Abstract

Global brain ischemia can lead to widespread neuronal death and poor neurologic outcomes in patients. Despite detailed understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms mediating neuronal death following focal and global brain hypoxia-ischemia, treatments to reduce ischemia-induced brain injury remain elusive. One pathway central to neuronal death following global brain ischemia is mitochondrial dysfunction, one consequence of which is the cascade of intracellular events leading to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. A novel approach to rescuing injured neurons from death involves targeting cellular membranes using a class of synthetic molecules called Pluronics. Pluronics are triblock copolymers of hydrophilic poly[ethylene oxide] (PEO) and hydrophobic poly[propylene oxide] (PPO). Evidence is accumulating to suggest that hydrophilic Pluronics rescue injured neurons from death following substrate deprivation by preventing mitochondrial dysfunction. Here, we will review current understanding of the nature of interaction of Pluronic molecules with biological membranes and the efficacy of F-68, an 80% hydrophilic Pluronic, in rescuing neurons from injury. We will review data indicating that F-68 reduces mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondria-dependent death pathways in a model of neuronal injury in vitro, and present new evidence that F-68 acts directly on mitochondria to inhibit mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. Finally, we will present results of a pilot, proof-of-principle study suggesting that F-68 is effective in reducing hippocampal injury induced by transient global ischemia in vivo. By targeting mitochondrial dysfunction, F-68 and other Pluronic molecules constitute an exciting new approach to rescuing neurons from acute injury.

Keywords: Poloxamer 188, STORM super resolution microscopy, apoptosis, MOMP, hippocampal neurons

1. Introduction

Mammalian forebrain neurons are exquisitely vulnerable to ischemia, which results in cellular deprivation of metabolic substrates and oxygen, termed hypoxia-ischemia (HI)1. Focal brain HI, or stroke, arises from occlusion of an artery perfusing part of the brain, and can result in severe disability, depending on which brain regions have been affected. Global brain HI occurs during conditions of decreased perfusion to the entire forebrain, of which the most common causes are cardiac arrest in adults (Go et al., 2012) and perinatal asphyxia in children. Global brain HI can lead to widespread neuronal death and poor neurologic outcomes in 50% of adult survivors and to cerebral palsy and global developmental delay in infants. Despite detailed understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms mediating neuronal death following focal and global brain hypoxia-ischemia (HI), clinical treatments to reduce HI-induced brain injury remain limited to thrombolysis for the former (Albers et al., 2011) and brain hypothermia for the latter (Hypothermia after Arrest Study Group, 2002; Jacobs et al., 2007).

Increasing evidence has identified the family of synthetic Pluronic molecules as a novel approach to rescuing neurons following acute injury, including after acute substrate deprivation. Here, we will review the properties of Pluronics, and present published and new evidence that hydrophilic Pluronics rescue neurons from substrate-deprivation-induced death through actions on membranes, in particular those of mitochondria. All animal studies presented here were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals.

2. Pluronic-mediated cellular rescue from injury: State of the Art

2.1 The Pluronic molecule

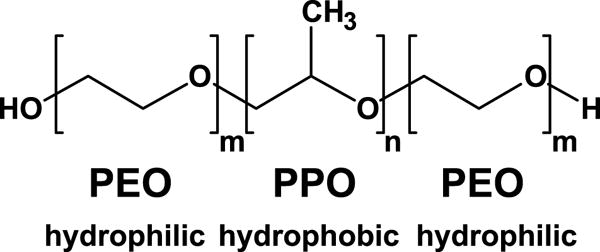

Pluronics (Alexandridis and Hatton, 1994) are synthetic co-polymers of poly[ethylene oxide] (PEO) and poly[propylene oxide] (PPO), synthesized in a PEOm-PPOn-PEOm configuration, where m and n denote the number of monomers in a block (Fig. 1). The PPO chain, by virtue of the methyl group on each monomer, is hydrophobic compared with the hydrophilic PEO chains. The members of the Pluronic family differ from one another in the lengths of the PEO and PPO chains and thus their relative hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity. The presence of a hydrophobic block between two hydrophilic blocks makes these tri-block co-polymers amphiphilic, and they are soluble in a variety of aqueous and organic solvents. Amphiphilicity confers upon Pluronics the property of interacting with lipid membranes. Importantly, these nonionic compounds are without reactive groups, save for the chain-end hydroxyl groups. At concentrations lower than the temperature-dependent critical micellar concentration (CMC), Pluronics exist as unimers and gyrate through size-dependent hydrodynamic radii (Alexandridis and Hatton, 1994). At concentrations above the CMC, unimers begin to form micelles. At progressively higher concentrations, gels and other more compacted structures form (Alexandridis and Hatton, 1994).

Figure 1. Structure of the Pluronic family of tri-block co-polymers.

Amphiphilic Pluronics are symmetrical co-polymers of poly[ethylene oxide] (PEO) and poly[propylene oxide] (PPO), such that hydrophilic PPO chains of equal length (m) surround a hydrophobic PPO chain of another length (n).

Pluronic F-68 (F-68) is an 80% hydrophilic Pluronic, having the composition PEO76-PPO29-PEO76 (8600 kDa), and has been employed in multiple studies of its cellular protection properties. At 37° C, the reported CMC of F-68 has been variably reported across two orders of magnitude: from 125 μM (Maskarinec et al., 2002), to 1.1 mM (Batrakova et al., 1998), to as high 8 mM (Alexandridis et al., 1994). This wide range has likely depended on the method employed and the polydispersity of the compound studied. Notably, unimeric Pluronics form neither ionic nor covalent bonds with other molecules and thus, Pluronic-membrane interactions are weak.

F-68 interactions with giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs), a model membrane system, have been recently characterized with 1H- Overhauser dynamic nuclear polarization-enhanced NRM spectroscopy, a novel approach to measuring the dynamics of water diffusion through the 10–20 Å thick hydration layer at the surface of a lipid membrane(Franck et al., 2013). This study revealed that F-68 progressively decreases surface water diffusivity as a function of concentration up to the CMC, demonstrating Pluronic adsorption to the membrane surface. Comparison with PEO-only polymers demonstrates that the hydrophobic PPO block of F-68 plays an essential role in driving F-68 to effectively interact with the membrane surface (Cheng et al., 2012).

2.2 F-68 as a membrane sealant: cellular and model vesicle studies

Initial studies of the interaction of hydrophilic Pluronics with membranes focused on the plasma membrane. F-68 was first reported to restore plasma membrane integrity in electroporated skeletal muscle cells (Lee et al., 1992). Similarly, in cardiac myocytes of dystrophin-deficient mice, a model of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy in which stretching of cardiac myocytes disrupts sarcolemma integrity and decreases contractility, F-68 restores sarcolemmal integrity and improves cardiac contractility in vitro and in vivo (Yasuda et al., 2005). In in vitro models of traumatic brain injury, F-68 prevents fluid shear stress-induced axonal beading, a morphological hallmark of diffuse axonal injury (Kilinc et al., 2007; Kilinc et al., 2009), and inhibits trauma induced plasma membrane disruption (Serbest et al., 2005a; Serbest et al., 2005b).

Neurons die following HI through multiple mechanisms, including excitotoxicity-induced, calcium-dependent activation of multiple intracellular processes, increased production of reactive oxygen species, membrane lipid peroxidation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Since the seminal publications by Ankarcona et al. (1995) and Bonfoco (1995), the nature of excitotoxic neuronal death has been recognized to depend on the severity of the insult (Ankarcrona et al., 1995) and the subsequent mitochondrial response (Bonfoco et al., 1995), such that severe insults result in necrosis and less severe insults lead to activation of forms (Green, 2016) of programmed cell death.

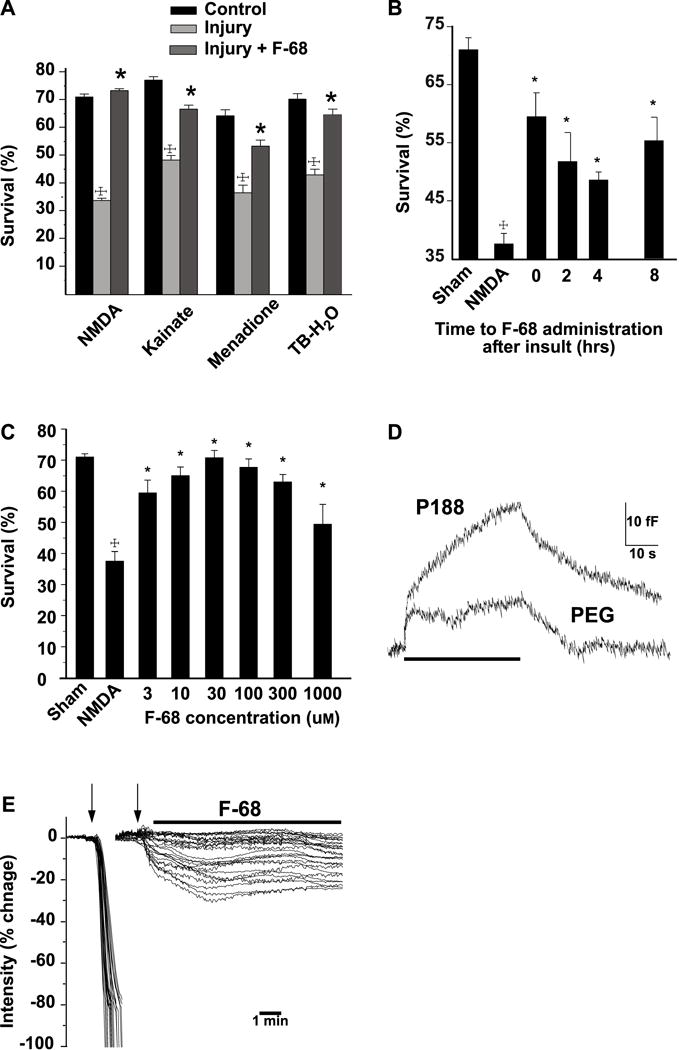

The early findings that F-68 acted on the plasma membrane prompted us initially to ask whether F-68 could reduce neuronal injury following insults resulting in, presumably, necrosis and loss of plasma membrane integrity (Marks et al., 2001). Using cultured embryonic (E18.5) rat hippocampal neurons, we induced neuronal injury using brief (15 min) exposures to stimuli known to induce mechanisms of neuronal death following HI. Specifically, we used high concentrations of N-methyl-D-aspartate (300 μm), kainate (100 μm), menadione (30 μm, a generator of superoxide), or tert-butyl-hydroperoxide (100 μm, to induce lipid peroxidation), and added F-68 to neurons after the exposure had been completed (Fig. 2A). Each of these stimuli reduced neuronal survival to about 40%. After 48 hrs of incubation, F-68 provided near-complete neuronal rescue from each of these insults, in a dose-dependent manner, such that efficacy peaked at 30 μm, decreasing at higher concentrations (Fig. 2C). This decreased efficacy of F-68 at higher concentrations is most simply explained by the formation of co-polymer micelles near its temperature-dependent CMC and removal of co-polymers from the bulk phase, although concentration-dependent effects may not be clarified at this level of endpoints. Importantly, delaying addition of F-68 to neurons for up to eight hours after injury still produced significant neuronal rescue (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. F-68 rescues cultured neurons from stimuli mediating neuronal death from hypoxia-ischemia.

A. Mean neuronal survival (± SEM) 48 h following intense excitotoxic (NMDA, kainate) and oxidative (menadione, terf-butyl-hydroperoxide) insults resulting in necrosis. Hippocampal neurons were used for all stimuli except kainate (100 μM), when cultured embryonic cerebellar Purkinje neurons were used. Statistical significance between groups (†P<0.0001, toxin treatment vs. control; * P<0.001, toxin with F-68 vs. toxin alone) determined with the likelihood ratio test (with correction for multiple comparisons) following overall significance by logistic regression. B. Survival of hippocampal neurons following NMDA and increasing delays between NMDA and addition of F-68 to the cultures (†P<0.0001, NMDA vs. control *P<0.001, F-68 vs NMDA). C. Mean neuronal survival (± SEM) of hippocampal neurons 48 hrs following NMDA (300 μM for 15 min), followed by different concentrations of F-68 in the media. Sham represents 15-min incubation in HEPES-buffered saline. Statistical significance between groups (†P<0.001, NMDA vs. control; *P<0.001, NMDA vs control) determined as in (B) above. D. Increases in whole-cell capacitance by F-68 and PEG. Superimposed traces of continuous changes in capacitance over time of bovine adrenal chromaffin cells in response to perfusion (bar) of F-68 (100 μM) and PEG (mw 8,400 100 μM). Baseline capacitance is 5.1 ± 0.28 pF (SEM, n=8). Traces have been superimposed so that baseline capacitance values and stimulation onsets overlap. E. F-68 arrests electroporation-induced loss of intracellular contents. Montage of superimposed plots of electroporation-induced changes in intracellular calcein fluorescence of hippocampal neurons in the presence (right) and absence (left) of F-68 (100 μM, bar). Electroporation train (5 Hz, 1 s) delivered at arrows. For each cell, fluorescence change is plotted as a percentage of baseline. Copyright The FASEB Journal. Reproduced with permission.

To better understand whether F-68 interacted with the plasma membrane, we applied F-68 to bovine adrenal chromaffin cells, and measured induced changes of membrane capacitance, a sensitive probe of plasma membrane surface area (Augustine and Neher, 1992; Neher and Marty, 1982). We used poly(ethylene) oxide (PEG, 8,000 Da) as a control polymer of similar molecular weight, which cannot insert into membranes. F-68 (30 μm) increased whole cell capacitance significantly more than PEG (Fig. 2D), indicating that F-68 increased membrane surface area, perhaps by having inserted into the plasma membrane. Finally, application of F-68 to neurons immediately after electroporation, prevented loss of intracellular dye through electro-pores (Fig. 2E). These latter observations were consistent with the prevailing idea that F-68 inserted into damaged plasma membrane and restored plasma membrane integrity through membrane sealing (Lee et al., 1993; Lee et al., 1992; Mina et al., 2009; Ng et al., 2008; Terry et al., 1999; Yasuda et al., 2005).

To directly determine the interaction of F-68 with the plasma membrane, we employed fluorescent dye-loaded GUVs, (made up of POPC, POPG, Biotin-PE, and Texas Rd-tagged DHPE in 88/10/1/1 mol ratio) as a highly-reduced model of the plasma membrane, and induced loss of membrane integrity with hypo-osmotic stress (Wang et al., 2010). When incubated in hypo-osmolar solutions, GUVs initially swelled elastically, and then demonstrated dye leakage through membrane pores induced by decreased lipid packing density in response to swelling. In the presence of F-68 (50 μm), the period of elastic swelling was increased (Wang et al., 2010). However, F-68 failed to block or significantly inhibit dye leakage (Wang et al., 2010), suggesting that a simple model of plasma membrane sealing is inadequate to explain the neuronal rescue properties of F-68.

2.3 F-68 inhibits apoptosis following acute substrate deprivation

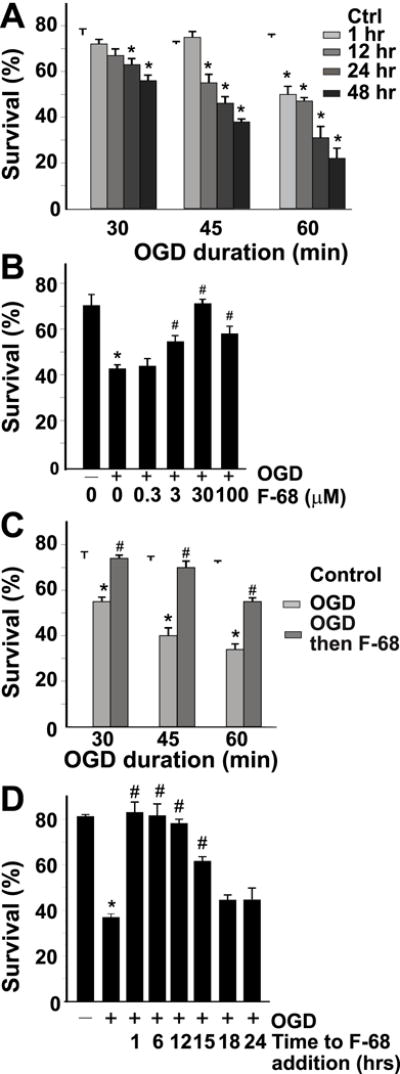

Because F-68 rescued cultured hippocampal neurons following induction of mechanisms contributing to neuronal death, we determined its efficacy in rescuing neurons following severe oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD), a widely used in vitro model of HI-induced brain injury. In this paradigm (30–60 min of exposure to glucose-free, bicarbonate-buffered solutions equilibrated with 1% O2), neurons die stochastically over 48 hrs to an extent determined by the duration of OGD (Fig. 3A). Death following OGD was prevented by caspase inhibitors, and preceded by Annexin V and TUNEL staining in the majority of neurons, demonstrating that OGD-induced death via apoptosis (Shelat et al., 2013). Incubation of neurons in F-68 (300 nm–100 μm) for 48 hrs after OGD rescued neurons from death in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B) with complete rescue occurring following 30 or 45 min OGD with 30 μm F-68 (Fig. 3C). Following 60 min OGD, F-68 (30 μm) rescued all neurons that had not died within an hour of insult (Fig. 3C). Thus, F-68 profoundly inhibits OGD-induced apoptosis. In addition, the number of neurons exhibiting TUNEL and Annexin V staining were not significantly different in F-68 treated neurons following OGD from those in control neurons (Shelat et al., 2013).

Figure 3. F-68 rescues cultured hippocampal neurons from OGD.

A. Mean neuronal survival (± SD) over time after 30, 45, and 60 min of OGD. B. Mean neuronal survival (± SD) 48 hrs after OGD of different durations in the presence and absence of F-68 (30 μm) C. Concentration dependence of F-68–induced rescue of neurons after 45 min OGD, measured 48 h later. D. Mean neuronal survival (± SD) following OGD (45 min) with increasing delay in F-68 (30 μm) addition after OGD. Survival measured 48 h after OGD Note that neuronal rescue from OGD persists when F-68 addition is delayed as much as 12–15 h after OGD. Copyright The Journal of Neuroscience. Reproduced with permission.

Importantly, F-68 induced rescue was equally effective when administration was delayed as long as 12 hrs after insult (Fig. 3D). As we observed cleavage of fluorescent caspase substrates six hrs after OGD in neurons not treated with F-68 (Shelat et al., 2013), this late rescue raised the possibility that F-68 overcame early caspase activation. Indeed, following OGD exposure, delay of F-68 treatment for 12 hrs returned the number of caspase activation-positive neurons to control levels (Shelat et al., 2013).

2.4 F-68 acts on mitochondria to inhibit OGD-induced apoptosis

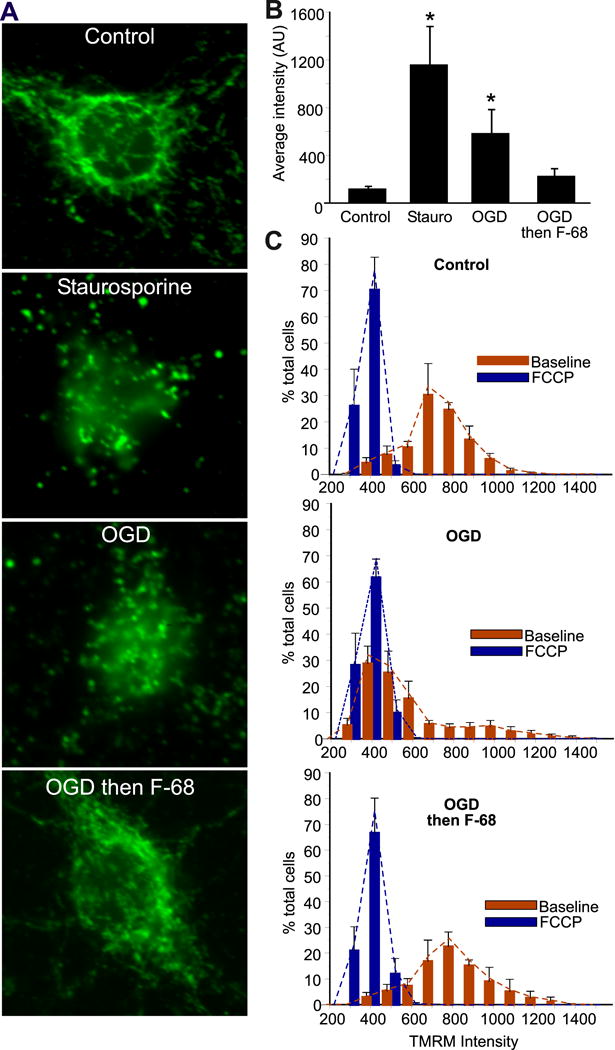

In vitro, neuronal apoptosis following substrate deprivation occurs via the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Ma et al., 2013; Wiessner et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2013). This pathway is characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction (Luo et al., 2013) and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm, Zhao et al., 2013), decreased mitochondrial outer membrane permeability (Zhao et al., 2014), and release of mitochondrial pro-apoptotic factors, including cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor, and others into the cytosol (Munoz-Pinedo et al., 2006). Because F-68 treatment rescued neurons from OGD-induced apoptosis, we asked whether F-68 acted on this mitochondrial pathway. Fluorescent imaging of individual, TMRM-loaded neurons six hrs after OGD, in the presence and absence of F-68, demonstrated that F-68 prevented both the OGD-induced cytochrome c release (Fig. 4A, 4B) and Δψm dissipation (Fig. 4C), returning both to control levels. This was the first evidence that F-68 blocks OGD-induced mitochondrial apoptosis (Shelat et al., 2013).

Figure 4. F-68 prevents OGD-induced release of mitochondrial cytochrome c and dissipation od mitochondrial membrane potential.

A. Cellular distribution of cytochrome c immunoreactivity 6 h after staurosporine (1 nm) or 45 min exposure to OGD with or without F-68 (30 μm). Scale bar, 10 μm. B.

Mean intensities (± SD) of fluorescent cytochrome c immunoreactivity over the nuclear volume at baseline and 6 hr after staurosporine (positive control), OGD (45 min) or OGD (45 min) followed by F-68 (30 μm). #P<0.0001; *P<0.01. C. Histograms of individual neuronal TMRM intensities (red bars) 6 h after OGD or control, and in the same cells after FCCP (blue bars) to dissipate mitochondrial membrane potential. Copyright The Journal of Neuroscience. Reproduced with permission.

The F-68-induced blockade of mitochondrial apoptosis suggested that F-68 may act on mechanisms leading to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP). MOMP is regulated by Bcl-2 protein family members (Perera et al., 2012). Onset of OMM permeabilization occurs when anti-apoptotic BCL2 proteins (including Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 and Mcl-1) are sufficiently inhibited by BH3-only proteins (including BIM, PUMA, NOXA, and BAD) to allow recruitment of BAX to the OMM and activation of it and its homolog, BAK, in the OMM (Hardwick and Soane, 2013). Activation of these multi-BH domain-containing effector proteins is followed by their association into pore-associated oligomers and OMM permeabilization (Iyer et al., 2016). In neurons, which express a BH3-only splice variant of BAK, termed N-BAK (Sun et al., 2001), the role of BAK in ischemia-induced neuronal death may be limited to its dissocation from the mitofusin Mfn-2 to induce mitochondrial fragmentation (Brooks et al., 2007) or, in some injury models, be protective (Fannjiang et al., 2003).

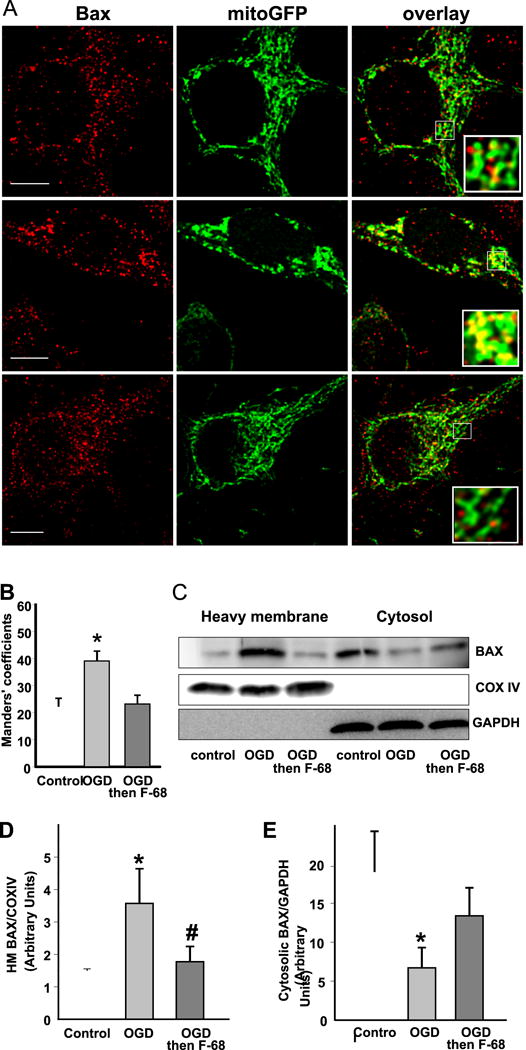

An early step in MOMP induction is the translocation of BAX from cytosol to the OMM. We determined whether F-68 altered this translocation. We used cultured rat embryonic hippocampal neurons expressing adenovirus-transduced, mitochondrially targeted eGFP (mito-GFP). These neurons were subjected to OGD or not, and treated with F-68 or not. At 6 hrs after insult, neurons were fluorescently immunostained for BAX using an antibody not specific for BAX activation, and neurons imaged with confocal microscopy. To quantify colocalization on a cell-by-cell basis, unbiased intensity correlation analysis was performed, reported as the Manders coefficient (Manders et al., 1993). In control neurons, mito-GFP exhibited interconnected worm-like structures consistent with healthy mitochondria, and BAX immunoreactivity was primarily cytosolic (Fig. 5A). In contrast, OGD-treated cells exhibited rounded, coalesced mitochondria, and BAX immunoreactivity was similarly coalesced into large puncta, overlapping with mito-GFP (Fig. 5A). In neurons treated with F-68 (30 μm) after OGD, mitochondrial morphology and the distribution of BAX immunoreactivity were indistinguishable from that seen in control neurons (Fig. 5A). Mean Manders co-localization coefficient between BAX and mitochondria was markedly and significantly increased in OGD-treated neurons compared with control (Fig. 5B). However, in F-68 treated neurons, the mean Manders co-localization coefficient was not significantly different from control (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that F-68 both inhibits BAX translocation to mitochondria and preserves, at the light microscopic level, mitochondrial morphology. Similar evidence for F-68-mediated inhibition of BAX translocation was obtained using cytosolic and heavy membrane fractions isolated without detergent from cultured embryonic neurons following exposure to OGD or not, with subsequent treatment with F-68 or not (Fig. 5C). Western blots of BAX immunoreactivity demonstrated OGD markedly increased BAX immunoreactivity in the heavy membrane fraction (Fig. 5D), and significantly decreased BAX immunoreactivity in the cytosol (Fig. 5E), indicating translocation from cytosol to mitochondria. In contrast, in neurons incubated in F-68 for 6 hrs after OGD, mitochondrial BAX immunoreactivity was not significantly decreased compared with OGD alone (Fig. 5D). These two lines of evidence strongly suggest that F-68 prevents MOMP initiation through inhibition of BAX translocation following OGD. However, whether F-68 acts directly on mitochondria, or upstream of BAX activation remained unclear.

Figure 5. F-68 prevents OGD-induced BAX translocation from cytosol to mitochondria.

A. Confocal images of hippocampal neurons expressing mitochondrially targeted GFP (green) and stained for BAX immunoreactivity (red). Scale bar, 10 μm. Note the greater overlap of BAX immunoreactivity with mitochondria after OGD but not OGD followed by F-68. B. Mean Manders coefficients (± SD) between BAX and mito-GFP immunoreactivity, demonstrating increased co-localization of BAX with mitochondria after OGD but not after OGD followed by F-68 (30 μm) C. Representative Western blots of BAX immunoreactivity in heavy membrane and cytosolic fractions of neurons subjected to control or OGD 6 hr previously. Blots were stripped and blotted with the mitochondrial marker COX IV and the cytosolic marker GAPDH to identify fractions and normalize intensities for protein loading. D, E, Quantification of BAX immunoreactivity in heavy membrane (D) and cytosolic (E) fractions. Data are expressed as means (± SD) of ratios of BAX/COX IV or BAX/GAPDH. Copyright The Journal of Neuroscience. Reproduced with permission.

F-68-induced protection from OGD has recently been reported in cortical neurons (Luo et al., 2015), with important methodological differences. First, in that work, OGD was induced a Billups-Rothenberg chamber, in which the aqueous media containing cells gradually equilibrates with the gases flushed through the chamber. This approach results in a gradual decrease in pO2 in the media, in contrast with the acute drop we induced. Second, neurons were incubated in F-68 prior to and during OGD, rather than after OGD. Finally, neuronal survival was measured 10 min after OGD, rather than at 48 hrs after OGD. Nonetheless, F-68 (10-100 μm) reduced acute neuronal death as quantified by LDH release and MTT assay. Notably, Western Blot studies demonstrated that F-68 decreased cytochrome c release into the cytosol and inhibited caspase-3 activation. The survival data in the Luo (2015) study were derived from measures more commonly used to measure necrotic death. In addition, the data presented do not address the extent to which the OGD paradigm employed induced caspase-dependent death. Nonetheless, the F-68-induced protection of neurons from OGD suggests that F-68 may act through mechanisms similar to those we have reported.

3. Interaction of F-68 with mitochondria and in vivo efficacy

3.1 Introduction

From the above, current understanding of the mechanisms by which hydrophilic Pluronics rescue neurons from acute substrate deprivation may be summarized: 1) Pluronics interact with phospholipid bilayers, including the plasma membrane and mitochondrial membranes; 2) Pluronic F-68 acts directly on mitochondria after injury, preventing BAX translocation from cytosol to mitochondria and loss of Δψm, blocking release of cytochrome c from the IMM, and preventing activation of caspases. Taken together, these observations suggest that Pluronic F-68 inhibits MOMP through direct interaction with mitochondria. To test this hypothesis, we performed in vitro experiments to study F-68 actions on MOMP directly, and to visualize localization of F-68 in injured neurons. For these studies, we purified the F-68 obtained from BASF to remove the approximately 15% poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide) diblock copolymer, and other, low molecular weight compounds that are present in raw F-68.

Finally, to understand whether our in vitro observations of F-68-induced neuronal rescue in vitro, we performed a proof-of-principle study to understand whether F-68 could rescue neurons following hypoxia-ischemia in vivo. Here, we employed the Mongolian gerbil model of global forebrain ischemia, after which animals were administered continuous infusions of F-68 or placebo into the cerebral ventricle, and their anatomic and behavioral outcomes assessed three weeks after injury.

3.2 Methods

3.2.1 Materials

Pluronic F-68 was obtained from BASF. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were obtained from ATCC. Cell culture media and supplements, anti-cytochrome oxidase subunit IV (RRID: AB_2535839), and fluorescence-tagged secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen. Anti-TOM20 (RRID: AB_628381) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-malate dehydrogenase 2 (RRID: AB_2535880 was from Fisher Scientific. Antio-GRP78/BiP (RRID: AB_2571635) was from Abcam. All other chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

3.2.2 Purification of raw F-68

Raw Pluronic F-68 was purified of residual poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide) diblock copolymer and other, low molecular weight compounds by dialysis against dichloromethane, methanol, and finally water in a 10 kDa membrane. The resulting polydispersity index was < 1.2.

3.2.3 Isolation and purification of rat brain mitochondria

Brain mitochondria were isolated in mannitol-sucrose medium and purified on a discontinuous Percoll gradient according to standard procedures performed at 4° C in the presence of a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sims and Anderson, 2008). The cerebral cortices from a male Sprague-Dawley rat (250g) were briefly homogenized in isolation buffer containing 225 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, free fatty acid-free), 1 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and cleared by centrifugation at 1,300 × g for 3 min. The cleared homogenate was mechanically disrupted with nitrogen cavitation at 500 psi for 30 minutes, centrifuged at 30,700 × g in 24% Percoll, and the resulting pellet layered onto a discontinuous Percoll gradient of 15%, 25%, and 40%. The fraction containing mitochondria was washed in isolation buffer by centrifugation at 16,700 × g twice to produce a loose pellet. This pellet was washed and pelleted twice more by centrifugation at 7,000 × g in isolation buffer, then re-suspended, and an aliquot taken for assay of protein concentration. Mitochondria were suspended in fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (0.5%) at a final concentration of 20 μg/μl. Western blots of proteins localized to the mitochondria (Tom20, COX4), cytosol (GAPDH), and ER (GRP78/BiP) were performed on aliquots from the whole brain homogenate and the mitochondrial fraction were compared to determine purity (Fig. 6A).

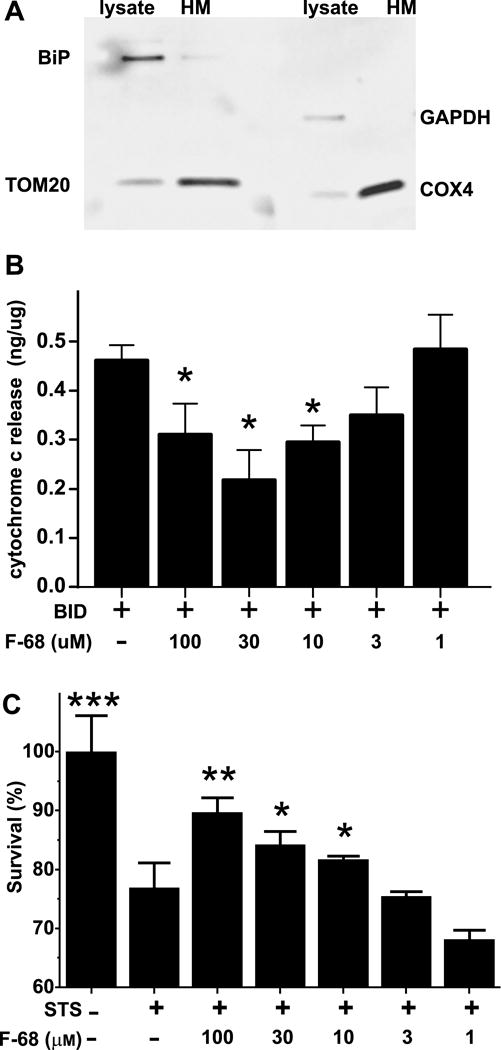

Figure 6. F-68 interacts directly with mitochondria.

A. Representative Western blot of heavy membrane fraction and whole lysate from a rat brain demonstrating that the heavy membrane fraction in enriched in mitochondria. Immunoreactivity for BiP, an ER marker, and GAPDH, a cytosol marker are virtually absent from the heavy membrane fraction, while two mitochondrion-specific markers — TOM20 and COX4 are enriched. B. F-68 inhibits tBID-induced cytochrome c release in a concentration dependent fashion. ***P<0.0001, **P<0.001, *P <0.01 compared with tBID-induced release. C. Staurosporine induced death of wild type mouse embryonic fibroblasts, which occurs through activation of MOMP, is inhibited by F-68 in a dose-dependent fashion. STS: staurosporine. ****P<0.0001 compared with control: **P<0.001, *P <0.01 compared with staurosporine.

3.2.4 tBID induction of MOMP in isolated mitochondria

Mitochondria (30 μg) were incubated for 30 min at 37° C in a buffer containing (in mm) KCl 125, MgCl2 0.5, succinate 3.0, 3.0 glutamate 3.0, HEPES, pH 7.4, fatty acid-free BSA 1 mg/mL, with a cocktail of protease inhibitors and of the caspase inhibitor BocAspFMK (10 μm) and with 1.5 nm recombinant mouse, caspase-8-cleave BID (tBID, R&D Systems. Minneapolis, MN). Samples were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min at 4° C and the supernatant frozen at −80° C.

3.2.5 Measurement of cytochrome c release

A solid phase ELISA kit for detection of rodent cytochrome c (Quantikine, R&D Systems) was used to measure cytochrome c release in duplicate from isolated CNS mitochondria (30 μg protein/sample) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We used alamethicin to permeabilize the membrane to determine maximal cytochrome c release (Brustovetsky et al., 2002; Brustovetsky et al., 2003). F-68 effects were calculated as the percentage of tBID-induced cytochrome c release above spontaneous release.

Induction of MOMP in MEFs and measurement of MEF survival

Equal numbers of MEFs were plated in white 96-well plates and allowed to proliferate for 24 hrs. Following 24 hrs of incubation in staurosporine in the presence of varying concentrations of F-68, a luminometric assay of total ATP was performed (CellTiter-Glo, Promega, Madison, WI) in triplicate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence counts were normalized to those of untreated wells and expressed as a percent.

3.2.6 Synthesis of fluorescently-labeled α-amino-ω-BODIPY-Pluronic F-68 (BODIPY-F-68-NH2)

Synthesis of this fluorescent, paraformaldehyde-fixable Pluronic derivative was achieved by first synthesizing α,ω-bis(amino)-Pluronic F-68, followed by conjugating BODIPY FL-C5 NHS ester in a low molar ratio to produce a degree of dye labeling < 1 dye molecule per co-polymer molecule. Synthesis of α,ω-bis(amino)-Pluronic F-68. Pluronic F-68 (5.0 g, 0.60 mmol), anhydrous triethylamine (0.5 mL), and anhydrous dichloromethane (50 mL) were combined. 4-Toluenesulfonyl chloride (692 mg, 3.60 mmol) was added, stirred under N2 for 24 hrs and concentrated by rotary evaporation to afford the Pluronic F-68-bis(tosylate). This compound, combined with sodium azide (844.4 mg, 13.0 mmol), and water (50 mL), was heated to reflux for 45 hrs, allowed to cool to room temperature, then dialyzed against water with a 3.5 kDa membrane and lyophilized, producing α,ω-bis(azido)-Pluronic F-68 as a fluffy white powder in 89% yield. Next, the azide-functionalized Pluronic F-68 (4.1 g, 0.50 mmol) and triphenylphosphine were dissolved in THF (50 mL) and stirred at room temperature under N2 for 30 min. Water (5 mL) was added and the solution stirred at room temperature under N2 for 18 hrs. The mixture was concentrated by rotary evaporation, and the crude polymer residue purified by dialysis against dichloromethane, methanol, and finally water in a 10 kDa membrane. The aqueous polymer solution was filtered and lyophilized to give α,ω-bis(amino)-Pluronic F-68 as a fluffy white solid in a 33% yield. Synthesis of fluorescently-labeled α-amino-ω-BODIPY-Pluronic F-68. α,ω-Bis(amino)-Pluronic F-68 (134 mg, 0.016 mmol) was dissolved in pH 9 0.2 M sodium bicarbonate buffer (13 mL). A solution of BODIPY® FL-C5 NHS ester (5.0 mg, 0.013 mmol) in DMSO (0.5 mL) was added to the vial and the resulting solution stirred at room temperature under N2 protected from light. After 18 hours, the polymer-dye conjugate was dialyzed extensively against water in a 3.5 kDa membrane. The conjugate solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate membrane and α-amino-ω-BODIPY-Pluronic F-68 was isolated by lyophilization in 82% yield. Absorption at 504 nm confirmed BODIPY conjugation, and the molar ratio of BODIPY to Pluronic was estimated to be 0.105, verifying the heterobifunctionality of the α-amino-ω-BODIPY-Pluronic F-68 sample.

3.2.7 Cultured embryonic hippocampal neurons

Hippocampal neurons from embryonic day 18 Sprague-Dawley rats were isolated, cultured on glass coverslips and maintained in Neurobasal medium with B27 supplement as previously reported (Plant et al., 2011; Shelat et al., 2013; Suresh et al., 2016).

Oxygen-glucose deprivation

Oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) was induced in cultured neurons as previously reported (Shelat et al., 2013). Briefly, the O2 and CO2 tensions of glucose-free, bicarbonate-buffered saline was equilibrated overnight in a humidified chamber containing a 37° C humidified atmosphere containing 1% oxygen and 5% CO2. Cultured neurons at 10–15 days in vitro were incubated in equilibrated buffer for 45 minutes. Placebo-treated neurons were incubated in an otherwise identical, glucose-containing buffer in a standard CO2 containing incubator at 37 ° for 45 minutes. Following incubation, coverslips were placed back in their original media in the incubator containing BODIPY FL-F-68 — NH2 (30 μm).

3.2.8 Immunohistochemistry

Neurons were processed for immunohistochemistry as previously reported (Plant et al., 2016; Plant et al., 2012; Shelat et al., 2013). Paraformaldehyde-fixed neurons were permeabilized with Triton X-100 (0.2%), and non-specific binding antibody binding blocked with serum of the species in which the secondary antibodies were raised. Neurons were incubated with anti-Tom20 to demarcate the OMM and anti-MDH2 to identify the mitochondrial matrix. MDH2 immunoreactivity was detected with Alexa 568-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG1-specific antibody and Tom20 detected with Alexa 647-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG2a-specific antibody. Preliminary studies demonstrated no cross-reactivity between subclass-specific IgGs.

3.2.9 Super-resolution imaging and analysis

Coverslips containing neurons were mounted in mercaptoethylamine (100 mM) and imaged at 30 Hz on the stage of a Leica SR GSD 3D microscope using a 160× 1.43 N.A. objective and a Prime 95B CMOS camera (Roper Scientific). The fluorophores in the preparation (Alexa Fluor 647, Alexa Fluor 568, and BODIPY FL) were sequentially excited using ground state depletion microscopy with 642 nm, 532 nm, and 488 nm lasers, respectively, to generate fluorescent events from single fluorophore molecules. Events were localized using the thunderSTORM plugin (Ovesny et al., 2014) within the FIJI distribution of ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012) to produce reconstructed image stacks of 800 micron thick volumes in 20, 50 μm-thick slices. XY resolution for this super-resolution imaging was mapped at 20 nm. Image stacks were reconstructed in three dimensions with Imaris (Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland).

3.2.10 Induction of global brain ischemia

Global forebrain ischemia of male Mongolian gerbils (M. unguiculatus, 70–80g) was performed as previously reported (Seal et al., 2006) using bilateral carotid artery occlusion under isoflurane anesthesia (4% induction, 0.5–1% maintenance) and constant striatal temperature control (36° C), with the addition of transient systemic hypotension. Mean arterial blood pressure was continuously monitored via a femoral artery catheter. Blood (1–2 ml) was slowly withdrawn to reduce mean blood pressure to less than 50% of mean baseline pressure. Next, both carotid arteries were occluded with vascular clamps for 3 min. Immediately after restoration of bilateral carotid blood flow was confirmed, the withdrawn blood was slowly infused into the femoral artery and blood pressure monitoring continued. Control animals were subjected to a sham operation in which the same surgical procedures were performed without blood withdrawal or carotid occlusion.

3.2.11 Intra-cerebroventricular administration of F-68/placebo

Following completion of forebrain ischemia or sham operation and under continuing brain temperature control, a brain infusion cannula was stereotaxically placed into the left lateral cerebral ventricle through a small burr hole in the skull and connected to an osmotic pump containing either artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF (in mm): Na 154, KCl 3.0, Ca 1.4, Mg 0.9, Cl 136, PO4 1.0) or F-68 (10 mM in aCSF). The pump was subsequently placed under the skin at the back of the neck. The osmotic pump delivered its contents at 1 μl/hr for seven days. To prevent post-operative hypothermia, animals spent the first post-operative three hours in an isolette maintained at 35° C. The surgeon was unaware of the contents of the osmotic pump. After the seven day drug administration period, animals were maintained for a further 14 or 21 days, for histological or behavioral assessment, respectively.

3.2.12 Determination of hippocampal CA1 death

Neuronal death in the CA1 region was quantified as previously reported (Seal et al., 2006) by two counters unaware of the treatment conditions of the animal. Differences between groups were analyzed with ANOVA, and post-hoc differences tested and corrected for multiple comparisons with Bonferroni.

3.2.13 Measurement of Spatial Learning and Memory

To measure hippocampus-dependent spatial learning and memory, the Morris water maze, which requires animals to use spatial cues to swim to a hidden platform (Morris, 1984) was used. After 1 day of acclimatization to the environment, and one day training with a visible platform, animals received two blocks of four trials with the hidden platform daily for two days. The swimming path of each gerbil was monitored by an overhead video camera connected to a personal computer running a tracking system computer program (Anymaze, Stoelting, Wood dale, IL). A trial was terminated when the gerbil climbed onto the platform or had been swimming for 60 s. Each animal’s swimming distances were averaged per training session, and the mean distances of the treatment cohort averaged and plotted as a function of training session. On the fifth day, gerbils underwent a 60 s-duration probe trial, in which the hidden platform was removed, and the time the animals spent in the quadrant of the pool in which the platform had been located was measured.

3.2.14 Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 6.07 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Differences between groups were analyzed by ANOVA followed by the Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test.

3.3 Results

3.3.1 F-68 interacts directly with mitochondria

We performed three new sets of experiments to understand F-68 interaction with mitochondria and the induction of MOMP. To examine MOMP induction directly, we employed isolated rat cortical mitochondria (Fig. 6A) and induced MOMP by incubating mitochondria in caspase-8 cleaved BID (t-BID), quantifying its extent by measuring cytochrome c release (Kuwana et al., 2002; Llambi et al., 2011). Mean baseline cytochrome c release in the absence of tBID or F-68 was 0.65 ± 0.12 (SEM) ng/μg mitochondrial protein, and this spontaneous release was not significantly different from release in the presence of F-68 (30 μm, 0.59 ± 0.03 ng/μg protein). In response to tBID (30 nm) cytochrome c release significantly increased over spontaneous release (0.46 ng/μg protein). In the presence of F-68, tBID-induced cytochrome c release significantly decreased in a dose-dependent fashion (N=3, F(4, 10)= 10.51, p=0.001). At < 10 μm, F-68 had no effect on cytochrome c release. However, in the presence of increasing F-68 concentrations, cytochrome c release significantly and progressively decreased (Fig. 6B). Similar to our neuronal rescue studies, 100 μm F-68 was less effective than 30 μm. Because tBID acts directly on mitochondria to induce MOMP, these data indicate that F-68 acts at the mitochondrion to inhibit MOMP.

We next wished to induce MOMP in intact cells without the complex ionic (Luo et al., 2008; Medvedeva et al., 2009; Stanika et al., 2009), oxidative (Fukui and Zhu, 2010; Niatsetskaya et al., 2012), signal transduction (Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2011), and metabolic (Connolly et al., 2014; Pivovarova and Andrews, 2010) cascades of intracellular events that accompany substrate deprivation in neurons, including OGD. Accordingly, as a cellular model of MOMP, we used the stereotypical response of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) to staurosporine, a broad range kinase inhibitor that, in the absence of Bcl-2 overexpression, induces cytochrome c release (Hamacher-Brady and Brady, 2015; Rehm et al., 2009) and caspase-9-dependent apoptosis (Manns et al., 2011). MEFs grown in 96-well plates were exposed to staurosporine (30 nm) or not in the presence and absence of a range of F-68 concentrations for 24 hrs, and survival measured. Staurosporine exposure killed 25% of cells present in control wells at 24 hrs. Co-incubation of cells with F-68 significantly decreased cell death in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 6C), at the minimal effective concentration of 10 μm. Unlike our studies in isolated mitochondria, 100 μm was not less effective than 30 μm. The data from this model system of MOMP-induced death suggests that F-68 decreased staurosporine-induced MOMP.

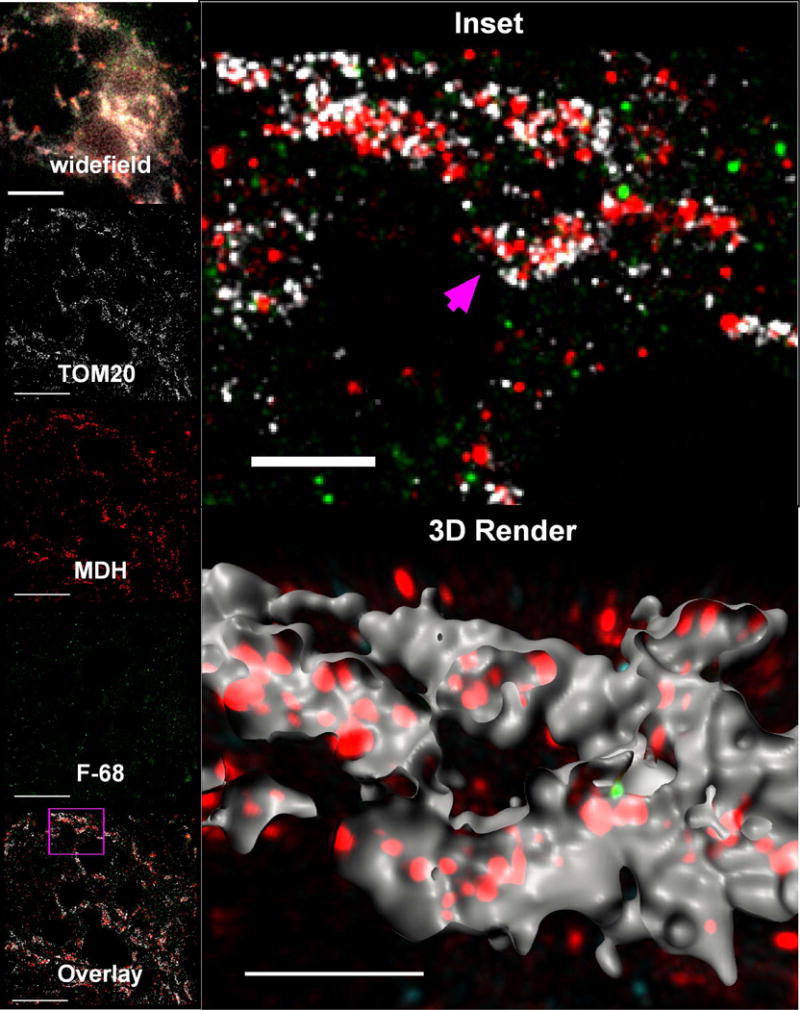

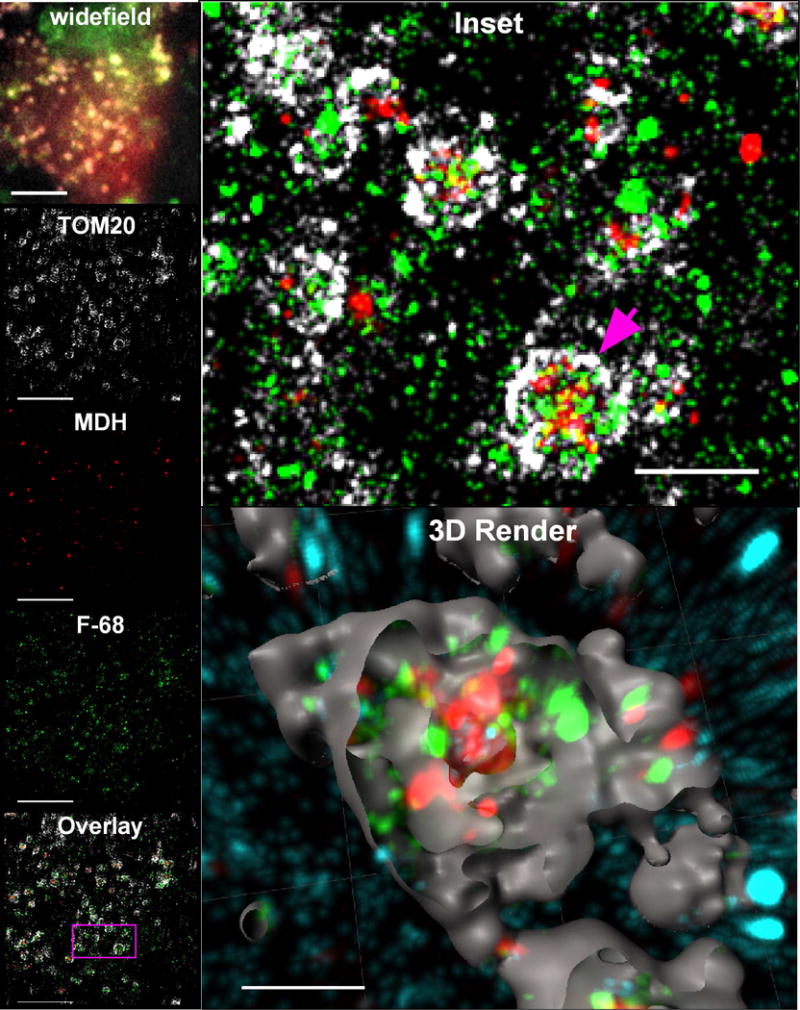

The above results predict that, in order to inhibit MOMP and maintain Δψm following OGD, F-68 interacts with mitochondria. Accordingly, we employed super-resolution microscopy to image F-68 localization in neurons by synthesizing a fixable, fluorescent derivative of F-68 (BODIPY-F-68-NH2). Cultured embryonic hippocampal neurons were exposed to OGD or control buffer for 45 minutes, and then incubated in BODIPY-F-68-NH2 for 2 hours. Neurons were then fixed and double immuno-stained for TOM20, a marker of the OMM (detected with Alexa Fluor 647), and malonate dehydrogenase (MDH), present in the mitochondrial matrix (detected with Alexa Fluor 568). BODIPY FL and these fluorophores were chosen because we found that each photo-switches stochastically under appropriate illumination, providing sub-diffraction imaging (Bretschneider et al., 2007). Neurons were imaged with Ground State Depletion microscopy and fluorescent events mapped with Stochastic Optical Reconstruction to near 20 nm localization in XY planes, and <200 nm in the Z plane. For each fluorophore, between 500,000 and 750,000 fluorescent events were collected over 40,000–60,000 frames.

In both control and OGD-exposed neurons, immunoreactivity of the OMM at super resolution was punctate rather than continuous. We could not find staining conditions that would produce continuous fluorescent structures. Three-color super-resolution imaging clearly distinguished OMM from mitochondrial matrix. In control neurons, TOM20 punctate immunoreactivity outlined elongated structures with closely apposed MDH immunoreactive puncta (Fig. 7, inset). Three dimensional rendering demonstrated long, interconnected tubular TOM20 structures containing MDH (Fig. 7, 3D render). In OGD-exposed neurons, however, TOM20 immunoreactive puncta enclosed small, disconnected circular structures enclosing MDH immunoreactive puncta (Fig. 8, inset). In both conditions, these structures and relationships are consistent with the OMM enclosing the mitochondrial matrix, and with the classically described fragmented and rounded mitochondrial morphology following OGD.

Figure 7. F-68 does not localize to mitochondria of healthy neurons.

Photomontage of triple-label, super-resolution imaging of BODIPY FL-tagged F-68 and fluorescent immunoreactivity of the mitochondrial outer membrane protein TOM20 and the mitochondrial matrix protein, malonate dehydrogenase (MDH) in control cultured hippocampal neurons. In these healthy neurons, there is virtually no F-68 fluorescence. In all images, F-68 fluorescence is colored green, MDH immunoreactivity is colored red, and TOM20 immunoreactivity is colored white. widefield: Wide field image (180 × 180 pixels) of the region of interest. Bar: 10 μm. Panels labeled TOM20, MDH, F-68: 2D map of single molecule fluorescence localizations of TOM20 immunoreactivity, MDH immunoreactivity, and BODIPY FL-labeled F-68, respectively, created by the thunderSTORM Plug-in in Fiji. Each panel depicts the same 50 nm thick mapped slice of the total 800 nm thick volume imaged, matching the field shown in widefield. Bars: 5 μm. Inset: Enlarged region delineated by the pink square in the Overlay image. The pink arrow points to the mitochondria rendered in the 3D render, below. 3D Render: Three-dimensional reconstruction of the single fluorescence events in all three channels within the 800 nm thick volume imaged in super-resolution. TOM20 fluorescence has been rendered as surfaces to show mitochondrial volumes, and the surfaces have been cut to show the fluorescence events localized within the mitochondrial volumes. F-68 fluorescence events in contact inside the mitochondrial surfaces are colored green. F-68 fluorescence events outside of the mitochondrial surfaces are colored cyan. Bar: 2 μm. A total of 10 fields of neurons across six independent experiments were imaged.

Figure 8. F-68 localizes to mitochondria of neurons subjected to OGD.

Photomontage of triple-label, super-resolution imaging of BODIPY FL-tagged F-68 and fluorescent immunoreactivity of TOM20 and MDH in cultured hippocampal neurons exposed to 45 min OGD. Note the presence of multiple F-68 molecules within the mitochondrion, as well as fewer molecules in the extra-mitochondrial space. In all images, fluorophores are pseudocolored as described in Fig. 8. widefield: Wide field image (180 × 180 pixels) of the region of interest. Bar: 10 μm. Panels labeled TOM20, MDH, F-68: 2D map of single molecule fluorescence localizations of TOM20 immunoreactivity, MDH immunoreactivity, and BODIPY FL-labeled F-68, respectively, created thunderSTORM Each panel depicts the same 50 nm thick optical slice of the total 800 nm thick volume imaged, matching the field shown in widefield. Bars: 5 μm. Inset: Enlarged region delineated by the pink square in the Overlay image. The pink arrow points to the mitochondrion rendered in the 3D render, below. 3D Render: Three-dimensional reconstruction of the single fluorescence events in all three channels within the 800 nm thick volume imaged in super-resolution. TOM20 fluorescence has been rendered as surfaces to show mitochondrial volumes, and the surfaces have been cut to show the fluorescence events localized within the mitochondrial volumes. F-68 fluorescence events in contact inside the mitochondrial surfaces are colored green. F-68 fluorescence events outside of the mitochondrial surfaces are colored cyan. Bar: 2 μm. A total of 17 fields of neurons across six independent experiments were imaged.

In control neurons, we observed few, if any F-68 molecules (Fig. 7, 3D render). In contrast, F-68 molecules were highly abundant in association with OGD-exposed neurons. Here, F-68 molecules primarily localized to mitochondria, in close association with the OMM, as delineated by TOM20 staining (Fig. 8, inset, 3D render, green). In contrast, few F-68 molecules within mitochondria were noted to co-localize with MDH (matrix) immunoreactivity. Finally, some F-68 puncta were not localized to mitochondria (Fig. 8, 3D render, cyan). These extra-mitochondrial puncta were, in general, smaller than the TOM20-associated F-68 puncta.

This dataset (5 biological replicates, 10 images per replicate group on 2 coverslips each) suggest that F-68 localizes to neuronal mitochondrial following injury but not in the absence of injury. Three dimensional rendering suggests that this association is primarily within the OMM. This data provide imaging support for our physiological evidence suggesting that F-68 interacts with mitochondria to inhibit MOMP.

3.3.2 F-68 rescues hippocampal neurons from global brain ischemia in vivo

Having found that F-68 rescues neurons following OGD in vitro, we performed a pilot study to determine whether F-68 rescues neurons following transient HI in the Mongolian gerbil. This species has been frequently reported to have no posterior cerebral communicating arteries (PCAs, Levine and Sohn, 1969), and transient occlusion of both carotid arteries (2VO) has been employed to induce global forebrain ischemia (for example: Kirino, 1982; Koo Hwang et al., 2006; Kowalczyk et al., 2009). However, we previously determined that Mongolian gerbils vary widely in the presence and caliber of PCAs, and that this variation determines the extent and laterality of injury following 2VO (Seal et al., 2006). Accordingly, we induced consistent forebrain ischemia in this species using 2VO plus induced systemic hypotension (2VO-H), an approach used previously in mice and rats that results in severe bilateral injury to the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Hartman et al., 2005; von Euler et al., 2006; Wellons et al., 2000). Control animals were subjected to a sham operation in which the same surgical procedures were performed without the induction of 2VO-H. To bypass the blood-brain-barrier, we administered F-68 (10 mm in aCSF) or aCSF alone into the lateral cerebral ventricle using an osmotic pump to provide continuous drug infusion for seven days. Animals were not evaluated for another 21–28 days after F-68/placebo treatment was completed, in order to ensure that HI-induced neuronal death would be complete (Sugawara et al., 2002).

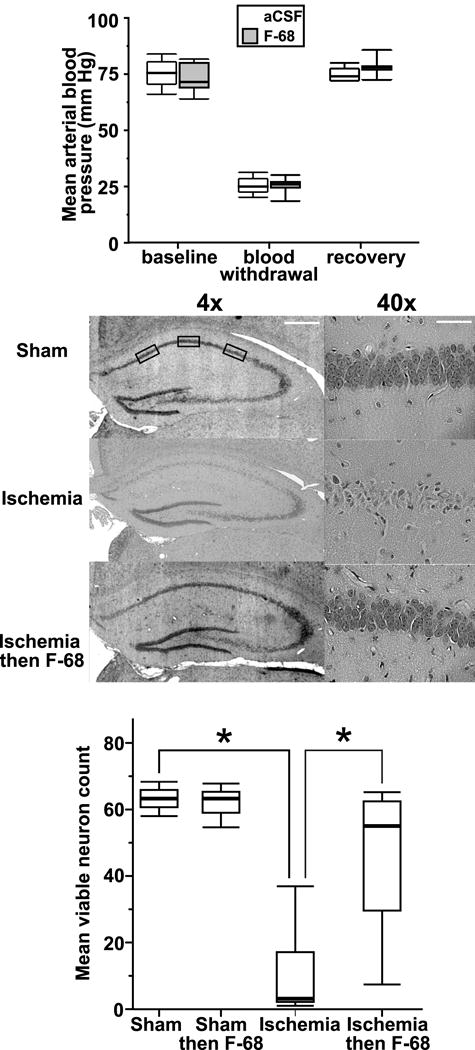

Mean blood pressures during induction of ischemia were no different between sham and ischemic animals (Fig. 9A). F-68 treatment did not alter the mean number of viable CA1 neurons seen in sham operated animals. However, 2VO-H followed by infusion of aCSF alone for seven days, resulted in almost complete killing of CA1 neurons at 21 days post ischemia (Figs. 9B, 9C). Notably, in animals subjected to 2VO-H then treated with F-68, the mean number of viable CA1 neurons 21 days post ischemia was significantly increased compared with ischemia plus aCSF (p<0.001), with the mean number approaching sham (Figs. 9B, 9C).

Figure 9. Continuous ICV administration of F-68 for 7 days following global forebrain ischemia rescues hippocampal CA1 neurons in the Mongolian gerbil.

Top: Mean arterial pressures in Mongolian gerbils before and after blood withdrawal to induce hypotension prior to bilateral carotid occlusion, and after infusion of removed blood following restoration of carotid artery blood flow. Box and whisker plots: the upper and lower borders of the box denote the 75h and 25th percentiles of each group, respectively, and the line inside the box denotes the median. The upper and lower whiskers show the 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively. There is no significant difference between the F-68 and placebo groups in mean blood pressures. Middle: Representative H&E stained 8 μm thick brain sections from each group at two different magnifications. Boxes denote the anatomically defined regions in which viable neurons were counted according to published criteria. Bar: 4x: 0.5 mm; 40x: 50 μm. Bottom: Box and whisker plots of numbers of viable neuron within the CA1 region sham-operated animals and animals subjected to 2VO-H who then received continuous ICV administration. (Sham/placebo n= 12; sham/F-68 n= 10; 2VO-H/placebo: n= 19; 2VO-H/F-68 n= 23).*P<0.001 compared with Ischemia.

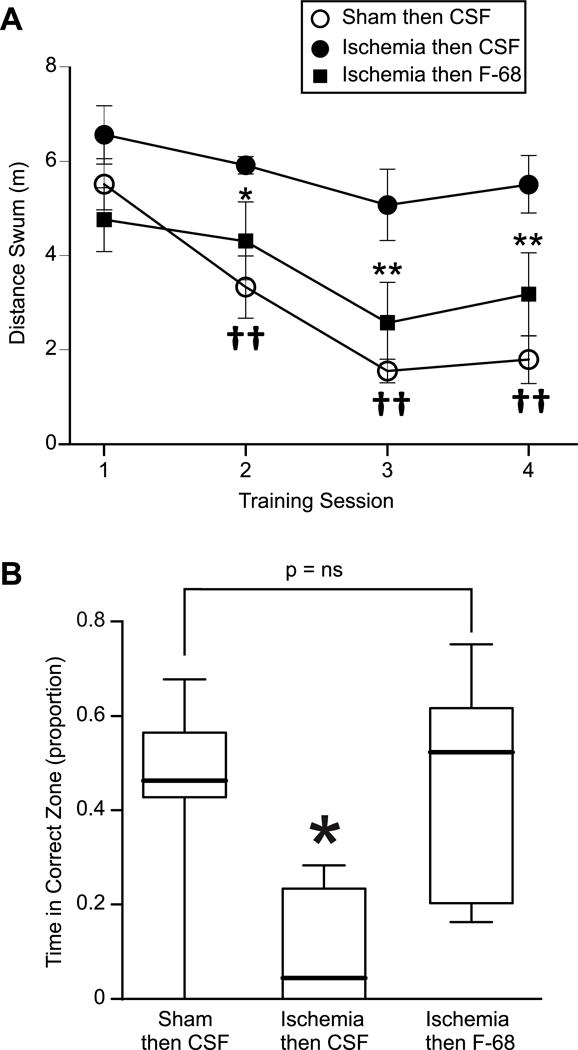

Having found that F-68 rescued hippocampal CA1 neurons from death following global forebrain HI, we asked whether this rescue was reflected in a reduction of HI-induced, hippocampus-dependent functional deficits. Accordingly, we induced global forebrain ischemia or sham in a separate cohort of animals, administered F-68 or placebo to animals subjected to HI. Two weeks following HI or sham, we measured hippocampus-dependent spatial learning and memory, using the Morris water Maze (Morris, 1984). To measure learning in a physical deficit-independent manner, we determined total distance swum during a trial.

The mean distances swum to the hidden platform were not significantly different between the groups during the first training session, indicating that the 2VO-H animals did not exhibit motor impairment (Fig. 10A). As anticipated, animals subjected to sham operation/placebo infusion, demonstrated spatial learning, swimming progressively shorter distances to reach the platform over course of the training sessions (Fig. 10A). In contrast, animals subjected to 2VO-H/placebo infusion did not significantly decrease the distance swum over the training period (Fig. 10A), suggesting that, as anticipated, 2VO-H significantly impaired spatial learning. In sharp contrast, in animals subjected to 2VO-H/F-68 infusion, the mean distance swum decreased progressively over the training sessions, demonstrating learning. Distances swum to the hidden platform on sessions 3 and 4 by the 2VO-H/F-68 group were significantly shorter compared with 2VO-H/placebo animals, but not significantly different from that of sham/placebo animals (Fig. 10). These data suggest that F-68 decreased the 2VO-H-induced loss of spatial learning. The results of the probe trial are shown in Fig. 10B. The median time spent in the correct quadrant by the 2VO-H animals was significantly smaller than that of the sham/placebo animals, indicating that 2VO-H decreased spatial memory. In contrast, the median time spent in the correct quadrant by the 2VO-H/F-68 animals was significantly greater than that of the 2VO-H group, and not different from the sham/placebo group. Taken together, the anatomical and functional results of this pilot in vivo study suggest that F-68, when administered directly into the cerebral ventricle for seven days, rescues hippocampal neurons from global forebrain ischemia and reduces the loss of hippocampus-dependent function that follows global forebrain ischemia.

Figure 10. F-68 administration following global brain ischemia improves hippocampus-dependent spatial learning and memory.

A. Morris water maze learning curves of Mongolian gerbils 14 days after sham operation/placebo, 2VO-H/placebo, or 2VO-H/F-68 ICV administration for 7 days. Plotted are mean distances swum (± SEM) to find the hidden platform as a function of training session. Two way ANOVA with repeated measures: F-68/Placebo F(2,71) 16.94, P<0.0001; Training session: F(2,213) 10.34 P<0.0001; Drug × training session interaction: F(6,213) 2.246 P= 0.04. Post hoc comparisons (Holm-Sidak) *P<0.05, **P<0.01, 2VO-H/placebo vs 2VO-H/F-68; ††P< 0.0001 2VO-H/placebo vs sham/placebo. B. Probe trial performance among the groups. Box and whisker plots denote percentiles as in Fig. 9. *P<0.05.

4. Discussion

In its interactions with membranes, F-68 and other hydrophilic Pluronics constitute a novel approach to rescuing neurons from acute substrate deprivation. Initially believed to seal the plasma membrane following loss of membrane integrity, increasing numbers of studies in model membrane systems strongly suggest that hydrophilic Pluronics appose to membranes, rather than inserting into them (Cheng et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012). In fact, insertion of hydrophobic Pluronics into membranes disrupts membranes in some systems, resulting in cell injury. Recently, F-68-induced rescue of neurons from substrate deprivation through blockade of mitochondrial apoptosis have delineated alternate mechanisms by which Pluronics rescue neurons. Our recent data showing that F-68 reduces tBID-induced MOMP in isolated mitochondria indicates that F-68 is active at mitochondrial membranes. In addition, the rescue by F-68 of mouse embryonic fibroblasts from staurosporine-induced MOMP provides additional evidence that F-68 acts at mitochondria of mammalian cells in general, rather than in a neuron-specific injury pathway. Finally, super-resolution imaging confirms that F-68 is present at and within the mitochondrial outer membrane of neurons after acute injury.

Since the initial observations that, after ischemia, BAX is upregulated in central neurons (Krajewski et al., 1995), and translocates to neuronal mitochondria (Cao et al., 2001), BAX has been observed to play a key role in multiple models of ischemia-induced neuronal death (Fan et al., 2012; Lai et al., 2014; Pei et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2011). In addition to BAX, BID has been implicated in neuronal death following OGD in vitro and HI in vivo (Plesnila et al., 2001), as well as in early cytochrome c release following HI (Yin et al., 2002). Accordingly, our findings that F-68 blocks BAX translocation following OGD and reduces tBID-induced cytochrome c release in isolated mitochondria suggest that F-68 may abort MOMP through interactions with one or both proteins.

Activation of BAX by tBID requires interactions among tBID, BAX and mitochondrial cardiolipin (Kuwana et al., 2002; Lutter et al., 2000; Martinou and Youle, 2011; Raemy and Martinou, 2014), although the mitochondrial carrier homolog MCTH2/MIMP can replace cardiolipin as a tBID receptor (Raemy et al., 2016; Zaltsman et al., 2010). Accordingly, F-68 induced inhibition of tBID binding to mitochondria and subsequent reduced recruitment of BAX to the OMM could underlie the action of F-68 following injury. Cardiolipin is a highly negatively charged phospholipid localized primarily to the inner mitochondrial membrane. tBID binds cardiolipin at the OMM through its central alpha helices (Petit et al., 2009), likely at sites of contact between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes (Martinou and Youle, 2011). Whether F-68, a nonionic molecule preferentially adsorbs to cardiolipin or cardiolipin-contain structures is not known, although it is an attractive hypothesis for a phospholipid-active Pluronic. Determining whether and by what means F-68 may prevent translocation of tBID to mitochondria, or perhaps block its activity, will improve understanding of its role in rescuing neurons from injury.

Caspase-dependent intrinsic apoptosis may play a smaller role in ischemic neuronal death than previously believed, yet BAX plays roles in other death pathways following neuronal ischemia. For example, BAX deficiency also reduces TUNEL-negative death in vitro and in vivo and reduces Δψm dissipation, possibly by regulating Ca++ homeostasis at the ER (D’Orsi et al., 2015). Nonetheless, injury to mitochondria remains an irreversible final common pathway to neuronal death following ischemia, suggesting that F-68 effects on mitochondria may provide an effective neuronal rescue strategy. Our proof-of-principle study of the efficacy of F-68 infusion following global HI in vivo raises the possibility that F-68, or similar molecules, may have a relevant role in reducing neuronal injury.

Highlights.

Hydrophilic Pluronic triblock copolymers rescue neurons from death following substrate deprivation

Pluronic F-68 inhibits intrinsic apoptosis following oxygen-glucose deprivation

F-68 acts directly on mitochondria to prevent mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization

Super-resolution microscopy shows that F-68 localizes within mitochondria of injured neurons

F-68 delivered into the CSF after brain ischemia reduces hippocampal injury and improves function

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Katherine Libesny for technical assistance. Super-resolution imaging was performed at the University of Chicago Integrated Light Microscopy Facility. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 NS056313, which had no role in the design of the studies, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of this report, or the decision to submit this report for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Chemical compounds studied in this article

Poloxamer 188 (Pluronic F-68) (PubChem CID: 10129990 (PEG-PPG-PEG))

Abbreviations: F-68: Pluronic F-68; GUV: giant unilamellar vesicle; POPC: 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; POPG: 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-(phosphor-rac-(1-glycerol)); Biotin-PE: 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanol-amine-N-(cap biotinyl); DHPE: 1,2-dihexa-decanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine; CMC: critical micellar concentration; OGD: Oxygen-glucose deprivation; Δψm: mitochondrial membrane potential; MOMP: outer mitochondrial membrane permeabilization; OMM: outer mitochondrial membrane; MTT: thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; MEFs: mouse embryonic fibroblasts; MDH: malonate dehydrogenase; 2VO: two vessel occlusion; STORM: Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy; PCAs: posterior cerebral communicating arteries; 2VO-H: two vessel occlusion with induced systemic hypotension; aCSF: artificial cerebrospinal fluid. ICV: intra-cerebroventricular.

References

- Albers GW, Goldstein LB, Hess DC, Wechsler LR, Furie KL, Gorelick PB, Hurn P, Liebeskind DS, Nogueira RG, Saver JL. Stroke Treatment Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) Recommendations for Maximizing the Use of Intravenous Thrombolytics and Expanding Treatment Options With Intra-arterial and Neuroprotective Therapies. Stroke. 2011;42:2645–2650. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.618850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandridis P, Hatton T. Poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide)-poly (ethylene oxide) block copolymer surfactants in aqueous solutions and at interfaces: thermodynamics, structure, dynamics, and modeling. Colloid Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 1994;96:1. [Google Scholar]

- Ankarcrona M, Dypbukt JM, Bonfoco E, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S, Lipton SA, Nicotera P. Glutamate-induced neuronal death: a succession of necrosis or apoptosis depending on mitochondrial function. Neuron. 1995;15:961–973. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine GJ, Neher E. Calcium requirements for secretion in bovine chromaffin cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;450:247–271. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfoco E, Krainc D, Ankarcrona M, Nicotera P, Lipton SA. Apoptosis and necrosis: two distinct events induced, respectively, by mild and intense insults with N-methyl-D-aspartate or nitric oxide/superoxide in cortical cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7162–7166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretschneider S, Eggeling C, Hell SW. Breaking the Diffraction Barrier in Fluorescence Microscopy by Optical Shelving. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98:218103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.218103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks C, Wei Q, Feng L, Dong G, Tao Y, Mei L, Xie ZJ, Dong Z. Bak regulates mitochondrial morphology and pathology during apoptosis by interacting with mitofusins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11649–11654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703976104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustovetsky N, Brustovetsky T, Jemmerson R, Dubinsky JM. Calcium-induced cytochrome c release from CNS mitochondria is associated with the permeability transition and rupture of the outer membrane. J Neurochem. 2002;80:207–218. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustovetsky N, Dubinsky JM, Antonsson B, Jemmerson R. Two pathways for tBID-induced cytochrome c release from rat brain mitochondria: BAK- versus BAX-dependence. J Neurochem. 2003;84:196–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G, Minami M, Pei W, Yan C, Chen D, O’Horo C, Graham SH, Chen J. Intracellular Bax translocation after transient cerebral ischemia: implications for a role of the mitochondrial apoptotic signaling pathway in ischemic neuronal death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:321–333. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200104000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CY, Wang JY, Kausik R, Lee KYC, Han S. Nature of Interactions between PEO-PPO-PEO Triblock Copolymers and Lipid Membranes: (II) Role of Hydration Dynamics Revealed by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:2624–2633. doi: 10.1021/bm300848c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly NMC, Düssmann H, Anilkumar U, Huber HJ, Prehn JHM. Single-Cell Imaging of Bioenergetic Responses to Neuronal Excitotoxicity and Oxygen and Glucose Deprivation. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:10192–10205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3127-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Orsi B, Kilbride SM, Chen G, Perez Alvarez S, Bonner HP, Pfeiffer S, Plesnila N, Engel T, Henshall DC, Dussmann H, Prehn JH. Bax regulates neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis. J Neurosci. 2015;35:1706–1722. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2453-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Zhang N, Yin G, Zhang Z, Cheng G, Qian W, Long H, Cai W. Edaravone Protects Cortical Neurons From Apoptosis by Inhibiting the Translocation of BAX and Increasing the Interaction Between 14-3-3 and p-BAD. Int J Neurosci. 2012;122:665–674. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.707714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fannjiang Y, Kim CH, Huganir RL, Zou S, Lindsten T, Thompson CB, Mito T, Traystman RJ, Larsen T, Griffin DE, Mandir AS, Dawson TM, Dike S, Sappington AL, Kerr DA, Jonas EA, Kaczmarek LK, Hardwick JM. BAK alters neuronal excitability and can switch from anti- to pro-death function during postnatal development. Dev Cell. 2003;4:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck JM, Pavlova A, Scott JA, Han S. Quantitative cw Overhauser effect dynamic nuclear polarization for the analysis of local water dynamics. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2013;74:33–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui M, Zhu BT. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase SOD2, but not cytosolic SOD1, plays a critical role in protection against glutamate-induced oxidative stress and cell death in HT22 neuronal cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:821–830. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB, Committee, o.b.o.t.A.H.A.S., Subcommittee, S.S. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2013 Update A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR. The cell’s dilemma, or the story of cell death: an entertainment in three acts. FEBS J. 2016;283:2568–2576. doi: 10.1111/febs.13658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR. Bax/Bak-dependent, Drp1–independent Targeting of X-linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (XIAP) into Inner Mitochondrial Compartments Counteracts Smac/DIABLO-dependent Effector Caspase Activation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:22005–22018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.643064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick JM, Soane L. Multiple functions of BCL-2 family proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman RE, Lee JM, Zipfel GJ, Wozniak DF. Characterizing learning deficits and hippocampal neuron loss following transient global cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2005;1043:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hypothermia after Arrest Study Group. Mild Therapeutic Hypothermia to Improve the Neurologic Outcome after Cardiac Arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:549–556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S, Anwari K, Alsop AE, Yuen WS, Huang DC, Carroll J, Smith NA, Smith BJ, Dewson G, Kluck RM. Identification of an activation site in Bak and mitochondrial Bax triggered by antibodies. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11734. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs SE, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Inder TE, Davis PG. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy, Cochrane Database Syst Rev. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilinc D, Gallo G, Barbee K. Poloxamer 188 reduces axonal beading following mechanical trauma to cultured neurons. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2007;2007:5395–5398. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4353562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilinc D, Gallo G, Barbee KA. Mechanical membrane injury induces axonal beading through localized activation of calpain. Exp Neurol. 2009;219:553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirino T. Delayed neuronal death in the gerbil hippocampus following ischemia. Brain Res. 1982;239:57–69. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90833-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo Hwang I, Yoo KY, Won Kim D, Kang TC, Young Choi S, Kwon YG, Hee Han B, Sung Kim J, Won MH. Na+/Ca2+ exchanger 1 alters in pyramidal cells and expresses in astrocytes of the gerbil hippocampal CA1 region after ischemia. Brain Res. 2006;1086:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk JE, Beręsewicz M, Gajkowska B, Zabłocka B. Association of protein kinase C delta and phospholipid scramblase 3 in hippocampal mitochondria correlates with neuronal vulnerability to brain ischemia. Neurochem Int. 2009;55:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajewski S, Mai JK, Krajewska M, Sikorska M, Mossakowski MJ, Reed JC. Upregulation of bax protein levels in neurons following cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6364–6376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06364.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana T, Mackey MR, Perkins G, Ellisman MH, Latterich M, Schneiter R, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. Bid, Bax, and lipids cooperate to form supramolecular openings in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Cell. 2002;111:331–342. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai XJ, Ye SQ, Zheng L, Li L, Liu QR, Yu SB, Pang Y, Jin S, Li Q, Yu AC, Chen XQ. Selective 14-3-3gamma induction quenches p-beta-catenin Ser37/Bax-enhanced cell death in cerebral cortical neurons during ischemia. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1184. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Canaday DJ, Hammer SM. Transient and stable ionic permeabilization of isolated skeletal muscle cells after electrical shock. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1993;14:528–540. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199309000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, River LP, Pan FS, Ji L, Wollmann RL. Surfactant-induced sealing of electropermeabilized skeletal muscle membranes in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4524–4528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S, Sohn D. Cerebral ischemia in infant and adult gerbils. Relation to incomplete circle of Willis Arch Pathol. 1969;87:315–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llambi F, Moldoveanu T, Tait Stephen WG, Bouchier-Hayes L, Temirov J, McCormick Laura L, Dillon Christopher P, Green Douglas R. A Unified Model of Mammalian BCL-2 Protein Family Interactions at the Mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2011;44:517–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C, Li Q, Gao Y, Shen X, Ma L, Wu Q, Wang Z, Zhang M, Zhao Z, Chen X, Tao L. Poloxamer 188 Attenuates Cerebral Hypoxia/Ischemia Injury in Parallel with Preventing Mitochondrial Membrane Permeabilization and Autophagic Activation. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;56:988–998. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Wang Y, Chen H, Kintner DB, Cramer SW, Gerdts JK, Chen X, Shull GE, Philipson KD, Sun D. A concerted role of Na+ -K+ -Cl- cotransporter and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in ischemic damage. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2008;28:737–746. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Yang X, Zhao S, Wei C, Yin Y, Liu T, Jiang S, Xie J, Wan X, Mao M, Wu J. Hydrogen sulfide prevents OGD/R-induced apoptosis via improving mitochondrial dysfunction and suppressing an ROS-mediated caspase-3 pathway in cortical neurons. Neurochem Int. 2013;63:826–831. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter M, Fang M, Luo X, Nishijima M, Xie X, Wang X. Cardiolipin provides specificity for targeting of tBid to mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:754–761. doi: 10.1038/35036395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YL, Qin P, Li Y, Shen L, Wang SQ, Dong HL, Hou WG, Xiong LZ. The effects of different doses of estradiol (E2) on cerebral ischemia in an in vitro model of oxygen and glucose deprivation and reperfusion and in a rat model of middle carotid artery occlusion. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manders EMM, Verbeek FJ, Aten JA. Measurement of co-localization of objects in dual-colour confocal images. J Microsc. 1993;169:375–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1993.tb03313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns J, Daubrawa M, Driessen S, Paasch F, Hoffmann N, Loffler A, Lauber K, Dieterle A, Alers S, Iftner T, Schulze-Osthoff K, Stork B, Wesselborg S. Triggering of a novel intrinsic apoptosis pathway by the kinase inhibitor staurosporine: activation of caspase-9 in the absence of Apaf-1. FASEB J. 2011;25:3250–3261. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-177527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks JD, Pan CY, Bushell T, Cromie C, Lee RC. Amphiphilic, tri-block copolymers provide potent, membrane-targeted neuroprotection. FASEB Journal Express Article. 2001 doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0547fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinou JC, Youle Richard J. Mitochondria in Apoptosis: Bcl-2 Family Members and Mitochondrial Dynamics. Dev Cell. 2011;21:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedeva YV, Lin B, Shuttleworth CW, Weiss JH. Intracellular Zn2+ Accumulation Contributes to Synaptic Failure, Mitochondrial Depolarization, and Cell Death in an Acute Slice Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation Model of Ischemia. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1105–1114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4604-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mina EW, Lasagna-Reeves C, Glabe CG, Kayed R. Poloxamer 188 Copolymer Membrane Sealant Rescues Toxicity of Amyloid Oligomers In Vitro. J Mol Biol. 2009;391:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1984;11:47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Pinedo C, Guio-Carrion A, Goldstein JC, Fitzgerald P, Newmeyer DD, Green DR. Different mitochondrial intermembrane space proteins are released during apoptosis in a manner that is coordinately initiated but can vary in duration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11573–11578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603007103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Marty A. Discrete changes of cell membrane capacitance observed under conditions of enhanced secretion in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:6712–6716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng R, Metzger JM, Claflin DR, Faulkner JA. Poloxamer 188 reduces the contraction-induced force decline in lumbrical muscles from mdx mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00017.2008. 00017.02008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niatsetskaya ZV, Sosunov SA, Matsiukevich D, Utkina-Sosunova IV, Ratner VI, Starkov AA, Ten VS. The Oxygen Free Radicals Originating from Mitochondrial Complex I Contribute to Oxidative Brain Injury Following Hypoxia—Ischemia in Neonatal Mice. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:3235–3244. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6303-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei L, Shang Y, Jin H, Wang S, Wei N, Yan H, Wu Y, Yao C, Wang X, Zhu LQ, Lu Y. DAPK1–p53 interaction converges necrotic and apoptotic pathways of ischemic neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2014;34:6546–6556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5119-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera MN, Lin SH, Peterson YK, Bielawska A, Szulc ZM, Bittman R, Colombini M. Bax and Bcl-xL exert their regulation on different sites of the ceramide channel. Biochem J. 2012;445:81–91. doi: 10.1042/BJ20112103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit PX, Dupaigne P, Pariselli F, Gonzalvez F, Etienne F, Rameau C, Bernard S. Interaction of the alpha-helical H6 peptide from the pro-apoptotic protein tBid with cardiolipin. FEBS J. 2009;276:6338–6354. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivovarova NB, Andrews SB. Calcium-dependent mitochondrial function and dysfunction in neurons. FEBS J. 2010;277:3622–3636. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant LD, Dowdell EJ, Dementieva IS, Marks JD, Goldstein SAN. SUMO modification of cell surface Kv2.1 potassium channels regulates the activity of rat hippocampal neurons. J Gen Physiol. 2011;137:441–454. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant LD, Marks JD, Goldstein SA. SUMOylation of NaV1.2 channels mediates the early response to acute hypoxia in central neurons. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.20054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant LD, Zuniga L, Araki D, Marks JD, Goldstein SAN. SUMOylation Silences Heterodimeric TASK Potassium Channels Containing K2P1 Subunits in Cerebellar Granule Neurons. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra84. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]