Abstract

Objective

Little is known concerning post-traumatic growth (PTG) after liver transplantation. Against this backdrop the current study analysed the relationship between PTG and time since transplantation on quality of life. Furthermore, it compared PTG between liver transplant recipients and their caregivers.

Design

Cross-sectional case–control study.

Setting

University Hospital in Spain.

Participants

240 adult liver transplant recipients who had undergone only one transplantation, with no severe mental disease, were the participants of the study. Specific additional analyses were conducted on the subset of 216 participants for whom caregiver data were available. Moreover, results were compared with a previously recruited general population sample.

Outcome measures

All participants completed the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory, and recipients also filled in the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey. Relevant sociodemographic and clinical parameters were also assessed.

Results

In the sample of 240 recipients, longer time since transplantation (>9 years) was associated with more pain symptoms (p=0.026). Regardless of duration, recipients showed lower scores on most quality of life dimensions than the general population. However, high PTG was associated with a significantly higher score on the vitality quality of life dimension (p=0.021). In recipients with high PTG, specific quality of life dimensions, such as bodily pain (p=0.307), vitality (p=0.890) and mental health (p=0.353), even equalled scores in the general population, whereas scores on general health surpassed them (p=0.006). Furthermore, liver transplant recipients (n=216) compared with their caregivers showed higher total PTG (p<0.001) and higher scores on the subscales relating to others (p<0.001), new possibilities (p<0.001) and appreciation of life (p<0.001).

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the protective role of PTG in the long-term outcome of liver transplant recipients. Future studies should analyse and develop psychosocial interventions to strengthen PTG in transplant recipients and their caregivers.

Keywords: liver transplantation, posttraumatic growth, quality of life, patients, caregivers

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study on post-traumatic growth in liver transplant recipients and their caregivers.

The study investigates a large sample of 240 liver organ recipients up to 9 years after transplantation.

The study only assesses short-term medical complications in the immediate post-transplant period.

The cross-sectional study design does not allow for the investigation of causal relationships.

The recruitment of patients at a single site may limit external validity of findings.

Introduction

Terminal liver disease is associated with severe physical and psychological decline.1 The best medical option is liver transplantation, which provides longer survival and better quality of life.2–4 However, even after liver transplantation, quality of life often remains below levels found in the general population,5 because acute and chronic graft rejection, recurrence of liver disease or secondary effects of immunosuppressants are very stressful complications for patients and their families,6–8 and may lead to the development of psychological disorders.9–11

Under these circumstances, the concept of post-traumatic growth, which is the idea that stressful life events may create the opportunity to activate one’s resources, leading to a higher level of functioning than before, is highly relevant. This concept, developed by Tedeschi and Calhoun,12 is associated with the positive psychology movement. Basically post-traumatic growth can be regarded as a protective factor12 13 that enables patients to reframe threats into challenges, thereby strengthening their psychological well-being.14 15 Previous studies have found high levels of post-traumatic growth after lung transplantation,6 which were even higher than those observed in patients suffering from chronic heart disease, cancer or HIV. High levels of post-traumatic growth have also been found after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).16 However, lung transplantation and HSCT have markedly lower survival rates than liver transplantation,17 which may have important implications regarding traumatisation as well as post-traumatic growth. To the best of our knowledge, there are only two previous studies dealing with post-traumatic growth in liver transplant recipients.14 15 In a longitudinal study, Scrignaro et al 14 used a sample of 100 liver transplant patients from the outpatient population. Participants filled in the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) and group identification scales at two different times 24 months apart. The results showed that post-traumatic growth positively predicted identification with the family group and the transplantee group over time. The second study by Zięba et al 15 examined 48 liver transplant recipients about 10 weeks after surgery. Recipients told two stories about freely chosen important events in their lives. The measurement of post-traumatic growth 10–12 months later showed that the affective tone of the narratives was associated with the level of post-traumatic growth, and that positive affective tone was related to greater post-traumatic growth. Both studies unveiled potentially important mechanisms by which post-traumatic growth may positively affect well-being. However, the association of post-traumatic growth and quality of life, which is of central importance in the present study, was not dealt with in those papers.

Post-traumatic growth is also highly relevant for close relatives, particularly caregivers of the liver transplant recipient, who is dependent lifelong on medical care and intensive social support. In this situation, the caregiver is confronted with the profound impact of liver transplantation on his or her personal life and its challenging implications.11 18 There is growing evidence regarding the great amount of stress in caregivers before and after liver transplantation, which may even result in symptoms of post-traumatic stress.19 20 The close mutual relationship between transplant recipient and caregiver makes it understandable that caregiver stress may also negatively affect the patient’s quality of life and therapy adherence.

Even though post-traumatic growth is thought to contribute to well-being and quality of life after transplantation, not all previous studies have found a significant positive association between these two variables. For example, Fox et al 6 found in a sample of 64 lung transplant recipients a minimal association between post-traumatic growth and physical functional quality of life. This result illustrates that post-traumatic growth is not related per se to higher quality of life. The relationship between both constructs could be interpreted in the sense that post-traumatic growth increases the likelihood of a flexible adaptation to a new situation, which in the long run is thought to be beneficial to personal well-being.

Against this backdrop, we wanted to clarify this association in liver transplant recipients. Given the importance of this subject in clinical practice, we decided to analyse the relationship between different levels of post-traumatic growth and quality of life and to compare post-traumatic growth of liver transplant recipients and their caregivers. First, we hypothesised that the recipient’s quality of life will be significantly associated with the time elapsed since transplantation as well as the level of post-traumatic growth, in the sense that longer time since transplantation and lower levels of post-traumatic growth are associated with lower quality of life. The negative association between time since transplantation and quality of life is based on the assumption that recipients may increasingly suffer from adverse side effects of immunosuppressants such as pain. Furthermore, in the course of time they may develop serious comorbidities.

Second, we hypothesised that as shown in previous studies, regardless of the time elapsed since transplantation, post-traumatic growth will be significantly higher in recipients than in their caregivers.21–23

Methods

Participants

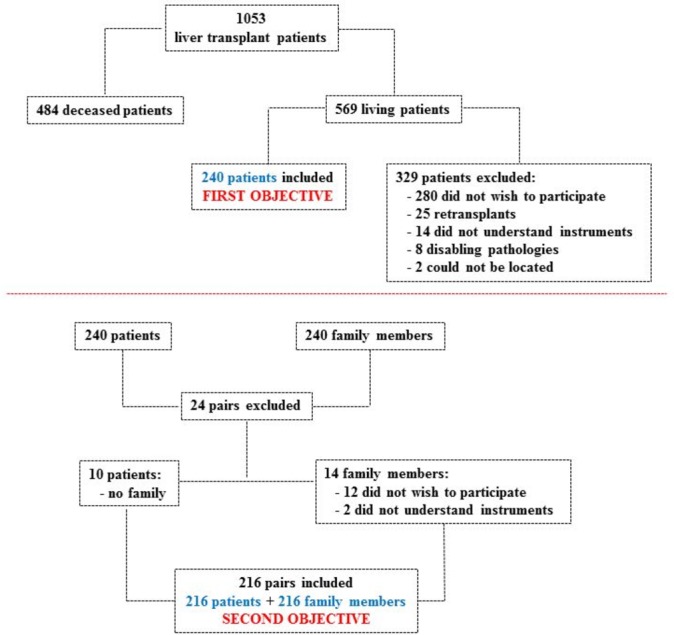

The group of 240 liver transplant recipients selected had undergone transplantation surgery at the Virgen del Rocío University Hospital in Seville from 1990 to 2014. The sample consisted of 185 men and 55 women with a mean age of 60.21 (SD=9.30) years. Of the recipients, 61.7%, 22.5% and 15.8% had a low (did not complete high school), intermediate (high school education) and higher formal education (A level), respectively. Of the participants 79.2% had a stable relationship. The mean number of immediate post-transplant complications, as measured by several medical and laboratory parameters, was 4.47 (SD=2.06). A subsample (figure 1) of 216 recipients and 216 family members (the main caregiver of the respective patient) could be recruited from the total group of 240 recipients. The group of caregivers consisted of 48 men and 168 women with a mean age of 53.19 (SD=12.56) years. Of the caregivers, 88.9% had a stable relationship, and 54.6%, 22.7% and 22.7% had a low, intermediate and higher formal education, respectively. Their family relationships to the recipients were as follows: partner (71.3%), child (19.4%), sibling (4.2%), parent (3.7%) and other (1.4%).

Figure 1.

Participant selection for the study’s two objectives.

In addition, quality of life of the liver transplant patients was compared with a general population sample recruited in a previous study.24 The sample consisted of 4261 individuals (2133 women) with the following age distribution: 18–24 (11.6%), 25–34 (21.1%), 35–44 (20.1%), 45–54 (15.5%), 55–64 (13.7%), 65–74 (10.1%) and ≥75 years (7.8%). Of them, 57.8% were married.24

Measurements

Medical and laboratory parameters

The medical and laboratory parameters refer to the 16 complications described in table 1. Most of the measurements were done in the immunology laboratory and all of them refer to the immediate post-transplant period. The score on the medical parameters was found by scoring participants one point for each complication they had, leading to a value that could range from 0 to 16. Higher values show poorer health.

Table 1.

Medical and laboratory parameters of liver transplant patients in immediate post-transplant period

| Presence | Absence | Data unavailable | |

| Postsurgery haemorrhaging | 24 | 213 | 3 |

| Cytomegalovirus | 211 | 24 | 5 |

| Epstein-Barr virus | 198 | 29 | 13 |

| Bacterial infections | 87 | 151 | 2 |

| Viral infections | 17 | 220 | 3 |

| Fungal infections | 7 | 230 | 3 |

| Acute graft rejection | 47 | 190 | 3 |

| Vascular complications | 7 | 230 | 3 |

| Biliary complications | 27 | 211 | 2 |

| Respiratory complications | 49 | 187 | 4 |

| Refractory ascites | 43 | 195 | 2 |

| Neurological complications | 43 | 194 | 3 |

| Haemodynamic complications | 47 | 189 | 4 |

| Renal complications | 119 | 119 | 2 |

| Haematological complications | 85 | 149 | 6 |

| Reoperations | 29 | 209 | 2 |

Post-traumatic growth

Recipients and caregivers filled in the PTGI.13 This consists of 21 items answered on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘no change’) to 5 (‘very great degree of change’), thereby evaluating the perception of personal benefits in survivors of traumatic events. Test interpretation provides a total score of post-traumatic growth and the following five subdimensions: relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change and appreciation of life. We used the Spanish version provided by Weiss and Berger.25 For patients in this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94 for the sum scale and ranged from 0.73 to 0.88 for the subscales. For caregivers, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95 for the total scale and ranged from 0.77 to 0.90 for the various subscales.

Quality of life

The 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12v.2)26 27 consists of 12 items with either 3-point or 5-point Likert scales. It evaluates the following eight dimensions of health-related quality of life: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health. The score on each dimension varies from 0 (worst state of health) to 100 (best state of health). The reliability of the eight scales varied in our sample from 0.72 to 0.89. In our study, this questionnaire was filled in only by recipients.

Procedure

After receiving an institutional review board approval, we recruited patients and family members from a clinical population of 1053 adult transplant recipients (figure 1). At the beginning, all 569 patients still alive and their main caregivers were informed of the possibility of participation in the study by the Association of Liver Transplant Recipients and the Hepatic-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery and Liver Transplant Unit. The following were the inclusion criteria for both groups: (1) over 18 years of age, (2) informed consent, (3) no difficulties in understanding the evaluation instruments, (4) no severe or disabling psychopathological condition and (5) reception of only one transplant. Thus, 240 recipients could be included in the study, of whom 216 participated along with their caregivers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the sample of 240 transplant recipients was performed using the SPSS V.22 statistics program. Specific additional analyses were conducted on the subset of 216 participants from whom caregiver data were available. A Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare qualitative variables (gender, marital status and education) in the various patient subgroups, and for quantitative variables (age and post-transplant complications) a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test for post-hoc comparisons was calculated. A 2×3 mixed factorial ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc test were performed to evaluate the impact of group factors (liver transplant recipients and caregivers) and time elapsed since transplantation on post-traumatic growth. Time since transplantation was categorised as follows: less ≤3.5 years; medium >3.5 to ≤9 years; more >9 years. A 3×3 factorial ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc test were calculated to analyse the association of time since transplantation (less, medium, more) and post-traumatic growth level (low, medium, high) on quality of life. Cohen’s d (for quantitative variables) and Cohen’s w (for qualitative variables) were computed for effect size.

Results

Quality of life and time since transplantation in transplant recipients (n=240)

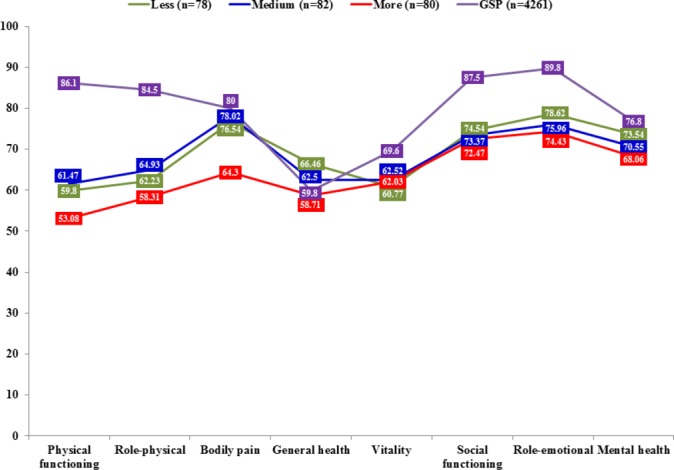

The association between quality of life and time since transplantation as well as post-traumatic growth was studied. In the first part of the analysis, the total sample of 240 patients was divided into three almost equal groups on the basis of time elapsed since transplantation: 78 patients ≤3.5 years (32.5%), 82 patients from >3.5 to ≤9 years (34.2%) and 80 patients >9 years (33.3%). There were no differences among subgroups in gender (p=0.150, w=0.13), marital status (p=0.744, w=0.05), education (p=0.450, w=0.12) or immediate post-transplant complications (p=0.377), although there were significant differences in age (56.46, SD=8.98 vs 59.94, SD=8.39 vs 64.14, SD=9.03; p<0.001). We found no significant interaction effect between time since transplantation and post-traumatic growth on quality of life (table 2, figure 2). The main effect time since transplantation showed a significant effect on the bodily pain dimension (p=0.017) in that after more than 9 years since transplantation recipients showed more pain than after a medium duration of time (>3.5 and ≤9 years) (p=0.026, d=0.41) (table 3). In comparison to the Spanish general population, liver transplant recipients showed lower quality of life on almost all dimensions except for general health regardless of the time since transplantation (table 3, figure 2).

Table 2.

Quality of life: differences between liver transplant recipients by time since transplantation and patient post-traumatic growth levels (3×3 factorial analysis of variance)

| Main effects | Interaction effects | ||

| Time | Post-traumatic growth | ||

|

F

(2, 231)

(p) |

F

(2, 231)

(p) |

F

(4, 231)

(p) |

|

| Physical functioning | 1.199 (0.303) |

0.694 (0.501) |

1.438 (0.222) |

| Role-physical | 0.866 (0.422) |

1.273 (0.282) |

0.848 (0.496) |

| Bodily pain | 4.138 (0.017) |

0.808 (0.447) |

0.760 (0.552) |

| General health | 1.669 (0.191) |

3.706 (0.026) |

0.564 (0.689) |

| Vitality | 0.076 (0.927) |

4.031 (0.019) |

0.254 (0.907) |

| Social functioning | 0.103 (0.902) |

2.440 (0.089) |

0.852 (0.494) |

| Role-emotional | 0.538 (0.585) |

2.370 (0.096) |

1.395 (0.237) |

| Mental health | 1.062 (0.348) |

1.543 (0.216) |

1.129 (0.344) |

Figure 2.

Relationship between time since transplantation and quality of life. Comparison with general Spanish population. Lower mean scores show poorer quality of life. Less (≤3.5 years), medium (>3.5 to ≤9 years), more (>9 years). GSP, general Spanish population.

Table 3.

Quality of life in relation to time since transplantation in transplant recipients (factorial analysis of variance and Bonferroni post-hoc test, Cohen’s d) and compared with a Spanish population sample (unpaired t-test, Cohen’s d)

| Comparisons on time since transplantation* | Physical functioning p (d) |

Role-physical p (d) |

Bodily pain p (d) |

General health p (d) |

Vitality p (d) |

Social functioning p (d) |

Role-emotional p (d) |

Mental health p (d) |

| Less-medium | 1.000 (−0.05 n) |

1.000 (−0.08 n) |

1.000 (−0.04 n) |

1.000 (0.15 n) |

1.000 (−0.06 n) |

1.000 (0.04 n) |

1.000 (0.10 n) |

1.000 (0.13 n) |

| Less-more | 0.737 (0.18 n) |

1.000 (0.12 n) |

0.063 (0.37 s) |

0.207 (0.29 s) |

1.000 (−0.04 n) |

1.000 (0.07 n) |

0.920 (0.16 n) |

0.441 (0.23 s) |

| Medium-more | 0.428 (0.23 s) |

0.573 (0.21 s) |

0.026 (0.41 s) |

1.000 (0.14 n) |

1.000 (0.02 n) |

1.000 (0.03 n) |

1.000 (0.06 n) |

1.000 (0.10 n) |

| Less-GSP | <0.001 (−0.78 M) |

<0.001 (−0.72 M) |

0.414 (−0.10 n) |

0.052 (0.23 s) |

0.013 (−0.29 s) |

<0.001 (−0.46 s) |

<0.001 (−0.45 s) |

0.226 (−0.13 n) |

| Medium-GSP | <0.001 (−0.73 M) |

<0.001 (−0.64 M) |

0.633 (−0.06 n) |

0.420 (0.09 n) |

0.042 (−0.23 s) |

<0.001 (−0.50 M) |

<0.001 (−0.56 M) |

0.029 (−0.25 s) |

| More-GSP | <0.001 (−0.97 L) |

<0.001 (−0.85 L) |

<0.001 (−0.44 s) |

0.748 (−0.04 n) |

0.031 (−0.25 s) |

<0.001 (−0.52 M) |

<0.001 (−0.61 M) |

0.003 (−0.35 s) |

*Less (≤3.5 years), medium (>3.5 to ≤9 years), more (>9 years)

GSP, general Spanish population; L, large effect size; M, medium effect size; n, null effect size; s, small effect size.

Quality of life and post-traumatic growth in transplant recipients (n=240)

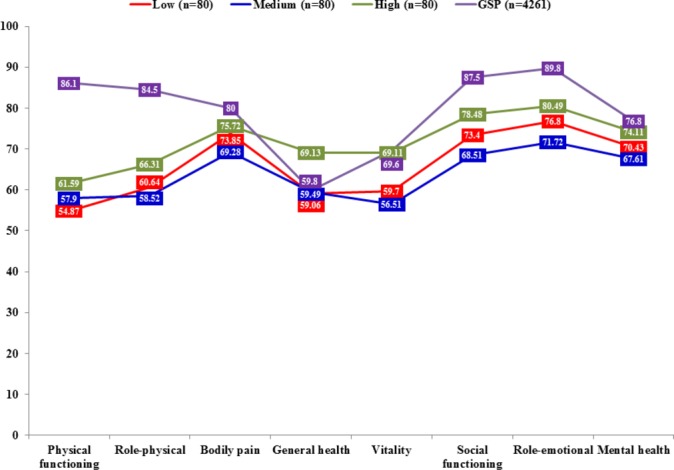

In the second part of the analysis, the sample of 240 patients was divided into three equally sized subgroups on the basis of total post-traumatic growth score: 80 patients with a low level of post-traumatic growth (33.3%; 0–59 points), 80 patients with a medium level (33.3%; 60–77 points) and 80 patients with a high level (33.3%; 78–105 points). There were no significant differences between subgroups concerning age (p=0.506), gender (p=0.639, w=0.06), marital status (p=0.720, w=0.05), education (p=0.187, w=0.16) or post-transplant complications (p=0.443).

There was no significant correlation between post-traumatic growth and time since transplantation (r=0.119; p=0.065). Neither did we find any significant interaction effect between time since transplantation and post-traumatic growth on quality of life (table 2, figure 3). Furthermore, recipients’ post-traumatic growth was significantly related to the vitality dimension, with high compared with medium post-traumatic growth being associated with significantly more vitality (p=0.021, d=−0.43), as well as a statistical trend towards higher scores on general health (p=0.067, d=−0.36), social functioning (p=0.085, d=−0.35) and role-emotional (p=0.093, d=−0.34) with small effect sizes (table 4). Compared with the general Spanish population, liver transplant recipients with lower levels of post-traumatic growth showed a generally lower quality of life. However, a high level of post-traumatic growth was associated with smaller differences, rendering the differences in the vitality (p=0.890, d=−0.02), mental health (p=0.353, d=−0.11) and bodily pain (p=0.307, d=−0.12) dimensions non-significant, even though the latter’s dimension pattern differed, as it also showed a non-significant difference in the subgroup with low post-traumatic growth (p=0.142, d=−0.17). On the general health dimension, there were no significant differences between the general population and the recipients’ subgroups with low (p=0.827, d=−0.03) or medium (p=0.926, d=−0.01) post-traumatic growth. However, the subgroup with high levels of post-traumatic growth showed significantly higher scores on general health compared with the population sample (p=0.006, d=0.33) (table 4, figure 3).

Figure 3.

Relationship between post-traumatic growth level and quality of life. Comparison with general Spanish population. Lower mean scores show poorer quality of life. GSP, general Spanish population.

Table 4.

Quality of life in relation to post-traumatic growth (factorial analysis of variance and Bonferroni post-hoc test, Cohen’s d) and compared with a Spanish population sample (unpaired t-test, Cohen’s d)

| Comparisons on post-traumatic growth level | Physical functioning p (d) |

Role-physical p (d) |

Bodily pain p (d) |

General health p (d) |

Vitality p (d) |

Social functioning p (d) |

Role-emotional p (d) |

Mental health p (d) |

| Low-medium | 1.000 (−0.08 n) |

1.000 (0.06 n) |

1.000 (0.14 n) |

1.000 (−0.02 n) |

1.000 (0.11 n) |

0.853 (0.17 n) |

0.642 (0.20 s) |

1.000 (0.12 n) |

| Low-high | 0.723 (−0.19 n) |

0.792 (−0.18 n) |

1.000 (−0.06 n) |

0.052 (−0.38 s) |

0.130 (−0.32 s) |

0.788 (−0.18 n) |

1.000 (−0.14 n) |

0.971 (−0.16 n) |

| Medium-high | 1.000 (−0.10 n) |

0.374 (−0.24 s) |

0.650 (−0.20 s) |

0.067 (−0.36 s) |

0.021 (−0.43 s) |

0.085 (−0.35 s) |

0.093 (−0.34 s) |

0.244 (−0.28 s) |

| Low-GSP | <0.001 (−0.92 L) |

<0.001 (−0.77 M) |

0.142 (−0.17 n) |

0.827 (−0.03 n) |

0.005 (−0.33 s) |

<0.001 (−0.49 s) |

<0.001 (−0.52 M) |

0.028 (−0.26 s) |

| Medium-GSP | <0.001 (−0.83 L) |

<0.001 (−0.84 L) |

0.011 (−0.30 s) |

0.926 (−0.01 n) |

<0.001 (−0.43 s) |

<0.001 (−0.67 M) |

<0.001 (−0.72 M) |

0.001 (−0.37 s) |

| High-GSP | <0.001 (−0.73 M) |

<0.001 (−0.59 M) |

0.307 (−0.12 n) |

0.006 (0.33 s) |

0.890 (−0.02 n) |

0.004 (−0.32 s) |

<0.001 (−0.37 s) |

0.353 (−0.11 n) |

GSP, general Spanish population; L, large effect size; M, medium effect size; n, null effect size; s, small effect size.

Post-traumatic growth related to time since transplantation in transplant recipients (n=216) compared with their caregivers (n=216)

The sample of 216 liver transplant recipients who could be examined with their caregivers was divided on the basis of time elapsed since transplantation in three subgroups of equal size: 73 patients ≤3.5 years (33.8%), 71 patients from >3.5 to ≤9 years (32.9%) and 72 patients with >9 years (33.3%). There were no significant differences in gender (p=0.128, w=0.14), marital status (p=0.753, w=0.05), education (p=0.683, w=0.10) or medical complications in the immediate post-transplant period (p=0.164) among these subgroups; however, there were significant differences with regard to age (56.37, SD=9.18 vs 60.44, SD=7.65 vs 64.35, SD=9.37; p<0.001).

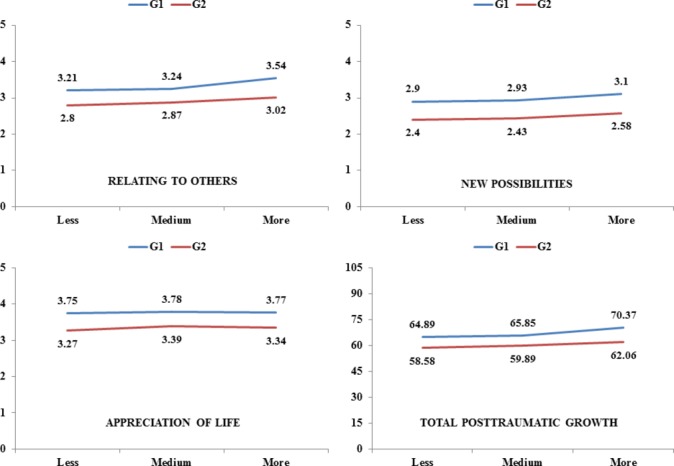

There was no significant effect of between-group interaction and time since transplantation on post-traumatic growth (F=0.196, p=0.822; table 5, figure 4). The main effect time elapsed since transplantation was not associated with post-traumatic growth. However, patients showed significantly higher scores than their caregivers on total post-traumatic growth (p<0.001), as well as on the subdimensions relating to others (p<0.001), new possibilities (p<0.001) and appreciation of life (p<0.001).

Table 5.

Post-traumatic growth: differences between liver transplant recipients (G1) and their caregivers (G2) by time since transplantation (2×3 mixed factorial analysis of variance and Bonferroni post-hoc test)

| Main effects | Interaction effects | Comparisons G1–G2, p (Cohen’s d) |

Comparisons time since transplantation, p (Cohen’s d) |

|||||||||

| Group | Time | Time since transplantation | G1 (n=216) |

G2 (n=216) |

||||||||

|

F

(1, 213)

(p) |

F

(2, 213)

(p) |

F

(2, 213)

(p) |

Less a | Medium b | More c | a-b | a-c | b-c | a-b | a-c | b-c | |

| Relating to others | 23.081 (<0.001) |

1.464 (0.234) |

0.236 (0.790) |

0.008 (0.32) s |

0.020 (0.30) s |

0.001 (0.46) s |

1.000 (−0.02) n |

0.270 (−0.29) s |

0.369 (−0.27) s |

1.000 (−0.05) n |

0.908 (−0.17) n |

1.000 (−0.12) n |

| New possibilities | 33.157 (<0.001) |

0.640 (0.528) |

0.003 (0.997) |

0.001 (0.36) s |

0.001 (0.42) s |

0.001 (0.45) s |

1.000 (−0.03) n |

0.987 (−0.16) n |

1.000 (−0.14) n |

1.000 (−0.02) n |

1.000 (−0.14) n |

1.000 (−0.12) n |

| Personal strength | 0.001 (0.976) |

0.424 (0.655) |

0.744 (0.476) |

0.425 (−0.10) n |

0.868 (−0.02) n |

0.365 (0.13) n |

1.000 (−0.10) n |

0.438 (−0.24) s |

1.000 (−0.14) n |

1.000 (−0.02) n |

1.000 (−0.01) n |

1.000 (0.01) n |

| Spiritual change | 0.001 (0.975) |

2.192 (0.114) |

0.349 (0.706) |

0.898 (0.02) n |

0.537 (−0.08) n |

0.584 (0.07) n |

1.000 (0.04) n |

0.227 (−0.29) s |

0.143 (−0.37) s |

1.000 (−0.06) n |

0.529 (−0.22) s |

0.960 (−0.17) n |

| Appreciation of life | 18.490 (<0.001) |

0.109 (0.897) |

0.067 (0.935) |

0.006 (0.37) s |

0.028 (0.33) s |

0.014 (0.35) s |

1.000 (−0.02) n |

1.000 (−0.02) n |

1.000 (0.00) n |

1.000 (−0.09) n |

1.000 (−0.06) n |

1.000 (0.03) n |

| Total post-traumatic growth | 17.109 (<0.001) |

0.983 (0.376) |

0.196 (0.822) |

0.028 (0.25) s |

0.041 (0.26) s |

0.004 (0.38) s |

1.000 (−0.04) n |

0.417 (−0.24) s |

0.674 (−0.21) s |

1.000 (−0.05) n |

1.000 (−0.14) n |

1.000 (−0.09) n |

a, less; b, medium; c, more; n, null effect size; s, small effect size.

Figure 4.

Post-traumatic growth: mean scores on variables with statistically significant differences between the two groups. Higher scores show more growth. G1, liver transplant recipients (n=216); G2, caregivers (n=216).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first on the relationship between post-traumatic growth and quality of life in liver transplant recipients. In this context we were interested in the patient and in the family support system as represented by the caregiver. We found that, regardless of time elapsed since transplantation, recipients showed more post-traumatic growth than their caregivers. This result confirms our hypothesis and is in keeping with findings in HSCT recipients21 and other patients with cancer.22 23 It might be argued that the patients themselves have been directly exposed to traumatic events such as liver disease, transplant surgery and the side effects of immunosuppressants, which increases the activation of intrapersonal resources, thereby leading to higher levels of post-traumatic growth. Furthermore, liver transplantation symbolises the beginning of a new life for the patient, often after a long period of physical suffering and fear of death. This may be associated with a sense of gratitude towards the deceased donor and the medical team, and a feeling of personal responsibility for justifying all their efforts, which may in turn mobilise a large amount of energy.6 28

The specific aspects of post-traumatic growth, as captured mainly by relating to others, new possibilities and appreciation of life subscales proved to be relevant, as also found in previous studies.16 28 29 Post-traumatic growth did not alter significantly over the course of time, a phenomenon also observed in patients with breast cancer30 and colorectal cancer.31 This may be partially explained by the psychological construct of post-traumatic growth itself, which is described by Tedeschi and Calhoun as:

‘The phenomenon is complex, and cannot easily be reduced to simply a coping mechanism, a cognitive distortion, psychological adjustment or well-being, or a host of apparently similar constructs. The outcomes of posttraumatic growth might be best considered as iterative, and it will take longitudinal work to trace the varied trajectories of the posttraumatic growth process. This process is likely to involve a powerful combination of demand for emotional relief and cognitive clarity, that is achieved through construction of higher order schemas that allow for appreciation of paradox’ (p15).12

Thus the process of post-traumatic growth is thought to be iterative, thereby gradually constructing higher order schemas, which involve rather small slow alterations, relatively stable over time. This is also reflected in the construction of the PTGI, which asks participants to indicate for each statement the degree to which this change occurred during their life as a result of the crisis/disaster. This concrete formulation of a change in life in response to a specific disaster would suggest a stable cognitive-behavioural pattern rather than a state sensitive to fluctuation.

Our hypotheses with respect to quality of life were partially confirmed, since neither time nor post-traumatic growth was significantly associated with all the dimensions of quality of life. Moreover, on most quality of life dimensions, recipients showed significantly lower scores than the general population. In accordance with the above-mentioned definition, one might argue that post-traumatic growth does not immediately lead to higher quality of life, as it mirrors the inner struggle to form a convincing narrative from existential paradoxes associated with life-threatening disease. We found that only the SF-12 bodily pain dimension was significantly related to time since transplantation. This finding may be explained by the increase in immunosuppressant side effects, such as arthralgia and musculoskeletal pain, over time.32 33 In addition our findings displayed particularly low levels of quality of life compared with the general population5 after a post-transplantation time span of over 9 years. In the long run, the combination of the side effects of medication and the restrictions of medical treatment, such as diet and ongoing medical supervision, may negatively affect recipients’ quality of life.

A high level of post-traumatic growth in recipients compared with a medium level was associated with significantly higher scores on vitality, and a statistical trend towards higher scores on general health, social functioning and role emotional. Recipients with high post-traumatic growth vitality scores even equalled scores in the general population. In general, a high level of post-traumatic growth was associated with smaller differences between quality of life scores in recipients and the general population, rendering the differences on bodily pain, vitality and mental health non-significant and revealing even higher scores on general health. These findings highlight the potentially protective role of post-traumatic growth in liver transplant patients and are in keeping with other studies that showed a positive association between post-traumatic growth and quality of life, even though to date the clinical relevance of these findings is not clear.16 30 34 In line with the protective role of post-traumatic growth, personality traits such as extraversion, optimism and openness to experience have been positively associated with this psychological construct.35

From a clinical perspective, the PTGI could be used after liver transplantation to identify those patients who are in special need of psychological support. Mindfulness-based stress reduction36 and positive psychotherapy37 have demonstrated their efficacy in augmenting post-traumatic growth in patients.

Our study had several limitations. First, we did not analyse the relevance of further clinical variables, such as the aetiology of the liver disease,8 or personality variables, such as specific coping strategies, on post-traumatic growth.38 Second, we did not assess long-term transplant-related health parameters, such as infections, rehospitalisation or other complications. Third, recruitment of patients took place at a single site, which may limit external validity of findings. Finally, the study design was not longitudinal, so it was not possible to explore individuals’ change in post-traumatic growth and quality of life over time, which would allow for the investigation of causal relationships.

Nevertheless, the large sample size and the analysis of recipients and caregivers can be seen as a major strength of this study.

Conclusions

To summarise, our study demonstrated that regardless of the time elapsed since liver transplantation, recipients showed more post-traumatic growth than their caregivers. A high level of post-traumatic growth was associated with high levels of specific aspects of quality of life such as vitality, whereas a longer time span since transplantation was related to more pain. Compared with the general population, recipients generally showed lower quality of life, except in patients with high levels of post-traumatic growth, in whom specific dimensions of quality of life, such as bodily pain, vitality, mental health and general health, equalled or even surpassed scores in the general population. Facilitation of post-traumatic growth after liver transplantation may be crucial to ensure long-term quality of life in recipients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants (liver transplant patients and their family members).

Footnotes

Contributors: MÁPSG and AMR: Study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting of manuscript, manuscript revisions, and drafting figures. MBM and MLAN: Study concept and design, and critical revision of article. JPB: Institutional support, data collection and critical revision of article. RC and MÁGB: Data analysis and interpretation, drafting of manuscript and critical revision of article. All authors gave final approval to the version submitted for publication.

Funding: This study was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Project PSI2014-51950-P).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Virgen del Rocío University Hospital of Seville.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data may compromise the privacy of study participants and may not be shared publicly. The public availability of the data is restricted by the Ethics Committee of the Virgen del Rocío University Hospital of Seville (Spain). Data are available upon request to the authors. Contact person: MÁPSG (anperez@us.es).

References

- 1. Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Domínguez-Cabello E, et al. . Quality of life and mental health comparisons among liver transplant recipients and cirrhotic patients with different self-perceptions of health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2013;20:97–106. 10.1007/s10880-012-9309-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martín-Rodríguez A, Pérez-San-Gregorio MA, Domínguez-Cabello E, et al. . Biopsychosocial functioning among cirrhotic patients in various stages of transplant process in comparison to liver transplant recipients. Ann Psicol-Spain 2014;30:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Carroll RE, Turner F, Flatley K, et al. . Functional outcome following liver transplantation - a pilot study. Psychol Health Med 2008;13:239–48. 10.1080/13548500701403363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pantiga C, López L, Pérez M, et al. . Quality of life in cirrhotic patients and liver transplant recipients. Psicothema 2005;17:143–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Masala D, Mannocci A, Unim B, et al. . Quality of life and physical activity in liver transplantation patients: results of a case-control study in Italy. Transplant Proc 2012;44:1346–50. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.01.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fox KR, Posluszny DM, DiMartini AF, et al. . Predictors of post-traumatic psychological growth in the late years after lung transplantation. Clin Transplant 2014;28:384–93. 10.1111/ctr.12301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grinyó JM, Cruzado JM, Bestard O, et al. . Immunosuppression in the ERA of biological agents : López-Larrea C, López-Vázquez A, Suárez-Álvarez B, Stem cell transplantation. New York: Landes Bioscience and Springer Science + Business Media, 2012:60–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pérez-San-Gregorio MA, Martín-Rodríguez A, Domínguez-Cabello E, et al. . Mental health and quality of life in liver transplant and cirrhotic patients with various etiologies. Int J Clin Health Psychol 2012;12:203–18. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cohen M, Katz D, Baruch Y. Stress among the family caregivers of liver transplant recipients. Prog Transplant 2007;17:48–53. 10.1177/152692480701700107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Errichiello L, Picozzi D, de Notaris EB. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders and suicidal ideation in liver transplanted patients: a cross-sectional study. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2014;38:55–62. 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodrigue JR, Dimitri N, Reed A, et al. . Quality of life and psychosocial functioning of spouse/partner caregivers before and after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant 2011;25:239–47. 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2010.01224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Target article:‘Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence’. Psychol Inq 2004;15:1–18. 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress 1996;9:455–71. 10.1002/jts.2490090305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scrignaro M, Sani F, Wakefield JR, et al. . Post-traumatic growth enhances social identification in liver transplant patients: A longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res 2016;88:28–32. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zięba M, Zatorski M, Boczkowska M, et al. . The affective tone of narration and posttraumatic growth in organ transplant recipients. Polish Psychological Bulletin 2015;46:376–83. 10.1515/ppb-2015-0044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tallman B, Shaw K, Schultz J, et al. . Well-being and posttraumatic growth in unrelated donor marrow transplant survivors: a nine-year longitudinal study. Rehabil Psychol 2010;55:204–10. 10.1037/a0019541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kirk AD, Knechtle SJ, Larsen CP, et al. ; Textbook of organ transplantation set. 1st ed Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meltzer LJ, Rodrigue JR. Psychological distress in caregivers of liver and lung transplant candidates. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2001;8:173–80. 10.1023/A:1011317603415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Young GS, Mintzer LL, Seacord D, et al. . Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of transplant recipients: incidence, severity, and related factors. Pediatrics 2003;111:e725–e731. 10.1542/peds.111.6.e725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Young AL, Rowe IA, Absolom K, et al. . The effect of liver transplantation on the quality of life of the recipient’s main caregiver - a systematic review. Liver Int 2017;37:794–801. 10.1111/liv.13333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bishop MM, Beaumont JL, Hahn EA, et al. . Late effects of cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation on spouses or partners compared with survivors and survivor-matched controls. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1403–11. 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Manne S, Ostroff J, Winkel G, et al. . Posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: patient, partner, and couple perspectives. Psychosom Med 2004;66:442–54. 10.1097/00006842-200405000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zwahlen D, Hagenbuch N, Carley MI, et al. . Posttraumatic growth in cancer patients and partners—effects of role, gender and the dyad on couples' posttraumatic growth experience. Psychooncology 2010;19:12–20. 10.1002/pon.1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schmidt S, Vilagut G, Garin O, et al. . [Reference guidelines for the 12-item short-form health survey version 2 based on the catalan general population]. Med Clin 2012;139:613–25. 10.1016/j.medcli.2011.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weiss T, Berger R. Reliability and validity of a Spanish version of the posttraumatic growth inventory. Res Soc Work Pract 2006;16:191–9. 10.1177/1049731505281374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maruish ME. User’s manual for the SF-12v2 health survey. (third edition) QualityMetric Incorporated: Lincoln, RI, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, et al. . How to score Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey (with a supplement documenting Version 1). Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anand-Kumar V, Kung M, Painter L, et al. . Impact of organ transplantation in heart, lung and liver recipients: assessment of positive life changes. Psychol Health 2014;29:687–97. 10.1080/08870446.2014.882922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Widows MR, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M, et al. . Predictors of posttraumatic growth following bone marrow transplantation for cancer. Health Psychol 2005;24:266–73. 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Esparza T, Martínez T, Leibovich de Figueroa N, et al. . Longitudinal study of posttraumatic growth and quality of life in women’s breast cancer survivors. Psicooncología 2015;12:303–14. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Occhipinti S, Chambers SK, Lepore S, et al. . A longitudinal study of post-traumatic growth and psychological distress in colorectal cancer survivor. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139119 10.1371/journal.pone.0139119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Diep JT, Kerr LD, Barton C, et al. . Musculoskeletal manifestations in liver transplantation recipients. J Clin Rheumatol 2008;14:257–60. 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181870212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Movassaghi S, Nasiri Toosi M, Bakhshandeh A, et al. . Frequency of musculoskeletal complications among the patients receiving solid organ transplantation in a tertiary health-care center. Rheumatol Int 2012;32:2363–6. 10.1007/s00296-011-1970-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Geiser F, Imbierowicz K, Conrad R, et al. . [Differences between patients classified as ‘recovered’ or ‘improved’ and ‘unchanged’ or ‘deteriorated’ in a psychotherapy outcome study]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother 2001;47:250–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stanton AL, Bower JE, Low CA. Posttraumatic growth after cancer : Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, The handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2006:138–75. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang JY, Zhou YQ, Feng ZW, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on posttraumatic growth of Chinese breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health Med 2017;22:94–109. 10.1080/13548506.2016.1146405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ochoa C, Casellas-Grau A, Vives J, et al. . Positive psychotherapy for distressed cancer survivors: Posttraumatic growth facilitation reduces posttraumatic stress. Int J Clin Health Psychol 2017;17:28–37. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Borda-Mas M, et al. . Coping strategies in liver transplant recipients and caregivers according to patient posttraumatic growth. Front Psychol 2017;8:18 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.