, CCR7. 1997;272:13803–13809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotoff DA, Sambandam A, Logan TD, Bell JJ, Schwarz BA, Bhandoola A. CCR7 and CCR9 together recruit hematopoietic progenitors to the adult thymus. Blood. 2010;115:1897–1905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.