Abstract

Objective

To review and synthesise qualitative literature relating to the longer-term needs of community dwelling stroke survivors with communication difficulties including aphasia, dysarthria and apraxia of speech.

Design

Systematic review and thematic synthesis.

Method

We included studies employing qualitative methodology which focused on the perceived or expressed needs, views or experiences of stroke survivors with communication difficulties in relation to the day-to-day management of their condition following hospital discharge. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, The Cochrane Library, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences and AMED and undertook grey literature searches. Studies were assessed for methodological quality by two researchers independently and the findings were combined using thematic synthesis.

Results

Thirty-two studies were included in the thematic synthesis. The synthesis reveals the ongoing difficulties stroke survivors can experience in coming to terms with the loss of communication and in adapting to life with a communication difficulty. While some were able to adjust, others struggled to maintain their social networks and to participate in activities which were meaningful to them. The challenges experienced by stroke survivors with communication difficulties persisted for many years poststroke. Four themes relating to longer-term need were developed: managing communication outside of the home, creating a meaningful role, creating or maintaining a support network and taking control and actively moving forward with life.

Conclusions

Understanding the experiences of stroke survivors with communication difficulties is vital for ensuring that longer-term care is designed according to their needs. Wider psychosocial factors must be considered in the rehabilitation of people with poststroke communication difficulties. Self-management interventions may be appropriate to help this subgroup of stroke survivors manage their condition in the longer-term; however, such approaches must be designed to help survivors to manage the unique psychosocial consequences of poststroke communication difficulties.

Keywords: systematic review, stroke, aphasia, dysarthria, apraxia of speech

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies to explore the longer-term needs of stroke survivors with communication difficulties living in the community.

By synthesising qualitative literature, a greater level of conceptual or theoretical understanding can be gained than by looking at one study in isolation.

Thematic synthesis is a robust method of synthesis, which draws together information from qualitative literature in order to make reasoned recommendations for future intervention development.

Many of the studies identified did not describe the role of the researcher, which may impact on the data collected and the findings of the synthesis.

The impact of publication bias in qualitative literature is difficult to assess.

Introduction

The global burden of stroke is set to rise. It is predicted that by 2030, there will be 12 million stroke deaths, 70 million stroke survivors and 200 million disability adjusted life-years lost due to stroke worldwide.1 In England, it is estimated that 300 000 people are living with moderate-to-severe disability following stroke.2 The disabilities stroke survivors face are complex and there is a high prevalence of unmet need in the years following acute onset.3 Qualitative research has identified that the transition between hospital and community services is difficult and that many stroke survivors feel unsupported and abandoned in the longer-term.4–6 Although the importance of supporting stroke survivors in the longer-term has been recognised by policy makers, the precise format and content of such support has yet to be established.2 7 8 Developing an evidence-based care pathway that meets the complex needs of individuals and families coping with the aftermath of stroke remains a challenge.9–11

Up to one-third of survivors will experience communication difficulties poststroke including aphasia, dysarthria or apraxia of speech12–15 resulting in difficulties with language comprehension, speech production and difficulties with reading and writing. Research suggests that this subgroup of stroke survivors may have particularly poor longer-term outcome,16 for example, stroke survivors with aphasia living in the community have reduced quality of life compared with those without and participate in fewer activities of daily living.17 This subgroup are also more likely to suffer from depression18 and have reduced social interactions.19 Although stroke survivors with communication difficulties may benefit from longer-term support, the needs of this population in relation to longer-term care have not been explored.

Qualitative research provides in-depth accounts of the views, meanings and experiences of patients and is increasingly seen as an important contributor to complex intervention development.20–22 In the wider stroke literature, systematic reviews and syntheses of qualitative literature have been undertaken.23–25 However, Walsh et al25 and Satink et al24 noted the lack of studies involving stroke survivors with communication difficulties and therefore it is unclear if the findings from such reviews can be generalised to this population. More recently, researchers have developed strategies to ensure that, wherever possible, those with communication difficulties can be included in qualitative research.26–28 There is a growing body of research in this field that highlights the stroke survivors perspective on living with a communication difficulty.29 A recent narrative literature review drew together qualitative studies exploring stroke survivor’s experiences of community aphasia groups (CAGs).30 This review focused specifically on experiences of CAGs and did not attempt to synthesise broader experiences of living with a communication difficulty. To date, there has been no systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research exploring the needs of stroke survivors with communication difficulties in relation to longer-term care.

Systematic reviews of qualitative research draw together study findings, allowing a greater level of conceptual or theoretical understanding than can be gained by looking at one study in isolation.31 32 Qualitative synthesis aims to go beyond a descriptive summary or aggregation of study findings and create an overall interpretation of the literature. This review uses thematic synthesis,33 which clearly distinguishes between synthesis at a descriptive and interpretive level. Two types of themes are developed: descriptive themes that are a summary of findings across included studies and analytical themes, which translate or interpret study findings with regard to the research question. By creating an overall interpretation of the literature in relation to a particular research focus, the findings can inform future intervention development, clinical practice and policy.31 32 In order to design a longer-term care strategy for stroke survivors with communication difficulties, it is important to synthesise qualitative research findings to better understand the requirements for longer-term care from the patients’ perspective. This review aimed to explore the needs of stroke survivors with communication difficulties in relation to longer-term care.

Method

A systematic review and thematic synthesis33 of qualitative literature relating to the needs of stroke survivors with communication difficulties living in the community was undertaken. A review protocol was developed but was not registered or published.

Eligibility criteria

Study design: studies published in English, employing qualitative methodology and qualitative methods of data analysis.

Population: adults (aged 16+ years) with communication difficulties following stroke (aphasia, dysarthria or apraxia of speech).

Outcomes: the perceived or expressed needs, views or experiences of stroke survivors with communication difficulties in relation to the day-to-day management of their condition following hospital discharge (including studies in which carers, friends or relatives shared their perspectives on the needs, views or experiences of stroke survivors). Studies were excluded where the focus was on the delivery or evaluation of a specific communication intervention.

Search terms

Search terms were developed with an information specialist using an iterative process including scoping searches and repeated piloting. In traditional reviews of effectiveness, methods and filters for identifying randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are well established. However, qualitative research is often indexed inconsistently across databases and is difficult to pick up using free text search terms due to the use of creative titles and focus on findings (as opposed to methods) in abstracts.34 This poses difficulties when identifying qualitative research systematically.35–37 Some argue for the use of a broader approach by not including filters in relation to qualitative methodology.38 However, in this case a qualitative filter39 was applied due to the unmanageable numbers of citations (48 000) initially returned. This potential limitation was addressed by ensuring that multiple search strategies were used. Search terms were initially developed and run in Ovid Medline and then adapted according to the capabilities of each database. A copy of the search terms is available in the online supplementary material.

bmjopen-2017-017944supp001.pdf (58.8KB, pdf)

Information sources

The following databases of published literature were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), The Cochrane Library, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences and Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED). To limit publication bias, the following grey literature sources were searched: Index to Theses (UK dissertations and Theses), ProQuest (international dissertations and theses) and Web of Science conference proceedings. Searches were conducted week commencing 2 February (week 5, 2015) and databases were searched from inception. To ensure that the search was comprehensive, other search strategies were also implemented including: 1) reviewing the reference lists of studies meeting inclusion criteria, 2) reverse citation search of studies meeting inclusion criteria and 3) reference list check and reverse citation search of an existing systematic review of qualitative literature in stroke care.40

Study selection and data extraction

Studies were screened and selected firstly based on title and abstract review and then selected following full text review. Title and full-text screening and selection was performed independently by the first author and another researcher for all studies. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with the second and third authors.

Data extracted included study aim(s), participant characteristics (age, gender, type of communication difficulty, time poststroke), sample size, country, study setting and methodology (method of data collection, method of analysis). Findings of included studies were also used to inform the thematic synthesis (see data synthesis). Double data extraction was completed for 30% of the included studies and compared to ensure agreement levels were high.

Quality assessment

There is substantial debate concerning the criteria that should be used to determine study quality in qualitative research.41 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) public health guidance qualitative appraisal checklist42 was used for assessment of methodological quality in the current review. NICE created the checklist based on the broad issues, which are generally accepted to affect validity in qualitative research.42 The checklist comprises 14 domains including theoretical rationale (appropriateness, clarity), study design, data collection, trustworthiness (role of the researcher, context, reliable methods), analysis (rigorous, rich data, reliable, convincing, relevance to aims), conclusions and ethics. The researcher may endorse the presence or absence of the domain characteristic or mark as unclear/not reported. The checklist also has an overall assessment of study quality that can be marked (++) ‘All or most of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled, where they have not been fulfilled the conclusions are very unlikely to alter’ or (+) ‘Some of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled, where they have not been fulfilled, or not adequately described, the conclusions are unlikely to alter’ or (−) ‘Few or no checklist criteria have been fulfilled and the conclusions are likely or very likely to alter’. In addition to being completed by one researcher, quality assessment was performed by a second researcher for 30% of the included studies. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus by a third reviewer and remaining quality assessments were revised in line with the discussion to ensure consistency.

Quality assessment was not used to exclude studies but to highlight potential limitations of the research. Although all studies were included in the data synthesis, the findings of lower quality studies were reviewed to ensure that they did not contradict the findings of higher quality studies and to ensure that they did not make a disproportionate contribution to the development of the thematic synthesis.

Data synthesis

There is no consensus on the most appropriate method for the synthesis of qualitative data35 43 and a number of approaches have been developed including qualitative meta-synthesis,44 meta-ethnography31 32 and thematic synthesis.33 38 In this review, studies were combined using thematic synthesis.33 38 This method of synthesis was specifically formulated by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre to organise findings from qualitative literature to enable reasoned hypotheses about intervention need, appropriateness and acceptability.45 Like meta-synthesis and meta-ethnography, thematic synthesis allows for a deeper exploration of findings which goes beyond narrative summary.33 38 Unlike meta-synthesis and meta-ethnography, thematic synthesis transparently reports the descriptive and interpretive levels of synthesis; distinguishing between the ‘data-driven’ descriptive themes and ‘theory-driven’ analytical themes. In thematic synthesis, the review question provides the theoretical framework to drive the development of the analytical themes. This differs from other methods of synthesis (eg, grounded theory or meta-ethnography), which focus on theory generation without a pre-existing framework and without the explicit intention to inform intervention development.31 46

Key findings (supported by relevant quotations) from each included study were extracted and free coded line by line using QSR NVivo software V.10. Groups of descriptive codes were formed based on similarities between the free codes. Through discussion with a second reviewer and a wider review team, the contents of each of the groups of descriptive codes were explored and further refined to create descriptive themes.33 38 Analytical themes were developed through an iterative process, which included discussion of the links between the descriptive themes and the implications of these on the needs of stroke survivors with communication difficulties and future intervention development.24 33 47 Analytical themes were developed with help from the wider review team and by gaining feedback on draft analytical themes from a peer-review group in the research unit.

Results

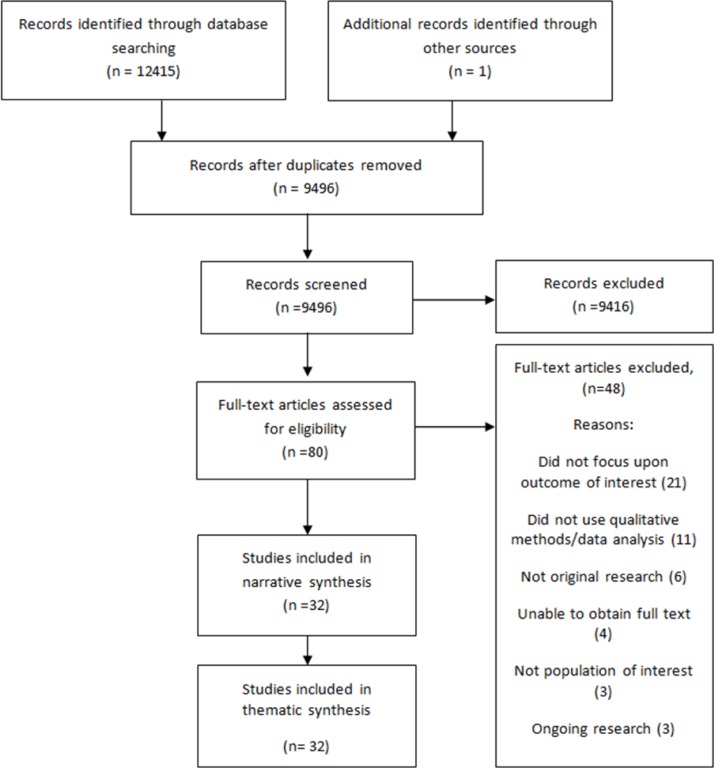

Thirty-two citations were identified which were eligible for inclusion in the review.48–79 The Prefered Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of study selection is shown in figure 1. Once duplicates had been removed, 9496 records were screened for eligibility and full text was sought for 80 citations; 48 were excluded; 21 studies which did not focus on the outcome of interest,80–100 11 studies which did not use qualitative methods or qualitative methods of data analysis,6 101–111which were not original research (eg, were commentaries or book reviews),112–117 4 for which we were unable to obtain full text,118–121 3 which did not include the population of interest122–124 and 3 ongoing pieces of research for which the results were not yet available.125–127

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of included studies.

Outcomes: Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Authors | Aim of study | L&C difficulty | Size | Country | Setting | Age range | Gender | Time poststroke | Method of data collection | Time points | Method of analysis | Overall assessment of methodological quality |

| Baylor et al48 | To explore the similarities and differences in self-reported restrictions in communicative participation across different communication disorders in community-dwelling adults | Aphasia, apraxia of speech, dysarthria | 44 | USA | Community | 37–88 | 21 males 23 females |

Mean 8.2 years (SD 7.4, range 0.5–24) | Interview | One interview | Content analysis | - |

| Brady et al50 | To explore the impact of dysarthria on social participation following stroke | Dysarthria | 24 | UK | Community | 34–86 | 15 males 9 females |

Mean (months) 8 (SD 7, range 2–34) | Interview | One interview | Grounded theory | + |

| Brady et al49 | To explore the perceptions of people with stroke-related dysarthria in relation to the management and rehabilitation of dysarthria | Dysarthria | 24 | UK | Community | 34–86 | 15 males 9 females |

Up to 3 years (mean not reported) | Interview | One interview | Grounded theory | + |

| Brown et al52 | To explore from the perspectives of people with aphasia, the meaning of living successfully with aphasia | Aphasia | 25 | Australia | Community | 38–86 | 13 males 12 females |

Mean (months): 71.5 (SD 62.3, range 24–299) | Interviews and participant generated photography | Two interviews | Interpretive phenomenological analysis | ++ |

| Brown et al53 | To explore from the perspectives of family members of individuals with aphasia, the meaning of living successfully with aphasia | Aphasia | 24 | Australia | Community | 40–87 | 9 males 15 females |

? | Interview | One interview | Interpretive phenomenological analysis | ++ |

| Brown et al51 | To explore the perspectives of 25 community dwelling individuals with chronic aphasia on the role of friendship in living successfully with aphasia | Aphasia | 25 | Australia | Community | 38–86 | 13 males 12 females |

Mean (months): 71.5 (SD 62.3, range 24–299) | Interviews and participant generated photography | Two interviews | Thematic analysis | + |

| Cruice et al54 | To explore how older people with chronic aphasia who are living in the community describe their quality of life in terms of what contributes and what detracts from the quality in their current and future lives | Aphasia | 30 | Australia | Community | 57–88 | 14 males 16 females |

Mean (months): 41 (SD 25.6, range 10–108) | Interview | One interview | Content analysis | + |

| Cyr55 | To investigate factors associated with resilience in individuals with aphasia | Aphasia | 9 | USA | Community | 47–73 | ? | ? | Interview | One interview | Content analysis | - |

| Dalemans et al56 | To explore how people with aphasia perceive participation in society and to investigate influencing factors | Aphasia | 13 | The Netherlands | Community | 45–71 | 7 males 6 females |

Range (years): 1–11 | Interview and diary | One interview. Diary kept for 2 weeks prior to interview | ? | ++ |

| Davidson et al57 | To describe everyday communication with friends for older people with and without aphasia and to examine the nature of actual friendship conversations involving a person with aphasia | Aphasia | 15 | Australia | Community | 64–80 | 7 males 8 females |

Mean (months) 42.13 (SD 27.70) | Observation and communication diary (phase I) Qualitative interview data from simulated recall (phase II) |

Three separate observations for a total of 8 hours on 1 week Diary kept on 5 consecutive days |

Inductive interpretive analysis (phase I) Systematic qualitative analysis (phase II) |

+ |

| Davidson et al58 | To explore the insider perspective on the impact of aphasia on social communication and social relationships, and to explore components of the interactional function of everyday communication that are identified by older people with aphasia | Aphasia | 3 | Australia | Community | 69–84 | 1 male 2 females |

? | Interviews and diary data | One qualitative interview, one stimulated recall interview regarding a previously videotaped recording of an interaction with a communication partner, diary about communication kept for 7 days | Qualitative interview and stimulated recall interview: framework analysis diary: analysed following guidance by Code (2003) |

+ |

| Dickson et al59 | To investigate the beliefs and experiences of people with dysarthria as a result of stroke in relation to their speech disorder, and to explore the perceived physical, personal and psychosocial impacts of living with dysarthria | Dysarthria | 24 | UK | Community | 34–86 | 15 males 9 females |

Mean (months) 7.07 (range 2–34) | Interview | One interview | Grounded theory | + |

| Dietz et al60 | To (a) explore the social role changes experienced by people with aphasia, (b) understand the use of communication strategies when attempting to reclaim previous roles and (c) determine whether discrepancies existed between PWA and their potential proxies regarding social role change changes/adaptations | Aphasia | 3 | USA | Community | 41–85 | 2 males 1 female |

Range (months): 24–180 | Interview | One interview | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | + |

| Fotiadou et al61 | To explore the impact of stroke and aphasia on a persons relationships with family, friends and the wider network through analysing blogs written by people with aphasia | Aphasia | 10 | USA, UK, Turkey | Community | 29–69 | 4 males 6 females |

At least 1 year (mean not reported) | Analysis of online blogs | N/A | Framework analysis | ++ |

| Grohn et al63 | To describe the experience of the first 3 months poststroke in order to identify factors which facilitate successfully living with aphasia | Aphasia | 15 | Australia | Community | 47–90 | 8 males 7 females |

3 months (±2 weeks) | Interview | 3 months poststroke | Thematic analysis | ++ |

| Grohn et al62 | To describe the insiders perspective of what is important to living successfully with aphasia and changes that occur throughout the first year poststroke | Aphasia | 15 | Australia | Community | 47–90 | 8 males 7 females |

3, 6, 9, 12 months | Interviews | 3, 6, 9, 12 months poststroke | Thematic analysis | ++ |

| Hinckley64 | The question ‘what does it take to live successfully with aphasia?’ was posed and answers sought within already published accounts written by people living successfully with aphasia | Aphasia | 20 | ? | Community | ? | ? | ? | Analysis of published personal narratives | N/A | Thematic analysis | + |

| Howe et al66 | To explore the environmental factors that hinder or support the community participation of adults with aphasia | Aphasia | 25 | Australia | Community | 34–85 | 15 males 10 females |

Mean (months) 66.6 (SD 34.4, range 10–137) | Interviews | One interview | Content analysis | ++ |

| Howe et al65 | To explore the environmental factors that hinder or support the community participation of adults with aphasia | Aphasia | 10 | Australia | Community | 35–72 | 6 males 4 females |

Mean (months) 97.1 (SD 29.2, range 51–155) | Observation | Approximately 3 hours of observation | Content analysis | ++ |

| Johansson et al67 | To explore how people with aphasia experience having conversations, how they handle communication difficulties and how they perceive their own and their communication partners use of communication strategies | Aphasia | 11 | Sweden | Community | 48–79 | 7 males 4 females |

Mean (months) 38 (range 13–75) | Interviews | One interview | Content analysis | ++ |

| Le Dorze and Brassard69 | (1) To understand the consequences of aphasia in the terms used by aphasic persons and their friends and relatives to describe their experience of this communication disorder (2) To qualitatively analyse and structure the different descriptions with the concepts of impairment, disability handicap and coping behaviour |

Aphasia | 9 | Canada | Community | 44–69 | 5 males 4 females |

Mean (years) 5.5 (range 2–14) | Interviews | One interview | Grounded theory | + |

| Le Dorze et al68 | To explore with a qualitative approach the experience of auditory comprehension problems from the perspective of aphasic persons and their family and friends | Aphasia | 24 | Canada | Community | 33–71 | 10 males 14 females |

Mean (months) 55.96 (range 4–147) | Focus group | One focus group | Phenomenological | - |

| Le Dorze et al70 | To explore the factors that facilitate or hinder participation according to people who live with aphasia | Aphasia | 17 | Canada | Community | 51–84 | 12 males 5 females |

Mean (years) 5.7 (range 2–18) | Focus group | One focus group | Content analysis | + |

| Matos et al71 | To explore and understand the perspectives of Portuguese people with aphasia, family members and speech and language therapists | Aphasia | 14 | Portugal | Community | 41–80 | 11 males 3 females |

Mean (months) 27.57 (range 3–89) | Group and individual interviews | Participants with mild-to-moderate aphasia were interviewed as a group and those with severe aphasia were interviewed individually | Thematic analysis | + |

| Nätterlund72 | To describe aphasic individuals’ experiences of everyday activities and social support in daily life | Aphasia | 20 | Sweden | Community | 32–70 | 14 males 6 females |

Mean (years) 6.52 (range 3–11 years) | Interview | One interview | Content analysis | ++ |

| Niemi and Johansson73 | To describe and explore how persons with aphasia following stroke experience engaging in everyday occupations | Aphasia | 6 | Finland | Community | 46–75 | 3 males 3 females |

Mean (years) 2.5 (range 1–4) | Interviews | 2–3 interviews over 2 months | Empirical phenomenological analysis | + |

| Parr74 | To describe the consequences and significance of long-term aphasia | Aphasia | 50 | UK | Community | ? | 28 males 22 females |

Mean (years) 7.7 (range 5–21) | Interview | One interview | Framework method | + |

| Parr75 | To track the day-to-day life and experiences of people with severe aphasia, and to document levels of social inclusion and exclusion as they occurred in mundane settings | Aphasia | 20 | UK | Community | 33–91 | 11 males 9 females |

Mean (years) 4.67 (range 0.9–15) | Ethnography | Visited and observed three times in different domestic and care settings | Framework method | - |

| Pound76 | To investigate how people with aphasia understand friends and friendship | Aphasia | 28 | UK | Community | ? | Phase I: 6 males, 6 females Phase II: ? |

Phase I: mean (years) 7.46 (range 1.5–20) Phase II: ? |

Interview | One interview per participant in each phase | Thematic analysis | ++ |

| Pringle et al77 | To gain a greater understanding of the experience of returning home for stroke survivors and their carers | Aphasia | 4 | UK | Community | ? | ? | 1 month | Interviews and self-report diaries | One interview and diary | Phenomenological approach | - |

| Runne78 | To examine the relationship between self-efficacy and a person’s choice to participate in life roles involving communication by inviting the experts (ie, people with speech and language disorders) to share their experiences | Aphasia and dysarthria | 5 | USA | Community | 51–69 | 2 males 3 females |

Mean (years) 8 (range 3–14) | Interview | One interview | Thematic analysis | - |

| Worrall et al79 | To describe the goals of people with aphasia and to code the goals according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health | Aphasia | 50 | Australia | Community | ? | 24 males 26 females |

Mean (months) 54.9 (SD 43.6) | Interview | One interview | Qualitative content analysis | + |

?, insufficient information; N/A, not applicable.

The experiences of 518 stroke survivors with communication difficulties were reported. Studies reporting gender included 249 male and 220 female participants; age ranged from 29 to 91 years. Sample sizes ranged from 360 104 to 50.74 79 The majority of studies identified included participants with aphasia (29 out of 32). Only five studies reported including participants with dysarthria48–50 59 78 and one study included participants with apraxia of speech.48 The time poststroke varied; the participants in 21 studies had a mean time poststroke of >12 months and the participants in 5 studies had a mean time poststroke of <12 months.49 59 62 63 77

Methodological quality of included studies

Table 2 shows the results from the NICE public health qualitative appraisal checklist.42 A table showing individual study ratings is included in the online supplementary material.

Table 2.

Methodological quality of included studies

| Appropriate | Inappropriate | Not sure | |

| 1. Theoretical rationale: appropriateness | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| Clear | Unclear | Mixed | |

| 2. Theoretical rationale: clarity | 28 | 1 | 3 |

| Defensible | Indefensible | Not sure | |

| 3. Study design | 21 | 4 | 7 |

| Appropriately | Inappropriately | Not sure/inadequately reported | |

| 4. Data collection | 30 | 1 | 1 |

| Clearly described | Unclear | Not described | |

| 5. Trustworthiness: role of the researcher | 5 | 2 | 25 |

| Clear | Unclear | Not Sure | |

| 6. Trustworthiness: context | 27 | 5 | 0 |

| Reliable | Unreliable | Not sure | |

| 7. Trustworthiness: reliable methods | 29 | 1 | 2 |

| Rigorous | Not rigorous | Not sure/not reported | |

| 8. Analysis: rigorous | 20 | 2 | 10 |

| Rich | Poor | Not sure/not reported | |

| 9. Analysis: rich data | 22 | 8 | 2 |

| Reliable | Unreliable | Not sure/not reported | |

| 10. Analysis: reliable | 17 | 1 | 14 |

| Convincing | Not convincing | Not sure | |

| 11. Analysis: convincing | 22 | 5 | 5 |

| Relevant | Irrelevant | Partially relevant | |

| 12. Analysis: relevance to aims | 28 | 0 | 4 |

| Adequate | Inadequate | Not sure | |

| 13. Conclusions | 28 | 3 | 1 |

| Appropriate | Inappropriate | Not sure/not reported | |

| 14. Ethics | 20 | 1 | 11 |

| ++ | + | - | |

| Overall assessment | 12 | 14 | 6 |

The majority of studies performed well across the domains. Studies performed less well in domain 5 (trustworthiness: role of the researcher). In this domain, only 5 out of 32 studies reflected on the role of the researcher in the research.52 62 65 66 73 In just under half of the studies (14 out of 32), it was unclear if the methods used for the analysis were reliable (domain 10).49 50 57–60 65 67 72–75 77 79 Eight studies were classified as having ‘poor’ quality data in domain 9 (analysis: rich data) failing to provide enough depth and detail to provide convincing insight into participants' experiences.48 54 55 68 69 71 77 79 In 11 studies, the ethical implications of the research were not adequately reported.48 53 57 58 60 64 68 69 74 78 79

Six studies were scored in the lowest category for the overall assessment (−).48 55 68 75 77 78 Of these, three studies were narrow in description and lacked richness in the data presented.48 68 77 The remaining three studies55 75 78 were problematic in their overall conclusions. Twenty-six out of 32 studies were scored in the (+) or (++) categories, suggesting that they scored satisfactorily on most items of the checklist or where they had not, the conclusions of the study were unlikely to be altered.

Thematic synthesis

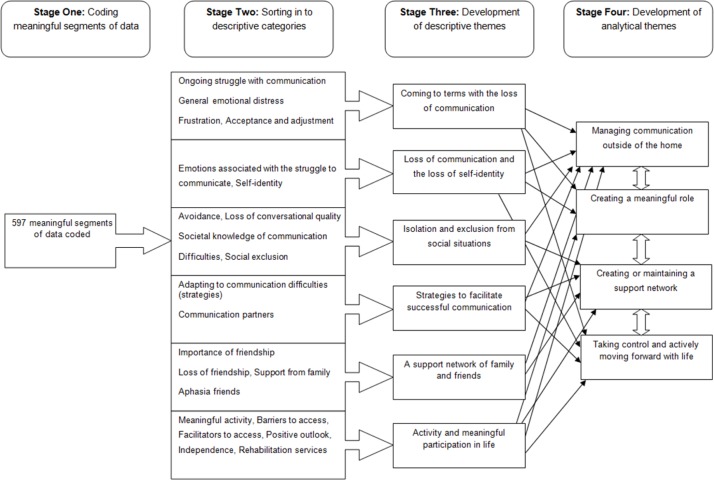

The progression from descriptive to analytical themes is illustrated in figure 2. Free coding the findings of included studies produced 597 meaningful segments of data; these were grouped together according to similarity and new descriptive categories were created to capture the meaning of the grouped free codes. For example, free codes which captured emotions (such as loss, anger and sadness) related to the struggle to communicate were grouped to form the descriptive category ‘Emotions associated with struggle to communicate’. The initial codes were grouped in to 22 descriptive group categories. Meanings were refined and themes developed by reassessing the data contained within each category to create descriptive themes. For example, an overlap in experiences was seen between the emotions associated with struggle to communicate and the self-identity category. This developed in to the descriptive theme of ‘loss of communication and the loss of self-identity’. Although the current review aimed to identify the needs of stroke survivors with communication difficulties, the studies identified did not ask participants directly about their needs and participants did not describe their experiences in terms of need. However, based on the experiences described, analytical themes were developed which inferred and theorised about the needs of stroke survivors with communication difficulties and the impact this may have on future intervention development.33 38

Figure 2.

The development of descriptive and analytical themes.

Descriptive themes

Six descriptive themes were developed and are illustrated in table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive themes

| Descriptive theme | Illustrative quote(s) | |

| Coming to terms with the loss of communication | The extent to which stroke survivors reported being able to come to terms with a communication impairment varied.52 54 55 60 61 64 71 73 For some, the struggle to communicate was an ongoing source of emotional distress, triggering feelings of grief, loss and sadness. However, others had successfully come to terms with their communication impairments. These participants recognised the changes that had taken place in their lives but had been able to adjust to these and find contentment. |

"What if you only could! Could talk! That’s what I… Everything" (p. 149)67

"And I know it’ll never be the same as what I was before I had the stroke … And as I say I hate to accept it, but I’ve got to accept it". (p. 1283)52 |

| Loss of communication and the loss of self-identity | Communication was often linked to participants sense of self. Being able to communicate as before was regarded as being ‘normal’50 59 and since stroke some participants described feeling as though a piece of themselves was missing. Stroke survivors were conscious of the deficiencies in their speech. The constant monitoring and evaluation of speech was also linked to negative self-evaluation when stroke survivors fell short of their own expectations. |

"at least 50 percent of me vanished when speech vanished that that’s how I think about it" (p. 1831)73

"… I hate myself because I can’t speak right…" (p. 143)59 |

| Isolation and exclusion from social situations | Participants felt left out of social situations or ignored or excluded specifically due to their communication problems.48–50 56 57 59–61 65–73 75 The discomfort others felt in talking to stroke survivors with communication difficulties was apparent to the stroke survivor themselves and led to feelings of social isolation. Participants expressed particular difficulty in taking part in group situations.56 61 68–70 As a consequence, people with poststroke communication difficulties described either withdrawing from or avoiding communication or social situations altogether.48–50 59–61 68 70 71 Feelings of embarrassment and a lack of confidence in communication contributed to participant’s avoidance of social events.50 One participant also suggests that fear of stigmatising reactions contributed to avoidance of social situations.50 |

"It’s my wife who says I’m antisocial because, even when I visit my in-laws, I’m sick of going to their parties, sit in a corner, and at the end of the party, I get up and leave. I haven’t said a damn word in there, and no one was interested, talked to me". (p. 431)70

"Instead, they would ‘go into the background and retreat’…. and ‘do the bare amount of talking’…" (p. 275)48 |

| A support network of family and friends | Family members were discussed as an ongoing support on a practical and emotional level.62 70 Although some survivors did rely more on family members for support since having their stroke, reliance on others was not desired by stroke survivors or their carers.56 60 61 63 67 70 73 79 The importance of friendship and social support outside the family was also expressed by stroke survivors with communication impairments.51–55 57 61 63 64 72 76 However, also prominent was the difficulty maintaining friendships and the loss of friendship poststroke.52 56 61 69–72 75 76 |

"The informants mentioned that being dependent on their partners was frustrating. Having their partner always nearby brought security but it also made them feel that they were being a burden". (p. 150)67

"…Friends stayed away because they didn’t know how to handle the new situation. When time passed by, making contact became even more difficult…" (p. 543)56 |

| Strategies to facilitate successful communication | Some stroke survivors with communication difficulties used their own strategies to help facilitate conversation.48 49 52 56 60 65 67 69 78 A wide range of strategies were identified including communication aids,49 52 56 60 drawing or writing information down49 52 67 and signalling by raising a hand that they have something to add when in a group situation.48 49 69 However, some studies identified a stigma attached to using communication aids.56 67 Strategies used by communication partners of people with poststroke communication difficulties were also recognised as a facilitator to successful communication.49 52 56–58 63 65 67 68 73 74 77 78 |

"Interviewer: do you use a communication book? Liv: no, people look strange". (p. 544)56

"Equally important were the degree to which the CPs were able to adapt their speaking behaviour and whether they used supportive conversation strategies. ’Then she wrote! Keywords like this. – – – She wrote for me, you see. – – – That was damn good, and then I understood at once!'…" (p. 1287)52 |

| Activity and meaningful participation in life | A distinction can be made between stroke survivors who took part in activities they enjoyed or which were meaningful to them and those who no longer took part and remained largely inactive. Where stroke survivors engaged in activities they valued, a sense of achievement, purpose, pleasure and confidence was expressed.49 52 53 55 56 62 63 76 Establishing a routine was important to stroke survivors with aphasia. Again this gave stroke survivors a sense of purpose and achievement, which was not evident in the experiences of those participants where activity had decreased poststroke.54 60 61 69 71–73 75 |

"’Be involved with everything'. ’Have a hobby'. ’Live as much as you can; do as much as you can'". (p. 1277)52

"When able to establish a routine and engage in activities around the home, participants often obtained a sense of ability, competency and independence: ‘I can do everything for myself’ and ‘I can do it myself. Pretty well'". (p. 1415)62 |

Analytical themes

Four analytical themes were developed and are described below. It is important to note that the needs highlighted are interconnected and there is significant overlap between themes. For example, the ability to create a meaningful role may be influenced by the availability of a support network or by ability to communicate outside of the home.

Managing communication outside of the home

Managing communication outside of the home was a salient issue for many of the participants in the included studies. Where difficulties with communication arose, these generally occurred away from the safety of the home environment. Many participants were self-conscious about speaking in public and some took steps to hide their communication difficulty by avoiding social interaction completely or by using the bare minimum amount of communication required.49 50 56 59–61 67 69–71 74 75 77 79 This protected participants from stigmatising reactions and also protected participants self-identity which was questioned when they were confronted with their communication difficulties.49 50 59 73 However, by avoiding communicative situations, stroke survivors put themselves at risk of losing friendships and becoming socially isolated.51 52 56 61 69–72 75 76

In contrast, rather than avoiding communication, some stroke survivors identified the active use of strategies to adapt their communication and make themselves understood outside of the home, for example, communication aids,49 52 56 60 78 drawing or writing information down49 52 67 78 or signalling by raising a hand that they have something to add when in group situation.48 49 69 78 Other strategies used to facilitate successful communication included sticking to familiar places or people. For example, in one study, when describing the routine of one participant going out for a coffee this was facilitated by the coffee shop staff’s knowledge of that individual.65 Successful interaction was often facilitated by the stroke survivors close family members, for example, a participant in Brady et al49 stated "(She) (Wife) deciphers for me" (p. 945). Successful interaction could also be facilitated by a competent conversation partner.49 52 56 57 63 65 67 68 73 74 77 78 Successful interaction helped participants to gain a sense of self-confidence and self-worth:

It feels really nice that someone… someone that just wants to speak with you! One feels like a human being. It feels ‘Wow!’…67 (p. 148)

Future interventions should support stroke survivors to build confidence in their communicative abilities in order to rebuild their sense of self. A staged programme whereby stroke survivors are supported to build confidence in their communicative abilities through setting tasks with increasing difficulty may be appropriate.128 For example, the stroke survivor may progress in stages from one-to-one communication with someone familiar to communicating outside of the home with support to communicating outside of the home alone. Training for friends and family may also need to be considered in order to facilitate optimal communication.129

Creating a meaningful role

Stroke survivors who described themselves as living successfully with a communication impairment advocated ‘doing things’ as being central to their success.52 62 Meaningful activity was something which was personal to the stroke survivor and varied across the studies identified. Meaningful activity could be as simple as completing chores around the house, establishing a routine or could relate to activities outside the home. The common theme was that the activity helped the stroke survivor to have a role which they valued, which they enjoyed or which gave them a sense of purpose.49 52 53 55 56 62 63 76

Sometimes stroke survivors struggled to participate in meaningful activities they had enjoyed prior to stroke due to their communication difficulties.54 60 61 69 71–73 75 However, those who described themselves as living successfully with a communication difficulty sought and took part in other activities which they were able to participate in and found pleasurable. The flexibility to adapt, adjust and take part in meaningful activity in spite of poststroke communication difficulties is significant. In these circumstances, the stroke survivor placed value on activities which they could participate in as opposed to those which they could not.49 52 53 55 56 62 63 76 Brown et al52 suggest that participating in meaningful activity is a process and describe participants’ experiences of finding a balance between the things they could still do and those they were no longer capable of.

I can’t read anymore … spelling is horrible since my stroke … I can’t do whatever I used to do. And I would—I feel that I’m useless … (But) I’m not depressed and … I laugh … And I am finding that I am living successfully with the stroke. Yes … I go for a walk. I ride the bike (indicates to exercise bike in lounge) … go out shopping with my wife. And go for an overseas trip. And I feel alright—yes.52(p. 1279)

This trial-and-error process may be important to create a meaningful role and to live successfully with poststroke communication difficulties.

One barrier to the creation of a meaningful role was the association between meaningful activity and communicative ability. Valued roles were often related to activities outside of the house, which stroke survivors found challenging to manage due to their communication difficulties. For example, a participant in Cruice et al54 describes his reliance on his wife for going out of the house:

(Communication) affected one man’s movements in his community (’C (wife) and I go to town often but I don’t go by myself…(aphasia) stops me going out…(it) depends on how people know you’)54 (p. 336).

This group also experienced other practical challenges common to many stroke survivors such as physical disability, fatigue or a lack of transport,60–63 72 which were additional barriers to participating in meaningful activity.

Future interventions should consider the role of meaningful activity in participants’ lives. Establishing a routine or scheduling activities which are valued by the stroke survivor may be key to living successfully with communication impairment. Intervention components to facilitate participation in meaningful activity may include supported activity-focused goal setting, action planning or problem solving.128 Problem-solving strategies or adaptations may be needed in order for the stroke survivor to participate in meaningful activity. This may take time and may involve trial-and-error process, particularly with regard to participation in activities which were valued prior to stroke and those occurring outside of the home environment.

Creating or maintaining a support network

Participants readily identified the importance of their family and friends for providing support on a practical and emotional level.51–55 58 61–64 70 72 76 As highlighted in the previous two analytical themes, it was often necessary for the stroke survivor to have some support from family or friends in order to complete activities outside of the home successfully. This support was highly valued and often enabled participants to manage activities outside of the home which might not otherwise have been possible. On the other hand, some stroke survivors discussed a lack of support, resulting in feelings of social isolation.51 52 56 61 69–72 75 76 In some circumstances, participants had friends prior to the stroke that had drifted away over time.51 56 75 Stroke survivors sensed that their old friends struggled to communicate with them in the same way and adapt to the new situation. Participants in the included studies described how initially friends had rallied round in the months after stroke but then gradually drifted away over time.51 56 75 Dalemans et al56 describe how friends seemed reluctant to get in contact with the person with communication difficulties. This suggests some level of discomfort in accepting or adapting to the stroke survivors problems with communication:

…Friends stayed away because they didn’t know how to handle the new situation. When time passed by, making contact became even more difficult… (p. 543).56

Future interventions should recognise the value of obtaining and maintaining social support. Stroke survivors with communication difficulties may be at risk of losing friends and having reduced social networks which may impact on quality of life and lead to social isolation. Social networks may be difficult to rebuild once lost given the communication challenges this subgroup of stroke survivors face. Some stroke survivors had identified communication groups as a means of social support and a way of replacing some of the friends they had lost.51–53 58 61 70 Stroke survivors expressed a sense of understanding from others in a similar position, which was not found through other friends or family members. A focus for future interventions may be to help stroke survivors with communication difficulties to find social support or sustain their existing social networks; where this is meaningful to the stroke survivor. Future interventions should acknowledge the role of social networks and explore how these might be harnessed to further support the stroke survivor and improve quality of life.130

Taking control and actively moving forward with life

As detailed in the descriptive themes, living with poststroke communication difficulties had resulted in tremendous change, which was often associated with loss for participants compared with prestroke life, for example, loss of communication, loss of self-identity, loss of friendship and loss of previously valued activities. For many stroke survivors, the sense of loss was, unsurprisingly, associated with significant emotional distress, triggering feelings of grief, loss and sadness.51 52 61 62 67 73 76 79 Many of these changes were beyond the stroke survivor’s control, however, in studies where stroke survivors described themselves as living successfully with the condition, a sense of taking control and actively moving forward was apparent.49 56 62 70 For example, one participant in Grohn et al62 stated:

But I want to improve myself, even if I wasn’t um like I am now and I was back to the way I was, I’d still push myself all the time. But they think that I’m pushing myself too hard sometimes (slight laugh). But I don’t think so. I just think I’ve got to learn to do these things and I think well I’m going to do it. (p. 1414)

This participant was highly motivated to improve; the authors of the paper state that the participant uses ‘improve’ in reference to both their communicative and physical abilities. Also apparent within this quote is the participant’s belief in their own ability to improve and how the participant ‘pushes’ to improve on the basis of this belief. A sense of taking control was also linked to independence. Participants in Brown et al52 valued tasks they could complete alone, for example, ordering a meal by themselves at a restaurant:

If you’re going out for dinner … make sure that you are … you do it. With yourself. (p. 1278)

A participant in Grohn et al63 describes how they perceived themselves to be living successfully with aphasia because they were able to do things independently:

…because I live on my own and that and I get up, I’m gone out of the place, and I get along-do everything myself and that. (p. 394)

Future interventions should be mindful of the significant loss and emotional upheaval associated with poststroke communication difficulties and recognise that stroke survivors may be at different stages of coming to terms with the changes to their lives. Different interventions may be appropriate according to the stroke survivors ‘readiness’ to accept their communication difficulties and move forward with rebuilding their lives.131 132 Participants’ beliefs in their own ability may also be related to the sense of taking control. Such experiences sit well with self-efficacy theory,133 which proposes that a person’s belief about his/her capabilities influences the ability to perform a task. Future interventions may wish to consider components which are targeted towards enhancing self-efficacy.

Discussion

The review identified 32 qualitative studies including 518 stroke survivors with communication difficulties from 9 different countries. Synthesising information from the qualitative literature has provided considerable insight into the longer-term needs of stroke survivors with communication difficulties living in the community. The synthesis reveals the ongoing difficulties stroke survivors can face in coming to terms with the loss of communication and in adapting to life with a communication difficulty. By drawing together findings reported in individual studies significant need for longer-term support was identified. Many of the participants who conveyed needs in relation to longer-term care were a number of years poststroke, which suggests that needs may persist over a significant period of time in the absence of resolution.

Our findings suggest that the biomedical model of illness is inadequate in understanding the full impact of communication disorders.134 Traditional speech and language therapy approaches are based on this model; typically focusing on treating the specific impairment the patient is experiencing.135 136 However, this synthesis of qualitative research demonstrates that the impact communication difficulties goes beyond symptoms of the medical impairment; influencing social relationships, mood and activities of daily living. The WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO ICF)137 recognises the complex interplay of biological, psychological and social influences which may influence health. Findings from the current review support this model and suggest that wider psychosocial factors should be considered in the rehabilitation of poststroke communication difficulties.116

Review findings also highlight the complex journey people with communication difficulties go though in adjusting and adapting to poststroke life. Some were able to come to terms with their communication difficulties, take control and rebuild their lives. Others struggled to adapt and were unable to overcome the loss of previously valued activities and roles. These findings are consistent with established theories of chronic illness such as the chronic illness trajectory proposed by Corbin and Strauss138 139 and Bury’s theory of biographical disruption,140 which explain how patients and families cope in different ways with their illness journey and the associated disruption to their lives. It is important to consider whether illness trajectories can be shaped so that stroke survivors with communication difficulties who struggle to adapt are better supported to manage their condition.

‘Self-management’ interventions are designed to support patients to cope with the physical and psychosocial consequences of living with a long-term condition.141 142 There is evidence to support the use of self-management interventions in a range of chronic conditions143–146 and there is a substantial policy drive towards taking this approach in stroke care.2 8 However, the evidence to support the efficacy of self-management approaches in stroke is mixed147 148 and a recent systematic review demonstrated that stroke survivors with aphasia are often excluded from RCTs of self-management interventions.148 A significant proportion of self-management interventions are based on or adapted from the Chronic Disease Self-Management programme145; a group-based patient education programme which has been assumed to be applicable across a range of chronic diseases. However, chronic diseases such as arthritis, diabetes and asthma may follow different trajectories to stroke.139 Stroke is sudden and life-threatening at onset and causes striking and immediate disruption to patients’ lives, in contrast to the more subtle onset and course of other chronic diseases. This suggests that self-management interventions may need to be designed specifically to meet the needs of stroke survivors (including those with communication difficulties) as opposed to being adapted from existing ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches.149

Existing self-management interventions have been criticised for their lack of user involvement and for being policy driven ‘top-down’ approaches as opposed to being driven by the needs and priorities of stakeholders.150–152 Although there is significant overlap with the experiences of the general stroke survivor population,24 40 44 findings from the current review highlight how poststroke communication difficulties present a unique barrier, for example, to participation in meaningful activities or maintenance of social networks. Although self-management may be a useful concept, the findings of the current review suggest that self-management interventions must be specifically designed to ensure they meet the needs of stroke survivors with communication difficulties and support them manage the psychosocial consequences of the communication difficulty itself. There is a paucity of research into the development and robust evaluation (RCTs) of psychosocial interventions for stroke survivors with communication difficulties. However, interest and research in this field is growing rapidly.153–156

Strengths and limitations of the review

A strength of the review is that we have used a systematic method to summarise and interpret existing qualitative research in relation to a specific research question. Although the themes stay close to the findings of the individual studies, by drawing the findings together we were able to create an overall interpretation of the literature in relation to longer-term need. Findings were drawn together in a systematic fashion and, based on the weight of this evidence, we were able to go beyond a descriptive summary of study findings by identifying the implications of the synthesis for understanding and responding to the longer-term needs of this group of stroke survivors and by making reasoned recommendations for future intervention development.

Two areas of limitation can be identified in this review. First, the quality of the synthesis is inherently limited by the quality and reporting of the original studies.32 157 The results of the quality assessment highlighted the lack of reflexivity in the included studies. Reflexivity is the researcher’s critical reflection on how their own position within the research may have influenced the conduct or findings of the study.158 159 The lack of reflexivity means it is difficult to evaluate levels of researcher bias in study findings. In the majority of studies, data were collected by researchers who were also qualified speech and language therapists. This may have had some influence on the line of questioning or participant’s responses or the analysis or presentation of results.

A second limitation is the difficulty assessing publication bias. It is possible there is a bias towards publishing studies highlighting difficulties poststroke as opposed to those highlighting more positive experiences. The current review identified significant need and this may be a result of biases in publication. It is difficult to quantify the impact of potential publication bias, however, it is important to note that studies were identified in the current synthesis which looked at patients who perceived themselves to be living successfully with aphasia and the factors influencing this.52 53 62–64 These studies were of high quality and made a significant contribution to the synthesis of information.

Implications for future research

Future research should explore the possible components of a longer-term care intervention for stroke survivors with communication difficulties and the feasibility of self-management as an approach. Few studies explored need within the first year poststroke and further information about how survivors with poststroke communication difficulties manage their condition following hospital discharge is required to further understand adaptation and adjustment during this time period and inform subsequent care strategies.

Conclusions

Our synthesis highlights the significant and continuing need for longer-term support experienced by stroke survivors with communication difficulties. Rehabilitation services designed around impairment-based models of speech therapy may fail to address the psychosocial consequences of poststroke communication difficulties and enable stroke survivors to successfully manage these difficulties within this context.160 Self-management interventions may be useful to facilitate the process of adaptation and adjustment, however, a critical examination of self-management approaches and their suitability for stroke survivors with communication difficulties is needed to ensure that such interventions meet the needs of this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jessica Hall and Farhat Mahmood for help with citation screening and double data extraction. The authors also thank Diedre Andre for help designing the search strategy, Tom Crocker for helpful suggestions on the first draft of the manuscript and Anne Forster for reviewing the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: FW contributed to the design of the study, acquired the data, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. DC contributed to the design of the study and reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding: This review was undertaken by the first author as part of a PhD project funded by the David and Anne-Marie Marsden scholarship for stroke rehabilitation (University of Leeds).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, et al. . Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990-2010: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2014;383:245–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61953-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health. National Stroke Strategy. 2007. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130105121530/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyandguidance/dh_081062 (accessed 13 September 2017).

- 3. McKevitt C, Fudge N, Redfern J, et al. . Self-reported long-term needs after stroke. Stroke 2011;42:1398–403. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cobley CS, Fisher RJ, Chouliara N, et al. . A qualitative study exploring patients' and carers' experiences of Early Supported Discharge services after stroke. Clin Rehabil 2013;27:750–7. 10.1177/0269215512474030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ellis-Hill C, Robison J, Wiles R, et al. . Going home to get on with life: patients and carers experiences of being discharged from hospital following a stroke. Disabil Rehabil 2009;31:61–72. 10.1080/09638280701775289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O’Connell B, Hanna B, Penney W, et al. . Recovery after stroke: a qualitative perspective. J Qual Clin Pract 2001;21:120–5. 10.1046/j.1440-1762.2001.00426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. NICE. Stroke rehabilitation in adults. 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg162 (accessed 13 September 2017).

- 8. Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party National clinical guideline for stroke. 5th edition London: Royal College of Physicians, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Forster A, Dickerson J, Young J, et al. . TRACS Trial Collaboration. A cluster randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of a structured training programme for caregivers of inpatients after stroke: the TRACS trial. Health Technol Assess 2013;17:1–216. 10.3310/hta17460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Forster A, Young J, Chapman K, et al. . Cluster randomized controlled trial: clinical and cost-effectiveness of a system of longer-term stroke care. Stroke 2015;46:2212–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Forster A, Young J, Green J, et al. . Structured re-assessment system at 6 months after a disabling stroke: a randomised controlled trial with resource use and cost study. Age Ageing 2009;38:afp095.:576–83. 10.1093/ageing/afp095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arboix A, Martí-Vilalta JL, García JH. Clinical study of 227 patients with lacunar infarcts. Stroke 1990;21:842–7. 10.1161/01.STR.21.6.842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Donkervoort M, Dekker J, van den Ende E, et al. . Prevalence of apraxia among patients with a first left hemisphere stroke in rehabilitation centres and nursing homes. Clin Rehabil 2000;14:130–6. 10.1191/026921500668935800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Engelter ST, Gostynski M, Papa S, et al. . Epidemiology of aphasia attributable to first ischemic stroke: incidence, severity, fluency, etiology, and thrombolysis. Stroke 2006;37:1379–84. 10.1161/01.STR.0000221815.64093.8c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Melo TP, Bogousslavsky J, van Melle G, et al. . Pure motor stroke: a reappraisal. Neurology 1992;42:789–95. 10.1212/WNL.42.4.789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Laska AC, Hellblom A, Murray V, et al. . Aphasia in acute stroke and relation to outcome. J Intern Med 2001;249:413–22. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00812.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hilari K. The impact of stroke: are people with aphasia different to those without? Disabil Rehabil 2011;33:211–8. 10.3109/09638288.2010.508829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hilari K, Needle JJ, Harrison KL. What are the important factors in health-related quality of life for people with aphasia? A systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:S86–S95.e4. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cruice M, Worrall L, Hickson L. Quantifying aphasic people’s social lives in the context of non‐aphasic peers. Aphasiology 2006;20:1210–25. 10.1080/02687030600790136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. MRC. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. 2008. www.mrc.ac.uk/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance/ (accessed 17July 2015).

- 21. NICE. Behaviour change: the principles for effective interventions. 2007. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph6 (accessed 14 September 2015).

- 22. NIHR. Patient and public involvement in health and social care research: A handbook for researchers. 2014. www.nihr.ac.uk/funding/./RDS-PPI-Handbook-2014-v8-FINAL.pdf (accessed 21 September 2015).

- 23. Salter K, Hellings C, Foley N, et al. . The experience of living with stroke: a qualitative meta-synthesis. J Rehabil Med 2008;40:595–602. 10.2340/16501977-0238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Satink T, Cup EH, Ilott I, et al. . Patients' views on the impact of stroke on their roles and self: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:1171–83. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walsh ME, Galvin R, Loughnane C, et al. . Factors associated with community reintegration in the first year after stroke: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:1599–608. 10.3109/09638288.2014.974834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dalemans R, Wade DT, van den Heuvel WJ, et al. . Facilitating the participation of people with aphasia in research: a description of strategies. Clin Rehabil 2009;23:948–59. 10.1177/0269215509337197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luck AM, Rose ML. Interviewing people with aphasia: Insights into method adjustments from a pilot study. Aphasiology 2007;21:208–24. 10.1080/02687030601065470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Simmons-Mackie N, Kagan A. Communication strategies used by’good’versus ’poor' speaking partners of individuals with aphasia. Aphasiology 1999;13(9-11):807–20. 10.1080/026870399401894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Simmons-Mackie N, Lynch KE. Qualitative research in aphasia: A review of the literature. Aphasiology 2013;27:1281–301. 10.1080/02687038.2013.818098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Attard MC, Lanyon L, Togher L, et al. . Consumer perspectives on community aphasia groups: a narrative literature review in the context of psychological well-being. Aphasiology 2015;29:983–1019. 10.1080/02687038.2015.1016888 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, et al. . Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy 2002;7:209–15. 10.1258/135581902320432732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, et al. . Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:671–84. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00064-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Evans D. Database searches for qualitative research. J Med Libr Assoc 2002;90:290–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Centre for reviews and dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. 2009. http://www.york.ac.uk/crd/SysRev/!SSL!/WebHelp/SysRev3.htm (accessed 17 July 2015).

- 36. Flemming K, Briggs M. Electronic searching to locate qualitative research: evaluation of three strategies. J Adv Nurs 2007;57:95–100. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04083.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shaw RL, Booth A, Sutton AJ, et al. . Finding qualitative research: an evaluation of search strategies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2004;4:5 10.1186/1471-2288-4-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J. An introduction to systematic reviews. London: Sage, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wong SS, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB, et al. . Hedges Team. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically relevant qualitative studies in MEDLINE. Stud Health Technol Inform 2004;107(Pt 1):311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McKevitt C, Redfern J, Mold F, et al. . Qualitative studies of stroke: a systematic review. Stroke 2004;35:1499–505. 10.1161/01.STR.0000127532.64840.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. Br Med J 2000;320:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. NICE. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (third edition). 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/15-appendix-h-quality-appraisal-checklist-qualitative-studies (accessed 12 July 2016). [PubMed]

- 43. Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0. 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org (accessed 17 July 2015).

- 44. Walsh D, Downe S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs 2005;50:204–11. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:59 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eaves YD. A synthesis technique for grounded theory data analysis. J Adv Nurs 2001;35:654–63. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01897.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, et al. . The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ 2010;340:c112 10.1136/bmj.c112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baylor C, Burns M, Eadie T, et al. . A qualitative study of interference with communicative participation across communication disorders in adults. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2011;20:269–87. 10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0084) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brady MC, Clark AM, Dickson S, et al. . Dysarthria following stroke: the patient’s perspective on management and rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil 2011;25:935–52. 10.1177/0269215511405079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brady MC, Clark AM, Dickson S, et al. . The impact of stroke-related dysarthria on social participation and implications for rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2011;33:178–86. 10.3109/09638288.2010.517897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brown K, Davidson B, Worrall LE, et al. . "Making a good time": the role of friendship in living successfully with aphasia. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2013;15:165–75. 10.3109/17549507.2012.692814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Brown K, Worrall L, Davidson B, et al. . Snapshots of success: An insider perspective on living successfully with aphasia. Aphasiology 2010;24:1267–95. 10.1080/02687031003755429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brown K, Worrall L, Davidson B, et al. . Living successfully with aphasia: family members share their views. Top Stroke Rehabil 2011;18:536–48. 10.1310/tsr1805-536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cruice M, Hill R, Worrall L, et al. . Conceptualising quality of life for older people with aphasia. Aphasiology 2010;24:327–47. 10.1080/02687030802565849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cyr R. Resilience in aphasia: Perspectives of stroke survivors and their families. Canada: University of Alberta, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dalemans RJ, de Witte L, Wade D, et al. . Social participation through the eyes of people with aphasia. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2010;45:537–50. 10.3109/13682820903223633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Davidson B, Howe T, Worrall L, et al. . Social participation for older people with aphasia: the impact of communication disability on friendships. Top Stroke Rehabil 2008;15:325–40. 10.1310/tsr1504-325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Davidson B, Worrall L, Hickson L. Exploring the interactional dimension of social communication: A collective case study of older people with aphasia. Aphasiology 2008;22:235–57. 10.1080/02687030701268024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dickson S, Barbour RS, Brady M, et al. . Patients' experiences of disruptions associated with post-stroke dysarthria. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2008;43:135–53. 10.1080/13682820701862228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dietz A, Thiessen A, Griffith J, et al. . The renegotiation of social roles in chronic aphasia: Finding a voice through AAC. Aphasiology 2013;27:309–25. 10.1080/02687038.2012.725241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fotiadou D, Northcott S, Chatzidaki A, et al. . Aphasia blog talk: How does stroke and aphasia affect a person’s social relationships? Aphasiology 2014;28:1281–300. 10.1080/02687038.2014.928664 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Grohn B, Worrall L, Simmons-Mackie N, et al. . Living successfully with aphasia during the first year post-stroke: A longitudinal qualitative study. Aphasiology 2014;28:1405–25. 10.1080/02687038.2014.935118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Grohn B, Worrall LE, Simmons-Mackie N, et al. . The first 3-months post-stroke: what facilitates successfully living with aphasia? Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2012;14:390–400. 10.3109/17549507.2012.692813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hinckley JJ. Finding messages in bottles: living successfully with stroke and aphasia. Top Stroke Rehabil 2006;13:25–36. 10.1310/FLJ3-04DQ-MG8W-89EU [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Howe TJ, Worrall LE, Hickson LMH. Observing people with aphasia: environmental factors that influence their community participation. Aphasiology 2008;22:618–43. 10.1080/02687030701536024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Howe TJ, Worrall LE, Hickson LMH. Interviews with people with aphasia: Environmental factors that influence their community participation. Aphasiology 2008;22:1092–120. 10.1080/02687030701640941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Johansson MB, Carlsson M, Sonnander K. Communication difficulties and the use of communication strategies: from the perspective of individuals with aphasia. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2012;47:144–55. 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Le Dorze G, Brassard C, Larfeuil C, et al. . Auditory comprehension problems in aphasia from the perspective of aphasic persons and their families and friends. Disabil Rehabil 1996;18:550–8. 10.3109/09638289609166316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Le Dorze GL, Brassard C. A description of the consequences of aphasia on aphasic persons and their relatives and friends, based on the WHO model of chronic diseases. Aphasiology 1995;9:239–55. 10.1080/02687039508248198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Le Dorze G, Salois-Bellerose Émilie, Alepins M, et al. . A description of the personal and environmental determinants of participation several years post-stroke according to the views of people who have aphasia. Aphasiology 2014;28:421–39. 10.1080/02687038.2013.869305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Matos MAC, Jesus LMT, Cruice M. Consequences of stroke and aphasia according to the ICF domains: Views of Portuguese people with aphasia, family members and professionals. Aphasiology 2014;28:771–96. 10.1080/02687038.2014.906561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nätterlund S B. A new life with aphasia: everyday activities and social support. Scand J Occup Ther 2010;17:117–29. 10.3109/11038120902814416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Niemi T, Johansson U. The lived experience of engaging in everyday occupations in persons with mild to moderate aphasia. Disabil Rehabil 2013;35:1828–34. 10.3109/09638288.2012.759628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Parr S. Psychosocial aspects of aphasia: whose perspectives? Folia Phoniatr Logop 2001;53:266–88. 10.1159/000052681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Parr S. Living with severe aphasia: Tracking social exclusion. Aphasiology 2007;21:98–123. 10.1080/02687030600798337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pound C. An exploration of the friendship experiences of working-age adults with aphasia. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pringle J, Hendry C, McLafferty E, et al. . Stroke survivors with aphasia: personal experiences of coming home. Br J Community Nurs 2010;15:241–7. 10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.5.47950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Runne C. Self-Efficacy in People with Speech or Language Disorders: A Qualitative Study . [Google Scholar]

- 79. Worrall L, Sherratt S, Rogers P, et al. . What people with aphasia want: Their goals according to the ICF. Aphasiology 2011;25:309–22. 10.1080/02687038.2010.508530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]