Abstract

Introduction

Adverse neurocognitive outcomes are still an important cause of morbidity and mortality after cardiac surgery. The most common neurocognitive disorders after conventional cardiac surgery are postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), stroke and delirium. Minimal invasive cardiac procedures have recently been introduced into practice. Endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting (Endo-CABG) is a minimal invasive cardiac procedure based on the conventional CABG procedure. Neurocognitive outcome after minimal invasive cardiac surgery, including Endo-CABG, has never been studied. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to examine neurocognitive outcome after Endo-CABG.

Methods and analysis

We will perform a prospective observational cohort study including 150 patients. Patients are categorised into three groups: (1) patients undergoing Endo-CABG, (2) patients undergoing a percutaneous coronary intervention and (3) a healthy volunteer group. All patients in the Endo-CABG group will be treated following a uniform, standardised protocol. To assess neurocognitive outcome after surgery, a battery of six neurocognitive tests will be administered at baseline and at 3-month follow-up. In the Endo-CABG group, a neurological examination will be performed at baseline and postoperatively and delirium will be scored at the intensive care unit. Quality of life (QOL), anxiety and depression will be assessed at baseline and at 3-month follow-up. Satisfaction with Endo-CABG will be assessed at 3-month follow-up. Primary endpoints are the incidence of POCD, stroke and delirium after Endo-CABG. Secondary endpoints are QOL after Endo-CABG, patient satisfaction with Endo-CABG and the incidence of anxiety and depression after Endo-CABG.

Ethics and dissemination

The neurological outcome after minimal invasive coronary artery surgery study has received approval of the Jessa Hospital ethics board. It is estimated that the trial will be executed from December 2016 to January 2018, including enrolment and follow-up. Analysis of data, followed by publication of the results, is expected in 2018.

Trial registration number

Keywords: postoperative cognitive dysfunction, neurological outcome, minimal invasive coronary artery surgery, stroke, delirium, coronary heart disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to date to assess neurological outcome after minimal invasive cardiac surgery.

A large battery of neurocognitive tests will be applied to assure a thorough and accurate assessment of the neurocognitive function after endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting (Endo-CABG).

The neurocognitive outcome of patients undergoing Endo-CABG will not be compared with patients undergoing conventional CABG in this randomised controlled trial.

Introduction

Background and rationale

Despite improvements in surgical techniques, perfusion systems and perioperative guidelines, adverse neurological outcomes are still an important cause of morbidity and mortality after cardiac surgery.1 2 Consequently, neurological outcome after cardiac surgery remains an important issue of interest since neurological complications have a major impact on quality of life (QOL) and healthcare costs after cardiac surgery.3–5 The most common neurological disorders after cardiac surgery are postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), stroke and delirium.6–8

POCD is broadly defined as a decline in cognition temporally associated with surgery. It is recognised to reflect a disturbance of brain function related to surgery.9 10 Due to the multifactorial nature of POCD, it is difficult to pinpoint one major cause.11–13 Short-term POCD or cognitive decline lasting up to 6 weeks postsurgery is usually transitory and is observed in 25%–50% of all patients after conventional cardiac surgery.6 14 Long-term POCD or cognitive decline 3–6 months after surgery occurs in 10%–30% of cardiac patients and is associated with major consequences and financial implications such as a higher risk of leaving the labour market and an increased mortality.4 Incidence of POCD varies strongly since there are no universally accepted guidelines and analytic criteria for the diagnosis of POCD. The ‘1995 statement of consensus on assessment of neurobehavioral outcomes after cardiac surgery’, however, highlighted the most reliable and recommended battery of neuropsychological testing to assess for POCD in clinical studies.15

The following battery of tests has been recommended in the consensus statement15 16:

Rey auditory verbal learning test to test verbal memory (RAVLT)

Trail making test A and B to test attention (TMT A and B)

Grooved Pegboard Test to test fine motor function.

Additional recommendations of the consensus statement to conduct reliable POCD testing are15:

baseline testing;

at least one assessment of POCD 3 months postoperatively;

a control group and a comparative group;

the same person tests both preoperatively and postoperatively;

clinical neurological investigation is necessary.

Adherence to consensus statement recommendations in studies investigating POCD after cardiac surgery however is very low. For example, only 25% of all prospective cohort studies using a control group included all four tests named in the consensus statement.17

Additional tests on top of the tests stated in the consensus statement such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)-III digit span test and the WAIS-III digit symbol-coding test can be performed to assess additional neurological outcome measures. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is often used as a supplemental indicator of pre-existing neurological decline.

The RAVLT has a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80 and an adequate validity and good reliability.18 TMT A and B have a high validity and reliability.19 20 The Grooved Pegboard Test has a good validity and a high reliability.21 The WAIS-III digit span test and WAIS-III digit symbol-coding test have a high validity and a high reliability.22 The MMSE has a moderate validity and reliability.23

The statistical methods used to define the cut-off point between POCD and normal variation in cognitive function also vary widely.24 Commonly used statistic criteria are a percentage change from baseline in a defined number of tests (usually a decline of >20% in at least two tests) or an absolute decline from baseline scores greater than a predefined proportion of the SD in at least two tests.24 These statistical methods have been criticised because they do not relate cognitive data from age-matched healthy controls and also fail to assess learning effects and normal variability and cognitive decline in a healthy population over the same period. The Reliable Change Index (RCI) is an alternative statistical method that is increasingly used in POCD research. RCI relates the changed scores to the normal test–retest variability in an age-matched control population.24

Stroke is also an important neurological complication after cardiac surgery with an incidence of 1%–5%.19 20 Stroke is caused by disturbances in the blood supply to the brain. Most frequently, these disturbances are caused by thromboembolic events, general hypoperfusion or ruptured vessels in the brain. The risk of stroke is highest the first few days after cardiac surgery and is diagnosed based on neurological evaluation and signs on CT or MRI scan.6 8 25

Finally, delirium is characterised by acute onset attention disorders and fluctuating changes in the mental state of the patient.26 The aetiology of delirium is usually multifactorial.26 Delirium can easily be diagnosed using the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) score.26 The CAM-ICU score has a high validity and reliability.27 Studies have consistently demonstrated an incidence of postoperative delirium between 5% and 46% after cardiac surgery.28–30

New developments in cardiac surgery have recently led to the introduction of minimal invasive cardiac procedures into practice. These minimal invasive cardiac procedures are proven to be feasible and have excellent procedural and short-term outcomes (eg, in hospital mortality, hospitalisation time, scar healing, wound infections and postoperative recovery).31–33 Endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting (Endo-CABG) is a minimal invasive cardiac procedure based on the conventional CABG procedure but avoids a median sternotomy using a thoracoscopic technique. The Endo-CABG procedure is used to treat patients with multivessel coronary artery disease. Benefits of this procedure include reduced postoperative pain, reduced duration of hospital stay and fast recovery and return to work.32 33 Retrograde arterial perfusion (RAP) during minimal invasive cardiac procedures, however, may be associated with a higher incidence of neurological complications.34 In patients with severe (grades IV and V) aortic atherosclerosis, RAP has clearly been shown to increase the risk of cerebral embolic complications.34 However, neurocognitive outcome after minimal invasive cardiac surgery, including Endo-CABG, has never been studied.

The main objective of the neurological outcome after minimal invasive coronary artery surgery (NOMICS) study is to examine neurocognitive outcome and the incidence of neurological complications after Endo-CABG.

Primary objective

Assessment of the incidence of POCD, stroke and delirium after minimal invasive CABG (Endo-CABG).

Secondary objectives

to compare QOL before Endo-CABG and 3 months after Endo-CABG

to study patient satisfaction with Endo-CABG

to study patient satisfaction with the performed tests

to study the influence of various demographic and perioperative variables on neurological outcome after Endo-CABG

to compare the incidence of anxiety and depression before Endo-CABG and 3 months after Endo-CABG.

Methods and analysis

Study design

The NOMICS study is a single-centre prospective observational cohort study of 150 patients. The study is being performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the ethics committee of the Jessa Hospital in Hasselt (registration number B243201630254). Informed consent will be obtained from all participants. The study is implemented in line with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) statement.35 The final report will follow the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist for cohort studies.36

Population

Consecutive adult patients undergoing Endo-CABG will be enrolled in the present study. In line with the ‘1995 statement of consensus on assessment of neurobehavioral outcomes after cardiac surgery’, a comparative group and a control group will also be enrolled in this study in a 1:1:1 ratio (table 1). The comparative group consists of patients undergoing an elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). This group is included to investigate whether the observed neurological outcomes in the Endo-CABG group are not related to normal comorbidities in cardiovascular patients. It should be noted that PCI itself may be associated with impaired neurological outcome.37 The control group consists of healthy volunteers to eliminate natural variation in neurophysiological testing and to exclude the learning effect that can occur when repeated neurophysiological testing is performed.

Table 1.

Study groups

| Group | Intervention |

| Endo-CABG, surgical group (minimal invasive cardiac surgery group) |

Procedure/surgery: Endo-CABG minimal invasive cardiac intervention Other names: minimal invasive coronary artery bypass grafting |

| PCI, surgical control group (comparative minimal invasive procedure) |

Procedure/surgery: PCI stenting procedure Other names: percutaneous coronary intervention |

| Healthy volunteer, control group (to exclude learning effect or natural variation in neurological testing) |

No intervention This group will be age matched and sex matched |

Endo-CABG, Endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

All patients planned for Endo-CABG and PCI will be informed about the study at their preoperative visit by the cardiac surgeon and interventional cardiologist, respectively, and will be provided with a patient information sheet. Healthy volunteers will be recruited from spouses of patients and healthcare workers and will be age matched and sex matched. Interested patients will receive an appointment with the study investigator (FV) and will be assessed for eligibility. Detailed eligibility criteria are listed in table 2. The purpose, procedures and potential risks and benefits of the study will be explained thoroughly to all participants who meet the eligibility criteria by FV. If interested, a written informed consent will be obtained from each participant. The participants will be able to withdraw from the study at any time without consequences for therapy. This trial will be performed at a high volume institution (Jessa Hospital, Hasselt, Belgium). Based on the number of selected procedures performed annually in the Jessa Hospital, it is estimated that the trial will be executed from December 2016 to January 2018, including enrolment and follow-up.

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|

|

Endo-CABG, Endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

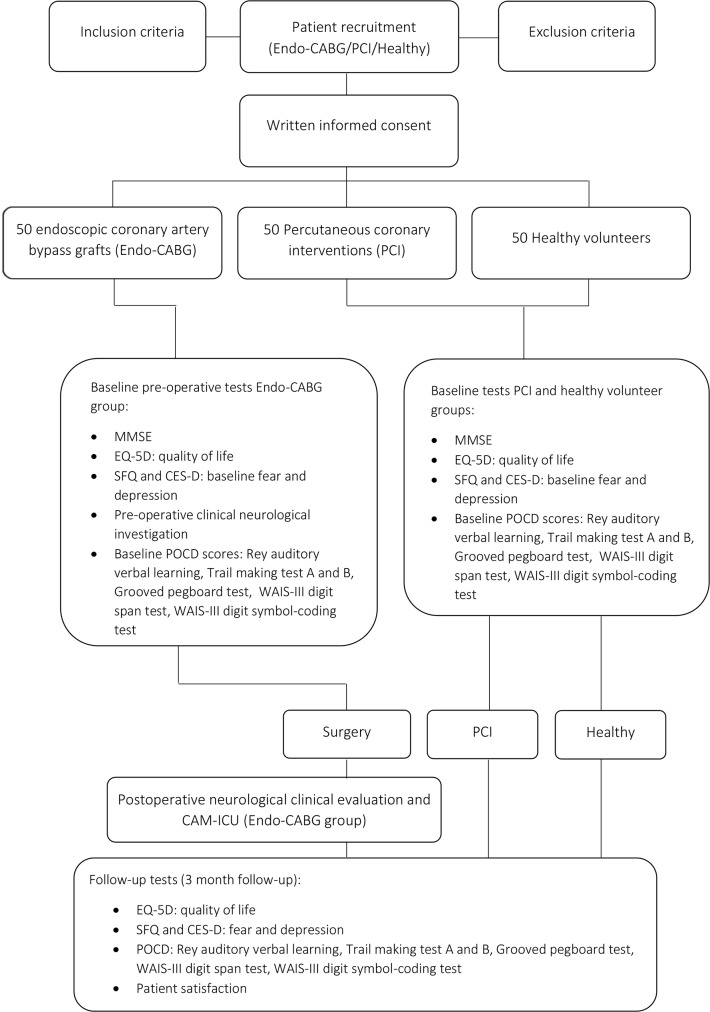

Outcome measures

Outcome measures in the domains of neurological outcome (POCD and MMSE), QOL, patient satisfaction with Endo-CABG and performed tests, anxiety and depression will be assessed at baseline and 3 months after intervention or baseline testing (figure 1). Delirium will be assessed daily during intensive care unit and medium care stay (3–4 days), and stroke will be assessed during hospital stay and at the 3-month follow-up appointment in case of a clinical suspicion. Patients who are unable to come to the hospital for follow-up will be tested at home.

Figure 1.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments. CAM-ICU, Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression; Endo-CABG, Endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; POCD, postoperative cognitive dysfunction; SFQ, Surgical Fear Questionnaire; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.

Primary outcome measures

Primary endpoints are:

The incidence of POCD at 3 months after surgery. A battery of four tests (RAVLT, TMT A and B and the Grooved Pegboard Test) mentioned by the ‘statement of consensus on assessment of neurobehavioral outcomes after cardiac surgery’, published in 1995 supplemented with two additional tests (ie, the WAIS-III digit span test and WAIS-III digit symbol-coding test) will be administered to determine the cognitive outcome.15

The incidence of stroke. A baseline neurological examination will be performed by a neurologist to register preoperative neurological deficits. In case of clinical suspicion of new neurological deficits by the attending intensive care specialist and/or neurologist, a brain CT scan or MRI scan will be performed to confirm the diagnosis of stroke.

The incidence of delirium. Delirium will be assessed with the CAM-ICU score.26

Secondary outcome measures

The following outcomes will also be assessed (see also figure 1):

QOL, measured by the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire38 to determine the effect of the intervention (Endo-CABG or PCI) on QOL;

depression, measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) questionnaire,39 and anxiety, measured by the Surgical Fear Questionnaire (SFQ).40 As recommended by the consensus statement (1995),15 both mood state assessments will be performed concurrently with the neuropsychological assessments because the performance of neuropsychological tests can be influenced by mood state;

patient satisfaction with Endo-CABG and performed tests, assessed with an 11-point numerical rating scale (where 0=not satisfied at all and 10=extremely satisfied);

assessment of predictors of poor neurological outcome after Endo-CABG. The predictive value of various demographic (ie, age and gender) and perioperative variables on neurological outcome after Endo-CABG will be assessed.

The EQ-5D has a limited validity and a moderate reliability.41 The CES-D and SFQ have a good validity and reliability.40 42

Baseline assessment measurements

In addition to the primary and secondary outcome measures, the researcher will also record participants’: age, gender, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification and highest level of education.

Data collection methods and management

All neurocognitive tests are performed by one single researcher in an isolated room. This study investigator is extensively trained for this specific test battery by a an experienced neuropsychologist. The preoperative neurological examination will be performed by an experienced neurologist. Consequently, standardised testing without interobservational variation will be guaranteed. Baseline tests will be performed in the Endo-CABG group, the PCI group and the control group. Baseline testing will be performed 2–14 days prior to procedure (see figure 1).

All data of 150 participants will be anonymously collected on paper at Jessa Hospital. The patient records will be kept in a locker until entered on password-protected computers. The entered data will be double checked by two independent researchers to minimise human errors. All patients enrolled will be carefully monitored until 3 months after surgery or baseline testing. The whole study will be supervised by members of the anaesthesiology department at Jessa Hospital.

Perioperative procedure (Endo-CABG group)

All patients in the Endo-CABG group will be treated following a uniform, standardised protocol for anaesthesia, surgical techniques and extracorporeal circulation to reduce treatment heterogeneity within the study group (see online supplementary appendix file). This protocol includes recently recommended neuroprotection methods in an attempt to minimise the risk of poor neurological outcome after cardiac surgery.

bmjopen-2017-017823supp001.pdf (352.7KB, pdf)

Statistical methods

POCD is defined as a decline in performance on neuropsychological assessment between baseline and 3-month follow-up beyond natural variation and learning effects. We used the RCI to control for natural variation or, in other words, the test–retest variability inherent in a matched normative data set.10 The RCI or z-score provides an estimate of the probability that a patient’s change in test score is reliable and not due to chance.10 The learning effect occurs because repeated administration of a test increases the knowledge of the test structure and thus performance tends to improve with repeated administration.17 We used a healthy control group to control for learning effects and natural variation. We used a PCI group to separate the effects of surgery from those of underlying disease.

The individual RCI scores will be calculated as follows: for each patient, the baseline score from each test will be subtracted from the follow-up score, giving Δx. The same will be done in the control group, giving Δxc. The mean change on that test in the control group will then be subtracted from Δx to eliminate practice effects. This result will then be divided by the SD of Δxc to eliminate the effect of natural variation in test performance. This is called a Z-score. The RCI is defined as the sum of the Z-scores of all tests. The difference score is computed such that a positive change reflects improvement and vice versa.

POCD in an individual patient is defined as an RCI ≤−1.645 (significance level 5%) or Z-score ≤−1.645 in at least two different tests.

Stroke is defined as a new neurological deficit presenting in hospital combined with signs of recent ischaemic cerebral infarction on brain CT or MRI. Patients with a postoperative stroke within the 3-month observation period will automatically also be classified in the POCD group.

Delirium is defined by the CAM-ICU test, and the result will be dichotomised. The QOL will be tested using a Mann-Whitney U test at significance level 5%. The group RCI scores will be compared using analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis.

Sample size

Sample size calculation will be based on expected neurocognitive outcome assessed with a battery of neurocognitive tests. Based on a previous study,11 we assume a mean SD of 3.567 for the difference score of a battery of neurocognitive tests. Therefore, to detect a significant change in performance on a battery of neurocognitive tests between baseline and 3-month follow-up with a power of at least 90% at a significance level of 0.05, 132 patients will be required (44 in each of the three study groups). The sample size will be inflated to 50 participants per group (150 in total) to account for a possible 12% loss to follow-up.

Discussion

The present study will be the first study to date to investigate the incidence of poor neurocognitive outcome 3 months after Endo-CABG. Minimal invasive cardiac procedures including Endo-CABG have recently been introduced into practice. Minimal invasive cardiac surgery has been expanding substantially last years because it is associated with reduced postoperative pain, reduced duration of hospital stay and fast recovery and return to work. Retrograde aortic perfusion during minimal invasive cardiac procedures however, may be associated with a higher incidence of neurological complications.34 Patients with severe atherosclerotic disease grade IV or V in the arch or ascending aorta on intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography will be excluded from retrograde aortic perfusion in this study to reduce the risk of cerebral embolic complications. These patients will be switched to central cannulation with antegrade perfusion (right subclavian artery).

Ideally, the neurocognitive outcome of patients undergoing Endo-CABG should be compared with patients undergoing conventional CABG in a randomised controlled trial. This is unfortunately not possible due to the lack of elective conventional CABG surgery in our centre.

In conclusion, the present single-centre prospective observational cohort study may provide information on the risk of poor neurocognitive outcome after Endo-CABG. This information may clarify if theoretical concerns regarding the risk of cerebral embolic complications during retrograde aortic perfusion in patients with mild atherosclerotic disease grades I, II and III are justified or not.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the Limburg Clinical Research Program (LCRP) UHasselt-ZOL-Jessa, supported by the foundation Limburg Sterk Merk, province of Limburg, Flemish government, Hasselt University, Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg and Jessa Hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: FV, JV and BS conceived of the study. KN, FV and BS initiated the study design, and AY, PS, J-PO, JD, JV and LJ helped with implementation. IA provided statistical expertise. All authors contributed to refinement of the study protocol and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of the JESSA Hospital Hasselt.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Likosky DS, Nugent WC, Ross CS. Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Improving outcomes of cardiac surgery through cooperative efforts: the northern new England experience. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2005;9:119–21. 10.1177/108925320500900203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilman S. Cerebral disorders after open-heart operations. N Engl J Med 1965;272:489–98. 10.1056/NEJM196503112721001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jensen BO, Hughes p, Rasmussen LS, et al. . Health-related quality of life following off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting in elderly moderate to high-risk patients: a randomized trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;30:294–9. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newman MF, Grocott HP, Mathew JP, et al. . Report of the substudy assessing the impact of neurocognitive function on quality of life 5 years after cardiac surgery. Stroke 2001;32:2874–81. 10.1161/hs1201.099803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rumsfeld JS, Magid DJ, O’Brien M, et al. . Changes in health-related quality of life following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:2026–32. 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03213-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Furlan AJ, Sila CA, Chimowitz MI, et al. . Neurologic complications related to cardiac surgery. Neurol Clin 1992;10:145–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stamou SC. Stroke and encephalopathy after cardiac surgery: the search for the holy grail. Stroke 2006;37:284–5. 10.1161/01.STR.0000199048.87363.aa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stamou SC, Hill PC, Dangas G, et al. . Stroke after coronary artery bypass: incidence, predictors, and clinical outcome. Stroke 2001;32:1508–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Newman MF. Open heart surgery and cognitive decline. Cleve Clin J Med 2007;74(Suppl 1):S52–5. 10.3949/ccjm.74.Suppl_1.S52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Uysal S, Reich DL. Neurocognitive outcomes of cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2013;27:958–71. 10.1053/j.jvca.2012.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ottens TH, Dieleman JM, Sauer AM, et al. . Effects of dexamethasone on cognitive decline after cardiac surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Anesthesiology 2014;121:492–500. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stygall J, Newman SP, Fitzgerald G, et al. . Cognitive change 5 years after coronary artery bypass surgery. Health Psychol 2003;22:579–86. 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ganushchak YM, Fransen EJ, Visser C, et al. . Neurological complications after coronary artery bypass grafting related to the performance of cardiopulmonary bypass. Chest 2004;125:2196–205. 10.1378/chest.125.6.2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B, et al. . Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2001;344:395–402. 10.1056/NEJM200102083440601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murkin JM, Newman SP, Stump DA, et al. . Statement of consensus on assessment of neurobehavioral outcomes after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;59:1289–95. 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00106-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Powell JB, Cripe LI, Dodrill CB. Assessment of brain impairment with the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test: a comparison with other neuropsychological measures. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 1991;6:241–9. 10.1093/arclin/6.4.241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rudolph JL, Schreiber KA, Culley DJ, et al. . Measurement of post-operative cognitive dysfunction after cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2010;54:663–77. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02236.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Magalhães SS, Malloy-Diniz LF, Hamdan AC. Validity convergent and reliability test-retest of the rey auditory verbal learning test. Clinical Neuropsychiatry 2012;9:129–37. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wagner S, Helmreich I, Dahmen N, et al. . Reliability of three alternate forms of the trail making tests a and B. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2011;26:314–21. 10.1093/arclin/acr024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giovagnoli AR, Del Pesce M, Mascheroni S, et al. . Trail making test: normative values from 287 normal adult controls. Ital J Neurol Sci 1996;17:305–9. 10.1007/BF01997792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang YC, Magasi SR, Bohannon RW, et al. . Assessing dexterity function: a comparison of two alternatives for the NIH Toolbox. J Hand Ther 2011;24 313–21. 10.1016/j.jht.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bastos AG, Gomes BM B. Reliability of the Brazilian WAIS-III in Depression. Interam J Psychol 2001;45:419–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boban M, Malojcic B, Mimica N, et al. . The reliability and validity of the mini-mental state examination in the elderly Croatian population. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2012;33:385–92. 10.1159/000339596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Harten AE, Scheeren TWL, Absalom AR. A review of postoperative cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation associated with cardiac surgery and anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2012;67:280–93. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.07008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chalela JA, Kidwell CS, Nentwich LM, et al. . Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: a prospective comparison. The Lancet 2007;369:293–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60151-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gusmao-Flores D, Salluh JI, Chalhub RÁ, et al. . The confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) and intensive care delirium screening checklist (ICDSC) for the diagnosis of delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Crit Care 2012;16:R115 10.1186/cc11407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guenther U, Popp J, Koecher L, et al. . Validity and reliability of the CAM-ICU Flowsheet to diagnose delirium in surgical ICU patients. J Crit Care 2010;25:144–51. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, et al. . Cognitive trajectories after Postoperative Delirium. N Engl J Med 2012;367:30–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1112923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hudetz JA, Iqbal Z, Gandhi SD, et al. . Postoperative delirium and short-term cognitive dysfunction occur more frequently in patients undergoing valve surgery with or without coronary artery bypass graft surgery compared with coronary artery bypass graft surgery alone: results of a pilot study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2011;25:811–6. 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Plaschke K, Fichtenkamm P, Schramm C, et al. . Early postoperative delirium after open-heart cardiac surgery is associated with decreased bispectral EEG and increased cortisol and interleukin-6. Intensive Care Med 2010;36:2081–9. 10.1007/s00134-010-2004-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McGinn JT, Usman S, Lapierre H, et al. . Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting: dual-center experience in 450 consecutive patients. Circulation 2009;120(11 Suppl):S78–84. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.840041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lapierre H, Chan V, Sohmer B, et al. . Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting via a small thoracotomy versus off-pump: a case-matched study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;40:804–10. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.01.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Poston RS, Tran R, Collins M, et al. . Comparison of economic and patient outcomes with minimally invasive versus traditional off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting techniques. Ann Surg 2008;248:638–46. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818a15b5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Modi P, Chitwood WR. Retrograde femoral arterial perfusion and stroke risk during minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: is there cause for concern? Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:E1 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.11.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. . SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. The Lancet 2007;370:1453–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shiomi H, Morimoto T, Furukawa Y, et al. . Comparison of Five-Year Outcome of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting in Triple-Vessel Coronary Artery Disease (from the Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome Study in Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort-2). Am J Cardiol 2015;116:59–65. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van Agt HM, Essink-Bot ML, Krabbe PF, et al. . Test-retest reliability of health state valuations collected with the EuroQol questionnaire. Soc Sci Med 1994;39:1537–44. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90005-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ren Y, Yang H, Browning C, et al. . Performance of screening tools in detecting major depressive disorder among patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. Med Sci Monit 2015;21:646–53. 10.12659/MSM.892537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Theunissen M, Peters ML, Schouten EG, et al. . Validation of the surgical fear questionnaire in adult patients waiting for elective surgery. PLoS One 2014;9:e100225 10.1371/journal.pone.0100225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sonntag M, Konnopka A, Leichsenring F, et al. . Reliability, validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D in assessing and valuing health status in patients with social phobia. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:215 10.1186/1477-7525-11-215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thombs BD, Hudson M, Schieir O, et al. . Reliability and validity of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:438–43. 10.1002/art.23329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017823supp001.pdf (352.7KB, pdf)