Abstract

Objectives

The disease burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is rising due to suboptimal glycaemic control leading to vascular complications. Medication adherence (MA) directly influences glycaemic control and clinical consequences. This study aimed to assess the MA of patients with T2DM and identify associated factors.

Design

Analysis of data from a cross-sectional survey and electronic medical records.

Setting

Primary care outpatient clinic in Singapore.

Participants

Adult patients with T2DM.

Main outcome measures

MA to each prescribed oral hypoglycaemic agent (OHA) was measured using the five-question Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS-5). Low MA is defined as a MARS-R score of <25. Demographic data, clinical characteristics and investigation results were collected to identify factors that are associated with low MA.

Results

The study population comprised 382 patients with a slight female predominance (53.4%) and a mean±SD age of 62.0±10.4 years. 57.1% of the patients had low MA to at least one OHA. Univariate analysis showed that patients who were younger, of Chinese ethnicity, married or widowed, self-administering their medications or taking fewer (four or less) daily medications tended to have low MA to OHA. Logistic regression revealed that younger age (OR 0.97; 95% CI 0.95 to0.99), Chinese ethnicity (OR 2.80; 95% CI 1.53 to5.15) and poorer glycaemic control (HbA1c level) (OR 1.27; 95% CI 1.06 to1.51) were associated with low MA to OHA.

Conclusions

Younger patients with T2DM and of Chinese ethnicity were susceptible to low MA to OHA, which was associated with poorer glycaemic control. Polytherapy was not associated with low MA.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes mellitus, medication adherence, oral hypoglycemic agent, polytherapy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used a simple five-item questionnaire to measure medication adherence among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on pharmacotherapy.

Assessment of medication adherence to multiple oral hypoglycaemic agents used to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus using a common scale in a single patient is novel.

The case-encounter sampling method employed in this study may restrict extrapolation of the results to the general population.

Introduction

There has been a huge increase globally in the prevalence and disease burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1 One of the countries reporting a steep rise in prevalence is Singapore, a developed nation with a mature healthcare system serving a population of increasing longevity.2 Growing numbers of the local multi-ethnic Asian population on the island-state are developing T2DM and associated complications over longer life spans. As of June 2016, 74.3% of the resident population in Singapore was of Chinese ethnicity, followed by Malays and Indians at 13.4% and 9.1%, respectively.3 Singapore is thus a suitable microcosm for studying the impact of T2DM on the community as most patients have access to treatment in primary care, with 45% currently treated in local public primary care clinics, where medications for diabetes are dispensed to patients from in-house pharmacies at a subsidised cost.2

While medical treatment is readily available to manage the disease in primary care in Singapore, glycaemic control remains suboptimal in 32% of patients with T2DM.2 The mean HbA1c of patients with T2DM attending a primary care clinic was 7.7% (SD 1.7%) in a recent cohort study.4 To achieve glycaemic control, patients are prescribed multiple oral hypoglycaemic agents (OHA) and add on insulin therapy as the disease progresses. Aside from polytherapy, medication adherence (MA) directly influences glycaemic control and clinical consequences. Factors associated with MA tend to be complex due to interactions between the patient, physician, healthcare team and medication factors.5

MA can be measured in several ways, but using questionnaires and scales is easier to integrate into clinical practice.6–8 Instruments such as the 5-item Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS-5) or the 4- or 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) have been used to assess MA.9–12 These scales rely on subjects to self-report their adherence to a specific medication.

Earlier studies have reported low MA to single OHA with the rate varying from 36% to 42% depending on the OHA.13 14 MA assessment becomes more complicated if a patient is on polytherapy or combination therapy to control dysglycaemia. Little research has been carried out to assess MA among patients on polytherapy for diabetes. A systematic review has just commenced to address the issue but no aggregated instrument has been developed for such assessment.15 Assessment is further complicated if patients are taking concurrent medications for the treatment of comorbidities.

One approach is to determine the MA for each OHA prescribed to the individual patient on polytherapy. We hypothesised that patients with T2DM would differ in their MA to each of their prescribed OHA if they were on polytherapy. For optimal glycaemic control, it is important to understand MA to a specific class of OHA, so that appropriate measures can be introduced to address reasons for low adherence. Capoccia et al reported low MA was associated with poor tolerance to medication, frequency of administration beyond twice daily, and incorrect views on the importance of medication.16 A study in Singapore by Quah et al revealed that poor adherence to medications was more prevalent among younger patients with T2DM.17 Hence, we postulated that demographic and medication-related factors might be associated with MA in treatment for diabetes.

Therefore, the main objective of this study was to determine the MA of patients with T2DM to their specific OHA using the MARS-5 scale. This study also aimed to identify the demographic and medication-related factors influencing patient's MA in association with their glycaemic control.

Methods

Study site

A questionnaire survey was administered to patients with T2DM treated with OHA in primary care. The survey was carried out at a typical public primary care clinic (polyclinic) located in SengKang, an estate in north-eastern Singapore. The polyclinic serves a population of over 316 000 multi-ethnic Asian residents living in both the SengKang and neighbouring Punggol estates, covering an area of approximately 20 square kilometres.18 About 9000 patients with T2DM are being followed up at the polyclinic.

Study population

Inclusion criteria

Targeted patients had known T2DM, as confirmed from their electronic medical records at the study site. They were 35 to 84 years of age, of both genders, of different ethnicities, and were followed up at the study site in at least two visits over a minimum period of 6 months.

Subjects were treated with one or more OHA, and sometimes with additional medications for other comorbidities. The OHA included the sulfonylureas (largely tolbutamide, glipizide and gliclazide), biguanides (metformin), alpha-glucosidase inhibitors (AGI, such as acarbose) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4, such as sitagliptin).

Each subject had a minimum of one glycated haemoglobin (HBA1c) result as an indicator of their glycaemic control in the past 6 months.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who were on dietary control alone, were on any form of insulin therapy, or had intellectual or cognitive impairment as stated in their electronic medical record, were excluded.

Recruitment procedure

Potential subjects were screened by trained research assistants and polyclinic nurses for eligibility for enrolment into this survey. They were recruited on a case-encounter basis between June 2015 and March 2016. The study site was a three-storey polyclinic with consultation rooms on the second and third levels. Patients could move freely between the three levels to access various service points, such as diabetic eye and feet screening and laboratory services. While patients were waiting for these services, they were approached by the research assistants and study team members and provided with information on the study protocol using an approved patient information sheet. Their written consent was obtained after their queries were clarified. The patients next filled in the questionnaire, assisted by the research assistants. They were shown pictograms of their OHA as a reminder when they used the MARS-5 scale for each OHA.

Sample size calculation

Based on a low MA rate of 36% from a Malaysian study14 which had a similar multi-ethnic Asian population, the sample size was computed using a confidence interval of 5% and study power of 95%. An estimated sample of 342 eligible subjects would be needed for this study, so in order to allow for a withdrawal rate of 10%, the investigative team planned to recruit 380 patients.

Instrument

Existing scales measure adherence to a single specific medication. However, patients with T2DM are often treated with more than one medication to control hyperglycaemia. Low MA may be specific to a single medication or occur with multiple medications. To investigate MA to multiple medications, the scale must be simple, validated, reliable and easy to implement as it has to be repeated for each medication.

The investigators selected the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS-5) in view of its ease of application. The MARS-5 was developed by Horne et al 19 and has been widely used in studies on a variety of chronic illnesses, including T2DM, hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.11 12 20 21 The MARS-5 has demonstrated acceptable internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.77.22 This is the first study conducted in Asia using the MARS-5 to measure MA in patient with T2DM. Approval to use the MARS-5 was obtained from the developer.

The MARS-5 comprises five questions concerning ‘forgetting’, ‘changing of dosages’, ‘stopping’, ‘skipping’ and ‘using medication less than what is prescribed’. Study subjects indicate the frequency (‘always’, ‘often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘rarely’ or ‘never’) for each question, with ascending scores from ‘always’ (1 point) to ‘never’ (5 points). Scores for each of the five questions are aggregated to give the final score which ranges from 5 to 25 points. A total score of less than 25 points is defined as low adherence to the medication. The MARS-5 was administered for each OHA to compare MA across different types of OHA.

In addition to the MARS-5, a questionnaire was also used to obtain data on the subject’s demographic characteristics (age, gender, sex, marital status, educational level, type of housing) and modes of daily OHA administration. The MARS-5 and the questionnaire were self-administered by the subjects or a family member. Clinical information was retrieved from subjects’ electronic medical records, including data on comorbidities, diabetes-related complications, most recent glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level, and other medications for chronic conditions.

Definition of low MA

A subject treated with multiple OHA who attained a MARS-5 score of 24 or less for any OHA was considered to have low MA, even if they had scores of 25 for other OHA.

Data management and statistical analysis

The data management officer in the investigative team organised, audited and anonymised the data before handing the data set to the biostatistician for data analysis. Data were analysed using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics were computed and expressed as the mean±SD for continuous variables with normal distribution and as the median (inter-quartile range: Q1–Q3) for non-parametric variables. Factors potentially associated with low MA (age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, educational level, type of housing, mode of administration of medication, number of diabetic medications, total number of regular daily medications, number of other chronic diseases, association between any diabetic complication and HbA1c level) were analysed with univariate analysis in which the χ2 or Fisher's exact test were used for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test or independent t-test for continuous variables. Factors shown to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis were included in the multiple logistic regression analysis, with the relationships reflected by ORs (95% CIs). A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study population

A total of 382 patients with T2DM participated in this study. The demographic and clinical characteristic of the patients are shown in table 1. The mean±SD age of the patients was 62±10.4 years with a slight female predominance (53.4%). The majority of the patients were married (77.5%), had attained at least a secondary education (60.5%), lived in public housing (94.2%) and managed their medication on their own (94.2%). Overall, 44.8% of patients had at least one T2DM-related microvascular complication. Their median HbA1c was 7.2% (Q1–Q3: 6.6%–7.9%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population

| Total | Adherent (MARS-5 score of 25) |

Low medication adherence (MARS-5 score of <25) |

p Value | |

| Total | 382 (100.0) | 164 (42.9) | 218 (57.1) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 62 (10.4) | 63.6 (10.1) | 60.4 (10.3) | <0.01 |

| Gender | 0.17 | |||

| Female | 204 (53.4) | 81 (39.7) | 123 (60.3) | |

| Male | 178 (46.6) | 83 (46.6) | 95 (53.4) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.02 | |||

| Chinese | 282 (73.8) | 108 (38.3) | 174 (61.7) | |

| Malay | 36 (9.4) | 19 (52.8) | 17 (47.2) | |

| Indian | 59 (15.4) | 34 (57.6) | 25 (42.4) | |

| Others | 5 (1.3) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | |

| Marital status | 0.02 | |||

| Single | 36 (9.4) | 13 (36.1) | 23 (63.9) | |

| Married | 296 (77.5) | 127 (42.9) | 169 (57.1) | |

| Divorced/separated | 16 (4.2) | 3 (18.8) | 13 (81.3) | |

| Widowed | 34 (8.9) | 21 (61.8) | 13 (38.2) | |

| Highest education | 0.38 | |||

| Up to primary level | 151 (39.5) | 69 (45.7) | 82 (54.3) | |

| Secondary and above | 231 (60.5) | 95 (41.1) | 136 (58.9) | |

| Type of housing | 0.99 | |||

| Public housing | 354 (92.7) | 152 (42.9) | 202 (57.1) | |

| Condo or private apartment/landed property | 28 (7.3) | 12 (42.9) | 16 (57.1) | |

| Mode of administration of medication | 0.04 | |||

| Self-medication | 360 (94.2) | 150 (41.7) | 210 (58.3) | |

| Assisted by family member or domestic helper | 22 (5.8) | 14 (63.6) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Number of diabetic medicines, median (IQR) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 0.08 |

| Number of regular daily medications | 0.04 | |||

| Five or more | 243 (63.6) | 114 (46.9) | 129 (53.1) | |

| Up to four | 139 (36.4) | 50 (36) | 89 (64) | |

| Number of other chronic diseases** | 0.19 | |||

| Three or more | 128 (33.5) | 61 (47.7) | 67 (52.3) | |

| One or two | 254 (66.5) | 103 (40.6) | 151 (59.4) | |

| Any diabetic complications* | 0.25 | |||

| Yes | 171 (44.8) | 79 (46.2) | 92 (53.8) | |

| No | 211 (55.2) | 85 (40.3) | 126 (59.7) | |

| HbA1c, median (IQR) | 7.2 (6.6–7.9) | 7 (6.5–7.7) | 7.3 (6.7–8.2) | 0.01 |

*Diabetic complications include nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy.

**Chronic diseases include hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, ischaemic heart disease, stroke, chronic renal failure, obesity, depression, gout, anaemia, asthma and hypothyroidism.

Patients had been prescribed an average of two OHA (Q1–Q3: 1–2), with the majority prescribed five or more medications for the daily treatment of chronic disease (63.3%). Some 66.5% of patients had at least two other chronic diseases.

MA and associated factors

The median MARS-5 score was 24 (IQR 23–25). A MARS-5 score of <25 for at least one OHA was seen in 57.1% of the study population (table 1). Patients who were younger, of Chinese ethnicity, married or widowed, taking their medications on their own and taking fewer (four or less) daily medications tended to be less adherent to their OHA. Those who were older, married or widowed, assisted by a family member or domestic helper in taking their medications, or taking five or more daily medications seemed to be more adherent to their OHA. Patients who were non-adherent to their OHA had poorer glycaemic control, as reflected in their higher median HbA1c levels.

Logistic regression revealed that patients who were younger, of Chinese ethnicity and with poorer glycaemic control (HbA1c) were associated with low MA to OHA (table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression on factors influencing medication adherence (MA) to oral hypoglycaemic agents

| Low MA (OR, 95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.997) | 0.03 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Indian | Reference | – |

| Chinese | 2.80 (1.53 to 5.15) | <0.01 |

| Malay | 1.24 (0.52 to 2.97) | 0.63 |

| Others | 1.05 (0.15 to 7.50) | 0.96 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | Reference | – |

| Married | 0.95 (0.44 to 2.06) | 0.89 |

| Divorced/separated | 3.20 (0.73 to 14.1) | 0.12 |

| Widowed | 0.79 (0.26 to 2.40) | 0.68 |

| Administration of medication | ||

| Self-medication | Reference | - |

| Assisted by a family member or domestic helper | 0.47 (0.19 to 1.22) | 0.12 |

| Total number of daily/regular medications | ||

| Up to four | Reference | – |

| Five or more | 0.76 (0.48 to 1.21) | 0.24 |

| HbA1c | 1.27 (1.06 to 1.51) | 0.01 |

MA to a specific oral hypoglycaemic agent

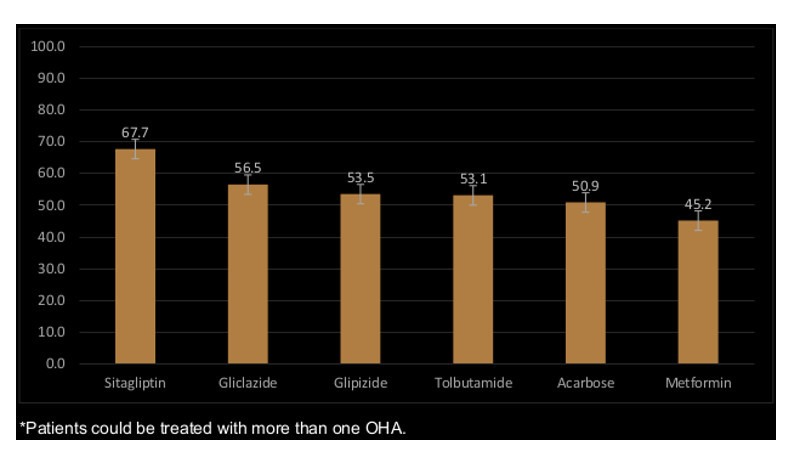

Figure 1 shows the highest MA was among patients taking DPP4 (sitagliptin 67.7%), followed by sulfonylureas (gliclazide 56.5%, glipizide 53.5% and tolbutamide 53.1%), AGI (acarbose 50.1%) and biguanides (45.2%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of medication adherence to specific OHA*.

Discussion

This study found that 57.1% of the study population had low MA to at least one of their OHA, reflected in a MARS-5 score of less than 25. The result is comparable to other studies in developed communities which found low MA ranging from 56.2% to 61.8% using the MARS-5 with similar cut-off points.9 23

Younger patients had lower MA to OHA. As they were more likely to be employees, their working hours could have interfered with their MA. Consequently, their glycaemic control was suboptimal as reflected in their higher HbA1c levels (table 1). This observation corresponded to the results in another local primary care study which also showed that younger patients tended to have poorer glycaemic control.17

Patients who were single, divorced or separated were less adherent to their OHA, compared with those who were married or widowed. DiMatteo in a meta-analysis also reported that MA was higher in patients from cohesive families.24 Family support is vital in the care and MA of patients with long-term illness. Family members or a domestic helper could help to remind the patient of their medication schedule, thus supporting MA (table 1).

Patients with Chinese ethnicity were more than twice as likely to have low MA than those of other minority ethnic groups. Ethnic variation in MA will be explored in a follow-up study using a qualitative research method to examine the context and reasons for this ethnic difference.

The educational level of patients and their socioeconomic status, as reflected by their housing type as a proxy, did not seem to be associated with MA. Jin et al in a meta-analysis alluded to the equivocal effect of educational level on MA.5

The total number of regular medications (OHA and other long-term medications) consumed daily did not seem to affect MA to OHA. Grant et al also found a lack of association between the number of chronic medications and MA.25

Biguanide (metformin) and AGI (acarbose) were associated with a higher proportion of low MA compared with the various sulfonylureas and sitagliptin. Donnan et al found that low MA was associated more with metformin than with sulfonylureas.26 Metformin and AGI are often prescribed in multiple daily doses and are thus susceptible to dose omission. A study by Paes et al reported that once daily regimes led to higher MA than twice or more daily regimes.27 Furthermore, both metformin and acarbose have a higher incidence of adverse gastrointestinal effects, which could affect adherence to these two medications.28 29 In contrast, the once daily regime of DPP4 (such as sitagliptin) showed a more favourable adherence rate compared with other multi-dose OHA. When DPP4 was part of polytherapy, this class of medication showed better MA than sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones.30

This study highlighted the strong association between MA and glycaemic status after adjustment for confounding factors. Patients with low MA to OHA had higher Hba1c levels (median 7.3%, Q1–Q3: 6.7%–8.2%) compared with those who adhered to their OHA (median 7%, Q1–Q3: 6.5%–7.7%). Other studies had similar findings.10 14 31 32

While there was no association between MA and multiple morbidities or T2DM-related complications, a longitudinal study design would be better to determine such a relationship.

The calculated Nagelkerke R2in this study was 12.9%. Other factors which could account for the 87.1% variation in MA include the cost and side effects of medications, complexity of the medication regime, and inadequate medication and diabetes-related knowledge.33–35

Limitations

Measurement of MA can be challenging in clinical practice. There is no single measure which can be used as the gold standard, so a mixed method is considered best to estimate MA.36 However, self-reported screening is practical, easy to implement and inexpensive. A study by McAdam-Marx et al showed that the MARS-5 was comparable to the more complicated method using the modified Medication Possession Ratio (mMPR) by calculating the total days supplied divided by the number of days from the first claim to the last claim plus the days supplied on the last claim.10

Reliance on self-reporting by patients to measure their MA could potentially underestimate the problem. Technology-based tools such as automated counters installed in pill containers have been developed as alternative modes of assessment.37

The lack of a response rate in our study is another limitation. It was not computed to avoid double counting as potential subjects could be approached multiple times by research assistants at different locations at the study site. The case-encounter sampling method employed in this study could restrict extrapolation of the results to the general population. However, this sampling technique is fast and convenient at a study site where subjects can be easily recruited. The medication non-adherence rate found in this study will provide a better estimate for sample size computation for a larger ethnicity-stratified community study using an epidemiological approach in the near future.

Conclusion

Younger patients with T2DM and of Chinese ethnicity were susceptible to low MA. Medication-related factors were not significantly associated with MA. Low MA associated with poorer glycaemic control posed a risk of T2DM-related complications. The use of sustained-release, once-daily OHA and engaging the family to facilitate MA could potentially alleviate the problem, but these measures await evaluation in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the nursing students and their lecturer (Mdm Aaqilah) from Ngee Ann Polytechnic who helped in the recruitment of patients. We are grateful to Professor Robert Horne who kindly permitted use of the MARS-5.

Footnotes

Contributors: CSL, JHMT and NCT were involved in the conception/design of the study. YLEK and US conducted the statistical analysis. CSL and NCT drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (CIRB approval number: 2015/2062) approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Phan TP, Alkema L, Tai ES, et al. Forecasting the burden of type 2 diabetes in Singapore using a demographic epidemiological model of Singapore. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2014;2:e000012 10.1136/bmjdrc-2013-000012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ministry of Health, Singapore National Health Survey, 2010. https:www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/Publications/Reports/2011/national_health_survey2010.html (accessed 30 Sep 2016).

- 3. Department of Statistics Singapore, Population Trends 2016. https:www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/publications-and-papers/population-and-population-structure/population-trends (accessed 5 Jan 2017).

- 4. Tan NC, Barbier S, Lim WY, et al. 5-Year longitudinal study of determinants of glycemic control for multi-ethnic Asian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus managed in primary care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015;110:218–23. 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, et al. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient's perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008;4:269–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. HKh A-Q, Sulaiman SA, Hassali MA, et al. Medication adherence and glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:1028–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Al-Qazaz HK, Hassali MA, Shafie AA, et al. Perception and knowledge of patients with type 2 diabetes in Malaysia about their disease and medication: a qualitative study. Res Social Adm Pharm 2011;7:180–91. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2010.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borgsteede SD, Westerman MJ, Kok IL, et al. Factors related to high and low levels of drug adherence according to patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:779–87. 10.1007/s11096-011-9534-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gialamas A, Yelland LN, Ryan P, et al. Does point-of-care testing lead to the same or better adherence to medication? A randomised controlled trial: the PoCT in General Practice Trial. Med J Aust 2009;191:487–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McAdam-Marx C, Bellows BK, Unni S, et al. Impact of adherence and weight loss on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: cohort analyses of integrated medical record, pharmacy claims, and patient-reported data. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:691–700. 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.7.691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Y, Lee J, Toh MP, et al. Validity and reliability of a self-reported measure of medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Singapore. Diabet Med 2012;29:e338–e344. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aikens JE, Piette JD. Longitudinal association between medication adherence and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2013;30:338–44. 10.1111/dme.12046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sweileh WM, Zyoud SH, Abu Nab'a RJ, et al. Influence of patients' disease knowledge and beliefs about medicines on medication adherence: findings from a cross-sectional survey among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Palestine. BMC Public Health 2014;14:94 10.1186/1471-2458-14-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chua SS, Chan SP. Medication adherence and achievement of glycaemic targets in ambulatory type 2 diabetes patients. J Appl Pharm Sci 2011;01:55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15. McGovern A, Tippu Z, Hinton W, et al. Systematic review of adherence rates by medication class in type 2 diabetes: a study protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010469 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Capoccia K, Odegard PS, Letassy N, et al. Medication adherence with diabetes medication: a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Educ 2016;42:34–71. 10.1177/0145721715619038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quah JH, Liu YP, Luo N, et al. Younger adult type 2 diabetic patients have poorer glycaemic control: a cross-sectional study in a primary care setting in Singapore. BMC Endocr Disord 2013;13:18 10.1186/1472-6823-13-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Department of Statistics Singapore. Population Trends 2016. http://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/publications-and-papers/population-and-population-structure/population-trends/ (accessed 30 Sep 2016).

- 19. Horne R, Weinman J. Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health 2002;17:17–32. 10.1080/08870440290001502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sandy R, Connor U. Variation in medication adherence across patient behavioral segments: a multi-country study in hypertension. Patient Prefer Adherence 2015;9:1539–48. 10.2147/PPA.S91284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tommelein E, Mehuys E, Van Tongelen I, et al. Accuracy of the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS-5) as a quantitative measure of adherence to inhalation medication in patients with COPD. Ann Pharmacother 2014;48:589–95. 10.1177/1060028014522982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Salt E, Hall L, Peden AR, et al. Psychometric properties of three medication adherence scales in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Nurs Meas 2012;20:59–72. 10.1891/1061-3749.20.1.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Farmer A, Kinmonth AL, Sutton S, et al. Measuring beliefs about taking hypoglycaemic medication among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2006;23:265–70. Erratum in: Diabet Med 2006;23(8):931 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 2004;23:207–18. 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grant RW, Devita NG, Singer DE, et al. Polypharmacy and medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1408–12. 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Donnan PT, MacDonald TM, Morris AD, et al. Adherence to prescribed oral hypoglycaemic medication in a population of patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Diabet Med 2002;19:279–84. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00689.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paes AH, Bakker A, Soe-Agnie CJ, et al. Impact of dosage frequency on patient compliance. Diabetes Care 1997;20:1512–7. 10.2337/diacare.20.10.1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dujic T, Zhou K, Donnelly LA, et al. Association of organic cation transporter 1 with intolerance to metformin in type 2 diabetes: a GoDARTS study. Diabetes 2015;64:1786–93. 10.2337/db14-1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Holman RR, Cull CA, Turner RC, et al. A randomized double-blind trial of acarbose in type 2 diabetes shows improved glycemic control over 3 years (U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study 44). Diabetes Care 1999;22:960–4. 10.2337/diacare.22.6.960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Degli Esposti L, Saragoni S, Buda S, et al. Clinical outcomes and health care costs combining metformin with sitagliptin or sulphonylureas or thiazolidinediones in uncontrolled type 2 diabetes patients. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2014;6:463–72. 10.2147/CEOR.S63666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Currie CJ, Peyrot M, Morgan CL, et al. The impact of treatment noncompliance on mortality in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1279–84. 10.2337/dc11-1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aikens JE, Piette JD. Longitudinal association between medication adherence and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2013;30:338–44. 10.1111/dme.12046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kassahun A, Gashe F, Mulisa E, et al. Nonadherence and factors affecting adherence of diabetic patients to anti-diabetic medication in Assela General Hospital, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2016;8:124–9. 10.4103/0975-7406.171696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Labrador Barba E, Rodríguez de Miguel M, Hernández-Mijares A, et al. Medication adherence and persistence in type 2 diabetes mellitus: perspectives of patients, physicians and pharmacists on the Spanish health care system. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017;11:707–18. 10.2147/PPA.S122556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nazir SU, Hassali MA, Saleem F, et al. Disease related knowledge, medication adherence and glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Pakistan. Prim Care Diabetes 2016;10:136–41. 10.1016/j.pcd.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther 1999;21:1074–90. 10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80026-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boeni F, Spinatsch E, Suter K, et al. Effect of drug reminder packaging on medication adherence: a systematic review revealing research gaps. Syst Rev 2014;3:29 10.1186/2046-4053-3-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.