Abstract

Reducing obesity positively impacts diabetes and cardiovascular risk; however, evidence-based lifestyle programs, such as the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), show reduced effectiveness in African American (AA) women. In addition to an attenuated response to lifestyle programs, AA women also demonstrate high rates of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. To address these disparities, enhancements to evidence-based lifestyle programs for AA women need to be developed and evaluated with culturally relevant and rigorous study designs. This study describes a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to design a novel faith-enhancement to the DPP for AA women. A long-standing CBPR partnership designed the faith-enhancement from focus group data (N=64 AA adults) integrating five components: a brief pastor led sermon, memory verse, in class or take-home faith activity, promises to remember, and scripture and prayer integrated into participant curriculum and facilitator materials. The faith components were specifically linked to weekly DPP learning objectives to strategically emphasize behavioral skills with religious principles. Using a CBPR approach, the Better Me Within trial was able to enroll 12 churches, screen 333 AA women, and randomize 221 (Mage=48.8±11.2; MBMI=36.7±8.4; 52% technical or high school) after collection of objective eligibility measures. A prospective, randomized, nested by church, design will be used to evaluate the faith-enhanced DPP as compared to a standard DPP on weight, diabetes and cardiovascular risk, over a 16-week intervention and 10-month follow up. This study will provide essential data to guide enhancements to evidence-based lifestyle programs for AA women who are at high risk for chronic disease.

Background

Reducing obesity is strongly associated with reductions in diabetes and cardiovascular risk [1]. Modest weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) trial was associated with a 58% reduction in diabetes risk [2]; however, the DPP has shown reduced effectiveness in African American (AA) populations [3, 4] that also experience higher rates of obesity[5], diabetes [6], and hypertension [7, 8] compared to Caucasians. Faith based organizations (FBO), such as churches, have been extensively involved in the delivery of health programs in AA communities. Programs have been implemented through faith-placed, secular programs held at an FBO, and faith-based, which integrates faith-based activities such as scripture into health programming [9]. A large review of FBO weight loss studies in AA found that faith-placed programs resulted in greater weight loss than faith-based programs that integrated faith elements, indicating that additional research is needed to identify best practices [9]. Further, a review of DPP program translations for AA found reduced effectiveness; approximately half of the expected weight loss from the original study [3]. Taken together, more research is needed to develop effective enhancements to health programs for AA [9, 10].

One approach that may improve the effectiveness of health programs for AA is community-based participatory research (CBPR). CBPR works to build an equitable partnership between the community, and research team, with a long-term commitment to develop the relationship through co-learning leading to mutual trust and respect [11]. In the context of CBPR, community members and leaders work together on all aspects of the research study leading to quality research, community empowerment, and sustainable programs with lower rates of attrition and synergy over time [12, 13].

Psychosocial and physiological factors can also influence the effectiveness of health programs. For example, allostatic load, a composite of several biological measures representing dysregulation due to prolonged exposure to stress, has been shown to increase the “wear and tear” on the body [14], with data showing allostatic load is higher in AA as compared to White females [14, 15]. Further, the influence of sex hormones such as estradiol on stress responses are not fully understood and could alter responses to intervention [16–18]. The reduced effectiveness of diabetes prevention programs in AA may be multifactorial requiring a systems approach to implementation and evaluation.

The Better Me Within trial aims to address the lack of effectiveness of diabetes prevention programs in AA females by integrating a CBPR approach to design and implement a randomized trial of a faith-enhanced diabetes prevention program in the FBO setting. The design allows for comparison of faith-based as compared to faith-placed approaches along with mediators and moderators of outcomes. This paper describes study development, methodology, recruitment, and baseline demographics of the study sample.

Methods

Study Aims

The primary aim of the Better Me Within trial is to evaluate the impact of a CBPR developed faith-enhanced diabetes prevention program (e.g., faith-based) as compared to a standard diabetes prevention program (e.g., faith-placed) on weight in AA overweight females at 16-weeks post-intervention, and at 10-month follow-up. Secondary aims include evaluating changes in diabetes risk (hemoglobin A1c and fasting glucose), cardiovascular disease risk (blood pressure, LDL and HDL cholesterol), and health behaviors (physical activity and diet) at 16-weeks between the faith-enhanced DPP and standard DPP conditions, and how psychosocial factors such as self-efficacy and spiritual health locus of control, and physiological factors such as cortisol and estrogen, influence changes in primary and secondary outcomes.

Study Development

The CBPR partnership that guided the development and implementation of the Better Me Within trial had been in existence for approximately 10 years. The partnership included researchers, individuals trained in public health, and a Community Advisory Board (CAB) of several pastors and first ladies from the Southern Sector of Dallas, TX. Based on the findings of a large NIH funded study (GoodNEWS trial) to improve cardiovascular risk guided by this CBPR partnership [19, 20], it was determined that weight management was the next community health priority to address. Formative work was conducted through focus groups to evaluate AA women’s needs, preferences, and barriers to weight management, along with preferences and opinions of church leaders including pastors, first ladies, and pastor associates.

Seven focus groups with 64 AA adults including 53 female congregation members (mean age = 44.0 (SD=11.3) years; 95% African American) from six congregations, and 7 pastors and 4 first ladies (mean age = 56.3 (SD=13.6) years; 100 % African American) were conducted in the Southern Sector of Dallas, TX, an urban, low-income, primarily ethnic minority community. The purpose of the focus groups was to determine the perspectives of church leaders and church members on the relationship between faith and health, as well as, weight loss and maintaining a healthy lifestyle, to guide the development of a faith-enhanced lifestyle program. Gathering input directly from community members, in addition to community leaders, has been shown to improve the outcomes of behavioral interventions [10]. Using directed content analysis [21] to group participant statements, the following broad categories were identified: 1) Connections between faith beliefs and health, 2) Attitudes, values and motivations for weight management, 3) Hurdles to healthy weight, and 4) Elements for successful weight loss. Specific strategies from these themes included 1) focus on diabetes and chronic disease prevention, 2) address food habits and motivation, 3) pastor involvement in the program was critical but needed to be realistic from a time perspective, and 4) emphasize connections between faith and health. These findings were presented to the CAB and used to develop the faith-enhanced weight management program for the Better Me Within trial.

Study Design

The Better Me Within trial is a prospective randomized community-based, nested design. Churches were randomized to either a standard diabetes prevention program (faith-placed) or a faith-enhanced diabetes prevention program (faith-based) over 3 years, starting in January of 2014, and completing in December of 2016. Each year, 4 churches were recruited and randomized to treatment condition, for a total of 12 churches. Small churches were paired during the randomization process within each cohort to ensure one received the standard DPP, and the other the faith-enhanced DPP, as church size can influence study implementation. A limitation of this approach is church size was only accounted for at the cohort level. Baseline data collection was completed in July of 2016. The Institutional Review Board at The University of North Texas Health Science Center approved the study. Informed consent was collected from each study participant prior to enrollment.

Church Recruitment

The CBPR partnership recruited churches from October of 2013 to February of 2016. Church inclusion criteria included 1) church size greater than 100 members, 2) primarily African American parishioners, 3) willingness of pastor or senior leadership to be involved in program delivery, 4) church member willing to serve as a facilitator (e.g., health coach), and 5) space to conduct weekly group meetings. Pastors and first ladies from the CAB led initial recruitment efforts by contacting churches within their social and professional networks. Once a church demonstrated interest, the project director and CAB partner would meet with church leadership to provide an overview of the program. During this meeting the purpose of the BMW trial was described as well as the roles and responsibilities of the church and study program. A commitment by the pastor reserved a spot in the study. The pastor then selected a woman or women from the congregation to serve as the health coach(es), and coach training was scheduled. This was repeated each year until a total of 12 churches were enrolled in the study.

Participant Recruitment

Pastors and health coaches received flyers and program factsheets to distribute at church events and to interested church members. Participants were pre-screened by telephone or at face-to-face events by study staff, and were then invited to a baseline measurement event at their corresponding church. Informed consent was collected at baseline measurement events along with objective measures of eligibility (e.g., weight, height, hemoglobin A1c). Participant eligibility requirements included 1) identify as AA, 2) female, 3) 18 years of age or older, 4) parishioner at enrolled church, 5) overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25), and 6) willingness to participate in a 10-month study. Exclusion criteria included 1) currently attending a weight loss program, 2) diagnosed diabetes, 3) medical condition that interfered with physical activity or dietary changes, and 4) plans to move in the next 10 months. Individuals who were not eligible to participate were invited to attend the sessions if room was available to meet the preferences of the CBPR partnership.

Interventions

Faith Enhanced Diabetes Prevention Program (Faith-DPP). The faith-enhanced curriculum was faith-based and developed using CBPR approaches where focus group findings provided community level input that was then used by The Better Me Within CAB to develop the faith-enhanced curriculum. The faith-enhanced curriculum was developed by the CAB, with edits from the research team provided after development. The Faith-DPP condition included delivery of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), an evidence-based lifestyle enhancement program from the Centers for Disease Control that has been evaluated in large randomized controlled trials [2, 22]. The group intervention was delivered by one to two trained peers from the church and consisted of 16 weekly group meetings followed by 6 bi-monthly or monthly maintenance sessions. Each church received approximately 10 months of programming that included a group intervention, participant and facilitator handouts, and supplies. Participants completed a private weigh-in with their facilitator on a medical grade digital scale followed by an hour and a half faith-enhanced DPP group intervention.

The faith enhanced curriculum included five strategies: 1) a mini sermon (~15 minutes in length) delivered by a pastor (head pastors were required to deliver at least one per month), first lady, or church leader (pastor associate, deacon, elder, etc.), 2) a memory verse, 3) in class or take-home faith activity (application of faith principles), 4) promises to remember, and 5) scripture and prayer integrated into participant curriculum and facilitator materials. These five faith enhancements were developed by the CAB to enhance the DPP’s weekly learning objectives, which resulted in faith components specifically linked to each week of DPP content. The DPP learning objectives, faith-enhanced learning objectives and content are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Faith-DPP and Standard DPP Curriculum

| Standard DPP Curriculum Learning Objectives | Faith Learning Objectives | Mini-Sermon Summary | Memory Verse | Faith Activity/Homework | Promises to Remember | Scripture References Faith Handout & Devotional |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Week 1: Welcome to the National DPP - Describe purpose and benefits - Describe session content - Weight loss and physical activity goals established by the National DPP - Develop individual weight loss and physical activity goals - Importance of self-monitoring |

We are created by God. God is the Creator; therefore, He is the sustainer. We are sustained by God’s Word. |

The Purpose for a Better Me Within -Define biblical health, how to set a vision by looking to God and scripture -Describes health principles that lead to improved physical health and improved spiritual health -Biblical health is a state of physical and spiritual well-being -Possible through faith in Jesus Christ. |

Psalm 119:73 | Create a Vision Board | Ephesians 3:20 Proverbs 3:5–10 -Full and abundant life begin with seeking God’s plan for our lives. -Developing a vision for healthy living requires preparation through spending time in God’s Word and seeking obedience. -We have purpose because we know Christ. Live in that purpose through seeking and obeying God’s Word. |

Acts 27:34 Deuteronomy 32: 47 Ecclesiastes 3:11 Genesis 43:28 Isaiah 58:8 Jeremiah 30:17; 33:6 Proverbs 3: 1–2,5–10; 4:22; 12:18; 13:17; 29:18 Psalm 42:11; 43:5; 67:2; 119:73 1 Peter 1:2 2 Samuel 20:9 |

|

Week 2: Be A Fat & Calorie Detective - Self-monitor weight - Document weight at home and at each session - Relationship between fat and calories - Reasons and basic principles of self-monitoring fat grams/calories -Identify personal fat gram goals -Practice using the Fat and Calorie Counter -Record daily fat grams -Calculate fat, calories, & serving sizes from nutrition labels |

The plan for A Better Me Within begins with our steps being ordered by God. -Accepting God as the source of our wisdom, knowledge and strength -Receiving Biblical instruction for good health - Following the Biblical principles of good health |

The Plan for a Better Me Within -God’s plan for how to use our bodies discussing biblical principles for good physical, mental, and spiritual health and the importance of understanding how being obedient to God’s commands can benefit our health -Specific scriptures highlighting health are included -God designed our body as a finely tuned, resilient instrument that can endure constant use and even pain/trauma, but it is fragile |

Exodus 15:26 | Matching activity to identify scriptures about actions/behaviors that lead to good health. During the week: Meditate/pray that God will help you to incorporate the principles in the Faith Activity in your life. |

Ephesians 3:20 Romans 9:33b Become a Conscience Calorie Counter and Stay within Fat Gram Budget “with God all things are possible” (Mark 10:27). Jesus is ready to break the shackles that bind us (John 1:12). Christ is for our joy “These things have I spoken unto you … that your joy might be full” (John 15:11). |

1 Corinthians 10:31 2 Corinthians 7:1 Deuteronomy 6:24; 14:1–3 Ecclesiastes 12:13 Exodus 15:26; 23:25 Ezekiel 11:18–19 Galatians 6:7 Genesis 1:29, 2:16, 3:18 Hebrews 4:13 Isaiah 55:2 James 4:17 John 14:15; 15:11 1 John 2:5; 3:3 3 John 1:2 Proverbs 3:1–2,8 Psalm 84:11 Romans 4:12 |

|

Week 3: Reducing Fat and Calories -Weigh and measure foods -Estimate the fat and calories of common foods -Describe three ways to eat less fat and fewer calories -Create a plan to eat less fat the following week |

Remember God has placed high value on each of us. Your body is a temple you have received from God. Therefore honor God with your bodies by first acknowledging and then embracing your positive characteristics and qualities. |

Building a Queenly Body Fit for The King -Biblically motivate ourselves to eat less fat and fewer calories -Honor the body because it is a temple of Holy Spirit (being mindful to measure food accurately, and watch portion sizes) -Physical and spiritual are connected so do not neglect one for the other -Educate yourself to know what is best for body and spirit (practice discipline in tracking fat grams & spiritual health) - Develop a plan for success (use technology or resources to assist you in monitoring your food intake) |

1 Corinthians 6:19–20 | List 10 positive characteristics or qualities (Individually or small group) Homework: Meditate on meaning of “body to be a temple of the living God”. -Impact on your life? -Review positive characteristics. How can these to propel your journey in the BMW Program? |

Knowledge Is Power for Knowing What’s Best for Me Plan What We Eat To Develop Discipline within Me Make Better Choices with Self-Motivation for Me | 1 Corinthians 6:19–20 3 John 1:2 1 Peter 3:3–4 Proverbs 14:1 Proverbs 23:7 |

|

Week 4: Healthy Eating -Health benefits of eating less fat and fewer calories - MyPlate food guide & recommendations - Compare/contrast guidelines with current eating habits -List ways to replace high-fat & high-calorie with low-fat & low-calorie foods -Importance of whole grains, vegetables, fruits, within fat gram goals -Eat foods from all groups -Eat a variety of foods -Eat a balanced diet |

God has given us free will. He has prepared for us scriptural solutions to guide us through challenges and questions. |

Replace Eating the Spiritually Fat for Eating the Spiritually Lean -Bible can motivate us to eat healthy - Healthy eating is determined both by what we eat and how we eat - By incorporating plant-based foods and avoiding excess fat our physical health improves. - Our spiritual health improves by feeding our spirit-Matthew 4:4 “Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God. |

Genesis 1:29 | Word Search to identify Exodus 23:25 “I will take sickness away from among you” During the week: What are some changes you have been able to make in BMW with the help of God? What of your unwise choices would you be willing to trade for a healthier choice? |

Knowledge Is Power for Knowing What’s Best for Me Making wise choices Develops Discipline within Me Knowing I’m never alone is Self-Motivation for Me | 1 Corinthians 6:19–20 Exodus 23:25 Genesis 1:29 3 John 1:2 Leviticus 7:23–24 Matthew 4:4 1 Peter 3:3–4 Proverbs 23:7 |

|

Week 5: Move Those Muscles -Establish physical activity goal -Importance of physical activity goal -Describe current level of physical activity -Name ways already physically active -Develop personal plans for physical activity for the next week. |

Believers must live out the command to glorify God in our bodies and in our spirits. |

The Provision for the Better Me Within -How to start treating your body like God’s temple through remembering the Holy Spirit dwells in you -Exercising wisdom in making decisions about food, training your body physically and gaining in godliness - Trust God’s promise that godliness is profitable now and forever |

I Corinthians 6:19–20 | Find a partner and pray for each other to be victorious as you begin the physical activity component of BMW. Helpful scriptures (Matthew 26:41, John 6:63, Romans 8:26) Homework: Write down names of group members & commit to pray for each other this week. |

START MOVING Acts 17:28 “For in Him, we live and MOVE and have our being” START TRAINING I Timothy 4:7–8 “Have nothing to do with godless myths and old wives’ tales; rather train yourself to be godly. For physical training is of some value, but godliness has value for all things, holding promise for both the present life and the life to come.” |

Acts 17:28 1 Corinthians 6:19–20 John 6:63 Matthew 26:41 Proverbs 23:1–2, 19–21, 29–32 Romans 8:26 1 Timothy 4:7–8 |

|

Week 6: Being Active: A Way of Life -Graph daily physical activity -Describe two ways to find time to be active -Define “lifestyle activity” -How to prevent injury -Develop an activity plan for the coming week. |

God is faithful to provide all things to persevere in physical activity. |

The Promises For A Better Me Within -Summarizes many of the promises in the bible that can help to transform our health -One of the titles of God is Jehovah Jireh, The Lord My Provider. - By focusing on promises of blessing, abundance, health and peace listed we can battle the weight of daily life (defeat, poverty, despair, sickness hopelessness, etc.), and achieve & sustain the goals we set for health (being active and eating well). |

Isaiah 40:31 | Get in groups of 2–3 and pray for each other to be victorious in physical activity this week. | Review the Promises of Blessing, Abundance, Health and Peace from the mini-sermon (Worksheet). | Deuteronomy 8:18; 28:6,8 Isaiah 26:3; 40:31;58:8 Jeremiah 29:11; 30:17 John 1:16; 14:27; 16:33 3 John 2 Malachi 3:10 Numbers 6:26 Proverbs 10:22; 28:20 Psalm 4:8; 31:19; 34:19; 35:28;102: 2–3; 103:2–3 |

|

Week 7: Tip the Calorie Balance -Define calorie balance -Explain how eating and being active are related to calorie balance - Relationship between calorie balance & weight loss - Describe progress as it relates to calorie balance - Develop an activity plan for the coming week |

Imbalanced means out of proportion, unstable, instable, disturbed, unhinged. God has purpose for all things to balance at a proper time. We must submit to the balance God has for us because when we choose our own direction, life becomes imbalanced and unbalanced. |

Balance Provides Purposeful Living -How to biblically motivate ourselves to tip the calorie balance A few ways to help us identify balance in our spiritual life and live healthy are: Feast at the proper time (Ecclesiastes 10:17), refrain from indulging daily (Daniel 10:3), and exercise wisdom considering your food carefully (Proverbs 23:1–31). |

Ecclesiastes 10:17 | Illustration activity from Health Coach with Discussion | Knowledge Is Power For Knowing What’s Best For Me Plan What We Eat To Develop Discipline Within Me Make Better Choices With Self-Motivation For Me | 1 Corinthians 15:58 Daniel 10:3 Ecclesiastes 10:17 Philippians 3:19 Proverbs 23:1–31 Psalm 46:1 1 Samuel 26:23 |

|

Week 8: Take Charge of What’s Around You -Recognize positive and negative cues - Change negative food and activity cues to positive cues -Add positive cues for activity and eliminate cues for inactivity -Develop a plan for removing one problem food cue for the coming week |

Revealing is Revelation. |

Develop the Good within You, in order to Control What Is around You -How to be “like-minded” with Jesus to enable us to take charge of what’s around us -Changing your Attitude (Mindset) become aware of the many factors that influence our behavior related to eating and activity (Philippians 2:5) - Changing your Affiliation (Environment)-identify and change negative food and activity cues into positive cues (2 Corinthians 5:17) - Changing your Acquaintance (Authority) by adding positive cues for activity (James 4:7–8) |

James 4:7–8 | Participant matching activity led by the coach to help participants find commonality with one another. | Knowledge Is Power For Knowing What’s Best For Me Plan What We Eat To Develop Discipline Within Me Make Better Choices With Self-Motivation For Me | 2 Corinthians 5:17 James 4:7–8 1 John 3:16 Mark 13:13 Philippians 2:5 Proverbs 17:17 |

|

Week 9: Problem Solving -List and describe five steps to problem solving -Apply five problem solving steps to resolve a problem with eating less fat and fewer calories or being more active. |

Dependence upon God and the Scriptures is key to learning the process of problem solving which aids is the desirable outcome of a Better Me Within. |

Problems Are Opportunities Waiting to Happen -How to view problems and create solutions through applying our faith -Scripture makes it clear that there will be problems and suffering in our lives -Several steps are outlined to assist with problem solving including: get the facts (Proverbs 18:13), be open to new ideas (Proverbs 18:15); hear all sides (Proverbs 18:17). |

James 1:5 | Journal how God is helping you problem solve: Step 1: Be honest & specific in written account of problem (Proverbs 12:17). Step 2: Brainstorm Your Options; depend on God (Proverbs 3:4–6). Step 3: Pick 1 Option to Try; ask God to instruct you. (James 1:5–8) Step 4: Make a plan (Jeremiah 32:18b–19) Step 5: Try It; Have faith God will not let you fail. (Romans 8:28) |

Remember these scriptures when you face problems-Matthew 10:24 and Romans 8:17–18. When we are in a difficult place, recall to mind how God has delivered you before Jesus is sufficient for everything, everybody, and in every circumstance. |

James 1:2–5 John 16:33 Matthew 11:28 Proverbs 3:4–6; 18:13, 15, 17 Psalm 145:14 Romans 8:28 2 Thessalonians 1:5 |

|

Week 10: Healthy Eating Out -List and describe the four keys for healthy eating out -Give examples of how to apply these keys at restaurants participants go to regularly -Make an appropriate meal selection from a restaurant menu -Demonstrate how to ask for a substitute item using assertive language and a polite tone of voice |

We are reduced to choice makers. Choose you this day, which appetite you will satisfy? |

What Would Jesus Eat -Principles of eating from the Bible and the availability of certain foods during biblical times. -The possible diet of Jesus based on his period of life is discussed as well as the importance of health in scripture. -Suggestions are described to plan for meals and eating out. |

1 Corinthians 6:12 | Discussion questions- How will you appropriate God’s Word to free you from your former way of thinking about eating out? What changes are you willing to make to do this? Memorize one of the verses presented in this lesson. Before you go out to eat, pray the Scripture, asking God to strengthen you as you go out to eat. |

-As our Lord did, always remember to respond rather than react to life. The more we practice responding the more likely it is to become a life principle. -Let your choices be guided by the Holy Spirit. -Reliance upon God’s Word enables you to resist temptation and follow in obedience. -When facing temptation, we always have a choice and God always provides a way of escape. |

1 Corinthians 3:16–17; 6:12,19–20; 9:27; 10:31 Deuteronomy 6:24 Ecclesiastes 2:22–23; 3:13; 5:12; 10:17 Exodus 20:9.10; 23:25 Genesis 1:29; 2:16; 3:18 Isaiah 52:11; 55:2 3 John 1:2 Luke 21:34 Matthew 5:23–24 Proverbs 14:30; 17:22; 23:2,7 Psalm 84:11; 127:2 |

|

Week 11: Talk Back to Negative Thoughts -Give examples of negative thoughts that interfere with losing weight and being more physically active -Describe how to stop negative thoughts and talk back to them with positive thoughts -Practice 1) stopping negative thoughts and 2) talking back to negative thoughts with positive ones |

Talk BACK! … to the negative |

With Christ All Things Are Possible For Me -How to recognize and fight negative thoughts. -Negative thoughts can be habitual. -Keys to changing negative thoughts are to remember truth through scripture “I can do all things through Christ” (Philippians 4:13), counter them with positive thoughts (Romans 4:17), and ask for help from Jesus through prayer; he can help in our time of need (Psalm 61:1–2). |

Psalm 61:1–2 | List 1 thing in your journal/notes that is a habitual negative thought. Look at it carefully and prepare a response for it and say it out loud. Take time in class to share your negative thoughts with the group, and help one another with encouraging words to battle the negative thought. |

I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me Calls those things which do not exist as though they did The most power antidote for negative thoughts is to stop them mid-sentence and counter them with positive thoughts and prayer. |

Mark 5:8 Philippians 4:13 Psalm 61:1–2 Romans 4:17; 7:18–23 |

|

Week 12: Slippery Slope of Lifestyle Change -Describe their current progress toward defined goals -Describe common causes for slipping from healthy eating or being active -Explain what to do to get back on their feet after a slip |

Slips Happen … Take Time To Learn From Them |

I’ve Fallen Down and I Can Get UP! -How to recover after a slip. -When you slip there is hope and you can receive help from God to regain control. -Remember these steps: slipping off the path to healthy eating and physical activity is natural (Proverbs 24:16); don’t give up, keep a positive attitude, and regain control as soon as possible (Philippians 4:13); slips are opportunities to learn (Philippians 4:12). |

Proverbs 24:16a | Try to build a house of cards; discuss this activity with the Health Coach and apply it to slips in life. Find passages in scripture that can encourage you when a slip occurs. Write them down, and put them in a place where you can see them regularly |

Slips are Opportunities to Learn When You Slip Don’t Give Up Slipping Is Natural, Normal and Usual…Learn From It, Refocus and Move On | Philippians 4:12–13 Proverbs 24:16 |

|

Week 13: Jump Start Your Activity Plan -Describe ways to add interest & variety to activity plans -Define aerobic fitness -Explain the four F.I.T.T. principles (frequency, intensity, time, and type of activity) and how they relate to aerobic fitness |

Remain steadfast. Persevere and press on. |

What Makes You Move? -Getting to know God better through reading scripture, and being obedient to God can have a positive impact on our health physically, mentally and spiritually. -Practical steps to apply your faith and encourage physical activity are outlined. - Benefits such as being able to serve the Lord are also described. |

Isaiah 40: 29–31 | In each Scripture on the worksheet, list the promises and conditions. Share with others how you can be obedient and God can fulfill the promise to you. Ask the Lord to help you to discover new ways to “stay the course” and to increase your activity to greater heights of fitness and physical strength. |

Though our bodies are wasting away daily, we are encouraged to be good stewards of God’s gift to us, our bodies, by achieving a balance that promotes both spiritual and physical health. A regular physical activity routine in addition to a healthy eating plan significantly reduces the risk of many diseases and helps us to maintain optimum well-being. | Colossians 2:20–23 1 Corinthians 6:19–20 Galatians 6:9 Isaiah 40:29–31 James 1:25 Mark 12:30 Matthew 11:28–29; 18:21–22 Philippians 4:13 Proverbs 3:7–8; 14:30 Psalm 119:93,143 Romans 12:1–2 1 Samuel 16:7 1 Thessalonians 5:17 1 Timothy 4:8 |

|

Week 14: Make Social Cues Work for You -Examples of problem and helpful social cues -How to remove problem social cues and add helpful ones -Describe ways of coping with vacations, social events, holidays, & visits -Create an action plan to replace problem social cue with helpful one |

Learn to conquer the war within. |

Who’s Influencing You? -How to reflect on our cues (social, environmental, physical) to help us identify habits and patterns that lead to poor health habits. -By identifying these cues, new patterns for positive health can be established. - Examples from Jesus’ life are used to show how his purpose influenced his response to situations. -A challenge is given to plan for situations with a response and practice it to create new habits. |

2 Corinthians 10:3–5 Ephesians 6:13–18 |

Use your vision board or create a new one and apply the armor of God from Ephesians 6 to it. Review scriptures that are applicable to each type of armor and, write them on your board. Use them to help you combat negative social cues. | The power of a purpose is our motivation to always be prepared to respond rather than react. Having a planned response to negative social cues will assist in forming new habits. | 1 Corinthians 6:19–20 2 Corinthians 10:3–5 Ephesians 2:10; 5:18; 6:13–18 Isaiah 62:5 John 14:23 Philippians 2:14 Romans 12:2 |

|

Week 15: You Can Manage Stress -How to prevent or cope with stress -Program can be stressful -How to manage stress -Action plan for preventing/coping with stress |

Your Worship can defeat the war of stress. |

Your Walk Is Your Warrior Against Worry (Stress) -How to overcome the effects of stress by putting to practice simple coping tools for life. -One illustration is through worship. -Job’s life is used as an example through this section. |

Job 1:20 | Identify a stress point in your life. How can you handle it through worshipping God? List 3 of worship stances and share with the class. | The Victory of the War is in your Worship Seek God first for directions for me Develop coping tools that help me Maintain a healthy lifestyle that supports me |

Job 1:11,20; 6:6–7 Matthew 6:25–34 Psalm 1; 40:1–3; 55:1–7 |

|

Week 16: Ways to Stay Motivated -Measure progress toward weight and physical activity goals -Develop a plan for improving progress, if goals have not yet been attained -Describe ways to stay motivated long-term |

You can do it!!!!! |

Knowledge Is Power to Motivate The Unmotivated -How to stay motivated to live a healthy and blessed lifestyle. -The example of David is used to show how he prayed and remembered the promises of God in times of discouragement and fear. - A deep connection to God can keep us motivated when our own efforts begin to falter. |

1 Samuel 30:6 | Write 10 reasons or strategies to keep yourself encouraged and motivated. | Remind yourself of your strength in the Lord! Motivation Comes From Within Me When I Have The Holy Ghost Within Me Knowledge Is Power That Transforms Me Success Is Achievement That Surpasses Me Progress Is Forward Movement That Motivates Me |

1 Samuel 30:6,8 Psalms 121:1 |

Standard Diabetes Prevention Program (S-DPP)

The S-DPP condition was faith-placed, a secular program (the DPP) held at an FBO. This condition received the same Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) as the Faith-DPP, but did not receive any faith enhancements or pastor involvement. Weekly learning objectives are shown in Table 1.

Coach Support

In both interventions, health coaches participated in weekly communications with a research staff member via email or conference call depending on need. Weekly communication sessions reviewed: 1) curriculum and supplies needed, 2) participant progress based on weekly weights, attendance, and receipt of food logs, and 3) participants experiencing difficulties or barriers. Coaches were reminded to stay in communication with participants and complete make-up sessions with absent participants through verbal, text, and email reminders.

Training

One research staff member was trained by the Diabetes Training and Technical Assistance Center (DTTAC) at Emory University. This trained individual created a coach training for church members who facilitated the group intervention. The training included an overview of the original DPP trial, review of 16 CORE sessions, facilitator roles and responsibilities, facilitation skills, DPP core elements, food tracking 101, process evaluations, classroom logistics, troubleshooting and warning signs of dropout, identifying the circumstances and environment of participants struggling with pre-diabetes or overweight/obesity, hands-on practice with food tracking, role playing and facilitating a lesson. Training was 12 hours long and was conducted over 2 – 3 sessions depending on the church’s schedule. Facilitators also received a booster training session (2–4 hours) prior to the Maintenance phase of the program. All facilitators attended the training or a make-up session before implementation.

Pastors also attended one training module that provided an overview of the program and curriculum, research principles, and expectations for church, health coaches and university staff. Specific training components were tailored based on group assignment. The S-DPP Pastors reviewed the DPP curriculum and discussed how to support the program at their church. The Faith-DPP pastors were given an overview of the faith components that were added to the DPP, received instructions and samples of the sermonettes and lesson plans.

Measures

Participants attended measurement events at their respective churches where food was offered after completion of fasting measures, celebratory music was played, church staff were present, and a small monetary incentive was provided ($20 gift card at baseline and 16-weeks, $40 gift card at 10-month follow-up). All measurement devices and tools were transported by study staff to church sites. Measures were collected by trained and blinded research staff that attended a two hour training prior to measurement events for instruction and hands-on practice. Measures were conducted at baseline, 16 weeks post-intervention, and a limited battery at 10 month follow-up (see Table 2). Reliability and validity of primary and secondary measures are described in Table 2. Participants completed standard surveys on demographic, medical history, medication use (type, and dose), last two menstrual cycles, and menopausal status. The following are descriptions of primary and secondary measures expected to change due to the DPP intervention.

Table 2.

Anthropometric (Primary*) and Secondary Measures

| Measure | Timepoint | Instrument | Description | Validity | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight* | 0, 16 week, 10-month | Doran Digital Scale DS6100 | Measured twice to the nearest 0.1 lbs, averaged | -- | -- |

| Height* | 0, 16 week, 10-month | Seca 213 Stadiometer | Measured twice to the nearest 0.01 inches, averaged | -- | -- |

| Waist Circumference (WC) | 0, 16 week, 10-month | Tape measure | Measured twice with inelastic tape to the nearest 0.1cm using NIH Guidelines [40]. | r=0.62 for correlation between WC and visceral abdominal tissue among women [41] | r=0.998 for intraclass correlation in females [42]. |

| Blood Pressure | 0, 16 week, 10-month | Omron Digital Blood Pressure Monitor (HEM-907XL) | Measured twice to the nearest 1 mmHg, averaged | -- | -- |

| Blood Lipids | 0, 16 week | Cholestech LDX system | Measures fasting blood lipids and glucose profiles from blood sample collected via finger stick | TC, r =0.92; TRG, r = 0.93; HDL, r =0.92; LDL, r =0.86; with Lab values [43]. | ρ > 0.75 ICC for all 4 lipid categories [44]. |

| HbA1c | 0, 16 week | Bayer A1cNow+ Multi-Test A1c System | HbA1c measure collected via finger stick | r = 0.893 with Laboratory results [45]. | Sensitivity 0.95, specificity 0.74, positive predictive value 0.85, negative predictive value 0.91 [45]. |

| Diet | 0, 16 week, 10-month | Delta NIRI (short FFQ) | 158-item questionnaire designed to assess African Americans food intake patterns [24] | Statistical correlations in energy intake were demonstrated between Delta short FFQ and 24-hour dietary recalls [24] | Energy adjusted correlations for macronutrient and micronutrient intakes between the short FFQ and 24-hour dietary recalls ranged from 0.13 – 0.54 [24] |

| Physical Activity | 0, 16 week, 10-month | Past Week Modifiable Physical Activity Questionnaire | Self-report duration and type of physical activities completed in the past week | r = 0.51 with pedometer [46]. | r= 0.74 ICC for test-retest reliability [26] |

| Physical Activity | 0, 16 week, 10-month | Yamax Power Walker Ex-510 Pedometer | Pedometer that stores daily step counts | r = 0.98 with manual count [47]. | Cronbach’s α =0.992 [48]. |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 0, 16 week | 4mL Saliva, ELISA assay method in ZRT Lab | Saliva collected in 4 consecutive weeks and sent to a laboratory to assay | r = 0.71 with serum sample [49, 50]. | CV = 5.2% in interassay [50] |

| Cortisol (ng/mL) | 0, 16 week | 4mL Saliva, EIA assay method in ZRT Lab | Fasting morning saliva sent to a laboratory to assay | r = 0.81 with serum sample [51, 52]. | CV = 2.2% in interassay [53]. |

Anthropometrics

Weight (primary measure) (lbs) was collected with a digital scale in light clothing with shoes removed. Height (inches) was collected with a stadiometer. Weight and height were collected twice and the average was computed. BMI (weight/(height2) × 703) was calculated from the averaged height and weight data. Waist circumference was taken at the top of the pelvis (e.g., above the uppermost lateral border of the right ilium) with a measuring tape twice and averaged.

Diabetes Risk

Risk for diabetes was measured with a fasting blood sample obtained by finger stick. Fasting glucose was measured with the Cholestech LDX system, and glycated hemoglobin A1C was measured with Bayer A1cNow+ Multi-Test A1c System.

Cardiovascular Risk

Markers of cardiovascular risk were measured with a fasting blood sample obtained by finger stick with the Cholestech LDX system and included low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), total cholesterol, and triglycerides. Blood pressure was collected with an automated blood pressure device following a seated 5 minute rest in a quiet area. Two measurements were taken following Eighth Joint National Committee [23] protocols and averaged.

Dietary Patterns

Diet was measured with the Lower Mississippi Delta Nutrition Intervention Research Initiative (Delta NIRI) food frequency questionnaire, developed initially for the Jackson Heart Study, that measures typical dietary intake patterns including energy intake (kcals), fat (saturated and unsaturated) grams, sugar, carbohydrates, protein, fiber, and fruits and vegetables [24, 25]. The Delta NIRI was developed specifically for AA populations, and has strong correlations with 24-hour dietary recalls, but is less expensive to administer [24]. Data is scanned and analyzed by Northeastern University’s Dietary Assessment Center.

Physical Activity

Physical activity was measured by self-report with the Past Week Modifiable Physical Activity Questionnaire [26]. Objective physical activity was collected over a week time period using the YAMAX digi-walker.

Additional measures including physiological and psychosocial variables hypothesized to mediate the effect of the intervention on primary and secondary outcomes were collected, and are described below.

Physiological Variables

Saliva samples were collected over 4-weeks (one fasting sample for cortisol and estradiol; 3 non-fasting weekly samples of estradiol to determine peak level over a month time period), and were stored in a sub-zero freezer to measure fasting morning cortisol (ng/mL), and estradiol (E2, pg/mL). Samples were mailed to a CLIA compliant laboratory, where samples were centrifuged and assayed.

Psychosocial Variables

Constructs hypothesized to be mediators or predictors of primary and secondary outcomes were measured with reliable and valid self-report surveys at baseline, 16-weeks, and 10 months, see Table 3 for detailed descriptions.

Table 3.

Psychosocial Measures (collected at baseline, 16-weeks, and 10 months)

| Measure | Description | Construct Validity | Reliability Coefficient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Image | Body Appreciation Scale | 13-item scale for assessing positive body image [54]. | Exercise frequency correlated with higher positive body image in women with low to average levels of appearance-based physical activity motivation [55] | Cronbach’s α =0.93 [56]. |

| Pulvers Figure Rating Scale | Figure rating scale with 9 silhouettes developed to examine body image perception and obesity relationship in African Americans [56]. | Ratings of body image strongly correlated with participants’ BMI’s [56]. | Inter-rater reliability Cronbach’s α = 0.95 [56]. | |

| Self-Efficacy | Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire- Short Form (WEL-SF) | 8-item eating self-efficacy instrument derived from validated 20-item WEL questionnaire [57]. Assesses degree of confidence to resist overeating. | WEL-SF items strongly correlated with the original validated WEL.4 WEL-SF items overall represented difficulty resisting eating in the presence of increased food availability, social pressure, negative emotions, physical discomfort, and positive activities [57]. | Pearson’s r value=0.968 for correlation between WEL-SF and the full version of WEL [57]. |

| Self-efficacy for Exercise Behaviors Scale [58]. | 12 items, measures degree of confidence to exercise despite certain barriers. 2 subscales: resisting relapse (5 items) & making time for exercise (7 items) [58]. | Change in exercise self-efficacy significantly correlated with weight loss 4 months postintervetion [59]. | Cronbach’s α = 0.85 resisting relapse.5 Cronbach’s α = 0.83 making time for exercise [58]. |

|

| Physical Activity and Nutrition Self-Efficacy (PANSE) Scale | 11-item instrument used to assess weightloss self-efficacy among lower-income postpartum women [60]. | Increases in weight-loss self-efficacy (PANSE) scores significantly correlated with reduced unhealthy behavior practices [60]. | Cronbach’s α coefficient of r = 0.89 [60]. | |

| Health Locus of Control | Spiritual Health Locus of Control | 13-item scale with 2 subscales: active (11 items) & passive (2 items). Evaluates spiritual locus of health responsibility [61]. | Active spiritual beliefs were positively associated with fruit consumption and negatively associated with alcohol consumption. Passive spiritual beliefs were associated with lower vegetable and increased alcohol consumption [61]. | Active subscale internal consistency r=0.88 for female subjects [61]. Passive subscale internal consistency r=0.58 for female subjects [61]. |

| Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) Form A | 18-item measure with 3 dimensions that assess individuals’ Internal (I scale), Powerful Others (P scale) and Chance (C scale) Loci of Control to capture general beliefs about their perceived internal and external control over their health [62, 63]. | Almost all of pure internal group (99%) reported their health as very good or good compared to the yea-sayer group (87%) [63]. | Coefficient α = 0.85, 0.75 and 0.71 for I, P, and C scales respectively [63]. | |

| Motivation | Intrinsic Motivation for Diet and Physical Activity | 19-item instrument derived from validated scales used in other studies. 2 subscales: Intrinsic Motivation for Diet and Intrinsic Motivation for Physical Activity. | Motivation for physical activity and fruit & vegetable intake significantly increased post-intervention [64, 65]. | Reliability coefficient = 0.53 diet11 Reliability coefficient = 0.78 physical activity [64]. |

| Mood | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CESD-10) Scale | 10 items, screens for depressed mood symptoms [66, 67]. | Overweight and obesity categories were shown to be positively associated, and physical activity negatively associated with depressive symptoms at 3-year follow up [67]. | r= 0.71 for test-retest item correlation of CESD-10 with CESD-20 [66]. |

| Stress | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) [68, 69]. | 10 items, measures the degree of stress perception. | Using multiple regression analysis, perceived stress significantly predicted responses for emotional eating and haphazard meal planning [69]. | Internal reliability (Cronbach alpha coefficient =0.78) [68]. |

| Social Support | Weight Management Support Inventory (2 scales: Frequency and Helpfulness scales) | 52-item inventory: 26 items each on Frequency and Helpfulness subscales. Assesses frequency and helpfulness of social support for weight loss [70] | Both frequency and helpfulness of supportive behaviors were demonstrated to be significantly associated with restrained eating [70]. | For frequency scale test-retest reliability r= 0.75; for helpfulness scale test-retest reliability r= 0.80 [70]. |

A process evaluation protocol was developed to ensure fidelity to treatment assignment, and evaluate dose of treatment received and participant satisfaction, as described below.

Process Evaluations

Process evaluations were developed to measure dose and fidelity to program implementation based on previously published models [27]. Churches were evaluated approximately once per month during the 16 week intervention by independent trained raters. During the maintenance phase, churches were evaluated approximately once per month. Dose measured whether predetermined intervention components were delivered (response YES or NO), such as completion of weigh-in, distribution of materials, checking for food and physical activity tracking, and reviewing learning objectives. The criterion for achieving dose was at least 75% of program components successfully delivered. Fidelity measured if program components were delivered as expected on a 1 – 4 point likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater fidelity. Fidelity was assessed for behavioral skills, communication skills, social support, session content (including the faith-based component in the Faith-DPP group). The criterion for achieving fidelity was a mean of 3.0 on the assessed variables. Additional process evaluation measures included participant attendance, and satisfaction measured at post-intervention with an 8-item self-report survey.

Data Analysis

The primary objective of this study is to assess the impact of a CBPR developed faith-enhanced diabetes prevention program (Faith-DPP) as compared to a standard diabetes prevention program (S-DPP) in AA overweight women on decreasing body weight (in lbs) at two assessment periods: 1) at 16 weeks (post-intervention) 2) at 10 months (maintenance). As the treatment groups were randomized at the church (cluster) level, subjects within a church must be considered dependent (nested) observations. Therefore, a multilevel model will be used where the treatment group will be analyzed as a fixed factor and the church as a random factor to account for the hierarchical structure of the design. We will assess treatment effects in terms of weight loss (in lbs) from baseline to 16 weeks and from 16 weeks to 10 months using separate multilevel models. Baseline weight will be entered in the model as a covariate to account for the longitudinal design of the study as suggested by Wilson et al. [28]. Variables that were significantly different at baseline will be included as covariates in all models. Using the notation of Raudenbush and colleagues [29], the model for the 16-week and 10-month assessments will be:

Level 1 (Between subjects effect).

where, Yij is change in weight from baseline of participant i in church j (j = 1, 2, …, 11). β0j is the adjusted mean change of weights in church j after controlling for all other variables. Whereas, β1 and βc are fixed level-1 effect of weight (Wi) at baseline and other covariates for the ith subjects; and ri is the subject level error term, which is assumed to be normally distributed.

Level 2 (Treatment effect).

where, Tj is a treatment indicator variable (1=intervention, 0=control), γ00 is the adjusted mean change of weight in the control group churches, and γ01 is the treatment effect. γ10 and γc0 are the pooled within-church regression coefficients for the level-1 covariates; and u0j is an error term representing a unique effect associated with church j, and it is assumed to be normally distributed.

Our primary purpose in fitting this model is to examine the treatment effect in reducing body weight after adjusting for baseline weight, education level, annual household income, comorbidities, age, menopausal status, smoking status, alcohol consumption in the last 30 days, and hemoglobin A1c level. We will estimate a parsimonious model that best fits the data. To do so, we will start with an unconditional model (with no predictors) to estimate the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to explain how much variation in weight loss is explained by level-2 units (churches). After that, we will gradually build a complex model that best fits the data. Likelihood ratio test will be used as a measure of model fit along with AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) and BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion). A model accounting for church level effects such as church size and fidelity to intervention determined by process evaluations will also be conducted.

Analysis plan for secondary aims. Several multilevel models will be fit to address the secondary aims to compare S-DPP and Faith-DPP on reducing risk factors for cardiovascular disease (blood pressure, HDL and LDL cholesterol) and diabetes (hemoglobin A1C), and change in behavioral factors (diet, exercise) in AA overweight women at 16-week post-intervention, and at 10-month follow-up periods. The effect of psychosocial (e.g., self-efficacy, spiritual locus of control, support) and physiological (cortisol, estrogen) variables will be tested with mediation analysis to determine the influence on primary and secondary outcomes [30, 31].

Missing Data

Multiple imputation will be used to estimate the missing values. Multiple imputation is a standard technique for imputation [32] and appropriate for cluster randomized trials that provide unbiased estimate of the parameter and its standard error under the assumption that data is missing at random [32, 33]. We will make several attempts during data collection to reduce the attrition rate. We will perform Little’s test [34] to evaluate the assumption of whether data is missing at random or completely at random for the main outcome variable (weight) and the confounding variables (comorbidities, socio-economic status, demographics etc.). After confirming that the data is missing at random we will identify predictors of attrition to use as covariates in the multiple imputation model.

Power Analysis

Priori power analyses were conducted to attain a power of at least 80% with 0.05 level of significance for the primary statistical analysis. We used the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) as 0.03 among the churches using the data from The GoodNEWS Trial, a community based study, conducted in the same geographic location [19]. We used the effect size of 0.50 (a medium effect size), which is the overall standardized mean differences of weight loss, from a meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials on weight loss through diet and exercise intervention by Wu, Gao, Chen and van Dam [35]. Standardized mean difference between two groups is equivalent to ‘effect size’ as defined by Cohen [36]. Based on these numbers, a power analysis was conducted through simulation using the SAS code provided by Donner and Klar [37] for a cluster randomized trial. It was estimated that 12 churches with 20 participants in each church (N=240) were needed to attain at least 80% power. A goal of 25 participants per church was set to account for a 20% attrition rate. The overall study goal was to recruit 300 participants, 150 in each intervention group, to attain at least 80% power.

Study Participants

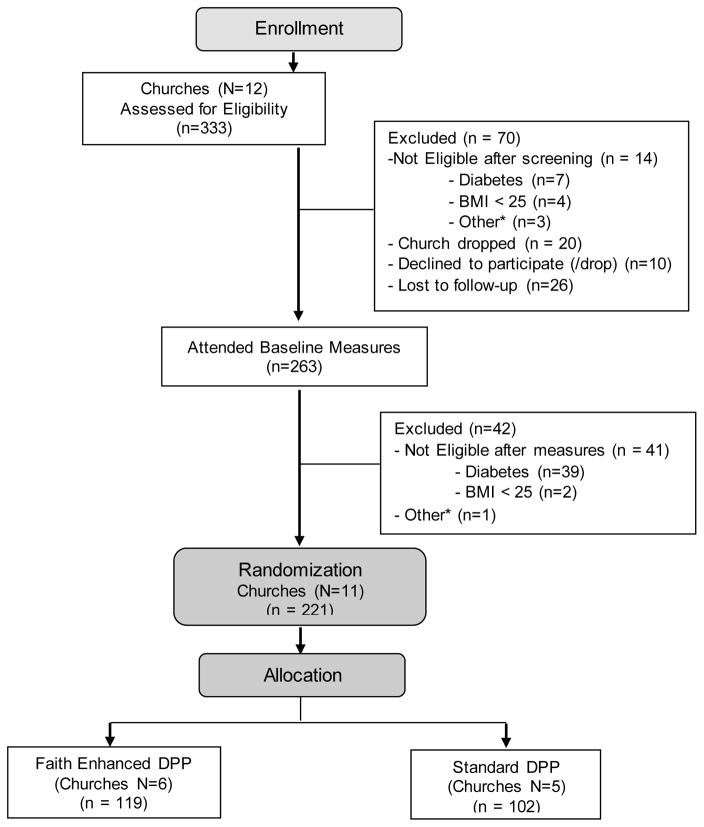

Figure 1 displays the consort flow chart for the Better Me Within Trial. 12 churches were recruited and 333 females were screened by telephone or in-person to determine initial eligibility. Of those 333 females, 14 were ineligible from pre-screening, 56 did not attend the in-person baseline measurement, and 263 were pre-eligible and attended an in-person baseline measurement event at their church. Women who did not attend in-person measures (n=56) had lower self-reported BMI (p<.01) and were younger (p<.01) than women who attended baseline measures. After objective collection of measures to determine eligibility, 221 individuals were enrolled in a treatment condition based on their church’s randomization assignment. During the enrollment process, one of the 12 churches dropped from the study due to lack of capacity to enroll at least 20 women. Overall, the consort flow chart shows minimal attrition throughout the enrollment and randomization process.

Figure 1. Better Me Within CONSORT Diagram.

*Other: Participant readiness, current weight program, moving out, medical condition that interferes with diet or physical activity change, pregnant

Table 4 shows the baseline characteristics of enrolled participants in the Better Me Within trial. Participants in the S-DPP and Faith-DPP were on average, middle-aged, obese, and had an elevated waist circumference. Although recruitment for this study targeted overweight women to improve lifestyle, participants in both the S-DPP and Faith-DPP had HbA1c in the pre-diabetic range. Significant baseline differences were found between the two groups that were consistent across several variables. Women in the Faith-DPP were better educated, had higher incomes, better HDL cholesterol, and lower HbA1c levels than women in the S-DPP group. All other baseline variables were non-significant between groups. Outcome analysis models will control for statistical significant baseline differences.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled participants

| Faith Enhanced DPP | Standard DPP | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD), n (%) | |||

| n | 119 | 102 | |

| Weight (lb) | 212.2 (47.75) | 218.3 (53.47) | |

| Waist circumference (inch) | 40.7 (6.1) | 42.0 (6.04) | |

| BMI | 36.0 (7.70) | 37.44 (9.18) | |

| Age (year) | 48.0 (10.27) | 49.8 (12.27) | |

| Education* | High school or less, n (%) | 7 (6.2) | 25 (26.3) |

| Technical degree or less than college, n (%) | 35 (31.0) | 41 (43.2) | |

| College degree or more, n (%) | 71 (62.8) | 29 (30.5) | |

| Annual Income* | $24,999 or less, n (%) | 12 (10.7) | 28 (29.2) |

| $25,000–$49,999, n (%) | 37 (33.0) | 31 (32.3) | |

| $50,000–$75,000, n (%) | 23 (20.6) | 24 (25.0) | |

| $75,000 or more, n (%) | 40 (35.7) | 13 (13.5) | |

| SBP | 128.1 (17.8) | 128.4 (20.89) | |

| DBP | 83.2 (11.02) | 81.2 (10.45) | |

| Hypertension (SBP>=140 or DBP>=90) | Yes | 38 (32.5) | 27 (27.0) |

| No | 79 (67.5) | 73 (73.0) | |

| HDL* | 57.9 (14.94) | 53.6 (12.66) | |

| LDL | 97.5 (26.85) | 103.8 (26.6) | |

| TRG | 113.3 (67.41) | 112.9 (47.82) | |

| TC | 175.4 (30.06) | 177.9 (31.39) | |

| FG | 88.5 (10.38) | 91.4 (12.81) | |

| HbA1C* | 5.9 (0.52) | 6.2 (0.67) | |

p<.05

Study Implications

Due to the growing health disparities and reduced effectiveness of health promotion programs such as the DPP in AA communities, culturally relevant enhancements to evidence-based approaches need to be tested with rigorous study designs to inform public and population health approaches [3, 10]. With rising chronic disease rates and healthcare costs, practical and sustainable programs need to be evaluated. To our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial evaluating a faith-placed standard DPP program as compared to a CBPR developed, faith-based DPP program. The Better Me Within faith-enhanced curriculum is novel by connecting faith-components to weekly DPP behavioral and learning objectives to strategically emphasize behavioral principles through multiple integrated faith components. Another novel component of the faith enhanced curriculum is the addition of a brief pastor led sermon connected to each DPP weekly session, to further emphasize the faith-health relationship from a highly respected member of the church. This study also evaluates possible psychosocial and physiological mediators of the relationship between faith-based programming and outcomes, which has been a consistent call for future research in this area [9, 10]. Lastly, this study uses peer leaders from within the church to ensure cultural relevancy and sustainability.

Faith-based organizations have been involved extensively in health promotion programs in AA communities; however, recent data found that integrating faith components into health promotion (e.g., faith-based) curriculum is not necessarily more effective than delivering standard programming inside a FBO (e.g., faith-placed) [9], although studies have not directly compared this relationship in a randomized design. One study found a beneficial effect of faith-based programming on weight when compared to general health education [38]. The Better Me Within randomized trial allows for comparison of a faith-based DPP program (e.g., faith-enhanced DPP) developed by faith leaders using CBPR approaches as compared to a faith-placed DPP program (secular program held at a church). This comparison provides essential information on whether delivering readily available health promotion programming, such as the DPP, inside a FBO is equally as effective as tailoring health promotion programming to include faith-based principles and activities. This distinction is important as tailoring and delivery of more complex interventions requires greater resources [39]. This is particularly relevant for FBOs in lower income settings with limited capacity to deliver programming.

Conclusion

Overall, by using CBPR approaches from inception to enrollment, the Better Me Within Trial was able to successfully recruit AA FBO and female congregation members. Further, the CBPR approach led to a culturally relevant and novel DDP faith-enhanced adaption. This study will provide essential data to guide enhancements to evidence-based lifestyle programs for high-risk AA women who have demonstrated an attenuated response to evidence-based programs, and a continued increase in chronic disease risk.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a National Institutes of Health grant, P20MD006882-2

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Look ARG, Wing RR. Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: four-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Archives of internal medicine. 2010;170(17):1566–75. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samuel-Hodge CD, Johnson CM, Braxton DF, Lackey M. Effectiveness of Diabetes Prevention Program translations among African Americans. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2014;15(Suppl 4):107–24. doi: 10.1111/obr.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West DS, Elaine Prewitt T, Bursac Z, Felix HC. Weight loss of black, white, and Hispanic men and women in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Obesity. 2008;16(6):1413–20. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311(8):806–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and Trends in Diabetes Among Adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2015;314(10):1021–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, Bowman BA. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. The Lancet. 2014;384(9937):45–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60648-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geronimus AT, Bound J, Keene D, Hicken M. Black-white differences in age trajectories of hypertension prevalence among adult women and men, 1999–2002. Ethnicity & disease. 2007;17(1):40–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancaster KJ, Carter-Edwards L, Grilo S, Shen C, Schoenthaler AM. Obesity interventions in African American faith-based organizations: a systematic review. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2014;15(Suppl 4):159–76. doi: 10.1111/obr.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong A, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Odoms-Young AM, Stolley MR, Fitzgibbon ML. Systematic review of behavioural interventions with culturally adapted strategies to improve diet and weight outcomes in African American women. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2014;15(Suppl 4):62–92. doi: 10.1111/obr.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American journal of public health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S40–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jagosh J, Bush PL, Salsberg J, Macaulay AC, Greenhalgh T, Wong G, Cargo M, Green LW, Herbert CP, Pluye P. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC public health. 2015;15:725. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upchurch DM, Stein J, Greendale GA, Chyu L, Tseng CH, Huang MH, Lewis TT, Kravitz HM, Seeman T. A Longitudinal Investigation of Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Psychosocial Mediators of Allostatic Load in Midlife Women: Findings From the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Psychosomatic medicine. 2015;77(4):402–12. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomfohr LM, Pung MA, Dimsdale JE. Mediators of the relationship between race and allostatic load in African and White Americans, Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. American Psychological Association. 2016;35(4):322–32. doi: 10.1037/hea0000251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Incollingo Rodriguez AC, Epel ES, White ML, Standen EC, Seckl JR, Tomiyama AJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation and cortisol activity in obesity: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:301–18. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasquali R. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sex hormones in chronic stress and obesity: pathophysiological and clinical aspects. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1264:20–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vicennati V, Pasqui F, Cavazza C, Pagotto U, Pasquali R. Stress-related development of obesity and cortisol in women. Obesity. 2009;17(9):1678–83. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeHaven MJ, Ramos-Roman MA, Gimpel N, Carson J, DeLemos J, Pickens S, Simmons C, Powell-Wiley T, Banks-Richard K, Shuval K, Duvahl J, Tong L, Hsieh N, Lee JJ. The GoodNEWS (Genes, Nutrition, Exercise, Wellness, and Spiritual Growth) Trial: a community-based participatory research (CBPR) trial with African-American church congregations for reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors--recruitment, measurement, and randomization. Contemporary clinical trials. 2011;32(5):630–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carson JA, Michalsky L, Latson B, Banks K, Tong L, Gimpel N, Lee JJ, Dehaven MJ. The cardiovascular health of urban African Americans: diet-related results from the Genes, Nutrition, Exercise, Wellness, and Spiritual Growth (GoodNEWS) trial. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112(11):1852–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diabetes Prevention Program Research G. Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Christophi CA, Hoffman HJ, Brenneman AT, Brown-Friday JO, Goldberg R, Venditti E, Nathan DM. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1677–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, Smith SC, Jr, Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT, Jr, Narva AS, Ortiz E. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311(5):507–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carithers TC, Talegawkar SA, Rowser ML, Henry OR, Dubbert PM, Bogle ML, Taylor HA, Jr, Tucker KL. Validity and calibration of food frequency questionnaires used with African-American adults in the Jackson Heart Study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2009;109(7):1184–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subar AF. Developing dietary assessment tools. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104(5):769–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabriel KP, McClain JJ, Lee CD, Swan PD, Alvar BA, Mitros MR, Ainsworth B. Evaluation of physical activity measures used in middle-aged women. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2009;41(7):1403–1412. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31819b2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saunders RP, Evans MH, Joshi P. Developing a process-evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: a how-to guide. Health promotion practice. 2005;6(2):134–47. doi: 10.1177/1524839904273387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson DK, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Resnicow K, Van Horn ML, St George SM, Siceloff ER, Alia KA, McDaniel T, Heatley V, Huffman L, Coulon S, Prinz R. An overview of the Families Improving Together (FIT) for weight loss randomized controlled trial in African American families. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;42:145–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fairchild AJ, MacKinnon DP. A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prevention science : the official journal of the Society for Prevention Research. 2009;10(2):87–99. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0109-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ. Current Directions in Mediation Analysis. Current directions in psychological science. 2009;18(1):16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taljaard M, Donner A, Klar N. Imputation strategies for missing continuous outcomes in cluster randomized trials. Biom J. 2008;50(3):329–45. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200710423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Little RJ. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83(404):1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu T, Gao X, Chen M, van Dam RM. Long-term effectiveness of diet-plus-exercise interventions vs. diet-only interventions for weight loss: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2009;10(3):313–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological bulletin. 1992;112(1):155. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donner A, Klar N. Statistical considerations in the design and analysis of community intervention trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(4):435–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00511-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sattin RW, Williams LB, Dias J, Garvin JT, Marion L, Joshua TV, Kriska A, Kramer MK, Narayan KM. Community Trial of a Faith-Based Lifestyle Intervention to Prevent Diabetes Among African-Americans. Journal of community health. 2016;41(1):87–96. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0071-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glasgow RE, Fisher L, Strycker LA, Hessler D, Toobert DJ, King DK, Jacobs T. Minimal intervention needed for change: definition, use, and value for improving health and health research. Translational behavioral medicine. 2014;4(1):26–33. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0232-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.N. NIH, L. National Heart, B. Institute, N.A.A.f.t.S.o. Obesity. NIH Publication Number DO-4084. 2000. The Practical Guide Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults; pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bosy-Westphal A, Booke C-A, Blöcker T, Kossel E, Goele K, Later W, Hitze B, Heller M, Glüer C-C, Müller MJ. Measurement site for waist circumference affects its accuracy as an index of visceral and abdominal subcutaneous fat in a Caucasian population. The Journal of nutrition. 2010;140(5):954–961. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.118737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Thornton JC, Bari S, Williamson B, Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Horlick M, Kotler D, Laferrere B, Mayer L, Pi-Sunyer FX, Pierson RN. Comparisons of waist circumferences measured at 4 sites. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(2):379–384. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carey M, Markham C, Gaffney P, Boran G, Maher V. Validation of a point of care lipid analyser using a hospital based reference laboratory. Irish J Med Sci. 2006;175(4):30–35. doi: 10.1007/BF03167964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dale RA, Jensen LH, Krantz MJ. Comparison of two point-of-care lipid analyzers for use in global cardiovascular risk assessments. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(5):633–639. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arrendale JR, Cherian SE, Zineh I, Chirico MJ, Taylor JR. Assessment of glycated hemoglobin using A1CNow+™ point-of-care device as compared to central laboratory testing. Journal of diabetes science and technology (Online) 2008;2(5):822. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gabriel KP, McClain JJ, Lee CD, Swan PD, Alvar BA, Mitros MR, Ainsworth BE. Evaluation of Physical Activity Measures Used in Middle-Aged Women. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2009;41(7):1403–1412. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31819b2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crouter SE, Schneider PL, Karabulut M, Bassett DR. Validity of 10 electronic pedometers for measuring steps, distance, and energy cost. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2003;35(8):1455–1460. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078932.61440.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider PL, Crouter SE, Lukajic O, Bassett DR. Accuracy and reliability of 10 pedometers for measuring steps over a 400-m walk. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2003;35(10):1779–1784. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000089342.96098.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Worthman CM, Stallings JF, Hofman LF. Sensitive salivary estradiol assay for monitoring ovarian function. Clin Chem. 1990;36(10):1769–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu Y, Bentley GR, Gann PH, Hodges KR, Chatterton RT. Salivary estradiol and progesterone levels in conception and nonconception cycles in women: evaluation of a new assay for salivary estradiol. Fertil Steril. 1999;71(5):863–8. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gozansky WS, Lynn JS, Laudenslager ML, Kohrt WM. Salivary cortisol determined by enzyme immunoassay is preferable to serum total cortisol for assessment of dynamic hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Clin Endocrinol. 2005;63(3):336–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH. Salivary cortisol in psychobiological research: an overview. Neuropsychobiology. 1989;22(3):150–69. doi: 10.1159/000118611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vining RF, McGinley RA, Maksvytis JJ, Ho KY. Salivary cortisol: a better measure of adrenal cortical function than serum cortisol. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry: An international journal of biochemistry in medicine. 1983;20(6):329–335. doi: 10.1177/000456328302000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Avalos L, Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow N. The Body Appreciation Scale: development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image. 2005;2(3):285–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]