Abstract

Wheat amylase/trypsin bi-functional inhibitors (ATIs) are protein stimulators of innate immune response, with a recently established role in promoting both gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal inflammatory syndromes. These proteins have been reported to trigger downstream intestinal inflammation upon activation of TLR4, a member of the Toll-like family of proteins that activates signalling pathways and induces the expression of immune and pro-inflammatory genes. In this study, we demonstrated the ability of ATI to directly interact with TLR4 with nanomolar affinity, and we kinetically and structurally characterized the interaction between these macromolecules by means of a concerted approach based on surface plasmon resonance binding analyses and computational studies. On the strength of these results, we designed an oligopeptide capable of preventing the formation of the complex between ATI and the receptor.

Introduction

In the last decades, the implementation of novel agricultural practices contributed positively to the decrease of costs associated with large-scale production of wheat-based food. Consequently, the higher consumption of breads and pastas caused a predictable increase in hypersensitization to wheat. The most common of these disorders include baker’s asthma1, and immune reactions to wheat ingestion, such as celiac disease (CD), wheat allergy (WA), and non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivity (NCGS or NCWS)2–5.

CD is triggered by gluten peptides that induce the adaptive immune response in predisposed individuals, resulting in the activation of T-cells6,7, whereas IgE antibodies are induced by wheat proteins in WA, eventually stimulating the release of immune mediators8.

On the other hand, NCGS is associated with innate immune activation, which is likely stimulated by wheat proteins9,10. NCGS presents also extra-intestinal symptoms11, such as confusion and headache, chronic fatigue, joint/muscle pain, and the exacerbation of pre-existing neurological, psychiatric, or (auto-)immune diseases4,12,13.

Based on their structural, chemical and physical properties10, wheat proteins are generally categorized as albumins and globulins (15% of total protein content), and gluten (85% of total protein content). Specifically, gluten consists of a complex mixture of monomeric gliadins and polymeric glutenins, whereas albumins and globulins comprise several families of proteins, such as the α-amylase/trypsin inhibitors (ATIs), β-amylases, peroxidases, lipid transfer proteins, and serine proteases inhibitors10. In the quest to identify wheat components effectively responsible for the initiation of innate immune response, ATIs were demonstrated as potent activators of myeloid cells. Specifically, ATIs directly engage TLR4–MD2–CD14 complex and activate both nuclear factor kappa B and interferon responsive factor 3 pathways, resulting in the up-regulation of maturation markers and the release of proinflammatory innate cytokines14. The centrality of TLR4 system was further confirmed, as animal models deficient in TLR4 were protected from the intestinal and systemic immune responses upon oral challenge with ATIs15.

Compared to other protein constituents, ATIs represent a minor, but still significant part of total wheat proteins (2–4%)16, on average, an adult person being exposed up to 1 g of ATIs per day: in fact, ATIs are present and even enriched in commercial wheat-based food17, and can escape proteolytic digestion by pepsin and trypsin, preserving the TLR4-activating ability after intestinal transit upon oral ingestion18.

Structurally, wheat ATIs belong to a group of hydrolase-resistant proteins stabilized by inter-molecular disulfide bonds19, and with high secondary structural homology15. They can be further divided into three sub-groups constituted by monomeric and (non-covalently linked) dimeric and tetrameric forms20. ATIs are found in the endosperm of plant seeds, where they represent part of the natural defence against parasites and insects, as well as regulatory molecules of starch metabolism during seed development and germination21,22. Plants other than wheat, such as rye and barley also contain similar bi-functional inhibitors, but show only minimal or absent TLR4-activating activity15.

Due to the in vivo TLR4 stimulatory activity and resistance to gastrointestinal proteolysis15, this latter being attributable to the potent inhibitory activity toward diverse hydrolases23, ATIs may exert a pathogenic role in inflammatory, metabolic and autoimmune diseases and in NCGS11,24,25.

On the strength of the interplay between ATIs and TLR4, in this study we used the IAsys plus system to explore the kinetics of the interaction between a representative member of wheat ATI family, namely CM3, and human TLR4. In addition, we performed molecular docking studies to predict the structural basis of ATI-TLR4 complex, evaluating the most probable binding sites and interaction forces, and identifying the residues at the binding interface. Interestingly, besides revealing univocally a high-affinity interaction between the two macromolecules, the results of the concerted computational and binding studies led to design an oligopeptide constituting part of the discontinuous ATI binding interface with TLR4, which was able to prevent the interaction between the two macromolecules.

Results

Biosensor binding studies

Carboxylate cuvettes were selected to covalently immobilize TLR4 via primary amines. The very high stability of the resulting biosensing layer combined with the low instrumental short-term noise (less than 1 arcsec) granted an accurate determination of both kinetic and equilibrium parameters of the interaction between human TLR4 and wheat ATI CM3 under different pH and ionic strength conditions. The superimposition of representative association kinetics obtained upon binding of different concentrations of ATI to TLR4 (PBS pH 7.4, supplemented with 140 mM NaCl) is reported in Fig. 1, Panel A. Raw data were routinely accumulated over a 6-min interval. Association and dissociation curves were fitted to both mono- and bi-exponential models: since bi-exponential models did not significantly improve the quality of fits, as judged by standard F-test, 95% confidence, the mono-exponential models (Eqq. 3 and 5, see Method section) were used throughout to analyse the data.

Figure 1.

Binding of ATI to surface-blocked TLR4. Superimposition of sensorgrams obtained at increasing concentrations of the bi-functional inhibitor (Panel A). Extent of binding vs concentration plot (Panel B).

This experimental approach evidenced the high-affinity interaction between soluble ATI and surface-blocked receptor (K D, kin = (6.1 ± 1.7) × 10−8 M, as calculated from the ratio of kinetic parameters derived from Eq. 2). Both fast association (k ass = (4.1 ± 0.6) × 104 M−1 s−1) and slow dissociation (k diss = (2.5 ± 0.6) × 10−3 s−1) phases significantly contributed to the stabilization of the complex.

The binding response at equilibrium (extent of binding) was calculated for each time course, with fully comparable equilibrium dissociation constant value (K D, ext = (3.6 ± 1.5) × 10−8 M, as directly calculated from Eq. 4) with respect to values derived from kinetic analyses (Fig. 1, Panel B).

Binding stoichiometry was determined to be 1:1, as calculated from the molar ratio between surface-blocked TLR4 (59 μM, directly estimated from the biosensor response upon immobilization) and soluble ATI (60 μM, derived from the extent of binding at saturating concentration of the bi-functional inhibitor).

Effect of pH and ionic strength

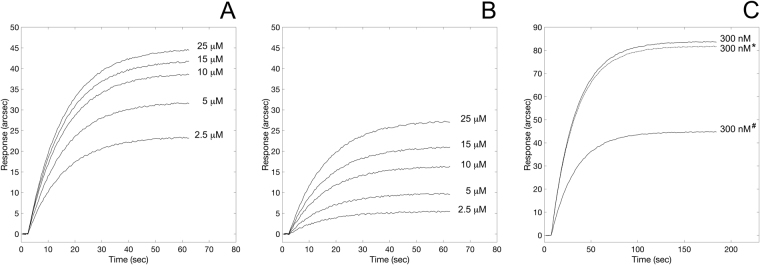

We investigated the influence of pH and ionic strength on the kinetic and equilibrium parameters of the binding between ATI and TLR4 (all parameters are summarized in Table 1). At lower salt concentrations, negatively-charged TLR4 bound with higher affinity to ATI, exclusively due to the higher kinetic stability of the ATI-TLR4 complex (lower value of kinetic dissociation constant). Both complex affinity and kinetic stability progressively decreased with increasing ionic strength, with a final 25-fold loss in complex stability (as also evident from the progressive increase in the slope of the dissociation phases with NaCl concentration, Fig. 2). For this reason, we used PBS supplemented with 200 mM NaCl instead of using HCl 10 mM for the regeneration step (this procedure being likely to cause denaturation of the macromolecule blocked on the cuvette surface). Conversely, kinetics of association were not affected by salt concentration, the changes in k ass values being negligible within experimental errors.

Table 1.

Effect of ionic strength on kinetic and equilibrium parameters of the interaction between wheat ATI and TLR4.

| Ionic strength conditions | kass (M−1s−1) | kdiss (s−1) | KD (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 mM PBS (no NaCl) | 43000 ± 2000 | 0.0001 ± 0.00005 | (2.3 ± 1.2) × 10−9 |

| 20 mM PBS (25 mM NaCl) | 39000 ± 4000 | 0.0004 ± 0.0002 | (1.0 ± 0.5) × 10−8 |

| 20 mM PBS (50 mM NaCl) | 40000 ± 2500 | 0.0007 ± 0.0001 | (1.8 ± 0.3) × 10−8 |

| 20 mM PBS (140 mM NaCl) | 41000 ± 6000 | 0.0025 ± 0.0006 | (6.1 ± 1.7) × 10−8 |

Figure 2.

Effect of ionic strength lowering on the interaction between ATI and surface-blocked TLR4. Superimposition of sensorgrams obtained at increasing concentrations of the bi-functional inhibitor, each at different ionic strength conditions.

Neither kinetic nor equilibrium parameters showed significant dependence from pH in the range 6–8 (data not shown).

Electrostatic potential maps

ATI-TLR4 complex was mainly stabilized by electrostatic interactions. In fact, TLR4 revealed a large, global negative charge (for pH values higher than 5), whereas ATI, presenting both positively and negatively charged surfaces, was supposed to act as a protein dipole (See Supplementary Information). These results were in good agreement with the effects induced by changes in the dielectric constant of the buffer solution on complex stability (high ionic strength conditions strongly destabilized ATI-TLR4 complex).

Docking analysis of ATI to TLR4

Docking studies between the fold-recognition model of wheat ATI CM3 (see Experimental Section for details) and the X-ray crystal structure of the human TLR4-MD2 complex disclosed new insights regarding both the nature of the interaction and the binding geometry of the complex. The inner β-strand rich region of human TLR4 was calculated to be the most likely to accommodate the ATI molecule (Fig. 3, Panel A), with a predicted equilibrium dissociation constant of 9 × 10−8 M, in excellent agreement with the experimental results. Predictive ATI-TLR4 binding interface regions are shown in Fig. 3, Panel A, and amino acid sequences are presented in Fig. 3, Panel B.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional representation of the molecular docking of homology modelled wheat ATI CM3 (green ribbon) onto human TLR4-MD2 complex (grey ribbon). For better clarity of ATI-TLR4 complex visualization, MD2 molecule was removed after docking procedure. Black box highlights the oligopeptides constituting the discontinuous ATI binding interface. Oligopeptides are visualized as sticks (Panel A). Predicted cleavage sites by pepsin on wheat ATI CM3 (Panel B). The oligopeptides constituting the discontinuous ATI binding interface are highlighted in green. Residues constituting signal peptide (excluded from docking procedure) are highlighted in light blue.

Binding of ATI upon enzymatic digestion

Based on the results of docking and predictive protease cleavage sites studies, a minor portion of the discontinuous ATI binding interface was unaffected by pepsin treatment. The binding to TLR4 was tested also upon digestion of ATI with pepsin under both reducing and non-reducing conditions (Fig. 4), since native wheat ATIs are strongly stabilized by four intramolecular disulfide bonds, which confer resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis. As evident from the comparison of equilibrium dissociation constants, ATI largely preserved its binding ability upon digestion under non-reducing conditions (native ATI is strongly stabilized by four intramolecular disulfide bonds, which confer resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis), with a nearly 8-fold decrease in K D, exclusively attributable to the less favourable recognition phase (Table 2). Conversely, the digestion of ATI under reducing and acetylating conditions with 2-mercaptoethanol and iodoacetamide yielded a product still capable of binding to TLR4. This product displayed further lower affinity for TLR4 (nearly 43-fold lower than undigested ATI), both association and dissociation rates being significantly affected by the treatment.

Figure 4.

Binding of pepsin-digested ATI to surface-blocked TLR4. Comparison of responses obtained at increasing concentrations of the ATI digested under non-reducing (Panel A) and reducing conditions (Panel B).

Table 2.

Comparison of kinetic and equilibrium parameters of the interaction between TLR4 and both ATI (either non-digested and digested by pepsin) and the oligopeptide constituting part of the ATI binding interface.

| Complex | k ass (M−1 s−1) | k diss (s−1) | K D (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR4-ATI | 41000 ± 6000 | 0.0025 ± 0.0006 | (6.1 ± 1.7) × 10−8 |

| TLR4-ATInonred_dig | 6000 ± 400 | 0.0029 ± 0.0004 | (4.8 ± 0.7) × 10−7 |

| TLR4-ATIred_dig | 3000 ± 350 | 0.0077 ± 0.0010 | (2.6 ± 0.5) × 10−6 |

| TLR4-RSGNVGESGLI | 3620 ± 280 | 0.0050 ± 0.0012 | (1.4 ± 0.4) × 10−6 |

Competitive binding of a short ATI-derived peptide to TLR4

The results of computational analyses led to the identification of an oligopeptide (amino acid sequence: RSGNVGESGLI) constituting a significant portion of the discontinuous ATI binding interface to TLR4. This oligopeptide can largely escape pepsin digestion (the analysis of predictive protease cleavage sites with PeptideCutter26 evidenced the hydrolysis of only the last residue of the motif bearing the sequence of interest, as shown in Fig. 4), and (most importantly) is likely to antagonize ATI action by interfering with the formation of the ATI-TLR4 complex. In fact, according to molecular docking analysis with Autodock Vina, the peptide accommodated in a region of TLR4 constituting part of ATI binding interface: more specifically, Arg115 residue at the amino-terminal end of the RSGNVGESGLI peptide was predicted to interact with Asp379 present in TLR4, while Val119 of the oligopeptide is in contact with Tyr403 and Tyr451 residues of TLR4 (see Supplemental Material).

According to this premise, first we tested the ability of the oligopeptide to effectively bind to TLR4 using the same biosensor-based assay described above. The oligopeptide exhibited specific binding to the extracellular domain of TLR4 (Fig. 5, Panel A) with a 1:1 binding stoichiometry, (calculated as described above for the ATI-TLR4 complex). The equilibrium dissociation constant (K D,StrP = (1.4 ± 0.4) × 10−6 M) was compatible with the value measured upon binding between TLR4 and pepsin-digested ATI under reducing/alkylating conditions. Most interestingly, upon pre-saturation of TLR4 with 100 μM RSGNVGESGLI, the binding of ATI to the receptor was largely prevented, as evident from the corresponding 50% reduction in the maximal response at equilibrium (Fig. 5, Panel C). To address the specificity of the peptide–receptor interaction, a scrambled version of the peptide (amino acid sequence: SGIVLSGGNRE, generated using RandSeq tool27) was tested both for its binding ability to TLR4 and for competitive activity to ATI: the scrambled counterpart showed no competitive activity (Fig. 5, Panel C), still being capable of binding to the receptor although with lower affinity (K D,ScrP = 9.9 × 10−6 M) (Fig. 5, Panel B).

Figure 5.

Binding of ATI-derived oligopeptides to surface-blocked TLR4. Superimposition of sensorgrams obtained at increasing concentrations of the straight peptide (RSGNVGESGLI, Panel A), and of the scrambled counterpart (SGIVLSGGRNE, Panel B). Competitive binding to TLR4 (Panel C). Comparison of binding of ATI to free surface-blocked TLR4, and upon pre-saturation of the receptor with RSGNVGESGLI (#-marked curve) and with SGIVLSGGRNE (*-marked curve).

Discussions

Toll-like receptors are ubiquitous in immune cells28,29, in which they mediate the stimulation of the innate response and enhance adaptive immunity against pathogens30. In this context, their activation may result in the onset of autoimmune, chronic inflammatory and infectious diseases31. Specifically, nutritional ATI proteins from wheat were reported to activate the TLR4–MD2–CD14 complex15 according to a lipopolysaccharide-like mechanism, and elicit strong innate immune effects in vitro and in vivo, with consequent profound implications both in gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders (celiac disease, gluten sensitivity, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease), and in non-intestinal inflammation.

According to a concerted approach based on surface plasmon resonance biosensor and molecular docking methods, we explored the interaction between a representative member of the structurally conserved ATI family, namely CM3, and human TLR4, demonstrating ATI ability to directly target the receptor. The resulting 1:1 ATI-TLR4 complex was characterized by K D in the nanomolar range. ATI binding to TLR4 occurred with fully comparable affinity to that of TLR4 physiological partner MD232, and similar to other ATI targets, such as digestive serine proteases and amylases23. Additionally, wheat ATI CM3 preserved part of the native TLR4-binding ability upon in vitro enzymatic digestion, confirming the role of intramolecular disulphide bonds as key determinants of wheat ATI capacity to survive gastro-intestinal transit and trigger TLR4 signalling25.

ATI-TLR4 complex was mainly stabilized by non-covalent electrostatic interactions, and changes in ionic strength significantly altered the dissociation rate and the stability of the complex. Specifically, k diss and K D values increased nearly by a 25-fold factor in the presence of NaCl (up to 140 mM), as determined by analogous biosensor-based binding assays replicated under different ionic strength conditions, and in agreement with the results of the computational mapping of electrostatic potentials (see Fig. 2 and Supplemental Material).

Consistently with these experimental evidences, computational analysis predicted ATI molecule to favourably accommodate within the β-strand loop of TLR4, in a binding region distinct from both MD2 and TLR4 self-dimerization interfaces33. The full agreement between computational and experimentally determined equilibrium dissociation constants confirmed the quality of the predictive model.

Other works exploited the minimal binding region between TLR4 and a number of physiological binders thereof (MD234, MyD8835, and TRAM36) to prevent complex formation and inflammatory downstream effects. Analogously, the mapping of the binding interfaces of TLR4-ATI model (Fig. 3) was pivotal in guiding the design and the synthesis of an antagonist 11-mer oligopeptide (largely hydrolase-resistant, as predicted by sequence analysis). Preliminary docking studies predicted the binding interface between the 11-mer and TLR to be perfectly superimposable to that of ATI (see Supplemental Material); when tested for binding to TLR4, the oligopeptide specifically bound to the receptor with partly preserved binding affinity of the parent ATI molecule, but most interestingly successfully prevented the formation of the ATI-TLR4 complex in a biosensor-based competitive binding assay. Based on these promising results, we reasonably believe that this oligopeptide could inhibit the activation of ATI-induced inflammatory cascade, consistently with previous studies reporting the abrogation of IL-1β production upon treatment with ATI digested under reducing and alkylating conditions37.

In conclusion, our findings may have physiological and pharmacological implications not only for celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity, but also for other gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders. Furthermore, although demanding further customization (at this stage, the nearly 30-fold lower affinity and slower association kinetics with respect to ATI would require a large excess of the oligopeptide to interfere with the interaction with TLR4) the RSGNVGESGLI peptide can be used as the starting point for the rational design of ligands able to specifically block the interaction between TLR4 and its activators. Further studies are currently in progress.

Methods

Biosensor device

Binding experiments were performed on an evanescent wave/resonant mirror38 optical biosensor (IAsys plus - Affinity Sensors Ltd, Cambridge, UK), equipped with dual-well carboxylate cuvettes (NeoSensors, Ltd., UK). A working volume of 80 μL was used throughout, and the temperature was set at 37 °C. The possible influence of mass transport on the determination of kinetic parameters39 was considered and reduced by setting the stirrer rate to 95%.

Preparation of TLR4 surface

TLR4-functionalized surfaces were obtained following a previously reported protocol23. Briefly, carboxylate cuvettes were rinsed and equilibrated with PBS pH 7.4, and carboxylic groups were activated by EDC/NHS chemistry40. TLR4-His was solubilized in 10 mM CH3COONa, pH 4.5, then covalently coupled to the carboxylic surface via the N-terminus of the poly-His tail. To optimize surface density, different stock solutions of TLR4-His with concentrations in the range 200–1000 μg/mL were tested: 400 μg/mL was finally selected as it minimized steric hindrance, and at the same time prevented the dimerization between blocked TLR4-His macromolecules, both events being likely to reduce the number of available binding sites on the sensing surface. Free carboxylic sites on the sensor surface were inactivated by treatment with 1 M ethanolamine, pH 8.5. The surface was finally re-equilibrated with PBS.

The resulting shifts in the baseline (ΔR = 700–800 arcsec) generally indicated the assembly of a partial receptor monolayer for a 100 kDa protein (approximately 70% surface occupancy) corresponding to a final surface density of 1.20–1.30 ng/mm2, approximately equivalent to 9–10 mg/mL.

The use of CH3COONa 10 mM, pH 4.5 as immobilization buffer (chosen on the basis of TLR4-His isoelectric point 5.88) allowed an efficient immobilization. Negative baseline drift signals in TLR4 surface were not observed with time or upon multiple washes, confirming that the receptor molecules were irreversibly linked to the sensor surface.

Determination of kinetic and equilibrium constants

Wheat ATI CM3 was added at six different concentrations in the range 16–600 nM to the TLR4 surface, each time monitoring association kinetics to equilibrium (approximately 2–4 min, depending on the concentration of ATI) prior to start dissociation phase.

Dissociation steps were performed with a single wash with PBS buffer, whereas baseline recovery was achieved by multiple washes with PBS supplemented with 200 mM NaCl, as ionic strength decreased the stability of the complex without affecting the functionality of the surface.

The determination of rate and equilibrium parameters was performed as described in detail elsewhere41. Briefly, upon addition of soluble ATI to surface-blocked TLR4, the amount of the ATI-TLR4 complex formed in time t, is given by:

| 1 |

where [ATI − TLR4]eq is the concentration of complex at equilibrium. k on is the concentration-dependent, pseudo-first order rate constant for the interaction where:

| 2 |

The instrumental response is proportional to the mass of bound ligand, resulting in:

| 3 |

where R t is the response at time t, R 0 is the initial response, and R eq the maximal response at equilibrium for a given ligand concentration. From the fit of raw data, k on values can be determined at any given concentration of ligand.

Hence, k ass and k diss were derived from the k on vs ATI concentration plot. Equilibrium dissociation constant values were obtained both from the ratio of kinetic constants (K D = k diss/k ass), and from the extent of the binding measured at equilibrium for any ligand concentration. In fact:

| 4 |

where R max is the response at equilibrium obtained at asymptotic concentration of ligand. Once a complex has been formed, it will eventually dissociate into its components. Usually, the dissociation of surface-bound complexes may be described by:

| 5 |

A is the extent of the dissociation phase. Binding analyses were repeated under different conditions to assess the influence of pH and ionic strength on the interaction (in the range of pH between 6 and 8, and salt concentration between 20 and 140 mM, respectively).

Raw binding data were analysed using the Fast Fit software (Fison Applied Sensor Technology) as previously reported42: the software uses an iterative curve-fitting to derive the observed rate constant and the maximum response at equilibrium due to ligand binding at a particular ligand concentration. Local and global fit analysis of the interaction data generally revealed monophasic kinetics. Specifically, mono-exponential analysis of association curves residuals was not affected by measurable systematic errors (a bi-exponential model did not significantly improve the quality of the fit as judged by an F-test, 95% confidence).

As a proof of specificity, wheat ATI produced non-significant signal upon addition to a bare carboxylate surface.

Prediction of three-dimensional structure of wheat ATI

ATI CM3 precursor protein query sequence (P17314.143) was obtained from UniProt database. The signal peptide (MACKSSCSLLLLAVLLSVLAAASA) was predicted using SignalP44, and the N-terminus sequence shortened accordingly. Fold-recognition was performed using I-Tasser45, the best structural templates being: 1B1U46, 4CVW47, 1BEA48, 1BFA48. The best predicted model had a TM-Score of 0.67 ± 0.13 (TM-score > 0.5 indicates a model of correct topology49). The model was refined and validated with Chiron-Gaia50,51.

Protein-protein docking analysis

The predictive model of the complex between wheat ATI CM3 (UniProtKB ID: P17314) and human TLR4 was computed by docking ATI CM3 (obtained by fold-recognition) onto the crystallographic structure of the receptor (PDB ID: 3FXI33). Rigid docking was performed using PatchDock server52,53, ATI CM3 and TLR4 being uploaded as ligand and receptor, respectively, and FireDock54,55 was used for interaction refinement. Settings were always kept to default values. The best scoring complex and all images were rendered with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3 Schrödinger, LLC).

Protein-peptide docking analysis

The most probable binding site for RSGNVGESGLI oligopeptide on human TLR4 (PDB ID: 3FXI33) was identified by flexible docking using the Autodock Vina software (version 1.1.2)56 on an Intel Core i7/Mac OSX 10.12-based platform. Hydrogen atoms were added to the receptor protein prior to any analysis. RSGNVGESGLI peptide was designed and energy minimized using Avogadro57 (Force field: MMFF94; Number of steps: 500; Algorithm: Conjugate gradients; Convergence: 10−7). Autodock Vina (a software performing a Lamarckian genetic algorithm to explore the binding possibilities of a ligand in a binding pocket58) was used with a grid of 76, 70, and 65 Å (in the x, y, and z directions) around the receptor, with a grid spacing of 0.375 Å, a root-mean-square (rms) tolerance of 0.8 Å, and a maximum of 2,500,000 energy evaluations. Other parameters were set to default values59. The obtained model has been further refined using NNScore60.

Calculation of electrostatic potential maps

Electrostatic potential maps were determined using PDB2PQR server61 (including the APBS web solver), uploading the three-dimensional structures, and setting the parameters as default (Force field: PARSE). PROPKA was used for the determination of pKa.

ATI digestion using pepsin under reducing conditions

ATI was treated in sequence with 2% 2-mercaptoethanol (10 min at 25 °C) to reduce intramolecular disulfide bonds, and with 14 mM iodoacetamide (30 min at 25 °C) to prevent re-oxidation of the thiols62. Resulting sample was extensively dialyzed against 20 mM sodium acetate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 4.0 to remove 2-mercaptoethanol and iodoacetamide, and eventually digested with pepsin according to the method described by Lin et al.63. Briefly, ATI was incubated with pepsin at 4 °C for 48 h, and the reaction was blocked by neutralization (pH = 7) with NaOH. The hydrolysis product was processed for binding to surface-blocked TLR4 as described above.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation of results obtained from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni test using Sigma-stat 3.1 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). p values < 0.01 were considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Author Contributions

M.C. designed, performed, analyzed the biosensor data; wrote the manuscript. M.A. supervised the project, performed the design of the RSGNVGESGLI peptide, performed peptide docking to TLR4, interpreted the results. S.I.S. designed and produced the pEF-BOS TLR4 plasmid. M.F. and M.G. expressed and purified the pEF-BOS TLR4 plasmid in Escherichia coli. V.C., L.B. and A.M.E. optimized and produced the plasmid transfection in competent HCT-116 cell line. M.M. performed the fold-recognition of ATI, and the ATI docking to TLR4, together with the electrostatic potential maps.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-13709-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brant A. Baker’s asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:152–155. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328042ba77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fasano A, Sapone A, Zevallos V, Schuppan D. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1195–1204. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catassi C, et al. Diagnosis of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS): The Salerno Experts’ Criteria. Nutrients. 2015;7:4966–4977. doi: 10.3390/nu7064966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catassi C, et al. Non-Celiac Gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients. 2013;5:3839–3853. doi: 10.3390/nu5103839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis A, Linaker BD. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity? Lancet. 1978;1:1358–1359. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)92427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuppan D, Junker Y, Barisani D. Celiac disease: from pathogenesis to novel therapies. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1912–1933. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson A, MacDonald TT, McClure JP, Holden RJ. Cell-mediated immunity to gliadin within the small-intestinal mucosa in coeliac disease. Lancet. 1975;1:895–897. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)91689-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pietzak M. Celiac disease, wheat allergy, and gluten sensitivity: when gluten free is not a fad. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36:68S–75S. doi: 10.1177/0148607111426276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sollid LM, Jabri B. Triggers and drivers of autoimmunity: lessons from coeliac disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:294–302. doi: 10.1038/nri3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tatham AS, Shewry PR. Allergens to wheat and related cereals. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1712–1726. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuppan D, Zevallos V. Wheat amylase trypsin inhibitors as nutritional activators of innate immunity. Dig Dis. 2015;33:260–263. doi: 10.1159/000371476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludvigsson JF, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 2013;62:43–52. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroccio, A. et al. Non-celiac wheat sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo-controlled challenge: exploring a new clinical entity. Am J Gastroenterol107, 1898–1906; quiz 1907 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Fitzgerald KA, et al. LPS-TLR4 signaling to IRF-3/7 and NF-kappaB involves the toll adapters TRAM and TRIF. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;198:1043–1055. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Junker Y, et al. Wheat amylase trypsin inhibitors drive intestinal inflammation via activation of toll-like receptor 4. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209:2395–2408. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupont FM, Vensel WH, Tanaka CK, Hurkman WJ, Altenbach SB. Deciphering the complexities of the wheat flour proteome using quantitative two-dimensional electrophoresis, three proteases and tandem mass spectrometry. Proteome Sci. 2011;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan CA. Protease Inhibitors in Plants: Genes for Improving Defenses Against Insects and Pathogens. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 1990;28:425–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.28.090190.002233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makharia A, Catassi C, Makharia GK. The Overlap between Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: A Clinical Dilemma. Nutrients. 2015;7:10417–10426. doi: 10.3390/nu7125541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frazer AC, et al. Gluten-induced enteropathy: the effect of partially digested gluten. Lancet. 1959;2:252–255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(59)92051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oda Y, Matsunaga T, Fukuyama K, Miyazaki T, Morimoto T. Tertiary and quaternary structures of 0.19 alpha-amylase inhibitor from wheat kernel determined by X-ray analysis at 2.06 A resolution. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13503–13511. doi: 10.1021/bi971307m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo G, et al. Proteome characterization of developing grains in bread wheat cultivars (Triticum aestivum L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finnie C, Melchior S, Roepstorff P, Svensson B. Proteome analysis of grain filling and seed maturation in barley. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1308–1319. doi: 10.1104/pp.003681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuccioloni M, et al. Interaction between wheat alpha-amylase/trypsin bi-functional inhibitor and mammalian digestive enzymes: Kinetic, equilibrium and structural characterization of binding. Food Chem. 2016;213:571–578. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tilg H, Koch R, Moschen AR. Proinflammatory wheat attacks on the intestine: alpha-amylase trypsin inhibitors as new players. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1561–1563. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zevallos VF, et al. Nutritional Wheat Amylase-Trypsin Inhibitors Promote Intestinal Inflammation via Activation of Myeloid Cells. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1100–1113 e1112. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gasteiger, E. et al. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. (Humana Press, 2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Gasteiger E, et al. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3784–3788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hornung V, et al. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–4537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muzio M, et al. Differential expression and regulation of toll-like receptors (TLR) in human leukocytes: selective expression of TLR3 in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:5998–6004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook DN, Pisetsky DS, Schwartz DA. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human disease. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:975–979. doi: 10.1038/ni1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han J, et al. Structure-based rational design of a Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) decoy receptor with high binding affinity for a target protein. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park BS, et al. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature. 2009;458:1191–1195. doi: 10.1038/nature07830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slivka PF, et al. A peptide antagonist of the TLR4-MD2 interaction. Chembiochem. 2009;10:645–649. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hines DJ, Choi HB, Hines RM, Phillips AG, MacVicar BA. Prevention of LPS-induced microglia activation, cytokine production and sickness behavior with TLR4 receptor interfering peptides. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piao W, Vogel SN, Toshchakov VY. Inhibition of TLR4 signaling by TRAM-derived decoy peptides in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2013;190:2263–2272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palova-Jelinkova L, et al. Pepsin digest of wheat gliadin fraction increases production of IL-1beta via TLR4/MyD88/TRIF/MAPK/NF-kappaB signaling pathway and an NLRP3 inflammasome activation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cush, R., Cronin, J. M., Stewart, W. J., Maule, C. H. & Molloy, J. The resonant mirror: a novel optical biosensor for direct sensing of biomolecular interactions Part I: principle of operation and associated instrumentation. Biosens Bioelectron, 347–354 (1993).

- 39.Muhonen WW, Shabb JB. Resonant mirror biosensor analysis of type Ialpha cAMP-dependent protein kinase B domain–cyclic nucleotide interactions. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2446–2456. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.12.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards PR, Lowe PA, Leatherbarrow RJ. Ligand loading at the surface of an optical biosensor and its effect upon the kinetics of protein-protein interactions. J Mol Recognit. 1997;10:128–134. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1352(199705/06)10:3<128::AID-JMR357>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cuccioloni M, et al. Kinetic and equilibrium characterization of the interaction between bovine trypsin and I-ovalbumin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1702:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cuccioloni M, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate potently inhibits the in vitro activity of hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:897–907. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M011817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Maroto F, Marana C, Mena M, Garcia-Olmedo F, Carbonero P. Cloning of cDNA and chromosomal location of genes encoding the three types of subunits of the wheat tetrameric inhibitor of insect alpha-amylase. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;14:845–853. doi: 10.1007/BF00016517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang J, et al. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat Methods. 2015;12:7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gourinath S, Alam N, Srinivasan A, Betzel C, Singh TP. Structure of the bifunctional inhibitor of trypsin and alpha-amylase from ragi seeds at 2.2 A resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:287–293. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999016601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moller MS, et al. Crystal structure of barley limit dextrinase-limit dextrinase inhibitor (LD-LDI) complex reveals insights into mechanism and diversity of cereal type inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:12614–12629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.642777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Behnke CA, et al. Structural determinants of the bifunctional corn Hageman factor inhibitor: x-ray crystal structure at 1.95 A resolution. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15277–15288. doi: 10.1021/bi9812266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Skolnick J. Scoring function for automated assessment of protein structure template quality. Proteins. 2004;57:702–710. doi: 10.1002/prot.20264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kota P, Ding F, Ramachandran S, Dokholyan NV. Gaia: automated quality assessment of protein structure models. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2209–2215. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramachandran S, Kota P, Ding F, Dokholyan NV. Automated minimization of steric clashes in protein structures. Proteins. 2011;79:261–270. doi: 10.1002/prot.22879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneidman-Duhovny D, Inbar Y, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W363–367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duhovny, D., Nussinov, R. & Wolfson, H. J. In Proceedings of the 2’nd Workshop on Algorithms in Bioinformatics (WABI). (ed Gusfield et al.) 185–200 (Springer Verlag).

- 54.Andrusier N, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. FireDock: fast interaction refinement in molecular docking. Proteins. 2007;69:139–159. doi: 10.1002/prot.21495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mashiach E, Schneidman-Duhovny D, Andrusier N, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. FireDock: a web server for fast interaction refinement in molecular docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W229–232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hanwell MD, et al. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J Cheminform. 2012;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morris GM, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mozzicafreddo M, Cuccioloni M, Cecarini V, Eleuteri AM, Angeletti M. Homology modeling and docking analysis of the interaction between polyphenols and mammalian 20S proteasomes. J Chem Inf Model. 2009;49:401–409. doi: 10.1021/ci800235m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Durrant JD, McCammon JA. NNScore: a neural-network-based scoring function for the characterization of protein-ligand complexes. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:1865–1871. doi: 10.1021/ci100244v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dolinsky TJ, Nielsen JE, McCammon JA, Baker NA. PDB2PQR: an automated pipeline for the setup of Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W665–667. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Papandreou MJ, Idziorek T, Miquelis R, Fenouillet E. Glycosylation and stability of mature HIV envelope glycoprotein conformation under various conditions. FEBS Lett. 1996;379:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01505-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin LC, Putnam FW. Cold pepsin digestion: a novel method to produce the Fv fragment from human immunoglobulin M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:2649–2653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.