Abstract

Objectives

Investigate the acceptability of financial incentives for initiating a medically supervised benzodiazepine discontinuation programme among people with long-term benzodiazepine use and to identify programme features that influence willingness to participate.

Methods

We conducted a discrete choice experiment in which we presented a variety of incentive-based programs to a sample of older adults with long-term benzodiazepine use identified using the outpatient electronic health record of a university-owned health system. We studied four programme variables: incentive amount for initiating the programme, incentive amount for successful benzodiazepine discontinuation, lottery versus certain payment and whether partial payment was given for dose reduction. Respondents reported their willingness to participate in the programmes and additional information was collected on demographics, history of use and anxiety symptoms.

Results

The overall response rate was 28.4%. Among the 126 respondents, all four programme variables influenced stated preferences. Respondents strongly preferred guaranteed cash-based incentives as opposed to a lottery, and the dollar amount of both the starting and conditional incentives had a substantial impact on choice. Willingness to participate increased with the amount of conditional incentive. Programme participation also varied by gender, duration of use and income.

Conclusions

Participation in an incentive-based benzodiazepine discontinuation programme might be relatively low, but is modifiable by programme variables including incentive amounts. These results will be helpful to inform the design of future trials of benzodiazepine discontinuation programmes. Further research is needed to assess the financial viability and potential cost-effectiveness of such economic incentives.

Keywords: benzodiazepines, addiction, older adults, financial incentives, behavioral economics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to provide evidence on the acceptability of financial incentives for benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with a history of long-term benzodiazepine use.

It provides insights into the preferences of this group of patients and will be helpful to inform the design of future trials of benzodiazepine discontinuation programmes.

Our findings are limited by the relatively small number of participants and the focus on one study site.

As we are using a stated preferences method, it is not clear whether patients would make the exact same choices when faced with the real-life decision.

Introduction

Benzodiazepines are frequently used to treat insomnia and anxiety disorders. In 2013, 8.6% of Americans age 65 or above filled one or more benzodiazepine prescription.1 While short-term use for panic disorder and insomnia are supported by some clinical practice guidelines,2–4 long-term use is associated with serious risks, including overdose,1 misuse and use disorder,5 falls,6 motor vehicle crashes,7 cognitive impairment8 and dementia,9 particularly in older adults. Despite known risks associated with long-term use, discontinuing therapy with benzodiazepines can be very difficult because of physiological dependence as well as the potential for return of the symptoms that prompted benzodiazepine initiation.5 While withdrawal symptoms can be mitigated in part by a slow taper,10 many patients are resistant to initiation of the taper.11 Strategies such as providing patient education about the risks of benzodiazepine use have proven only modestly effective in encouraging discontinuation of therapy.12

In this context, giving people monetary incentives conditional on achieving reduction in use and discontinuation might be a useful approach. Standard economic theory suggests that giving people monetary incentives conditional on achieving a specific health-related goal can make the net benefits of behavioural change positive, immediate and more tangible for some individuals, and therefore increase the likelihood of seeing the target population adopt healthier behaviours.13 While this type of strategy is increasingly used and has been shown effective in several contexts,14–19 no studies have explored the use of incentives in benzodiazepine use. Besides setting a monetary value that rewards a well-defined outcome, incentive design entails a careful consideration of a variety of features, especially in the case of behaviours involving repeated choices whose long-term consequences are likely to be underweighted in the decision-making process and can lead to persistent unhealthy habits. Characteristics of payments such as their frequency (regular versus one-off),20 certainty (guaranteed payments versus lotteries),21 or their nature (cash versus vouchers), must be considered as they can influence take-up and success. Also, individuals often exhibit decision-making biases such as loss aversion, present bias22 or the overweighting of small probabilities and previous work has shown that financial incentives designed around these biases are particularly effective in influencing behaviours.23 However, relatively little is known about the influence of incentive design on the willingness to participate in incentive-based programs and how to adapt the design to different populations/behaviours to maximise take-up, especially in the case of older adults. Previous work in this population group has shown that even small incentives are likely to increase stated uptake of a physical activity programme and that cash incentives were preferred over vouchers.24 A recent UK study on acceptability of financial incentives targeted a range of behaviours showed that lottery-based incentives were not deemed acceptable and that older people preferred programmes with no incentives.25 Identifying effective incentives becomes even more challenging when considering compulsive and potentially harmful behaviours that may be perceived as acceptable and safe such as the use of physician-prescribed drugs in general and benzodiazepine use in particular. Thus, there is a clear gap in knowledge about optimal incentive structure to present to older individuals to induce programme participation for healthy behavioural change. This study presents a unique opportunity to narrow this gap by focusing on patients with long-term prescription benzodiazepine use.

In this study, we used a discrete choice experiment (DCE) to investigate the acceptability of financial incentives for initiating a medically supervised benzodiazepine discontinuation programme among long-term benzodiazepine users and to identify programme features that influence the willingness to participate. More specifically, we randomly presented a variety of incentive-based programs that differed according to a set of key features (eg, incentive amount, lottery versus certain payment) to a sample of older adults (age 50+ years) with long-term benzodiazepine use. We then asked respondents to report their willingness to participate in the programmes and collected additional information on demographics, history of use and anxiety symptoms. We used discrete choice modelling to investigate the trade-offs that individuals make between programme features as well as patient factors that affect willingness to participate.

Methods

Data collection

We identified potential subjects from the patient population of the primary care and behavioural health outpatient practices of a university-owned health system. Eligible participants were aged 50 or older, with an anxiety diagnosis at any point as an outpatient or with anxiety listed on their active problem list within the electronic health record. Additionally, eligible participants must have had at least three benzodiazepine prescription orders in the previous 12 months, with the most recent prescription within 90 days of our initial screening for study participants. Those with a history of a seizure disorder were excluded. Before contacting any participants, we reached out to each provider to give them the opportunity to opt-out any of their patients who they did not wish to participate in the study.

We contacted the remaining eligible participants over phone from May 2015 to August 2015. Contacted individuals who were no longer taking their benzodiazepine medication(s) were excluded as ineligible. Research staff obtained verbal consent over phone and subsequently randomised each participant to either version A or B of the study questionnaire (see Design of the choice experiment section). Stamped and addressed envelopes were provided with the questionnaires for participants to easily return the surveys. On sending back the survey, all participants were mailed a retail gift card worth US$20. The study was considered exempt from institutional review board oversight under exemption category 2 (ie, research involving the use of educational tests (cognitive, diagnostic, aptitude, achievement), survey procedures, interview procedures or observation of public behaviour, and was deemed exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (protocol 820106) as (1) no information obtained is recorded in such a manner that human subjects can be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects and (2) no disclosure of the human subjects’ responses outside the research could reasonably place the subjects at risk of criminal or civil liability or be damaging to the subjects’ financial standing, employability or reputation). All survey responses were securely stored and all identifying information was destroyed once the surveys were returned.

Design of the choice experiment

DCEs have been used extensively to value goods and services for which there is no formal market or only incomplete markets.26 In health and healthcare, these techniques have been applied to address a wide variety of research questions including the elicitation of patients’ preferences, the valuation of health outcomes and the trade-offs between health and non-health benefits of specific.26–28 Importantly, recent studies have used DCEs to investigate the design of financial incentive programmes.24 29–31 DCEs rely on random use theory and are based on the assumption that the value of goods or services is best described by the sum of its attributes (or characteristics) and that people’s choices are driven by the relative value of these characteristics. By presenting respondents with a series of choices between alternatives and by experimentally varying the characteristics of these alternatives, one is able to assess the trade-offs respondents make between product/service characteristics and to measure their influence on choices. A DCE consists of several interdependent steps: defining the attributes and their levels, experimental and survey design, data collection and statistical modelling.26

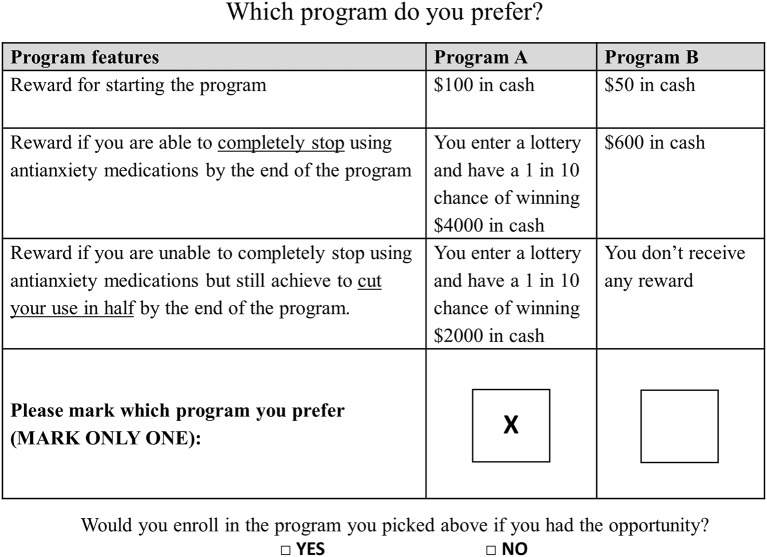

We developed an initial list of potential attributes and levels of the tapering programme via a review of the literature on the design of financial incentives for behavioural change.32 We then refined this list in a series of team meetings and through analysis of pilot data. In the final survey, we described hypothetical tapering programmes using four characteristics: cash reward to start the programme, the incentive amount received conditional on successful discontinuation, whether the conditional incentive was given in the form of a certain cash payment or via a lottery and whether unsuccessful participants would still be rewarded for only cutting their use by half. These attributes and their respective levels are presented in table 1. The next step consisted of combining attributes to form choice sets used to reveal patients’ preferences. Because it would be infeasible to show respondents all possible combinations of attributes and levels (in our case, this would mean 42×22= 64 possible combinations), we generated a fractional factorial design using the N-gene software to obtain a reasonable number of choice sets (ie, 12) that is sufficient to estimate the main effects of interest. We then divided the 12 choice sets into two blocks of 6 choice sets to reduce respondent fatigue, giving rise to two versions of the questionnaire (ie, A and B). While the number of choice sets was not found to be detrimental to DCE data quality,33 we had concerns that this could be an issue in older adults. In each choice set, respondents were asked (1) to choose their preferred tapering programme and (2) to state whether or not they would enrol if such a programme were available to them. As a simple validity check, we also asked respondents if they wanted to be contacted if a similar programme started and gave them the opportunity to provide their contact information. An example of choice set is displayed in figure 1. We also collected information on demographics (ie, age, gender, education, income and household size), history of benzodiazepine use and current level of anxiety (measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item (GAD-7) scale).34

Table 1.

Attributes and levels

| Attributes | Levels | Levels used for the ‘opt-out’ option |

| Cash reward to start the programme (take-up) | US$0, US$10, US$20, US$50 | US$0 |

| Incentive received conditional on successful discontinuation | US$200, US$400, US$600, US$1500 | US$0 |

| Half of the incentive received if use is cut in half | Yes, No | No |

| Incentive format | Certain cash amount, lottery with a 1 in 10 chance of winning | Certain cash amount |

Figure 1.

Example of choice question.

Statistical modelling

We started by describing our patient population and respondents’ choice patterns. We then estimated simple conditional logit models to assess the trade-offs made by individuals between the various programme characteristics, that is, to assess the relative importance of these characteristics when making choices. We jointly modeled programme choice and take-up by including an alternative-specific constant (ASC) for the opt-out option. Due to the limitation of the conditional logit model, which assumes homogeneous preferences in the population, we then estimated more flexible latent class logit models that identify a set of unobserved ‘classes’ or groups of individuals based on observed choice patterns. Separate parameter vectors (and variances) are estimated for each class, which allows for preference heterogeneity across the classes.35–38 Our preferred model, based on the Akaike Information Criteria, included two classes. A feature of the latent class model is that, while we cannot directly observe a respondent’s class membership, we can model the likelihood of class membership as a function of individual characteristics to understand the composition of population classes. We complemented our analyses by predicting programme take-up among survey respondents for a range of incentive amounts for successful discontinuation. This was done by calculating the choice probabilities of each option, including the opt-out, using the latent class model. All analyses were performed using Stata 12.

Results

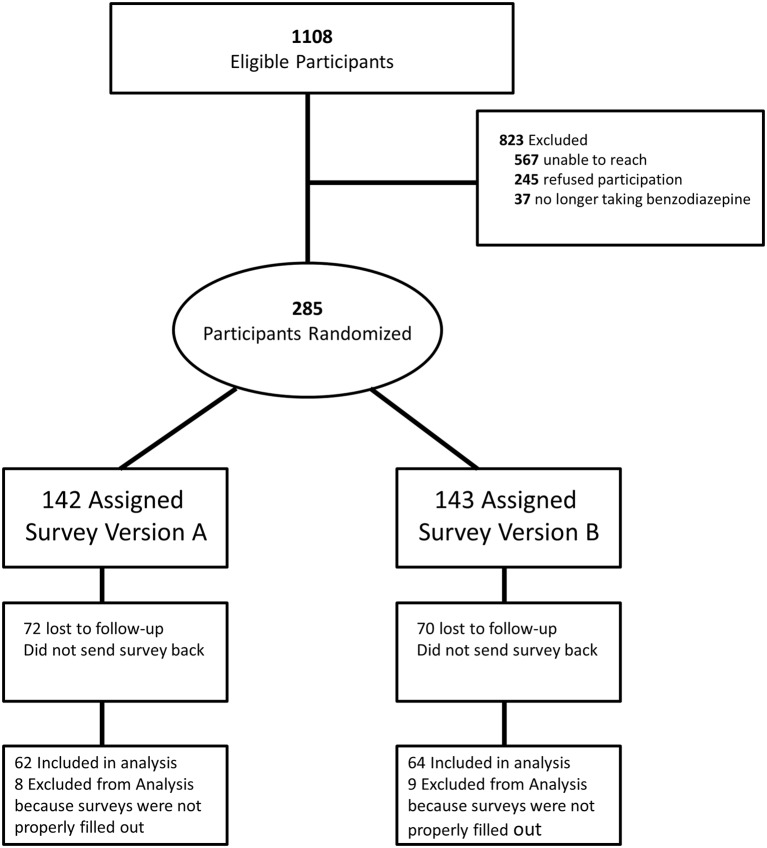

We identified 1108 potentially eligible participants. Of those, we could not reach 567 (reasons included being opted out by provider, invalid phone number, and not answering the phone after three attempts), 245 refused to participate and 37 were ineligible as they were no longer taking benzodiazepines (figure 2). We mailed the survey to the 285 remaining individuals and 143 returned their survey, giving rise to a 28.4% overall response rate (143÷(1108−567−37)) and a 50.2% response rate to the mailed survey among those who provided consent, which is in line with other DCE studies in health using postal surveys.39 We further excluded 17 respondents due to incomplete responses to the choice questions. Therefore, 126 respondents provided complete and usable survey responses.

Figure 2.

Sample flow chart.

The majority of respondents were women (62%) and the average age of respondents was 63 years old (table 2). On average, respondents have been taking benzodiazepines for 10 years, with history of use ranging from 1 to 50 years. The majority of people took benzodiazepines daily or almost daily; only 19% took benzodiazepines once per week or less. Interestingly, 45% of respondents had previously tried to stop taking benzodiazepines. Most respondents (63%) had only minimal or mild anxiety as measured by the GAD-7 scale.

Table 2.

Respondent characteristics (n=126)

| Variables | Mean (IQR) |

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age | 63.4 (57–69) |

| Male | 38% |

| Education: high school or less | 27% |

| Income: less than US$25 000/year | 14% |

| Use of BZD | |

| No of years of use | 9.8 (4–15) |

| Frequency of use | |

| Once per week or less | 19% |

| 1–3 times per week | 18% |

| Almost every day | 13% |

| Every day | 33% |

| Multiple times per day | 16% |

| Ever tried to stop using BZD | 45% |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | |

| Minimal (>4) | 30% |

| Mild (4–9) | 33% |

| Moderate (10–14) | 21% |

| Severe (≥15) | 16% |

| Choice patterns | |

| Would you enrol? | |

| Always ‘yes’ | 49% |

| Always ‘no’ | 29% |

| Average no of ‘yes’ (out of 6) | 3.67 |

| Proportion of ‘yes’ (in all choice situations) | 67% |

| Validity check | |

| Would you like to be contacted if such programme started? | |

| ‘Yes’ in the full sample | 45% |

| ‘Yes’ among those who answered always ‘no’ to the question ‘Would you enrol?’ | 15% |

| ‘Yes’ among those who answered ‘yes’ at least once to the question ‘Would you enrol?’ | 57% |

BZD, benzodiazepine; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item scale.

As an initial investigation of respondents’ preferences, we summarised their general choice patterns. As explained above and shown in figure 1, respondents were first asked to choose their preferred programme and then asked to state their willingness to enrol if such a programme were available. Responses to this second questions provided insight into the general willingness to enrol in incentive programme in this population. Results showed that about 50% of respondents always (ie, in all six choice sets presented) answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Would you enrol in the programme you picked above if you had the opportunity?’ Conversely about 30% of respondents always answered ‘no’ to that question. On average, the proportion of ‘yes’ responses across all respondents and choice sets was 67%, which reflects a fairly high potential enrolment rate among survey respondents. Interestingly, 57% of respondents who answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Would you enrol in the programme you picked above if you had the opportunity?’ at least once expressed an interest in being contacted if such programme started, and shared their contact information.

The results from the conditional logit models shown in table 3 suggest that all studied attributes had an influence on choices. More precisely, as we would expect, the higher the monetary amount for both incentives (start and completion), the higher the probability the respondent would choose that programme. We also observed that respondents tended to favour programmes that offer a reward even if complete discontinuation was not achieved. Finally, respondents in our sample were more likely to choose a programme that offers a cash reward rather than a lottery with equal expected value. While we did not include any choice set aimed at testing respondents’ rationality, we formally investigated attribute dominance (ie, whether for some respondents, choices were driven by a single attribute).40 We identified three respondents who systematically chose the programme with the highest incentive, but have decided not to exclude these as this does not necessarily reflect irrational behaviour.

Table 3.

Choice models

| Model 1: conditional logit | Model 2: latent class logit | |||||

| Utility function | Class 1 (non-traders) | Class 2 | ||||

| Coefficient | 95% CI | Coefficient | 95% CI | Coefficient | 95% CI | |

| Opt-out ASC* | 0.6064 | 0.3274 to 0.8855 | 5.4439 | 3.2462 to 7.6417 | −1.8744 | −2.4692 to −1.2797 |

| Incentive for enrolling | 0.0044 | 0.0016 to 0.0072 | 0.0126 | −0.0103 to 0.0356 | 0.0049 | 0.0018 to 0.0081 |

| Incentive for successful benzodiazepine cessation | 0.0004 | 0.0002 to 0.0006 | 0.0007 | −0.0008 to 0.0022 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 to 0.0007 |

| Half incentive for reducing dose by half | 0.3576 | 0.1623 to 0.5529 | 0.8525 | −1.2748 to 2.9798 | 0.3947 | 0.1825 to 0.6070 |

| Cash rather than lottery | 0.7207 | 0.5213 to 0.9200 | 1.0786 | −0.9806 to 3.1378 | 0.7362 | 0.5208 to 0.9517 |

| Probability of class 1 membership | ||||||

| Age in years (continuous) | −0.0098 | −0.0485 to 0.0288 | ||||

| Years of use (continuous) | 0.0418 | 0.0002 to 0.0739 | ||||

| Gender (male) | −0.7132 | −1.6357 to −0.0093 | ||||

| Education: high school or less | 0.2782 | −0.5978 to 1.1541 | ||||

| Income: less than US$25 000/year | −0.6573 | −1.8428 to −0.0528 | ||||

| Anxiety: severe | −0.0789 | −0.0848 to 0.6900 | ||||

| Class share: | 0.355 | 0.645 | ||||

| N | 126 | |||||

*Alternative-specific constant.

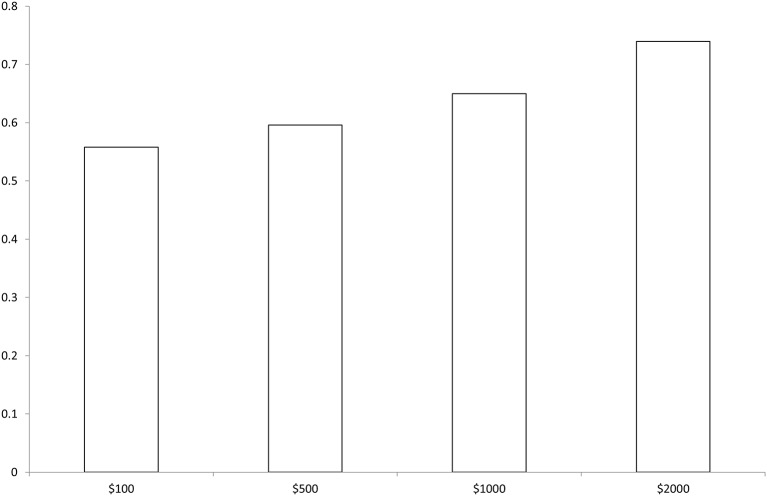

When heterogeneity in preferences is investigated using the latent class model (model 2), we identify two distinct classes (or types) of respondents. Class 1 respondents have a high ASC, that is, a strong preference for opting-out—these individuals can be considered as ‘non-traders’ as it is highly unlikely that they will enrol. We don’t observe any significant impact of programme attributes in this group. These respondents represent 35.5% of the sample, which is in line with the observed rate of 30% in the choice patterns described above. Conversely, Class 2 respondents are responsive to all programme characteristics and are highly likely to choose to enrol. The attributes coefficients are of similar magnitude than in the conditional logit model. The latent class logit framework allows to model the likelihood of class membership as a function of individual characteristics. In other words, we model the probability for respondents to belong to the group of ‘non-traders’ (ie, class 1). We find that male and lower-income respondents were less likely to be non-traders (they are less likely to opt-out) and, perhaps not surprisingly, that respondents with a longer history of benzodiazepine use were more likely to opt-out. Figure 3 shows the predicted choices when the incentive amount for successful discontinuation is varied. The predicted enrolment rate among respondents was around 55.8% with an incentive of US$200 and reached 74% when the incentive is set at US$2000.

Figure 3.

Predicted enrolment by incentive amount for successful discontinuation—Estimated choice probabilities obtained using model 2 in table 3.

Discussion

These results suggest that the enrolment rate among survey respondents for a behavioural economics trial encouraging benzodiazepine taper and discontinuation might range from 56% if the incentive for successful discontinuation was US$200 and up to 74% if the incentive were US$2000. However, as only 28.4% of eligible patients agreed to participate and returned the survey, the real-world enrolment rate among eligible patients might be lower. The choice models indicate that all four studied programme characteristics (amount of cash incentive to start the programme, amount of incentive provided conditional on successful discontinuation, half of the incentive received if the dose is cut in half and incentive format) influenced the probability of choosing a given programme. The expectations regarding the design features of the incentive scheme were largely supported by the results. While higher incentives led to higher predicted uptake, the relationship was not linear, as found previously.24 We also found that respondents strongly favoured cash incentives rather than lotteries of equal expected value and that offering an incentive for reducing the dose by half is likely to increase enrolment. Further, willingness to participate was higher among men and low-income respondents and lower for respondents with a longer history of benzodiazepine use.

We conducted this choice experiment following best practice guidelines41 and within the population of interest, that is, older adults taking benzodiazepines. While our study offers valuable insight into the acceptability and potential take-up of incentive programmes for benzodiazepine discontinuation, it has several limitations. First, while stated preferences surveys have been widely used in health services research, it is important to keep in mind that we are analysing hypothetical choices and therefore our results should be interpreted with caution, as real-world decisions may differ, especially if the setting—in particular features of the health system—differs widely from the US context. Nevertheless, DCEs have been shown to provide relatively accurate predictions of behaviour, with 80% agreement found between stated and revealed preferences.42 43 Also, beyond predicting choices, DCEs are helpful in understanding the relative importance of the various characteristics of the product or service under study. Second, we had an overall response rate of only 28.4%, which may reflect reluctance of people with long-term benzodiazepine use to discontinue.11 Third, as we opted for a paper-based survey, we cannot be certain that respondents did not receive support from friends or relatives to complete it. Finally, to keep the survey at a reasonable level of complexity and to reduce respondent burden, we did not state other potentially relevant features of an incentive programme, such as programme length, contacts with providers or formal record of behavioural change.

This study is the first to provide insight into the acceptability of financial incentives for benzodiazepine discontinuation. Knowing that potential participants are sensitive to the incentive amount for initiating the programme and for successful completion, prefer certain versus lottery payment and prefer partial payment for dose reduction will be helpful in informing the design of future trials. Naturally, even if the intervention were effective in bringing about benzodiazepine discontinuation or dose reduction in a substantial number of participants, the long-term effects on health outcomes such as falls, automobile crashes, cognitive decline and quality of life would need to be demonstrated. Further, an economic evaluation of such a programme would be helpful to assess its financial viability and the potential return on investment/cost-effectiveness. In other words, from a health system perspective, are the benefits to patients in terms of avoided healthcare costs and improved health outcomes from discontinuing benzodiazepines large enough to justify a monetary investment? Recent research has shown that the health benefits (quality of life gained) of some types of drugs are likely to be offset by an increase in future costs, even when limiting the analysis to one category of long-term costs (fall-related costs in this case).44 A comprehensive cost-effectiveness modelling study might help to better understand the potential returns of such investments, both in terms of avoided future costs and increase long-term quality of life.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JM and DM led the design of the choice experiment. MB, JF, MR and SH contributed to the design of the choice experiment. JM performed the statistical analyses and drafted the methods and results sections. MB drafted the introduction. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and manuscript write-up, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: UPenn’s Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics (CHIBE).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (protocol 820106).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Our informed consent document does not permit sharing of patient-level data.

References

- 1. Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, et al. Increasing Benzodiazepine Prescriptions and Overdose Mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health 2016;106:686–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders - first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry 2008;9:248–312. 10.1080/15622970802465807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) in adults: management in primary, secondary and community care. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guideline, 2011:113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. HTA Unit. Clinical practice guideline for treatment of patients with anxiety disorders in primary care. guideline Working Group for the treatment of patients with anxiety disorders in primary Care. Laín Entralgo Agency, Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, 2008:151. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ashton H. Toxicity and adverse consequences of benzodiazepine use. Psychiatr Ann 1995;25:158–65. 10.3928/0048-5713-19950301-09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xing D, et al. A meta-analysis. Osteoporosis International 2014;25:105–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Movig KL, Mathijssen MP, Nagel PH, et al. Psychoactive substance use and the risk of motor vehicle accidents. Accid Anal Prev 2004;36:631–6. 10.1016/S0001-4575(03)00084-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barker MJ, Greenwood KM, Jackson M, et al. Cognitive effects of long-term benzodiazepine use. CNS Drugs 2004;18:37–48. 10.2165/00023210-200418010-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Gage SB, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vikander B, Koechling UM, Borg S, et al. Benzodiazepine tapering: a prospective study. Nord J Psychiatry 2010;64:273–82. 10.3109/08039481003624173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cook JM, Biyanova T, Thompson R, et al. Older primary care patients' willingness to consider discontinuation of chronic benzodiazepines. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007;29:396–401. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Voshaar RC, Couvée JE, van Balkom AJ, et al. Strategies for discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine use: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:213–20. 10.1192/bjp.189.3.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gneezy U, Meier S, Rey-Biel P. When and why incentives (Don’t) Work to modify behavior. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2011;25:191–210. 10.1257/jep.25.4.191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heil SH, Higgins ST, Bernstein IM, et al. Effects of voucher-based incentives on abstinence from cigarette smoking and fetal growth among pregnant women. Addiction 2008;103:1009–18. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02237.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Long JA, Jahnle EC, Richardson DM, et al. Peer mentoring and financial incentives to improve glucose control in African American veterans: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:416–24. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-6-201203200-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, et al. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008;300:2631–7. 10.1001/jama.2008.804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Volpp KG, Loewenstein G, Troxel AB, et al. A test of financial incentives to improve warfarin adherence. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:1 10.1186/1472-6963-8-272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med 2009;360:699–709. 10.1056/NEJMsa0806819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giles EL, Robalino S, McColl E, et al. The effectiveness of financial incentives for health behaviour change: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e90347 10.1371/journal.pone.0090347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Finkelstein EA, Linnan LA, Tate DF, et al. A pilot study testing the effect of different levels of financial incentives on weight loss among overweight employees. J Occup Environ Med 2007;49:981–9. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31813c6dcb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niza C, Rudisill C, Dolan P. Vouchers versus Lotteries: What works best in promoting Chlamydia screening? A cluster randomised controlled trial. Appl Econ Perspect Policy 2014;36:109–24. 10.1093/aepp/ppt033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O’Donoghue T, Rabin M. The economics of immediate gratification. J Behav Decis Mak 2000;13:233–50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Galizzi MM. What is really behavioral in Behavioral Health Policy? and does it work? Appl Econ Perspect Policy 2014;36:25–60. 10.1093/aepp/ppt036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Farooqui MA, Tan YT, Bilger M, et al. Effects of financial incentives on motivating physical activity among older adults: results from a discrete choice experiment. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1 10.1186/1471-2458-14-141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giles EL, Becker F, Ternent L, et al. Acceptability of financial incentives for health behaviours: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One 2016;11:e0157403 10.1371/journal.pone.0157403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ 2012;21:145–72. 10.1002/hec.1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Olsen JA, Smith RD. Theory versus practice: a review of ’willingness-to-pay' in health and health care. Health Econ 2001;10:39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pesko MF, Kenkel DS, Wang H, et al. The effect of potential electronic nicotine delivery system regulations on nicotine product selection. Addiction 2016;111:734–44. 10.1111/add.13257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wanders JOP, Veldwijk J, de Wit GA, et al. The effect of out-of-pocket costs and financial rewards in a discrete choice experiment: an application to lifestyle programs. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1 10.1186/1471-2458-14-870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen TT, Tung TH, Hsueh YS, et al. Measuring Preferences for a Diabetes Pay-for-Performance for Patient (P4P4P) program using a discrete choice experiment. Value Health 2015;18:578–86. 10.1016/j.jval.2015.03.1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morgan H, Hoddinott P, Thomson G, et al. Benefits of Incentives for Breastfeeding and Smoking cessation in pregnancy (BIBS): a mixed-methods study to inform trial design. Health Technol Assess 2015;19:1–522. 10.3310/hta19300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adams J, Giles EL, McColl E, et al. Carrots, sticks and health behaviours: a framework for documenting the complexity of financial incentive interventions to change health behaviours. Health Psychol Rev 2014;8:286–95. 10.1080/17437199.2013.848410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hess S, Hensher DA, Daly A. Not bored yet–revisiting respondent fatigue in stated choice experiments. Transportation research part A: policy and practice 2012;46:626–44. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Determann D, Lambooij MS, de Bekker-Grob EW, et al. What health plans do people prefer? the trade-off between premium and provider choice. Soc Sci Med 2016;165:10–18. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hole AR. Modelling heterogeneity in patients' preferences for the attributes of a general practitioner appointment. J Health Econ 2008;27:1078–94. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mentzakis E, Mestelman S. Hypothetical Bias in value orientations ring games. Econ Lett 2013;120:562–5. 10.1016/j.econlet.2013.06.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sivey P. The effect of waiting time and distance on hospital choice for English cataract patients. Health Econ 2012;21:444–56. 10.1002/hec.1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Watson V, Becker F, de Bekker-Grob E. Discrete choice experiment response rates: a meta-analysis. Health Econ 2017;26:810–7. 10.1002/hec.3354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hensher DA, Collins AT. Interrogation of responses to stated choice experiments: is there sense in what respondents tell Us?: a closer look at what respondents choose and process heuristics used in stated choice experiments. Journal of choice modelling 2011;4:62–89. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health--a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health 2011;14:403–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lambooij MS, Harmsen IA, Veldwijk J, et al. Consistency between stated and revealed preferences: a discrete choice experiment and a behavioural experiment on vaccination behaviour compared. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015;15:1 10.1186/s12874-015-0010-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Salampessy BH, Veldwijk J, Jantine Schuit A, et al. The predictive value of discrete choice experiments in public health: an exploratory application. Patient 2015;8:521–9. 10.1007/s40271-015-0115-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tannenbaum C, Diaby V, Singh D, et al. Sedative-hypnotic medicines and falls in community-dwelling older adults: a cost-effectiveness (decision-tree) analysis from a US Medicare perspective. Drugs Aging 2015;32:305–14. 10.1007/s40266-015-0251-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.