Abstract

Objectives

Patients with advanced disease sometimes express a wish to hasten death (WTHD). In 2012, we published a systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative studies examining the experience and meaning of this phenomenon. Since then, new studies eligible for inclusion have been reported, including in Europe, a region not previously featured, and specifically in countries with different legal frameworks for euthanasia and assisted suicide. The aim of the present study was to update our previous review by including new research and to conduct a new analysis of available data on this topic.

Setting

Eligible studies originated from Australia, Canada, China, Germany, The Netherlands, Switzerland, Thailand and USA.

Participants

Studies of patients with life-threatening conditions that had expressed the WTHD.

Design

The search strategy combined subject terms with free-text searching of PubMed MEDLINE, Web of Science, CINAHL and PsycInfo. The qualitative synthesis followed the methodology described by Noblit and Hare, using the ‘adding to and revising the original’ model for updating a meta-ethnography, proposed by France et al. Quality assessment was done using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist.

Results

14 studies involving 255 participants with life-threatening illnesses were identified. Five themes emerged from the analysis: suffering (overarching theme), reasons for and meanings and functions of the WTHD and the experience of a timeline towards dying and death. In the context of advanced disease, the WTHD emerges as a reaction to physical, psychological, social and existential suffering, all of which impacts on the patient’s sense of self, of dignity and meaning in life.

Conclusions

The WTHD can hold different meanings for each individual—serving functions other than to communicate a genuine wish to die. Understanding the reasons for, and meanings and functions of, the WTHD is crucial for drawing up and implementing care plans to meet the needs of individual patients.

Keywords: Palliative Care, qualitative research, medical ethics, oncology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This updated review and synthesis of the published literature on the wish to hasten death (WTHD) offers a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon.

The review provides meta-ethnographic analysis of the 14 studies that recorded the experiences of 255 participants from different cultural backgrounds including Australia, Canada, China, Germany, Switzerland, Thailand, The Netherlands and the USA.

This synthesis highlights suffering as an overarching theme and includes physical, psychological, social or existential factors.

The synthesis exemplifies a new approach to the updating of syntheses of qualitative research.

Included studies offer different conceptualisations of the WTHD with the research objectives of some studies only touching indirectly on the phenomenon.

Introduction

Few issues in modern society generate as much controversy as euthanasia and assisted suicide (EAS) among people facing an advanced illness. Across the world, opinions and attitudes towards this issue differ widely. Debate, however, often centres around the implications for society or the existing legal framework. What is often overlooked is the common thread that links all those persons who contemplate ending their life: the desire to die or to hasten their death. Why do some patients with advanced disease wish to hasten their death? What meaning does this wish hold for them? What is the experience of a person who feels such a wish? To what extent do commonalities exist among those who come to feel this wish?

Although the desire to die has traditionally been seen to result from physical suffering, research suggests that this explanation is reductionist1 and that such a wish must be understood in the context of patient experience. Thus, while cross-sectional studies offer valuable information about what may trigger a wish to die, the fluctuating, ambivalent, subjective and complex nature of such wishes requires a more detailed examination of patients’ experiences.

Several qualitative studies have explored the wish to die in patients with advanced disease highlighting the important role played by psychosocial and existential/spiritual factors, alongside physical symptoms.2 3 Thus, factors such as loss of self, loss of the sense of dignity, loss of autonomy, fear about the future, fear of suffering and fear of being a burden to others are reported among the main triggers of a wish to hasten death (WTHD). Interpretative analysis of the WTHD suggests that, in addition to these potential motivations, attention must focus on the meanings, functions and intentions that underlie the expression of a WTHD. Thus, if we are to understand what patients actually mean when they say that they ‘no longer wish to live in this way’, we must explore their personal history, attitudes, beliefs and thoughts. Furthermore, it is important not to confuse, for example, a wish to die in someone who is not considering actually hastening his/her death with a will to die in someone who takes action towards dying.4

In 2012, our group published a systematic review and interpretative synthesis5 of then-published qualitative studies of the WTHD in seeking to understand the experience of patients with serious or incurable illness who expressed such a wish. The synthesis included studies conducted in Canada,1 6 Australia,2 China7 and the USA.8 At that time, however, no such studies were identified from European countries.

Five years on, the subsequent publication of qualitative studies of the WTHD, among similar patient groups, and in different contexts to those featured in our earlier synthesis, justifies the need for an updated systematic review. In addition, the possibility of including studies from European countries in which EAS has been decriminalised4 9–11 enables us to explore the extent to which different legal contexts influence the expression of a WTHD. The aim of the present study was therefore to provide an updated review of knowledge regarding the WTHD (understood here as any expression of the desire to die in patients affected by a life-threatening condition), taking into account possible contextual differences.

Methods

This systematic review and interpretative synthesis updates our previous synthesis5 that included studies from 2001 to January 2010. In seeking to incorporate recent research within the synthesis, we extended our bibliographic search to cover the period from December 2000 to January 2016. The update employs Noblit and Hare’s12 meta-ethnography method, the aim of which is ‘to compare, re-interpret, and synthesise the findings (ie, authors’ concepts and themes) of separate qualitative studies to arrive at an exhaustive description of the range, nature, and variety of patients’ experiences’.13 This method was chosen given its widespread use in health-related research.14

France et al15 propose various models for updating meta-ethnographies, using the analogy of house-building. This review applies the model they refer to as ‘extending and renovating the original house’ (ie, adding to and revising an existing meta-ethnography). France et al15 outline potential advantages of using this model: the output forms a single coherent model or set of findings, rather than two, to increase its potential usefulness; it can lead to new conceptual insights; and it allows for innovation within the updated analysis/synthesis, while making efficient use of resources expended on the original meta-ethnography.

Data sources and search strategy

In seeking recent clinical evidence about the WTHD, we revised our original search strategy to optimise the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity (see table 1). Relevant MeSH and free-text terms were identified and combined. The strategy was run in PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science and PsycINFO with the terminology being adapted to each database.

Table 1.

Final database search strategy

| 1 | Desire to hasten death |

| 2 | Wish to hasten death |

| 3 | Euthanasia (MeSH) |

| 4 | Suicide, assisted (MeSH) |

| 5 | End-of-life decisions |

| 6 | Wish to die |

| 7 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 |

| 9 | Palliative care |

| 10 | End of life care |

| 11 | End of life |

| 12 | 9 or 10 |

| 13 | Chronic disease |

| 14 | Chronic illness |

| 15 | Advanced disease |

| 16 | Advanced illness |

| 17 | Advanced cancer |

| 18 | Life-limiting illness |

| 19 | Terminally ill |

| 20 | Life-threatening illness |

| 21 | Life-threatening condition |

| 22 | 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 |

| 23 | Qualitative PubMed or CINAHL filter |

| 25 | 7 and 12 and 22 |

| 26 | 25 and 23 |

| 27 | 26 not (child*) or (pediatr*) |

A filter for qualitative studies was used in PubMed,16 CINAHL17 and PsycINFO.18 The qualitative PubMed filter was adapted to the specific language used by Web of Science.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included, papers had to report primary qualitative studies (ie, studies using recognised methods of both qualitative data collection and qualitative data analysis) written in English and focusing on the expression of the WTHD in patients with life-threatening conditions. Paediatric populations were excluded, as were studies focusing on older populations in the absence of advanced disease.

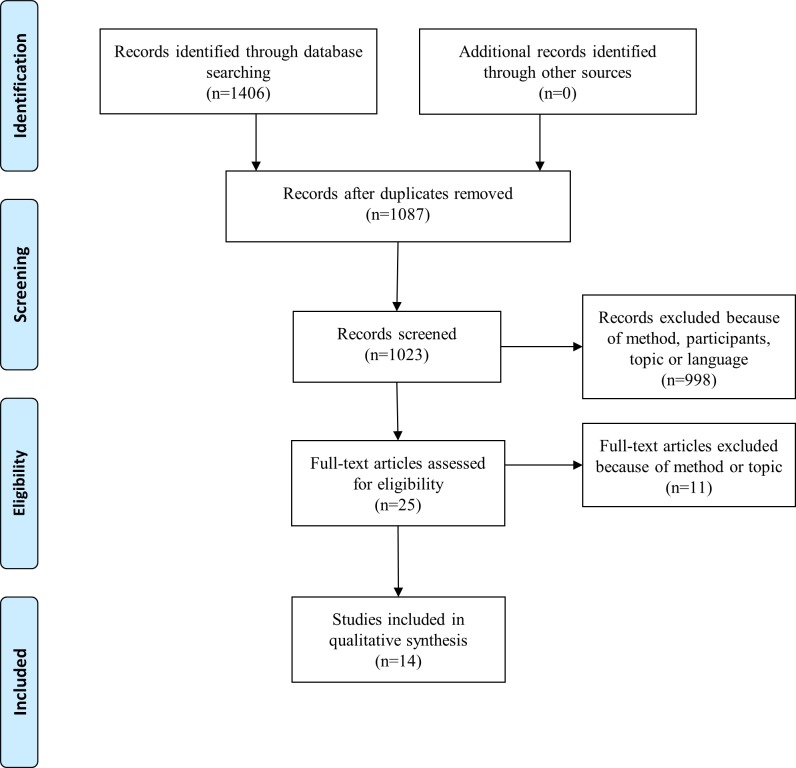

One researcher carried out the systematic literature search, which was verified by another researcher. Screening involved selection of retrieved citations by title, abstract and full text. The entire sample was double-reviewed. Disagreements were resolved by discussion within the research team. Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis flow chart for the selection of studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

Critical appraisal

Included studies were assessed for methodological quality and rigour using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme guidelines for qualitative studies19 (online supplementary table 1). No studies were excluded from this review based on their quality.

bmjopen-2017-016659supp001.pdf (503.1KB, pdf)

Data analysis and synthesis

The synthesis followed the seven steps proposed by Noblit and Hare12 as follows:

Definition of the research question: what is the experience of the WTHD expressed by people with advanced illness?

A literature search for references to studies for inclusion in the synthesis.

Reading the studies in order to identify key and secondary concepts in each of them.

Determining how the studies are related. To this end we created a chart showing the categories that emerged from the studies (more descriptive level), and this served as the basis for abstracting themes and subthemes from each study (more abstract levels that encapsulate the categories found in the different studies).

To perform translation across studies, in other words, to ‘deconstruct’ the studies, identifying different metaphors or concepts on the basis of words or statements in the original articles.

These translations were synthesised to generate different levels of themes, subthemes and final categories.

Presentation of the synthesis of the studies was included, thus giving rise to a global understanding of the phenomenon and a response to the research question posed at the outset.

Online supplementary table 2 juxtaposes the steps from the previous meta-ethnography and the updated meta-ethnography, and online supplementary table 3 shows the comparison of yield between the original review and the updated review. Atlas.ti V.7 software was used to code and memo significant statements to facilitate comparison of the themes and categories obtained by each researcher.

Results

Fourteen articles were included in the updated meta-ethnography (seven from the original synthesis (2001-January 2010) plus seven additional recent studies (2010–February 2016)) (table 2). Of the seven new studies included, six were conducted in European settings4 9–11 20 21 and one in Asia.22

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included in the present review

| Source paper | Country | Participants | Setting | Country’s legislation on EAS |

| Lavery et al1 | Canada | 31 men; 1 woman with HIV/AIDS | HIV Ontario Observational Database | Neither euthanasia nor AS are legal |

| Kelly et al2 | Australia | 30 terminally ill cancer patients | Inpatient hospice unit and home PC service | |

| Coyle and Sculco24 | USA | 7 terminally ill cancer patients | Pain and PC unit in an urban cancer research centre | |

| Mak and Elwyn7 | China | 6 patients | 26-bed hospice in China | |

| Pearlman et al23 | USA | 35 patients | Patient advocacy organisations that counsel persons interested in AS, hospices and grief counsellors | AS legal since 2009. At the time of the study, AS had yet to be decriminalised |

| Schroepfer8 | 18 terminally ill elders | 2 PC programmes, 2 hospital outpatient clinics and six hospices | Neither euthanasia nor AS are legal | |

| Nissim et al6 | Canada | 27 ambulatory cancer patients | Outpatient clinics at a large cancer centre | |

| Stiel et al20 | Germany | 10 inpatients and 2 outpatients of PMD | PMD of three university hospitals | |

| Dees et al9 | The Netherlands | 31 patients with different diagnoses | Support and Consultation on Euthanasia in The Netherlands network; hospice, hospital and nursing home | EAS legal since 2009 |

| Ohnsorge et al10 | Switzerland | 2 women with terminal cancer, and caregivers | PC hospice | AS legal since 1942 |

| Ohnsorge et al11 | 30 terminally ill cancer inpatients/outpatients and their caregivers/relatives | Hospice, a PC ward in the oncology department of a general hospital and an ambulatory PC service | ||

| Ohnsorge et al4 | 30 terminally ill cancer inpatients/outpatients and their caregivers/relatives | Hospice, a PC ward in the oncology department of a general hospital and an ambulatory PC service | ||

| Nilmanat et al22 | Thailand | 11 women and 4 men with terminal cancer and short-life expectancy | Public health service for cancer treatment | Neither euthanasia nor AS are legal |

| Pestinger et al21 | Germany | 10 inpatients and 2 outpatients of PMD | PMD of three university hospitals |

AS, assisted suicide; EAS, euthanisia and assisted suicide; PC, palliative care;

PMD, palliative medicine department.

Three studies used grounded theory,1 6 20 with a further study using a modified approach.21 One was a mixed-method study,2 from which only the qualitative results were included in the present analysis. One study reported using a phenomenological approach,2 and three studies reported using a combination of phenomenological and hermeneutical methods.4 7 11 A hermeneutical-ethical approach was applied in one study.10 The design of one qualitative study was unclear (not specified).22 Most studies used in-depth or semistructured interviews to collect data, except for one that used narrative interviews.10 Sample sizes ranged from 2 to 35 participants, yielding a total sample of 255 patients (excluding the relatives interviewed in one study23). The majority of studies aimed to explore the WTHD as expressed by patients with advanced disease. Only two studies had the main objective of describing suffering.9 22

Description of themes

Five main themes emerged from the analysis of the WTHD expressed by patients with advanced disease: suffering, which appeared as an overarching theme; reasons for the WTHD; meanings of the WTHD; functions of the WTHD; and lived experience of a timeline towards dying and death. Online supplementary table 4 shows the most representative statements for each theme together with its corresponding subthemes.

The greater detail offered by the seven recent studies enabled the six themes from our previous meta-ethnography5 to be subsumed under new, broader categories without substantially changing their content (table 3). One new theme emerged from the present analysis: lived experience of a timeline towards dying and death. Table 4 shows which themes and subthemes were present in each included study.

Table 3.

Reclassification of themes from the original meta-ethnography in the present, updated meta-ethnography

| Themes from the original meta-ethnography5 | Themes in the updated meta-ethnography | |

| WTHD in response to physical/psychological/spiritual suffering | Reasons for the WTHD | Suffering |

| Loss of self | ||

| Fear | ||

| WTHD as a desire to live but ‘not in this way’ | Meanings of the WTHD | |

| WTHD as a way of ending suffering | ||

| WTHD as a kind of control over life: ‘to have an ace up one’s sleeve just in case’ | Functions of the WTHD | |

| Lived experience of a timeline towards dying and death | ||

WTHD, wish to hasten death.

Table 4.

Themes and subthemes present in each of the studies included in this review

| Lavery et al1 | Kelly et al2 | Coyle and Sculco24 | Mak and Elwyn7 | Pearlman et al23 | Schroepfer8 | Nissim et al6 | Stiel et al20 | Dees et al9 | Ohnsorge et al10 | Ohnsorge et al11 | Ohnsorge et al4 | Nilmanat et al22 | Pestinger et al21 | |

| Suffering | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Reasons for the WTHD | ||||||||||||||

| Physical factors | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Psychological factors | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Social factors | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Loss of self | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Meanings of the WTHD | ||||||||||||||

| Cry for help | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| To end suffering | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| To spare others from the burden of oneself | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| To preserve self-determination to the very end | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Will to live but not in this way | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | |

| Functions of the WTHD | ||||||||||||||

| WTHD as a means of communicating | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ✓ | – | – | |

| WTHD as a form of control | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lived experience of a timeline towards dying and death | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

WTHD, wish to hasten death.

Suffering

Suffering emerged as an overarching theme, confirming that the WTHD in people with advanced disease cannot be understood without taking their suffering into account. As a theme, suffering referred not only to physical distress (especially pain) but also to psychological, social or existential aspects. Thus, suffering was a complex and multidimensional phenomenon affecting the whole person, having physical repercussions and impacting both on their identity and their relationships with all aspects of their immediate environment. Suffering was a common denominator for understanding the other four themes: reasons, meanings, functions and lived experience of a timeline towards dying and death.

To have pain and also breathlessness, that would be terrible and so much suffering. My breathing is suffering and this affects my appetite. So many kinds of suffering… The social situation is suffering….7

Reasons for the WTHD

This theme refers to the factors or rational motivations that led to a WTHD being expressed. As in our previous review,5 the WTHD emerged as a complex reaction to suffering that was related to all dimensions of personhood. Our analysis indicated that the theme reasons could be broken down into four subthemes: physical, psychological/emotional and social factors and the loss of self.

Physical factors

In all the studies reviewed, physical factors (symptoms) were a key issue leading to the WTHD. Participants particularly emphasised a loss of function and pain, although aspects such as fatigue, dyspnoea, incontinence and cognitive impairments were also mentioned as producing considerable distress.1 4 9 23

Most participants referred to the loss of physical function; their illness prevented them from doing the things they once did, stripping them of their independence: ‘I lost my dignity, lying in bed in diapers, I am no longer the independent person I used to be’.9 The loss of function was also linked to a diminished quality of life.

Many patients described severe and unbearable pain as a factor that triggered a WTHD. Pain ‘affected the wholeness of their beings’,22 and their lived experience: ‘pain affects everything. It makes you tired. It affects how you can eat. It affects other people, and the fact is that even if you try to hide it, you can’t. […] pain takes that life out of you’. Some patients experienced intense and uncontrollable pain but stated that were it not for this they would want to go on living: ‘It is torturous… thinking when I am going to die to escape from this suffering. But when I am not in pain, I want to live. When the symptoms disappear, I want to continue living, as I do not want to depart from my loved ones’.22 Likewise, some participants9 stated that their request for euthanasia stemmed from the continuous pain they suffered. In many cases, they feared becoming a burden on others and making them suffer. For others, however, it was linked to a loss of control over their illness (due to ineffective medical treatment) and to a feeling of helplessness to the sense that nothing could remedy their situation.

Psychological/emotional factors

This subtheme comprised two categories: fear and hopelessness. Fear was expressed in most interview studies, encapsulating fear due to uncertainty, fear about future suffering and fear of the dying process.

Fear due to uncertainty was linked to inadequate knowledge about prognosis and to not knowing what lay ahead. In most cases, fear was associated with a loss of control over bodily functions and over one’s life and circumstances, as well as with physical, and functional decline, and the thought of becoming a burden on family.

Many patients, aware of their progressive deterioration, foresaw a death that would be painful both for them and their relatives, and hence they experienced a fear about future suffering. The experience of pain and distress, combined with a loss of function, led some to expect an unbearable suffering ‘worse than death itself’.9 21 23 24 In some interviews, pain or suffering was explicitly mentioned as ‘the biggest fear’.24 Some reported that they would rather die than suffer further pain of the kind they had already experienced.

The fear of the dying process resulted from patients’ expectation that they would be unable to express their needs, wishes or problems due to frailty or cognitive impairment.21 This fear was linked to not knowing whether the future would be marked by intense suffering.

The sense of hopelessness felt by patients was associated with the progressive nature of their illness, a process that would lead inevitably to death, and about which nothing could be done: ‘You lie in bed and none of the normal functions come back. They will never come back and it will only get worse’.9 Some patients said they felt mentally exhausted and tired of fighting their illness. One of the interviewees described his illness as ‘the end of many dreams for plans […] the end of it all. There’s no future really’.2

Social factors

For many, social factors, such as being a burden on others, making loved ones suffer, or being dependent, and in need of help, were another cause of suffering and a reason for expressing the WTHD. The idea of causing others to suffer frequently caused patients themselves to suffer. For some, observing their own deterioration and the impact of this on loved ones, was more difficult to bear than their own suffering.

Related to loss of function was increased dependency on others resulting from a deteriorating state. In some cases, this dependency left many patients ‘at the mercy of others’9 and feeling useless. Participants complained about needing to be fed, washed or dressed by others1 7: ‘It’s horrible […] the whole situation. […] Not being able to get out of it, and every morning the same thing: waking up, being washed, lying there till the evening, the same pain’.4 For those who had been highly independent prior to their illness, or who had a high level of professional responsibility at work, the change in role (ie, to dependency and vulnerability) impacted enormously on their way of life, with some finding this difficult to accept.

Some patients said that they felt devalued and treated as if they were no longer a person. Thus, further suffering and a loss of self-esteem could be caused by health professionals failing to respond to their needs, to convey empathy and a comforting attitude or to respect their treatment choices.4

Just one sentence can hurt me, making things even worse… Really bad… When I need someone to help me, they just hurt my self-esteem […] I was right but they said I was wrong… What was worst was that I had to admit to being wrong and agree with them.7

Loss of self

Many participants attributed the WTHD to a perceived loss of self or of identity, due to the impact of their illness on their life. Physical, psychological and social factors (suffering; dependency; loss of control, both mentally and physically; loss of self-esteem; or feeling a burden on others and so on) combined to severely undermine their self-image and their sense of who they were: ‘she was going to lose significant ability to be the person she was’.23 Some studies referred to the loss of self as a loss of the essence, loss of personality, loss of the sense of dignity23 or destruction of the self.24 When participants felt vulnerable, looked down on or inferior with respect to others, then the loss of self was heightened. In some cases, this led the individual to feel a loss of community,1 that is, a loss of close personal relationships accompanied by feelings of isolation, and a lack of understanding.

Many patients described the experience of being devalued or treated as an object, as well as the feeling of having lost control over oneself and of being forced into a situation that went against all they considered to be important, as losing their sense of dignity. Some situations—especially those that drew attention to their loss of control and independence, notably in hospital settings—were perceived by interviewees as demeaning, leading them to being felt treated as objects or patients rather than as individuals.1 23

Some patients did not wish to succumb to a situation over which they had little control, and thus the WTHD emerged in response to a perceived lack of purpose or meaning in life: ‘I’m just saying to myself when I go to sleep, ‘Just let me die.’ I don’t want to have to wake up and face this. […] I have nothing to live for, absolutely nothing. There’s nothing coming up in my life that I am living towards, and if there was it would be so terrible because it probably wouldn’t happen’.6 For patients such as this, losing what made life worthwhile and relevant strips them of the will to live. This loss of self is associated with a broader series of losses (of quality of life, of autonomy, of the ability to perform daily life activities and so on), such that illness is experienced as progressive loss that will cease only in death.

Meanings of the WTHD

Our analysis suggested that the meanings attributed by patients to the WTHD could be categorised into five subthemes.

Cry for help

As a result of their suffering, many participants expressed the need for immediate action to put an end to their torture and to the misery of the current situation.24 In some cases, this involved an explicit request for help—whether from professionals or someone close to them—in coping with all they were going through. For other patients, the cry of despair was the result of their suffering and the difficulty of accepting their illness, an aspect revealed in the rhetorical questions that are sometimes posed: ‘Why me?’ or ‘Why do I have to go through this?’.22 24

To end suffering

Death was sometimes described as preferable to suffering, or as the lesser of two evils4 (‘I don’t want to go through the dying process so I’ll kill myself’24). Here, the WTHD becomes synonymous with not wanting to suffer any more, and the desired death is seen as a release (‘a vehicle to just, just stop my life’24), as a way of putting an end to loneliness, fear, dependence, pain, hopelessness and the feeling that life is no longer enjoyable,8 or as a means of limiting disintegration and loss of self.1

To spare others from the burden of oneself

Advanced illness and its consequences (ie, suffering, loss of independence and the need for help from others) led some people to state that they would rather die than be a burden to their loved ones or see them suffer: ‘No matter how much they love you, you are always a burden. You automatically become a burden to everyone…’6; ‘When I know that my life has become a burden to my loved ones, I would rather die’.22 The WTHD can thus represent the desire to spare others from suffering, a gesture of altruism.24

To preserve self-determination to the very end

The WTHD was also seen as a way of preserving self-determination, autonomy or control through to the very end of life. For some patients, the possibility of putting an end to their life, and of exerting some control, became more important as they began to lose more of their capacities.

I will do things my way and to hell with everything and everybody else. Nobody is going to talk me in or out of a darn thing…. What will be, will be; but will be, will be done my way. I will always be in control.23

I am in control of this body […] I will do whatever I want to with it.23

I would like to bring about my own death.11

Will to live, but not in this way

The WTHD also emerged, somewhat paradoxically, as an expression of ‘the will to live, but not in this way’. For some people, not being able to do the things that brought meaning and value to their life was a reason to wish for its end. Many patients mentioned activities that made life worth living (eg, creative activities, reading, driving or enjoying time spent with family and friends), and they felt convinced that when they could no longer do any of those things, their life would be meaningless and they would not want to live anymore.23 Some participants referred explicitly to the paradox of a will to live but not in this way, acknowledging, for example, that they experienced a wish to die at the same time as undergoing active anticancer treatment.10

Functions of the WTHD

Analysis of the reviewed studies suggested that the WTHD can serve two possible purposes or functions: a means of communicating and a form of control.

WTHD as a means of communicating

Although many participants did not refer to this aspect explicitly, the expression of a WTHD served to communicate feelings, thoughts and wishes. In the context of extreme suffering, it represented a ‘cry for help’. In some studies, patients used the WTHD to voice concerns about death and illness.4 24 One patient spoke about how difficult it was to talk about death with her husband, adding that the verbalisation of her WTHD had opened a way into this topic.4

WTHD as a form of control

For some patients, having a sense of their own personal agency brought some relief from present suffering. In this respect, the WTHD was equated with maintaining some control over their life and of avoiding further suffering. In some cases, this control was expressed through hypothetical plans about how they would end their life if things deteriorated. Coyle and Sculco24 refer to this projection into the future as the ‘if-then’ scenario: if my illness progresses and I can no longer bear to suffer, then I will put an end to my life. In countries where euthanasia or assisted suicide are legal, this notion of ‘having a plan’ implied making contact with organisations, or professionals that supported such practices.1 4 9 23

Lived experience of a timeline towards dying and death

The experience of a WTHD was also associated with the sense that time was running out. The anticipation of imminent death and an awareness of the finality of life brought more suffering and disquiet, and it was in this context that, paradoxically, the idea of hastening one’s death came to be seen as a way of putting an end to suffering. Some participants described how they had had to give up the usual things they did.4 23 Such inactivity left them feeling that all they could do was wait as time itself appeared to slow: ‘waiting and waiting, too often, extended, prolonged, so long, on and on, it should be over, limited, until the last moment, and from one second to another’.21

For some people, their WTHD fluctuated over time. In these cases, the wish to live might become stronger as reasons why the person had wished to die became less prominent (eg, their physical pain lessened). However, the balance could then tip the other way depending on their circumstances, such that, at times, a wish to die and a wish to live might both be present.

Discussion

Five years on from our previous meta-ethnography, the inclusion and analysis of seven additional studies has brought greater understanding of the WTHD. Using an approach that France et al15 refer to as ‘extending and renovating the house’, the inclusion of recent literature has enabled us to reclassify categories from our original synthesis into a new set of themes. The new analysis also yielded an additional theme not present in the earlier review. Statements from participants in the additional studies, as well as theorisation proposed by study authors, were key to this reconceptualisation.

Our findings indicate that the primary, overarching theme for an understanding of the WTHD in patients with advanced disease is suffering. This extends to different dimensions of their personhood and thus may involve physical, social, psychological/emotional and/or spiritual/existential suffering. Many patients referred to the deep impact of this suffering on their sense of self or identity, as well as on their immediate surroundings and their ways of coping with life. These findings are consistent with a recent international expert consensus statement, which defined the WTHD as ‘a reaction to suffering, in the context of a life-threatening condition, from which the patient can see no way out other than to accelerate his or her death’.25

Although suffering emerged as the common theme underlying the experience of the WTHD, one participant in the study by Ohnsorge et al4 stated that she was not suffering but because she knew that she would die soon, she wanted death to come faster (without actually having the WTHD). While this is the only case we identified where a WTHD was expressed outside a context of suffering, we do not rule out the possibility that other similar cases may exist. Just as for some patients, death was seen as release from their illness, the patient referred to above seems to have gained some relief from the knowledge that her illness was progressing and that death was imminent.

The second theme, reasons, captures how a WTHD can represent a response to physical, psychological/emotional and social factors in the context of intense suffering and a perceived loss of self. Although physical pain was for many years considered the primary cause of the WTHD, studies conducted since the late 1990s offer a more complex view.26 Thus, while several authors report a close relationship between the WTHD and, for example, greater functional impairment and dependency,27 28 there is evidence to suggest that psychological and emotional factors play an important role in the emergence of such a wish.3 5 26 In terms of a person’s subjective experience, it is not possible to separate physical symptoms and functional impairment from the impact they have on the person’s relationship to his or her surroundings, and the psychological or existential suffering that results. Indeed, physical pain and loss of functionality are inextricably linked with all other aspects of the self and, as such, they may, for example, lead to feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, making it difficult for the patient with advanced disease to find meaning in life. This multifaceted suffering, which cannot be reduced to its constituent parts, exemplifies what Cicely Saunders29 referred to as ‘total pain’. Some participants felt that were it not for their physical pain, they would not wish to die. However, other statements made by patients indicate that the experience of pain cannot be understood in isolation from its impact on the person’s psychological and emotional state and their relationship with the immediate environment. These apparent contradictions may reflect how researchers have explored or assessed pain in this context, since instruments used in cross-sectional studies are unable to capture the full intensity and experiential impact, with qualitative research offering a more nuanced holistic account of the experience of pain.

In our synthesis, psychological factors are prominent as triggers of the WTHD. Quantitative studies, assessing psychological factors related to the WTHD, could add valuable, complementary information to the findings of the qualitative studies. Depression, for example, has been widely reported as a mediating factor for the WTHD.30 31 In a study by Breitbart et al,30 it was observed that patients who presented the desire to die were four times more likely to be depressed than those who did not. In another study, Akechi et al31 showed that, of a sample of 1721 patients, 220 were diagnosed with major depression and that 51.4% of these had suicidal ideation.

In this synthesis, only three of the 14 included studies2 23 24 directly referred to the need to address depression. However, in the light of our analysis of study data, clear symptoms of depression can be detected: loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities, loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness, self-reproach, fearfulness, pessimism and recurrent thoughts of death.32

Similarly, it is important to explore and evaluate hopelessness, helplessness, purposelessness and so on, recurrent states for those who experience the WTHD, as demonstrated by the majority of the participants in our analysis.

Another factor linked to the emergence of the WTHD is demoralisation syndrome, which can be clinically differentiated from depression and is a powerful mediator of the WTHD in these patients.33 34 Three studies included in this synthesis refer to demoralisation.2 4 9 The fact that participants presented hopelessness, loss of meaning and purpose, sense of helplessness, social isolation and lack of support among other findings35 could be symptomatic of demoralisation syndrome, at least in some of the sample. This finding is especially relevant for clinicians, who could implement measures for its detection and treatment.36

Another aspect that was prominent in our synthesis was that many patients referred to the fear of future physical symptoms or future suffering rather than actual current physical symptoms. Our analysis identified that many patients had already experienced episodes of acute poor symptom control with past experience leading them to be fearful when anticipating the future process. In this way, we can further confirm an overlap between physical or psychological factors. Furthermore, we can see how the symptom picture offers a basis for the psychological response to the situation being encountered: in this case, through fear.

While the authors of the included studies identify diverse reasons for the WTHD, these are, in fact, inter-related. In some cases, it is difficult to differentiate the physical, psychological, emotional, social and existential dimensions of patients’ experience. Thus, for example, although aspects such as meaning in life or loss of the sense of dignity are often described as psychological/emotional/existential issues, in our analysis, they relate to the subtheme of loss of self, in other words, a loss of identity that covers all dimensions of personhood.

The concept of dignity in the context of patients with advanced illnesses is crucial because it resolves the inevitable difficulty in trying to delineate physical from psychological suffering. It allows us to understand that patients perceive suffering and simultaneously attribute meaning to their experience. Dignity has been defined as an intrinsic and absolute quality of human beings, which can be perceived as a sense of identity, in relation to physical, psychological, spiritual and social factors mediated by illness.37 The perception of personal dignity, understood as how a person perceives themselves in the light of suffering, the loss of functionality, changes in physical image and so on, along with the emotional impact of experiencing illness, holds special relevance. In this sense, dignity encompasses very different aspects from loss of the sense of dignity mediated by the loss of functionality (loss of bodily function, cognitive impairment, loss of value of life and loss of quality of life) through to dignity understood as personal identity (loss of self-worth, loss of image, loss of self-esteem, loss of social identity: fear of being vulnerable and shame).37–41

The third theme that emerged from our synthesis was meanings. Identifying the meanings the WTHD may hold (other than simply a desire to die) is crucial for understanding the complex and dynamic nature of this phenomenon. Some studies point out how the WTHD can fluctuate over time,42 43 such that an individual may experience contradictory wishes.7 10 24 Such cases highlight the need for caution when exploring the meanings that a given individual may attribute to the expression of a WTHD. Furthermore, although the meanings identified in this updated review were derived from the statements made by participants, the meaning of a WTHD may also be influenced by the values and moral understanding of patients.10 44 In this respect, it is important to explore the cultural and personal background of a patient who expresses a WTHD so as to be able to properly contextualise what is being expressed.

The fourth theme, functions, considers the WTHD as a means of communicating and as a form of control. All the studies revealed that the WTHD served to express more than just a desire to die. The communicative function of the WTHD was clear in some cases, in strengthening family ties and highlighting how important the care and presence of loved ones was to the patient. In some way, the WTHD is also experienced as a way of reducing the burden on family members and of saving them from experiencing a protracted process before death.4 23 Involving relatives in decision making meant that responsibilities were shared and helped ensure, to some extent, that the patient would not be abandoned to their fate. Occasionally, the expression of a WTHD was used to make relatives, friends or professionals feel that they should do more for the patient or to obtain personal gain. In the majority of cases, however, the expression of a WTHD was a way of communicating the extent of suffering.24

The WTHD as a form of control featured in our previous meta-ethnography. For this update, however, our analysis paid closer attention to the legal context, especially in countries in which EAS has been decriminalised. Of the 14 studies, six4 8–11 23 refer explicitly to physicians or organisations that could provide support to persons interested in EAS. Making contact with right-to-die organisations was seen as the final act of control available to someone with a terminal illness. Some patients who expressed this desire for control ended up dying through the administration of lethal drugs.9 23 In countries where such practices remain illegal, patients alluded to hypothetical plans in which the possibility of suicide was contemplated. Such plans appeared to generate a sense of control and of relief among patients (without the irreversibility associated with EAS). Once again, the primary motive for such control was the wish to put an end to suffering. In sum, the existence of legislation that permits EAS can influence decision making for advanced patients at the end of life.4

The final theme, lived experience of a timeline towards dying and death, contextualises patients’ statements within a temporal framework. The experience of time only appeared explicitly (ie, as a theme identified in the data analysis) in one study.21 However, when patients in other studies spoke of their experience of progressive deterioration, fear, anguish, hopelessness and loss of control and so on, they made implicit reference to their life past, present and future. This temporal aspect of the WTHD, captured not only in qualitative studies,45 highlights the importance of a more detailed exploration of patients’ experience when seeking to address their doubts and concerns.

Strengths and limitations

This updated review and synthesis of the published literature on the WTHD has brought a more detailed understanding of the phenomenon. For the present qualitative analysis, two researchers (AR-P and ABo) joined two authors from the previous meta-ethnography (CM-R and ABa), and this triangulation of researchers46 injected a fresh perspective. Inclusion of studies from countries beyond those from the earlier meta-ethnography (specifically, Germany, The Netherlands, Switzerland and Thailand) increases the transferability of results. So far, we have been unable to identify published studies of the WTHD in Africa, South America and the Middle East. As in our previous review, we achieved data saturation in the present study. Only one new theme (‘lived experience of a timeline towards dying and death’) was identified, a theme already implicit in the earlier meta-ethnography. Other themes that emerged encapsulated previously identified themes, which were here reclassified and reconceptualised.

One limitation of the present study concerns the difficulty of synthesising findings from primary qualitative studies. Not all studies used the same conceptualisation of the WTHD, and the research objectives of some studies only touched indirectly on the phenomenon. Likewise, not having access to the original interviews limits the available data.

The analysis necessary to reach a categorisation entails a somewhat forced dissection. For example, the subthemes physical, psychological/emotional and social factors were treated independently in order to be able to analyse them in more depth. However, in the experience of illness, these factors, like the majority of those analysed, are interlinked and inseparable.

Implications for practice and future research

The WTHD is a complex phenomenon to which various reasons, meanings and functions may be attributed. This highlights the need for professionals to be trained so that they can respond to and understand the impact of a life-threatening illness on the individual.

These findings can also provide a number of indicators for ways to improve the healthcare for patients at end of life as suggested in different studies: by focusing on understanding the source of suffering, by enhancing the experience of dignity39 47–49 or meaning in life50 51 or by promoting therapeutic interventions to address demoralisation.36

Healthcare professionals have an important part to play; they are able to acknowledge the meaning of physical symptoms and physical suffering and the role of tending to family members and social factors (including available strategies to guide clinicians in caring for families of dying patients). Additionally, the finding from our qualitative data offer a detailed insight into the fact that frequent symptoms and features of depression (hopelessness, helplessness, loss of self esteem and related sense of burden to others) have important clinical implications for the importance of identifying, assessing and effectively treating depression in this context.

Furthermore, an understanding of the factors that can trigger a WTHD may help to prevent its emergence. From a quantitative perspective, many studies have linked the emergence of the WTHD with the aforementioned factors. Some of these even analyse predictors of the WTHD.28 33 52 53 For example, Rodin et al54 used a structural equation model to support the view that depression, hopelessness and the desire for hastened death represent final common pathways of distress determined by multiple risk and protective factors. Vehling and Mehnert,53 using a similar methodology, showed that loss of dignity partially explains the positive association between the number of physical problems and demoralisation in cancer patients. Robinson et al33 suggest that depressive symptoms, loss of meaning and purpose, loss of control and low self-worth are relevant psychological mechanisms that probably contribute to the development of a desire to hasten death in palliative care patients. Recently, Guerrero-Torrelles et al55 show a model whereby meaning in life (specifically in the sense of diminished meaning) and, to a lesser extent, depression have a mediator effect on the relationship between physical impairment and the WTHD in patients with advanced cancer. Nevertheless, the large majority of quantitative studies have cross-sectional designs, which limit the possibility of establishing causality, as well as only studying variables that could be quantified. In this sense, qualitative studies offer a more in-depth study of the phenomenon as a whole.

It has recently been suggested28 that proactively asking patients about a potential WTHD could be beneficial. Further studies are required to explore this strategy. Given that social factors contribute to the emergence of a WTHD, future research should explore how the expression of a WTHD is experienced by the person’s relatives and what meanings it may have for them. Systematic guidelines regarding the WTHD are needed to help healthcare professionals respond adequately to the needs of these patients.

Conclusions

The WTHD in patients with advanced disease cannot be understood outside the context of their suffering, a prerequisite for its emergence in this population. However, every expression of a WTHD will have associated reasons (the whys) and functions (for what purpose), and its meaning may vary by cultural background and lived experience to not necessarily be synonymous with a genuine desire to die. In countries where EAS have been decriminalised, the expression of a WTHD may be seen as a way to end suffering. All these aspects underline the need to explore the reasons, meanings and functions that a person attributes to such a wish, as only by doing so will we be able to understand his or her experience and develop appropriate individualised care plans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alan Nance for his contribution to translating and editing the manuscript and Amor Aradilla for her contribution at the beginning of the analysis process.

Footnotes

Contributors: CM-R and ABa designed the study. CM-R collected data. CM-R and ARP conducted data analysis. ARP, CM-R and ABa wrote the manuscript. ABa and ABo made substantial contributions to the identification of relevant literature, the interpretation of findings and were involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically. All authors gave final approval to this manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Junior Faculty programme grant, cofinanced by L’Obra Social ‘La Caixa’, the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI14/00263) and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER). We are also grateful for the support given by Recercaixa 2015 and WeCare Chair: End-of-life care at the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya and ALTIMA.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data supporting this study are provided as supplementary information accompanying this paper. Further information can be obtained from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Lavery JV, Boyle J, Dickens BM, et al. Origins of the desire for euthanasia and assisted suicide in people with HIV-1 or AIDS: a qualitative study. Lancet 2001;358:362–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05555-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kelly B, Burnett P, Pelusi D, et al. Terminally ill cancer patients’ wish to hasten death. Palliat Med 2002;16:339–45. 10.1191/0269216302pm538oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hudson PL, Kristjanson LJ, Ashby M, et al. Desire for hastened death in patients with advanced disease and the evidence base of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2006;20:693–701. 10.1177/0269216306071799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ohnsorge K, Gudat H, Rehmann-Sutter C. What a wish to die can mean: reasons, meanings and functions of wishes to die, reported from 30 qualitative case studies of terminally ill cancer patients in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13 10.1186/1472-684X-13-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Monforte-Royo C, Villavicencio-Chávez C, Tomás-Sábado J, et al. What lies behind the wish to hasten death? A systematic review and meta-ethnography from the perspective of patients. PLoS One 2012;7:e37117 10.1371/journal.pone.0037117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nissim R, Gagliese L, Rodin G. The desire for hastened death in individuals with advanced cancer: a longitudinal qualitative study. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:165–71. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mak YY, Elwyn G. Voices of the terminally ill: uncovering the meaning of desire for euthanasia. Palliat Med 2005;19:343–50. 10.1191/0269216305pm1019oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schroepfer TA. Mind frames towards dying and factors motivating their adoption by terminally ill elders. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2006;61:S129–S139. 10.1093/geronb/61.3.S129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dees MK, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekkers WJ, et al. “Unbearable suffering”: a qualitative study on the perspectives of patients who request assistance in dying. J Med Ethics 2011;37:727–34. 10.1136/jme.2011.045492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ohnsorge K, Keller HR, Widdershoven GA, et al. Ambivalence’at the end of life: how to understand patients’ wishes ethically. Nurs Ethics 2012;19:629–41. 10.1177/0969733011436206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohnsorge K, Gudat H, Rehmann-Sutter C. Intentions in wishes to die: analysis and a typology–a report of 30 qualitative case studies of terminally ill cancer patients in palliative care. Psychooncology 2014;23:1021–6. 10.1002/pon.3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Noblit G, Hare R. Meta-ethnography: Sinthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lang H, France E, Williams B, et al. The psychological experience of living with head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Psychooncology 2013;22:2648–63. 10.1002/pon.3343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. France EF, Ring N, Noyes J, et al. Protocol-developing meta-ethnography reporting guidelines (eMERGe). BMC Med Res Methodol 2015;15:103 10.1186/s12874-015-0068-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. France EF, Wells M, Lang H, et al. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Syst Rev 2016;5 1):1 10.1186/s13643-016-0218-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wong SS, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically relevant qualitative studies in MEDLINE. Stud Health Technol Inform 2004;107:311–4. 10.3233/978-1-60750-949-3-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wilczynski NL, Marks S, Haynes RB. Search strategies for identifying qualitative studies in CINAHL. Qual Health Res 2007;17:705–10. 10.1177/1049732306294515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McKibbon KA, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. Developing optimal search strategies for retrieving qualitative studies in PsycINFO. Eval Health Prof 2006;29:440–54. 10.1177/0163278706293400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. CASP P. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Ten questions to help youmake sense of qualitative research. Oxford, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stiel S, Pestinger M, Moser A, et al. The Use of Grounded Theory in Palliative Care: Methodological Challenges and Strategies. J Palliat Med 2010;13:997–1003. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pestinger M, Stiel S, Elsner F, et al. The desire to hasten death: Using Grounded Theory for a better understanding “When perception of time tends to be a slippery slope.”. Palliat Med 2015;29:711–9. 10.1177/0269216315577748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nilmanat K, Promnoi C, Phungrassami T, et al. Moving Beyond Suffering: the Experiences of Thai Persons With Advanced Cancer. Cancer Nurs 2015;38:224–31. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pearlman RA, Hsu C, Starks H, et al. Motivations for physician-assisted suicide. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:234–9. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40225.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coyle N, Sculco L. Expressed desire for hastened death in seven patients living with advanced cancer: a phenomenologic inquiry. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004;31:699–709. 10.1188/04.ONF.699-709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balaguer A, Monforte-Royo C, Porta-Sales J, et al. An International Consensus Definition of the Wish to Hasten Death and Its Related Factors. PLoS One 2016;11:e0146184–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Monforte-Royo C, Villavicencio-Chávez C, Tomás-Sábado J, et al. The wish to hasten death: a review of clinical studies. Psychooncology 2011;20:795–804. 10.1002/pon.1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rodin G, Zimmermann C, Rydall A, et al. The desire for hastened death in patients with metastatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:661–75. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Villavicencio-Chávez C, Monforte-Royo C, Tomás-Sábado J, et al. Physical and psychological factors and the wish to hasten death in advanced cancer patients. Psychooncology 2014;23:1125–32. 10.1002/pon.3536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saunders C. THE LAS STAGES OF LIFE. Am J Nurs 1965;65:70–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA 2000;284:2907–11. 10.1001/jama.284.22.2907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Akechi T, Okamura H, Yamawaki S, et al. Why do some cancer patients with depression desire an early death and others do not? Psychosomatics 2001;42:141–5. 10.1176/appi.psy.42.2.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Endicott J. Measurement of depression in patients with cancer. Cancer 1984;53(10 Suppl):2243–8. 10.1002/cncr.1984.53.s10.2243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Robinson S, Kissane DW, Brooker J, et al. The Relationship Between Poor Quality of Life and Desire to Hasten Death: A Multiple Mediation Model Examining the Contributions of Depression, Demoralization, Loss of Control, and Low Self-worth. J Pain Syptom Manag 2017;53:243–9. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kissane DW, Wein S, Love A, et al. The demoralization scale: a report of its development and preliminary validation. J Palliat Care 2004;20:269–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kissane DW, Clarke DM, Street AF. Demoralization syndrome--a relevant psychiatric diagnosis for palliative care. J Palliat Care 2001;17:12–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robinson S, Kissane DW, Brooker J, et al. A systematic review of the demoralization syndrome in individuals with progressive disease and cancer: a decade of research. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:595–610. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rodríguez-Prat A, Monforte-Royo C, Porta-Sales J, et al. Patient Perspectives of Dignity, Autonomy and Control at the End of Life: Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography. PLoS One 2016;11:e0151435 10.1371/journal.pone.0151435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Street AF, Kissane DW. Constructions of dignity in end-of-life care. J Palliat Care 2001;17:93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chochinov HM, Hack T, McClement S, et al. Dignity in the terminally ill: a developing empirical model. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:433–43. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00084-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Enes SP. An exploration of dignity in palliative care. Palliat Med 2003;17:263–9. 10.1191/0269216303pm699oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guo Q, Jacelon CS. An integrative review of dignity in end-of-life care. Palliat Med 2014;28:931–40. 10.1177/0269216314528399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chochinov HM, Tataryn D, Clinch JJ, et al. Will to live in the terminally ill. Lancet 1999;354:816–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80011-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Galushko M, Strupp J, Walisko-Waniek J, et al. Validation of the German version of the Schedule of Attitudes Toward Hastened Death (SAHD-D) with patients in palliative care. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:713–23. 10.1017/S1478951514000492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rehmann-Sutter C. End-of-life ethics from the perspectives of patients’ wishes : Rehmann-Sutter C, Gudat H, Ohnsorge K, The Patient’s Wish to Die Research, Ethics, and Palliative Care. 1st ed Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:1185–91. 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative Research: Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ 1995;311:109–12. 10.1136/bmj.311.6997.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Martínez M, Arantzamendi M, Belar A, et al. “Dignity therapy”, a promising intervention in palliative care: A comprehensive systematic literature review. Palliat Med 2017;31 10.1177/0269216316665562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brown H, Johnston B, Ostlund U. Identifying care actions to conserve dignity in end-of-life care. Br J Community Nurs 2011;16:238–45. 10.12968/bjcn.2011.16.5.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Östlund U, Brown H, Johnston B. Dignity conserving care at end-of-life: a narrative review. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:353–67. 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Breitbart W. Spirituality and meaning in supportive care: spirituality- and meaning-centered group psychotherapy interventions in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:272–80. 10.1007/s005200100289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 2010;19:21–8. 10.1002/pon.1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kelly B, Burnett P, Pelusi D, et al. Factors associated with the wish to hasten death: a study of patients with terminal illness. Psychol Med 2003;33:75–81. 10.1017/S0033291702006827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vehling S, Mehnert A. Symptom burden, loss of dignity, and demoralization in patients with cancer: a mediation model. Psychooncology 2014;23:283–90. 10.1002/pon.3417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rodin G, Lo C, Mikulincer M, et al. Pathways to distress: the multiple determinants of depression, hopelessness, and the desire for hastened death in metastatic cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:562–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Guerrero-Torrelles M, Monforte-Royo C, Tomás-Sábado J, et al. Meaning in life as a mediator between physical impairment and the wish to hasten death in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;pii: S0885-3924(17)30349-4 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016659supp001.pdf (503.1KB, pdf)