Abstract

Introduction

Poorer health outcomes and disproportionate healthcare use in socioeconomically disadvantaged patients is well established. However, there is sparse literature on effective integrated care interventions that specifically target these high-risk individuals. The Integrated Community of Care (ICoC) is a novel care model that integrates hospital-based transitional care with health and social care in the community for high-risk individuals living in socially deprived communities. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the ICoC in reducing acute hospital use and investigate the implementation process and its effects on clinical outcomes using a mixed-methods participatory action research (PAR) approach.

Methods and analysis

This is a single-centre prospective, controlled, observational study performed in the SingHealth Regional Health System. A total of 250 eligible patients from an urbanised low-income community in Singapore will be enrolled during their index hospitalisation. Our PAR model combines two research components: quantitative and qualitative, at different phases of the intervention. Outcomes of acute hospital use and health-related quality of life are compared with controls, at 30 days and 1 year. The qualitative study aims at developing a more context-specific social ecological model of health behaviour. This model will identify how influences within one’s social environment: individual, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy factors affect people’s experiences and behaviours during care transitions from hospital to home. Knowledge on the operational aspects of ICoC will enrich our evidence-based strategies to understand the impact of the ICoC. The blending of qualitative and quantitative mixed methods recognises the dynamic implementation processes as well as the complex and evolving needs of community stakeholders in shaping outcomes.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was granted by the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB 2015/2277). The findings from this study will be disseminated by publications in peer-reviewed journals, scientific meetings and presentations to government policy-makers.

Trial registration number

Keywords: integrated care, community-based care, transitional care, low-income elderly community, participatory action research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Integrated Community of Care is a novel care model that integrates hospital-based transitional care with health and social care in the community for high-risk individuals living in socially deprived communities.

Study used a mixed-method participatory action research methodology to evaluate the effectiveness of a complex intervention programme for a high-risk urbanised low-income community.

A randomised controlled trial design is not possible for this study.

Introduction

Socioeconomically disadvantaged, socially isolated and elderly patients are at higher risk of ill health.1–4 Low socioeconomic status (SES) is well recognised as an independent risk factor for various adverse health outcomes, such as readmission risk3 5 6 and hospital use.7 In Singapore, public rental housing is an area-level measure of SES and is independently associated with increased readmission risk, frequent hospital admission and emergency department (ED) use.8 The reasons behind these poor outcomes include poor knowledge of personal health status, inappropriate health behaviours,9 inability to navigate the complicated healthcare system,6 10 lower health literacy and misalignment between patient and care team with regard to goals of care.11 These factors are common among residents of rental flats in Singapore. To qualify for heavily subsidised rental housing from the government, the gross household income must be SG$1500 or lower per month. The median household income in Singapore is SG$8290 per month.8 In these low SES communities, residents are known to have more comorbidity, poorer social support, more mental health disorders and depression.8 12 The confluences of these factors in a subpopulation of patients who tend to live together in socially deprived communities create challenges as well as opportunities to improve the health of the population.

While there is abundant literature highlighting the poorer health outcomes and disproportionate healthcare use in socioeconomically disadvantaged patients, there is sparse literature on integrated care interventions that specifically target these high-risk individuals. Englander et al13 described the Care Transitions Intervention (C-TraIn) programme, a nurse and pharmacist-led multicomponent transitional care (TC) programme conducted at an urban academic medical centre in Portland, Oregon. The C-TraIn programme included coaching and education, home visits for highest risk patients and provision of 30 days of medications for low-income adults who were uninsured or on public insurance. However, the intervention did not reduce 30-day readmission rates or ED reattendances. The authors concluded that the diverse needs of this population were too overwhelming for a nurse and pharmacist-based intervention. In Singapore, community-based initiatives led by social work professionals and paraprofessionals have been described.14 However, the programme faced similar problems and was hampered by the lack of a multidisciplinary healthcare team to address complex health and social needs across different settings of care. Three reviews on effectiveness of transitional care trials by Hansen,15 Kansagara16 and Kriplani17 independently concluded that transitional care interventions must be comprehensive, going beyond a single component intervention. Multicomponent interventions integrating medical and social care to span the different phases of care from hospitalisation, discharge planning to postdischarge surveillance is required to improve the health outcomes of such a high-risk community. The programme also need the flexibility to respond to individual needs. This current gap in caring for such high-risk communities is what our multicomponent intervention programme aims to address.

In Singapore, it is estimated that 900 000 citizens living in the city state will be 65 years or older by 2030 and at least 50 000 (5.3%) would be staying in rental housing.18 A shift from a hospital centric model of care to a community centric model of care is widely accepted as a strategy that will enable us to provide sustainable and cost-effective care for our rapidly ageing population. In response to this need, many new models of care were developed and tested for effectiveness. The Integrated Community of Care (ICoC) is a novel model developed by the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) that was designed to bring together best practices in transitional care19–22 in addition to a community virtual ward (VW) to coordinate community care and home-based primary care and a care closer to home (C2H) team for social case management and home help (fully elaborated under methods). In this care model, the ICoC fully integrates health and social care for high-risk individuals living in socially deprived communities. The ICoC programme is the first step to achieving optimal health in a high-risk population by systematically addressing biological, social and individual risk factors for poor health. Components of the ICoC programme will address social determinants of health such as social connectedness and loneliness; individual behaviours such patient activation, locus of control and environmental determinants such as access to health services and facilities.

The aim of this evaluation is to answer the following questions while providing feedback to key decision-makers over the 2 years of the project: (1) What is the overall effectiveness of the ICoC programme in improving acute hospital use? (2) What are the different components of the ICoC programme: their structure, their stakeholders (targeted patients and providers), their operating process and their effects on clinical outcomes? (3) What are the strengths and aspects to improve of each programme from the perspective of the concerned stakeholders in view of a better services integration? (4) What characteristics of the patients and the ICoC programme contribute to positive impacts on use of services, quality of life, patient activation and patient experience with care?

Methods/Design

Study site

Adopting a population health approach, the Ministry of Health Singapore has been advocating for the transformation of our healthcare system from a hospital centric to a community centric. In 2011, public healthcare delivery was reorganised into regional health systems (RHS). The aim of which was to organise regional health assets into an integrated structure that will promote care integration of care across the care continuum. There is to be vertical and horizontal integration of healthcare institutions. In addition, the regional health systems will work to integrate health and social care by working closely with social care agencies within each region. Six RHSs were created, each being responsible to integrate care for a specific geographic region in Singapore. Each RHS is anchored by a tertiary hospital, supported by a community hospital providing intermediate and rehabilitation care and complete with linkages to primary care and long-term care services in the region. In 2014, the Singapore Health Services (SingHealth) RHS was officially launched and consisted of primary to tertiary care institutions that account for the care of nearly a million residents in Singapore.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients are eligible if they are:

Aged ≥60 years at time of recruitment;

Staying in public rental housing in Chinatown area in Singapore.

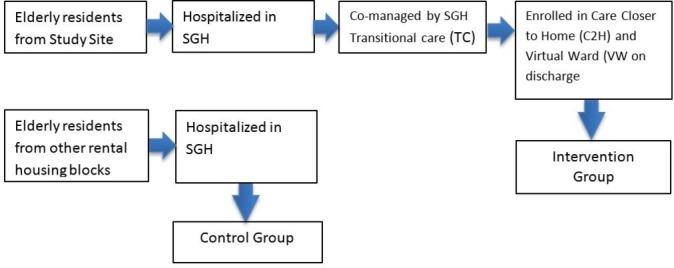

Chinatown was chosen as the C2H team had already started a social care case management and home help programme in this area since October 2014. We will exclude patients who decline our programme or dementia patients who are incapable of independent living and do not have a caregiver. Patients who have mild dementia and are capable of independent living or have a caregiver are suitable to be enrolled into the ICoC programme, which will support care in the community. Patients in the intervention group will be recruited during their first admission on study commencement (figure 1) on a consecutive sampling basis. Based on the electronic medical records, close to 180 unique patients were admitted to SGH in 2014. Assuming a low 5% rejection and exclusion rate (confirmed by our feasibility study), the recruitment period is estimated to be take 1.5 years (1 August 2016 to 31 January 2018). Recruitment will close when the sample size of 250 is reached. Control patients will be identified retrospectively at the end of the study period and data extracted from the SGH patient database using the index admission as the start date.

Figure 1.

Patient recruitment and comparison between intervention and control groups. SGH, Singapore General Hospital.

Intervention and control

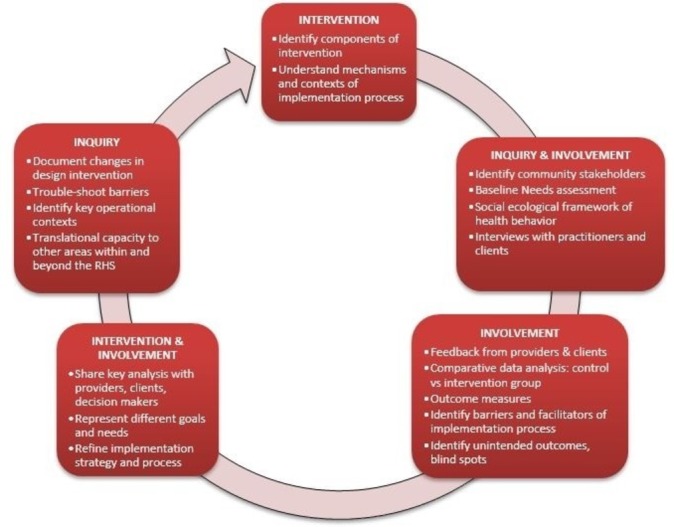

Components of the ICoC intervention programme (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of care for the ICoC programme. ICoC, Integrated Community of Care; SGH, Singapore General Hospital.

SGH TC team for care transitions of hospitalised residents

The SGH TC team (comprising a senior family physician and a medical officer) is a dedicated service that will provide inpatient care or comanagement with specialists for all enrolled patients, with emphasis on comprehensive discharge planning, formulation of a care plan postdischarge and proper hand-over care to the community VW and C2H teams. This intervention incorporates the best principles in transitional care that includes both predischarge and postdischarge component.16 22 The hand-over care will be executed via a daily half-hour video conferencing meeting between the three teams.

Community virtual ward for coordinating community care and home-based primary care

The community-based VW team comprises a staff nurse and resident physician seconded by SGH to provide continuing community care, home-based primary and nursing care to enrolled patients. This intervention is supported by strong evidence for home-based primary care and continuing care for frail elders.23 24 The team’s responsibilities include: (1) comprehensive geriatric assessment; (2) continuing care and at least weekly surveillance of discharged patients for up to 1 month postdischarge; (3) monitoring at risk patients for compliance to the prescribed care plans and medications; (4) health promotion and education to enrolled patients; (5) developing patient-specific action plans for patients with high risk diseases such as heart failure and diabetes and (6) coordinating and integrating the primary, transitional and social care for enrolled patients and (7) hand-over care to community service providers for long-term follow-up on stabilisation of patients and according to clinical protocol. The community VW team is physically located in the community.

C2H team for social case management and home help

Since October 2014, the C2H is a programme by the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) comprising a case manager, a social work assistant and five nursing aides to put in place health, personal and social services, for example, medication management, home help services to assist with basic activities of daily living for example, showering to help seniors to age in place. To date, the programme has enrolled close to 300 residents. AIC closely supports and provides professional guidance for the C2H programme.

All three components of the ICoC programme will be provided to enrolled patients. To ensure this, we have harmonised our inclusion and exclusion criteria for entry into all three components. The ICoC programme has been implemented since August 2016.

Control group participants

The control group of approximately 1100 participants from other rental housing blocks in our regional health system will receive current hospital standard of care when they are hospitalised. Patients will be managed by their specialists in charge depending on their admitting diagnoses. Patients may be referred to the SGH TC programme and/or various community services on discharge if deemed necessary by their specialists. Continuing care postdischarge may be provided at the specialist outpatient clinics or a primary care provider identified by the hospital specialist. The community VW and C2H teams will not be available for control group participants.

Conceptual framework for evaluation

The strategy of using multidisciplinary case management that we have adopted for our model of care has been widely used in many care integration programme aimed at reducing healthcare use and improve quality of care for frail older adults with multimorbidities.25 The evaluation of this model of care is challenging because it contains multiple components. For example, the medical, social and personal care components may act both independently of each other and interdependently in affecting the outcome of patient care. The assessment of individual components of intervention becomes complicated, creating the need for a novel adaptation of a mixed-method strategy of evaluation. Thus, our multidisciplinary research team combines the use of both quantitative and qualitative methods through a participatory action research (PAR) approach as part of the overall evaluation of the effectiveness of the ICoC programme.

PAR has been defined as ‘systematic inquiry, with the participation of those affected by the problem being studied, for the purposes of education and action or effecting social change’.26 In Singapore, the recent and rapid transformation of health services delivery for the ageing population had created unprecedented shifts in the power relationship between users, policy-makers and service providers in the healthcare system. PAR with community-dwelling socially-at-risk elderly Singaporeans has the potential to explore some of the complex health and social problems that poor and socially isolated elderly face while also contributing to individual and community capacity building. In the context of our research site, PAR is an appropriate process for evaluating patient-centred models of care, especially since the action research strategies that we are proposing are common to processes in the field of nursing—particularly through the steps of assessment, planning, implementation, evaluation and replanning.27 The ‘PIE method’, for instance, has been used among nurses to document patients’ progress, where its acronym stands for identifying problems, proposing interventions and evaluation.28 PAR has also been engaged successfully to facilitate improvements in healthcare services.29

A mixed-methods PAR approach will facilitate a more comprehensive assessment of the ICoC, particularly to understand the multiple outcomes of the programme in terms of what works, for what and for whom. In this regard, PAR is intended to be both highly localised and comparative. Investigation of the programme structure, its operating processes and stakeholders’ experiences can be captured through qualitative methods while the comparative assessment of health outcomes between the intervention and control group will be valuably complemented through quantitative research methods. Our preferred approach is driven by the learning objectives of investigators and by the circumstances and contexts of the community involved.

Research design

The ICoC study is a single-centre prospective, controlled, observational study performed in the SingHealth RHS.30 31 Drawing on established trends in PAR praxis which emphasises collective processes of investigation and involvement as well as experimentation grounded in experience and social history,32 33 our research design similarly includes a learning component. We have conceptualised our design in terms of a synergy between the three ‘Is’ of intervention (action), involvement (participation in the community) and inquiry (research) into a feedback cycle (figure 3). The three Is mutually augment each other to contribute to the social transformation of integrated elderly care. The approach requires the copartnership of stakeholders, implementation teams and research units to collect data, reflect on findings of outcomes and refine the intervention process further to develop and achieve better delivery and results of ICoC.

Figure 3.

Research design: intervention, involvement and inquiry feedback cycle.

The mixed-methods PAR approach to the ICoC model is significant to health systems research because it attempts to triangulate both medical providers’ and elderly patients’ perspectives of intervention delivery. In this regard, our research design intends to capture sensitivity to outcomes beyond only the intended hypothesis. Additionally, while evaluation studies use quantitative data to measure intervention outcomes, a qualitative approach may address the limitations of using a single metric of examining hospital admissions, which have been found to be less suitable for complex and vulnerable patients where many other factors contribute to the need for hospitalisation.34 35

Study aims and hypotheses

Our PAR model combines two research components, quantitative and qualitative, at different phases of the intervention. The primary objective of the quantitative study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the ICoC programme in achieving a significant reduction in the proportion of patients in the intervention group with acute hospital readmissions within 30 days of the index discharge date relative to controls. The index admission and index discharge dates are defined as the date of the patient’s first admission to the hospital and discharge from the hospital, respectively. The secondary aims of this study are to evaluate the effectiveness of the ICoC programme in achieving (a) a lower proportion of patients in the intervention group with three or more unscheduled hospital readmissions within 1 year of index discharge; (2) a lower ED attendance rate in the intervention group at 30 days and 1 year from index discharge; (3) a lower specialist outpatient clinic attendance rate in the intervention group at 30 days and 1 year from index discharge; (4) improving health-related quality of life in the intervention group relative to baseline as measured by the EuroQoL Five Dimension (EQ-5D) at 30 days and 1 year compared with the control group.

The qualitative study aims at developing a more context-specific social ecological model of health behaviour.36 We propose a social ecological framework of health behaviour in the manner below.

Care recipients’ and caregivers’ conditions and experiences (individual level);

Interactions between elderly patient, caregivers and healthcare providers (interpersonal level);

Elderly and caregiver’s access experiences with service use and healthcare delivery (institutional/organisational level);

Elderly patients’ connections with and support from the community (community level);

How public initiatives and access to other healthcare programmes affect the experience of transitional care postdischarge (policy level).

This model helps to identify how influences within one’s social environment: individual, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy factors affect people’s experiences, behaviours and clinical outcomes during care transitions from hospital to home. The knowledge of how this model operates on the ground will enrich our evidence-based strategies to understand the impact of the ICoC. The PAR operates on a feedback loop that is sensitive to changes experienced by providers and patients in real time. In this project, both the implementation and research team work in tandem to evaluate and improve the intervention once primary outcomes have been measured or unintended outcomes have been reported.

Sample size calculation

Data from a previous feasibility study shows a historical 30-day readmit rate of 17.5% for patients in the three proposed intervention blocks and 16.8% in the control blocks. The prospectively recruited sample size for the intervention will be 250 and, based on 2014 data, we anticipate about 1100 patients in the control group. The figure shows the proposed sample sizes will provide ≥80% power using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test (α=0.05) to detect the following range of differences (unadjusted) in 30-day readmit rates between control versus intervention: 18.0 versus 10.7; 17.0 versus 9.9; 16.0 versus 9.1; 15.0 versus 8.3; 14.0 versus 7.5 and 13.0 versus 6.7. Targeted reductions in intervention group readmission rates range from 40.5% to 48.5% and would certainly be considered clinically meaningful. In our previously published VW study,22 we achieved 33% reduction in 30-day readmission rates, and it is likely this can be improved with additional home visits and social care case management.

For the qualitative component, the research team will purposively select a sample of 40 elderly patients/clients based on the sample of 250 elderly residents who are enrolled in C2H intervention programme and who are also under the supervision of the VW. The elderly patients/clients are recruited into the study through referrals from medical and care team based on their health status and case severities (eg, polypharmacy, multiple comorbidities, frailty). Since the qualitative study will be conducted over a year, we derived the sample size (n=40) elderly clients based on feasibility in terms of time, recruitment and limited manpower resources. We projected our sample size based on the concept of information power, which indicates that the more information the sample holds that will be relevant for the actual study, the lower the number of participants needed.37 We appraised the information power of our sample based on the following factors:

Sample specificity: all qualitative participants are elderly clients enrolled in the ICoC and share specific similarities for example, in terms of poor SES, low literacy, living alone, mental impairment and difficulties in managing chronic illness. The variations that we intend to represent in our sample would be medical complexities, sex, race, caregiving arrangements and age (60–90 above).

Applying mixed use of deductive and inductive/grounded theory approaches necessitate that the sample needs to provide a solid foundation to ground conclusions.

Strong quality of dialogue: experienced research team conducting multiple in-depth interviews with each client will produce rich and meaningful data to evaluate the user perspective of the ICoC intervention.

Exploratory and thematic cross-case analysis will be conducted based on in-depth interview responses.

From the factors above, we are confident that our study can obtain sufficient information power with a sample size of 40, without compromising depth and rigour.

The research team will also be interview all community health providers (n=10) who are providing care in the study site.

Data collection strategies to measure outcomes

Basic characteristics

Intervention group

The research team will obtain informed consent from the intervention group participants and interview them for demographic, socioeconomic status, medical comorbidities, abbreviated mental test and modified Barthel Index, instrumental activities of daily living and health-related quality of life (EQ-5D). This information will allow the investigators to characterise and identify needs in our intervention group patients better.

Control group

Control group patients will be retrieved from the eHIntS system. The eHIntS system is SingHealth’s electronic health record system that integrates information from multiple sources including administrative data (for example, patient demographics), clinical data and ancillary data into our enterprise data warehouse. A waiver of patient consent will be sought from the centralised institutional review board for extraction of deidentified routinely collected information. Similar demographic, SES and medical comorbidities data (predictors used for propensity scores calculation listed in(Online supplementary appendix A) will be collected for both groups to allow calculation of propensity scores as a basis for comparability. We have shown in our previous study31 that these data can be extracted from our data warehouse for inclusion in a propensity score model. Information such as abbreviated mental test, modified Barthel index, instrumental activities of daily living and health related quality of life will not be available for the control group.

bmjopen-2017-017839supp001.pdf (168.1KB, pdf)

Outcome measures at 30 days and 1 year

The research team and the ICoC team will follow-up with study participants for the primary and secondary outcomes at 30 days and 1 year (table 1). An unscheduled readmission is defined as a readmission for a non-elective indication. Unscheduled readmission at 30 days (short-term outcome) is a universally accepted indicator of transitional care quality and 1 year outcomes (long-term outcome) is chosen to reflect the quality of community and continuing care. The research team will conduct a face-to-face survey interview at 30 days and 1 year to repeat the EQ-5D scales. Healthcare use data of intervention and control group participants will be extracted from SingHealth’s eHIntS system and merged with Ministry of Health (MOH)’s Omnibus data resource. The MOH’s Omnibus data resource contains national-level healthcare use data and will ensure complete and accurate healthcare use outcomes and overcome the issue of cross-use to different healthcare clusters in Singapore. Similarly, predictors of 30-day readmission that will be used for propensity score matching will be available from eHIntS and Omnibus databases.

Table 1.

Data collection sources at baseline, 30 days and 1 year outcomes for participants

| Variable | Method of collection | Baseline | Follow-up (30 days) | Follow-up (1 year) |

| Demographic, SES, health information and prior healthcare use, abbreviated mental test, modified Barthel Index, instrumental activities of daily living, health-related quality of life | Questionnaire, EQ-5D, eHIntS | X | ||

| Primary outcome measure—unscheduled hospital readmission within 30 days of index discharge | eHIntS, Omnibus | X | ||

| Secondary outcome measures— 1. Unscheduled hospital readmissions at 1 year 2. and 3. Emergency department attendances, specialist outpatient clinic attendances at 30 days and 1 year4. Health-related quality of life at 30 days and 1 year |

EQ-5D, eHIntS, Omnibus | X | X |

SES, socioeconomic status.

A checklist will be developed to measure fidelity to components of ICoC programme and ensure standardisation of intervention and the designed interventions are faithfully adhered to. The nature (routine/emergency) and number of home visits for example, doctor/nurse/C2H will be retrieved from the clinical documentation notes.

Qualitative data collection design and strategies

The qualitative research component of the PAR will be conducted in three phases.

Phase 1: Intervention and involvement

Understanding mechanisms and contexts of intervention (providers and patients)

The research team will engage in ‘go-along’ interviews with nurses and community healthcare providers to understand the complexities around integrated care in a low-income rental neighbourhood. The ‘go-along’ combines both participant observation and interview methods and will be conducted with all of the VW nurses and the C2H team (n=10) as they go about their daily care rounds around the study site. Data collected will provide information in terms of patient/clients’ receptivity to medical intervention, relationship between providers and their elderly patients/clients. The objective of go-along interviews is to capture the providers’ perspective of the barriers and facilitators in the implementation of ICoC to their patients/clients. Research team will document processes in which medical providers understand, implement and apply appropriate practices of care to the elderly residents in low-income rental dwelling. For triangulation, the research team will conduct content analysis of providers’ case summaries over the period of intervention to trace the chronology and outcome of individualised interventions.

Elderly residents’ qualitative needs assessment based on case summaries and complementary quantitative study

Based on case summaries by healthcare providers, research team will work with implementation team to identify and categorically group elderly residents based on complexity of case and specific health conditions. The medical team and nurses will refer 40 cases/elderly clients with different physical and health status as well as across gender, ethnicity, age and living arrangements to the research team for phase 2b of in-depth semistructured/informal interviews. Elderly residents will be grouped according to similarities in terms of case complexity (first strata) followed by whether they show improvements in health behaviour or not (second strata).

Phase 2: Action learning through involvement and inquiry

a. This phase involves interpreting preliminary data, explaining contexts, translating findings and refining identified problems, priorities and strengths together with key community members—clinicians, nurses, resident committee members and elderly residents who are physically and cognitively able to participate and be involved in discussions. Through focus group discussions, the aim of this phase is to: (1) to understand how providers define care and how their vision of care is being expressed through their practices and (2) to understand the background profile of clients and develop case-studies of ‘complex’ cases and how both the providers, resident committee and patients manage these issues.

ICoC user experience (n=40 based on referral in phase 1b)

Research team will establish rapport with elderly residents in intervention group and conduct in-depth interviews to explore the experiences and attitudes of older people who are in the intervention group (VW and C2H). Objective is to gain an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of community care from the perspective of recipients in the study site.

Once the Institutional Review Board (IRB) has given ethics approval to conduct the research, the investigators will invite residents in the intervention group to participate in research study through case referrals by nurses and community health providers. Due to the nature of the user experience research which requires substantial feedback from participants, nurses and community health providers will only refer elderly clients who are able to respond to questions without requiring a proxy. When comfort and trust has been established between the research team and participants, investigators will conduct interviews following a life history format. We will ask about their personal histories to gain a deeper and better understanding of their current circumstances and health behaviours. We will also seek their feedback as recipients of the care intervention. Interviews will be carried out over multiple sessions and visits, instead of a block session, so as to not tax elderly participants. Each session would last about approximately 30 min and will continue until all questions in the interview guide (see online supplemetary appendix B) have been satisfactorily completed.

bmjopen-2017-017839supp002.pdf (164.4KB, pdf)

Phase 3. Inquiry and intervention

Data analysis and findings from phases 1 and 2 will provide feedback on the delivery of the intervention. These findings will be analysed together with the post-30 days and post-1 year quantitative outcome measures to identify which mechanisms of the intervention have been successful and which require improvements. Improvements to the intervention will only be implemented and executed only after our primary outcomes have been collected and analysed. Additionally, the objective of phase three is to also highlight unintended negative consequences or beneficial outcomes of the intervention that clients and providers experience. The team will further analyse implications of findings and translational capacity to other low-income rental community-dwelling areas in Singapore.

Analysis

Quantitative data analysis

To analyse our primary aim (table 1), control and intervention 30-day readmission rates will be compared using logistic regression using propensity scores to adjust for effects of confounders.

The secondary aim one analysis (table 1) will use Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression and compare groups on proportions of patients with three or more unscheduled hospital readmissions within 1 year of index discharge. Secondary aims 2 and 3 (table 1) will involve Poisson regression analysis on numbers of emergency department and specialist outpatient clinic visits, respectively, per 3-month and 1-year intervals, and aim 4 (table 1) will involve standard analysis of variance methods to compare quality of life scores. All analyses will incorporate propensity score adjustment. All analyses will be performed using SAS V.9.4 software (SAS).

Qualitative data analysis

All in-depth interviews with key personnel and focus group discussions will be audiotaped and transcribed and uploaded onto qualitative software database nVivo V.11. While ‘go-along’ interviews with nurses and case workers and interviews with elderly recipients with speech difficulties (eg, slow speech, inaudible voice) will not be audiorecorded due to the anticipated long duration of such sessions and difficulty in capturing speech, respectively. Written notes will be used instead to record such observations and conversations and will be typewritten at the end of each day. Typewritten notes will also be uploaded onto NVivo 11. The research team will use NVivo to code responses for theoretical and emergent themes regarding practitioner and client/patient (provider–user) experience of the ICoC programme.

The team will analyse data, by coding for broad themes that correspond to influences at the individual, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy level according to the social ecological framework of health behaviour while simultaneously code for emergent themes. The combination of both deductive and inductive analytical approaches will provide further granularity for the evaluation of the ICoC intervention programme. Data will be independently coded by two qualitative analysts and codings will be compared for agreement through NVivo to achieve inter-rater reliability.

Ethics and dissemination

Informed consent for participation in the ICoC intervention programme will be taken from each enrolled patient. Participation in the study is voluntary and care services will not be withdrawn should elderly patients decide to not participate or withdraw from the study. After obtaining consent, the qualitative research team will build rapport of elderly participants further through regular interactions facilitated by frequent house visits with community nurses and health providers. Additional informed consent to participate in the research study will be taken for patients/clients who have been referred to research team and for providers and stakeholders who will be interviewed and/or participating in focus group discussions. SingHealth Centralised IRB (CIRB 2015/2277) and National University of Singapore IRB (NUS IRB: H-17–035) has approved this study.

Findings will be disseminated by publications in peer-reviewed journals, scientific meetings and presentations to policy-makers and practice providers.

Status of the study

The ICoC programme is expected to last 2 years, from July 2016 to June 2018.

Discussion

It is increasingly recognised that non-biological determinants of health such as social, environmental and individual behaviours impact significantly on health outcomes.38 39 These non-biological determinants of health interact in a complex relationship a person’s biological health determinants such as gender, age, inherited and acquired health conditions. Therefore, quality healthcare alone cannot achieve optimal outcomes in health. Policy changes and interventions (the ICoC programme in this case) that can modify health-seeking behaviour and affect delivery of healthcare services may in turn affect health determinants and health outcomes. Implementing a complex ICoC intervention programme and understanding the complex interaction between determinants, policy and outcomes therefore require an innovative approach to evaluation such as the PAR model.

The findings from ICoC programme will directly inform policy-makers on the feasibility of implementation and effectiveness of integrating traditional silos of practice on reducing acute hospital use. This has direct policy implications on the funding model and quantum to support such a programme. In the short to medium term, the study will develop a novel model of integrated care that shifts care from a hospital centric system to an integrated community centric system for high-risk communities. In the long term, the study has policy implications on the feasibility and effectiveness of empanelment of high-risk communities (assigning individuals to care teams) to a community-based integrated care team supported by the regional health system. The systematic inquiry, with the participation of those affected by the problem being studied, will enable the ICoC programme and policy-makers to understand the complex interaction between health determinants, intervention and health outcomes. This knowledge will facilitate design of better interventions and policies that systematically address health determinants and policies in future iterations of the ICoC programme.

Our study has potential limitations. First, a randomised controlled trial design would be most appropriate for evaluating the effectiveness, but it is not always the best design for process indicators. Moreover, we had wanted to evaluate the effectiveness of the synergism achieved by all three components of the ICoC programme. The restriction of the C2H programme to the three intervention blocks precluded us from randomising the rental housing blocks or patients for intervention. We will minimise bias in the statistical comparison of the intervention and control groups by using propensity scores to balance baseline covariates. Second, this study is limited to a single rental housing community, so generalisability to other rental housing communities would be unknown. If results from the ICoC programme are promising, we intend for this model of care to be propagated to other rental housing communities throughout RHS and Singapore.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the SingHealth Regional Health System Office, staff from the Singapore General Hospital Office of Integrated Care and Associate Professor Angelique Chan from Duke-NUS Medical School Centre for Ageing Research and Education for their support.

Footnotes

Contributors: LLL, AM and LKH conceived and designed the study. LLL and AM wrote the first draft of the paper, and all authors critically revised the paper and gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: SIng Health Centralized Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Low LL, Liu N, Ong MEH, et al. Performance of the LACE index to identify elderly patients at high risk for hospital readmission in Singapore. Medicine 2017;96:e6728 10.1097/MD.0000000000006728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Franchi C, Nobili A, Mari D, et al. Risk factors for hospital readmission of elderly patients. Eur J Intern Med 2013;24:45–51. 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hu J, Gonsahn MD, Nerenz DR. Socioeconomic status and readmissions: evidence from an urban teaching hospital. Health Aff 2014;33:778–85. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lim KK, Chan A. Association of loneliness and healthcare utilization among older adults in Singapore. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2017. 10.1111/ggi.12962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krumholz HM, Bernheim SM. Considering the role of socioeconomic status in hospital outcomes measures. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:833–4. 10.7326/M14-2308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arbaje AI, Wolff JL, Yu Q, et al. Postdischarge environmental and socioeconomic factors and the likelihood of early hospital readmission among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Gerontologist 2008;48:495–504. 10.1093/geront/48.4.495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Filc D, Davidovich N, Novack L, et al. Is socioeconomic status associated with utilization of health care services in a single-payer universal health care system? Int J Equity Health 2014;13:115 10.1186/s12939-014-0115-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Low LL, Wah W, Ng MJ, Win W, Mjm N, et al. Housing as a Social Determinant of Health in Singapore and Its Association with Readmission Risk and Increased Utilization of Hospital Services. Front Public Health 2016;4 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, et al. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff 2013;32:1196–203. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kangovi S, Levy K, Barg FK, et al. Perspectives of older adults of low socioeconomic status on the post-hospital transition. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2014;25:746–56. 10.1353/hpu.2014.0111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, et al. Challenges faced by patients with low socioeconomic status during the post-hospital transition. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:283–9. 10.1007/s11606-013-2571-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wee LE, Yong YZ, Chng MW, et al. Individual and area-level socioeconomic status and their association with depression amongst community-dwelling elderly in Singapore. Aging Ment Health 2014;18:628–41. 10.1080/13607863.2013.866632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Englander H, Michaels L, Chan B, et al. The care transitions innovation (C-TraIn) for socioeconomically disadvantaged adults: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1460–7. 10.1007/s11606-014-2903-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shum E, Lee CE. Population-based healthcare: the experience of a regional health system. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2014;43:564–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, et al. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:520–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kansagara D, Chiovaro JC, Kagen D, et al. So many options, where do we start? An overview of the care transitions literature. J Hosp Med 2016;11:221–30. 10.1002/jhm.2502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, et al. Reducing hospital readmission rates: current strategies and future directions. Annu Rev Med 2014;65:471–85. 10.1146/annurev-med-022613-090415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singapore DoS. Population trends. 2015. http://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/publications-and-papers/population-and-population-structure/population-trends (updated 30 Sep 2015; cited 2015 Sep Dec).

- 19. Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, et al. The care span: the importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Aff 2011;30:746–54. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Low LL, Vasanwala FF, Ng LB, Lb N, et al. Effectiveness of a transitional home care program in reducing acute hospital utilization: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:100 10.1186/s12913-015-0750-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee KH, Low LL, Allen J, et al. Transitional care for the highest risk patients: findings of a randomised control study. Int J Integr Care 2015;15 10.5334/ijic.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Low LL, Tan SY, Ng MJ, Mjm N, et al. Applying the integrated practice unit concept to a modified virtual ward model of care for patients at highest risk of readmission: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2017;12:e0168757 10.1371/journal.pone.0168757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Jonge KE, Jamshed N, Gilden D, et al. Effects of home-based primary care on Medicare costs in high-risk elders. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1825–31. 10.1111/jgs.12974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dreiher J, Comaneshter DS, Rosenbluth Y, et al. The association between continuity of care in the community and health outcomes: a population-based study. Isr J Health Policy Res 2012;1:21 10.1186/2045-4015-1-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Althaus F, Paroz S, Hugli O, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58:41–52. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blair T, Minkler M. Participatory action research with older adults: key principles in practice. Gerontologist 2009;49:651–62. 10.1093/geront/gnp049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nolan AHL. The practicing nurse. Sydney: W.B. Saunders Bailliere Tindall, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Timby BK. Fundamental nursing skills and concepts. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hart EBM. Action research for health and social care: a guide to practice. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Low LL, Liu N, Wang S, et al. Predicting frequent hospital admission risk in Singapore: a retrospective cohort study to investigate the impact of comorbidities, acute illness burden and social determinants of health. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012705 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Low LL, Liu N, Wang S, et al. Predicting 30-day readmissions in an Asian population: building a predictive model by incorporating markers of hospitalization severity. PLoS One 2016;11:e0167413 10.1371/journal.pone.0167413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rahman MA. ReasonPaB H, Some trends in the praxis of participatory action research. London: Sage, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chevalier JMaB DJ. Participation action research: theory and methods for engaged inquiry. United Kingdom: Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roland M, Dusheiko M, Gravelle H, et al. Follow up of people aged 65 and over with a history of emergency admissions: analysis of routine admission data. BMJ 2005;330:289–92. 10.1136/bmj.330.7486.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sandberg M, Jakobsson U, Midlöv P, et al. Case management for frail older people—a qualitative study of receivers' and providers' experiences of a complex intervention. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:14:14 10.1186/1472-6963-14-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988;15:351–77. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res 2015. 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Evans RG, Stoddart GL. Producing health, consuming health care. Soc Sci Med 1990;31:1347–63. 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90074-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm: Institute for future studies, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017839supp001.pdf (168.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017839supp002.pdf (164.4KB, pdf)