Abstract

Objective

To compare loneliness, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes between empty-nest and not-empty-nest older adults in rural areas of Liuyang city, Hunan, China.

Methods

A cross-sectional multi-stage random cluster survey was conducted from November 2011 to April 2012 in Liuyang, China. A total of 839 rural older residents aged 60 or above completed the survey (response rate 97.6%). In line with the definition of empty nest, 25 participants who had no children were excluded from the study, while the remaining 814 elderly adults with at least one child were included for analysis. Loneliness and depressive symptoms in rural elderly parents were assessed using the short-form UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-6) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Major depressive episodes were diagnosed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I).

Results

Significant differences were found between empty-nest and not-empty-nest older adults regarding loneliness (16.19±3.90 vs. 12.87±3.02, Cohen’s d=0.97), depressive symptoms (8.50±6.26 vs. 6.92±5.19, Cohen’s d=0.28) and the prevalence of major depressive episodes (10.1% vs. 4.6%) (all p<0.05). After controlling for demographic characteristics and physical disease, the differences in loneliness, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes remained significant. Path analysis showed that loneliness mediated the relationship between empty-nest syndrome and depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes.

Conclusion

Loneliness and depression are more severe among empty-nest than not-empty-nest rural elderly adults. Loneliness was a mediating variable between empty-nest syndrome and depression.

Keywords: loneliness, depression, empty-nest elderly

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There has been little research on the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between empty-nest syndrome and depression.

Empty-nest elderly were defined in this study as those whose children had lived away from their original township for at least 10 of the past 12 months, while previous studies only considered the location of residence of elderly parents and their adult children at the time of investigation.

This study recruited older adults (60 or above) from one county in Hunan, China, so it is not nationally representative of rural elderly adults in China.

As this is a cross-sectional study it can only indicate correlations between empty-nest syndrome and loneliness, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes.

Introduction

China became an ageing society at the end of the 20th century due to rapid economic growth, extended life expectancy and reduced fertility. The Sixth National Census in 2010 showed that 13.3% of the total population was aged 60 and above, an increase of 2.9% compared to the Fifth National Census in 2000.1 It was estimated that the proportion of people aged 60 and above will reach one third by 2050.1 Urbanisation has also dramatically increased in China. Approximately 252 million rural residents had moved to urban areas by the end of 2014, 78% of whom were aged between 15 and 59,2 leaving behind a huge number of older adults in the countryside. In China, the elderly are traditionally cared for by their family members, mainly spouses and adult children. The disintegration of the extended family in recent years has meant that often no grown-up children are available to help older adults when required. A previous study in non-immigrant elderly Indian subjects indicated that although they could get help from others and live independently, the departure of their adult children caused deep loneliness in parents.3

The mental health of the rural elderly, especially empty-nesters, is of serious concern in China.4–7 A number of studies in this population have focused on different aspects of mental health, mainly loneliness and depressive symptoms. Loneliness is a negative affective state, experienced when a person perceives themselves as socially isolated or has little and/or poor social interaction.8–10 A cross-sectional study in Anhui province showed that 78.1% of the older population experienced moderate to severe loneliness (n=5652).11 In a population-based survey in Hubei province, the authors reported that 54.5% of empty-nesters experienced moderate or high levels loneliness, which was higher than the 44.4% found in the non-empty-nest group (n=590).12 A comparative study in rural Hubei province reported that loneliness and depressive symptoms were more prevalent in the empty-nest elderly than in the not-empty-nest elderly (35.93±9.37 vs. 34.08±9.30, p=0.017; 8.81±6.50 vs. 7.66±6.09, p=0.028, respectively).13 Depressive symptoms are also common in the empty-nest elderly. A meta-analysis showed that depression affects 40.4% of the empty-nest rural elderly in China (95% CI 28.6% to 52.2%).12 The authors of a study in conducted in Yongzhou city reported that the prevalence of depression (mild depression or above) among the empty-nest elderly was higher than that among the non-empty-nest elderly (79.7% vs. 67.9%, p=0.003).14 These studies consistently reported that empty-nest syndrome was correlated with worse mental health outcomes.

However, there are methodological limitations to these studies. The definitions of empty-nest elderly varied in the different studies. For example, the empty-nest elderly were defined as those who had children but did not live with any of them,4 as those who did not live with their children or did not have any children,15 and as those without children or whose children who had left home, and so who lived alone or with a spouse.16 These definitions only considered the living situations of elderly parents and adult children at the time of investigation. However, in real life, adult children may travel back and forth between urban and rural areas. For example, most migrant workers travel back to their homes in the countryside and live there for several weeks during the Chinese New Year or other festivals. Also, some children who do not live with their parents may have homes nearby (eg, in the same village) and so be able to visit and take care of their parents. In this study, empty-nest elderly were defined as those who had at least one adult child and all of whose children had lived away from their original township for at least 10 of the past 12 months prior to interview.

The purpose of this study was to compare loneliness, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes between empty-nest and non-empty-nest older adults in Liuyang city, Hunan province, China using a community-based survey. We hypothesise that empty-nest rural elderly aged 60 and above are more susceptible to loneliness, major depressive episodes and depressive symptoms compared with not-empty-nest elderly. Furthermore, given that loneliness had been shown to be a predictor of depressive symptoms,17 18 we hypothesise that loneliness is the mediating factor in the relationship between empty-nest syndrome and depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes.

Methods

Samples and sampling

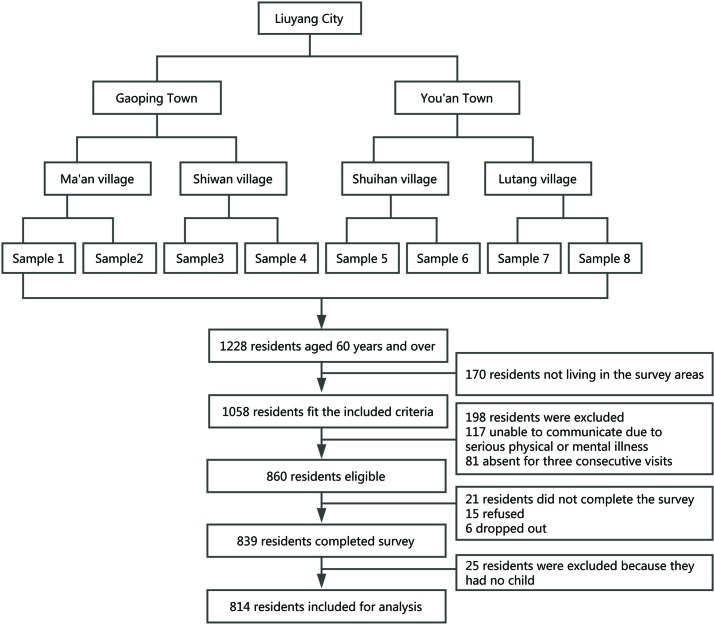

A multi-stage randomised cluster sampling method was used (figure 1). Two out of 33 townships in Liuyang, Hunan, China, were randomly selected, two villages were randomly selected from each township, and then two village teams (the smallest rural community in China) were randomly selected from each village. A total of eight village teams were finally included.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participant enrolment.

The sample only included adults aged 60 and above who lived in rural Liuyang. The inclusion criteria were: (1) age ≥60, (2) living at the survey site for at least 6 months, (3) being at home during the investigation period, and (4) able to participate in the study. Of the 1058 elderly living in the selected areas, 860 met the inclusion criteria, 839 of whom returned questionnaires for a response rate of 97.6%. Living with others besides one’s children, cognitive impairment or length of separation from one’s children were not exclusion criteria. Twenty-five of the 839 participants were excluded because they had no children, leaving 814 elderly adults with at least one child for analysis.

Instruments and measures

General information questionnaire

We used a self-designed questionnaire to collect demographic data including age, gender, marital status, educational level, annual income per household, physical disease, number of children and residence status. Information about where each child of the participant lived and how long they had lived there in the last 12 months before the interview was also collected.

Based on the location of residence of their adult children, the 814 elderly parents were divided into two groups: an empty-nest and a not-empty-nest group. Empty-nest elderly were those whose children had all lived away from their original township for at least 10 of the past 12 months before the interview. For the not-empty-nest group, at least one adult child had lived nearby for more than 2 of the past 12 months.

University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale Short-form (ULS-6)

The University of Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale Short-form (ULS-8) was developed to determine the perception and degree of loneliness. It consists of eight questions which are scored from 1 to 4.9 During the translation and validation of the Chinese version of the ULS-8, two items were deleted. Therefore the total ULS-6 score ranged from 6 to 24, with a higher score indicating greater loneliness. This instrument showed satisfactory reliability and validity in a previous study in China.19

The Geriatric Depression Scale

We used the 30-item Chinese revision of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) to assess level of depression.20 This instrument is frequently used to screen for depression in the elderly and has a retest reliability of 0.85 and a convergent validity of 0.82. Ten of the 30 items were reverse scored (a negative answer indicating depression). Subjects were asked to describe their feelings in the previous 2 weeks. Each item could be answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and was given one point if the answer indicated depression. Scores ranged from 0 to 30 with higher scores indicating a higher level of depression. GDS scores of 0–10, 11–20 and 21–30 are considered to indicate no, minimal to mild, and moderate to severe depression, respectively.21

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP)

The Chinese version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) was used to screen and diagnose major depressive episodes. A major depressive episode is defined as the presence of five or more of nine symptoms for at least 2 weeks in the month before interview, with at least one of the two core symptoms present (ie, a person with a major depressive episode must consistently have either depressed mood or loss of interest/pleasure in daily activities).

Physical disease

Participants were asked to report their physical diseases. Diagnoses of chronic illnesses made by physicians were recorded. Medical records were reviewed when necessary with consent. Those with at least one diagnosis of chronic illness were classified as ‘having a physical disease’.

Procedures and quality control

Twelve interviewers (10 medical postgraduates and two medical undergraduates) were recruited and divided into two groups which received standardised training for 1 week. After training, pilot studies were conducted at the two sites. To improve the response rates, we selected as guides some local residents who were well thought of in their communities, understood and supported our research, and were good communicators.

Face-to-face interviews to collect information were held from 23 November 2011 to 20 April 2012. Most interviews were conducted in private in participants’ homes. Before the interview, the participant was informed about the background and purpose of our research and signed an informed consent form detailing their rights. This study was approved by Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China. Two experienced investigators, one from each group of interviewers, were responsible for quality control which consisted of observing and monitoring the quality of interviews, collecting all completed questionnaires daily, checking for errors and missing items, and determining whether the respondent should be interviewed again to obtain missing answers and to correct errors. During the survey, we randomly selected 45 cases for re-interview 1–2 weeks after the initial interview, which was conducted by a single investigator blind to the results of the first interview. The test-retest correlation coefficients of ULS-6 and GDS were 0.722 and 0.702, respectively.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS/IBM, Chicago, IL). The demographic characteristics of the 814 rural elderly participants were compared using the χ2 test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The ULS-6 and GDS scores of rural empty-nesters were compared with those of rural not-empty-nesters using Student’s t-test. Associations between living situation, loneliness and depressive symptoms among the rural elderly were examined using multiple linear regressions controlling for age, gender, marital status, income, educational level and physical disease. Risk factors for major depressive episodes were explored using binary logistic regression. The significance level was set at p<0.05. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were 0.05 and 0.10, respectively.

To examine the hypothesis that loneliness mediates the relationship between empty-nest syndrome and depression, path analysis was conducted using AMOS 17.0. Living situation (empty nest syndrome or not), loneliness, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes were included in the models. The minimum fit function χ2 value (CMIN), CMIN/DF, comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with 90% confidence intervals were used to estimate the model fit.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Of the 814 rural elderly (426 men and 388 women), 436 (53.6%) were part of a couple, 335 (41.2%) were empty-nest elderly and 479 (58.8%) were not-empty-nest elderly. The participants ranged in age from 60 to 90 years (mean 69.1±7.1) and had 0–15 years (mean 3.5±2.8) of formal education. The demographic characteristics of the empty-nest and not-empty-nest groups are compared in table 1. No significant differences between the groups were found regarding age, gender, marital status, educational level, annual income per household or physical disease (all p>0.05).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics between not-empty-nest and empty-nest older adults

| Variable | Not-empty-nest (n=479) |

Empty-nest (n=335) |

Total (n=814) |

χ2/Z | p Value | |||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 60–65 | 171 | 35.7 | 134 | 40.0 | 305 | 37.5 | 3.469 | 0.483 |

| 66–70 | 113 | 23.6 | 80 | 23.9 | 193 | 23.6 | ||

| 71–75 | 103 | 21.5 | 61 | 18.1 | 164 | 20.1 | ||

| 76–80 | 59 | 12.3 | 33 | 9.9 | 92 | 11.4 | ||

| 81– | 33 | 6.9 | 27 | 8.1 | 60 | 7.4 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 251 | 52.4 | 175 | 52.2 | 426 | 52.3 | 0.002 | 1.000 |

| Female | 228 | 47.6 | 160 | 47.8 | 388 | 47.7 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 370 | 77.2 | 239 | 71.3 | 609 | 74.8 | 3.643 | 0.059 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed/never married | 109 | 22.8 | 96 | 28.7 | 205 | 25.2 | ||

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Below primary school | 127 | 26.5 | 88 | 26.3 | 215 | 26.4 | 0.254 | 0.881 |

| Primary school | 291 | 60.8 | 208 | 62.1 | 499 | 61.3 | ||

| Middle school or above | 61 | 12.7 | 39 | 11.6 | 100 | 12.3 | ||

| Annual income per household (RMB) | ||||||||

| <1800 | 183 | 38.2 | 132 | 39.4 | 315 | 38.7 | 0.145 | 0.930 |

| 1800–5000 | 186 | 38.8 | 129 | 38.5 | 315 | 38.7 | ||

| >5000 | 110 | 23.0 | 74 | 22.1 | 184 | 22.6 | ||

| Physical disease | ||||||||

| Yes | 280 | 58.5 | 197 | 58.8 | 477 | 58.6 | 0.010 | 0.942 |

| No | 199 | 41.5 | 138 | 41.2 | 337 | 41.4 | ||

Between-group comparison of loneliness, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes

Between-group comparisons of ULS-6 score, GDS score and major depressive episodes are shown in table 2. The mean scores for loneliness and depressive symptoms, and the prevalence of major depressive episodes are significantly higher in the empty-nest group (all p<0.05). The effect size of empty-nest syndrome on loneliness was highly significant, while the effect size of empty-nest syndrome on depressive symptoms was slightly significant (Cohen’s d=0.97 and 0.28, respectively).

Table 2.

Comparison of ULS-6 scores, GDS scores and prevalence of major depressive episodes between not-empty-nest and empty-nest older adults

| Variable | Not-empty-nest (n=479) | Empty-nest (n=335) | χ2/t | Cohen’s d | p Value |

| ULS-6 score (mean±SD) | 12.87±3.02 | 16.19±3.90 | 13.08 | 0.97 | 0.000 |

| GDS score (mean±SD) | 6.92±5.19 | 8.50±6.26 | 3.80 | 0.28 | 0.000 |

| Major depressive episode (N, %) | 22 (4.6) | 34 (10.1) | 9.500 | – | 0.003 |

GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; ULS-6, UCLA-Loneliness Scale.

Cohen’s d effect size: low significance (0.2–0.5), moderate significance (0.5–0.8), high significance (>0.8).

Multivariate analysis

The results of multiple linear regression of ULS-6 scores and GDS scores are shown in table 3. The independent variables were gender, age, marital status, annual income per household, educational level, physical disease and living situation (empty-nest or not-empty-nest). The empty-nest elderly who had unstable marital status and physical diseases had significantly higher ULS-6 scores. The empty-nest elderly who had lower educational levels and income, unstable marital status and had physical diseases had significantly higher GDS scores.

Table 3.

Correlates of loneliness and depressive symptoms among 814 rural older adults in Liuyang, China

| Independent variable | Loneliness | Depressive symptoms | ||||||

| Coefficient | Std. coefficient | t | p Value | Coefficient | Std. coefficient | t | p Value | |

| Gender | −0.377 | −0.050 | −1.506 | 0.133 | −0.368 | −0.032 | −0.914 | 0.361 |

| Age | 0.029 | 0.055 | 1.613 | 0.107 | 0.039 | 0.049 | 1.352 | 0.177 |

| Marital status | 1.275 | 0.147 | 4.382 | 0.000 | 1.200 | 0.091 | 2.566 | 0.010 |

| Annual income per household | 1.433E-5 | 0.026 | 0.828 | 0.408 | −9.623E-5 | −0.117 | −3.460 | 0.001 |

| Educational level | −0.404 | −0.065 | −1.869 | 0.062 | −0.959 | −0.102 | −2.761 | 0.006 |

| Physical disease | −0.749 | −0.098 | −3.142 | 0.002 | −2.946 | −0.254 | −7.682 | 0.000 |

| Living situation (empty-nest or not-empty-nest) |

3.245 | 0.423 | 13.673 | 0.000 | 1.465 | 0.126 | 3.839 | 0.000 |

Using the same set of independent variables, a logistic regression model was used to compare the prevalence of major depressive episodes between empty-nest and not-empty-nest elderly (table 4). Empty-nest syndrome was correlated with a higher prevalence of major depressive episodes (OR 2.41, 95% CI 1.34 to 4.34). Lower income and physical diseases were also risk factors for major depressive episodes.

Table 4.

Correlates of major depressive episodes among 814 rural older adults in Liuyang, China

| Variable | N | MDE | |

| OR (95% CI) | |||

| Gender | Male | 426 | Ref |

| Female | 388 | 0.56 (0.30 to 1.04) | |

| Age | 60–65 | 305 | Ref |

| 66–70 | 193 | 1.16 (0.50 to 2.69) | |

| 71–75 | 164 | 1.48 (0.65 to 3.37) | |

| 75–80 | 92 | 1.84 (0.70 to 4.86) | |

| 80- | 60 | 1.61 (0.54 to 4.85) | |

| Marital status | Married | 610 | Ref |

| Divorced/separated/ widowed/never married | 204 | 1.26 (0.67 to 2.39) | |

| Educational level | Middle school | 215 | Ref |

| Primary school | 499 | 4.39 (0.90 to 21.37) | |

| Below primary school | 100 | 2.64 (0.60 to 11.74) | |

| Annual income per household (RMB) | >5000 | 315 | Ref |

| 1800–5000 | 315 | 7.54 (1.74 to 32.62) | |

| <1800 | 184 | 6.01 (1.38 to 26.26) | |

| Physical disease | No | 280 | Ref |

| Yes | 199 | 8.67 (3.34 to 22.47) | |

| Living situation | Not-empty-nest | 335 | Ref |

| Empty-nest | 479 | 2.41 (1.34 to 4.34) | |

MDE, major depressive episode.

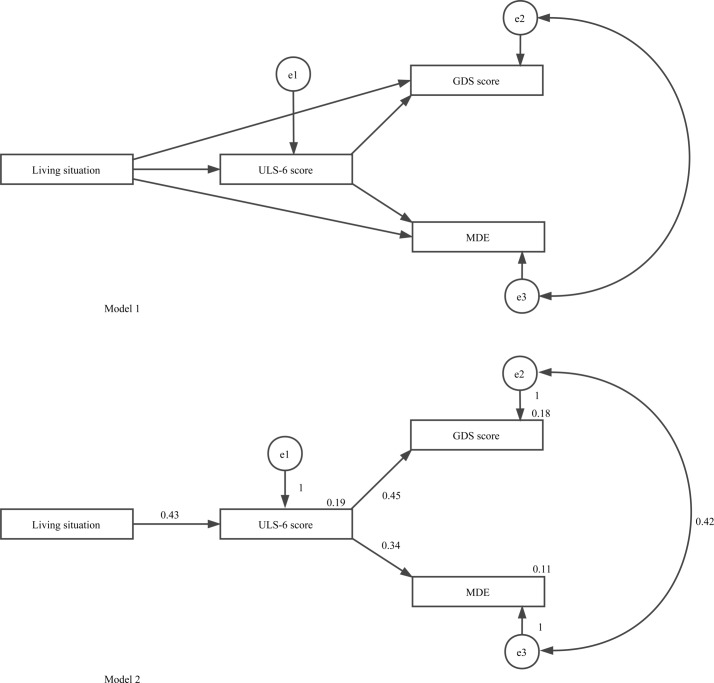

Path analysis

Based on the results of the regressive model, we established two path analysis models to explore the relationship between living situation, loneliness, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes (figure 2). There are six hypotheses in model 1. The fit indices were not satisfying for this model (CMIN=0, IFI=1, CFI=1, RMSEA=0.343).

Figure 2.

A path diagram showing the observed direct effects between variables using path analysis. Model 1: Hypothesised model of living situation, loneliness, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes (MDE). Model 2: Final model of living situation, loneliness, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes.

We then removed the path between living situation and depressive symptoms and the path between living situation and major depressive episodes, and created model 2. There are four hypotheses in model 2: (i) that living situation had a direct effect on loneliness (0.43); (ii) that loneliness had a direct effect on depressive symptoms (0.42); and (iii) that loneliness had a direct effect on major depressive episodes (0.32). Loneliness played a mediating role between living situation, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes. The fit indices were satisfying for this model (CMIN=2.896, CMIN/DF=1.448, p=0.235, IFI=0.998, CFI=0.998, RMSEA=0.023).

Discussion

We found that after controlling for demographic characteristics and physical disease, empty-nest older adults had significantly higher levels of loneliness and depressive symptoms, and a higher prevalence of major depressive episodes. Moreover, the relationship between empty-nest syndrome and depression was mediated by loneliness. These results support our hypothesis that the departure of their adult children may have a negative impact on the mental health of rural elderly parents.

Empty-nest syndrome was associated with increased loneliness in the rural elderly (Cohen’s d=0.97). After controlling for demographic variables and physical disease, the difference remained statistically significant. This is consistent with a previous study reporting a higher rate of loneliness in the empty-nest elderly.4 Other risk factors for loneliness include single status and physical disease. Loneliness is a subjective feeling related to having few and/or poor interpersonal relationships. Our results indicate that spouses and adult children are important sources of social support for the rural elderly. Physical disease may cause loneliness by limiting the ability of the rural elderly to participate in social activities.

The GDS scores of empty-nest elderly were higher than those of not-empty-nest elderly (Cohen’s d=0.28). This result is consistent with a previous study reporting a mean GDS score among the rural elderly of 8.73.22 The prevalence of major depressive episodes is also significantly higher in empty-nest than in not-empty-nest older adults (10.1% vs. 4.6%, p<0.05), and both are higher than in subjects aged 15 and over in four provinces in China (3.2%).23 Therefore, empty-nest rural elderly are more likely to experience both depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes. Other risk factors for depressive symptoms include single status, lower educational level, lower income and physical disease, while only lower income and physical disease are correlated with major depressive episodes. These results are consistent with previous studies which found that lower socio-economic status and physical disease are risk factors for depression.24

The path analysis shows that empty-nest syndrome does not have a significant direct effect on depression among the rural elderly, but that loneliness is the mediating factor between empty-nest syndrome and depression. Our findings may have important implications. Depression in the rural elderly, particularly those whose adult children have left them, might be prevented or mitigated if loneliness were reduced. Potential measures include facilitating video and/or audio communication between the empty-nest rural elderly and their adult children living in urban areas,25 encouraging or organising local group activities to promote social integration and increase social support among rural older adults,26; and providing peer support by identifying younger and capable older adults who are willing to help other elderly people.27 Loneliness is not only related to adverse mental health outcomes, but also to a variety of medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, dementia and all-cause mortality.28–32 Therefore, it is important to develop and validate interventions targeting social connections for the elderly in rural China, as well as in other countries.

The strength of this study is that we focused on a rapidly growing vulnerable population—the rural elderly. However, several limitations need to be considered when interpreting our results. First, the sample in this study consists of older adults (60 or above) living in one county in Hunan, China. It is not a nationally representative sample of the rural elderly in China and does not provide information on older urban adults. Empty-nest syndrome may differ in different parts of China. Rural residents in more developed rural communities, such as in the east and/or coastal areas, are probably less likely to become migrant workers, and so older adults in these areas are less likely to be empty-nesters. Second, we did not examine some variables that may be relevant to the observed relationship between empty-nest syndrome and loneliness and depression, such as the quality of the parent–child relationship, and the frequency and quality of contact during their separation. Social support resources other than spouses and children (for instance, other family members and friends) were not considered. These should be investigated in future research. Third, this is a cross-sectional study. Our results only indicate the correlations between empty-nest syndrome and loneliness, depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes. Further intervention studies aimed at preventing or treating depression in this population through providing social connections and promoting social integration are warranted.

Ethics and consent to participate statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the School of Public Health of Central South University. Each participant provided written informed consent before participating in the study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank village cadres for guiding us to visit each household in the rural regions of Liuyang county, Hunan province, China.

Footnotes

Contributors: LZ and SYX conceived and designed the study. GJW, MH and SYX collected the data. GJW and LZ analyzed and interpreted the data. GJW drafted the article, while LZ, MH and SYX critically revised it for intellectual consent. All authors gave final approval to the version submitted for publication.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Support Program (MZ, no. 2009BAI77B03 and SYX, no. 2009BAI77B01) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University, China (GJW, 2015zzts104).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Review Committee of the Xiangya School of Public Health of Central South University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We have no unpublished data to share.

References

- 1. National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. The main data bulletin of the sixth national population census (no. 1). 2011. http://www.stats.gov.cn/ztjc/zdtjgz/zgrkpc/dlcrkpc/dlcrkpczl/201104/t20110428_70008.htm (accessed 30 Apr 2016).

- 2. PRC, National Health and Family Planning Commission. 2015. Report on China’s migrant population development-2015. China: China Population Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miltiades HB. The social and psychological effect of an adult child’s emigration on non-immigrant Asian Indian elderly parents. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2002;17:33–55. 10.1023/A:1014868118739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu LJ, Guo Q. Loneliness and health-related quality of life for the empty nest elderly in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Qual Life Res 2007;16:1275–80. 10.1007/s11136-007-9250-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bocker E, Glasser M, Nielsen K, et al. . Rural older adults' mental health: status and challenges in care delivery. Rural Remote Health 2012;12:2199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. He G, Xie JF, Zhou JD, et al. . Depression in left-behind elderly in rural China: prevalence and associated factors. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2016;16:638–43. 10.1111/ggi.12518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lutfiyya MN, Bianco JA, Quinlan SK, et al. . Mental health and mental health care in rural America: the hope of redesigned primary care. Dis Mon 2012;58:629–38. 10.1016/j.disamonth.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dyal SR, Valente TW. A systematic review of loneliness and smoking: small effects, big implications. Subst Use Misuse 2015;50:1697–716. 10.3109/10826084.2015.1027933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hays RD, DiMatteo MR. A short-form measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess 1987;51:69–81. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laursen B, Hartl AC. Understanding loneliness during adolescence: developmental changes that increase the risk of perceived social isolation. J Adolesc 2013;36:1261–8. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang G, Zhang X, Wang K, et al. . Loneliness among the rural older people in Anhui, China: prevalence and associated factors. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26:1162–8. 10.1002/gps.2656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xin F, Liu XF, Yang G, et al. . Prevalence of depression in Chinese empty-nest elderly: a meta-analysis. Chinese Journal of Health Statistics 2014;31:278–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu LJ, Guo Q. Life satisfaction in a sample of empty-nest elderly: a survey in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Qual Life Res 2008;17:823–30. 10.1007/s11136-008-9370-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xie LQ, Zhang JP, Peng F, et al. . Prevalence and related influencing factors of depressive symptoms for empty-nest elderly living in the rural area of YongZhou, China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2010;50:24–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liang Y, Wu W. Exploratory analysis of health-related quality of life among the empty-nest elderly in rural China: an empirical study in three economically developed cities in eastern China. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014;12:59 10.1186/1477-7525-12-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang Z, Shu D, Dong B, et al. . Anxiety disorders and its risk factors among the Sichuan empty-nest older adults: a cross-sectional study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013;56:298–302. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 2010;40:218–27. 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging 2010;25:453–63. 10.1037/a0017216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou L, Li Z, Hu M, et al. . [Reliability and validity of ULS-8 loneliness scale in elderly samples in a rural community]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2012;37:1124–8. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2012.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. . Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982;17:37–49. 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Su D, Wu XN, Zhang YX, et al. . Depression and social support between China' rural and urban empty-nest elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012;55:564–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin YY, Cao GH, Zhao J. Characteristics of depression, loneliness, social support of elderly in Shandong province. Chinese Journal of Gerontology 2015;22:7200–2. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gui LH, Xiao SY. Prevalence and related factors of suicidal ideation and attempts in patients with major depressive episode in rural community of Liuyang City. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;23:651–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu Y, Yang J, Gao J, et al. . Decomposing socioeconomic inequalities in depressive symptoms among the elderly in China. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1214 10.1186/s12889-016-3876-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chopik WJ. The benefits of social technology use among older adults are mediated by reduced loneliness. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2016;19:551–6. 10.1089/cyber.2016.0151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen Y, Hicks A, While AE. Loneliness and social support of older people living alone in a county of Shanghai, China. Health Soc Care Community 2014;22:429–38. 10.1111/hsc.12099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hacihasanoğlu R, Yildirim A, Karakurt P. Loneliness in elderly individuals, level of dependence in activities of daily living (ADL) and influential factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012;54:61–6. 10.1016/j.archger.2011.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holwerda TJ, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, et al. . Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:135–42. 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou Z, Wang P, Fang Y. Loneliness and the risk of dementia among older Chinese adults: gender differences. Aging Ment Health 2017:1–7. 10.1080/13607863.2016.1277976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Christiansen J, Larsen FB, Lasgaard M. Do stress, health behavior, and sleep mediate the association between loneliness and adverse health conditions among older people? Soc Sci Med 2016;152:80–6. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD. Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med 2009;71:836–42. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b40efc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tilvis RS, Laitala V, Routasalo PE, et al. . Suffering from loneliness indicates significant mortality risk of older people. J Aging Res 2011;2011:1–5. 10.4061/2011/534781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.