Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between optimal adherence to the first-generation injectable immunomodulatory drugs (IMDs) for multiple sclerosis (MS) and subsequent disability accumulation.

Methods

We accessed prospectively collected linked clinical and administrative health data from British Columbia, Canada. Subjects with MS treated with a first-generation injectable IMD at an MS clinic (1996–2004) were followed until their last clinic visit before 2009. Adherence was estimated using the proportion of days covered (PDC). The primary outcome was disability accumulation, defined as an increase in the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score as recorded during each year of follow-up. Generalised estimating equation models, adjusted for baseline sex, age, EDSS and time between scores, were used to measure associations between optimal adherence (≥80% PDC) during the first year of treatment and subsequent disability accumulation. The relationship between early IMD adherence and the secondary outcome, time to sustained EDSS 6, was examined using Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

Among 801 subjects, 598 (74.7%) had optimal adherence over the first year of IMD treatment and 487 (39.0%) demonstrated one or more instances of disability accumulation. Early optimal adherence was not associated with disability accumulation (adjusted OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.15), nor with time to sustained EDSS 6 (adjusted HR 0.91; 95% CI 0.57 to 1.44).

Conclusion

Almost three-quarters of subjects with MS had optimal early adherence to their first-line injectable IMD. There was no evidence that this was associated with disability accumulation in the following years.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis; adherence, immunomodulatory drugs, disease progression, longitudinal analysis, observational study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

One of the first population-based studies to examine the association between drug adherence and subsequent disability accumulation in multiple sclerosis.

Real-world setting, which increases the generalisability of the study results.

Observational studies cannot adjust or assess all potential (unknown) confounders.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system and is considered one of the most common reasons for non-trauma-related disability in young adults.1 The injectable immunomodulatory drugs (IMDs), beta-interferon and glatiramer acetate, are associated with reduced MS relapse rates in short-term clinical trials,2 but the evidence regarding the effects of these therapies on longer term disability progression drawn from observational studies is mixed.2 3 These drugs are considered first-line therapies in Canada and are commonly used to treat MS worldwide.4

To maximise the potential benefit of any drug, it should be taken as indicated; however, multiple lifestyle, patient-specific and drug-related factors can affect adherence.5 Adherence levels early in treatment predict future adherence patterns.6–8 In general, poor medication adherence is associated with poorer health-related outcomes, including higher risk of morbidity and mortality, increased health services utilisation and increased healthcare costs.9–11 In MS, poor adherence to the IMDs is associated with decreased quality of life, higher relapse rates and higher medical costs.9 12 13 However, to date, the effects of IMD adherence on MS progression are unknown. We examined the association between adherence during the initial year of therapy to a first-line injectable IMD and subsequent disability accumulation in people with relapsing-onset MS in British Columbia (BC), Canada.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This was a retrospective cohort study involving linkage of prospectively collected clinical and administrative health data in BC. The BC Multiple Sclerosis (BCMS) database was the source of the MS cohort. This database, established in 1980, captures detailed clinical information on patients registered at one of the four original MS clinics in BC. The BCMS cohort had previously been linked to BC administrative data to the end of 2008; linkage was complete in 2010, at which time all personal identifiers were removed. Routinely collected data include date of MS symptom onset, disease course at onset (relapsing or primary progressive), and level of disability at the time of each clinical assessment as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS).14

BC’s comprehensive drug database (PharmaNet)15 captures >99% of prescriptions dispensed at outpatient and community pharmacies, with data available since 1 January 1996. The Medical Service Plan database contains physician billing records including dates and diagnostic codes for each patient encounter using the International Classification of Disease (ICD), 9th version, and the Discharge Abstracts Database contains hospital admission and discharge dates,16 17 and diagnosis codes using ICD 9th version (to 2004) or ICD 10th (from 2005) systems. These databases were used to estimate the comorbidity status of patients. The BC Registration and Premium Billing Files,18 which include registration dates in the compulsory provincial healthcare plan, were used to confirm residency during the study period. An estimate of socioeconomic status (SES) was obtained from each individual’s postal code and census-derived neighbourhood income data using an algorithm developed by Statistics Canada.19 A study-specific data set was created by linking the data at the individual level using each person’s unique personal heath number (a lifelong number assigned to every resident of BC). All personal identifiers were removed before data release and analyses.

Study cohort

The study subjects included all persons with MS diagnosed by an MS specialist neurologist20 21 who were registered at a BCMS clinic before 31 December 2004, and received at least one prescription dispensation for a first-line injectable IMD between 1 January 1996 and 31 December 2008 as recorded in the provincial prescription database. The only first-line IMDs available during the study period were interferon-beta-1b, interferon-beta-1a and glatiramer acetate.

Subjects were followed from their index date (date of the first IMD dispensation) until the last recorded EDSS score before the study end date, which was defined as the earlier of start of a non-first-line IMD for MS, entry in an MS drug-related clinical trial or 31 December 2008. Subjects were required to have at least 1 year of residency in BC before the index date (the ‘baseline year’) and 1 year of residency between the index date and study end. Subjects were also required to have at least two recorded EDSS scores: one during the baseline year and one after the first year of IMD therapy. Because the first IMD for MS was approved for use in Canada 1995, virtually all of the included subjects were incident (new) users.

Study exposure and outcome

In the absence of guidelines for how long an individual should remain on an IMD, or prior studies examining adherence and disability progression, we examined adherence during the first year of therapy. Prior studies have suggested that this first year may be clinically relevant, predicting longer term response to the IMDs.22 Adherence was estimated using the proportion of days covered (PDC) measure, calculated as the total number of days of drug dispensed during the 1-year period divided by 365 days.23 All first-line injectable IMDs were considered as one therapeutic group, and switching between these agents was allowed. A PDC of ≥80% indicated ‘optimal’ adherence, and <80% indicated ‘suboptimal’ adherence.24 This threshold was used because it has been associated with health-related outcomes in previous studies, and to allow for comparison with other adherence-related findings.25 26

The outcome of interest was disability accumulation, defined as an increase in the EDSS score of at least:

1.5 points if the reference (prior) EDSS was 027–29

1 EDSS point if the reference (prior) EDSS was ≥1 and <527 28

0.5 point if the reference (prior) EDSS was ≥5.0.27

Each subject’s follow-up period was divided into 1-year intervals. EDSS scores were examined for each 1-year interval (starting during the second year after the index date) to determine if disability accumulation had occurred (categorised as ‘yes or no’) relative to the previous year. The date the EDSS score was recorded within each yearly interval was the ‘outcome date’ for that interval. If multiple EDSS scores were recorded in a single interval, the highest (and earliest in the case of identical scores) was used. If no EDSS score was recorded in the reference interval, the score from the most recent 1-year interval with an available EDSS score was used as the reference (online supplementary figure 1).

bmjopen-2017-018612supp001.pdf (142.5KB, pdf)

Statistical analyses and model adjustment

The association between IMD adherence and subsequent disability accumulation was examined using logistic regression models fitted via generalised estimating equations with an exchangeable working correlation structure.30 IMD adherence was modelled as a binary variable (optimal vs suboptimal). Potential confounders were selected for inclusion in the final models based either on clinical relevance (baseline sex, age and EDSS) or association with the outcome (p≤0.1 from univariate analyses).31 These potential confounders (measured during the baseline year) included all prescriptions dispensed (excluding the MS IMDs), grouped according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System at the fourth level (ie, pharmacological subgroup),32 and categorised as 0–2, 3–4, 5–6 or ≥7, comorbidity status measured using Deyo et al’s adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index33 (categorised as 0 or ≥1), and estimated neighbourhood SES (expressed as quintiles). All models were adjusted for the time between the reference and outcome EDSS score.

Sensitivity and secondary analyses

To fully explore the association between IMD adherence and disability accumulation, we performed several sensitivity analyses and assessed one secondary outcome. For the sensitivity analyses we first measured disability only over the time period that the subject was ‘on drug’, ending follow-up at the last EDSS assessment before the earliest of IMD discontinuation (defined as the first day of >180 days with no exposure to a first-line IMD), initiation of a non-first-line IMD, MS drug clinical trial registration or 31 December 2008. Second, if multiple EDSS scores were recorded in a single 1-year interval, the lowest, rather than highest, score was used as the outcome EDSS. Third, we examined the association between early adherence and disability accumulation in only those subjects with both reference and outcome EDSS scores recorded for every year between the index date and study end date (ie, no EDSS scores were carried forward as reference values). Finally, we examined the association between disability accumulation and adherence, with adherence treated as a continuous variable, categorised into quartiles and using a 90% (instead of 80%) threshold for optimal adherence.

Our secondary study outcome was time to a confirmed and sustained EDSS score of 6.0. This outcome, considered as irreversible disability, was achieved when all subsequent EDSS scores were 6.0 or higher, with at least two records of EDSS 6.0 separated by ≥180 days, as used previously.3 Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the association between IMD adherence and time to sustained EDSS 6.0, adjusted for potential confounders (see online supplementary methods and supplementary figure 1 for additional details).

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) V.21.034 and R V.3.1.2.35

Results

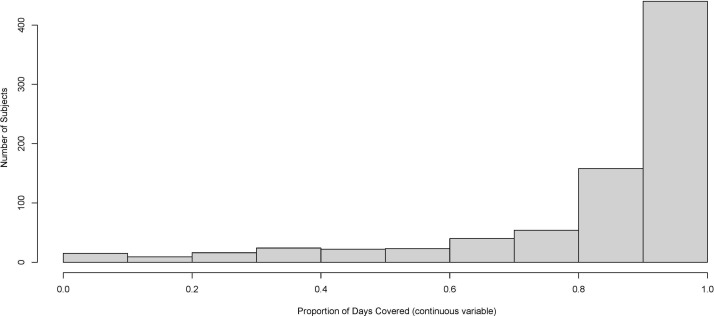

A total of 801 subjects were included in the primary analyses with a mean age of 41.5 years, a mean disease duration of 9.9 years and a median EDSS of 3.0 at the index date. There were a total of 6305 person-years of follow-up (mean of 7.9 (SD: 2.4) years) (table 1). Overall, 598 subjects (74.7%) had optimal adherence during the first year of therapy (figure 1), and 487 (39.0%) met the disability accumulation criterion at least once during follow-up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects included in the primary analysis (n=801)

| Characteristics | Descriptive summaries |

| At the index date (baseline) | |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 192 (24.0) |

| Female | 609 (76.0) |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 41.5 (9.5) |

| Disease duration in years, mean (SD)* | 9.9 (8.3) |

| Initial (index) IMD, n (%) | |

| Beta-interferon | 713 (89.0) |

| Glatiramer acetate | 88 (11.0) |

| During the baseline year | |

| EDSS, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) |

| EDSS, n (%) | |

| ≤3 | 472 (58.9) |

| >3 and ≤5.5 | 201 (25.1) |

| ≥6 | 128 (16.0) |

| Concurrent prescription drug classes, n (%) | |

| 0–2 | 252 (31.5) |

| 3–4 | 194 (24.2) |

| 5-≤6 | 185 (23.1) |

| ≥7 | 170 (21.2) |

| Socioeconomic status, n (%)† | |

| 1 (lowest) | 130 (16.2) |

| 2 | 136 (17.0) |

| 3 | 179 (22.3) |

| 4 | 164 (20.5) |

| 5 (highest) | 168 (21.0) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score, n (%) | |

| 0 | 729 (91.0) |

| ≥1 | 72 (9.0) |

*Disease duration measured from multiple sclerosis symptom onset (recorded in the British Columbia Multiple Sclerosis database) to the index date (missing for five subjects).

†Based on neighbourhood income at index (missing for 19 subjects).

EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale: IMD, immunomodulatory drugs.

Figure 1.

Distribution of adherence.

SES, prescription drug exposure and comorbidity index measures during the baseline year were not significantly associated with subsequent disability accumulation in the univariate analyses and were not included in the multivariable models. After adjustment for baseline sex, age and EDSS, and the amount of time between reference and outcome EDSS scores, there was no evidence of an association between optimal adherence to a first-line injectable IMD during the first year of therapy and subsequent disability accumulation (adjusted OR (adjOR) 0.94; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.15) (table 2). Compared with women, men were at greater risk of disability accumulation over the study period (adjOR 1.28 (1.07 to 1.53) (table 2).

Table 2.

Association between IMD adherence and disability accumulation: results from the generalised estimating equation models (n=801)

| Factors | ORs (95% CIs)* | |

| Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | |

| Level of adherence (PDC) | ||

| Suboptimal (<80%) | 1 | 1 |

| Optimal (≥80%) | 0.94 (0.78 to 1.13) | 0.94 (0.78 to 1.15) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 1.28 (1.07 to 1.52) | 1.28 (1.07 to 1.53) |

| Baseline age, years | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

| Baseline EDSS | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.08) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.08) |

| Time (years) between reference and outcome EDSS | 1.41 (1.30 to 1.55) | 1.42 (1.30 to 1.56) |

*OR >1 indicates an increased likelihood of disability accumulation.

EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; IMD, immunomodulatory drugs; PDC, proportion of days covered.

Findings from the sensitivity and secondary analyses were consistent with those from the primary analyses; optimal adherence was not associated with disability accumulation or time to sustained EDSS 6.0 (adjusted HR 0.91; 95% CI 0.57 to 1.44) (online supplementary tables 1 and 2). There was also no evidence of an association between optimal adherence and disability accumulation when adherence was included in the models as a continuous variable, categorised into quartiles, or with a 90% threshold for optimal adherence (results not shown).

Discussion

In this MS cohort, nearly three-quarters of the subjects demonstrated optimal adherence during the first year of using a first-line injectable IMD therapy. We did not observe a difference in the odds of disability accumulation for those with optimal IMD adherence in the first year of therapy compared with those with suboptimal adherence. Similarly, no difference was observed when disability was assessed as the time to the sustained milestone, EDSS 6.0.

Most individuals in our cohort were found to have optimal adherence, which is similar to adherence levels reported in previous studies.12 36 For instance, a study that examined adherence during the first year of IMD therapy in 2446 patients with MS covered by commercial health plans in the USA reported that 60% of the cohort had optimal (≥80%) adherence.9 Another recent study examined adherence in 4830 individuals with MS using health administrative data from three provinces in Canada (which included BC). Optimal adherence (≥80%) was achieved in 76% of subjects during the first year of therapy.36

Previous studies have reported on the effects of IMD adherence on the quality of life of patients with MS,10 medical care costs9 and relapse risk,37 but to our knowledge no study has examined the association between IMD adherence and disability accumulation. We did not observe positive effects of IMD adherence on disability. As it is known that not all individuals respond to beta-interferon or glatiramer acetate therapy, one potential explanation for this null finding could be that optimal adherence is only associated with beneficial effects within certain subgroups of people with MS. Alternatively, while the first-line injectable IMDs have demonstrated modest effects on disability accumulation over the short term in clinical trials,2 38 it is possible that this effect does not translate into long-term benefits in real-world clinical practice. Although it is not known how long a person should be on an IMD before gaining benefit, assessment of adherence over the first year may be insufficient, and may miss non-adherence that occurs after the first year, due to needle fatigue for example.39 We specifically assessed adherence in the first year for a number of reasons. First, others have shown that this initial window may be of clinical relevance, predicting future response.22 Second, this method facilitated a degree of separation between the exposure (adherence) and outcome (disability accumulation). Finally, previous studies have shown that early adherence after drug initiation is predictive of later adherence in some chronic conditions, including MS.6–8 One recent study from an American-managed care program database found that adherence over the 1-year period immediately following IMD initiation predicted adherence over the subsequent year.6 Similarly, adherence to statins during the first 4 months after therapy initiation was shown to predict adherence over the subsequent year in a large North American population.7

A major strength of this study is the use of a representative sample of individuals with MS in the ‘real-world’ setting. Although findings from the short-term clinical trials of the first-generation IMDs demonstrated modest effects on disability accumulation, clinical trials tend to enrol participants who are highly selected in terms of age, comorbidities and motivation, and employ strict protocols for clinical monitoring to prevent or mitigate severe adverse events. Thus, trial participants may not be fully representative of those treated in clinical practice, such that data on effectiveness and adherence derived from clinical trial participants may not be generalisable to the wider MS population. Further strengths include study outcomes (EDSS scores) that were assigned by the treating MS neurologists during clinic visits and captured prospectively. Also, our use of prescription dispensations from administrative data to estimate adherence eliminated the potential for recall bias. Finally, to test the robustness of our main findings, we examined the association between IMD adherence and disability accumulation using a variety of approaches, including a secondary (alternative) outcome and different methods of categorising adherence. All of the findings from these sensitivity analyses confirmed that there was no evidence of an association between optimal IMD adherence during the first treatment year and subsequent disability accumulation.

There are limitations that should be noted. We cannot be certain that a patient who received a dispensation for an IMD actually administered the drug. However, given the high cost of IMDs, the number of patients who actively filled repeated prescriptions for their medications but did not use them is assumed to be negligible. As with all observational studies, we were not able to assess all potential confounders; our data did not include information on lifestyle, such as smoking status or diet, both of which could be associated with IMD adherence and disability accumulation.40 41 However, we were able to account for disability level and comorbidity burden at baseline, both of which have been linked to IMD adherence and subsequent MS disability accumulation in previous studies.41 Finally, we used the EDSS to measure disability accumulation. While this is a routine clinical measure and the most widely used and internationally recognised disability assessment tool in MS, it is heavily influenced by ambulation and does not adequately capture other common MS symptoms such as cognitive deficits and fatigue.

This is the first study to examine the impact of adherence to the first-line injectable IMDs on disability accumulation in MS. Among a cohort of incident users of first-line injectable IMDs, we were unable to find evidence that individuals with MS with optimal adherence during the first year of therapy were at lower odds of disability accumulation compared with those with suboptimal adherence. However, it remains possible that optimal adherence to IMDs positively affects other important outcomes for people with MS that were not considered here, such as quality of life and employment status. Further research examining other relevant MS-related outcomes is needed to fully understand the impact of IMD adherence in MS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the BC Ministry of Health, BC Vital Statistics Agency and BC PharmaNet for approval and support with accessing provincial data; and Population Data BC for facilitating approval and use of the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: CE and TZ had access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analyses. CE, EK, HT, FZ and TZ designed the study, and CE, HT and RAM obtained funding. TZ and FZ performed the statistical analyses. TZ drafted the manuscript. EK, FZ, JP, RAM, LFK, HT and CE were involved with the interpretation of the data and critically revising the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version to be published.

Funding: This study was funded by a National Multiple Sclerosis Society Operating Grant (RG-4757-A-3). Dr Zhang received a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada. The study sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of results, writing of this manuscript or decision to submit.

Disclaimer: All inferences, opinions and conclusions drawn in this study are those of the authors and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Data Steward(s).

Competing interests: TZ, EK and FZ declare no conflicts. JP holds research funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and over the past 3 years has received consulting fees or fees for service on Data Safety Monitoring Boards from the Canadian Study Group on CCSVI, EMD Serono, Novartis and Teva Pharmaceuticals Europe. LFK has received honoraria or consultation fees from Bayer Healthcare, Biogen Idec, EMD Canada, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, Hoffmann La-Roche and Teva Canada, and unrestricted travel grants to attend scientific meetings including the American Academy of Neurology, American Neurological Association, Neuroscience, ECTRIMS, ISNI, and IHW from Bayer Healthcare, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono, Hoffmann La-Roche, Novartis and Teva Canada. RAM receives research funding from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Research Manitoba, Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada, Multiple Sclerosis Scientific Foundation, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Rx&D Health Research Foundation, Crohn’s and Colitis Canada and the Consortium of MS Centers, and has conducted clinical trials funded by Sanofi-Aventis. HT is the Canada Research Chair for Neuroepidemiology and Multiple Sclerosis. She currently receives research support from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada and the Multiple Sclerosis Scientific Research Foundation. In addition, in the last 5 years she has received research support from the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada (Don Paty Career Development Award); the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (Scholar Award) and the UK MS Trust; speaker honoraria and/or travel expenses to attend conferences from the Consortium of MS Centers (2013), the National MS Society (2012, 2014, 2016), ECTRIMS (2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016), the Chesapeake Health Education Program, US Veterans Affairs (2012), Novartis Canada (2012), Biogen Idec (2014) and American Academy of Neurology (2013, 2014, 2015, 2016). All speaker honoraria are either declined or donated to an MS charity or to an unrestricted grant for use by her research group. CE declares no conflicts.

Ethics approval: University of British Columbia Clinical Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Privacy legislation and policies of the British Columbia Ministry of Health prevent the sharing of data.

References

- 1. Leary SM, Porter B, Thompson AJ. Multiple sclerosis: diagnosis and the management of acute relapses. Postgrad Med J 2005;81:302–8. 10.1136/pgmj.2004.029413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Filippini G, Del Giovane C, Vacchi L, et al. . Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD008933 10.1002/14651858.CD008933.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shirani A, Zhao Y, Karim ME, et al. . Association between use of interferon beta and progression of disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. JAMA 2012;308:247–56. 10.1001/jama.2012.7625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atlas of MS. Mapping multiple sclerosis around the world. 2013. https://www.msif.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Atlas-of-MS.pdf (accessed 16 June 2017).

- 5. Jimmy B, Jose J. Patient medication adherence: measures in daily practice. Oman Med J 2011;26:155–9. 10.5001/omj.2011.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kozma CM, Phillips AL, Meletiche DM. Use of an early disease-modifying drug adherence measure to predict future adherence in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:800–7. 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.8.800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Franklin JM, Krumme AA, Shrank WH, et al. . Predicting adherence trajectory using initial patterns of medication filling. Am J Manag Care 2015;21:e537–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Franklin JM, Shrank WH, Lii J, et al. . Observing versus Predicting: Initial Patterns of Filling Predict Long-Term Adherence More Accurately Than High-Dimensional Modeling Techniques. Health Serv Res 2016;51:220–39. 10.1111/1475-6773.12310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tan H, Cai Q, Agarwal S, et al. . Impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther 2011;28:51–61. 10.1007/s12325-010-0093-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim S, Shin DW, Yun JM, et al. . Medication Adherence and the Risk of Cardiovascular Mortality and Hospitalization Among Patients With Newly Prescribed Antihypertensive Medications. Hypertension 2016;67:506–12. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krivoy A, Balicer RD, Feldman B, et al. . Adherence to antidepressant therapy and mortality rates in ischaemic heart disease: cohort study. Br J Psychiatry 2015;206:297–301. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.155820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Menzin J, Caon C, Nichols C, et al. . Narrative review of the literature on adherence to disease-modifying therapies among patients with multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19:S24–40. 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.s1.S24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, Macdonell R, et al. . The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2011;18:69–77. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983;33:1444–52. 10.1212/WNL.33.11.1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. BC Ministry of Health [creator]. PharmaNet. V2. BC Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. Data Stewardship Committee [online], 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data (accessed 17 June 2017).

- 16. Canadian Institute for Health Information [creator]. Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract [online]. MOH 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data (accessed 15 June 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 17. British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]. Medical Services Plan (MSP) Payment Information File. V2. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract [online]. MOH 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data (accessed 15 June 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18. British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator]. Consolidation File (MSP Registration & Premium Billing). V2. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract [online]. MOH 2012. http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data (accessed 17 June 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilkins R, Berthelot JM, Ng E. Trends in mortality by neighbourhood income in urban Canada from 1971 to 1996. Health Rep 2002;13:1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Poser CM, Paty DW, Scheinberg L, et al. . New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols. Ann Neurol 1983;13:227–31. 10.1002/ana.410130302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. . Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2001;50:121–7. 10.1002/ana.1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Río J, Castilló J, Rovira A, et al. . Measures in the first year of therapy predict the response to interferon beta in MS. Mult Scler 2009;15:848–53. 10.1177/1352458509104591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation 2009;119:3028–35. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Winkelmayer WC, Levin R, Setoguchi S. Associations of kidney function with cardiovascular medication use after myocardial infarction. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:1415–22. 10.2215/CJN.02010408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487–97. 10.1056/NEJMra050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, et al. . Good and poor adherence: optimal cut-point for adherence measures using administrative claims data. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2303–10. 10.1185/03007990903126833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giovannoni G, Cook S, Rammohan K, et al. . Sustained disease-activity-free status in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine tablets in the CLARITY study: a post-hoc and subgroup analysis. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:329–37. 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70023-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Havrdova E, Galetta S, Hutchinson M, et al. . Effect of natalizumab on clinical and radiological disease activity in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective analysis of the Natalizumab Safety and Efficacy in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (AFFIRM) study. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:254–60. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70021-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rotstein DL, Healy BC, Malik MT, et al. . Evaluation of no evidence of disease activity in a 7-year longitudinal multiple sclerosis cohort. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:152–8. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MD, et al. . Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:364–75. 10.1093/aje/kwf215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hosmer D, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant R. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd ed New York: Wiley, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2013 [online]. Oslo 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–9. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. [online]. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; (accessed 29 Jan 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 35. Core Team R. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2016. http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed 29 Jan 2016).

- 36. Evans C, Marrie RA, Zhu F, et al. . Adherence and persistence to drug therapies for multiple sclerosis: A population-based study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016;8:78–85. 10.1016/j.msard.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Steinberg SC, Faris RJ, Chang CF, et al. . Impact of adherence to interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a non-experimental, retrospective, cohort study. Clin Drug Investig 2010;30:89–100. 10.2165/11533330-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tramacere I, Del Giovane C, Salanti G, et al. . Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD011381 10.1002/14651858.CD011381.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Remington G, Rodriguez Y, Logan D, et al. . Facilitating medication adherence in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2013;15:36–45. 10.7224/1537-2073.2011-038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McKay KA, Tremlett H, Patten SB, et al. . Determinants of non-adherence to disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: A cross-Canada prospective study. Mult Scler 2017;23:588–96. 10.1177/1352458516657440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McKay KA, Jahanfar S, Duggan T, et al. . Factors associated with onset, relapses or progression in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Neurotoxicology 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018612supp001.pdf (142.5KB, pdf)