Abstract

Objectives

Infant body mass index (BMI) peak has proven to be a useful indicator for predicting childhood obesity risk in American and European populations. However, it has not been assessed in China. We characterised infant BMI trajectories in a Chinese longitudinal cohort and evaluated whether BMI peak can predict overweight and obesity at age 2 years.

Methods

Serial measurements (n=6–12) of weight and length were taken from healthy term infants (n=2073) in a birth cohort established in urban Shanghai. Measurements were used to estimate BMI growth curves from birth to 13.5 months using a polynomial regression model. BMI peak characteristics, including age (in months) and magnitude (BMI, in kg/m2) at peak and prepeak velocities (in kg/m2/month), were estimated. The relationship between infant BMI peak and childhood BMI at age 2 years was examined using binary logistic analysis.

Results

Mean age at peak BMI was 7.61 months, with a magnitude of 18.33 kg/m2. Boys (n=1022) had a higher average peak BMI (18.60 vs 18.07 kg/m2, p<0.001) and earlier average achievement of peak value (7.54 vs 7.67 months, p<0.05) than girls (n=1051). With 1 kg/m2 increase in peak BMI and 1 month increase in peak time, the risk of overweight at age 2 years increased by 2.11 times (OR 3.11; 95% CI 2.64 to 3.66) and 35% (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.21 to 1.50), respectively. Similarly, higher BMI magnitude (OR 2.69; 95% CI 2.00 to 3.61) and later timing of infant BMI peak (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.68) were associated with an increased risk of childhood obesity at age 2 years.

Conclusions

We have shown that infant BMI peak is valuable for predicting early childhood overweight and obesity in urban Shanghai. Because this is the first Chinese community-based cohort study of this nature, future research is required to examine infant populations in other areas of China.

Keywords: body mass index, obesity, overweight, longitudinal study, infants

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The longitudinal cohort with careful repeated measurements of child growth parameters provided the opportunity to characterise infant body mass index (BMI) peak over the first year of life.

As we lacked data on parent’s BMI and pregnancy weight gain, we could not ascertain the influence of these on infant BMI peak and contribution to childhood overweight and obesity.

Selection bias may exist in our study because 14.1% of the infants that were measured did not complete the follow-up at 2 years of age.

Introduction

The worldwide overweight prevalence among children aged under 5 years has risen from 4.8% in 1990 to 6.1% in 2014.1 The current worldwide obesity epidemic is a serious public health crisis.1–5 In 2014, almost half (48%) of obese individuals lived in Asia.1 In urban areas of China, the prevalence of overweight increased from 5.3% in 2005 to 8.5% in 2010.6 Rapid weight gain in early infancy is related to the adult development of obesity and cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension and impaired glucose tolerance.7–11 Environmental and behavioural factors are believed to be key drivers of obesity because although obesity is genetically influenced, genetic changes cannot explain the rapid increase in the prevalence of obesity.12 Therapeutic interventions in adulthood have poor long-term effects and are not cost-effective, therefore, the introduction of primary preventive strategies during infancy may be more important to reduce the risk of being overweight and obese.13–15

Body mass index (BMI), a useful estimate of adiposity for children aged more than 2 years, correlates with future health outcomes.3 7 A modest reduction in BMI Z-score after 1 year of obesity intervention may improve several cardiovascular risk factors.16 In young children, waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) is not superior to BMI in estimating body fat percentage, nor is WHtR better correlated with cardiometabolic risk factors than BMI in overweight/obese children.17 One study in Singapore suggested that early BMI may have an important impact on later metabolic outcomes in Asian populations.18

Few studies have evaluated the associations between infant BMI trajectory and childhood overweight and obesity.12 19–21 Weight-for-length percentile curves are often used but do not account for the age-based changes that reflect different stages of infancy.19 BMI increases from birth and reaches a maximum called the ‘BMI peak’ around age 7–9 months old, and then decreases and reaches a nadir around age 4–6 years old before increasing once again.19–21 According to Silverwood et al, both age and magnitude of BMI peak were positively associated with later BMI Z-scores.20 Additionally, several studies have used statistical models of growth trajectories to estimate the magnitude and timing of infant BMI peak.18–27

Ancestry-specific differences in Infant BMI peak are found between African-American and European populations.19 However, to date there have been no studies performed in China to demonstrate the utility of infant BMI peak for predicting the risk of childhood overweight and obesity. In order to form comparisons with other populations, we referred to a BMI modelling set by a cohort study in Philadelphia, USA19 23 Using a community-based longitudinal data set of serial measurements of length and weight from birth to childhood in Shanghai, we aimed to estimate the BMI peak characteristics in order to study the association between the infant BMI peak and overweight and obesity at age 2 years.

Methods

Study participants

We obtained our community-based longitudinal cohort data from the Shanghai Jing’an district birth and health records. Shanghai has a population of 19 million, as of 2009, and is divided into 17 urban districts and one suburban district. Jing’an district is located at the city centre and has a population of 248 000, as of 2009. ‘Providing free of charge health examination to children aged 0–3 years’ was a project funded by the Shanghai government for Jing’an children born from September 2009 onwards. Community health centres in the Jing’an district provide routine well-child checks for infants and young children. A District Childcare Database for all health centres in this project was established and managed by the Jing’an Maternal and Child Health Care Center. For the Childcare Database, health centre nurses record children’s gender, gestational age, birth weight, feeding and sleeping behaviours and other information during the child health examination. All children were followed from the age of 1 month to 2 or 3 years old until they went to kindergarten.

For this study, we used data from the Childcare Database for all children who were born from 1 September 2009 to 1 September 2013 and received care at the Jing’an district health centres. Children were followed from birth, with data collected at 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months of age from all five communities in Jing’an district, representing 69.9% (7456/10674) of all children in this age range in Jing’an district. Roughly 30% of children moved from Jing’an district to other districts of Shanghai during the study period, which resulted in a loss of follow-up in these cases. We gained approval (IRB#2015–TYSQ–03–11) for the current study from the Medical Research Ethics Committee, School of Public Health, Fudan University.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

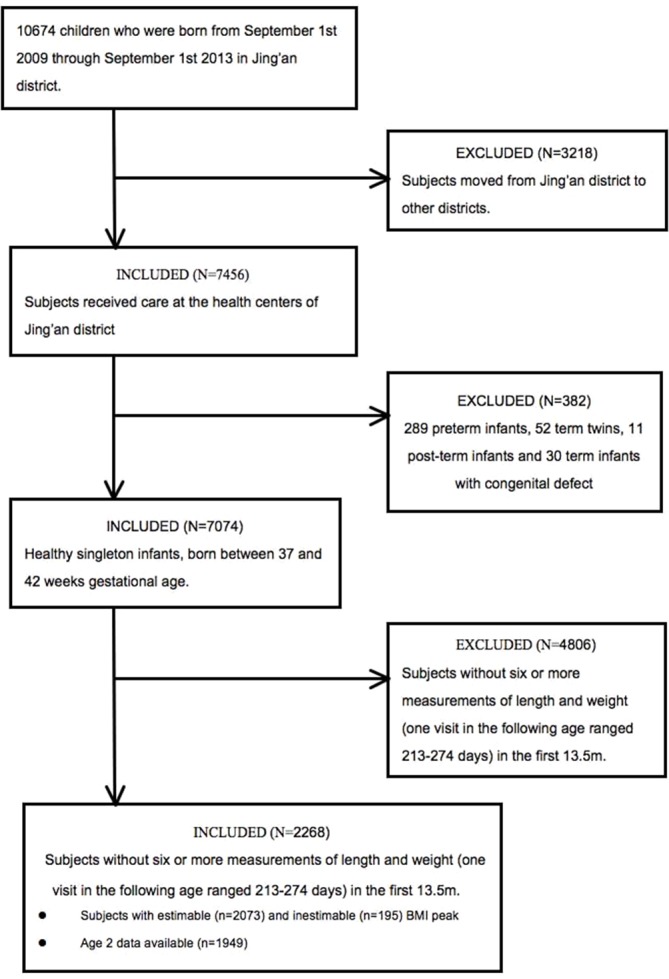

Inclusion criteria for the infants in this study specified healthy single births, a gestational age between 37 and 42 weeks and no physical problems. Participants were included if they had at least six measurements of length and weight in the first 13.5 months of life. The number and range of measurements were determined by the BMI modelling set by a cohort study in Philadelphia, USA.19 23 Because the BMI peak occurs around 7–9 months old, we included children who had at least one health examination visit between 213 and 274 days old. To test the relationship between infant BMI peak and childhood overweight and obesity, we included measurements for children at 2 years old when the data were available. Preterm infants (n=289), term twins (n=52), post-term infants (n=11) and term infants with congenital defects (n=30) were excluded. These children have different curve characteristics than normal term children.28 We used exclusion criteria similar to the Philadelphia cohort study to compare peak BMI with other populations.19 There were 21.2% (2268/7456) infants eligible for analysis. Of these, we observed 85.9% (1949/2268) children from birth to age 2 years, that is, until 1 September 2015 (figure 1). To assess potential selection bias, we compared demographics and birth characteristics of the analytic sample (n=2268) to the excluded healthy singleton infants (n=4806). There were no substantial differences in sex, birth weight, maternal age or overweight and obese rates at age 2 years of the two samples (online supplemental table 1).

Figure 1.

Recruitment flow chart and study sample. BMI, body mass index.

bmjopen-2016-015122supp001.pdf (402.7KB, pdf)

Anthropometric measures

Weight and length of children were measured by the same type of instruments at the community health centres. Weight for infants (0–18 months) was measured by an electronic paediatric scale (SECA 376 Weighing Scale) to the nearest 0.005 kg. Weight for toddlers (19–24 months) was measured by another type of scale (SECA 704 c Weighing Scale) to the nearest 0.05 kg. Recumbent length was measured from the top of the head to soles of feet using an infant mat (SECA 416 Mobile Measuring Mat) to the nearest 0.1 cm. BMI Z-score (BAZ) of children at age 2 years were calculated according to the 2006 WHO Child Growth Standards using WHO Anthro 2009 software.29 WHO Child Growth Standards was based on a multicountry study involving breast-fed children from six geographically distinct sites.1 Overweight was defined as BAZ >+1 (BMI >85th percentile) while obesity was defined as BAZ >+2 (BMI >97th percentile). Normal weight was defined as −1≤BAZ ≤ +1.2 13 Based on reports from previous studies,11 12 19 21 we extracted factors associated with childhood overweight from the electronic medical records. These factors were birth weight, sex, delivery mode, maternal age, duration of breast feeding and sleeping data. Parents answered to feeding and sleeping questions in follow-ups. They reported the age in months at which breast feeding was stopped. Sleep duration in hours was recorded at age 2 years. Because this cohort was set up after birth, some information about pregnancy and parents information was not available.

BMI trajectory modelling

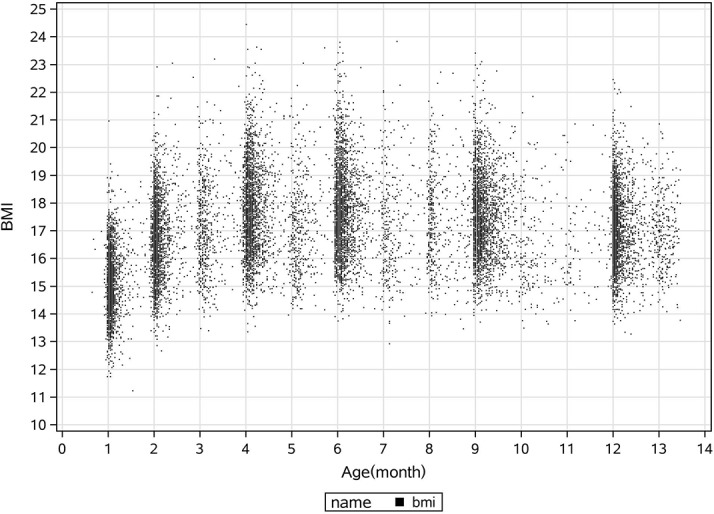

BMI peak was identified from subject-specific BMI growth curves established by serial BMI measurements (figure 2). A polynomial regression model with quadratic terms was fit to the BMI measurements over time. Regression modelling was used for each child to fit the following equation:19

Figure 2.

Plot of body mass index (BMI) data by age from birth to 13.5 months.

The first inflection point occurred at less than 408 days as derived from the equation and this was identified as BMI peak. The magnitude and timing of BMI peak were found by taking derivatives as follows:

Thus,

is the timing of BMI peak and is the magnitude of BMI peak.

The prepeak velocity was calculated using the following equation, with BMI at 14 days of age as the baseline measurement to avoid the period of neonatal weight loss seen in the first 2 weeks of life:21

The subjects who had a BMI peak within 14–408 days of life were defined as estimable (‘fit’) BMI trajectories, while those who were not identifiable by the model were called inestimable (‘not fit’) BMI trajectories.19

Statistical analysis

SPSS V.20.0 statistical software was used for all analyses and metalab 2014b for the BMI trajectory modelling. Data were presented as mean with 95% CI. Categorical data were summarised by calculating percentages. The X2 test and two-sampled t-tests were used to examine the differences between participants whose BMI trajectories were estimable or inestimable for the quadratic regression model and those who did or did not have measurements at age 2 years. We classified birth weight as the following categories: 1.5 to less than 2.5 kg, 2.5 to less than 4 kg and equal to or greater than 4 kg in the X2 test (table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics by subjects with ‘estimable’† and ‘inestimable’‡ BMI peak

| Characteristics | n | Estimable†, n (%) | Inestimable‡, n (%) |

| Total number | 2268 | 2073 | 195 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1126 | 1022 (49.3) | 104 (53.3) |

| Female | 1142 | 1051 (50.7) | 91 (46.7) |

| Birth weight | |||

| 1.5 to <2.5 kg | 35 | 30 (1.4) | 5 (2.6) |

| 2.5 to <4.0 kg | 2073 | 1905 (91.9) | 168 (86.2) |

| ≥4 kg | 160 | 138 (6.7)* | 22 (11.3) |

| Delivery mode | |||

| Vaginal birth | 1086 | 989 (47.7) | 97 (49.7) |

| Caesarean section | 1182 | 1084 (52.3) | 98 (50.3) |

| Maternal age | |||

| >35 years | 176 | 159 (7.7) | 17 (8.7) |

| ≤35 years | 2092 | 1914 (92.3) | 178 (91.3) |

| Total number with data at age 2 years | 1949 | 1790 (86.3) | 159 (81.5) |

| Total number of overweight and obese at age 2 years | 332 | 313 (17.5) | 19 (11.9) |

| Total number of obese at age 2 years | 44 | 43 (2.4) | 1 (0.6) |

χ2 tests were used to examine the differences between estimable and inestimable groups.

*p<0.05.

†Estimable: fit and identifiable BMI peak within 14–408 days of life.

‡Inestimable: not fit and identifiable.

BMI, body mass index.

To evaluate the associations between covariates and infant BMI peak characteristics and childhood BMI Z-scores, bivariate analyses were used by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni adjustments (table 2). BMI peak characteristics (age (in months) and magnitude (BMI; in kg/m2) at peak and prepeak velocities (kg/m2/month)) were estimated. The correlations between the estimated BMI peak characteristics were assessed by Pearson correlation analysis (online supplemental table 2). Logistic regression was used to assess the associations between BMI peak characteristics and childhood overweight (BAZ >+1) or obesity (BAZ >+2), adjusting for other background characteristics. Gender, delivery mode and maternal ages were defined as categorical variables. Birth weight, duration of breast feeding and sleeping were defined as continuous variable. We derived birth weight-for-gestational-age Z-scores using references from international standards for newborn30 (table 3). The coefficient of determination denoted R2 was used to describe the fit of every subject-specific curve. Statistical analyses were performed using only the subjects with estimable BMI peak.19–22 All statistical tests were two-tailed and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 2.

Infant characteristics in relation to infant BMI peak trajectories

| Magnitude (kg/m2), mean (95% CI) | Age (months), mean (95% CI) |

Prepeak velocities (kg/m2/month) mean (95% CI) |

|

| Total (n=2073) | 18.33 (18.26 to 18.39) | 7.61 (7.55 to 7.67) | 0.43 (0.42 to 0.44) |

| Gender | |||

| Male (n=1022) | 18.60 (18.21 to 18.69)*** | 7.54 (7.46 to 7.63)* | 0.42 (0.41 to 0.43) |

| Female (n=1051) | 18.07 (17.98 to 18.16) | 7.67 (7.59 to 7.76) | 0.43 (0.42 to 0.44) |

| Birth weight | |||

| 1.5 to <2.5 kg (n=30) | 17.63 (17.13 to 18.13) | 8.13 (7.56 to 8.70) | 0.44 (0.35 to 0.53) |

| 2.5 to <4.0 kg (n=1905) | 18.27 (18.21 to 18.34) | 7.63 (7.57 to 7.70) | 0.43 (0.42 to 0.44) |

| ≥4 kg (n=138) | 19.25 (18.97 to 19.52)* | 7.11 (6.88 to 7.34)*** | 0.39 (0.35 to 0.42) |

| Delivery mode | |||

| Vaginal birth (n=989) | 18.24 (18.14 to 18.34) | 7.64 (7.56 to 7.73) | 0.43 (0.42 to 0.44) |

| Caesarean section (n=1084) | 18.41 (18.32 to 18.50)*** | 7.58 (7.49 to 7.66) | 0.43 (0.42 to 0.44) |

| Maternal age | |||

| >35 years (n=159) | 18.42 (18.18 to 18.66) | 7.61 (7.49 to 7.82) | 0.44 (0.41 to 0.48) |

| ≤35 years (n=1914) | 18.32 (18.25 to 18.39) | 7.61 (7.55 to 7.67) | 0.42 (0.41 to 0.43) |

The analysis includes only infants who had BMI peak within 0–408 days and whose BMI trajectories were estimable by the quadratic model.

Bivariate comparison was performed using one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test.

*p<0.05; ***p<0.001.

BMI, body mass index.

Table 3.

Association between BMI peak characteristics and overweight and obesity at age 2 years

| Overweight at 2 years (n=1790) | Obesity at 2 years (n=1790) | |||

| Model containing infant BMI trajectory characteristics alone OR (95% CI) |

Initial model plus all independent variables OR (95% CI) |

Model containing infant BMI trajectory characteristics alone OR (95% CI) |

Initial model plus all independent variables OR (95% CI) |

|

| Magnitude (kg/m2) | 2.94 (2.54 to 3.40)*** | 3.11 (2.64 to 3.66)*** | 2.76 (2.11 to 3.60)*** | 2.69 (2.00 to 3.61)*** |

| Age (months) | 1.36 (1.23 to 1.51)*** | 1.35 (1.21 to 1.50)*** | 1.33 (1.08 to 1.65)** | 1.35 (1.08 to 1.68)** |

| Prepeak velocities (kg/m2/month) | 0.17 (0.07 to 0.40)*** | 0.14 (0.06 to 0.34)*** | 0.10 (0.02 to 0.56)** | 0.12 (0.02 to 0.74)* |

| Male (vs female) | 0.67 (0.49 to 0.90)** | 0.99 (0.51 to 1.96) | ||

| Birth weight Z-score,(continuous) | 1.06 (0.89 to 1.26) | 1.24 (0.84 to 1.82) | ||

| Duration of breast feeding (continuous) | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) | 0.92 (0.84 to 1.01) | ||

| Duration of sleep (continuous) | 0.89 (0.77 to 1.02) | 0.89 (0.63 to 1.24) | ||

| Caesarean section (vs vaginal birth) | 1.08 (0.81 to 1.44) | 0.80 (0.42 to 1.54) | ||

| Mother age (>35 years vs ≤35 years) | 0.68 (0.38 to 1.21) | 0.74 (0.21 to 2.59) | ||

The analysis includes only infants who had BMI peak within 0–408 days and whose BMI trajectories were estimable by the quadratic model.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

BMI, body mass index.

Results

Description of the study population

The demographic characteristics of the study population are presented in table 1. There were 2268 infants eligible for analysis, 49.6% men and 50.4% women. Most had a normal birth weight of 2.5 to less than 4 kg (n=2073, 91.4%). Eighty-five per cent (n=1949) of infants had follow-up data at least through the age of 2 years (table 1). Evaluated by the WHO Child Growth Standards, 17.0% (n=332) infants were overweight (BAZ >+1) and 2.3% (n=44) obese (BAZ >+2) at age 2 years.

Results of infant BMI trajectory modelling

Individual BMI trajectories were estimable using the polynomial regression model for 91.4% of the sample, with reasonable fit (mean R2=0.70±0.23). Mean magnitude of BMI peak was 18.33 (95% CI 18.26 to 18.39) kg/m2 and occurred at 7.61 (95% CI 7.55 to 7.67) months (online supplemental figure 1). Those subjects with inestimable BMI peak mostly showed either a BMI peak after 408 days of life or a decrease in BMI after birth. The prevalence of macrosomia (birth weight >4 kg) infants with inestimable infancy BMI peak were higher than that with estimable ones (6.7% vs 11.3%, p=0.024). Heavier macrosomia infants reached their BMI peak much earlier than other infants, since some of them attained BMI peak measurements just after birth. There was no significant difference in other factors between subjects with estimable and inestimable peak BMI (p>0.05)(table 1).

Participants’ characteristics in relation to infant BMI trajectories

Infant BMI trajectories were related to both sex and birth weight (table 2). The magnitude of BMI peak was greater, and timing of peak BMI was earlier, in boys than in girls and in children of higher birth weight than those of lower birth weight. There was no statistically significant difference in prepeak velocities with regard to infant characteristics.

General characteristics of children at age 2 years

We tested for differences between infants who had BMI data with estimable BMI peak at age 2 years (n=1790) versus those who did not (n=159). There was no statistical difference between the two groups in sex, birth weight, maternal age, duration of breast feeding, duration of sleep and overweight rates at age 2 years (p>0.05).

Association between infant BMI peak and childhood overweight and obesity

Table 3 shows the results of the association between BMI peak and risk of overweight and obesity at 2 years of age. When only the infant BMI peak was included in the model, higher magnitude and later timing of infant BMI peak increased the risk of overweight at 2 years. Furthermore, after adjustment for other infant background factors, higher magnitude (OR 3.11; 95% CI 2.64 to 3.66) and later timing (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.21 to 1.50) of infant BMI peak each increased the risk of overweight at 2 years. The results were also similar with regards to childhood obesity (table 3).

Discussion

Using a longitudinal set from a community-based cohort, we have demonstrated in the current analysis that infant BMI peak is useful for predicting childhood overweight and obesity in urban China. Boys had a higher average BMI peak and earlier average timing to achieve peak BMI than girls. Principally, our results show that higher BMI magnitude and later timing of infant BMI peak were each associated with increased risk of early childhood overweight and obesity.

This is the first community-based cohort study in China to characterise infant BMI peak and evaluate its association with risk of being overweight and obesity in early childhood. There have been remarkable increases in overweight and obesity in both rural and urban areas of China.31 Our findings can therefore be generalised to similarly aged children in Shanghai city and, to some degree, be extended to other areas in China. The longitudinal nature of the cohort data and the repeated measurements of length and weight parameters provided us with the opportunity to carefully model infant BMI trajectories of infants over the course of the first year of life. A limitation of our investigation was that only about 69.9% (7456/10 674) of all children in this age range had health records that only 85.9% of eligible children had complete follow-up data up to 2 years of age. Because children with incomplete data were excluded from the analysis, the risk of selection bias cannot be totally ruled out. Another weakness of the study is that the data concerning parent’s BMI, pregnancy weight gain, gestational diabetes mellitus and income were not available, because the cohort was defined after birth and not prenatally. Additionally, the reliability of the anthropometric measurements could not be ascertained due to the retrospective nature of the cohort. We acknowledge that the generated from routinely collected data may potentially influence the generalisability of the findings. Finally, the recorded BMI peak is estimation and not the true peak. Use of estimated BMI peak is potentially related to uncertainty in subsequent regression models.18

Few studies have investigated the utility of infant BMI peak in predicting childhood overweight and obesity.19–21 Principally, we found that higher BMI magnitude and later timing of infant BMI peak were each associated with increased risk of early childhood overweight and obesity. This result is similar to previous research from the cohort study conducted in USA19 and the Uppsala Family Study in Europe.20 However, some of our findings are not consistent with previous research. A 2010 prospective cohort study showed that more rapid increases in weight for length in the first 6 months of life were associated with a sharp increase in childhood obesity risk.32 Although most previous studies used weight or BMI at study-dependent fixed ages,32 33 our work was based on longitudinal and repeated measures of length and weight. Our results also demonstrate the differences in sex and birth weight were associated with BMI magnitude and timing of the BMI peak, but not with prepeak velocity.19 21 In recent studies, later timing of the BMI peak was observed in both girls and boys (8–9 months of age) from European or American populations.20 21 23 Girls peaked slightly later than boys in both populations. However, one recent study conducted in Singapore suggested that Asian children peak earlier (6 months) than European or American children and that sex does not significantly influence age at BMI peak in Asian infants. Notably, that study used natural cubic splines, compared with our analysis that used a polynomial regression model. It is possible that the use of different modelling methods to derive BMI peak characteristics could account for the observed differences across populations.18 Also, the effect of breast feeding may also explain the different ages of BMI peak observed across genders and populations. Further research is needed to demonstrate the clinical relevance of these small differences in BMI peak across populations. Furthermore, a previous study found a positive association between an earlier and higher BMI peak and birth weight.19 20 In our study, higher birth weight was not associated with a lower velocity, which was found by the Philadelphia cohort study.19

There is no widely accepted method to model infant BMI peak, appropriate peak age range and the number and timing of serial measurements.23 China is undergoing rapid social and economic developments, which is accompanied by an improvement in nutritional status. Current estimates indicate that overweight and obesity are rising in China, including in children.5 However, there has been a lack of studies evaluating the utility of BMI peak for predicting risk for being overweight or obese in later childhood in China, although BMI peak has been demonstrated to be ancestry-specific.19 Therefore, these findings can be used to help predict the early onset of obesity and to serve as a springboard for planning appropriate interventions to reduce the increasing trend of childhood overweightness and obesity in urban China. It is unclear why infants in our study had earlier BMI peaks (7–8 months) than infants from America and Europe (8–9 months),20 21 23 but it has been demonstrated that such differences may reflect ancestry-specific BMI peaks across populations.19 For this reason, cross-cultural investigations are required to determine the validity of this assertion. Understanding these differences may influence the design of public health intervention protocols to address childhood obesity.34–36

Conclusion

Using a community-based longitudinal cohort study with repeated measurements of infant growth parameters, we have for the first time determined that infant BMI peak is a useful metric to predict early childhood overweight and obesity in urban China. Our findings suggest that higher magnitude and later timing of infant BMI peak increased the risk of early childhood overweight and obesity. Infancy therefore represents a critical window of opportunity to prevent the emerging epidemic of overweight and obesity in children. Further studies from other urban populations in China are required in order to confirm or question our observations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff in Jing’an Maternal and Child Health Care Center for data extraction. We also acknowledge all children and their parents for participation.

Footnotes

Contributors: JS, BIN and ZW had the core idea for this study. All authors either analysed the data or interpreted the results. JS wrote the draft of the article. All other authors commented on the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China [71573049].

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standard. We gained approval (IRB#2015–TYSQ–03-11) for the current study from the Medical Research Ethics Committee, School of Public Health, Fudan University. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Commission presents its final report, calling for high-level action to address major health challenge. 2016. http://www.who.int/end-childhood-obesity/news/launch-final-report/en/

- 2. Benjamin Neelon SE, Schou Andersen C, Schmidt Morgen C, et al. . Early child care and obesity at 12 months of age in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Int J Obes 2015;39:33–8. 10.1038/ijo.2014.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, et al. . Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr 2007;150:12–17. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Skinner AC, Perrin EM, Skelton JA. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in US children, 1999-2014. Obesity 2016;24:1116–23. 10.1002/oby.21497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ji CY. Working Group on Obesity in China (WGOC). Report on childhood obesity in China (4) prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity in Chinese urban school-age children and adolescents, 1985-2000. Biomed Environ Sci 2007;20:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Commission. CNhaFP. National report on nutritional status of children aged 0-6 year. China: National health and Family Planning Commission, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andersen LG, Holst C, Michaelsen KF, et al. . Weight and weight gain during early infancy predict childhood obesity: a case-cohort study. Int J Obes 2012;36:1306–11. 10.1038/ijo.2012.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baird J, Fisher D, Lucas P, et al. . Being big or growing fast: systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. BMJ 2005;331:929 10.1136/bmj.38586.411273.E0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leunissen RW, Kerkhof GF, Stijnen T, et al. . Timing and tempo of first-year rapid growth in relation to cardiovascular and metabolic risk profile in early adulthood. JAMA 2009;301:2234–42. 10.1001/jama.2009.761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Monteiro PO, Victora CG. Rapid growth in infancy and childhood and obesity in later life--a systematic review. Obes Rev 2005;6:143–54. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00183.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:1019–26. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guo Y. Growth level of urban Chinese infants from birth to 2 years,body mass index Z scores' predicting model and its age trajectory in relation to maternal pre-pregnancy body weight status, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma JQ, Zhou LL, Hu YQ, et al. . Association between feeding practices and weight status in young children. BMC Pediatr 2015;15:97 10.1186/s12887-015-0418-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA, Levy D, et al. . Changing the future of obesity: science, policy, and action. Lancet 2011;378:838–47. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60815-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robinson SM, Crozier SR, Harvey NC, et al. . Modifiable early-life risk factors for childhood adiposity and overweight: an analysis of their combined impact and potential for prevention. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101:368–75. 10.3945/ajcn.114.094268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kolsgaard ML, Joner G, Brunborg C, et al. . Reduction in BMI z-score and improvement in cardiometabolic risk factors in obese children and adolescents. The Oslo adiposity intervention study - a hospital/public health nurse combined treatment. BMC Pediatr 2011;11:47 10.1186/1471-2431-11-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sijtsma A, Bocca G, L’abée C, et al. . Waist-to-height ratio, waist circumference and BMI as indicators of percentage fat mass and cardiometabolic risk factors in children aged 3-7 years. Clin Nutr 2014;33:311–5. 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aris IM, Bernard JY, Chen L-W, et al. . Infant body mass index peak and early childhood cardio-metabolic risk markers in a multi-ethnic Asian birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2016:dyw232 10.1093/ije/dyw232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roy SM, Chesi A, Mentch F, et al. . Body mass index (BMI) trajectories in infancy differ by population ancestry and may presage disparities in early childhood obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:1551–60. 10.1210/jc.2014-4028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Silverwood RJ, De Stavola BL, Cole TJ, et al. . BMI peak in infancy as a predictor for later BMI in the Uppsala family study. Int J Obes 2009;33:929–37. 10.1038/ijo.2009.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jensen SM, Ritz C, Ejlerskov KT, et al. . Infant BMI peak, breastfeeding, and body composition at age 3 y. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101:319–25. 10.3945/ajcn.114.092957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height, and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wen X, Kleinman K, Gillman MW, et al. . Childhood body mass index trajectories: modeling, characterizing, pairwise correlations and socio-demographic predictors of trajectory characteristics. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:38 10.1186/1471-2288-12-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chivers P, Hands B, Parker H, et al. . Body mass index, adiposity rebound and early feeding in a longitudinal cohort (Raine study). Int J Obes 2010;34:1169–76. 10.1038/ijo.2010.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson W, Choh AC, Lee M, et al. . Characterization of the infant BMI peak: sex differences, birth year cohort effects, association with concurrent adiposity, and heritability. Am J Hum Biol 2013;25:378–88. 10.1002/ajhb.22385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giles LC, Whitrow MJ, Davies MJ, et al. . Growth trajectories in early childhood, their relationship with antenatal and postnatal factors, and development of obesity by age 9 years: results from an Australian birth cohort study. Int J Obes 2015;39:1049–56. 10.1038/ijo.2015.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sovio U, Kaakinen M, Tzoulaki I, et al. . How do changes in body mass index in infancy and childhood associate with cardiometabolic profile in adulthood? findings from the Northern Finland birth cohort 1966 study. Int J Obes 2014;38:53–9. 10.1038/ijo.2013.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fenton TR, Nasser R, Eliasziw M, et al. . Validating the weight gain of preterm infants between the reference growth curve of the fetus and the term infant. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:92 10.1186/1471-2431-13-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. WHO. Anthro for personal computers, version 3. Software for assessing growth and development of the world’s children. Geneva: WHO, 2009. http://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 30. Villar J, Cheikh Ismail L, Victora CG, et al. . International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: the newborn cross-sectional study of the INTERGROWTH-21st project. Lancet 2014;384:857–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60932-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang YX, Wang SR. Rural-urban comparison in prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescents in Shandong, China. Ann Hum Biol 2013;40:294–7. 10.3109/03014460.2013.772654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Belfort MB, et al. . Weight status in the first 6 months of life and obesity at 3 years of age. Pediatrics 2009;123:1177–83. 10.1542/peds.2008-1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guo B, Mei H, Yang S, et al. . [Prenatal factors associated with high BMI status of infants and toddlers]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2014;52:464–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman K, et al. . Racial/ethnic differences in early-life risk factors for childhood obesity. Pediatrics 2010;125:686–95. 10.1542/peds.2009-2100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman KP, et al. . Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity: the role of early life risk factors. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:731–8. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zilanawala A, Davis-Kean P, Nazroo J, et al. . Race/ethnic disparities in early childhood BMI, obesity and overweight in the United Kingdom and United States. Int J Obes 2015;39:520–9. 10.1038/ijo.2014.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015122supp001.pdf (402.7KB, pdf)