Abstract

Worsening quality indicators of health care shake public trust. Although safety and quality of care in hospitals can be improved, healthcare quality remains conceptually and operationally vague. Therefore, the aim of this analysis is to clarify the concept of healthcare quality. Walker and Avant’s method of concept analysis, the most commonly used in nursing literature, provided the framework. We searched general and medical dictionaries, public domain websites, and 5 academic literature databases. Search terms included health care and quality, as well as healthcare and quality. Peer-reviewed articles and government publications published in English from 2004 to 2016 were included. Exclusion criteria were related concepts, discussions about the need for quality care, gray literature, and conference proceedings. Similar attributes were grouped into themes during analysis. Forty-two relevant articles were analyzed after excluding duplicates and those that did not meet eligibility. Following thematic analysis, 4 defining attributes were identified: (1) effective, (2) safe, (3) culture of excellence, and (4) desired outcomes. Based on these attributes, the definition of healthcare quality is the assessment and provision of effective and safe care, reflected in a culture of excellence, resulting in the attainment of optimal or desired health. This analysis proposes a conceptualization of healthcare quality that defines its implied foundational components and has potential to improve the provision of quality care. Theoretical and practice implications presented promote a fuller, more consistent understanding of the components that are necessary to improve the provision of healthcare and steady public trust.

Keywords: Concept, concept analysis, healthcare quality, quality, quality of health care, theory

Introduction

Medical errors are now the third leading cause of death in the United States (Makary & Daniel, 2016). The widely acknowledged prevalence of avoidable patient harm and adverse outcomes has led to routine use of the term healthcare quality, with professionals, patients, consumers, and regulatory agencies among the many parties regularly referring to it (Hughes, 2008). Ongoing quality efforts to identify and implement better, more effective patient care practices now exist in virtually every healthcare institution. Evidence suggests that the safety and quality of care in hospitals can be recognizably improved (Pronovost, Thompson, Holzmueller, Lubomski, & Morlock, 2005). Despite these efforts, many quality indicators of healthcare quality have actually worsened, and public trust of hospitals and healthcare professionals continues to erode (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2009). Quality indicators include structure, process, and outcome measures that are reported annually in the National Healthcare Quality Reports, thus providing an overview of the quality of health care in the United States. The most recent National Healthcare Quality Report, published in 2015, reveals a number of measures that showed no change or worsening of quality (AHRQ, 2015a). Similar issues and initiatives also exist in other countries (World Health Organization [WHO], 2003).

An additional challenge noted in these reports is the need to improve data and measures to provide a more complete assessment of priorities (AHRQ, 2014). To do so, however, will require a better understanding of the practices, processes, and initiatives needed to improve patient outcomes within healthcare teams. It will further involve a clear conceptualization of healthcare quality, which has yet to be consistently defined. While attempts to define healthcare quality started in the 1990s, this analysis contributes to new information by encompassing the patient safety dimension.

Aim

The aim of this concept analysis is to analyze healthcare quality in an effort to contribute to a more successful, interactive, team-based implementation of quality improvement efforts in health care. For nurses whose professional roles have expanded beyond direct patient care to include influencing policy, a review of healthcare quality can improve professional and transprofessional communications by increasing understanding, clarifying its definition, and contributing to a shared meaning among stakeholders. Such clarity will support the development of initiatives to improve health care, as well as provide assurances to patients and communities that providing care at the highest standards remains the first concern of nursing.

Background

Healthcare quality spans multiple disciplines. As healthcare quality efforts have evolved in both nursing and the entire healthcare team, variations are noted within and between the disciplinary perspectives. In nursing, quality began with Florence Nightingale. Nightingale, among the first to earn credit for developing a theoretical approach to quality improvement, addressed compromises to nursing and health quality by identifying and working to eliminate factors that hinder reparative processes (Nightingale, 1860). Nearly 140 years later, Nightingale’s ideas continue to influence our healthcare landscape. Hallmark publications, To Err Is Human (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 1999) and Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001), presented quality concerns similarly noted by Nightingale.

In the late 1980s, rising costs of health care resulted in the emergence of managerial and systems views on healthcare quality in both nursing and medicine. Prior to that, physician Avedis Donabedian (1988) proposed a structure, process, and outcomes model, laying the groundwork for an emerging body of consensus measures and tools for assessing the delivery of care. These various but overlapping perspectives reflect the knowledge, views, and values of differing participants in the healthcare experience (Burhans & Alligood, 2010). Donabedian, the IOM reports, and others such as the National Association for Healthcare Quality (n.d.) and the Health Resources and Services Administration (2016) have contributed to the evolution of healthcare quality.

In spite of a concentrated focus over the past two decades, quality issues in health care remain. One issue that may be impeding efforts is a lack of a consistent, uniform definition of quality. For example, Butts and Rich (2013) posited that every American has a definition or personal view of high-quality health care. For some individuals, such a definition revolves around the ability to go to the provider or hospital of their choice; for others, access to specific types of treatment is paramount. Attree (1996) described five perspectives from which quality can be viewed: patient/client, medicine, nursing, purchaser, and provider. For this analysis, we examined the use of the term healthcare quality in the literature to propose a conceptualization of the term that defines its implied, foundational components and provides direction to improve the provision of quality health care. Without an unambiguous definition and clear conceptualization, determining what is and is not quality care is hampered.

Design

We employed the Walker and Avant (2011) concept analysis framework to examine healthcare quality. This eight-step analysis includes the selection of a concept; determining the aim and purpose of the analysis; identifying the uses of the concept; defining the attributes of the concept; constructing a model case example; creating borderline, related, and other case examples; identifying the antecedents and consequences; and defining the empirical referents (Walker & Avant, 2011). Each step is designed to allow transitioning an abstract phenomenon into a meaningful definition with attributes that are practical enough to guide actions that improve healthcare quality and patient safety.

Retrieval and Analysis of Data Sources

We conducted a systematic literature search to identify definitions, outcomes, uses, and attributes of healthcare quality. The search was conducted in five academic databases, including Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed, SCOPUS, Psy Info, and Cochrane Central. Sources through public domain websites and bibliographies of academic literature were also used to examine this concept including governmental and regulatory publications. Webster’s 11th Edition and the Oxford Online English dictionary were assessed for additional definitions and uses of the terms quality and health care.

Because the literature about healthcare quality has exploded in more recent years, the search was limited to publications in English from 2004 to 2016. The terms health care and quality, as well as healthcare and quality, were used to identify literature. Additionally, hallmark sources by Florence Nightingale, Avedis Donabedian, IOM, and AHRQ were included in the synthesis of data.

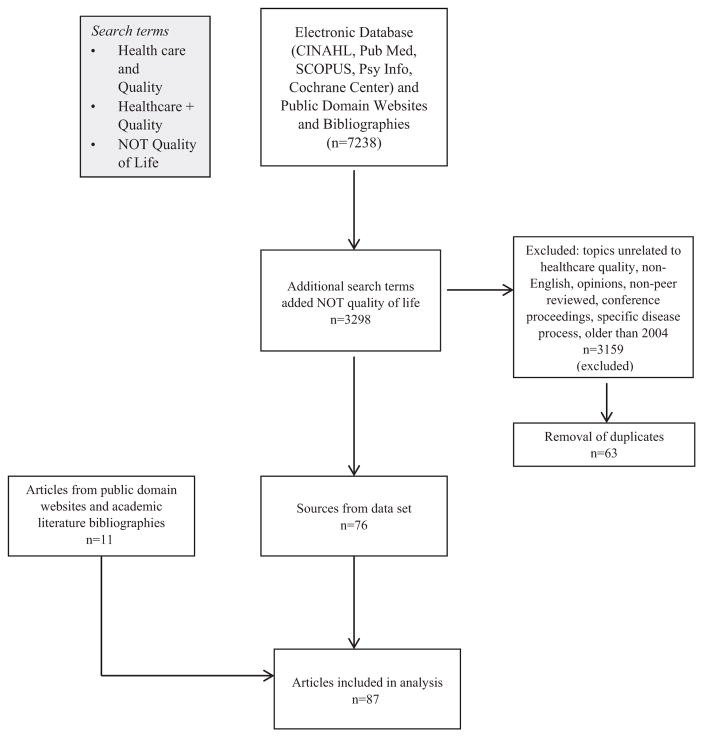

Eligible articles included peer-reviewed journal articles of any study design and government publications. Discussions and opinion papers about quality, gray literature, and conference proceedings were excluded. The first author initially reviewed article titles for eligibility; if deemed potentially eligible, abstracts and full manuscripts were assessed. Each article was evaluated for the definition and/or use of the concept of healthcare quality. If eligibility was unclear, another investigator evaluated the article on the basis of established criteria. The results of the search are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Literature Search

Results

Initially, the keyword search included “healthcare AND quality,” and “health care AND quality,” which generated a combined total of 7,238 articles among the five academic literature databases. We then added “NOT quality of life” and decreased the number to 3,298. As noted earlier, only peer-reviewed articles and government publications were included. Consequently, 3,159 did not meet the inclusion criteria on the basis of preliminary review of the title. Abstracts were then reviewed for inclusion and exclusion criteria. We found 63 duplicates, leaving a total of 76 sources. Eleven additional articles were identified through public domain websites and academic literature bibliographies. In the end, a total of 87 articles were included in the analysis.

Thematic analysis guided the strategy for categorization. The 87 articles were reviewed for common terms in practices. The key components of definitions, concepts, variables, measurements, descriptors, and qualitative design themes were identified in the 87 articles and subsequently listed independently on a worksheet. The individual articles were not grouped into categories. The team reviewed the worksheet for similar terms and descriptors, which were then clustered into emerging themes, leading to the identification of the attributes.

Identified research using the search terms included experimental, systematic reviews, descriptive, exploratory, case studies, and qualitative or mixed-methods designs. The key variables in experimental studies were used to determine the various concepts used to measure quality. For example, in a randomized controlled trial conducted by Dolvich et al. (2016), the primary outcome variable used to measure healthcare quality was a goal attainment scaling score. Additional variables to identify descriptors and measures of healthcare quality were identified in systematic reviews. Engineer et al. (2015) conducted a systematic review of the literature on associations between hospital characteristics and the AHRQ’s Inpatient Quality Indicators, which included mortality rates for selected procedures and medical conditions. In addition to the outcome measures in the systematic review, the hospital characteristics were also reviewed as associated descriptors of healthcare quality. Hospital characteristics included financial resources and staffing ratios (Engineer et al., 2015). Descriptive, exploratory, and case study designs provided meaning and measures of healthcare quality. For example, a descriptive paper by Elf, Frost, Lindahl, and Wijk (2015) described strategies to promote shared decision making in designing healthcare environments to improve quality; they presented processes that involve the mutual exchange of knowledge among stakeholders, collaborative planning, evidence base, and end-user perspectives. A secondary data analysis of a survey on public perceptions and experiences of good-quality healthcare systems reported access, coordination, provider–patient communication, provision of health-related information, and emotional support as the attributes (Doubova et al., 2016).

Of the 76 articles, three used qualitative or mixed-methods designs. In a hermeneutic study by Burhans and Alligood (2010), themes related to the lived meaning of quality nursing care for practicing nurses were advocacy, caring, empathy, intentionality, respect, and responsibility. Themes of communication, relationships and respect, privacy and confidentiality, environment, involvement, preparation, and feeling connected were identified from narrative accounts of young people’s healthcare experiences of quality health care (Edwards et al., 2016). In the third study, staff values and professional standards were two themes that emerged from a grounded theory approach to understand staff perspectives of quality in practice in health care (Farr & Cressey, 2015).

Definitions

Definitions of quality from the commonly available, general use dictionaries included the following: how good or bad something is, a characteristic or feature, high level of value or excellence, and the standard of something as measured against other things of a similar kind (Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 2005). These show a tendency to define the term “quality” in lay language that may be more easily understood. By contrast, in the healthcare articles examined, quality appears to have implications that are considerably broader and more complex. For example, Crosby (1984) described health care quality as a conformance to requirements. Harteloh (2003) suggested that quality implies an “optimal balance between possibilities realized, as well as a framework of norms and values” (p. 9). Furthermore, the American Medical Association (1994, para. 2) defined quality as “the degree to which care services influence the probability of optimal patient outcomes.”

The IOM and the WHO have unique definitions of healthcare quality. The IOM (2013) defines healthcare quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (para. 3). Previously, in 2008, the AHRQ provided a concise and easy-to-understand definition of “doing the right things, for the right patient, at the right time, in the right way to achieve the best possible results” (para. 1). More recently, the AHRQ (2012) adopted the IOM definition of healthcare quality, perhaps in an effort to focus the discussion and defining attributes. Still used, the WHO (2006) provided a definition of healthcare quality as the process of making strategic choices in health systems. Although applicable to each aspect of health care, these definitions vary according to the perspectives and mission of the respective organization or discipline.

Providing a clear, up-to-date theoretical definition of healthcare quality provides a key foundational component of theory-driven research that is necessary for further knowledge development and the provision of quality care. Prior definitions have been similar but lack consistency or specific attributes of the term. A compilation of historical definitions and a review of the recent literature guided this analysis and the identification of the defining attributes. The theoretical definition of healthcare quality that emerged from our analysis is: Healthcare quality is the provision of effective and safe care, reflected in a culture of excellence, resulting in the attainment of optimal or desired outcome.

Defining Attributes

The academic and government publications revealed broad uses of the term “health care quality.” The characteristics most frequently associated with the concept, called the defining attributes, help distinguish the concept from other related concepts (Walker & Avant, 2011). A thematic analysis of the unique characteristics was subsequently collapsed into four categorical themes as the defining attributes: (1) effective, (2) safe, (3) a culture of excellence, and (4) desired outcomes.

Effective, the first defining attribute, refers to features such as proper treatment, including assessment, interventions and response; equitable; consistent; and timely. For example, the Joint Commission (2015) utilizes accountability measures, identified as quality, to determine if care processes have improved health outcomes, whether or not the care process was actually provided, and if the processes are delivered with sufficient effectiveness. A study to determine the meaning of quality care as lived, understood, and articulated by practicing nurses concluded that one feature of effectiveness is making sure that things are not missed or omitted (Burhans & Alligood, 2010). Furthermore, Mosadeghrad (2013) used “consistently delighting the patient by providing efficacious, effective, and efficient care” as a descriptor of quality health care (p. 203). Hospital healthcare quality has been described as hospitals that take charge, work to establish new initiatives, and build protocols and programs (Kahn, 2015). More specifically, turnaround time is one of the most important healthcare performance indicators when describing hospitals’ healthcare quality (Khan et al., 2016). Turnaround time improvement through consistent coordination was successful in improving the effectiveness of healthcare delivery and ultimately quality of health care (Khan et al., 2016). Across the literature reviewed, the provision of quality health care that is accurate and comprehensive and includes continuous assessment of the physiological, psychosocial, sociological, and spiritual status of patients is required. These features were prominent in the literature making effective an essential component of this concept.

The second defining attribute of healthcare quality is safe. Mitchell (2008) indicated that safety is the foundation upon which all other aspects of quality care are built. Various perspectives describing this attribute considered the environmental, physiological, and psychosocial factors of a healthcare event. Safety elements frequently noted in this analysis were infection control practices, accurate medication administration, and adhering to a universal protocol to prevent surgery-related complications. The National Quality Strategy, introduced in 2011 by the AHRQ (2011), described making care safer by reducing harm caused during the delivery of care as a critical aspect of healthcare quality. Additionally, amenable mortality was described by Kamarudeen (2010) as a potential indicator of healthcare quality. Numerous safety outcomes measured as quality indicators led to the emergence of safe as a distinct attribute.

The third attribute of healthcare quality is a culture of excellence. The framework for a culture of excellence that emerged in the literature incorporates collaboration, communication, compassion, competence, advocacy, respect, responsibility, and trustworthiness. Izumi, Baggs, and Knaff (2010) determined that patients’ perspectives of quality health care included scientific, psychosocial, and personal or experiential knowledge; cognitive skills of assessment and decision-making; and effective psychomotor skills. Farr and Cressey (2015) conducted a grounded theory study to assess an understanding of quality of care among primary care staff members. “Staff values and personal and professional standards are essential elements in understanding quality” (Farr & Cressey, 2015 p. 123). Lionis (2015) described compassion as a necessary feature to provide good quality health care and a culture of excellence. Similarly, Carney (2011) found key cultural determinants in quality health care to be excellence in care delivery, ethical values, involvement, professionalism, value for money, and commitment to quality and strategic thinking. Additionally, communication between the healthcare team and with patients must be accurate, consistent, evidence-based, credible and reliable, and understandable.

Desired health outcomes, the final attribute, is characterized by goal achievement, the best possible results, shared decision making, patient centered care, and patient satisfaction. Engaging patients to make decisions about their health is essential in the delivery of quality health care. Identification of a patient’s needs, preferences, and abilities is also essential to promoting the attainment of desired health outcomes. Sidani, Doran, and Mitchell (2004) described these various mechanisms as being responsible for producing favorable and intended outcomes. Dolovich et al. (2016) utilized the attainment of a person’s health goals as an outcome measure of quality. An additional feature of this attribute is subjective well-being. Lee et al. (2013) described the measurement of an individual’s subjective well-being throughout his or her treatment experience as a method to gain a full appraisal of the quality of care that they received. Patient-centered was used by Dupree, Anderson, and Nash (2011) as a necessary effort to deliver quality health care. These four defining attributes lay the foundation of healthcare quality and, as such, are attributes that must all be present for healthcare quality.

Model Case for Healthcare Quality

Several cases were developed on the basis of the defining attributes using the Walker and Avant (2011) method. The model case contains all defining attributes; the related case includes instances of the concept but does not contain all the defining attributes. In the contrary case, the defining attributes are absent.

Model Case

Mr. Smith is being admitted with a diagnosis of pneumonia to the medical surgical unit. He also has lung cancer and several other comorbidities. As he arrives to his assigned room, the admitting registered nurse (RN) is there to greet him and notices that he is in moderate respiratory distress. The RN immediately collaborates with the healthcare team to obtain the appropriate resources that are necessary to improve his acute condition. The competency of the staff is clearly evident as the response to his urgent condition is effective. Safe and timely care is delivered to Mr. Smith during the optimal two-day hospital. The culture of excellence displayed by the entire team ameliorates potential complications. He does not acquire any hospital-associated infections or complications and is free from harm. Mr. Smith’s acute condition improved quickly, but he begins to express his fears of deterioration and suffering due to his terminal illness. The healthcare team listens attentively to his concerns and works with Mr. Smith to determine his desired outcomes. Through shared decision-making between Mr. Smith, his children, and the healthcare team, discharge planning is initiated right away. He is discharged home with adequate resources to maintain optimal psychological and physical well-being, which is deemed as satisfactory to him. This model case includes all critical attributes: effective, safe, a culture of excellence, and desired outcomes.

Borderline Case for Healthcare Quality

Borderline cases contain most of the defining attributes of the concept being examined but not all of them (Walker & Avant, 2011). Mr. Smith is being admitted with a diagnosis of pneumonia to the medical surgical unit. He also has lung cancer and several other comorbidities. As Mr. Smith arrives to his assigned room, the admitting RN is there to greet him and notices that he is in moderate respiratory distress. She collaborates with the healthcare team to obtain the appropriate resources that are necessary to improve his acute condition. His acute condition improves quickly, but he begins to express his fears of deterioration and suffering due to his terminal illness. This concern is expressed on the day of his admission, but an immediate response from the RN is not implemented. Ineffective communication skills were present resulting in the lack of shared decision making between the patient, family, and healthcare team. After a 3-day hospital stay, Mr. Smith is being discharged. As the nurse begins to prepare the discharge, he expresses fears of deterioration and suffering once again. The nurse begins to make arrangements for Mr. Smith and his family to speak with a social worker. Durable medical equipment and in-home nursing care arrangements begin. The hospital stay is extended because the appropriate in-home equipment and clinical care services are not immediately available. After an additional 32 hr in the hospital, Mr. Smith is finally released home. The delivery of health care in this borderline case lacks the timeliness that is necessary to deliver effective care. The additional defining attribute that is not present in this case is the establishment of desired outcomes between the patient and healthcare team. Mr. Smith does not experience any adverse safety outcomes and is discharged home without any hospital-associated infections, yielding the presence of the defining attribute of safety.

Contrary Case for Healthcare Quality

Mrs. Brown is a 72-year-old woman who is transferred from an acute care facility to a skilled nursing facility after having a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Multiple comorbidities require her to receive skilled nursing care before going home. Within 24 hr of arrival to the skilled nursing facility, a complete assessment was not performed by a nurse or physician. Physical therapy services were not obtained. Mrs. Brown’s condition declines rather than improves. On Day 4 of the stay, a physician assesses Mrs. Brown and orders several ancillary tests to determine the cause of the decline. Results of those tests are not communicated with Mrs. Brown or her family. Mrs. Brown’s condition continues to deteriorate. She develops a urinary catheter-associated infection and Stage 2 sacral decubitus ulcer. After a 6-day stay with no improvement, Mrs. Brown’s family requests a transfer out of the skilled nursing facility. All four defining attributes are missing in this contrary case.

Related Concept

An analysis of the concept “health care quality” requires separation of the definition as distinct from alternate or related terms. In this review of the literature and subsequent analysis, it was particularly noted that the terms healthcare quality and patient safety are often used interchangeably. While there is a distinct relationship between healthcare quality and patient safety, a clear distinction exists between the two concepts. Patient safety is often used as a descriptor and characteristic of healthcare quality and is seen in the identified defining attributes for this concept analysis. In the academic literature, patient safety is noted as one of many outcomes associated with healthcare quality.

A thorough concept analysis identifies the unique variables that delineate quality from safety. Based on the results of such an analysis (Kim, Lyder, McNeese-Smith, Leach, & Needleman, 2015), an operational definition of patient safety was described as the outcome of collaborative efforts by healthcare providers in a well-integrated healthcare system aimed at preventing medical errors or avoidable adverse events, thereby protecting patients from harm or injury. The WHO (2015) defines patient safety as the absence of preventable harm to a patient during the process of health care. In 1998, the IOM convened the National Roundtable on Health Care Quality and classified quality problems into three categories: underuse, overuse, and misuse. Misuse was further defined as the preventable complications of treatment and became a common reference point for conceptualizing patient safety as a component of quality (Chassin & Galvin, 1998).

Antecedents and Consequences of Healthcare Quality

Events leading up to or occurring before a concept are the antecedents of the concept (Walker & Avant, 2011). The antecedents for healthcare quality include the need for health care and an actual healthcare event. Healthcare events may be planned or unplanned occurrences. For healthcare quality to exist, the event must occur. Consequences are the incidents or outcomes that occur as a result of the concept. The consequence of healthcare quality is optimal well-being. Optimal well-being goes beyond the curing of illness; it includes physical, spiritual, and emotional wellness in all stages of life from birth to death. However, the lack of healthcare quality can result in adverse health outcomes that may impact quality of life and even result in death.

Empirical Referents

“Empirical referents are classes or categories of actual phenomena that by their existence or presence demonstrate the occurrence of the concept itself” (Walker & Avant, 2011, p. 168). These are the means by which you can measure the defining characteristics or attributes. To measure healthcare quality, several tools specifically aligned with the attributes may be used as proxy measures to determine the abstract concept of healthcare quality. In our review, several tools were available to measure the various attributes of this abstract concept. The Nursing Work Index Practice Environment Survey (NWI-PES), National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI), AHRQ Patient Safety Culture Survey, and Hospital Discharge Abstracts are potential measures. Another tool to measure healthcare quality is Aiken and Patrician’s (2000) NWI-PES tool, a 57-item survey that measures nurse recruitment/retention, job satisfaction, nurse safety, and patient satisfaction providing a measure of the culture of excellence. Widely used and possessing high reliability and validity, this tool provides a measure of desired outcomes through the patient safety subset. The NDNQI, a repository for nursing-sensitive indicators, is the only national nursing database that provides reporting of structure, process, and outcome indicators to evaluate nursing care at the unit level (Montalvo, 2007). The NDNQI measures all four attributes identified in this analysis.a The AHRQ (2015a) patient safety culture survey, a nationally utilized tool, is an extensive evaluation of safety culture within healthcare organizations that also has the potential to measure the defining attributes of healthcare quality. Finally, hospital discharge abstracts provide key elements of measuring healthcare quality, including efficiency, safety, culture, and desired outcomes. Although not all inclusive, the examples of the empirical referents above provide a general overview of potential tools to empirically measure healthcare quality and the identified defining attributes. However, there are empirical measures for the individual characteristics that led to the defining attributes, and may be necessary to measure less abstract concepts that will serve as a proxy to healthcare quality.

Discussion

Conveying an improved understanding of healthcare quality is a vital, preliminary step toward healthcare quality research and initiatives. Without a clear meaning, quality improvement is likely to be fragmented or ineffective. The structure and function of this abstract phenomenon provided in this manuscript are necessary for constructing a theoretical, yet testable, framework. This conceptualization of healthcare quality makes it easier to measure quality indicators and use healthcare quality to investigate its relationship with other concepts within the healthcare environment. Clarity of definition and defining attributes also provides insight for evaluating other existing frameworks. Additionally, each individual attribute may serve as a guide to theory development or the testing of existing theories in future research.

The theoretical definition provided through our analysis supports basic elements for the development of current nursing knowledge and may enhance professional and transprofessional communications, ultimately contributing to the improvement of quality efforts in and among healthcare organizations. A definition incorporating recognizable attributes among the nursing profession delivers the consistency necessary for valuable conversations between nursing science and nursing practice.

Strengths/Limitations

The concept analysis and thematic classification represent the most prevalent characteristics noted in the current academic literature, which is a strength in battling today’s threats to optimal patient outcomes. The specific search strategy of five databases and only searching literature from the past 12 years may pose limitations. Additionally, some relevant data sources may have been omitted, as non-English languages and gray literature were not included.

Conclusion

This concept analysis of healthcare quality informs theory building for health science, as well as the development of quality initiatives. Identifying the critical attributes is essential to clarity, further instrument development, and theory building. Future research using this component of a theoretical framework, combined with an additional concept such as patient outcomes, may yield significant knowledge development in the provision of evidence-based nursing care.

Donabedian (1988) described an earlier framework for the assessment of healthcare quality. The defining attributes of healthcare quality in the present analysis—safe, effective, culture of excellence, and desired outcomes—can clearly be situated in his model of structure, process, and outcome whereby each component is interdependent (Gardner, Gardner, & O’Connell, 2014). By employing the Donabedian framework and careful examination of the concept of healthcare quality, a proposed relational statement can be postulated to determine relationships, ultimately informing quality improvement practices.

In addition to the theoretical implications, the result of this analysis provides practice implications that can be used to guide quality initiatives in several healthcare disciplines. The defining attributes can be used as performance measures in a variety of nursing settings such as administrative, clinical, performance improvement, financial, and policy development. Instrument development to measure healthcare quality based on the four attributes identified represents an avenue of future research. Developing a tool and constructing items to reflect the defining attributes would improve empiric indicators of the concept.

Each theoretical, practice, and research implication has the potential to better our understanding of what actions are needed to improve the provision of health care. As noted by the Director of AHRQ (Clancy, 2009; Hughes, 2008) and in The Future of Nursing (IOM, 2011), nurses are critical to improving quality and providing quality assurance. The possibilities to secure public safety and trust are within our reach.

Acknowledgments

Jennifer C. Robinson is partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 1U54GM115428. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Angela Allen-Duck, PhD student, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS.

Jennifer C. Robinson, Professor of Nursing, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS.

Mary W. Stewart, Professor of Nursing, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The way forward-promoting quality improvement in the states: Diabetes care quality improvement. Rockville, MD: Author; 2008. Retrieved from http://archive.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resource/tools/diabguide/diabguidemod6.html. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National healthcare quality report. Rockville, MD: Author; 2009. Retrieved from http://archive.ahrq/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqr09/Key.html. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The national quality strategy. Rockville, MD: Author; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/ [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality management: Child health care quality toolbox. Rockville, MD: Author; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/profressionals/quality-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National healthcare quality report. Rockville, MD: Author; 2015a. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr14/2015nhqdr.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Surveys on patient safety culture. Rockville, MD: Author; 2015b. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/profesionals/quality-patient-safety/patientsafetyculture/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, Patrician P. Measuring organizational traits of hospitals: The revised Nursing Work Index. Nursing Research. 2000;19(3):146–153. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. Attributes to guide the development of practice parameters. 1994 Retrieved from http://www.acmq.org/policies/policies1and2.pdf.

- Attree M. Towards a conceptual model of quality care. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1996;33(1):13–28. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(95)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burhans L, Alligood M. Quality nursing care in the words of nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;66(8):1689–1697. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts J, Rich K. Nursing ethics: Across the curriculum and into practice [book review] Online Journal of Health Ethics. 2013;2(2):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin M, Galvin R. The urgent need to improve health care quality. Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on health care quality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1000–1005. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy C. AHRQ Director says nurses are important leaders in improving health care quality. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2009/01/ahrq-director-says-nurses-are-important-leaders-in-improving-hea.html.

- Crosby P. Quality is free. Health Affairs (Spring) 1984;7:49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dolovich L, Oliver D, Lamarche L, Agarwal G, Carr T, Chan D, … Price D. A protocol for a pragmatic randomized control trial using the Health Teams Advancing Patient Experience: Strengthening quality platform approach to promote person-focused primary healthcare for older adults. Implementation Science. 2016;11(49):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0407-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. The criteria and standards of quality. Journal of American Medical Association. 1988;260:1743–1748. Retrieved from http://www.nursingworld.org/DocumentVault/Care-Coordination-Panel-Docs/background-docs/Jun-4-Mtg-docs/The-Quality-of-CareHowCanItBeAssessed-Donabedian1988.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Doubova S, Guanais F, Perez-Cuevas R, Canning D, Macinko J, Reich M. Attributes of patient-centered primary care associated with the public perception of good healthcare quality in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and El Salvador. Health Policy and Planning. 2016 Feb;2013:834–843. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupree E, Anderson R, Nash I. Improving quality in healthcare: Start with the patient. Mt Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2011;78(6):813–819. doi: 10.1002/msj.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M, Lawson C, Rahman S, Conley K, Phillips H, Uings R. What does quality healthcare look like to adolescents and young adults? Ask the experts! Clinical Medicine. 2016;16(2):146–151. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-2-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elf M, Forst P, Lindahl G, Wijk H. Shared decision making in designing new healthcare environments—time to begin improving quality. BioMedical Central Health Services Research. 2015;15(114):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0782-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr M, Cressey P. Understanding staff perspectives of quality in practice in healthcare. Biomed Central Health Services Research. 2015;15:123–132. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0788-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner G, Gardner A, O’Connell J. Using the Donabedian framework to examine the quality and safety of nursing service innovation. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014;23(1/2):145–155. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harteloh P. The meaning of quality in health care: A concept analysis. Health Care Analysis. 2003;11(3):259–267. doi: 10.1023/B:HCAN.0000005497.53458.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources & Services Administration. Strategic plan goal 1: Improve access to quality health care and services. 2016 Retrieved March 18, 2016, from http://www.hrsa.gov/about/strategicplan/goal1.html.

- Hughes RG. Tools and strategies for quality improvement and patient safety. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. pp. 1–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. To err is human. 1999 Retrieved from https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. Retrieved from http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. Retrieved from https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2010/The-Future-of-Nursing/Future%20of%20Nursing%202010%20Recommendations.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. IOM definition of quality. 2013 Retrieved from http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.

- Izumi S, Baggs J, Knaff K. Quality nursing care for hospitalized patients with advanced illness: Concept development. Research in Nursing and Health. 2010;33:299–315. doi: 10.1002/nur.20391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M, Khalid P, Al-Said Y, Cupler E, Almorsy L, Khalifa M. Improving reports turnaround time: An essential healthcare quality dimension. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2016;26:205–208. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-664-4-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim L, Lyder C, McNeese-Smith D, Leach L, Needleman J. Defining attributes of patient safety through concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2015;71(11):2490–2503. doi: 10.111/jan.12715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionis C. Why and how is compassion necessary to provide good healthcare? International Journal of Health Policy Management. 2015;15(4):771–772. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makary M, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. British Medical Journal. 2016;36(22):2124–2134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. Defining patient safety and quality care. In: Hughes R, editor. Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. pp. 13–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo I. The national database of nursing quality indicators. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2007;12(3):1–7. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01PPT05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosadeghrad A. Healthcare service quality: Towards a broad definition. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance. 2013;26(3):203–219. doi: 10.1108/09526861311311409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association for Healthcare Quality. About NAHQ. n.d Retrieved March 18, 2016, from http://www.nahq.org/about/whoweare/whoweare.html.

- Nightingale F. Notes on nursing: What it is and what it is not. New York: Appleton; 1860. [Google Scholar]

- Pronovost P, Thompson D, Holzmueller C, Lubomski L, Morlock L. Defining and measuring patient safety. Critical Care Clinics. 2005;19:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidani S, Doran D, Mitchell P. A theory-driven approach to evaluating quality of nursing care. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;36(1):60–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. Top performer on key quality measures. 2015 Retrieved July 27, 2016, from https://www.jointcommission.org/accreditation/top_performers.aspx.

- Walker L, Avant K. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. 5. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. 11. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Quality and accreditation in health care services: A global review. 2003 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hrh/documents/en/quality_accreditation.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Quality of care: A process of making strategic choices. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.who.int.iris/handle/10665/43470.

- World Health Organization. Patient safety. World Health Organization; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/patientsafety/about/en/ [Google Scholar]