Abstract

Objectives

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) has caused a substantial burden in China, especially in Guangdong Province. Based on the enhanced surveillance system, we aimed to explore whether the addition of temperate and search engine query data improves the risk prediction of HFMD.

Design

Ecological study.

Setting and participants

Information on the confirmed cases of HFMD, climate parameters and search engine query logs was collected. A total of 1.36 million HFMD cases were identified from the surveillance system during 2011–2014. Analyses were conducted at aggregate level and no confidential information was involved.

Outcome measures

A seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model with external variables (ARIMAX) was used to predict the HFMD incidence from 2011 to 2014, taking into account temperature and search engine query data (Baidu Index, BDI). Statistics of goodness-of-fit and precision of prediction were used to compare models (1) based on surveillance data only, and with the addition of (2) temperature, (3) BDI, and (4) both temperature and BDI.

Results

A high correlation between HFMD incidence and BDI (r=0.794, p<0.001) or temperature (r=0.657, p<0.001) was observed using both time series plot and correlation matrix. A linear effect of BDI (without lag) and non-linear effect of temperature (1 week lag) on HFMD incidence were found in a distributed lag non-linear model. Compared with the model based on surveillance data only, the ARIMAX model including BDI reached the best goodness-of-fit with an Akaike information criterion (AIC) value of −345.332, whereas the model including both BDI and temperature had the most accurate prediction in terms of the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 101.745%.

Conclusions

An ARIMAX model incorporating search engine query data significantly improved the prediction of HFMD. Further studies are warranted to examine whether including search engine query data also improves the prediction of other infectious diseases in other settings.

Keywords: Hand, foot and mouth disease; Baidu index; Time series analysis; ARIMAX model

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Using a 4 year large-scale provincial-wide surveillance dataset on hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD), a seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model incorporating search engine query data (ARIMAX) was fitted to facilitate accurate and timely detection, and the robustness of the model was shown.

The assessment of the lag-specific associations between predictors and the HFMD incidence provided evidence for the importance of setting lag of the predictors in the ARIMAX model.

The increasing internet penetration in China may lead to an overestimation of the increasing trend in the HFMD incidence rate.

Ecological fallacy could not be ruled out because a higher web search frequency was unlikely to increase the risk of HMFD.

Introduction

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is a major public health problem in China, affecting over two million children annually.1 2 Notably, the incidence of HFMD in Guangdong Province exceeded 30 per 10 000 person years, which was more than four times the average national level.3 4 Mathematical models including multiple factors for predicting an outbreak of HMFD are urgently needed to reinforce an integrated management for monitoring, control and prevention of HFMD.

The autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model was used to predict hepatitis incidence using the historical surveillance data.5 In addition, the seasonal ARIMA models have also been used to predict the evolution of some major infectious diseases satisfactorily, such as malaria and hepatitis A,6 influenza,7 pneumonia,8 and dengue fever.9 Some studies showed that the addition of external variables (ARIMAX) in the ARIMA model (ie, Google search queries) might improve the prediction.10 11 Google search queries are the most commonly used data source for search studies around the world. For example, Google’s search engine has been used to detect influenza epidemics in areas with a large population of web search users because of its high correlation with the percentage of physician visits if a patient has influenza-like symptoms.12 A similar search engine in China is Baidu Inc (Baidu Index, BDI: http://index.baidu.com) which is popular because of the general unavailability of Google in the country. Baidu is now the most widely used search engine in China with massive internet behaviour data recorded, including concerns for HFMD.13 Moreover, information on some climate variables, such as temperature, humidity and rainfall, were also taken into account in predicting annual HFMD epidemics.14 Of these variables, temperature was the most frequently used parameter.3 4 15 16

We conducted the current study to examine whether the addition of external predictors (ie, BDI and temperature) improved the predictive capability of the model based on data from the enhanced surveillance system of HFMD in Guangdong, China. An early warning system for an HFMD outbreak might be based on the model to facilitate preventive strategies more effectively.

Methods

Ethics statement

This ecological study was based on official HFMD surveillance data in China. Analyses were conducted at aggregate level and no confidential information was involved. The research study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University.

Study site

Guangdong Province is situated in north latitude 20°15’N to 25°51’N and east longitude 109°75’E to 117°33’E, and has a population of 104 million according to the 2010 census. It has complex landforms through the latitude direction, that is, a series of mountains are located in the province from northeast to southwest, and it is adjacent to the South China Sea Coast. In general, Guangdong is an area of low latitude, high temperature and high humidity. An investigation of internet penetration in 2015 showed that Guangdong has the largest scale of netizens (internet users) and accounts for a third of the internet penetration in China.17

Data collection

Weekly case-based HFMD surveillance data from 2011 to 2014 were obtained from the National Centre for Public Health Surveillance and Information Services, China Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC). HFMD has been statutorily notifiable since a large outbreak in May 2008 and the enhanced national surveillance system has been described and validated in detail elsewhere.15 All HFMD cases were confirmed by the guideline for diagnosis and treatment of HFMD18 19 and were reported to the national surveillance system. Weekly incidence of HFMD was calculated using demographic data from the Annual Statistical Report of Guangdong (http://www.gdstats.gov.cn/tjsj/gdtjnj/). Daily meteorological data were obtained for the same period from the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System (http://cdc.nmic.cn/home.do) which is the oldest authorised meteorological department in China. Data on daily temperatures from six monitoring stations in Guangdong were aggregated into weekly average data at the provincial level. Daily search engine query data were obtained for the same period from Baidu Inc (https://index.baidu.com/).13 We searched Baidu using the keyword of ‘hand, foot, and mouth disease’ and counted the search frequency recorded by Baidu Inc. Daily search frequencies were also aggregated into weekly average data. All the information above was collected from January 2011 to December 2014 (a total of 208 weeks), and was included in the data analysis. No missing data were observed.

Data analysis

First, we used descriptive analysis to present the mean and SD of the weekly HFMD incidence, as well as the time series of weekly average temperature and BDI. Then we used the distributed lag non-linear model to examine the association between predictors and the HFMD incidence. Finally, we fitted the ARIMAX model to forecast the HFMD incidence. As we used aggregated data, subgroup analysis and interaction analysis were not applicable. All data analysis was conducted in R (version 3.3.2), using packages of ‘base’, ‘psych’, ‘lattice’, ‘TSA’, and ‘dlnm’.

Descriptive analysis

Measures of the minimum, median, maximum, mean and SD of weekly HFMD incidence (1/10 000), temperature (°C) and BDI were calculated. The pairwise association of predictors with the incidence of HFMD was examined using Pearson correlation analysis. A time series plot was used to show the weekly changing trend as well as the crude associations between each predictive variable and the outcome.

Distributed lag non-linear model

We used distributed lag non-linear model with quasi-Poisson distribution to calculate the relative risk (RR) between each predictor and the HFMD incidence and to provide evidence for setting the lag of the predictors in the ARIMAX model. The following equation was used: Log(incidence)=intercept + cb(predictor)+ns(time), where ‘incidence’ was the weekly HFMD incidence, ‘predictor’ was the temperature or BDI, and the ‘cb(predictor)’ was the cross-basis combining the basis matrices for exposure-response and lag-response relationships for the predictor. Both exposure-response and lag-response functions were specified as natural cubic spline (ns), with different degrees of freedom (df) of 3 and knots at log(4, df=3), respectively. ‘ns(time)’ was an ns fitted to the weeks of the year with df=3/year. All the dfs were specified as 3. As two peaks were found in the time series of the HFMD incidence, the use of three inflection points might thus be appropriate.20 In addition, as a sensitivity analysis we changed the lagged effect from 0 to 4 weeks of lag and examined the RRs of the predictors using the median value as reference.

ARIMAX model

A seasonal ARIMA model was fitted into the data of HFMD incidence, using the Box and Jenkins approach.21–24 Once the univariate model was selected, the multivariate models including external regressors could be elaborated. The following equation was used to obtain the predicting incidence series:

Where and was the moving average (MA) operator and autoregressive (AR) operator, respectively; and was the seasonal MA and AR operator, respectively; and and was the ordinary and seasonal difference components, respectively. denotes white noise, denotes external variables, and denotes the dependent variable (ie, incidence series).

To identify the order of MA and AR parameters, the structure of temporal dependence of stationary time series was assessed respectively, by the analysis of autocorrelation (ACF) and partial autocorrelation (PACF) functions. The Ljung-Box test was used to test whether the residuals were independent of the white noise. The fitness of the models was assessed by Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to indicate the fitness of models, with a lower AIC value indicating a better goodness of fit. Furthermore, the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) was used to assess the prediction accuracy during forecasting, with a lower value indicating a more accurate prediction.

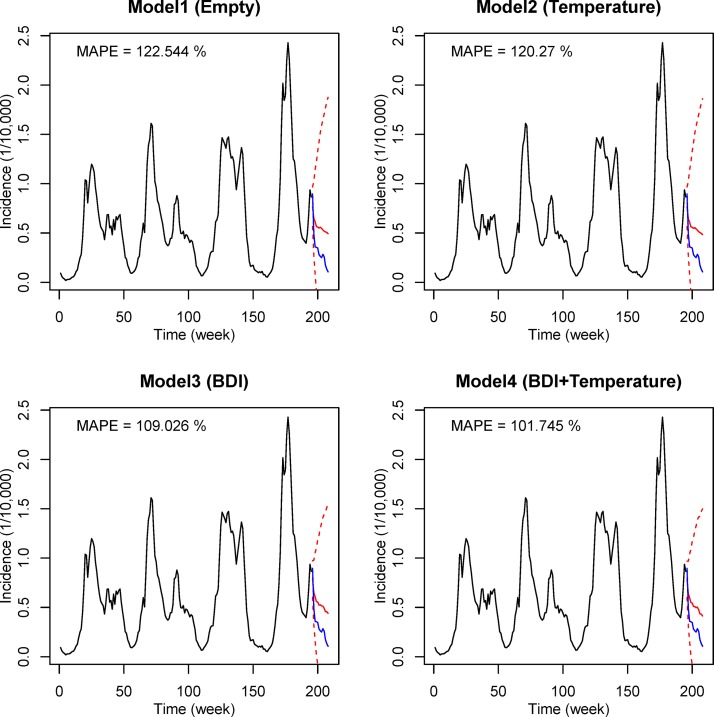

To estimate the forecast accuracy of the models, we divided the data into two datasets including a training dataset (195 weeks) and a testing dataset (13 weeks, about one quarter of a year). As the MAPE values exceeded 100 for all four ARIMAX models—ie, models (1) based on surveillance data only, and models with addition of (2) temperature, (3) BDI and (4) both temperature and BDI in the 13th week (MAPE values ranged from 102% to 123%; table not shown), indicating a poor forecasting performance after 13 weeks—this suggests that the model predicts the HFMD risk up to 13 weeks in advance.

Results

Descriptive statistics

During 2011–14, 1.358 million probable cases of HFMD in Guangdong were identified from the China CDC surveillance system. The incidence rates reached a steady state at more than 6 cases per 1000 person weeks in Guangdong. The median (range) of temperature and BDI was 23.070 (8.795–29.893)°C and 3296 (516–32596) units, respectively (table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix among weekly hand, foot, and mouth disease, temperature and BDI in Guangdong from 2011 to 2014

| Mean±SD | Minimum | Median | Maximum | Correlation | ||

| BDI | Temperature | |||||

| Incidence (1/10 000) | 0.609±0.504 | 0.018 | 0.482 | 2.428 | 0.794* | 0.657* |

| Temperature (°C) | 21.774±6.038 | 8.795 | 23.07 | 29.893 | 0.376* | 1.0 |

| BDI (unit) | 5414.317±6090.975 | 516 | 3296 | 32 596 | 1.0 | – |

*p<0.001.

BDI, Baidu Index.

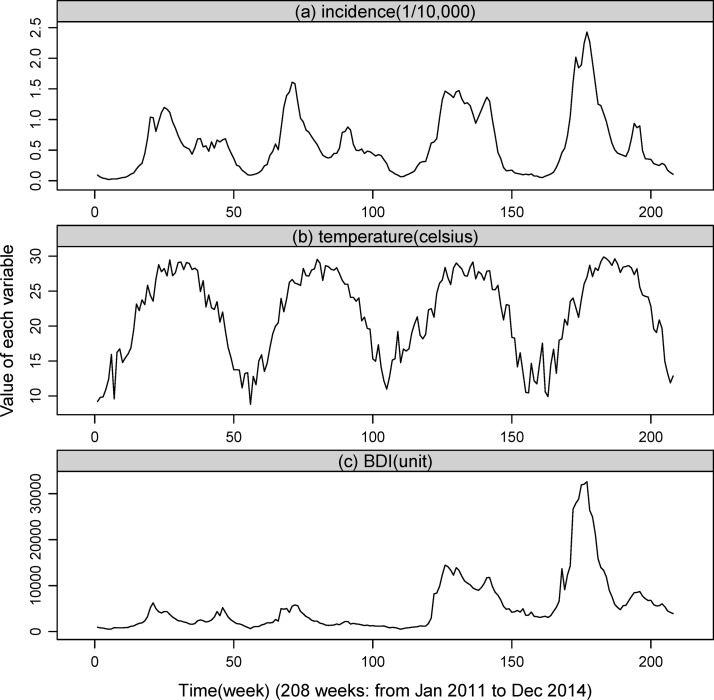

As expected, both time series of weekly incidence and predictors for HFMD in Guangdong showed seasonal peaks of activity (figure 1), with a major peak from spring to early summer followed by a smaller peak in autumn. A consistent pattern was found for the time series of incidence and BDI. table 1 shows significant correlations between BDI and HFMD incidence (r=0.794, p<0.001) or temperature (r=0.376, p<0.001), and between temperature and incidence (r=0.657, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Time series of weekly incidence and predictors for hand, foot, and mouth disease in Guangdong province, 2011–14.

Distributed lag non-linear model

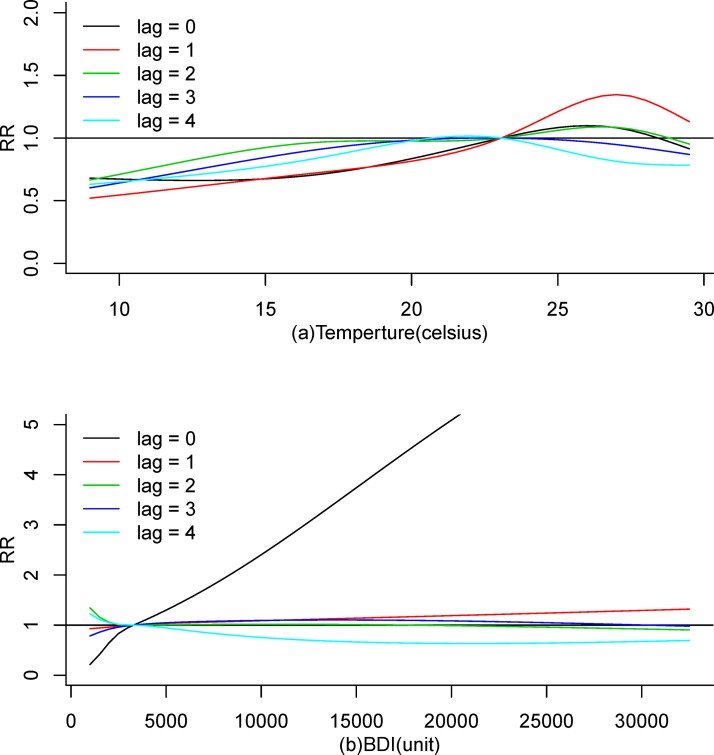

For the lag-specific predictor-response relationship, both temperature and BDI were positively associated with the incidence of HFMD (figure 2). The lines with a relatively greater slope were lag 0 and 1 week for temperature, and lag 0 week for BDI, compared to other lag-specific lines. A visually non-linear pattern was found for the correlation between the HFMD incidence and temperature, whereas no evidence for a non-linear pattern with BDI was found. The 1 week lag-specific lines of temperature-incidence association and the reference line (RR=1.0) overlapped at around 24°C.

Figure 2.

Lag-specific predictors—RR curves at various lags. BDI, Baidu Index.

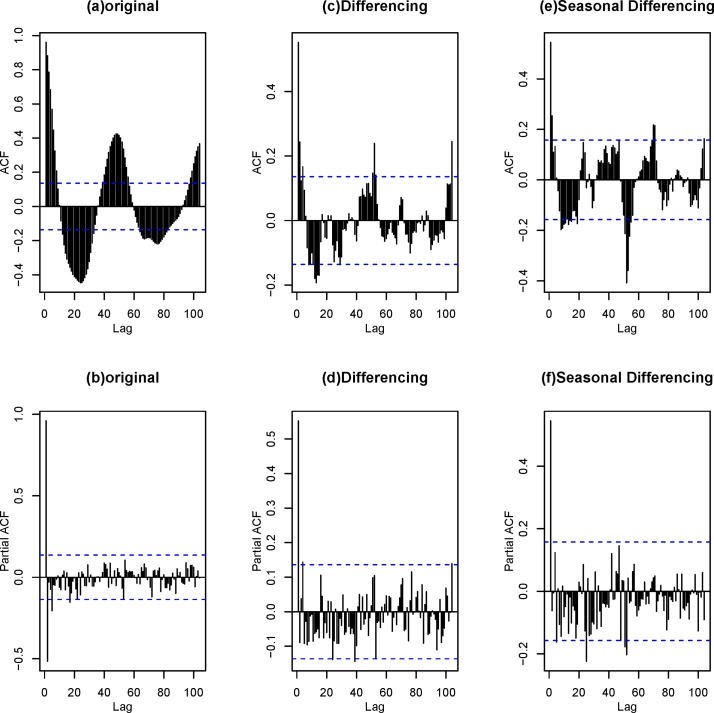

Stationarity and differencing

The temporal dependence and seasonal variation were found by the plots of ACF and PACF (figure 3a and b). After a first-order differencing, a significant cut-off at lag 1 week and another at lag 52 weeks were observed on the plot ACF (figure 3c). These two cut-offs were less marked on the plot PACF (figure 3d), compared with the plot ACF. Then, after a 52-week seasonal differencing, the series became stationary (figure 3e and f). Therefore, the following univariate multiplicative ARIMA (1, 1, 1 1, 0, 1)52 model was fitted to predict the HFMD incidence (model 1, table 2).

Figure 3.

Autocorrelation function (ACF) and partial ACF (PACF) plots of original and differencing hand, foot, and mouth disease incidence.

Table 2.

Characteristics of ARIMAX models: coefficients, p value for predictors and Ljung-Box test, AIC

| Model | Variable | Coefficients | p Value | ||||||

| AR | MA | SAR | SMA | Temperature* | BDI | Ljung-Box test | AIC | ||

| Model 1 | ARIMA (1,1,1 1,0,1)52 | 0.415 | 0.191 | 0.717 | −0.441 | – | – | 0.119 | −316.511 |

| Model 2 | ARIMA+temperature | 0.413 | 0.191 | 0.722 | −0.448 | 0.001 | – | 0.125 | −314.596 |

| Model 3 | ARIMA+BDI | 0.358 | 0.112 | 0.621 | −0.312 | – | 0.026 | 0.227 | −345.332† |

| Model 4 | ARIMA+temperature+BDI | 0.336 | 0.130 | 0.617 | −0.309 | 0.002 | 0.027 | 0.221 | −343.976† |

*Temperature was included with one lag.

†p<0.001 compared with model 1.

AIC, Akaike information criterion; AR, autoregressive; ARIMA, autoregressive integrated moving average model; ARIMAX, ARIMA with external variables; MA, moving average; SAR, seasonal autoregressive; SMA, seasonal moving average.

Autoregressive integrated moving average model with external variables (ARIMAX)

Both lag 1 week transformed temperature and BDI were significantly associated with the HFMD incidence in the ARIMAX models (table 2). The Ljung-Box test of the residuals for all models could not reject the null hypothesis that the model does not exhibit a lack of fit (p>0.05). The ARIMAX model with BDI as predictor showed a better goodness of fit than the model without external variables, and the model with temperature only (AIC=−345.332 vs −316.511, and −314.596, respectively). For the forecast accuracy, the model including both temperature and BDI showed a smaller MAPE than others (MAPE=101.745%, the smaller the better) (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forecasting one quarter for hand, foot, and mouth disease incidence. BDI, Baidu Index; MAPE, mean absolute percentage error.

Discussion

Our study showed that using an ARIMAX model incorporating BDI improved the prediction of HFMD incidence significantly, and the addition of temperature did not improve the fitness of the model. Our results suggested that using a multivariate ARIMAX model provides better prediction than a univariate model, and that search engine queries such as BDI might be further taken into account in routine HFMD surveillance systems. This model, if it can be replicated in other settings, might be useful for the evaluation of new intervention strategies against HFMD worldwide.

We used the time series analysis to allow for the development of robust and reliable ARIMAX models with a correct level of validity that fits provincial-wide HFMD incidence data from 2011 to 2014. Our results supported the use of BDI in further prediction models to help the development of an appropriate prevention programme in China. Moreover, the current study demonstrated a lag-specific relationship between predictors, such as average temperature and BDI, and the HFMD incidence. The predominant effect of temperature was observed after 1 week lag, but no lag effect for BDI was found, suggesting real time monitoring and predicting should be more appropriate for BDI. Our finding of the lag of 1 week was consistent with the incubation period of enteroviruses and the potential delay in parental awareness,25 which was also reported in a previous study in Hong Kong.26 Although the peak of the temperature was consistently shown as 1 week ahead of the peak of HFMD incidence from the surveillance reports, the BDI showed more timely and close association with the HFMD incidence.

Our results were consistent with some earlier studies showing that climatic variables, such as temperature, played a key role in the HFMD transmission.20 27 Previous laboratory studies showed that under 35°C, higher temperature was associated with a higher survival rate of enteroviruses.28 29 Furthermore, higher temperature might also lead to more frequent outdoor activities, which would subsequently lead to a higher risk of HFMD. A study by Zhang et al found a bimodal distribution for the effect of temperature on HFMD.30 Our previous study used a non-parametric method (ie, classification and regression tree) and also showed a significant association between temperature and the incidence of HFMD.20

By incorporating search engine query data, we showed that the fitness of the prediction model improved significantly, suggesting the search engine query data might provide complementary information in terms of monitoring of infectious diseases. Guangdong is one of the most developed provinces in China with a high internet penetration (72.4%).17 As Baidu Inc is the largest Chinese search engine, its search queries could be a good representation of the needs of people’s lives, especially in regions with high internet penetration. Moreover, as search queries can be processed quickly, applying the ARIMAX model with real time search engine data may provide an opportunity for monitoring and early detection of HFMD, and perhaps other infectious diseases in other settings. Previous studies also reported the use of search engine query data in infectious disease prediction. A study by Liu et al used the time-series classification and regression tree models based on BDI to develop a predictive model for dengue fever outbreaks in Guangzhou and Zhongshan, China, which has shown satisfactory predictive ability.31

The infectious disease surveillance system might benefit from taking into account both search engine query data and temperature in the ARIMAX model, and might become more timely and efficient. Due to the lack of manpower and material resources, the surveillance system in low-to-middle income countries including China is largely inefficient.32 Most cases were reported through a stepwise hierarchical reporting system, that is, from the lowest to the highest hierarchy in a sequence of town, county, city, province, and the national CDC. The proposed model incorporating the timely internet search engine queries might provide opportunities to improve the detection ability of the surveillance system substantially. A study by Ginsberg et al introduced a method of analysing large numbers of Google search queries to track influenza-like illness in the general population, and found that the current level of weekly influenza activity in each region of the USA could be accurately estimated with a reporting lag of about 1 week.12

However, there are some limitations to be noted. First, time series analysis requires data over long periods (ie, 5 years for a seasonal period of 52 weeks), which are often difficult to obtain on a large scale. In our study, the BDI of HFMD in Guangdong was available only after 2011. An ongoing surveillance programme may generate more long-term data which can be used to improve the predictive model greatly. Second, data on some other climatic variables such as humidity, barometric pressure and rainfall30 33 were not available in the current study. Further studies are warranted to examine whether including these variables would improve the prediction. Thirdly, the ARIMAX model, although based on provincial-wide data, does not take into account geographical disparities within the province. Further studies accounting for geographical disparities, such as rural or urban, may be useful. Fourthly, ecological fallacy could not be ruled out because higher web search frequency would not necessarily increase the risk of HFMD. Fifthly, although our study was based on large-scale provincial-wide data, generalizability of our results to other populations with a lower incidence rate of HFMD might not be straightforward. However, the use of the ARIMAX model incorporating web search query data in the detection and prediction of other infectious diseases might provide an opportunity for re-allocating healthcare resources more efficiently, not only in China, but also in other settings with a reasonable surveillance system and web penetration rate. Finally, the increase of BDI may be partly due to the increase in internet penetration in China during the same period. According to the China Internet Network Information Centre (CNNIC), the internet penetration increased from 60.4% in 2011 to 68.5% in 2014.34 However, we could not distinguish the increase in BDI due to the true increase in HFMD cases from the increase due to internet penetration. The overestimation of BDI, if anything, may lead to an overestimation of the association between BDI and HFMD incidence.

Conclusion

An ARIMAX model incorporating search engine query data significantly improved the prediction of HFMD. Further studies are warranted to examine whether the inclusion of search engine query data in the ARIMAX model also improves the prediction of other infectious diseases in other settings with a large population of internet users.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention for providing the data of notified hand, foot and mouth disease cases. We thank China Meteorological Agency for providing meteorological data of temperature. We thank Baidu Corporation for providing search engine query data of “hand, foot and mouth disease”.

Footnotes

Contributors: ZD participated in the design, performed data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. WZ, DZ and SY participated in the design and results interpretation, and helped to finalise the manuscript. YH and LX participated in the design and supervised the study, participated in interpretation of results, and helped to finalise the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the contents of the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number: 81473064] and the Guangzhou Science and Technology Program projects [grant number: 201506010072]. Non-financial associations may be relevant to the submitted manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was based on official hand, foot and mouth disease surveillance data in Guangdong. Analyses were conducted at aggregate level and no confidential information was involved. The research study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from China CDC but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study and so are not publicly available.

References

- 1. National Health and Family Planning Commission of China. The National Statutory Epidemic Situation of Infectious Diseases of China. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/jkj/s2907/new_list.shtml (cited 2017-03-01).

- 2. Zhu Q, Hao Y, Ma J, et al. Surveillance of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Mainland China (2008-2009). Biomed Environ Sci 2011;24:349–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deng T, Huang Y, Yu S, et al. Spatial-temporal clusters and risk factors of hand, foot, and mouth disease at the District level in Guangdong Province, China. PLoS One 2013;8:e56943 10.1371/journal.pone.0056943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang W, Du Z, Zhang D, et al. Boosted regression tree model-based assessment of the impacts of meteorological drivers of hand, foot and mouth disease in Guangdong, China. Sci Total Environ 2016;553:366–71. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wei W, Jiang J, Liang H, et al. Application of a combined model with Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) and Generalized Regression Neural Network (GRNN) in forecasting hepatitis incidence in Heng County, China. PLoS One 2016;11:e156768 10.1371/journal.pone.0156768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nobre Flvio Fonseca, Monteiro ABS, Telles PR, et al. Dynamic linear model and SARIMA: a comparison of their forecasting performance in epidemiology. Stat Med 2001;20:3051–69. 10.1002/sim.963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Quénel P, Dab W. Influenza A and B epidemic criteria based on time-series analysis of health services surveillance data. Eur J Epidemiol 1998;14:275–85. 10.1023/A:1007467814485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choi K, Thacker SB. An evaluation of influenza mortality surveillance, 1962-1979. I. Time series forecasts of expected pneumonia and influenza deaths. Am J Epidemiol 1981;113:215–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gharbi M, Quenel P, Gustave J, et al. Time series analysis of dengue incidence in Guadeloupe, French West Indies: forecasting models using climate variables as predictors. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:166 10.1186/1471-2334-11-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kongcharoen C, Kruangpradit T. Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average with Explanatory Variable (ARIMAX) Model for Thailand Export. the 33rd International Symposium on Forecasting. Seoul 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wangdi K, Singhasivanon P, Silawan T, et al. Development of temporal modelling for forecasting and prediction of malaria infections using time-series and ARIMAX analyses: a case study in endemic districts of Bhutan. Malar J 2010;9:251 10.1186/1475-2875-9-251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ginsberg J, Mohebbi MH, Patel RS, et al. Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature 2009;457:1012–4. 10.1038/nature07634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wikipedia. Baidu: Chinese Web Services Company. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baidu (cited 2016-10-1).

- 14. Feng H, Duan G, Zhang R, et al. Time series analysis of hand-foot-mouth disease hospitalization in Zhengzhou: establishment of forecasting models using climate variables as predictors. PLoS One 2014;9:e87916 10.1371/journal.pone.0087916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xing W, Liao Q, Viboud C, et al. Hand, foot, and mouth disease in China, 2008–12: an epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:308–18. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70342-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang Y, Deng T, Yu S, et al. Effect of meteorological variables on the incidence of hand, foot, and mouth disease in children: a time-series analysis in Guangzhou, China. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:134 10.1186/1471-2334-13-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. China Report Web. Investigation of scale and penetration of netizens by provinces in China. Available from http://market.chinabaogao.com/it/032423K952016.html.

- 18. National Health and Family Planning Commission of China. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of HFMD. 2010.

- 19. National Health and Family Planning Commission of China. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of HFMD. 2008.

- 20. Du Z, Zhang W, Zhang D, et al. The threshold effects of meteorological factors on hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) in China, 2011. Sci Rep 2016;6:36351 10.1038/srep36351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Helfenstein U. The use of transfer function models, intervention analysis and related time series methods in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 1991;20:808–15. 10.1093/ije/20.3.808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Allard R. Use of time-series analysis in infectious disease surveillance. Bull World Health Organ 1998;76:327–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nobre FF, Monteiro AB, Telles PR, et al. Dynamic linear model and SARIMA: a comparison of their forecasting performance in epidemiology. Stat Med 2001;20:3051–69. 10.1002/sim.963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ljung GM, BOX GEP, Gep BOX. On a measure of lack of fit in time series models. Biometrika 1978;65:297–303. 10.1093/biomet/65.2.297 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. WebMD. Topic Overview: Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease. http://www.webmd.com/children/guide/hand-foot-and-mouth-disease-topic-overview#1 (cited 2017-04-26).

- 26. Ma E, Lam T, Wong C, et al. Is hand, foot and mouth disease associated with meteorological parameters? Epidemiol Infect 2010;138:1779–88. 10.1017/S0950268810002256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang W, Du Z, Zhang D, et al. Quantifying the adverse effect of excessive heat on children: an elevated risk of hand, foot and mouth disease in hot days. Sci Total Environ 2016;541:194–9. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.09.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arita M, et al. Temperature-sensitive mutants of enterovirus 71 show attenuation in cynomolgus monkeys. J Gen Virol 2005;86:1391–401. 10.1099/vir.0.80784-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kung Y-H, Huang S-W, Kuo P-H, et al. Introduction of a strong temperature-sensitive phenotype into enterovirus 71 by altering an amino acid of virus 3D polymerase. Virology 2010;396:1–9. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang W, Du Z, Zhang D, et al. Assessing the impact of humidex on HFMD in Guangdong Province and its variability across social-economic status and age groups. Sci Rep 2016;6:18965 10.1038/srep18965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu K, Wang T, Yang Z, et al. Using Baidu search index to predict Dengue outbreak in China. Sci Rep 2016;6:38040 10.1038/srep38040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Q, Jiang F. Comparison of infectious disease surveillance systems in China and abroad (In Chinese). Digest of World Latest Medical Information. 2015.

- 33. Zhao D, Wang L, Cheng J, et al. Impact of weather factors on hand, foot and mouth disease, and its role in short-term incidence trend forecast in Huainan City, Anhui Province. Int J Biometeorol 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. China Report Web. Statistics of the scale and penetration of netizens during 2011-2014 in Guangdong.http://data.chinabaogao.com/it/2016/032323KB2016.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.