Abstract

Background

Diabetes is a risk factor for the development of cognitive impairment and possibly for accelerated progression to Alzheimer disease (AD) and other dementias, though the trajectory of cognitive decline in general and in specfic cognitive domains by diabetes is unclear.

Methods

Using the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set (NACC-UDS) to identify cohorts of elders with normal cognition (N=7,663) and Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI, N=4,114), we compared overall cognitive composite and domain specific subscores and their progression over time between diabetic and non-diabetic subjects.

Results

Diabetes was more common among those with MCI (14.7%) than among subjects who were cognitively normal (11.7%). In subjects who were cognitively normal, baseline cognitive composite scores, attention, and executive function subscores were lower in diabetics than non-diabetics (by 0.098, 0.066, and 0.015 points, respectively). Over time, cognitive composite score showed subtle worsening in non-diabetics (0.025 points every 6 months), with an additional worsening of 0.01 points every 6 months in diabetics compared to non-diabetics. In the MCI groups, baseline cognitive composite as well as attention and executive domain subscores were lower in diabetics than non-diabetics (by 0.078, 0.092, and 0.032 points, respectively). Over time, cognitive composite (by .103 points every 6 months) and all domain specific subscores showed subtle worsening in non-diabetics, but diabetics had significantly slower worsening than non-diabetics on both cognitive composite (by 0.028 points) and domain specific subscores.

Discussion

Among elders, diabetes may be associated with lower cognitive performance, primarily in non-memory domains. However it is not associated with continued worsening, suggesting a static deficit with minimal memory involvement. This data suggest that diabetes may contribute more to a vascular profile of cognitive impairment than a profile more typical of AD.

Keywords: dementia, diabetes, cognitive decline, Mild Cognitive Impairment, longitudinal analysis

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a chronic condition commonly found in the elderly, affecting approximately 20% of those 65 and older. An additional 5.9% of this age group are reported to have undiagnosed diabetes.1,2 Prevalence of diabetes has been rising rapidly across all age, sex, and racial/ethnic groups for several decades. There is strong evidence that diabetes is associated with cognitive impairment and dementia,3–12 increases the risk for Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease(AD),13,14 and increases the risk for vascular dementia.8,15–18 The nature of cognitive deficit in diabetes and its patterns of cognitive deficit and the likelihood of further decline however, are not well characterized.19–22 This characterization could contribute to our understanding of the etiology of dementia, particularly since domain-specific cognitive impairment and cognitive worsening can be associated with focal brain changes, with regional connectivity patterns associated with specific types of dementia such as AD or vascular disease. For example, amnestic versus non-amnestic deficits may suggest different etiologies and different profiles of progression.

We have previously compared cognitive status between diabetic and non-diabetic individuals who were non-demented.23 In this neuropsychologically well-characterized sample, we found that while the overall measures of cognition were lower in diabetics than non-diabetics, poorer performance in diabetics occurred primarily in non-amnestic domains such as attention, executive function, and processing speed. Domains associated with Alzheimer’s dementia such as memory and language were relatively unaffected.

In this study, we extend our baseline findings by examining the effects of diabetes on cognitive performance over time. Subjects were participants in the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center's Uniform Data Set (NACC-UDS), and are highly characterized with cognitive testing, have established clinical diagnoses, and have had multiple assessments of several cognitive domains with standardized tests. We hypothesized that diabetes would be associated with cognitive decline, but the association would be more prominent for non-memory than for memory impairment. We also hypothesized that rate of decline would be different in diabetic individuals initially diagnosed with normal cognition or MCI, therefore analyses were conducted separately for individuals with normal cognition and MCI at baseline.

METHODS

Data Source

Data are drawn from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set (NACC-UDS).24 Recruitment, participant evaluation, and diagnostic criteria are detailed elsewhere.25 Briefly, beginning in September 2005, subjects have been followed prospectively from National Institute of Aging funded Alzheimer's Disease Centers (ADCs). All ADCs enroll and follow subjects with the same standardized protocol and provide data for research through NACC. Participants were followed at approximately 12 month intervals using similar evaluations at each visit. The NACC-UDS provides systematic information on demographics, behavioral status, neuropsychological testing, medical history, family history, clinical impressions, and diagnoses using standardized forms. Informed consent was given by all subjects and their informants. Because each ADC recruits subjects with different inclusion criteria, NACC data should not be considered as population based sample.

In 2015, several significant updates were implemented in the NACC-UDS (UDS 3). The most important revisions included incorporation of the 2011 NIA-AA criteria for Alzheimer’s dementia, a diagnosis of vascular brain injury, a more detailed family history form, and an updated neuropsychological battery. The revision resulted in differences in several data elements from the previous version. To maintain data consistency, we excluded from the analytic data set the small number of subjects (2.5%) who had initial visits using UDS 3. To be eligible for the current study, participants were 65 or older at baseline, had at least one follow up visit, and were non-demented as determined by clinician consensus. The data used in current analysis are drawn from UDS subjects who were followed up since study inception in 2005 to March 2016 using data from 35 ADCs.

Measures

We categorized our sample into three groups based on their initial diagnosis: cognitively normal, amnestic MCI (aMCI), or non-amnestic MCI (naMCI).26 Cognitive status was assessed using Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) and ten neuropsychological measures in four separate domains: memory (Logical Memory IA and IIA), attention (Digit Span forward and backward, digit symbol, trail making part A), language (category fluency in animals, vegetables, Boston naming), and executive function (trail making part B). Following similar methodology from earlier studies,23,27 a normalized cognitive composite score (CC) and subscores in each domain were constructed to summarize neuropsychological measures by dividing item scores by their maximum possible scores and summing across items. Trail A and Trail B scores were reversed so that higher individual scores and therefore total CC score indicate better cognitive performance.

Diabetes (absent, recent/active, remote/inactive, unassessed/unknown) was reported based on clinician assessment of subject’s medical history at baseline. Because few subjects reported remote/inactive diabetes (n=134, 0.68%), we combined them with those who reported recent/active diabetes. Data on diabetic treatment were extracted from UDS Medication Form, which includes up to 40 medications for each subject. Lifestyle interventions were not recorded. Diabetes status was initially categorized into the following 3 groups: (1) no diabetes, (2) treated diabetes (diabetic by medical history, and listed at least one FDA approved anti-diabetic medication), and (3) untreated diabetes (diabetic by medical history, no anti-diabetic medications). But estimation results using these 3 categories showed little difference between treated and untreated diabetes. In the final set of analyses, we therefore combined treated and untreated diabetes groups. (Results using the 3 diabetes categories are included in the supplemental Tables 1 and 2). We additionally excluded the following set of subjects from the analysis sample: (1) 73 subjects (0.37%) with unknown diabetes status, (2) 65 subjects (0.31%) whose medical history reported no diabetes but listed at least one anti-diabetic medication.

Age, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic/Latino, other), and education were ascertained by self-report. History of hypertension, history of stroke, depression in the past 2 years, history of alcohol abuse, and current smoking also were ascertained by self-report. Activities of daily living were assessed using the Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ),28 and behavioral symptoms was assessed by Neuropsychiatric Inventory, short form (NPI-Q).29 Both of these are assessed in interviews with study partners.

Analysis

We first compared baseline demographic and neuropsychological characteristics by diabetes groups using Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables within each diagnosis group. Multivariable analyses were performed using mixed effects regression models for each diagnosis group separately. The dependent variables are Cognitive Composite (CC) score and its four domain subscores. Our main independent variables are indicator for diabetes and its interaction with time. We first examined longitudinal change over time using categorical variables based on annual visits, tested non-linearity in time by using continuous variables for time (days) since enrollment and adding higher order terms on time and their interactions with diabetes, and also estimated restricted cubic spline models. Results suggested that using time since enrollment as a continuous variable was the best fitting model. Because measuring time in days produces parameter estimates that are exceedingly small and difficult to read, we scaled days from enrollment into every 6 months. We also tested models that included a random slope to allow patients to differ in their overall rate of change over time. Likelihood ratio tests suggested that including a random slope did not improve model fit and was subsequently dropped. Our regression model is CC = β0 + β1 diabetes + β2 time + β12 (diabetes × time) + β4 covariates + ε. Covariates included baseline age, gender, race/ethnicity, years of education, baseline MMSE, and indicators for history of hypertension, stroke, depression, current smoking, and alcohol abuse. Indicators for NACC centers were also included in the estimation models to control for differences by site. Specified as such, the coefficient on diabetes (β1) estimates baseline differences between diabetics compared to non-diabetics. We hypothesized that diabetics would have lower baseline performance compared to non-diabetics (β1<0). We also hypothesized that cognitive performance (for non-diabetics) would worsen over time (β2<0). Our main interest is the coefficient β12, which estimates difference in the rate of change in diabetics compared to non-diabetics. If β12 is statistically insignificant, this indicates rate of change in CC is similar in diabetic and non-diabetic subjects over time. If β12 is negative, this indicates faster rate of decline in CC in diabetics compared to non-diabetics. If β12 is positive, this indicates slower rate of decline in CC in diabetics compared to non-diabetics.

Because subjects were followed over time, cluster robust standard errors were reported. All analyses were performed using Stata 13.0. Statistical significance was set a priori at p<0.05 without adjusting for multiple comparisons.30

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

The analysis sample included 7,663 subjects who were initially cognitively normal, 3,347 aMCI, and 767 naMCI subjects. There were significantly higher proportions of diabetics in naMCI (17.2%, n=132) and aMCI groups (14.1%, n=473) than in the cognitively normal group (11%, n=899) (p<0.01, Table 1). In the cognitively normal group, those with diabetes were younger, more likely to be male, more likely to be Hispanic or black, and had lower education compared to those without diabetes. Similar differences were seen in aMCI and naMCI groups, except that differences in proportions of males were not statistically significant in either MCI groups. Within each diagnosis group, those with diabetes were more likely than non-diabetics to report having hypertension or having had a stroke. Interestingly, history of depression was higher in diabetics than non-diabetics in the normal group, but not significantly different in either MCI groups. Compared to non-diabetics, diabetics had worse baseline NPI-Q and FAQ scores, but differences were statistically significant only in the normal group. On average, follow up years were 5.0±2.5, 4.1±2.0, and 4.1±2.0 for cognitively normal, aMCI, and naMCI groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Diagnosis Group and Diabetes Status.

| Cognitively Normal |

All MCI | Amnestic MCI |

Non-amnestic MCI |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes status | No | yes | p | No | yes | p | No | yes | p | No | yes | p |

| N | 6,764 | 899 | 3509 | 605 | 2,874 | 473 | 635 | 132 | ||||

| Composite Score | 5.62 | 5.2 | <0.001 | 4.71 | 4.47 | <0.001 | 4.65 | 4.42 | <0.001 | 4.76 | 4.4 | 0.002 |

| (0.86) | (0.96) | (0.90) | (0.96) | (0.90) | (0.98) | (0.89) | (1.01) | |||||

| Age, mean(sd) | 75.7 | 75.0 | 0.015 | 76.7 | 76.0 | <0.001 | 76.6 | 75.4 | 0.002 | 75.2 | 74.1 | 0.120 |

| (7.2) | (6.6) | (7.0) | (6.4) | (6.9) | (6.4) | (6.7) | (6.2) | |||||

| Male, % | 34.9 | 39.6 | 0.004 | 50.3 | 55.0 | 0.039 | 51.9 | 55.5 | 0.084 | 44.5 | 49.2 | 0.152 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 80.7 | 55.6 | <0.001 | 81.1 | 57.0 | <0.001 | 81.8 | 59.2 | <0.001 | 78.0 | 49.2 | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12.5 | 31.7 | 10.3 | 27.1 | 10.2 | 24.9 | 11.0 | 34.8 | ||||

| Hispanic | 4.5 | 10.0 | 5.7 | 10.6 | 5.1 | 9.9 | 8.3 | 12.9 | ||||

| Other | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 5.3 | 2.9 | 5.9 | 2.7 | 3.0 | ||||

| Education, mean(sd) | 15.7 | 14.7 | <0.001 | 15.3 | 14.0 | <0.001 | 15.4 | 14.5 | <0.001 | 15.1 | 13.8 | 0.001 |

| (3.0) | (3.4) | (3.3) | (3.8) | (3.3) | (3.7) | (3.5) | (4.1) | |||||

| Stroke, % | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.001 | 5.6 | 11.0 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 2.1 | <0.001 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0.023 |

| Hypertension, % | 48.2 | 79.3 | <0.001 | 52.9 | 82.0 | <0.001 | 49.9 | 79.5 | <0.001 | 50.8 | 83.1 | <0.001 |

| Depression, % | 14.9 | 17.6 | 0.014 | 30.6 | 32.0 | 0.464 | 30.4 | 32.4 | 0.172 | 30.4 | 26.6 | 0.305 |

| Current smoker, % | 3.5 | 4.6 | 0.111 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0.971 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 0.772 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 0.839 |

| NPIQ, mean(sd) | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.003 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 0.087 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.074 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 0.778 |

| (1.7) | (2.3) | (3.0) | (3.2) | (3.0) | (3.0) | (3.1) | (3.6) | |||||

| FAQ, mean(sd) | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.032 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 0.446 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 0.994 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 0.055 |

| (1.5) | (1.7) | (4.9) | (5.1) | (4.5) | (4.7) | (3.9) | (4.9) | |||||

| Follow up years, mean (sd) | 5.1 | 4.7 | 0.002 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 0.130 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 0.059 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 0.559 |

| (2.5) | (2.4) | (7.0) | (6.4) | (2.1) | (1.8) | (2.0) | (1.9) | |||||

In the cognitively normal group, CC and all neuropsychological measures were worse in diabetics than non-diabetics at baseline (all p<.001). In the aMCI group, CC, executive function, language, and attention composite scores were worse in diabetic compared to non-diabetics at baseline. However, memory composites were similar between diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Of particular interest, delayed recall was better in diabetics than non-diabetics among the aMCI group. Patterns in the naMCI group were similar to those found in aMCI groups, except that diabetics and non-diabetics had similar scores on memory domain and category fluency. (Detailed comparisons between groups are included in supplemental Table 3.)

Composite Cognitive Scores over Time

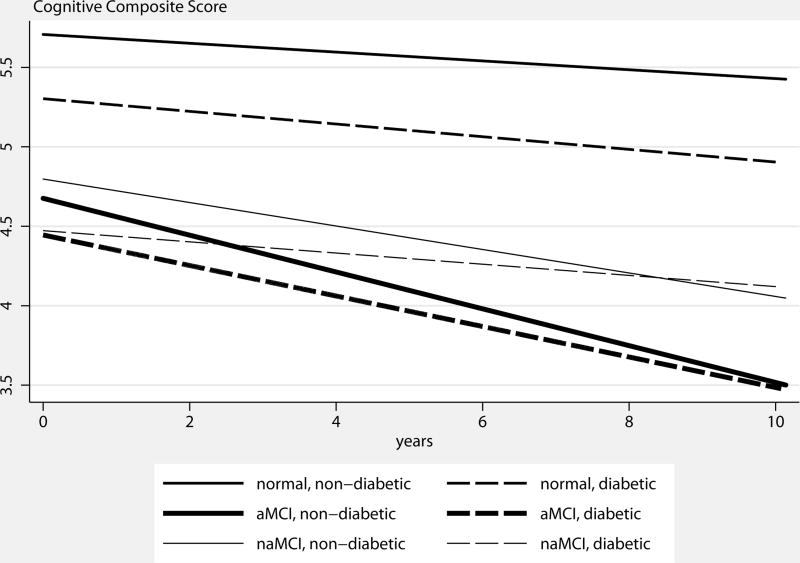

Table 2 reports estimated effects of diabetes on CC score by diagnosis groups, after controlling for other covariates. Predicted CC scores by diagnosis group and diabetes status are shown in Figure 1. In the cognitively normal group, diabetics had an average of 0.098±0.025 points lower on the CC than non-diabetics at baseline. There was a small but significant negative interaction between diabetes and time, indicating accelerated decline in diabetics compared to non-diabetics. Specifically, CC declined in non-diabetics by an average of 0.025±0.001 points every 6 months. In diabetics, CC declined by an additional 0.010±0.003 points every 6 months (all p<.01). In the aMCI group, diabetics had 0.074±0.033 points lower in CC score than non-diabetics at baseline (p<.05). There was a small but significant positive interaction between diabetes and time, indicating slower decline in diabetics than non-diabetics. Specifically, CC declined in non-diabetics by an average of 0.111±0.003 points every 6 months. In diabetics, however, rate of decline in CC was slower by 0.020±0.008 points every 6 months (both p<.05). In the naMCI group, baseline CC scores were similar between diabetics and non-diabetics. Over time, CC declined by an average of 0.070±0.006 points in non-diabetics every 6 months. In diabetics, however, rate of decline in CC was slower by 0.038±0.014 points every 6 months than non-diabetics (p<.05).

Table 2.

Random Effects Regression Results of Effects of Diabetes on Composite Cognitive and Domain Specific Subscores by Diagnosis groups.

| Cognitive Composite |

Memory | Attention | Language | Executive Function |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitively Normal | Diabetes | −0.098 | −0.013 | −0.066 | −0.005 | −0.015 |

| (0.025)** | (0.011) | (0.013)** | (0.006) | (0.006)** | ||

| Time | −0.025 | 0.008 | −0.018 | −0.009 | −0.010 | |

| (0.001)** | (0.001)** | (0.001)** | (0.000)** | (0.000)** | ||

| Diabetics × Time | −0.010 | 0.001 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | |

| (0.003)** | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001)+ | (0.001)* | ||

|

| ||||||

| All MCI | Diabetes | −0.078 | 0.034 | −0.092 | −0.008 | −0.032 |

| (0.038)* | (0.015)+ | (0.018)** | (0.011) | (0.011)** | ||

| Time | −0.103 | −0.017 | −0.046 | −0.033 | −0.028 | |

| (0.003)** | (0.001)** | (0.001)** | (0.001)** | (0.001)** | ||

| Diabetics × Time | 0.028 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.006 | |

| (0.007)** | (0.003)** | (0.003)** | (0.002)** | (0.002)** | ||

|

| ||||||

| aMCI | Diabetes | −0.074 | 0.030 | −0.093 | −0.007 | −0.030 |

| (0.033)* | (0.016)+ | (0.020)** | (0.012) | (0.012)* | ||

| Time | −0.111 | −0.018 | −0.049 | −0.036 | −0.029 | |

| (0.003)** | (0.001)** | (0.001)** | (0.001)** | (0.001)** | ||

| Diabetics × Time | 0.020 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.003 | |

| (0.008)* | (0.003)* | (0.004)** | (0.002)** | (0.003) | ||

|

| ||||||

| naMCI | Diabetes | −0.070 | 0.042 | −0.066 | −0.006 | −0.039 |

| (0.085) | (0.031) | (0.040)+ | (0.024) | (0.025) | ||

| Time | −0.070 | −0.011 | −0.034 | −0.019 | −0.022 | |

| (0.006)** | (0.002)** | (0.003)** | (0.002)** | (0.002)** | ||

| Diabetics × Time | 0.038 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.014 | |

| (0.014)** | (0.006)+ | (0.007) | (0.004) | (0.005)** | ||

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01

Coefficient on diabetes estimates baseline difference in outcome for diabetic compared to non-diabetic group. Coefficient on time estimates average change in outcome over 6 months in the non-diabetic group. Coefficient on diabetes × time estimates average differences in change over 6 months in diabetic group compared to non-diabetic group.

Covariates include baseline MMSE, age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, history of hypertension, depression, stroke, smoking and drinking, and indicators for site.

Figure 1.

Predicted Cognitive Composite Score, by Diabetes Status and Diagnosis Group

In all diagnosis groups, higher CC (better cognitive performance) was associated with higher baseline MMSE, younger age, being female, white, non-Hispanic, higher education, and no history of stroke, or depression.

Domain Specific Performance over Time

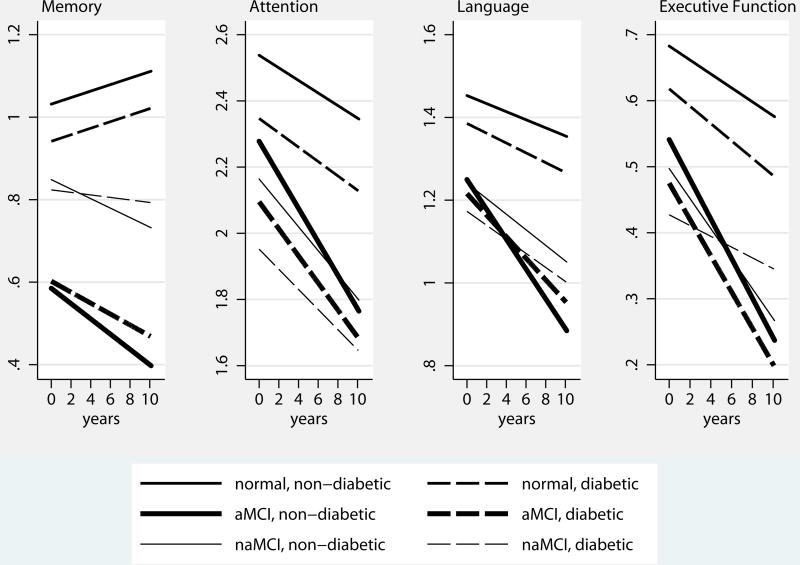

Table 2 also reports estimated effects of diabetes on performance in memory, attention, language, and executive function domains by diagnosis groups. Predicted domain specific subscores by diagnosis group and diabetes status are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Predicted Domain Specific Subscores, by Diabetes Status and Diagnosis Group

In the cognitively normal group, diabetics had lower scores at baseline in attention and executive function domains (by −0.066±0.013 and −0.015±0.006 points, respectively) than non-diabetics, but had similar scores in memory and language domains. Over time, in non-diabetics, subscores on attention, language, and executive function domains declined significantly, but memory subscores improved. There was a small but significant negative interaction between diabetes and time for language and executive function domains, indicating an accelerated decline in these domains in diabetics compared to non-diabetics.

In the aMCI group, diabetics had lower scores in attention and executive function domains than non-diabetics at baseline, but similar scores in memory and language domains. In non-diabetics, all domain subscores declined over time. There was a small but significant positive interaction between diabetes and time in memory, attention, and language domains, indicating slower decline in diabetics in these domains than non-diabetics.

In the naMCI group, diabetics and non-diabetics had similar scores in all sub-domains. In non-diabetics, all domain specific subscores declined over time. There was a small but significant positive interaction between diabetes and time in executive function domain, indicating slower decline in diabetics than non-diabetics.

Sensitivity Analyses

Because subjects may differ systematically by length of follow up, we compared subjects’ characteristics for those who had 1, 2, or 3+ follow up assessments. In subjects who were cognitively normal at baseline, there were 1,193, 941, and 3,194 non-diabetic and 168, 147, and 344 diabetic subjects who have had 1, 2, or 3+ follow up assessments, respectively. Subjects who were followed up longer were slightly older at baseline (76.7±7.3 in those with 3+ follow up vs. 75.9±7.6 in those with 1 follow up), less likely to be male (34.3% in those with 3+ follow up vs. 35.2% in those with 1 follow up), and white (87.1% in those with 3+ follow up vs. 79.0% in those with 1 follow up), but there was no systematic differences in baseline diabetes status by length of follow up. Similar differences were observed in aMCI and naMCI subjects. To examine whether estimated effects differed for subjects with different lengths of follow up, we re-estimated the same models using subsamples by length of follow up. Results were remarkably consistent with those reported here, providing confidence that these results are not biased from different lengths of follow up.

DISCUSSION

In this study we compared longitudinal trajectories of cognitive performance in a well-characterized national sample of non-demented subjects with and without diabetes. We found significantly more diabetics in MCI groups compared to the group with normal cognition. In all diagnosis groups, at baseline, diabetics had worse overall cognitive performance than non-diabetics. Over time, performance in cognitive composite declined in non-diabetics. In the normal cognition group, diabetics had a slightly faster rate of decline compared to non-diabetics. Perhaps surprisingly, in MCI groups, diabetics had a slightly slower rate of decline compared to non-diabetics.

After adjusting for demographic and clinical features, our examination of specific cognitive subdomains showed that in the memory domain, there was no significant difference between diabetics and non-diabetics at baseline in any diagnosis groups. In the cognitively normal group, there was a small improvement over time, with no differential rate of decline between diabetics and non-diabetics. In the MCI groups however, there was a small decline over time in memory in non-diabetics, but the rate of decline seemed to be mitigated in diabetics. In all non-memory domains, performance at baseline was worse in diabetics than non-diabetics. Over time, in all diagnosis groups, performance in all non-memory domains declined in non-diabetics. In the cognitively normal group, diabetics had a slightly faster rate of decline over time compared to non-diabetics in language and executive function domains. In MCI groups, diabetics showed significantly less deterioration than non-diabetics in all domains.

Taken together, our results suggest that a static deficit of diabetes may be present in this cohort. The trend toward an improvement in memory suggests that this deficit may be non-amnestic in nature. The slower rate of deterioration in diabetics also suggests a static deficit rather than a progressive one. It is important to note that although results reported here are statistically significant, the magnitudes of these effects are small.

If diabetes is suspected to be a risk factor for AD, one might predict that diabetics’ performance in cognitive testing would be similar to those with MCI. Rather, the deficits observed were primarily non-amnestic in nature, with attention and executive function domains significantly affected in diabetic subjects. As such, distinct cognitive profiles suggest distinct underlying biology. It is worth noting that in cross-sectional analyses, diabetes was associated with a lower score in most cognitive domains. This could inflate epidemiologic estimates of cognitive impairment and dementia among diabetics, particularly when cognitive screening techniques are used for detection. Alternatively, as diabetics are at increased risk for small-vessel disease, which has been shown to impair prefrontal cortex processing tasks such as executive function and attention, our findings are consistent with several earlier reports,31,32 and support a model of cognitive decline due to the association of diabetes with vascular disease.

There are several limitations of the study. First, this highly educated volunteer group who participated in research at NIA-supported ADCs may not be representative of the general population. In particular, this cohort likely under-represents the prevalence and severity of diabetes in the general population and may have characteristics that can mitigate the effect of diabetes on cognition. For example, better education may help individuals improve diabetic control and lifestyle modification, and may reduce the impact of diabetes on cognitive impairment. Second, we are reporting on cognitive scores without regard to whether they reflect clinically significant deficits. Third, report of diabetes is based on medical history and is without confirmatory laboratory results. That being said, previous studies have shown that self-reported physician-diagnosed diabetes has strong reliability.3 Confidence in the classification of diabetics vs. non-diabetic diagnosis also is increased by corroborating data on diabetic medication treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table S1. Baseline Cognitive Performance by Diagnosis group and Diabetes Status

Supplemental Table S2. Random Effects Regression Results of Effects of Diabetes on Composite Cognitive Score by Diagnosis groups, separating effects of treated and untreated diabetes

Supplemental Table S3. Random Effects Regression Results of Effects of Diabetes on Memory, Attention, Language, and Executive Function Subscores, separating effects of treated and untreated diabetes

Acknowledgments

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI Marie-Francoise Chesselet, MD, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), and P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Footnotes

SPECIFIC DISCLOSURES

Dr. Zhu: None

Dr. Sano: serves on a scientific advisory board for Medivation, Inc.; serves as a consultant for Bayer Schering Pharma, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Elan Corporation, Genentech, Inc., Medivation, Inc., Medpace Inc., Pfizer Inc, Janssen, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, and United Biosource Corporation; and receives research support from the NIH (NIA/NCRR).

Dr. Grossman: None

Dr. Schimming: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Sano: study concept or design; revising the manuscript; interpreted data.

Dr. Zhu: drafted/revised the manuscript, assisted in study concept or design, analyzed/interpreted data,

Dr. Grossman: contributed to study concept and design, revising the manuscript.

Dr. Schimming: revising the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | Mary Sano | Carolyn Zhu | Hillel Grossman | Corbett Schimming | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Board Member | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Personal Relationship | x | x | x | x | ||||

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rates of Diagnosed Diabetes per 100 Civilian, Non-Institutionalized Population by Age United States, 1980–2014. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregg EW, Yaffe K, Cauley JA, et al. Is diabetes associated with cognitive impairment and cognitive decline among older women? Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 2000 Jan 24;160(2):174–180. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fontbonne A, Berr C, Ducimetiere P, Alperovitch A. Changes in cognitive abilities over a 4-year period are unfavorably affected in elderly diabetic subjects: results of the Epidemiology of Vascular Aging Study. Diabetes Care. 2001 Feb;24(2):366–370. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cukierman T, Gerstein HC, Williamson JD. Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetes--systematic overview of prospective observational studies. Diabetologia. 2005 Dec;48(12):2460–2469. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassing LB, Grant MD, Hofer SM, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus contributes to cognitive decline in old age: a longitudinal population-based study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004 Jul;10(4):599–607. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704104165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okereke OI, Kang JH, Cook NR, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cognitive decline in two large cohorts of community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Jun;56(6):1028–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, et al. Association of diabetes with amnestic and nonamnestic mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2014 Jan;10(1):18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinkohl I, Keller M, Robertson CM, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in older people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015 Jul;58(7):1637–1645. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3581-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinkohl I, Price JF, Strachan MW, Frier BM. The impact of diabetes on cognitive decline: potential vascular, metabolic, and psychosocial risk factors. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0130-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ojo O, Brooke J. Evaluating the Association between Diabetes, Cognitive Decline and Dementia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015 Jul;12(7):8281–8294. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120708281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Formiga F, Ferrer A, Padros G, et al. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for functional and cognitive decline in very old people: the Octabaix study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014 Dec;15(12):924–928. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akomolafe A, Beiser A, Meigs JB, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of developing Alzheimer disease: results from the Framingham Study. Arch Neurol. 2006 Nov;63(11):1551–1555. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.11.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer disease and decline in cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004 May;61(5):661–666. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knopman D, Boland LL, Mosley T, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2001 Jan 9;56(1):42–48. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Berg E, de Craen AJ, Biessels GJ, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG. The impact of diabetes mellitus on cognitive decline in the oldest of the old: a prospective population-based study. Diabetologia. 2006 Sep;49(9):2015–2023. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruis C, Biessels GJ, Gorter KJ, van den Donk M, Kappelle LJ, Rutten GE. Cognition in the early stage of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009 Jul;32(7):1261–1265. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wessels AM, Lane KA, Gao S, Hall KS, Unverzagt FW, Hendrie HC. Diabetes and cognitive decline in elderly African Americans: a 15-year follow-up study. Alzheimers Dement. 2011 Jul;7(4):418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanz C, Andrieu S, Sinclair A, Hanaire H, Vellas B Group RFS. Diabetes is associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009 Oct 27;73(17):1359–1366. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd80e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biessels GJ, Strachan MW, Visseren FL, Kappelle LJ, Whitmer RA. Dementia and cognitive decline in type 2 diabetes and prediabetic stages: towards targeted interventions. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology. 2014 Mar;2(3):246–255. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strachan MW, Price JF. Diabetes. Cognitive decline and T2DM--a disconnect in the evidence? Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014 May;10(5):258–260. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Cesari M, Liu F, Dong B, Vellas B. Effects of Diabetes Mellitus on Cognitive Decline in Patients with Alzheimer Disease: A Systematic Review. Canadian journal of diabetes. 2016 Sep 7; doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandipati S, Luo X, Schimming C, Grossman HT, Sano M. Cognition in non-demented diabetic older adults. Current aging science. 2012 Jul;5(2):131–135. doi: 10.2174/1874609811205020131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, et al. The National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007 Jul-Sep;21(3):249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006 Oct-Dec;20(4):210–216. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004 Sep;256(3):240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cosentino SA, Stern Y, Sokolov E, et al. Plasma ss-amyloid and cognitive decline. Arch Neurol. 2010 Dec;67(12):1485–1490. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982 May;37(3):323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000 Spring;12(2):233–239. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feise RJ. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC medical research methodology. 2002 Jun 17;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacKnight C, Rockwood K, Awalt E, McDowell I. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia, Alzheimer's disease and vascular cognitive impairment in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;14(2):77–83. doi: 10.1159/000064928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schimming C, Luo X, Zhang C, Sano M. Cognitive performance of older adults in a specialized diabetes clinic. Journal of diabetes. 2016 Nov 03; doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table S1. Baseline Cognitive Performance by Diagnosis group and Diabetes Status

Supplemental Table S2. Random Effects Regression Results of Effects of Diabetes on Composite Cognitive Score by Diagnosis groups, separating effects of treated and untreated diabetes

Supplemental Table S3. Random Effects Regression Results of Effects of Diabetes on Memory, Attention, Language, and Executive Function Subscores, separating effects of treated and untreated diabetes