Abstract

Objectives

To examine the impact of state/territory policy support on (1) uptake of evidence-based continuous quality improvement (CQI) activities and (2) quality of care for Indigenous Australians.

Design

Mixed-method comparative case study methodology, drawing on quality-of-care audit data, documentary evidence of policies and strategies and the experience and insights of stakeholders involved in relevant CQI programmes. We use multilevel linear regression to analyse jurisdictional differences in quality of care.

Setting

Indigenous primary healthcare services across five states/territories of Australia.

Participants

175 Indigenous primary healthcare services.

Interventions

A range of national and state/territory policy and infrastructure initiatives to support CQI, including support for applied research.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

(i) Trends in the consistent uptake of evidence-based CQI tools available through a research-based CQI initiative (the Audit and Best Practice in Chronic Disease programme) and (ii) quality of care (as reflected in adherence to best practice guidelines).

Results

Progressive uptake of evidence-based CQI activities and steady improvements or maintenance of high-quality care occurred where there was long-term policy and infrastructure support for CQI. Where support was provided but not sustained there was a rapid rise and subsequent fall in relevant CQI activities.

Conclusions

Health authorities should ensure consistent and sustained policy and infrastructure support for CQI to enable wide-scale and ongoing improvement in quality of care and, subsequently, health outcomes. It is not sufficient for improvement initiatives to rely on local service managers and clinicians, as their efforts are strongly mediated by higher system-level influences.

Keywords: continuous quality improvement, primary health care, health policy, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Using a mixed-method comparative case study methodology and drawing on data from 175 Indigenous primary healthcare services across Australia, we examine the impact of state/territory policy support and strategies on (1) uptake of CQI activities and (2) quality of care for Indigenous Australians.

Our analysis of several years of data from the largest and most comprehensive continuous quality improvement (CQI) programme in Australia shows that consistent and sustained policy and infrastructure support for CQI enables wide-scale and ongoing improvement in quality of care and, subsequently, health outcomes.

Our study adds to the accumulating evidence on the conditions that enable CQI efforts to be most effective.

The authors of this paper have all had longstanding involvement with a national CQI programme as researchers, service providers, managers or policy makers/advisors.

A limitation of our study is that it is not possible to clearly attribute the extent to which trends in data on quality of care have been influenced by various concurrent policy and other initiatives.

Introduction

Internationally, there is wide variation in adherence to best practice clinical guidelines between health services and between health professionals.1 There is a growing body of evidence about the effectiveness of continuous quality improvement (CQI) in increasing adherence to guidelines and on the factors that contribute to this.2 Variation in quality of care between health services has been demonstrated, including in populations with poorer health status, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (hereafter respectfully referred to as Indigenous) peoples in Australia.3 4

Indigenous people’s health and access to primary healthcare

Australia is a high-income country with gross disparities in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. This inequity has complex causes, including historical trauma and dispossession as a result of colonisation, social and economic conditions and persistent racism. While the Indigenous population is about 730 000 (3% of the Australian total), the numbers and proportion of the population vary widely between jurisdictions.5

Indigenous people access primary healthcare (PHC) through services specifically established to meet their needs—both community controlled and government managed—and private general practice.6

Positive policy environment

A recently proposed four-level framework to describe the causes of the ‘evidence–practice gap’7 backs up previous work that has called for change at multiple levels of the health system to support wide-scale improvement in the quality of care.8 While system-wide approaches to CQI have been associated with achieving large-scale improvements in health outcomes, there is limited evidence of the effectiveness of CQI over an extended period.2 A positive policy environment is widely recognised as vital for effective development and implementation of programmes to prevent and manage chronic disease,9 with previous cross-regional analyses identifying the importance of regional-level policies in enhancing clinical performance in Indigenous PHC in Australia.4 However, there is limited evidence as to the effect of government policy on the uptake and impact of CQI over time.

This paper examines the influence of health policy decisions at the Australian state/territory level and how these may have influenced: (i) trends in the consistent uptake of evidence-based CQI tools available through a research-based CQI initiative (the Audit and Best Practice in Chronic Disease (ABCD) programme) and (ii) quality of care (as reflected in adherence to best practice guidelines) in Indigenous PHC services.

National policy context: CQI in Indigenous PHC

The rapid growth since 2002 in CQI initiatives in Indigenous PHC has been supported to varying extents by several large-scale CQI programmes operating across a number of Australian states/territories, for example, the Australian Primary Care Collaboratives (APCC), Healthy for Life and the ABCD programme.10–12 As a programme of applied research, ABCD is the longest running and most extensively documented of these initiatives (box 1). To some extent, the Healthy for Life programme encouraged use of ABCD tools and processes by commissioning and promoting some of the audit tools in the programme. Similarly, engagement with APCC may have been a stimulus for services to explore the use of ABCD tools and processes and vice versa. In 2015, the Australian Government Department of Health provided funding for the development and implementation of a National CQI Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander PHC,10 which outlines roles and responsibilities for CQI at various levels of the system.

Box 1. The ABCD programme and continuous quality improvement tools.

The Audit and Best Practice in Chronic Disease (ABCD) programme is a continuous quality improvement (CQI) action research project that employed a systems approach to enhancing care delivered through Indigenous primary healthcare (PHC) services across Australia.3 16 17 Commencing in 2002, ABCD brought together service providers, policy makers and researchers in a collaborative programme of applied research, with the aims of developing and enhancing the feasibility of CQI tools and processes on a wide scale, examining factors associated with variation in quality of care and strategies that have been effective in improving quality of care and working together to enhance the implementation of effective strategies. We have previously reported on factors that influence variation in quality of care between health services11 and are engaged in an ongoing programme of research on priorities and strategies for improvement.13 Supported by a national CQI support entity (One21seventy), since 2010, more than 270 Indigenous PHC services have used standardised evidence-based best practice clinical audit and system assessment tools to assess and reflect on health service system performance, typically on an annual basis. The tools have been used to varying extent in all Australian states/territories. The distribution of PHC services and increase in engagement over time is depicted in figure 1.

CQI tools developed through the ABCD programme cover priority aspects of PHC (including preventive care, diabetes, child health and maternal health). The clinical audit tools were developed by expert working groups, with participation of specialists in relevant aspects of care and health service staff.3 The tools were designed to enable services to assess their work against best practice standards as reflected in widely accepted evidence-based guidelines; each tool is accompanied by an audit protocol. The ABCD audit tools are ideally used in a system-oriented collaborative and supportive CQI approach, together with an assessment of health service system performance conducted by health service staff in a facilitated group discussion using a standardised systems assessment tool.28 The evidence of effectiveness of the ABCD CQI process11 15 19–24 is consistent with international evidence of effectiveness of quality improvement strategies.2

Figure 1.

Distribution and use of ABCD programme continuous quality improvement tools in health services, over time, in 2007, 2011 and 2015.

The ABCD programme

For the duration of its operation, the ABCD programme has had a strong focus on both developing the evidence base for CQI in Indigenous PHC and supporting implementation of evidence-based CQI practices.3 13 14 The ABCD programme, and its associated service support arm One21seventy, have been used most extensively in the Northern Territory (NT) and Queensland (QLD) by both government and community-controlled Indigenous PHC services and to a lesser extent in New South Wales (NSW), South Australia (SA) and Western Australia (WA). The timing and nature of policy and funding support for ABCD and other CQI programmes has varied between jurisdictions. The most substantial support was available in NT and QLD and was generally of smaller scale and more fragmented in NSW, SA and WA.10 14 (box 1).

Methods

We use a comparative case study design to relate state/territory level policy support for CQI to trends in its uptake and in quality of care. The five states/territories provide the ‘cases’ for comparison as they all have some consistent CQI data available through participation by services in the ABCD programme.

Information on the use of CQI processes and tools and on policy and infrastructure support for CQI initiatives is drawn from publicly available sources. Information from these documentary sources is supplemented by the experience and insights of the authors, all of whom have been closely involved (including as service providers, managers, policy makers and advisors, CQI coordinators and researchers) over an extended period in relevant CQI programmes.

Data on CQI activity and on adherence to clinical best practice guidelines were available through ABCD. This paper focuses on four priority aspects of care: preventive, type 2 diabetes, maternal care and child health. The CQI and clinical record audit processes through which data are collected and reported at health service level are summarised in box 1 and online supplementary additional file 1 and described in more detail elsewhere.3 15

bmjopen-2017-016626supp001.pdf (419.5KB, pdf)

Outcome measures

For the purpose of assessing extent of CQI activity using ABCD standard tools, we sum the number of different audit tools used in each health service in each year for each jurisdiction.

We use a composite Quality of Care Index (QCI) to measure overall adherence to evidence-based clinical best practice guidelines in the delivery of care for each audit tool over successive years. The QCIs provide a measure of adherence to a package of evidence-based practices within each area of care. They therefore provide a more holistic measure of quality of clinical care (eg, overall delivery of type 2 diabetes care) than specific items of care (for example monitoring or control of HbA1c). We report on these QCIs for only NT and QLD, as these jurisdictions had data available from a large number of health services. QCIs were calculated by dividing the total number of client services for each client by the total number of possible services in the QCI.15 We use box plots to report QCIs for participating health services by jurisdiction for consecutive years and for consecutive audit cycles for health services that completed audits for at least three cycles (online supplementary additional file 2). Data on additional cycles are reported where there were data from at least half of the health services that completed audits in at least three cycles.

Statistical analysis

As the data have a hierarchical structure (patients within health services), mixed multilevel linear regressions were run to test the effect of jurisdictional location (NT and QLD) on service delivery (as measured by the QCI). Up to four audit cycles were included in the analysis where there were sufficient numbers of health services to enable cross-jurisdictional comparison. To minimise confounding, we confined analysis to health centres that completed the same number of audit cycles within each jurisdiction. The level of service delivery to individual clients (continuous variable: percentage of QCI delivered) was modelled with health service as an additional level random effect. Each model included adjustments for year of audit and audit cycle completed. Jurisdictional location (categorical) was included as a fixed effect. Variance partition coefficients were calculated to measure how much variability in adherence to best practice guidelines between health services was attributable to jurisdictional location. Inspection of residual plots showed no obvious deviations from normality or homoscedasticity. p Values were obtained by likelihood ratio tests of the model with jurisdictional location against the empty model without this effect. A p value ≥0.05 was considered statistically non-significant. Statistical analyses were conducted with STATA software, V.14.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for the ABCD National Research Partnership was obtained from research ethics committees in each relevant Australian jurisdiction.3

Findings

Policy initiatives that may have influenced uptake of the ABCD CQI programme, by state and territory

A number of national CQI initiatives may have influenced uptake of ABCD along with those being implemented simultaneously by the states/territories.10 12 An overview of CQI policy initiatives, by jurisdiction, showing the greatest uptake of the ABCD CQI tools is presented in summary form in table 1 and in more detail in online supplementary additional file 3.

Table 1.

Key policy and resourcing developments for CQI initiatives including ABCD 2005–2015

| National initiatives that supported CQI across multiple jurisdictions | |

| 2002–2006 | Continuous Improvement Projects |

| 2005–ongoing | Australian Primary Care Collaborative |

| 2005–ongoing | Healthy for Life programme—while not specifically a CQI programme, it did have a CQI component |

| 2010–2016 | One21seventy—National Centre for Quality Improvement in Indigenous Primary Healthcare |

| State and Territory programmes | |

| Northern Territory | |

| 2002–2005 | Government and ACCHO sectors supported CQI research through the original ABCD project |

| 2005–2009 | … and the ABCD Extension Project |

| 2009 | NT CQI Strategy endorsed by the Aboriginal Health Forum |

| 2012 | Wide-scale employment of CQI coordinators and facilitators to support PHC services across the NT |

| 2013 | External evaluation of the NT CQI investment |

| Queensland | |

| 2005–2006 | Review commissioned to identify best options for improving Indigenous health identifies CQI as a priority |

| 2007 | Development and implementation of CQI programme endorsed at senior government level |

| 2008 | Employment of CQI coordinators and facilitators to support PHC services across QLD |

| 2008 | North QLD Steering Committee established with key stakeholders, including Royal Flying Doctor Service, Apunipima Cape York Health Council and QLD Health |

| 2010 | … further major investment in CQI support—including contract with One21seventy to provide CQI support to services |

| 2010 | Peak community-controlled organisation implemented ‘collaborative-style’ CQI processes using electronic data extraction |

| 2011 | State-wide CQI Steering Committee established |

| New South Wales | |

| 2006 | NSW Health provided funding to the peak community-controlled organisation AH&MRC to support CQI among NSW ACHHS through building infrastructure, skills and data collection systems and to share models of good practice |

| 2010 | Several NSW Indigenous PHCs commenced use of ABCD CQI tools through contracts with One21seventy on their own initiative |

| 2015 | AH&MRC published CQI Success Stories from 10 ACCHSs |

| Western Australia | |

| 2005–2009 | WA Health provided funds for a CQI project officer to support ABCD programme in WA |

| 2006–2007 | Peak community-controlled organisation, AHCWA, conducted a pilot of the Australian Primary Care Collaborative in several ACCHSs |

| 2012–2015 | AHCWA Research Partnership on CQI |

| 2014 | Holman review recommended implementation of a state-wide CQI programme, with reference to One21seventy |

| 2014–2015 | AHCWA reported actively promoting CQI to all member services |

| South Australia | |

| 2008–2009 | Review of the evidence to support CQI conducted by South Australian health department |

| 2010–2014 | SA Health and Lowitja Institute provided funds for a CQI project officer to support ABCD programme in SA. Quality improvement officer based at peak community-controlled organisation supporting analysis and feedback to community-controlled health services in SA |

| Engagement with ABCD research in each state and territory | |

| Northern Territory | |

| 2002 | ABCD programme originated in 12 health services in the NT, building on prior work on chronic disease, best practice guidelines, clinical information systems in Indigenous PHC |

| 2005 | ABCD extension phase supported development of a CQI hub in Central Australia and Top End |

| 2011–2014 | All NT government health services and many ACCHS participated in the ABCD National Research Partnership, with the NT ABCD project officer supported by funding from NT Health |

| Queensland | |

| 2007–2008 | ABCD extension phase supported development of a CQI hub in QLD |

| 2011–2014 | All QLD Health services and several ACCHS participated in the ABCD National Research Partnership, with QLD ABCD project officer supported by funding from the Lowitja Institute |

| New South Wales | |

| 2005 | Maari Ma Health Aboriginal Corporation in far west NSW commenced with ABCD programme |

| 2011–2014 | Maari Ma Health Aboriginal Corporation participates in the ABCD National Research Partnership |

| Western Australia | |

| 2005 | ABCD extension phase supported development of a CQI hub in WA |

| 2011–2014 | Several ACCHS and WA health services participated in the ABCD National Research Partnership, with WA ABCD project officer supported by funding from the Lowitja Institute |

ABCD, Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease; ACCHO, Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organisation; ACCHS, Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Service; ACHSA, Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia; AH&MRC, Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council; AHCWA, Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia; CQI, continuous quality improvement; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; PHC, primary healthcare; QAIHC, Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council; QLD, Queensland; SA, South Australia; WA, Western Australia.

A total of 286 Indigenous PHC services used ABCD standard tools and reported data through the One21seventy web-based information system between 2005 and 2014. Of these health services, 175 voluntarily provided de-identified clinical audit data for analysis and reporting.

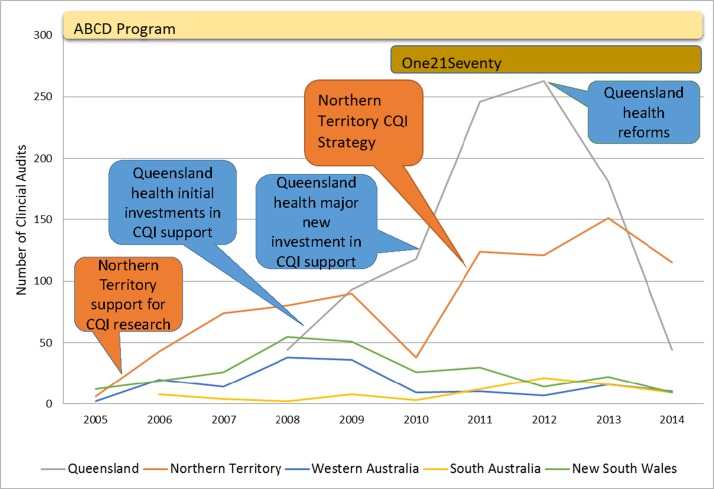

Northern Territory

The most substantial early uptake of the CQI tools was in the NT (table 1; figure 2; online supplementary additional file 3) where they were implemented in 12 health services following the first evidence of their success.3 There was a decline in the use of the tools in the NT in 2010, the final year of the extension phase of the ABCD research project, followed by a large increase in use the following year. This increase coincided both with the establishment of One21seventy as a service support agency for using ABCD CQI tools and processes and with the commencement of the NT CQI Strategy and corresponding funding support. The use of ABCD CQI tools plateaued over the period 2012–2014. An external evaluation commissioned by the NT government supported sustainability and embedding of processes.16

Figure 2.

Uptake of Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease (ABCD) continuous quality improvement (CQI) tools and major policy influences on trends in Northern Territory and Queensland.

Queensland

In QLD, use of the ABCD CQI tools commenced in 2007/8, with the engagement of QLD Health and some community-controlled PHC services (largely in the north of the state) in the ABCD programme (table 1; figure 2; online supplementary additional file 3). This followed an internal review of evidence on improving healthcare delivery and subsequent recommendations to increase investment in CQI in 2008 and again in 2010. There was a rapid increase in the use of the tools to a peak in 2011 and 2012, following the second investment by QLD Health in CQI coordinators and facilitators and in supporting health services to access ABCD tools and the One21seventy web-based information system. There was a marked decline in the use of the ABCD CQI tools in 2013 and 2014, following the change in government in 2012, a lack of policy support and cuts in funding.

New South Wales

Use of the ABCD CQI tools in NSW peaked in 2008 and 2009 but declined as the state’s early leading exponent of CQI, Maari Ma Health Aboriginal Corporation in Broken Hill, shifted attention to using the ABCD audit tools in selected aspects of clinical care and applying CQI techniques to the management of various organisational systems and processes (table 1; figure 2; online supplementary additional file 3). There was some continuing use of ABCD CQI tools in Maari Ma Health and in other NSW services despite the absence of direct support for the use of these tools from NSW health authorities.

Western Australia

In WA, use of the ABCD CQI tools increased from 2005 to a peak in 2008 and 2009 across several health services (table 1; figure 2; online supplementary additional file 3). The decline in usage coincided with the end of ABCD’s extension phase, but a number of health services continued to use the tools despite relatively limited engagement with ongoing research and no direct support from WA health authorities.

South Australia

A small number of services used the ABCD CQI tools in SA between 2006 and 2010 and slightly more between 2011 and 2014—the increase coinciding with provision of limited funding and policy support from research and SA health (table 1; figure 2; online supplementary additional file 3). This policy support occurred after an internal review (similar to QLD) on the evidence and best options to improving delivery of care.

Trends in quality of care

The QCIs of adherence to best practice guidelines for health services in the NT generally show improvement over audit cycles and over successive years. More specifically, between audit cycles 1 and 4, the median % of services delivered for participating health centres increased by more than 25% for overall preventive care and by about 10% for overall type 2 diabetes care and overall child healthcare (online supplementary additional file 2; table 2). There was also improvement in the median % of services delivered in successive years for all four areas of care. The improvement in NT is accompanied by a reduction in variation between health services for preventive care and child health QCIs, due to improvement among poorer-performing health services.

Table 2.

Summary of care quality trends over years and CQI cycles in Northern Territory and Queensland

| Area of Care | Trend over time | Trend over CQI cycles | Variation over CQI cycles |

|||

| NT | QLD | NT | QLD | NT | QLD | |

| Diabetes | ↑ | ~ | ↑ | ~ | * | ~ |

| Preventive | ↑ | ~ | ↑ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Child | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Maternal | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | * | ~ |

Legend: (↑) improvement, (~) no change, (↓) decrease, (*) reduced variation.

CQI, continuous quality improvement; NT, Northern Territory; QLD, Queensland.

See online supplementary additional file 2 for more detailed data.

In QLD, the QCIs of adherence to best practice guidelines show a mixed picture. There was improvement in the median % of services delivered for participating health services between audit cycles 1 and 4 of about 15% for overall antenatal care. For overall type 2 diabetes care and overall preventive care, there was an increase in the median % of services delivered of about 10% and 5%, respectively, between audit cycles 1 and 3, followed by a decline at audit cycle 4 (online supplementary additional file 2; table 2). There was no clear trend for diabetes care over successive years or over audit cycles or for preventive care over time. There was a declining trend over successive years and no clear increasing or decreasing trend over audit cycles for child health. Nor was there a clear reduction in variation between health services in any of the four areas of care over time or over audit cycles.

The multilevel linear regression analyses showed that there was a significant difference between the two jurisdictions for preventive and diabetes care. After adjusting for year of audit and number of cycles completed, the predicted increase in adherence to best practice for NT compared with QLD health services was 12% (95%CI 5.61 to 17.70; p<0.0001) and 16% (95%CI 11.87 to 19.58; p<0.0001) for preventive and diabetes care, respectively. Jurisdictional location accounted for 17% and 18.2% of the explained variability in adherence to best practice guidelines for both. There was no significant difference between jurisdictions in relation to child or maternal care (table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated effect of jurisdictional location on care quality (% increase in services) for each area of care: Northern Territory compared to Queensland

| Preventive health (n=75 services; 9627 audit records) | Type 2 diabetes (n=95; 10 103) | |||||

| Coefp | p Value | 95% CIs | Coef | p Value | 95% CIs | |

| Audit year | 4.23 | <0.0001 | (3.22 to 5.23) | 2.44 | <0.0001 | (1.84 to 3.04) |

| Audit cycle | −1.14 | 0.08 | (−2.43 to 0.15) | 0.64 | 0.12 | (−0.17 to 1.45) |

| Jurisdiction (QLD reference) | 11.66 | <0.0001 | (5.61 to 17.70) | 15.73 | <0.0001 | (11.87 to 19.58) |

| LRTest χ2 (1df) | 13.65 | (p=0.0002) | 50.13 | (p<0.0001) | ||

| VPC | 17.0% | 18.2% | ||||

| Child health (n=74; 6724) | Maternal health (n=38; 2180) | |||||

| Coef | p Value | 95% CIs | Coef | p Value | 95% CIs | |

| Audit year | 0.67 | 0.28 | (−0.53 to 1.87) | −0.97 | 0.025 | (−1.82 to 0.12) |

| Audit cycle | 0.74 | 0.37 | (−0.89 to 2.36) | 6.10 | <0.0001 | (4.78 to 7.42) |

| Jurisdiction (QLD reference) | 4.98 | 0.07 | (−0.42 to 10.38) | −2.38 | 0.27 | (−6.59 to 1.83) |

| LRTest χ2 (1df) | 3.22 | (p=0.07) | 1.22 | (p=0.27) | ||

| VPC | 15.0% | 16.6% | ||||

As measured by the Quality of Care Index.

Coef, coefficient; LRTest, likelihood ratio test; QLD, Queensland; VPC, variance partition coefficient.

Discussion

Progressive and sustained uptake of ABCD tools occurred in the NT in the context of consistent long-term policy and infrastructure support for CQI. This contrasted with (a) a rapid rise and subsequent fall in uptake of these tools in QLD where the initial high-level policy and infrastructure support was not sustained following a change of government in 2012 and (b) low levels of uptake in jurisdictions with relatively less policy and infrastructure support (NSW, WA, SA). The consistent long-term policy and infrastructure support for CQI in the NT was also associated with steady improvements or maintenance of high-quality care (as reflected in clinical best practice guidelines) for the four aspects of care that were the major focus of ABCD CQI efforts and reduction in variation between health services for two of these. This contrasted with the situation in QLD where there was a relatively limited effect on adherence to best practice guidelines and on variation between health services.

While this study does not provide an in-depth examination of the complex processes that might explain different trends in the uptake of tools or how CQI processes have impacted on quality of care in different jurisdictions, some insight has been provided by previous studies of the ABCD CQI programme11 15–24 and the evaluation of the NT CQI Strategy.18 Gardner et al highlighted the complexity of the process of uptake of CQI and the critical role of alignment of policies and incentives, a systems approach, organization-wide commitment, leadership at all levels and resources to support implementation.19 Our findings of relatively low uptake of CQI in jurisdictions with limited policy and infrastructure support and the rapid drop in use of CQI tools when policy, infrastructure and funding support was withdrawn in QLD highlight the critical role these play in supporting its uptake. In these states, the lack of clear and consistent policy direction, resourcing and sustained high-level leadership and management support for CQI and relative lack of engagement in wide-scale CQI research have led to a diversity of locally driven initiatives with an associated lack of systematic analysis and reporting of data for CQI purposes. This appears to have been a barrier to demonstrably effective uptake of CQI in many Indigenous PHC services between 2005 and 2014.

The limited availability of data for systematic analysis and reporting of relevant data, other than in QLD and NT, has precluded meaningful analysis of adherence to best practice guidelines for most states/territories. The first report on national Key Performance Indicators (nKPIs) from Indigenous PHC organisations showed that, in 2012–2013, those in QLD and the NT performed better against almost all process-of-care indicators,25 attributing this to the relatively well-established CQI programme in these jurisdictions. The third and most recent nKPI report, which includes data up to December 2014,26 shows improvements for 17 of the 19 process-of-care measures for all jurisdictions combined, with continued relatively high performance in NT and QLD and most marked recent improvement in WA. The analysis presented in this paper points to the importance of high-level policy support and resourcing for implementation of systematic CQI processes to enhance quality of care. The relatively high performance and the greater ability to report nKPI data in NT and QLD demonstrate the benefits of systematic CQI processes for reporting of data on KPIs as well as for enhancing quality of care.

The independent evaluation of the NT CQI Strategy provides important insights into the relative success of CQI initiatives in the NT. There has been no comparable publicly available independent evaluation in QLD, NSW, WA or SA, and it may be that an external evaluation such as that of the Strategy plays a role in ensuring sustainability and momentum. The formalised collaborative engagement of the community-controlled and government sectors in the NT through the Aboriginal Health Forum and the shared commitment and enthusiasm for a territory-wide CQI Strategy have also contributed to the achievements in the NT. Given the importance of working effectively together to respond to the complex care needs of Indigenous patients, it appears that a partnership approach adopted across service sectors is a critical component underpinning efforts in improving quality of care.

Another important component has been the adaptation of collaborative methods to sustain the engagement of experienced front-line service providers and managers, such as bringing them together to share learnings. Together with sustained investment, the shared commitment and enthusiastic engagement in CQI in NT is likely to have engendered the sense of collective efficacy and collective valuing of CQI data that has led to the effectiveness of CQI.11

An important limitation of our study is that it is not possible to determine clearly the extent to which trends in data on quality of care have been influenced by policy support for the ABCD CQI programme or to other initiatives (eg, funding, workforce or infrastructure developments). The difficulty of demonstrating causality is common to much policy research27; however, we argue here for contribution rather than attribution. Improvements to the quality of care in NT built on substantial earlier initiatives, including electronic patient information record systems, the development and implementation of a Chronic Disease Strategy and sustained commitment to workforce development.

The ABCD data are not representative of all Indigenous PHC services. There was variable participation in different jurisdictions and by government-operated and community-controlled health services. For example, in the NT, there were substantial numbers of both service types participating in ABCD, but relatively low numbers of community-controlled services in QLD. The ABCD data need to be interpreted in relation to a range of other CQI activities in Indigenous PHC services over the period for which data have been reported.10 12 While there were some substantial initiatives, particularly in NT and QLD, most CQI initiatives were small scale, narrow in scope and without the capability to analyse and report consistent data to the extent possible through ABCD. Nor has it been possible to assess systematically these CQI activities or their impact on quality of care. In addition, there were a range of non-CQI initiatives at the national (eg, Indigenous Chronic Disease Package)28 and local levels, which may have impacted on quality of care over the period for which we have reported data. More generally, as with all research of this type, it is vital to consider historical, socioeconomic and health service and system contexts in assessing the generalisability or transferability of the findings to other PHC settings in Australia or internationally.

The authors of this paper have all had longstanding involvement with the ABCD programme as researchers, service providers, managers or policy makers/advisors. While our interest in ABCD may have influenced our interpretation of the data, the diversity of roles, insights and perspectives that we bring allows for critical reflection in the interpretation of the data and brings rigour to this type of research.27

The ABCD experience, as reflected in this paper, has important implications for practice, policy and further research, including the implementation of the National CQI Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander PHC.10 For clinical staff and management of health services, the benefits of participating in this type of collaborative programme include access to a CQI system that provides data on recent performance and trend data across the broad scope of primary care and the ability to benchmark against other services at the regional, state/territory and national level. For policy professionals, benefits include the ability to monitor adherence to best practice guidelines at all levels and to target improvements to specific aspects or modes of care,24 population groups (eg, children or the elderly) or geographic locations. An important challenge for ongoing and new CQI initiatives is to enhance local ownership and engagement, while ensuring the use of standard tools and supporting the analytical capability that enables the use of consistent good-quality data for CQI purposes at multiple levels of the system. Sustaining efforts to deliver the best care according to changing evidence over time remains important and warrants further attention.

Conclusion

Our study adds to the accumulating evidence on the conditions that enable CQI efforts to be most effective. The findings show the potential contribution that systematic and sustained policy and infrastructure support can make to wide-scale uptake and to the effectiveness of CQI methods in improving the quality of care. It is now about 10 years since our first published paper on the potential for CQI to enhance the quality of healthcare for Indigenous Australians. With the development of a National CQI Framework in 2015,10 it appears we may be at the dawn of a new era of wide-scale and systematic use of CQI methods. While local efforts are vital to the effective use of CQI methods, state/territory-level policy and resources will be critical to building capability and a supportive environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The development of this manuscript would not have been possible without the active support, enthusiasm and commitment of staff in participating primary health care services and members of the ABCD National Research Partnership and the Centre for Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement.

Footnotes

Contributors: RB conceived and had the primary role in drafting of the manuscript. VM undertook the quantitative data analysis and had a major role in drafting and review. All other authors (SL, ST, CP, TW, JB, FC, RK, LC) played substantial roles in providing information on QI initiatives in various states and territories, in analysis and interpretation of data and review of successive drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The National Health and Medical Research Council has funded the Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease National Research Partnership Project (#545267) and the Centre for Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement (#1078927). In-kind and financial support has been provided by the Lowitja Institute and a range of community-controlled and government agencies.

Competing interests: RB was the scientific director of One21seventy, a not-for-profit entity within Menzies School of Health Research that provided CQI support on a fee-for-service basis to primary healthcare services across Australia. RB is also the lead investigator on the Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease research programme, and other authors are co-investigators. None of the authors received financial support from One21seventy, and One21seventy did not provide any financial support for the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no other competing interests in the preparation of this manuscript.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from research ethics committees in each jurisdiction (Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (HREC-EC00153); Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC-12-53); New South Wales Greater Western Area Health Service Human Research Committee (HREC/11/GWAHS/23); Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee Darling Downs Health Services District (HREC/11/QTDD/47); South Australian Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee (04-10-319); Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HR140/2008); Western Australian Country Health Services Research Ethics Committee (2011/27); Western Australia Aboriginal Health Information and Ethics Committee (111-8/05); University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (RA/4/1/5051)).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease dataset analysed during the current study is not publicly available due to health centre confidentiality but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and if consistent with the project’s ethics approvals.

References

- 1. Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet 2003;362:1225–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tricco AC, Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, et al. . Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;379:2252–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60480-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bailie R, Si D, Shannon C, et al. . Study protocol: national research partnership to improve primary health care performance and outcomes for Indigenous peoples. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:10 1. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Si D, Bailie R, Dowden M, et al. . Assessing quality of diabetes care and its variation in Aboriginal community health centres in Australia. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2010;26:464–73. 10.1002/dmrr.1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Health and Welfare of Australia’s aboriginal and torres strait islander peoples 2015. Cat. no. IHW 147. Canberra: AIHW, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bailie J, Schierhout G, Laycock A, et al. . Determinants of access to chronic illness care: a mixed-methods evaluation of a national multifaceted chronic disease package for Indigenous Australians. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008103 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, et al. . Achieving change in primary care—causes of the evidence to practice gap: systematic reviews of reviews. Implement Sci 2016;11:1 10.1186/s13012-016-0396-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q 2001;79:281–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Epping-Jordan J, Pruitt S, Bengoa R, et al. . Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. Qual Safety Health Care 2004;13:299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lowitja Institute. Draft Final Report: Recommendations for a National CQI Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care. Canberra: Prepared for the Commonwealth Department of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schierhout G, Hains J, Si D, et al. . Evaluating the effectiveness of a multifaceted, multilevel continuous quality improvement program in primary health care: developing a realist theory of change. Implement Sci 2013;8:119 10.1186/1748-5908-8-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wise M, Angus S, Harris E, et al. ; Appraisal of Continuous Quality Improvement Initiatives in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care. Melbourne: Prepared for the Lowitja Institute, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Laycock A, Bailie J, Matthews V, et al. . Interactive dissemination: engaging stakeholders in the use of aggregated quality improvement data for system-wide change in Australian Indigenous primary health care. Front Public Health 2016;4 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cunningham FC, Ferguson-Hill S, Matthews V, et al. . Leveraging quality improvement through use of the Systems Assessment Tool in Indigenous primary health care services: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:583 10.1186/s12913-016-1810-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matthews V, Schierhout G, McBroom J, et al. . Duration of participation in continuous quality improvement: a key factor explaining improved delivery of type 2 diabetes services. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:1):1 10.1186/s12913-014-0578-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bailie R, Matthews V, Brands J, et al. . A systems-based partnership learning model for strengthening primary healthcare. Implement Sci 2013;8:143 10.1186/1748-5908-8-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bailie J, Schierhout G, Cunningham F, et al. . Quality of PHC for aboriginal and torres strait islander people in Australia. Key research findings and messages for action from the ABCD National Research Partnership Project. Brisbane: Menzies School of Health Research, 2015. http://apo.org.au/system/files/55532/apo-nid55532-14486.pdf (accessed 21 Jun 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Allen and clark. Evaluation of the Northern Territory CQI Investment Strategy. Canberra: Department of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gardner KL, Dowden M, Togni S, et al. . Understanding uptake of continuous quality improvement in Indigenous primary health care: lessons from a multi-site case study of the Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease project. Implement Sci 2010;5:1 10.1186/1748-5908-5-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bailie C, Matthews V, Bailie J, et al. . Determinants and gaps in preventive care delivery for Indigenous Australians: a cross-sectional analysis. Front. Public Health 2016;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Larkins S, Woods CE, Matthews V, et al. . Responses of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health-care services to continuous quality improvement initiatives. Front. Public health 2015;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gibson-Helm ME, Rumbold AR, Teede HJ, et al. . Improving the provision of pregnancy care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women: a continuous quality improvement initiative. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:1 10.1186/s12884-016-0892-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vasant B, Matthews V, Burgess C, et al. . Wide variation in absolute cardiovascular risk assessment in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with type 2 diabetes. Front. Public Health 2016;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schierhout G, Matthews V, Connors C, et al. . Improvement in delivery of type 2 diabetes services differs by mode of care: a retrospective longitudinal analysis in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care setting. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:560 10.1186/s12913-016-1812-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Key Performance Indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care: first national results June 2012 to June 2013. National key performance indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care series. Cat no. IHW 123. Canberra: AIHW, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Key Performance Indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care: results from December 2014. National key performance indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care series no.3. Cat. no. IHW 161. Canberra: AIHW, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walt G, Shiffman J, Schneider H, et al. . ’Doing' health policy analysis: methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy Plan 2008;23:308–17. 10.1093/heapol/czn024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bailie R, Griffin J, Kelaher M, et al. . Sentinel sites evaluation: final report. Canberra: Report prepared by Menzies School of Health Research for the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016626supp001.pdf (419.5KB, pdf)