Abstract

Introduction

Patients with in-transit melanoma metastases present a therapeutic challenge. Complete surgical excision of localised disease is considered as the gold standard; however, surgery is not always acceptable and alternatives are required. Treatment results reported using imiquimod and diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) suggest that topical immunotherapies can be used to successfully treat select patients with melanoma metastases. A phase II, randomised, single centre, pilot study was designed to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of DPCP and imiquimod for the treatment of superficial, cutaneous in-transit melanoma metastases.

Methods and analysis

This is an open-label, non-superiority, pilot study with no treatment cross-over. Eligible patients are randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive topical therapy for up to 12 months with a minimum follow-up period of 12 months. The target sample size is 30 patients, with 15 allocated to each treatment arm. The primary endpoint is the number of patients experiencing a complete response of treated lesions as determined clinically using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours. This trial incorporates health-related quality of life measures and biological tissue collection for further experimental substudies. The study will also facilitate a health economic analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

Approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the participating centre, and recruitment has commenced. The results of this study will be submitted for formal publication within a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

Prospectively registered on 16 October 2015 with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12615001088538). This study conforms to WHO Trial Registration Data Set.

Keywords: In-transit, melanoma, metastases, topical, immunotherapy, clinical trial

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a proof-of-concept, pilot study with a small sample size and non-blinded design. While expediting the availability of high-quality data useful for conducting a larger trial, these factors will also reduce the generalisability of clinical findings to the in-transit melanoma patient population.

This is a complex patient group and the inclusion of patients who have failed or are unsuitable for other treatments may introduce a selection bias for those with more aggressive disease types.

The prospective design, randomised allocation of participants and strict clinical trial environment will improve the quality of data collected and evidence available for these therapies.

The provision for titrating the dose and frequency of the investigational agents will help establish an evidence-based treatment regimen. The use of standardised clinical outcome measures will produce more accurate and precise efficacy data than is currently available. This will enhance the reliability of power calculations required for a comparative superiority study.

In addition to technical information, the pilot study design will assist with evaluating the financial and logistical feasibility of establishing a full-scale study.

Introduction

There has been a sustained increase in the incidence of cutaneous melanoma worldwide, with an estimated lifetime risk now of up to 1 in 147 in the UK and 1 in 25 in other Commonwealth nations.1–3 With early detection the 5-year survival rate for melanoma is excellent (>90%), however, the prognosis remains poor in patients with recurrent, locoregional disease.4 In-transit melanoma is an advanced form of disease (≥stage IIIB) associated with a poor prognosis and significantly lower quality of life outcomes secondary to disease-related functional impairment and treatment side effects.4–6 Patients have an unpredictable clinical course and variable treatment responses.7 8 Currently, the management of these patients is varied with no consensus on the optimal therapeutic approach.

Complete surgical excision is effective for localised disease, however, surgery is often inappropriate. Locoregional treatments may improve quality of life but do not improve melanoma-specific survival. Existing strategies aim to maximise locoregional disease control while reducing disease and treatment-related morbidity. Due to the need for less-invasive, non-surgical modalities, immunological-based therapies have been investigated for the treatment of melanoma metastases.9

Topical immunotherapies may improve disease control without a significant increase in treatment-related adverse events. In certain patients diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) and imiquimod have been reported to produce response rates of up to 84% and 100%, respectively.10 11 Lesion morphology may also be an important predictor of treatment response, with higher response rates observed with superficial (epidermotropic) lesions versus nodular or bulky types.12 13 Therefore it appears patients can be rationally selected for treatment based on disease phenotype, while respecting their co-morbidities and functional status.14 The agents appear to be convenient to administer, relatively cheap and generally well-tolerated, although these findings have not been established within a formal trial setting.

Study rationale

Both agents have been reported in small case series with retrospective study designs. A phase II, randomised, proof-of-concept, pilot study was, therefore, designed to formally evaluate imiquimod and DPCP for the selective management of superficial, cutaneous in-transit melanoma metastases (PICO format below). The aim of this study is to determine if either treatment is a clinically efficacious and well-tolerated alternative to current therapies in patients who cannot undergo, refuse or have failed surgery. The trial will also formally measure patient-rated outcomes, facilitate a health economic evaluation and include biological tissue collection for further experimental substudies.

TIDAL Melanoma Study (PICO format).

Research question: Can topical imiquimod or diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) be used to effectively treat patients with superficial, cutaneous in-transit melanoma metastases?

Population: Adults ≥18 years with stage III/IV melanoma and biopsy confirmed superficial, cutaneous in-transit metastases that have failed, decline or are unsuitable for surgery.

Intervention: Patients are randomised to receive either topical imiquimod or DPCP therapy.

Comparison: This is a non-superiority, proof-of-concept, pilot study. It is not powered to detect a significant difference in the primary outcome between the investigational agents. Reference will be made to the standard of care represented by isolated limb infusion where appropriate.

Outcome: The primary endpoint is the number of patients experiencing a complete response of treated lesions within 12 months of starting treatment as determined clinically using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. Secondary outcomes include: the proportion of patients experiencing a non-complete response at 12, 18 and 24 months (partial response, stable disease or progressive disease), progression and disease-free survival, time to locoregional disease and overall disease progression, rate of treatment-related adverse events and patient-rated outcomes.

Time: The primary outcome is measured at the time of best response, with up to 12 months of treatment. Clinical assessments are performed regularly during outpatient reviews with radiological surveillance at 12, 18 and 24 months. The planned minimum follow-up duration is 12 months from the time of best response. Patients are excluded from the trial if they develop progressive locoregional disease or systemic disease and treated in accordance with the standard of care available.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

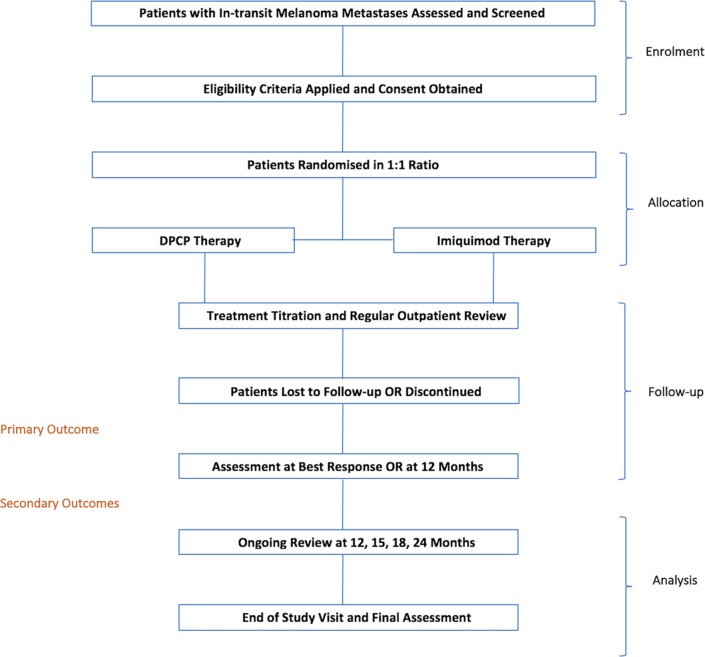

This is a phase II, randomised, proof-of-concept, pilot study to be performed at a single centre in Brisbane, Australia. It is designed as an open-label, dual arm, non-superiority trial without treatment cross-over. Eligible patients are randomised in a ratio of 1:1 to receive either topical imiquimod (treatment arm A) or DPCP (treatment arm B) therapy over a maximum of 12 months or until the time of complete response or disease progression. Treatment is performed by the patient at home allowing for intermittent scheduled clinical review within an outpatient setting. The planned minimum follow-up duration is 12 months from the best response or disease progression, and this will allow for close clinical and radiological surveillance (figure 1).

Figure 1.

TIDAL Melanoma Study flow chart. DPCP, diphenylcyclopropenone.

Pilot study rationale

Based on the existing rate of new patients treated at our institution plus the estimated accrual rate projected for the trial period, 30 subjects are planned for enrolment within the pilot study. Given this is a non-superiority, proof-of-concept, pilot study, formal power calculations were not applied to determine allocation numbers. It is expected that this target sample size will provide sufficient high-quality data to confirm the efficacy rates reported in the literature and improve the accuracy of power calculations required for a full-scale superiority study. This will also help investigators establish a standardised treatment regimen that allows for dosing adjustment with titration to effect. In addition to technical information, the pilot study will assist with evaluating the financial and logistical feasibility (including patient compliance, data collection and costs) of establishing a full-scale study. The revised procedures are intended for use within a larger programme at multiple centres as a phase II/III trial.

Allocation

Randomisation is provided by a web-based permuted block system and performed by the trial coordinator or principal investigator. The method uses permuted blocks of variable size between two and four participants. Patients are randomised in a 1:1 ratio and allocated to either treatment arm, thereby receiving one of two possible treatments.

Participants

Adults ≥18 years, with American Joint Committee on Cancer stage III or IV disease and biopsy-confirmed cutaneous in-transit melanoma metastases will be enrolled for treatment. Patients must be willing and able to comply with study requirements and provide valid consent. A minimum of five measurable lesions in anatomical locations suitable for topical treatment are required to enable initial and repeat lesion biopsies and the objective assessment of tumour response. Treated lesions will be between 2 and 15 mm in diameter that can be accurately assessed by ruler/calliper. Macular, papular or small nodular morphology types will be included. Patients must be considered unsuitable for surgery by the treating clinician due to the anatomical location, prohibitive disease factors, patient refusal or previous treatment failure. A minimum duration of 12 weeks is required between completing other biological treatments (such as isolated limb infusion (ILI) or PV-10 intralesional therapy). Women of childbearing potential must have a confirmed negative blood pregnancy test at study entry and use approved contraception throughout the study. Patients must have adequate renal, haematopoietic and hepatic function, with no clinically significant impairment. The exclusion criteria are listed below.

Exclusion Criteria.

Considered eligible for concurrent treatment with systemic therapies.

Subjects who have received chemotherapy or other systemic cancer therapy within 12 weeks of the study.

Subjects who have received other local therapy (eg, surgery, cryotherapy, laser or radiofrequency ablation) to the treatment area within 4 weeks of study treatment.

Life expectancy of less than 6 months or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≥3.

Medical or psychiatric condition that compromises the patient’s ability to complete the treatment regimen or follow-up assessments as per protocol.

Female subjects that are pregnant or lactating.

Known history of immunodeficiency, including HIV-positive subjects, uncontrolled central nervous system metastases, concomitant systemic corticosteroid or other immunosuppressive use or previous organ transplant.

Known severe concurrent or intercurrent illness including: cardiovascular, respiratory or immunological illness, psychiatric disorders or substance dependence that would, in the opinion of the Investigator, compromise safety or compliance or interfere with interpretation of study results.

Previous severe adverse or allergic reaction to either treatment agent.

Study objectives

Primary endpoint

The number of patients experiencing a complete response of treated lesions within 12 months of starting treatment as determined clinically using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST).15

Secondary endpoints

Proportion of patients experiencing a non-complete response in target lesions (partial response, stable disease and progressive disease as per RECIST) at 12, 18 and 24 months after treatment commencement.

Locol progression-free and disease-free survival.

Proportion of patients with overall disease progression including death following treatment.

Patient-rated outcomes (health-related quality of life (HRQoL)) before, at the time of best response and 12 months from the conclusion of treatment.

Rate of treatment-related adverse events.

Estimated health-related costs.

Recruitment

Potential subjects are initially assessed and screened through the Melanoma Outpatient Clinic at the Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia. Consent, enrolment, treatment and follow-up occur through a multidisciplinary trials clinic with an emphasis on the outpatient treatment of patients with in-transit melanoma. This involves specialist care provided by dermatologists, surgeons, oncologists, trial nurses and other allied health professionals. Each eligible subject is enrolled in the study for up to 12 months of treatment with imiquimod or DPCP. The aim is for a minimum follow-up duration of 12 months (and up to 24 months) following the best response or progressive disease. The total recruitment window will be open for at least 24 months and the total study length is, therefore, estimated to be up to 36 months based on recruitment rates.

Investigational agents

Imiquimod

Patients are treated using 5% topical imiquimod applied as a mixture within an aqueous cream. This concentration remains constant for the duration of treatment. A local inflammatory response is produced with application once daily, 5 days per week, with 2 rest days. The solution is applied with a 0.5 cm margin surrounding lesions and left overnight for 8-hour duration. The total treatment area is recommended as <25 cm2. The treatment is continued so that a mild to moderate dermatitis is maintained with sequential treatments and this includes the provision to reduce the treatment frequency (table 1).

Table 1.

Imiquimod and diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) treatment regimens

| Week | Imiquimod | DPCP |

| 1–8 | 5% imiquimod applied to lesions 5 days per week with 2 rest days. | 0.005% DPCP applied once weekly. |

| 8–16 | Imiquimod applied to lesions 5 days per week (as tolerated). If a sustained, moderate treatment reaction is noted then frequency modified to every second day (3 days per week). | DPCP concentration titrated to effect (up to 5% concentration) and applied once per week to lesions. DPCP can be used up to two times per week to achieve moderate treatment reaction. |

| 16–52 | Imiquimod applied on alternate days (3 days per week) to lesions as tolerated. | DPCP applied at maintenance dose and frequency to lesions as tolerated. |

Diphenylcyclopropenone

Patients are sensitised to DPCP using a 2% solution applied to a clinically accessible contact point (eg, medial arm). Two weeks following sensitisation the definitive treatment is commenced. Treatment concentrations may range from 0.005% to 5% applied as a mixture within an aqueous cream. The optimal dose of DPCP is based on an individual’s clinical response. A contact dermatitis is produced following application. The ideal maintenance dose is gradually reached by titrating the dose from 0.005% to achieve a mild to moderate dermatitis with consecutive treatments. The solution is applied to the treatment area with a 0.5 cm margin surrounding lesions and left for 24–48 hours total duration (table 1).

Treatment interruption/temporary suspension

At the discretion of clinicians, treatment can be temporarily withheld due to the development of significant treatment-related side effects. This interruption period can continue for up to 4 weeks without the patient being excluded from the trial. In the event of a severe treatment reaction the dose and frequency can also be adjusted in accordance with the regimen.

Treatment schedule

Eligible patients commence treatment within 4 weeks of signing informed consent. Both treatments are self-administered by patients or their carer with regular clinical reviews conducted in the outpatient setting (online supplementary tables 1 and 2).

Patients randomised to treatment arm A receive topical 5% imiquimod cream. This is applied to target lesions up to five times weekly for the first 8 weeks with 2 rest days. From 8 to 16 weeks if a sustained, moderate treatment reaction is achieved the frequency is modified to every second day (3 days per week). Imiquimod is applied on alternate days from weeks 16 to 52.

Patients randomised to treatment arm B receive topical DPCP cream. Patients successfully sensitised using the 2% solution commence the treatment 2 weeks after initial contact. This involves application of 0.005% DPCP once weekly for the first 8 weeks. Regular clinical review as per the treatment schedule enables titration of up to a 5% solution applied once or two times per week to achieve the desired therapeutic effect.

bmjopen-2017-016816supp001.pdf (372.1KB, pdf)

End of trial review and continuing treatment

Following the conclusion of the trial or with progression, patients will be offered further treatment at the current standard of care. Patients will continue to be reviewed at regular clinical outpatient appointments. During the final visit, a comprehensive clinical assessment of tumour response, medical examination, radiological evaluation and serum biochemical workup will be performed. If a patient experiences a complete response, further topical treatment on the trial is ceased within 4 weeks. There is no conclusive evidence concerning the effect of continuing the therapy after this point and various regimens have been reported. Arbitrarily continuing treatment may influence the validity of the disease-free and progression-free survival calculations within this study.

Statistical analysis

All subjects who are enrolled and receive either therapy will be evaluated for the primary and secondary outcomes using an intention-to-treat analysis. Exploratory univariate and bivariate analyses will be conducted to assess for variables significantly associated with a complete response and a logistic regression model will be used to adjust for significant covariates. Progression-free, disease-free and overall-survival will be calculated using Kaplan-Meier survival estimates. Treatment failures include: no clinical response after 3 months of treatment, locoregional disease recurrence or progression of target lesions within the treatment field. Persistent disease will be evaluated clinically using dermoscopy then confirmed on histopathology.

Treatment response

Based on existing evidence, it is expected that most patients will develop a clinical response within 1–3 months of commencing treatment and experience clinical regression within 6–12 months. If no clinical response is demonstrated using the treatment regimen within 3 months, topical therapy is discontinued and the patient is recorded as a treatment failure. Documentation of target lesions is performed prior to treatment commencement using standardised data collection forms and colour photography. Up to 20 measurable metastases are identified as target lesions and recorded at baseline. The change in the longest diameter for all target lesions is used to assess the objective tumour response following treatment using RECIST. Regular radiological and serum biochemical assessments are also integrated within the study schedule.

Outcomes assessments

Treatment response will be determined through clinical and photographic assessment of lesions at baseline and at the time of best response or up to 12 months following the commencement of treatment. Efficacy will be measured using RECIST with the overall response rate and clinical benefit calculated by summation of response parameters. Treatment of emergent adverse experiences will be based on the severity grade using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE v4.03). Changes in haematology, serum biochemistry and other laboratory values will be summarised using descriptive methods. Differences will be calculated relative to the values collected at study enrolment. Progression-free and disease-free survival will be monitored by clinical assessment and CT/positron emission tomography/MRI radiology will be performed for the assessment of systemic disease at baseline and at 6, 12 and 24 months after commencing treatment. All subjects will be followed for overall survival until the close of the study. Changes in patient-rated outcomes before treatment, at 12 months and the time of best response will be assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Melanoma (FACT-M), a HRQoL instrument. An estimated difference in the health-related costs will be performed after the conclusion of study by reviewing the typical expenses incurred by a patient in each treatment arm and comparing these with ILI using a projected economic bootstrapping model.

Adverse events and safety profile

Safety will be assessed by documenting toxicity using CTCAE v4.03 and recording other serious adverse events. An acceptable safety profile is defined as 80% of patients receiving the treatment without any grade IV adverse events. An interim safety assessment will be performed within 4 weeks of the fifth patient completing imiquimod and DPCP treatment.

Quality assurance

Comprehensive data management will be conducted in accordance with Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry standards with strict operating procedures and policies. Operation meetings will be held to review trial progress, supported by a minimum of annual trial management committee meetings. Patient data will be collected using standardised case report forms and entered onto a secure database. With respect to the primary and secondary endpoints, the first five participants will be reviewed by an expert dedicated reviewer and thereafter one in every five patients will undergo select review. Personal information will be collected, maintained and shared confidentially throughout and after the study’s completion. The trial coordinator is responsible for data cleaning and entry.

Substudies

Biological

In addition to examining clinical questions, this study supports a biological research programme. The trial includes the collection of blood, saliva and tumour specimens which are stored within a Melanoma and Soft Tissue Bank (HREC-10-QPAH-153). Tumour specimens include material from pretreatment biopsies with repeated biopsies performed at 4 weeks and 9 months after treatment commencement. In addition to formalin-fixed or paraffin-embedded material, fresh tissue will be provided for sequencing, RNA/protein analysis and BRAF mutation testing.

The primary objective of the translational research programme is to create an extensive tissue bank with parallel clinical information to facilitate novel investigations, hypothesis generation and validation of existing concepts. Broad research questions include: ‘Are there genetic determinants of immunotherapeutic response in melanoma?’, ‘What are the biological differences between patients capable of producing robust treatment responses versus those with progressive disease?’, ‘Are there specific biomarkers that can be used to predict disease progression or treatment response?’ and ‘Does preliminary treatment with topical immunotherapies lead to sustained biological effects or translate into subsequent treatment or significant survival differences when commenced on systemic immunotherapies?’

HRQoL and health economic evaluation

This trial uses assessments of patient-rated outcomes and changes in response to treatment. In this study, HRQoL will be assessed using the 51 item FACT-M. This is a multidimensional, melanoma-specific, validated instrument that was developed to measure HRQoL in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Derived from five sub-scales components, aggregate scores are produced where a higher value reflects improved overall well-being.16

To date, there is limited information available from formal evaluations of HRQoL in patients with in-transit melanoma metastases and this study will generate data to compare with other melanoma cohorts.14 17–20 Currently, the relative differences between topical therapies and other locoregional treatments remains unknown. We expect that DPCP and imiquimod therapy will improve locoregional disease control compared with patients’ baseline although this may be associated with higher levels of treatment-related morbidity. Consequently, it is important to measure HRQoL to determine the effects of these agents on patient-rated outcomes and differentiate them from other available therapies.

An economic assessment will be performed on the conclusion of this study incorporating various data points. The relative effect of treatment on HRQoL, disease progression, overall survival, resource consumption and estimated treatment-related costs will serve as the primary inputs. Reference will be made to ILI as long-term institutional treatment outcomes and healthcare cost data are available. It is hypothesised that imiquimod and DPCP are both relatively cheap and convenient non-invasive therapies for patients with this disease subtype.

Discussion

Existing evidence supports the use of these agents for the topical treatment of cutaneous melanoma metastases. However, there is currently high-quality efficacy and safety data and no well-established treatment regimens. Both agents are relatively inexpensive, easy to administer and require only intermittent clinician review and these properties make topical therapies attractive alternatives to more invasive and commonly used options. Counterintuitively, there is an absence of studies measuring quality of life or health-related costs in this patient group.

Priorities of this pilot study are to:

further assess the clinical efficacy and safety profile of each investigational agent;

improve the accuracy of power calculations;

establish a treatment regimen allowing for titration to therapeutic effect;

determine how many patients can be effectively recruited for treatment;

evaluate the financial and logistical feasibility of implementing these therapies.

The additional data and revised procedures will assist further trial design and coordination within a full-scale phase II/III study. If these treatments prove effective it is expected this will lead to improved patient-rated outcomes through a reduction in local disease, fewer serious treatment-related complications and more convenient application. It will also streamline review and may lead to decreased healthcare-associated expenditure. Providing multidisciplinary care within a high-quality environment will apprise of other important aspects of this complex disease.

The TIDAL Melanoma Study is an investigator-initiated trial that incorporates novel immunotherapeutics to inform on the technical aspects of treatment as well as the efficacy and safety profiles of the investigational agents, patient-rated outcomes and health economics. It aims to address a significant question with respect to the management of this challenging disease and will provide further evidence on clinical practice and treatment standards for advanced locoregional melanoma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Queensland Melanoma Project for providing the logistical support for TIDAL Melanoma Study, which is an investigator-initiated, non-sponsored study.

Footnotes

Contributors: TR (principal investigator): Manuscript writing, trial design, coordination, data collection and patient care. SW: Trial coordination, data collection and patient care. JT (trial coordinator): Trial coordination and data management. MW: Manuscript and protocol editing, trial design and patient care. HS: Trial design and manuscript editing. HPS: Trial design and coordination. BMS—Manuscript editing, trial design, coordination and patient care.

Funding: TR was the recipient of a Junior Research Fellowship funded by the Queensland Government.

Competing interests: TR was the recipient of a Junior Research Fellowship awarded by the Queensland Government and Clinical Research Fellowship awarded by the PA Research Foundation both of which supported the establishment of this study.

Patient consent: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study has Metro South Human Research Ethics Committee approval (HREC/15/QPAH/632) and is being conducted in accordance with appropriate human research standards using the TIDAL-M-01 Protocol Version 3.5.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. MacKie RM, Hauschild A, Eggermont AM, et al. Epidemiology of invasive cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol 2009;20 Suppl 6(suppl 6):vi1–7. 10.1093/annonc/mdp252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giblin A-V, Thomas JM, Incidence, mortality and survival in cutaneous melanoma. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 2007;60:32–40. 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thompson JF, Scolyer RA, Kefford RF, et al. Cutaneous melanoma. The Lancet 2005;365:687–701. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70937-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6199–206. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cornish D, Holterhues C, van de Poll-Franse LV, et al. A systematic review of health-related quality of life in cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol 2009;20(suppl 6):vi51–58. 10.1093/annonc/mdp255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cormier JN, Ross MI, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prospective assessment of the reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Melanoma questionnaire. Cancer 2008;112:2249–57. 10.1002/cncr.23424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pawlik TM, Ross MI, Johnson MM, et al. Predictors and natural history of in-transit melanoma after sentinel lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:587–96. 10.1245/ASO.2005.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Read RL, Haydu L, Saw RP, et al. In-transit melanoma metastases: incidence, prognosis, and the role of lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:475–81. 10.1245/s10434-014-4100-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hayes AJ, Clark MA, Harries M, et al. Management of in-transit metastases from cutaneous malignant melanoma. Br J Surg 2004;91:673–82. 10.1002/bjs.4610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Florin V, Desmedt E, Vercambre-Darras S, et al. Topical treatment of cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma using combined imiquimod and 5-fluorouracil. Invest New Drugs 2012;30:1641–5. 10.1007/s10637-011-9717-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Damian DL, Saw RP, Thompson JF et al. Topical immunotherapy with diphencyprone for in transit and cutaneously metastatic melanoma. J Surg Oncol 2014;109:308–13. 10.1002/jso.23506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Read T, Webber S, Tan J, et al. Diphenylcyclopropenone for the treatment of cutaneous in-transit melanoma metastases - results of a prospective, non-randomized, single-centre study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017. Epub ahead of print 10.1111/jdv.14422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moncrieff M, Fadhil M, Garioch J et al. Topical diphencyprone for the treatment of locoregional intralymphatic melanoma metastases of the skin; the 5-year Norwich experience. Br J Dermatol 2016;174:1141–2. 10.1111/bjd.14314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yeung C, Petrella TM, Wright FC, et al. Topical immunotherapy with diphencyprone (DPCP) for in-transit and unresectable cutaneous melanoma lesions: an inaugural Canadian series. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017;13:383–8. 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1286984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cormier JN, Ross MI, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prospective assessment of the reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Melanoma questionnaire. Cancer 2008;112:2249–57. 10.1002/cncr.23424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beesley VL, Smithers BM, Khosrotehrani K, et al. Supportive care needs, anxiety, depression and quality of life amongst newly diagnosed patients with localised invasive cutaneous melanoma in Queensland, Australia. Psychooncology 2015;24:763–70. 10.1002/pon.3718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beesley VL, Smithers BM, O’Rourke P, et al. Variations in supportive care needs of patients after diagnosis of localised cutaneous melanoma: a 2-year follow-up study. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:93–102. 10.1007/s00520-016-3378-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jiang BS, Speicher PJ, Thomas S, et al. Quality of life after isolated limb infusion for in-transit melanoma of the extremity. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:1694–700. 10.1245/s10434-014-3979-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bagge AS, Ben-Shabat I, Belgrano V, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients Who have In-Transit Melanoma Metastases Treated with Isolated Limb Perfusion. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:2062–9. 10.1245/s10434-016-5103-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016816supp001.pdf (372.1KB, pdf)